Mechanisms to Support Interventions Involving the Police When Responding to Persons Experiencing a Mental Health Crisis: A Realist Review

Abstract

Mental health crisis interventions involving police originated in the United States. In England and Wales, street triage services (a UK term used to describe urgent mental health and police interventions) were piloted in 2013. These models involve police and mental health services working together to ensure individuals receive the required support. Evaluation findings have shown inconsistent outcomes based on studies predominately limited to single sites. Evaluations to date have lacked theoretical consideration of the contexts and mechanisms triggering outcomes for service users. This review used a realist approach to develop an explanatory understanding of what happens in interventions involving the police responding to individuals experiencing a mental health crisis (underlying mechanisms), the contextual conditions surrounding the implementation of these interventions (context) and the outcomes produced as a result. The review was conducted using a two-stage process. Stage one generated initial programme theories, which informed a systematic literature search (stage two), which further developed, tested theories. From 6461 potentially relevant papers identified in stage two, 19 papers were included. Extracted data were themed, prior to developing narrative and formulating programme theories. In six programme theories, spanning four themes were developed: role legitimacy of police as responders to mental health crises, using technology, complex decision-making and responding to distress. Findings indicate that central to successful interventions involving the police in mental health crisis responses is the requirement of social relationships and joint working between police and mental health services to foster trust. Presented findings contribute to a more detailed understanding of mechanisms within interventions involving the police in mental health crisis responses. By generating evidence-based understandings of the effective components of these support interventions, this research has potential to inform development of future such support at a time of significant policy changes impacting on the role of police as responders to mental health crises.

1. Introduction

An international drive for predominantly community based, rather than institutional care, has necessitated development of mental health services that are able to respond to people’s need for urgent help with their mental health in community settings [1]. Policy, driving the development of community-based crisis services in England and Wales, has followed initiatives internationally [2–6] and was initiated in England from 2000 [7]. The Crisis Care Concordats in England in 2015 [8] and Wales in 2015 [9] set out multiagency agreements for interagency collaboration in the delivery of mental health crisis care and contributed to a proliferation of complex pathways into and through crisis care [10]. These pathways include, for example, accident and emergency departments [11], NHS crisis resolution services [12], emergency telephone lines [13], voluntary sector services [14] and blue light services such as ambulance services [15] and the police [16]. In addition, a number of policy and legal changes have come into effect including moves to more collaborative working, changes to police powers under the Mental Health Act [17], and the ‘Right Care Right Person’ (RCRP) policing initiative, which is currently underway in England [18].

NHS data estimate that there are 250,000 calls to mental health crisis services per month in England [13]. Mental health crises have a complex aetiology related to lifestyle, social circumstances and physical and mental health [19]. Conceptualisation of mental health crises is aligned with individual values and beliefs about health and illness [20–22], informed by factors such as social stigma [23], or previous traumatic experiences [24] and inform if, when, and from whom people seek help [25]. Consequently, people may make their first contact with services in a crisis in planned or unplanned ways and through a variety of community-based routes including mental health services, primary care, urgent care, voluntary sector, the ambulance service or the police [26].

Mental health crisis interventions involving police originated in the United States [27] and Australia [28] to ensure that people experiencing mental distress coming into contact with the police could be identified and provided appropriate support. These international models, including The Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) model in the United States, focus on providing specialist mental health training for police and the development of specialist mental health policing roles [29]. In England and Wales, street triage services were piloted in 2013(30). A key difference between street triage and models such as CIT is the focus on coresponses that enable policing and mental health expertise to be brought together through collaborative working at the scene, rather than sole police responders with specialist training [16, 26]. The key purpose of the street triage model is to improve first responses to people in crisis, where police might previously have been sole first responders resulting too often in application of their powers under Section136 (S136) of the Mental Health Act (England and Wales) or arrest for public order offences [17, 30]. Whilst detention using appropriate legal powers is necessary for a minority of people where risks of harm are imminent, overuse of such powers is contrary to policy advocating least restrictive approaches to mental health care [31]. Equally, failure to provide accessible, co-ordinated first responses to mental health crises can contribute to catastrophic outcomes such as self-harm, suicide, unresolved distress and trauma [32, 33] or greater than necessary use of force [34].

An evaluation of pilot street triage sites in England showed that the configuration of triage in these services varied substantially, from mobile units with nurses and police working together, to call centres where mental health staff assist and advise officers attending incidents via telephone [35]. Furthermore, evaluations of street triage have been limited to single sites [36, 37] and lack theoretical consideration of the contexts and mechanisms triggering optimal (or suboptimal) outcomes. A recent international systematic review aimed to identify models of coresponse police mental health triage and to evaluate the effectiveness of those services [16]. Overall, results indicated that the implementation of coresponder models was associated with a reduction in the use of police powers of detention (S136) and a reduction in detention in police custody [16]. The review noted, however, that one of the key limitations in the current evidence base is the inadequate description of coresponse models and the variation in their operationalisation [16]. To inform service improvement, alongside understanding local context, a better understanding of which components of coresponse models are most effective and most acceptable to service users (or not) is needed.

With more people experiencing mental health crises, and with increased pressures on mental health services to respond with reduced and more targeted input from the police for only those situations where there is a risk to life or a crime has been committed [13, 18], there is a need for research to develop a theoretical understanding of the best way(s) to produce optimal outcomes and experience for people experiencing mental health crises who come into contact with the police. This realist review therefore aimed to develop an explanatory understanding of what happens in interventions involving the police responding to individuals experiencing a mental health crisis (underlying mechanisms), the contextual conditions surrounding the implementation of these interventions (context) and the outcomes produced as a result.

2. Methods

- a.

What are the key mechanisms that underpin models of mental health crisis response involving the police in England and Wales?

- b.

How do different contexts trigger or inhibit these mechanisms?

- c.

How does the link between contexts and mechanisms impact on outcomes of crisis interventions involving the police (including health economic outcomes)?

- d.

What are the service user outcomes of interest and how are these related to the driving mechanisms and contextual factors?

This review used a realist approach to explore how interventions involving the police responding to individuals experiencing a mental health crisis ‘work’, through positively impacting on the individuals experiencing a mental health crisis in England or Wales. The rationale for using this approach is that such interventions are complex, likely to consist of many components, and are contingent on the behaviours and choices of those involved. The specific links between such interventions and their impact are inherently uncertain and emergent [38]. Thus, a realist approach addresses these complexities by focussing on the interrelationships between, and placing emphasis upon, understanding the causal mechanisms within the context dependent nature of interventions. This allows for theory to be developed about ‘why’ interventions work, to better understand how and why differential outcomes occur for who and in which circumstances.

2.1. Realist Methodology

Realist reviews are theory-driven approaches to organising and synthesising data. They provide an explanatory focus through which the notion of generative causation (underlying causal factors) is used to assist with postulating theories about how and why interventions ‘work’, for whom, under what circumstances [39]. In addition to providing explanations as to ‘why’ such relationships come about, propositions about how an intervention is thought to work, under what conditions are developed in the form of programme theories [40].

From a realist perspective, interventions operate through introducing new ideas and/or resources into existing contexts. It is assumed that if the intervention is implemented, a change in outcome(s) will occur [41]. This change is perceived to be operationalised through mechanisms which create change by modifying the capacities, resources, constraints and choices of those involved. This review is therefore, more than a summary of existing literature, but instead provides an ‘explanatory model’. Explanatory models provide a detailed and highly practical understanding of complex interventions which involve the police responding to individuals experiencing a mental health crisis, including identification of how the context surrounding these mechanisms impacts on the observed outcomes.

2.2. The Review Process

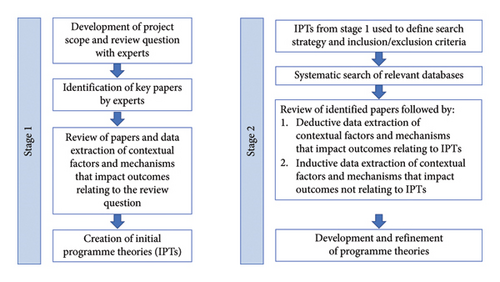

The review was preregistered on PROSPERO, the international prospective register of systematic reviews: CRD42023427107. Based on the principles of realist inquiry and review methodology [42] the review was conducted using a two-stage process (Figure 1). Stage one aimed to generate initial programme theories (IPTs). These theories then informed a more detailed systematic literature search within stage two which sought to further develop, refine and test theories.

2.2.1. Realist Review: Stage 1

The first stage of the review was to create IPTs, in an effort to begin to develop an understanding of what happens in interventions involving the police responding to individuals experiencing a mental health crisis. This began with the development of the project scope and formulation of the review question.

Papers were identified through consultation with clinical and academic experts [43] and from the reference list of a recent realist review of community crisis services [20] and systematic review of Street Triage [16]. Papers were reviewed by the research team and relevant data were extracted focussing on contextual factors and mechanisms that impact outcomes from the interventions, contributing towards inference making [44] to build an understanding of how context and mechanisms interact to produce outcomes. This approach allowed for linkages to be made through the systematic application of retroductive theorising [45], creating a conceptual framework in the form of IPTs. IPTs were presented to the wider stakeholder group, which included representation from academics, senior psychiatrist and a person with lived experience of mental health crisis services for sense checking. The involvement of the stakeholder group added validation of the knowledge produced through the IPTs.

2.2.2. Realist Review: Stage 2

Stage two used the IPTs to inform a systematic focused search of the literature. The purpose of this search was to further expose and unpack the complexities of the contexts and interrelated mechanisms, including their impact upon outcomes, identified through the development of the IPTs in stage one [46] and to provide a more comprehensive explanatory potential of results. Searches were therefore purposive, with search terms reflecting the IPTs.

2.3. Searches

- a.

(“street triag∗” OR “liaison and diversion” OR “speciali? ed mental health response∗” OR co-responder∗ OR “co responder∗” OR “crisis intervention team∗” OR “Section 136”, OR “psychiatric emergency response team∗”)

- b.

(policing OR police AND triag∗ OR “crisis team∗” OR “mental health” OR liaison)

- c.

(“mental health” AND triag∗ OR “crisis team∗” OR paramedic∗ OR ambulance)

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies of any individual experiencing a mental health crisis (as defined in the crisis care concordats of England and Wales [8, 9]) which had police involvement in responding to the crisis were included. Studies of individuals not in a mental health crisis or studies with no involvement from the police were excluded. There were no restrictions on the types of study to be included in line with the Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES) quality standards for realist reviews [42] and the related approach of meta-narrative reviews. All records from the search were imported into Rayyan, an electronic screening platform, with duplicates removed. Each citation was screened for eligibility based on their title and abstract by two independent reviewers (CH, SR, SM, TE, IM, AB, and NC). Reviewers met at each step to resolve discrepancies. Full texts were obtained for all abstracts not excluded.

2.5. Quality Assessment

Inclusion criteria for a realist review is based on ‘…the data′s ability to contribute to theory building and testing.’ [47]. Full texts of documents not excluded at title and abstract screening were assessed and scored in relation to three key areas by two independent reviewers to determine final eligibility (SR and NC). Areas included; the perceived relevance of the data to the IPTs, the conceptual richness and thickness of data presented, and the rigour of methods employed [47]. Taking this approach ensured that all included papers were able to contribute to the testing and refinement of theory building, in line with the RAMESES quality standards for realist reviews [42]. This facilitated the interpretation of concepts from the papers, into constructing explanatory theories alongside interpreting and recontextualising of data into the formulation of ‘best explanations’ [45].

2.6. Data Extraction

A data extraction template was developed to allow for consolidation of data across included documents. The template, based on IPTs already developed in stage one, structured the extraction in order that evidence on what appears to work, for whom, how and in what contexts was documented. Data were extracted by one reviewer (SR) with a 20% sample check carried out by a second reviewer (NC). The extracted data were reviewed by the project team and used to check and refine propositions from the IPTs in the support or refuting of them. Extracted data focused on context, mechanism and outcome configurations, demi-regularities and mid-range theories with relevance, richness and rigour applied for quality assessment [47].

2.7. Data Synthesis

The approach taken to synthesise extracted data was based on the principles of realist evaluation [39]. This included the organisation of extracted data into evidence tables of context, mechanism, outcome; theming of data; linking of the chains of inference within and between themes; development of the narrative; and programme theory formation.

3. Results

3.1. Realist Review: Stage 1

In total, 21 papers were included in stage one, resulting in identification of 17 IPTs (Supporting data file 1) which focused on; implementation of street triage; hours of operation; the use of portable technology; cross-agency data sharing; geographic service boundaries; rural and urban settings; collaborative working; a lack of team working; role conflict, role clarity and resourcing, shared specialist skills, reducing distress, family, friends and carers, stigma and three IPTs related to training.

3.2. Realist Review: Stage 2

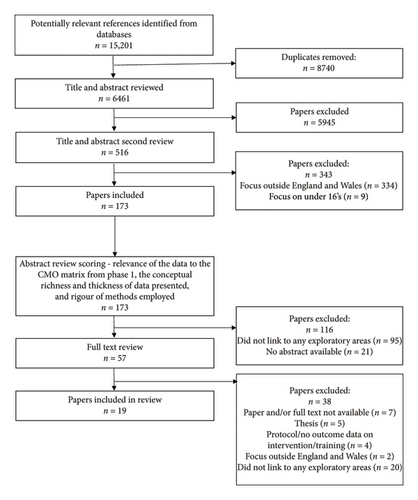

Searching resulted in 6461 unique potentially relevant papers. Of these, 6288 were excluded during title and abstract screening as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. One hundred and seventy-three papers were scored for relevance, conceptual richness and rigour resulting in exclusion of a further 116 papers. The remaining 57 papers were obtained and read in full, and 38 papers were excluded as they were unavailable in full text (n = 7), did not meet inclusion criteria (n = 7), were study protocols and contained no data (n = 4), and 20 papers did not link to any explanatory areas. Six papers included at stage one were also included at stage two [16, 48–52]. A total of 19 records were included in stage two as shown in Figure 2.

3.3. Overview of Included Studies

Included papers reported police involvement in mental health crisis responses from a total of 120 programmes across England and Wales. Nine of the studies reported more than one programme [16, 51–57], and one study reported 41 programmes [49]. Included studies reported a randomised controlled trial [58]; mixed methods [55, 59, 60]; service evaluation [61]; a national survey [49]; six qualitative studies [51, 52, 54, 56, 62, 63] and three commentary papers [48, 64, 65]. Also included were three literature reviews, of which two were systematic reviews [16, 57] and one scoping review [53]. These reviews included a total of five studies also included in this review [51, 52, 55, 61, 63]. The characteristics, relevance, richness and rigour of included documents are shown in Table 1.

| Authors | Date | Title | Paper category | Design | No. of schemes/forces reported on | Included in the development of IPT | No. of explanatory areas paper linked to | ‘Conceptual richness—does the paper demonstrate theoretical and conceptual development that explains how an intervention is expected to work? (5 very high conceptual richness—1 very low conceptual richness) | Conceptual thickness—is sufficient detail provided to establish what is occurring in the intervention as well as in the wider context and to infer whether findings can be transferred to other people, places, situations or environments? (5 very high conceptual thickness—1 very low conceptual thickness) | Rigour—is the method used to generate data that are credible and ‘trustworthy’? (5 very high rigour—1 very low rigour) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scantlebury et al. | 2017 | Effectiveness of a training program for police officers who come into contact with people with mental health problems: A pragmatic randomised controlled trial | Peer reviewed journal | Cluster randomised control trail | 1 | No | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Uddin et al. | 2020 | Simulation training for police and ambulance services to improve mental health practice | Peer reviewed journal | Mixed methods study | 1 | No | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Dyer et al. | 2015 | Mental health street triage | Peer reviewed journal | Evaluation | 1 | No | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Park et al. | 2021 | Models of mental health triage for individuals coming to the attention of the police who May Be experiencing mental health crisis: A scoping review | Peer reviewed journal | Scoping review | 33 (12 England/Wales) | No | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Callender et al. | 2021 | Mental health street triage: Comparing experiences of delivery across three sites | Peer reviewed journal | Qualitative study | 3 | Yes | 9 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Horspool et al. | 2016 | Implementing street triage: a qualitative study of collaboration between police and mental health services | Peer reviewed journal | Qualitative study | 2 | Yes | 9 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Broome et al. | 2022 | Service evaluation of the South Wales police control room mental health triage model: outcomes achieved, lessons learned and next steps | Peer reviewed journal | Evaluation | 1 | Yes | 8 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Wondemaghen et al. | 2021 | Policing mental illness: Police use of Section 136—Perspectives from police and mental-health nurses | Peer reviewed journal | Qualitative study | 5 | No | 6 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Kane et al. | 2018 | Mental health and policing interventions: Implementation and impact | Peer reviewed journal | Mixed methods study | 2 | No | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Kirubarajan et al. | 2018 | Street triage services in England: Service models, national provision and the opinions of police | Peer reviewed journal | National survey | 41 | Yes | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Thomas et al. | 2019 | Understanding the changing Patterns of behaviour leading to increased detentions by the police under section 136 of the mental health Act 1983 | Peer reviewed journal | Mixed methods study | 1 | No | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Genziani et al. | 2020 | Emergency workers’ experiences of the use of Section 136 of the mental health Act 1983: Interpretative phenomenological investigation | Peer reviewed journal | Qualitative study | 1 | No | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Menkes et al. | 2014 | Diagnosing vulnerability and ‘dangerousness’: police use of section 136 in England and Wales | Peer reviewed journal | Qualitative study | 3 | No | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Xanthopoulou et al. | 2022 | Subjective experiences of the first response to mental health crises in the community: a qualitative systematic review | Peer reviewed journal | Systematic review | 79 (22 England/Wales) | No | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| Cummins et al. | 2016 | Policing and street triage | Peer reviewed journal | Commentary | n/a | Yes | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Puntis et al. | 2018 | A systematic review of coresponder models of police mental health ‘street’ triage | Peer reviewed journal | Systematic review | 23 | Yes | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Cole | 2016 | A caring approach for people in crisis | Practice commentary | Commentary | n/a | No | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Cummins et al. | 2023 | Defunding the police: A consideration of the implications for the police role in mental health work | Peer reviewed journal | Commentary | n/a | No | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Lamb et al. | 2019 | ‘It’s not getting them the support they need’: Exploratory research of police officers’ experiences of community mental health | Peer reviewed journal | Qualitative study | 1 | No | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

3.4. Key Mechanisms Underpinning Models of Police Involvement in Mental Health Crises and Development of Programme Theories

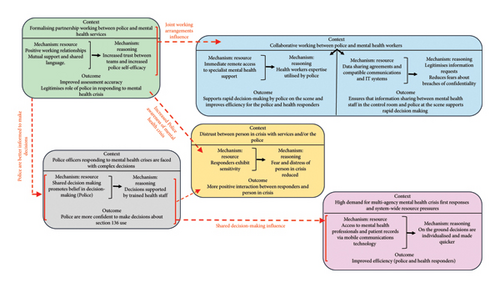

The review resulted in the development of six programme theories, spanning four themes. An overview of the programme theories is illustrated in Figure 3. The themes and associated programme theories are presented below.

3.5. Theme 1: Role Legitimacy of Police as Responders to Mental Health Crises

Many of the included papers referred to police officers lacking training in mental health [16, 51, 52, 54, 56, 58, 59, 61, 63]. Mental health training was consistently described as work based, rather than included in professional programmes in policing. A lack of clarity on the specific training needs [52, 56, 59, 63] or competencies [63] required of police responding to mental health crises was identified.

Mental health training that was delivered in partnership between police and health staff was advocated [52, 63]. In particular, training delivered within the local setting where the staff were working, enabled local contextual factors to influence the content of training [58] and also fostered positive working relationships between staff across different agencies [16, 51, 54, 63]. Some constabularies mandated training delivered by local mental health NHS staff for all police officers [58]. Others prioritised training for police and health staff working in control rooms and for police officers routinely responding to mental health calls [55].

Face-to-face training that included practical and simulated learning was advocated particularly for police officers with limited direct experience responding to mental health crises [55, 56]. Involvement of people with lived experience and expert health staff in training delivery [52, 58] highlighted the importance of attitudes and interpersonal skills [66]. Police officers asked for more training in interpersonal skills focused on responding to someone who is very agitated [56] including skills to convey empathy and compassion [63].

The intervention resources provided by training included identification of vulnerable populations more likely to experience mental health crises [54, 58], training in risk assessment and management, mental health topics [58] and mental health law with a specific focus on emergency sections of the Mental Health Act [56]. Important elements of training for police included information about locally relevant multiagency crisis care services, processes involved in record keeping and referral and resource availability [58].

PT 1: Formalising partnership working between the police and mental health teams through joint training delivery (C), assists in the formation of positive working relationships between police officers and mental health staff whereby mutual support and a shared language is developed (M, resource) which improves assessment accuracy and the coordination of the first response and its follow-up (O) due to increased trust between the teams and increased self-efficacy of police officers when responding to mental health crisis (M, reasoning) which ultimately assists in legitimising the role of police officers in responding to mental health crisis (O).

3.6. Theme 2: Using Technology

The resources required to ensure that rapid multiagency responses can meet population demand and overcome organisational and geographic barriers were identified [49–51, 53]. Limitations in the data included missing detail concerning the circumstances in which face-to-face (ride-along) or control room (telehealth) models were most likely to produce optimal outcomes [16, 49, 64].

The inclusion of telehealth as part of coresponse models emphasised the improved ability to provide 24/7 access [49, 50, 52] that included direct telephone access to specialist mental health staff [50, 51]. Telehealth communication between police at the scene and mental health staff via the control room facilitated greater efficiency, by removing the need for health staff to travel to the scene of the crisis without compromising police access to immediate specialist advice [49–51]. Importantly, the telehealth response was individualised because health staff had direct and immediate access to the health record that optimised efficiency of decision-making by using available resources including safety plans, current medications and care plans [50]. Barriers to accessibility of crisis responses in both urban and rural areas could also be overcome using telehealth [50, 51, 53] as well as providing a means to operate across organisational boundaries [50].

PT 2.1: When there is a high demand for multi-agency mental health crisis first responses and there are system-wide resource pressures impacting on being able to meet this demand (C), being able to access an emergency control room, available 24/7 that has direct access to mental health professionals and health records via mobile communications technology (M, resource), on the ground decisions are able to be more individualised to the person (M, reasoning) in crisis and made quicker, thus improving efficiency for the police and health responders (O).

PT 2.2: By having immediate remote access to specialist mental health support (M, resource) in a context of collaborative working between police and mental health workers (C), police working with the person in crisis are able to utilise health workers expertise to act as intermediaries between agencies across organisational and geographic boundaries (M, reasoning) which supports rapid decision making by police on the scene and improves efficiency for the police and health responders (O).

PT 2.3: Collaborative development (C) of data sharing agreements and compatible communications and IT systems to meet local cross-agency requirements (M, resource), legitimises requests from first responders for information about individuals and reduces fears about breaches of confidentiality whilst also safeguarding personal data (M, reasoning). Having these agreements in place ensures that information sharing between mental health staff in the control room and police at the scene supports rapid decision making thus improving efficiency for the police and health responders (O).

3.7. Theme 3: Complex Decision-Making

Decisions by police officers to use S136 are complex, influenced by an interplay between legal, organisational and institutional factors, the social context and the individual experiencing a crisis [56], and yet were often based on limited mental health knowledge or experience [57]. Policing decisions at the scene of a mental health crisis are also complicated by conflicting policy priorities between ensuring public safety and also reducing the use of restrictive interventions such as Section 136 of the Mental health Act [17, 56].

Police apply Section 136 at the scene of a mental health crisis, when they believe it to be the safest response, and have concluded that at that time, they have no alternative [54, 57]. Decisions to apply S136 can be the result of a lack of available and timely mental health follow-up [56] leading to an unnecessarily extended time at the scene for police and ambulance responders [50, 62] and a lack of specialist mental health support for the individual, noted as a particular issue in rural communities [56].

PT 3: Police officers responding to mental health crises are faced with complex decisions about a course of action to maintain public safety whilst also limiting their use of Section 136 of the Mental Health Act (C). Shared decision making across police and mental health agencies promotes police officers’ belief in their decision-making (M, resource). As decisions are supported by trained health staff (M, reasoning) and thus police are more confident to make decisions about Section 136 use (O).

3.8. Theme 4: Responding to Distress

People experiencing mental health crises can be highly distressed, fearful and lack trust in mental health services and the police due to previous negative or traumatic experiences [50, 57] and stigma [61]. When police officers are sensitive about how they may be perceived by the person in crisis [62] or by family, or companions [50] and engage with the person in nonthreatening ways, fear is reduced and trust developed because the person in crisis believes that the first responders wanted to help and that they are nonjudgemental [50, 57, 62]. This is achieved by assigning one police officer to communicate and lead the response (rather than a number of uniformed staff crowding the situation), by taking their hat off, not standing with their arms crossed and turning down the volume on their radio [57, 62]. Using communication skills including listening, altering voice tone and seeking permission to talk, touch or examine the person reduces distress and fear [50, 57, 62].

At the scene of a crisis involving the police, family or companions may be present and may have made the call to emergency services [50, 57]. Having made the call, they may experience guilt and benefit from reassurance and support at the scene [50, 57, 62]. Maintaining family/companion involvement may, for some people experiencing a crisis, provide additional reassurance from the presence of someone familiar [57].

PT 4: In a context of distrust between the person experiencing a mental health crisis with mental health services and/or the police (C), if responders exhibit sensitivity as to how they may be perceived, through acts such as taking off their hat or seeking permission to talk (M, resource), fear and distress of the person in a mental health crisis can be reduced (M, reasoning) which fosters a more positive interaction between responders and person in crisis and their companions, in addition to reducing the need for restrictive interventions (O).

4. Discussion

The police has a long history of supporting people with mental health issues in community settings through a range of different models internationally [27, 28, 67, 68]. The introduction of street triage services in England and Wales in 2013 saw the development of several different street triage service configurations including ride along and telehealth approaches [16]. Limitations within health and social care systems have meant that lived experience accounts describe access to rapid, appropriate and compassionate responses to people experiencing psychiatric distress as lacking [69]. While the new policing strategy ‘RCRP’ [18] has realigned policing to its core functions in England, there will continue to be street triage services and situations requiring police responders. It is therefore timely and vitally important to better understand how the resources provided of by street triage services and police responses to mental health crises more generally are most effective.

This review has therefore examined relevant literature to develop a detailed explanatory understanding of what happens in interventions involving the police, within the geographic context of England and Wales, when responding to individuals experiencing a mental health crisis. Importantly, the programme theories developed and tested within the synthesis have allowed for identification and investigation of core mechanisms viewed to influence the implementation of these interventions. In discussing context and mechanism components, alongside the associated outcomes they produce, the role legitimacy of police as responders to mental health crises, the use of technology, influence of complex decision-making, and response to distress are identified as central to effective support interventions involving the police when responding to persons experiencing a mental health crisis.

Much of the context of the findings presented in this review should be considered in relation to the apparent lack of clarity about the role of police which was evident, to some degree throughout all the documents included. The police routinely encounters people experiencing mental health issues but experience conflicts regarding their role, responsibility and ability to provide crisis responses [63]. Many of the included studies identified that this is because police officers in England and Wales specifically are neither mental health experts nor health care providers and many believe that by providing mental health crisis responses, policing is being pulled away from its central purpose [51, 54–56, 60, 63]. A key difference between the street triage model and other models internationally is the specialist mental health training and role specifications for police officers [29, 35]. An unintended consequence of implementing a street triage coresponder model in England and Wales is a lack of clarity about the mental health training needs of police officers delivering street triage, police officers in general and a less clear delineation of the role of police officers as mental health responders.

Central to the programme theories developed through this review is the concept of joint working between the police and mental health services. This joint working can be viewed in terms of social capital theory, whereby the social capital built between the police and mental health services is seen as a ‘resource’ which those involved can benefit from, by virtue of their membership in the social network [70]. Social capital in this sense can be broadly defined as a ‘collective asset’ consisting of ‘…shared norms, values, beliefs, trust, networks, social relations, and institutions that facilitate cooperation and collective action for mutual benefits’ [71] (p.480).

Social relationships between teams established as a result of the joint training and the working context are seen to yield productive benefits for both police and mental health services, namely, better working relationships, between teams [16, 51, 54, 63]. In increasing this social capital, these joint working arrangements are able to positively influence practical working arrangements such as technological developments, in terms of access to relevant health data for example. Evaluations of international coresponse models have also identified the importance of collaborative governance of service delivery fostering contact between agencies at all levels of the organisations involved [20, 72].

Recent strategic changes to policing strategy in England [18] perhaps reflect a lack of ‘mutual benefit’ from the predominant models of police responses to mental health crises in England and Wales over the previous decade. Police commentators in England have for some time believed that they are gap filling for health services [73] potentially leave significant budgetary and resource gaps for other health-based providers of mental health crisis services [74]. The impacts of these policy changes on interagency crisis responses are presently unknown as exemplified by a systematic review with null findings [75]. While the social networks formed through facilitated joint training and working of the police and mental health services also ‘facilitate co-operation’ within a theory of social capital [71], an unintended consequence of the rapid implementation of the Right Care Right Person policing strategy [18] may compromise the sense of ‘co-operation’ that the crisis care concordats were initiated to overcome [8, 9].

The findings here suggest that police roles within street triage models are less well-defined leaving police struggling for role legitimacy as first responders to mental health crises. This is important as frustration and friction between different agencies [60, 62, 63] can disrupt working relationships when responders engage in disputes about responsibility [50, 62]. Disputes such as these create distrust between agencies [50] and act in opposition to the mechanism of trust that our findings identify as critical to interagency working and providing safe and meaningful first responses to people experiencing a crisis and their family or companions. An outcome of distrust is prolonged distress for people in crisis and police officers on the ground losing faith in advice provided by health agencies. This can lead to an unintended consequence of police resorting to using S136 as a means to assure safety [50, 56, 62].

Improved awareness of mental health crisis facilitated through training and increased social relationships between police and mental health teams is viewed to impact on responders’ ability to exhibit sensitivity when interacting with people in mental health crisis. By understanding and being sensitive to the individual in crisis and their situation, responders are able to promote a more positive and effective interaction with the person in crisis [50, 57, 62]. This increased sensitivity also goes some way to addressing wider issues of distrust of the police [65]. However, it should be noted that Scantlebury et al. [58] debate the link between mental health training for police and impact on outcomes.

To date, outcomes and effectiveness of interventions involving the police responses to mental health crisis are often linked to the use of Section 136. However, as described in relation to complex decision-making, the decisions by police officers to use S136 are not straight forward and are further compounded by conflicting policy priorities between public safety and reducing the use of S136 [55]. Whilst measurement of rates of Section 136 will continue to be an important outcome measure, there is a pressing need to capture outcomes related to the individual and their mental health, and service outcomes relating to the wider interagency crisis system as previously identified in reviews of crisis services [20]. In the context of rapidly changing policing policy, there are significant gaps in our understanding of the optimal roles of police, the impact on the wider interagency crisis response system, decision-making, and the lived experiences of people seeking crisis support.

4.1. Study Strengths and Limitations

This review brings together data from a number of different street triage service configurations. In doing so, we have identified key mechanisms influencing effective service delivery. Through this approach, we have been able to identify outcomes which go beyond whether or not such services ‘work’ but identify key outcomes which impact on the wider field of police response to persons in mental health crisis. A core strength of this review was the number of programmes covered by the included papers, and as such contributing towards our analysis.

A key limitation of the review was the lack of engagement with wider stakeholders throughout the process in order to better situate and contextualise the research. Whilst a stakeholder group was engaged to discuss emerging findings from stage one, this could have been further developed. The decision to take a two-staged approach to the review may have resulted in the exclusion of literature which would have been included in a one-stage approach. Whilst this is acknowledged, the two-staged approach was deemed relevant due to the size and scope of available literature on the topic. In addition, the review is focused on English and Welsh based models. This decision was taken in order that findings would represent key contextual considerations within this geography and in recognition of fundamental differences in the design of international models of police involvement. Further research identifying how these models compare with international models would further the explanatory potential of findings.

5. Conclusion

Programme theories developed and tested within this study focused on explaining what it is within support interventions involving the police when responding to persons in mental health crisis work, for whom, in what circumstances and why. This realist review has explored the contexts, and mechanisms triggered as a result of these support interventions involving the police on the outcomes for both individuals experiencing a mental health crisis and the services connecting to responding to such incidents.

Our analysis indicates that central to successful support interventions involving the police when responding to persons in mental health crisis is the requirement of social relationships and joint working between police and mental health services to foster trust. Although this joint working may take a number of different formats, the central component is that roles of both the police and mental health service should be defined. This in turn supports information sharing, used to facilitate better involvement of support staff (police and mental health) and their ability to use this information to overcome distrust related to previous poor experiences and social stigma enabling improved decision-making and engagement with the person experiencing a crisis.

Overall, these findings have contributed to a more detailed understanding of the core mechanisms within support interventions involving the police when responding to persons in mental health crisis (detailed within the programme theories). Importantly, through generating evidence-based understandings of the effective components of support interventions involving the police when responding to persons in mental health crisis, this research has the potential to inform the development of future such support interventions at a time of significant policy and legal changes within the criminal justice system. Further study looking at mental health crisis pathways would be of benefit to future considerations of how to structure and implement support interventions involving the police when responding to persons in mental health crisis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work was funded by NHS Research Capacity Funding (RCF).

Supporting Information

Supporting data file 1 contains the IPTs developed following first search and data extraction. These were then used to develop the iterative search strategy and structure subsequent data extraction.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.