Understanding Colorectal Cancer Screening Attendance: A Comprehensive Theory of Planned Behaviour Model

Abstract

Population-based colorectal cancer screening programs decrease mortality, but the participation rates are still unsatisfactory. Drawing from relevant psychosocial literature, this study aims to test a widely integrated theory of planned behaviour model applied to colorectal cancer screening attendance. The model considered, at the same time, additional proximal predictors (anticipated regret and self-identity) and distal (via attitude) predictors (trust in institutions and perceived risk in their affective and cognitive facets) of intention. On top, to bridge the intention–behaviour gap, the role of two additional mediators (action and coping planning) was explored. In May-June 2022, 435 adults residing in Campania (Italy) joined a survey assessing variables of interest. Structural equation model results showed that both action and coping planning, which were predicted by intention, significantly predicted attendance. Intention was predicted by attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, anticipated regret and self-identity. Attitude was predicted by trust in institutions and affective perceived risk. A parallel mediation analysis confirmed the role of both action and coping planning as full mediators in the intention–behaviour relation. The proposed comprehensive model can inform future interventions and orienteer the improvement of healthcare access processes.

1. Introduction

According to the most recent data, globally one out of five people will develop cancer during their lifetime and, among these diagnoses, colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide [1], including in Italy [2]. Thus, the WHO promotes the diffusion of population-based screening programs, which are large-scale public health interventions aiming to obtain an early diagnosis for individuals who could be at risk of developing the disease despite showing no symptoms. In particular, not only CRC screening (CRCS) leads to early detection of existing CRC, but it can also find precancerous polyps [3].

In accordance with the European guidelines [4], Italian public healthcare offers men and women aged 50–74 a free CRCS test once every 2 years. Nevertheless, the participation rates are disappointingly low [2], with sizeable regional differences, as the Southern regions have significantly lower rates than Center-North (i.e., 19% vs. 60%; [5]). Among the worst cases, only 23% of the target population in the Campania region participated in the program during the last two years in 2020 [6].

As CRCS programs can provide enormous benefits for public health [4], it is necessary to work on increasing these rates, especially where access is lower, like in Campania. With this aim, by adopting a psychosocial perspective, research must focus on identifying the impact of individual-level factors associated with CRCS attendance to offer scientifically based insight into the best promotion strategies.

2. Literature Review

CRCS attendance has been investigated by employing various theoretical models [7]. Among the most-referred ones, the theory of planned behaviour (TPB; [8]) offers valuable insights [9–11]. The TPB suggests that individuals’ intention to act is a crucial predictor of behaviour, influenced by three belief-based factors: attitude, subjective norms (SN) and perceived behavioural control (PBC). Attitude refers to the positive or negative evaluation of the behaviour, SN reflect the influence of others’ expectations, and PBC encompasses individuals’ assessment of their capacities and faculties to engage in the targeted behaviour, considering both its evaluation as easy or difficult and the beliefs about the adequateness of personal resources. PBC is supposed to predict behaviour both directly and, together with attitudes and SN, indirectly via intention.

The classical TPB model efficiently explains many behaviours (e.g., [12]). Thus, research has investigated whether additional variables can further expand its predictive value (see [13]). In this study, we will summarise relevant literature that introduces additional variables within the TPB model, categorised as (i) additional predictors of intention, (ii) additional predictors of attitude and (iii) variables bridging the intention–behaviour gap.

2.1. Additional Predictors of Intention

Many studies have explored additional variables predicting intention within the TPB model. Sandberg and Conner’s review [14] found that integrating the affective component of anticipated regret (AR) significantly increases the variance explained in intention and behaviour. AR refers to the negative feeling experienced when considering the possibility of not achieving the expected behaviour. This addition helps to overcome TPB’s limitation of assuming individuals are entirely rational in decision-making processes [15]. On the contrary, health decisions are actually impacted by affective-based elements [16, 17], and anticipated emotions are even more associated with both intention and health behaviour than anticipatory emotions (namely, direct reactions to health consequence-related uncertainties experienced in the present; [18]). Coherently, AR has been found to play a pivotal role in predicting intention and behaviour in various health domains, including vaccinations [19, 20], food and water consumption [21, 22] and even cancer screening participation [23, 24]. Notably, in the context of cervical cancer, Sandberg and Conner [24] found a mere measurement effect of AR on screening behaviour, as participants who completed a questionnaire comprising TPB and AR measures showed higher attendance rates compared to those who were asked only about TPB variables, with this effect moderated by intention (with significant differences found only for individuals with higher intention). On the other hand, Hunkin, Turnbull and Zajac [25] showed that measuring AR before intention unexpectedly resulted in a lower intention to participate in CRCS compared to measuring it after intention, highlighting the importance of a mindful approach to its measurement.

Adding self-identity (SI) to TPB variables significantly enhances the predictive power of the model [26, 27]. SI is a motivational component that reflects a prominent aspect of an individual’s self-perception [28]. Drawing from identity theory [29], which posits that the self is constructed based on a person’s various roles in social settings, SI is seen as an antecedent of intention. As individuals internalise role-appropriate behaviours and identify with specific roles, the salience of these aspects of identity becomes closely linked to their intention to perform corresponding behaviours since role-congruent acting is a way to confirm their status as role members [30]. Numerous studies have demonstrated the predictive strength of SI beyond the effects of TPB components. For instance, Rise, Sheeran and Hukkelberg [31] highlighted that SI accounted for an additional 6% of the variance in intention, even after controlling for TPB variables, confirming it as a useful independent predictor of intention. While SI has been extensively examined in the context of healthy eating behaviours (e.g., SI as a healthy eater; [22]), its application in preventive behaviours has yielded mixed results. Notably, Booth et al. [32] found that SI explained an additional 22% of the variance in intentions to test for chlamydia, establishing it as the strongest predictor in their study. In this study, items measuring SI assessed specifically the relevance of undergoing this particular test. Conversely, a study on breast self-examination [33] did not find SI as a person engaged in health-promoting behaviours to be predictive of intention or behaviour. The authors speculated that their study’s generic definition of SI may not have been sufficiently meaningful to impact the specific behaviour of breast examination. Thus, the current study aims to adopt an intermediate approach, examining participants’ SI as individuals engaged in preventive behaviours as an additional predictor of CRCS intention.

2.2. Predictors of Attitude

Beyond the additional direct antecedents of intentions, many studies have integrated distal predictors to TPB [34, 35]. These additions offer advantages as they are sources of information for developing personal beliefs regarding the future adoption of the target behaviour [36].

Trust can be a crucial issue regarding individuals’ adoption of preventive behaviour sponsored by public campaigns, like the CRCS program in Italy. In particular, trust in institutions (TI) reflects people’s perception of institutions’ capability to fulfil their responsibilities and prioritise public health [37]. Several studies have integrated trust within the TPB, considering it a distal predictor of intention via attitude [38, 39]. Concerning preventive behaviour, TI has been studied for vaccine uptake [20, 40], but limited efforts have been made regarding CRCS attendance. Two studies have specifically and empirically explored the role of TI concerning an informed choice to participate in CRCS programs [41, 42], but only employing qualitative methods. Given the reliance on healthcare institutions for information and decision-making, this study aims to examine the role of TI as a distal predictor of intention through attitude.

Research employing the TPB has demonstrated that risk perception significantly influences intention through attitude (e.g., [22]). The cognitive facet of perceived risk reflects the assessment of personal vulnerability to a specific threat [43], while the affective component is commonly referred to as worry, reflecting the emotional response to the perceived threat [44]. Both affective and cognitive risk perception are key antecedents of health behaviours, including CRCS attendance [45]. Previous studies adopting the health belief model (HBM; [46]) as a theoretical framework have mainly recognised the cognitive aspects of risk perception (considering perceived susceptibility to the specific threat and perceived severity of the considered disease) as direct predictors of behaviour [10], neglecting the affective facet. In contrast, drawing on the existing literature that integrates both cognitive and affective risk perception as distal predictors of intention through attitude [20, 47], the current study aims to examine the relevance of both facets for CRCS attendance.

2.3. Bridging the Intention–Behaviour Gap

Health behaviour literature has consistently shown a significant gap between intention and behaviour, as intentions often do not translate into actual actions [48–50]. To identify its source, researchers have examined two levels of these variables: intention to act vs no intention, and performed behaviour vs not performed behaviour. Individuals who fall into a specific profile within this matrix—those who intend to act but fail to perform the behaviour—are primarily responsible for the gap [51, 52].

To bridge this gap, some studies have considered including two self-regulation variables: action planning (AP) and coping planning (CP; [52]). AP involves linking goal-directed behaviours to specific environmental cues by determining when, where and how to perform a behaviour. CP involves anticipating barriers that may hinder the implementation of action plans and developing strategies to overcome them [53].

In a recent study by Le Bonniec et al. [54] about CRCS, individuals with higher intention reported higher levels of SN, PBC and CP than those with lower intention, regardless of their actual behaviour. In addition, when considering behaviour, the study revealed that highly intentioned individuals who successfully performed the behaviour reported significantly higher CP levels than those with high intention that did not perform the behaviour. Conversely, no differences were found for AP.

In this study, we aim to further investigate the roles of AP and CP as mediators in the intention–behaviour gap concerning CRCS attendance.

2.4. The Present Study

According to the literature presented above, the present study aims to test an integrated TPB model applied to CRCS attendance to understand the psychological determinants of such behaviour in South Italy, characterised by low rates. This study was designed and implemented as part of a more comprehensive action-research project named MIRIADE (An innovative model of research-intervention for the identification of adherence profiles to cancer screening), which was founded by the Regional Prevention Plan (PRP Campania 2020–2025 Ministry of Health, Italy) with the main goal of improving cancer screening participation rates within the Italian region of Campania by employing evidence-based psychological actions.

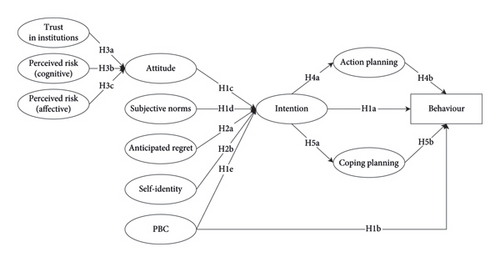

The hypothesised model is shown in Figure 1. We expect to confirm the classical TPB theoretical framework, according to which behaviour is positively and directly predicted by intention (H1a) and PBC (H1b). In turn, intention is positively predicted by attitude (H1c), SN (H1b) and PBC (H1c). Moreover, we expect to confirm the positive predictive role of the considered additional predictors of intention, namely, AR (H2a) and SI (H2b). Furthermore, we also hypothesise the positive role of considered predictors of attitude, which are TI (H3a), and both cognitive (H3b) and affective (H3c) facets of perceived risk. In addition, we expect to confirm the role of the considered self-regulation variables within the intention–behaviour relationship, so we hypothesise that intention will positively predict action (H4a) and CP (H5a) and that both AP (H4b) and CP (H5b) will positively predict behaviour. Lastly, to explore the mediating role of these variables and understand the mechanisms through which they can help bridge the gap, we will explore whether such a relationship is mediated by AP and CP (RQ1), performing a parallel mediation analysis.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Procedure and Participants

The current study was implemented following ethical approval by the Ethical Committee of Psychological Research of the Department of Humanities of the University of Naples Federico II (n. 17/2022). Participants were recruited both online and offline through informal channels, according to a nonprobabilistic snowball sampling technique. Some university students attending courses in social psychology were involved in data collection and were provided with the questionnaire link to spread within their contacts pertaining to the population targeted in the study. All participants gave informed consent for joining the research and knew the survey was anonymous. Data analysed in the present paper are part of a larger dataset and were collected between May and June 2022. Inclusion criteria for participating in the study were (i) being over 50 years old, (ii) not having received a diagnosis of cancer during the last 5 years and (iii) residing in Campania, Italy.

Using an effect size (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation, RMSEA) = 0.5 which denotes a satisfactory fit [55], alpha = 0.05, power = 0.95, df = 630, an a priori power analysis for structural equation models (SEMs) with semPower R package [56] indicated a required sample size of at least 61 units.

Altogether, 435 participants aged 50–73 (M = 59.09; SD = 6.85; 54.3% females) filled out an online self-reported questionnaire assessing the variables of interest. Participants’ sociodemographic characteristics are displayed in Table 1.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Level of education | ||

| Primary education | 35 | 8.0 |

| Secondary education | 284 | 65.4 |

| University degree | 98 | 22.5 |

| Post-university | 18 | 4.1 |

| Employment | ||

| Unemployed | 12 | 2.8 |

| Homemaker | 85 | 19.5 |

| Worker employee | 170 | 39.1 |

| Self-employed worker | 75 | 17.2 |

| Retired | 93 | 21.4 |

| Marital status | ||

| Unmarried single | 31 | 7.1 |

| In a romantic relationship | 23 | 5.3 |

| Married | 314 | 72.2 |

| Divorced | 40 | 9.2 |

| Widow/widower | 27 | 6.2 |

| Religion | ||

| Not practising catholic | 215 | 49.4 |

| Practising catholic | 148 | 34.0 |

| Atheist | 63 | 14.5 |

| Other | 9 | 2.1 |

| Political orientation | ||

| Apolitical | 173 | 39.8 |

| Left-wing | 129 | 29.7 |

| Center | 67 | 15.4 |

| Right-wing | 53 | 12.1 |

| Not specified | 13 | 3 |

3.2. Measures

An online self-report questionnaire was developed according to the study’s aims and implemented on the Google Forms platform. It consisted of various sections containing items and scales to assess psychosocial variables of interest, some questions formulated ad hoc and a section about participants’ personal information. The following paragraphs describe different measures in detail.

3.2.1. Background Knowledge and Experiences With Cancer

The first section of the questionnaire contained some items aimed at measuring nonpsychological variables that could help understand participants’ backgrounds and knowledge about CRC and related screening. Such variables were also added to the model to control for respondents’ characteristics that could influence the examined relationships [57]. Therefore, respondents were asked about their background knowledge of the existence of public cancer screening programs in the Campania region. Then, they were asked whether they had a family history of cancer and if someone had ever had CRC among their friends or family.

3.2.2. TPB Variables

Items for each measure were formulated and adapted following Ajzen’s guidelines [58] for assessing components of the TPB.

Participants were reminded about the suggested frequency of CRCS (once every 2 years from the age of 50), and then they had to report their CRCS attendance on a Likert scale (from 0 = Never to 3 = Regularly).

Intention to participate in CRCS was evaluated by three items using a Likert scale ranging from 1 = Completely disagree to 5 = Completely agree (e.g., ‘I intend to undergo colorectal cancer screening’). Cronbach’s α = 0.91.

Respondents’ attitude towards CRCS was assessed through three items on a semantic differential scale ranging from 1 to 5 (i.e., ‘Undergoing colorectal cancer screening is useless–useful; bad–good; harmful–beneficial’; adapted from [14]). Cronbach’s α = 0.82.

SN were measured by three items on a Likert scale ranging from 1 = Completely disagree to 5 = Completely agree (e.g., ‘Most of the people who are important to me think I should undergo colorectal cancer screening’). Cronbach’s α = 0.95.

PBC was evaluated by four items using a Likert scale ranging from 1 = Completely disagree to 5 = Completely agree (e.g., ‘I have control over my participation in colorectal cancer screening’). Cronbach’s α = 0.84.

3.2.3. Additional Predictors of Intention

AR was evaluated by three items on a Likert scale ranging from 1 = Completely disagree to 5 = Completely agree (e.g., ‘If I did not undergo colorectal cancer screening, I would regret it’; [22]). Cronbach’s α = 0.88.

Participants’ SI as a person engaged in preventive behaviours was assessed by four items on a Likert scale from 1 = Completely disagree to 5 = Completely agree (e.g., ‘I think of myself as someone who is interested in prevention’; [22]). Cronbach’s α = 0.90.

3.2.4. Predictors of Attitude

TI was evaluated by three items using a Likert scale ranging from 1 = Completely disagree to 5 = Completely agree (e.g., ‘If the government offers a colorectal cancer screening program, I assume it is safe’; adapted from [19]). Cronbach’s α = 0.82.

Risk perception was evaluated by seven items adapted from Yıldırım and Güler [59]. Three items measured the cognitive facet of risk, asking participants to report the probability they associate with getting ill using a Likert scale ranging from 1 = Negligible to 5 = Very large (e.g., ‘What is the probability that you will get colorectal cancer?’; α = 0.87). Four items assessed the affective facet of risk asking participants their level of worry about getting ill on a Likert scale ranging from 1 = Not worried at all to 5 = Very much worried (e.g., ‘How worried are you about the possibility of getting colorectal cancer?’; Cronbach’s α = 0.86).

3.2.5. Action Planning and Coping Planning

Participants’ AP was evaluated by two items using a Likert scale ranging from 1 = Completely disagree to 5 = Completely agree (e.g., ‘I have already planned when I will have my next screening for colorectal cancer’; [54]). Cronbach’s α = 0.94.

CP was evaluated by three items using a Likert scale ranging from 1 = Completely disagree to 5 = Completely agree (e.g., ‘For my next colorectal cancer screening, I know how to get organised if I am out of time’; [54]). Cronbach’s α = 0.88.

3.2.6. Demographic Profile

At the end of the questionnaire, participants were asked to provide their age, sex, marital status, employment status, level of studies, political orientation and religion.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

The R statistical software was used for statistical analyses. We had no missing values, as the answer to each item in the questionnaire was mandatory to keep on the completion. For each scale, internal consistency was verified by computing Cronbach’s alpha, and scoring was assessed considering the average of single items’ scores. Descriptive statistics were calculated for each variable. Pearson’s correlations were calculated to measure the strength of the association among the pairs of variables. Moreover, the lavaan package [60] was used to test the hypothesised model (H1-5) with a full SEM [61] based on maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors and a Satorra-Bentler scaled test statistic. Effects of the considered predictors on the main dependent variables (intention to participate in CRCS and CRCS behaviour) were estimated by controlling for those nonpsychological variables that, according to preliminary analysis, showed a significant impact on intention (past vicarious experience with CRC, t = −2.97, df = 433, p = 0.003; professing Catholic religion, t = −2.66, df = 110.51, p = 0.009) and behaviour (past vicarious experience with CRC, t = −4.16, df = 433, p < 0.001; previous knowledge about free public CRCS programs, t = −3.34, df = 433, p < 0.001).

To evaluate to what extent observed data supported the hypothesised model, several fit indices were considered: Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). According to the most referred criteria [55], an adequate fit is defined by CFI and TLI ≥ 0.95, RMSEA ≤ 0.06 and SRMR ≤ 0.08.

Finally, to address our research question about the variables bridging the intention–behaviour gap (RQ1), a parallel mediation analysis was performed using the Monte Carlo method [62] to test the mediating effects of AP and CP in the relationship between intention and behaviour. Each mediating effect was estimated by running 20,000 repetitions to get a 95% confidence interval. To consider indirect effects as statistically significant, the confidence intervals (CIs) had not to include zero.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Regarding nonpsychological variables, 47.8% of the respondents stated they knew about the free CRCS program active in the Campania region. Besides, participants were equally distributed among those with (47.6%) or without (47.6%) a family history of cancer, with a small part unsure about it (4.8%). A percentage of 35.4% stated they had previous experience particularly with CRC among familiars or friends.

Descriptive analyses and Pearson’s correlations among variables are displayed in Table 2.

| M (SD) | Range | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Behaviour | 0.65 (0.87) | 0–3 | — | ||||||||||||

| 2. Intention | 3.21 (1.13) | 1–5 | 0.28∗∗ | — | |||||||||||

| 3. Attitude | 4.37 (0.83) | 1–5 | 0.08 | 0.32∗∗ | — | ||||||||||

| 4. Subjective norm | 3.11 (1.09) | 1–5 | 0.29∗∗ | 0.52∗∗ | 0.28∗∗ | — | |||||||||

| 5. PBC | 3.67 (0.87) | 1–5 | 0.14∗∗ | 0.46∗∗ | 0.26∗∗ | 0.38∗∗ | — | ||||||||

| 6. Action planning | 2.28 (1.14) | 1–5 | 0.40∗∗ | 0.47∗∗ | 0.11∗∗ | 0.34∗∗ | 0.23∗∗ | — | |||||||

| 7. Coping planning | 2.97 (1.10) | 1–5 | 0.37∗∗ | 0.53∗∗ | 0.20∗∗ | 0.38∗∗ | 0.45∗∗ | 0.57∗∗ | — | ||||||

| 8. Anticipated regret | 3.05 (1.05) | 1–5 | 0.31∗∗ | 0.60∗∗ | 0.27∗∗ | 0.43∗∗ | 0.41∗∗ | 0.48∗∗ | 0.49∗∗ | — | |||||

| 9. Self-identity | 3.52 (0.98) | 1–5 | 0.24∗∗ | 0.50∗∗ | 0.29∗∗ | 0.29∗∗ | 0.48∗∗ | 0.37∗∗ | 0.42∗∗ | 0.58∗∗ | — | ||||

| 10. Trust | 3.71 (0.93) | 1–5 | 0.03 | 0.31∗∗ | 0.24∗∗ | 0.29∗∗ | 0.45∗∗ | 0.16∗∗ | 0.22∗∗ | 0.31∗∗ | 0.39∗∗ | — | |||

| 11. Perceived risk (cognitive) | 2.56 (0.75) | 1–5 | 0.23∗∗ | 0.18∗∗ | 0.12∗∗ | 0.21∗∗ | 0.15∗∗ | 0.24∗∗ | 0.17∗∗ | 0.28∗∗ | 0.15∗∗ | 0.10∗∗ | — | ||

| 12. Perceived risk (affective) | 2.9 (0.85) | 1–5 | 0.21∗∗ | 0.36∗∗ | 0.23∗∗ | 0.36∗∗ | 0.28∗∗ | 0.22∗∗ | 0.29∗∗ | 0.42∗∗ | 0.36∗∗ | 0.29∗∗ | 0.52∗∗ | — | |

| 13. Age | 59.09 (6.85) | 50–73 | 0.16∗∗ | −0.08 | −0.07 | 0.10∗∗ | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.10∗∗ | 0.06 | 0.01 | — |

- ∗p < 0.05.

- ∗∗p < 0.01.

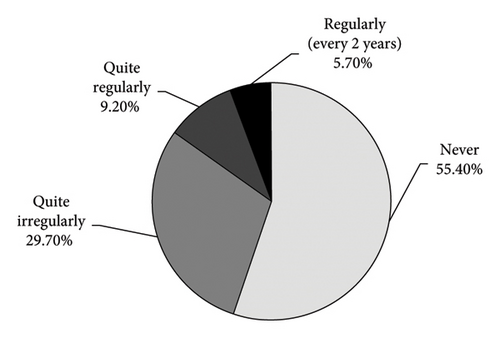

On average, participants reported a moderate level of all psychological variables except for AP, whose mean was slightly lower than the middle point (M = 2.28; SD = 1.14). Furthermore, respondents showed a very low score in the behaviour measure (M = 0.65; SD = 0.87), which reflects the fact that more than half of the sample (55.4%) did not participate in the CRCS even once (see Figure 2).

Moreover, all the correlations between the variables were positive and statistically significant, except for age—which only showed a weak positive correlation with behaviour and TI—and behaviour—which showed no significant correlation with attitude and TI. In particular, higher values were reported for AR and intention (r = 0.60), AR and SI (r = 0.58) and AP and CP (r = 0.57). Based on these results, we excluded serious multicollinearity concerns, as no correlation between the independent variables of the hypothesised model is > 0.80 [63].

4.2. SEM

A full SEM tested the hypothesised extended TPB model to explore the factors influencing respondents’ CRCS attendance. Indexes pointed to an overall acceptable fit of the global model, with CFI and TLI approaching the goodness of fit threshold (CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.042, SRMR = 0.068).

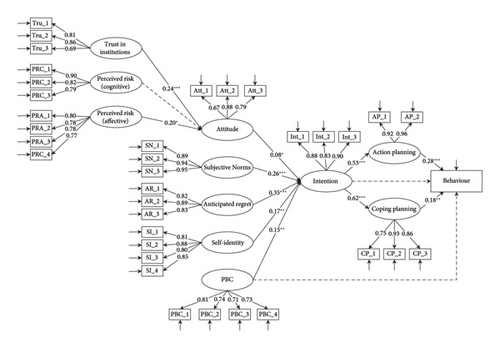

About the measurement model, since all standardised factor loadings were higher than 0.69 and statistically significant (all ps < 0.001), confirmatory factor analysis established that each manifested variable contributed appropriately to the overall model. Regarding structural relationships, almost all the hypotheses were confirmed (Figure 3). CRCS behaviour was positively predicted by AP (H4b) and CP (H5b), while the direct path from both intention (H1a) and PBC (H1b) was not confirmed. AP was predicted by intention (H4a), which also predicted CP (H5a). Furthermore, all hypothesised predictors of intention were confirmed (H1c-d, H2). Attitude, in turn, was predicted by TI (H3a) and the affective dimension of perceived risk (H3c), while the cognitive facet showed no statistically significant impact (H3b). Furthermore, we observed the following effects of control variables: behaviour was predicted by past vicarious experience with CRC (β = 0.14, p = 0.002) and previous knowledge about free public CRCS programs (β = 0.11, p = 0.024); intention was predicted by professing Catholic religion (β = 0.10, p ≤ 0.001), while the effect of past vicarious experience with CRC emerged as not significant. Overall, within this model, the variables explained a satisfactory amount of the variance in intention to attend CRCS (R2 = 59%) and in the related behaviour (R2 = 20%).

4.3. Mediation Analyses

Parallel mediation analysis was performed to verify the indirect effects of intention on behaviour (RQ1). The mediating effects of both AP (Indirect effect = 0.082; 95% CI [0.045, 0.123]) and CP (Indirect effect = 0.062; 95% CI [0.018, 0.107]) were confirmed. The direct path was still not significant, suggesting a full mediation. Furthermore, we investigated the difference between these effects, finding no statistically significant results (Effect = −0.025; 95% CI [−0.078, 0.028]).

5. Discussion and Conclusion

The present study tested the effectiveness of an extended TPB model in explaining CRCS attendance among citizens of the Campania region. Given the high mortality of CRC and the unsatisfactory rates of CRCS attendance, identifying the possible psychological antecedents of such behaviour is paramount to inform appropriate interventions.

While previous research has explored this topic to some extent, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no prior study has examined an integrated TPB model that simultaneously considers additional proximal predictors, distal predictors via attitude and variables bridging the intention–behaviour gap. The TPB has been successfully applied to various health behaviours, including CRCS attendance, providing valuable insights into its determinants [9]. However, achieving a more comprehensive integration of this theoretical model is still convenient, allowing a more nuanced understanding of the underlying processes through which each determinant operates.

Moreover, coherently to the goals of the MIRIADE project, investigating this phenomenon specifically among the population of South Italians, particularly within the geographic area of the Campania region, is relevant due to the observed disparities in access to public health CRCS compared to national data [5].

Our participants’ self-reported CRCS attendance aligns with the concerning statistics indicating low population rates [6]. More than half of the respondents (55.4%) reported never attending a CRCS, and less than 15% attend them regularly or quite regularly. On a descriptive level, these findings contrast with the high scores observed for intention, attitude and PBC. Notably, all psychological variables, except for AP, had mean scores higher than the midpoint. This is intriguing since all these variables are expected to positively predict behaviour and were explicitly targeted to CRC—except for SI, which generally targeted preventive behaviours. Thus, this could validate the role attributed by previous studies to practical barriers that could undermine participation in screening programs, such as logistic and/or healthcare-related factors [57, 64]. Unequivocally, this result empirically supports the existence of a broad gap between what people think and feel about attending CRCS and their actual behaviour [48, 65].

We confirmed almost all our hypotheses concerning the model. Two not significant paths concerned the direct predictive role of intention (H1a) and PBC (H1b) on behaviour. While previous studies have also indicated a marginal impact of PBC on cancer screening attendance, the nonsignificant prediction path that emerged from intention needs further investigation as it is inconsistent with prior evidence [66]. An understanding of this result could rely on the role of AP and CP as potential mediators of the intention–behaviour relationship. First, all the paths concerning these variables within the hypothesised model are confirmed (H4-5). In addition, our analyses confirmed full parallel mediation (RQ1), also suggesting that both variables could play an equally important role. Whether further confirmed among longitudinal studies, this finding would imply that people intending to participate in CRCS can benefit from a strategy involving detailed planning of when, where and how to perform the behaviour by overcoming potential barriers. Thus, a further implication would be that intention alone could not effectively translate into behaviour without proper and concrete planning. This interpretation of these findings is consistent with previous literature highlighting the joint effectiveness of AP and CP in helping individuals design a roadmap for action, enabling them to turn their intention into actual behaviour [67].

Notably, this result is also in line with the other few studies which have identified AP and CP as relevant factors in the context of cancer screening [54], despite no study, according to our knowledge, explicitly considered their role within the TPB model before. Besides, research about determinants of health behaviours has focused less on CP rather than AP as it appears to be more related to maintaining engagement, whereas AP is more relevant to the initial uptake of the considered behaviour [68]. For this reason, in a recent study investigating attitudes towards different intervention strategies among people who received an invitation to participate in CRCS, authors considered—and confirmed—the role of AP but not CP on behaviour [69]. On the one hand, Le Bonniec et al. [54] had already pinpointed the importance of CP as the key factor distinguishing profiles of highly intentioned people who attended CRCS from those who, with similar levels of intention, did not. On the other hand, their findings supported the role of CP and not AP. To address this topic, we speculate that in the current study the emerged predictive role of both AP and CP might be better understood in light of the peculiarities of the Campania context, in which the difficulties related to an overloaded health system [70] that is not always perceived as able to provide punctual answers to the needs of the population [71] could pose particular types of barriers not only to those who are approaching to this practice for the first time but also to highly intentioned citizens who want to keep on being screened, also making the planning of practical coping strategies especially salient for all. This would also be coherent with studies showing that factors associated with life difficulties are better predictors of action than intention [49]. Future investigations could empirically test this interpretation by explicitly considering the possible practical barriers that Campania citizens could have to face.

Moreover, our findings confirmed all hypotheses about the considered predictors of intention (H1c-e, H2). As expected, intention to attend CRCS depends on attitude towards the screening, SN, PBC, AR and SI. Particularly, PBC emerging as a significant predictor of intention but not of behaviour could suggest that, although participants felt in control when forming their intention to undergo CRCS, this perception may diminish during the course of action due to contextual challenges.

Among the other predictors of intention, the strongest was AR, followed by SN. This result is consistent with previous research integrating AR within the TPB model, which has already confirmed its relevance for various preventive behaviours such as vaccine uptake [19, 20] and cervical screening attendance [24]. Regarding CRCS attendance, the role of AR as a predictor is in line with what has been found by previous research [23, 72] and, in particular, with those studies that indicated it as a useful variable to manipulate in interventions aimed at successfully increasing intention [23, 49].

Furthermore, SN emerged as the second strongest predictor of intention. Such evidence indicates that, as expected, the positioning of significant others towards CRCS can prompt the development of individuals’ intention to attend them [57].

The hypothesis suggesting SI as another important intervening factor is also confirmed. While, as previously discussed, its integration within the TPB model is far from being a novelty, our results support its applications in the cancer screening domain, which is especially characterised by a lack of studies investigating the predictive role of SI on the intention to attend CRCS within a TPB model. Our results are in line with Booth et al. [32], which confirmed the relevance of SI in predicting intentions to test for chlamydia, while are not consistent with Mason and White [33], who, on the contrary, found SI as a nonsignificant predictor in the context of breast self-examination. This can be explained by taking into account that, in Booth et al. [32], items referring to SI were specific to the behaviour they were investigating. Otherwise, in Mason and White’s study [33], SI was operationalised by generally referring to the broader role of engaging in health-promoting behaviours. In the present study, a different approach was employed: SI was assessed as the salience of preventive behaviour for the individual. Thus, our approach could be considered intermediate between the two considered cases according to the level of specificity of the behaviour held in consideration. If further confirmed, this finding can pose particularly relevant implications for future interventions, as it can inform the application of a wide range of manipulation techniques (e.g., [73]) that could leverage the salience of a broader range of roles and behaviours (precisely, all the prevention-related ones) to strengthen participants’ SI instead of focusing only on CRCS participation.

Further, attitude was the weakest predictor of intention. This result is inconsistent with the TPB literature on health-related behaviours, often identifying it as a key antecedent [36]. In the context of our study, such evidence could be attributed to the extremely high mean of attitude, which could result in a ceiling effect: as previously discussed, Campania citizens seem pretty aware of the benefits associated with CRCS, regardless of their actual behaviour. From a practical point of view, this evidence also suggests that interventions aimed at increasing intention should better be focused on other, more prompting variables like AR or SN, rather than targeting an increment of the already positive attitude towards the screening campaign.

Finally, we investigated the role of three predictors of attitude towards CRCS: TI (H3a) and perceived risk in both cognitive (H3b) and affective facets (H3c). Regarding TI, our findings confirmed its potential impact on attitude, in line with the perspective supported by qualitative studies pointing out that participation in a population-based screening program such as CRCS relies on a trust-based decision [41, 42, 74].

However, regarding the role of perceived risk in predicting attitude, the findings are not as straightforward. The affective—but not the cognitive—facet of risk emerged as a significant predictor of attitude. As discussed before, many studies investigating CRCS have considered only the cognitive component [10], leaving out the role of worry about the threat. On the contrary, in our findings, this is the only facet to show a significant predictive impact, enhancing the importance of emotions in the preventive behaviours domain [75] and suggesting that interventions aimed at increasing attendance rate could benefit from working on how worried people feel about their risk of contracting CRC [76]. Interestingly, most of the literature about CRCS and risk perception has focused on different and specific operationalisations and tested its role as a direct determinant of behaviour. In this sense, further empirical studies and theoretical investigations could build on these findings and shed new light on the ways these components of risk perception can effectively predict CRCS attendance and whether it is worth considering different paths for each influence.

5.1. Limitations

The current study is not free of limitations and prompts future investigations. First, the study design: its cross-sectional nature prevents drawing causal conclusions and also makes it impossible to reject the hypothesis of reverse relations within the considered paths (e.g., [77]). Second, the sample. We employed a nonprobabilistic sampling, so the findings cannot be generalisable to the entire population. Also, as we only had access to completely filled-in questionnaires, we could not compute response and completion rates, or deal with missing data in any way. Furthermore, in defining the target population of the study we have not considered diseases that could affect the screening routine other than a previous experience with cancer (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease). Third, the measured: self-report items could be ineffective in limiting the effect of social desirability. This is particularly relevant for CRCS behaviour, which future studies could assess by employing objective measures. Finally, the variable selection: despite the accurate literature analysis, it is impossible to exclude other factors that could mediate or even moderate the considered paths (e.g., intention strength could moderate its effects on behaviour; [78]). Also, it is worth noting that our model focuses primarily on individual-level variables, but literature has also shown that some structural and institutional factors could also play important roles in predicting CRCS behaviour [79]. A final crucial limitation concerns the employing of mediation analyses within cross-sectional data. Despite the existence of a wide literature testing mediation hypotheses in this way [36], scholars have raised concerns about the causal interpretations of such analyses [80, 81], suggesting that, as the hypothesis of mediation rely on a clear temporal sequence and cross-sectional data cannot definitively establish the temporal order of variables, the interpretation of these analyses could lead to biased estimates of mediation effects. Thus, to exclude the case, future studies should further validate these findings within longitudinal studies.

5.2. Practical Implications

Net of the mentioned limitations, our study achieved its goal of obtaining an empirical understanding of the determinants of CRCS attendance in a very precise geo-cultural context (namely, Campania Region, Italy), posing some key implications for the subsequent planning of an intervention strategy to finally improve the related cancer screening participation rate. In this sense, our finding about the tested predictors of CRCS behaviour will orienteer the next steps of the MIRIADE project [82], whose first objective will test the efficacy of the same model in predicting the participation in cervical and breast cancer screening. In turn, this will affect the subsequent steps as the confirmed predictors of behaviours will be employed as key variables to identify data-driven profiles of citizens, which will be the object of tailored intervention strategies that will tap on the psychosocial features (in terms of combination of scores on these variables) characterizing each profile. Furthermore, the understanding of the antecedents of CRCS offered within this cross-sectional study can offer insights for shaping local healthcare operators’ skills [83], as these professionals will be trained to positively interact with the users and to leverage those key elements which could actually make more likely that they will successfully engage in periodic cancer screenings, such as AP and CP.

Outside the specific implications of the study within the MIRIADE Project, more generally, future intervention can benefit from the emerged findings suggesting the psychological variables whose impact on behaviour should be tested in future interventions aimed at increasing attendance. Thus, according to this study, it could be possible to impact the attitude towards CRCS by working on TI and perceived affective risk. Still, a more effective strategy could point to increase intention, with interventions focused on AR and SN or even on a broad SI that encompasses the general importance attributed to prevention. Furthermore, to directly impact behaviour, future studies should experimentally test the role of both AP and CP in helping citizens translate intention into actual behaviour. As mentioned previously, this is not obvious in the case of those who have to implement the behaviour for the first time since it seems that, although CP is a process more classically linked to the maintenance of the action, its role in predicting CRCS attendance still appears to be relevant [54], and should be further tested within experimental designs.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research was supported by Regional Prevention Plan (PRP Campania 2020–2025 Ministry of Health, Italy), project MIRIADE (DGRN 403, 9/12/2020).

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.