The Impact of Household Resilience and Dietary Diversity on Child Malnutrition

Abstract

This study examines the impact of household resilience and dietary diversity on child malnutrition in Pakistan using data from the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) 2017–2020. By analyzing the relationship between household resilience, minimum dietary diversity (MDD), and malnutrition indicators—stunting, underweight, and wasting—the findings reveal a significant association. Higher household resilience is linked to better dietary diversity and lower malnutrition rates, with resilient households showing reduced prevalence of stunting, underweight, and wasting among children. MDD emerges as a fundamental protective factor, with children consuming minimum diverse foods demonstrating improved nutritional outcomes. Particularly, regional disparities are evident, with provinces such as Sindh, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and Balochistan exhibiting higher malnutrition rates compared to Punjab. The study underscores the importance of enhancing household resilience and dietary diversity to combat malnutrition in Pakistan, advocating for targeted interventions to improve child health outcomes.

1. Introduction

Child malnutrition remains one of the most critical public health challenges worldwide, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [1, 2]. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines malnutrition as deficiencies, excesses, or imbalances in a person’s intake of energy and nutrients. In children, malnutrition manifests in various forms, including stunting (chronic undernutrition), wasting (acute undernutrition), and underweight (a combination of both acute and chronic undernutrition) [3]. These conditions can have long-lasting effects on a child’s physical [4], cognitive [5], and emotional development [6], contributing to a cycle of poverty [7] and inequality [8] that extends into adulthood and across generations [9]. Globally, significant progress has been made in reducing child malnutrition, though the burden remains substantial [10]. According to the United Nations Children’s Fund, an estimated 144 million children under the age of five were stunted, 47 million were wasted, and 14.3 million were severely wasted in 2020 [11]. The prevalence of malnutrition is particularly high in South Asia, where socioeconomic disparities, food insecurity, and limited access to healthcare services exacerbate the problem [12]. In this context, understanding the determinants of child malnutrition is essential for designing effective interventions and policies to improve child health outcomes.

In recent years, the concept of household resilience has gained prominence as a critical factor influencing child nutrition [13, 14]. Household resilience refers to the ability of a household to anticipate, absorb, and recover from shocks or stresses [15], such as economic hardship [16], food insecurity, or health crises [17, 18]. Resilient households are better equipped to provide their children with adequate nutrition, reduce food insecurity, and ensure access to essential healthcare services [19]. Conversely, vulnerable households with low resilience are more likely to experience nutritional deficiencies, contributing to higher rates of child malnutrition [20–27]. The role of household resilience in mitigating the impact of socioeconomic shocks on child nutrition has been increasingly recognized in both global and regional contexts [28, 29].

Dietary diversity, or the variety of food groups consumed by a household, is another crucial determinant of child nutrition [30, 31]. The minimum dietary diversity (MDD) is a key indicator used to assess the nutritional status of children, particularly those under the age of two [32, 33]. MDD refers to the number of food groups a child consumes, with a higher number of food groups correlating with better nutritional outcomes [32]. Children who consume a diverse range of foods, including grains, legumes, vegetables, fruits, and animal-based products, are more likely to receive a balanced intake of essential nutrients, which reduces the risk of stunting, underweight, and wasting [34, 35]. Conversely, limited dietary diversity increases the risk of nutrient deficiencies, leading to malnutrition and its associated health consequences [36, 37].

The relationship between household resilience, MDD, and child malnutrition is complex and complicated. The households with better access to economic resources, education, and healthcare tend to have higher dietary diversity and are more capable of ensuring that their children receive adequate nutrition [38]. On the other hand, households with limited resources and fewer coping strategies are often forced to rely on cheaper, energy-dense foods that are nutritionally inadequate, leading to poor dietary diversity and higher rates of malnutrition [39, 40]. Therefore, it is essential to explore how the combined effects of household resilience and dietary diversity influence child malnutrition outcomes.

The situation in Pakistan provides a particularly relevant context for examining the relationship between household resilience, MDD, and child malnutrition. Pakistan has one of the highest rates of child malnutrition in South Asia [41], with a significant proportion of children under five suffering from stunting, underweight, and wasting [42, 43]. These malnutrition indicators are exacerbated by a range of factors, including poverty, limited access to healthcare, and regional disparities in infrastructure and services [43, 44]. In rural areas, where access to nutritious food and healthcare services is limited, malnutrition rates are higher compared to urban areas [45, 46]. Furthermore, regional differences within Pakistan, particularly between provinces such as Punjab, Sindh, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK), and Balochistan, highlight the disparities in resilience and dietary diversity that contribute to variations in malnutrition rates [47]. Punjab, as the most populous and economically developed province [48], generally exhibits lower rates of child malnutrition compared to other provinces. This can be attributed to relatively better access to healthcare, education, and food security programs [49]. In contrast, Sindh and Balochistan have higher malnutrition rates, driven by factors such as poverty, food insecurity, and inadequate healthcare infrastructure. KPK, while showing improvements in recent years, still faces challenges related to political instability and access to essential services [50]. These regional disparities underscore the need for targeted interventions that address the unique challenges faced by households in different provinces.

This study aims to investigate the relationship between household resilience, dietary diversity, and child malnutrition in Pakistan. It specifically examines how these factors interact to influence the prevalence of malnutrition indicators—stunting, underweight, and wasting—across different provinces. The hypothesis underlying this study is that higher household resilience is associated with better dietary diversity, which in turn reduces the likelihood of malnutrition in children.

The novelty of this study lies in its comprehensive approach to examine the combined effects of household resilience and dietary diversity on child malnutrition within a country-specific context. By focusing on Pakistan, the study provides valuable insights into the regional disparities in malnutrition and the role of household resilience and dietary diversity in mitigating these disparities. Furthermore, the study’s findings have important implications for public health policy, particularly in developing strategies to improve household resilience and dietary diversity in vulnerable regions. Ultimately, addressing the underlying determinants of malnutrition, such as household resilience and dietary diversity, is the key for reducing the prevalence of child malnutrition and improving the overall health and well-being of children in Pakistan.

2. Methodology

-

Study Design: This study employs a cross-sectional design to analyze data from the MICS Wave 6, conducted across the four provinces of Pakistan.

-

Study Site: The study covers the four provinces of Pakistan: Punjab, Sindh, KPK, and Balochistan, and the study provinces are representative of the country’s geographic and socioeconomic diversity.

-

Data Collection: Data were collected through household surveys administered by trained enumerators as part of the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) conducted by UNICEF. The survey collected detailed demographic information, household characteristics, and child health indicators. For more detailed information, refer to the MICS Wave 6 data source (UNICEF).

-

Study Population: The study focuses on children aged 6–23 months. Inclusion criteria included all children within the specified age range whose complete data on key variables (malnutrition indicators, dietary diversity, and Household Resilience Index) were available. Exclusion criteria included children outside the age range and those with incomplete or missing data. In total, the sample size ranges from 10,872 to 11,487 children, depending on the regression model specifications.

3. Key Variables

-

Child Malnutrition Indicators: The dependent variable of the study is malnutrition, defined by the WHO [51] as the state of being undernourished or lacking essential nutrients vital for appropriate growth and development, measured using three key indicators: stunting (height-for-age), underweight (weight-for-age), and wasting (weight-for-height). Stunting (Height-for-Age): This indicator measures linear growth and identifies children who are short for their age. Stunting reflects chronic malnutrition and prolonged nutritional deficiencies. Children whose height-for-age z-score falls below −2 standard deviations from the median of the WHO growth standards are classified as stunted. These indicators are binary variables coded as one when the child exhibits the condition and zero otherwise. Underweight (Weight-for-Age): This indicator reflects both acute and chronic malnutrition. It identifies children who have a low weight for their age, suggesting either recent illness or long-term poor nutritional intake. Children whose weight-for-age z-score falls below −2 standard deviations from the median of the WHO growth standards are classified as underweight. These indicators are binary variables coded as one when the child exhibits the condition and zero otherwise. Wasting (Weight-for-Height): This indicator measures acute malnutrition and identifies children who have a low weight for their height. Wasting signals’ immediate nutritional deficiencies or the effects of recent illness are associated with severe weight loss. Children whose weight-for-height z-score falls below −2 standard deviations from the median of the WHO growth standards are classified as wasted. These indicators are binary variables coded as one when the child exhibits the condition and zero otherwise.

-

MDD: MDD was computed based on the variety of food groups consumed by a child within the preceding 24 h. The eight dietary groups considered were as follows: grains, roots, and tubers; legumes and nuts; dairy products; meat, poultry, and fish; eggs; vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables; other fruits and vegetables; and fats and oils. Each food group was represented by a binary variable indicating consumption (one for consumed and zero for not consumed). The average number of groups consumed was coded as zero if fewer than four groups were consumed and one if four or more groups were consumed. Ultimately, MDD was coded as a binary variable: one if the child consumed four or more food groups and zero otherwise.

-

Household Resilience Index: This is constructed in two steps: first, using principal component analysis (PCA) to combine socioeconomic indicators into subindices, and second, averaging these subindices to quantify households’ resilience. The index includes five subindices: Access to Basic Services (ABS), which includes access to water, sanitation, and electricity; Assets (AST), encompassing ownership of items such as televisions, radios, telephones, refrigerators, bicycles, motorbikes, computers, and housing quality (roof, floor, or wall materials); Adaptive Capacity (AC), measured by household education levels and size; Sensitivity (SEN), considering mortality rates and disabilities among children and mothers within the household; and Policy and Institutional Support, measured by access to social transfers and health insurance. Standardized variables were combined using the PCA to produce a continuous index ranging from low to high resilience.

-

Control Variables: These include child’s gender (male = 1 and female = 0), area of residence (rural = 1 and urban = 0), and region of residence (categorical: 1 = Punjab, 2 = Sindh, and 3 = KPK, 4 = Balochistan), incorporated to isolate the specific impact of household resilience and MDD on child malnutrition indicators.

-

Data Management: Data management involved cleaning the dataset to remove any incomplete or inconsistent records. Variables were standardized to z-scores to ensure comparability, and the resulting dataset was prepared for analysis using Stata 18 statistical software.

-

Data Analysis: Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the distribution of variables across provinces. Inferential statistics, including structural equation modeling (SEM), were employed to assess the relationships between household resilience, MDD, and child malnutrition indicators. The growth standard used in the analysis was the WHO Child Growth Standards.

-

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by the UNICEF, which oversees ethical compliance in the research involving human participants.

4. Results

The results of this study, as presented in Table 1, reveal key patterns and significant associations between MDD, child malnutrition indicators (underweight, stunting, and wasting), and various socioeconomic factors across different provinces in Pakistan. The analysis provides insights into how these factors vary by region, gender, and access to resources, using binary logistic regression models.

| Variables | Categories | Punjab | Sindh | KPK | Balochistan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum dietary diversity (MDD) | No | 2362 (79.7%) | 2001 (83.4%) | 3025 (84.8%) | 2332 (81.2%) |

| Yes | 601 (20.3%) | 398 (16.6%) | 544 (15.2%) | 541 (18.8%) | |

| Gender | Female | 1473 (49.7%) | 1177 (49.1%) | 1742 (48.8%) | 1473 (51.3%) |

| Male | 1490 (50.3%) | 1222 (50.9%) | 1827 (51.2%) | 1400 (48.7%) | |

| Area of residence | Rural | 1669 (56.3%) | 1273 (53.1%) | 3091 (86.6%) | 2170 (75.5%) |

| Urban | 1294 (43.7%) | 1126 (46.9%) | 478 (13.4%) | 703 (24.5%) | |

| Stunting | No | 2150 (76.0%) | 1196 (53.8%) | 2238 (66.7%) | 1239 (50.3%) |

| Yes | 680 (24.0%) | 1028 (46.2%) | 1118 (33.3%) | 1223 (49.7%) | |

| Underweight | No | 2325 (80.8%) | 1421 (60.5%) | 2754 (78.2%) | 1729 (63.1%) |

| Yes | 551 (19.2%) | 928 (39.5%) | 769 (21.8%) | 1010 (36.9%) | |

| Wasting | No | 2586 (90.8%) | 1823 (79.3%) | 2931 (85.8%) | 2142 (81.4%) |

| Yes | 262 (9.2%) | 475 (20.7%) | 487 (14.2%) | 488 (18.6%) | |

| Household Resilience Index | 0.48 (0.14) | 0.38 (0.17) | 0.39 (0.14) | 0.36 (0.15) | |

From Table 1, we observe the distribution of key variables across the four provinces of Pakistan. The prevalence of children with inadequate MDD is the highest in KPK, where 84.8% of children did not meet the recommended dietary diversity, followed by Sindh (83.4%) and Punjab (79.7%). Balochistan has a relatively lower percentage of children with inadequate MDD (81.2%). This pattern reflects regional differences in access to nutrition and food diversity, which could influence malnutrition outcomes.

Gender distribution is fairly balanced across the provinces, with males comprising a slightly higher percentage in all provinces, except in Balochistan, where females make up a slightly higher proportion. Regarding the area of residence, a higher percentage of children in rural areas face malnutrition-related challenges compared to urban areas. For instance, 86.6% of children in KPK live in rural areas, while Balochistan has 75.5% of children in rural areas. This suggests a correlation between rural residency and higher malnutrition risks due to limited access to healthcare and nutrition services.

The malnutrition indicators (stunting, underweight, and wasting) also show substantial variation. Stunting, which is a chronic form of malnutrition, is the highest in Balochistan (49.7%), followed by Sindh (46.2%). Similarly, underweight prevalence is most severe in Sindh (39.5%), followed by Balochistan (36.9%). Wasting, an acute form of malnutrition, is most prevalent in Sindh (20.7%), indicating that more children in this province are experiencing recent and severe weight loss due to inadequate food intake or illness.

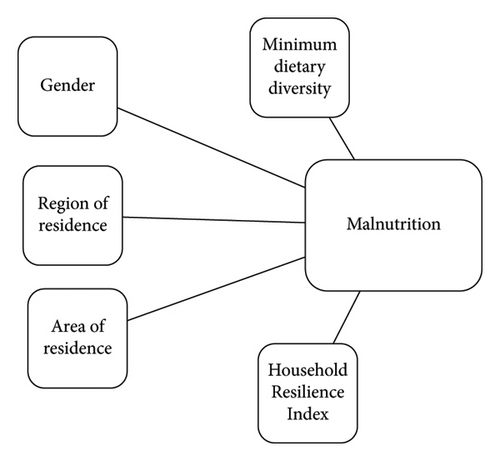

Figure 1 illustrates the SEM path analysis of the Household Resilience Index and the integration of control variables within the theoretical framework. The results of the SEM path analysis, shown in Table 2 of the household resilience regression models, highlight several key factors influencing child malnutrition outcomes.

| Variables | Underweight | Stunting | Wasting | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum dietary diversity (MDD) | No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.963∗∗∗ | 0.976∗∗ | 0.979∗∗ | |

| (0.0102) | (0.0114) | (0.00865) | ||

| Household Resilience Index | 0.628∗∗∗ | 0.631∗∗∗ | 0.853∗∗∗ | |

| (0.0187) | (0.0207) | (0.0210) | ||

| Gender | Male | Reference | ||

| Female | 0.910∗∗∗ | 0.939∗∗∗ | 0.959∗∗∗ | |

| (0.00736) | (0.00841) | (0.00645) | ||

| Area of residence | Urban | Reference | ||

| Rural | 1.018∗ | 1.017 | 1.008 | |

| (0.0102) | (0.0112) | (0.00838) | ||

| Region of residence | Punjab | Reference | ||

| Sindh | 1.165∗∗∗ | 1.190∗∗∗ | 1.102∗∗∗ | |

| (0.0146) | (0.0163) | (0.0114) | ||

| KPK | 0.976∗∗ | 1.045∗∗∗ | 1.033∗∗∗ | |

| (0.0111) | (0.0130) | (0.00972) | ||

| Baluchistan | 1.126∗∗∗ | 1.221∗∗∗ | 1.076∗∗∗ | |

| (0.0136) | (0.0163) | (0.0108) | ||

| Constant | 1.585∗∗∗ | 1.630∗∗∗ | 1.208∗∗∗ | |

| (0.0310) | (0.0351) | (0.0196) | ||

| N | 11,487 | 10,872 | 11,194 | |

- Note: Standard errors in parentheses.

- ∗∗∗p < 0.01.

- ∗∗p < 0.05.

- ∗p < 0.1.

Children with better dietary diversity (MDD = Yes) have significantly lower risks of being underweight, stunted, or wasted. For underweight, the odds ratio is 0.963 (p < 0.01), indicating that children with higher MDD are less likely to be underweight compared to those with inadequate MDD. Similarly, the odds of stunting and wasting are lower for children with sufficient dietary diversity, with odds ratios of 0.976 (p < 0.05) and 0.979 (p < 0.01), respectively.

Household resilience, which is measured based on economic status and ABS, shows a strong inverse relationship with malnutrition. The Household Resilience Index is significant for all three forms of malnutrition. The odds ratio for underweight is 0.628 (p < 0.01), stunting is 0.631 (p < 0.01), and wasting is 0.853 (p < 0.01). This suggests that households with higher resilience are less likely to have malnourished children.

Female children have lower odds of being underweight, stunted, or wasted compared to male children. The odds ratios for female children are 0.910 (p < 0.01) for underweight, 0.939 (p < 0.01) for stunting, and 0.959 (p < 0.01) for wasting, indicating that gender plays a significant role in malnutrition, with female children being less likely to experience severe malnutrition.

Children in rural areas are at a higher risk of malnutrition compared to their urban counterparts. The odds of being underweight for rural children are 1.018 (p < 0.1), stunted children have an odds ratio of 1.017, and wasting in rural children has an odds ratio of 1.008. Although the effect for stunting and wasting is not statistically significant, the trend suggests a higher likelihood of malnutrition in rural areas, where access to nutritious food and healthcare services may be limited.

Provincial differences also emerge as significant in determining child malnutrition. Children from Sindh, KPK, and Balochistan have higher odds ratios of being underweight, stunted, or wasted compared to those from Punjab. In Sindh, the odds ratios for underweight, stunting, and wasting are 1.165 (p < 0.01), 1.190 (p < 0.01), and 1.102 (p < 0.01), respectively. Similarly, children from KPK and Balochistan are at a higher risk of malnutrition than those in Punjab, with odds ratios ranging from 1.033 (p < 0.01) to 1.221 (p < 0.01).

The findings from the analysis highlight the significant impact of socioeconomic and regional factors on child malnutrition in Pakistan. Key factors such as dietary diversity, household resilience, gender, and area of residence all play pivotal roles in determining the risk of malnutrition. Children in regions with higher socioeconomic challenges, such as Sindh, KPK, and Balochistan, exhibit higher levels of stunting, underweight, and wasting, emphasizing the need for region-specific interventions that address both immediate and long-term nutritional needs. These results reinforce the importance of improving MDD and household resilience to mitigate the risks of child malnutrition across different provinces in Pakistan.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study underscore the critical role of MDD and household resilience in mitigating child malnutrition in Pakistan. These results align with the previous research [42, 52, 53], emphasizing the importance of dietary diversity and socioeconomic stability in improving child health outcomes [54].

Our study reveals that children who meet the MDD threshold are significantly less likely to be underweight, stunted, or wasted. This finding is consistent with previous studies, such as those by Barrea et al. [55] and Marshall et al. [56], which highlight the protective role of diverse diets in providing essential nutrients for growth and development. In Pakistan, dietary diversity is often constrained by economic limitations and cultural preferences, particularly in rural areas where households rely on a narrow range of cheap, energy-dense foods [57]. The association between MDD and improved nutritional outcomes suggests that interventions aimed at enhancing dietary diversity could have a substantial impact on reducing malnutrition rates.

Household resilience, measured through the Household Resilience Index, shows a strong inverse relationship with child malnutrition. Higher household resilience is associated with significantly lower of children being underweight, stunted, or wasted. This finding aligns with the research by Sunday et al. [18] and Ado et al. [58], which emphasize the importance of economic stability and access to essential services in mitigating the adverse effects of food insecurity and malnutrition. In Pakistan, resilient households are better equipped to provide adequate nutrition and healthcare, reducing the risk of malnutrition [43].

The study also highlights gender disparities in malnutrition outcomes, with female children exhibiting lower odds ratios of being malnourished compared to male children. This finding contrasts with some global studies, such as the study by Biswas et al. [59], which report higher malnutrition rates among female children in South Asia. However, our results may reflect cultural practices in Pakistan that prioritize the nutrition of males or indicate gender-based caregiving patterns that do not favor female children [60]. Further research is needed to explore the underlying reasons for these gender disparities and to ensure that both male and female children receive adequate nutrition.

Significant regional disparities in child malnutrition are evident across Pakistan’s provinces. Sindh and Balochistan exhibit higher rates of stunting, underweight, and wasting compared to Punjab. These findings are consistent with prior research indicating that socioeconomic instability, food insecurity, and limited access to healthcare exacerbate malnutrition in underdeveloped regions. Sindh, in particular, faces challenges related to internal displacement, natural disasters, and political instability, which disrupt access to nutrition and healthcare. Balochistan, with its significant rural population and lower access to services, also shows high levels of malnutrition, underscoring the need for targeted interventions in these provinces [50].

Conversely, Punjab’s relatively better performance in reducing malnutrition can be attributed to its more developed infrastructure, better access to healthcare, and stronger economic base [61]. These regional disparities highlight the importance of context-specific interventions that address the unique challenges faced by households in different provinces. The findings of this study are in line with the global research on the determinants of child malnutrition. Studies from other LMICs also emphasize the importance of dietary diversity and household resilience in improving child health outcomes. For instance, a study by Rahman et al. [62] in South Asia found that economic stability and access to diverse diets are crucial for reducing malnutrition rates. Similarly, the research by Sohel et al. [63] in Bangladesh highlights the protective role of household resilience in mitigating the impact of food insecurity on child nutrition.

The limitations of this study are primarily attributed to the cross-sectional nature of the data, which restricts our ability to establish causality between variables such as household resilience, dietary diversity, and child malnutrition. To better understand the temporal relationships between these factors, longitudinal studies are needed. Additionally, the reliance on self-reported data may introduce biases or inaccuracies, potentially affecting the robustness of our findings related to dietary diversity and household resilience. These limitations highlight the need for more comprehensive data and methodologies to fully capture the complexities of child malnutrition.

The findings of this study have significant policy implications for addressing child malnutrition in Pakistan. First, there is a need for region-specific interventions that address the household resilience capacity determinants of malnutrition. Provinces such as Sindh and Balochistan would benefit from targeted investments in infrastructure, healthcare, and nutrition programs that cater to their specific needs. Additionally, policies that promote household resilience through economic support could mitigate the impact of food insecurity and improve child nutrition. Improving dietary diversity is another precarious area for intervention. Programs that enhance access to diverse and nutritious foods, particularly in rural and underserved areas, can significantly reduce malnutrition rates. Nutrition education programs that promote the importance of diverse diets and provide practical guidance on incorporating various food groups into children’s meals are essential. Lastly, gender-sensitive policies should be developed to address the nutritional needs of both male and female children. It is essential to ensure that all children have equal access to nutritious food and healthcare services.

This study underscores the critical role of household resilience and dietary diversity in reducing child malnutrition in Pakistan. The findings highlight the need for targeted interventions that address regional disparities and promote household resilience capacity stability and access to diverse, nutritious foods. By implementing policies that enhance household resilience, improve dietary diversity, and ensure gender equality in nutrition, significant progress can be made in struggling child malnutrition in Pakistan.

Ethics Statement

The authors have nothing to report.

Consent

The authors have nothing to report.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The study was funded by Nanyang Normal University Project (Grant number: 2024BS008).

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the support of the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2025R997), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data are openly available in a public repository that issues datasets with DOIs at https://mics.unicef.org/surveys. Cleaned data used in the analysis are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.