Digital Literacy, Intergenerational Relationships, and Future Care Preparation in Aging Chinese Adults in Hong Kong: Does the Gender of Adult Children Make a Difference?

Abstract

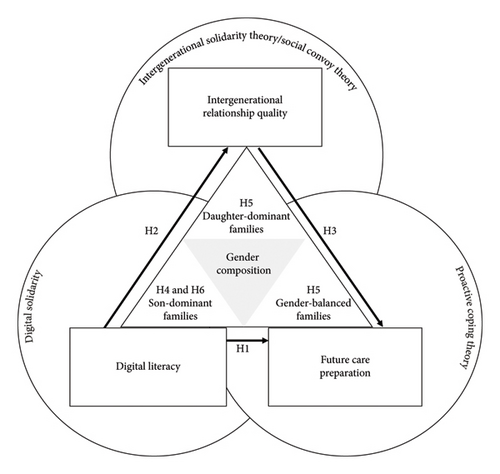

As populations continue to age, the demand for future care is expected to increase. Future care preparation is a form of proactive coping that can prevent or offset potential stressors related to the changing needs of older adults. Acquisition and preservation of resources are essential for effective proactive coping. Integrating social convoy theory, intergenerational solidarity theory, and proactive coping theory, this study assessed the level of digital literacy, quality of intergenerational relationships, and future care preparation in son-dominant, daughter-dominant, and gender-balanced families. The direct and indirect effects of digital literacy on future care preparation through intergenerational relationships were also examined. Data from 3,626 participants with at least one adult child were drawn from the Panel Study of Active Aging and Society conducted in 2022, which was designed to be a biennial study conducted with a representative sample of individuals aged 50 years and older in Hong Kong. Aging parents in son-dominant families had the highest levels of digital literacy; those in daughter-dominant families had the highest levels of intergenerational relationship quality and future care preparedness. Intergenerational relationship quality mediated the relationship between digital literacy and future care preparation in all three types of families, but the effect sizes differed. These findings suggest a need to enhance the digital literacy of aging adults and improve their intergenerational relationships, thereby assisting them to prepare in advance for their future care needs.

Summary

- •

This study examines the relationship between digital literacy, intergenerational relationships, and future care preparation among aging Chinese parents in Hong Kong.

- •

A key finding is that digital literacy influences aging adults’ future care preparation directly and through the quality of intergenerational relationships.

- •

The findings of this study accentuate the importance of digital literacy in older adults’ preparation for future care needs and highlight the significant role played by adult children.

- •

To ensure that older adults receive adequate informational and technical support to support future care preparation plans, the government, service providers, and gerontology practitioners should provide sufficient resources and training.

1. Introduction

Global population aging, driven by lower fertility rates and longer life expectancies, is increasing demand for future care services. According to the Census and Statistics Department [1], approximately one in every three persons will be an older adult in Hong Kong in 2038. In particular, those aged 75 and above will increase from 0.57 million to 1.40 million [2]. The increasing demand for care due to the deteriorating health of the growing aging population has emerged as a significant stressor that affects individuals, their families, and society. It becomes increasingly crucial for older adults and their families to proactively engage in the preparation for future care needs. Future care preparation, which involves thoughts, planning behaviors, and decisions made in anticipation of a forthcoming period in which comprehensive care and support become necessary due to aging and declining health, can help alleviate stress, foster responses to care transitions, and optimize care arrangement and quality of later life [3, 4].

Mobile technology usage among older adults has been increasing. The amount of time older adults spend on the Internet has risen [5], as has their reliance on digital devices to maintain social connections and access information [6, 7]. The social benefits of digital technology appear particularly significant for older adults when opportunities for face-to-face communication are limited [8]. Intergenerational relationships, serve as a vital source of social contact and support for older adults, can help alleviate depression and isolation, and digital communication plays a crucial role in facilitating these relationships [9]. Digital literacy and positive intergeneratinal relationships are expected to enhance the preparation of care for older adults by facilitating access to online information and improve communication between generations. The present study examines how digital literacy directly and indirectly influences aging adults’ (aged 50 years and over) care preparation through intergenerational relationships and the gender role of their adult children. The study findings can serve as a reference for the development of policies and interventions that can improve digital literacy, intergenerational relationships, and care preparation in later life.

2. Future Care Preparation and Proactive Coping Resources

Future care preparation, involving awareness of future care needs and engagement in preparing for future care, is influenced by an individual’s resources and ability to plan for the future [4, 10]. Previous studies have found that being female, having a higher educational level, and possessing a higher socioeconomic status and better intergenerational relationships are associated with increased levels of care planning and filial care expectations [3, 10, 11]. Moreover, future care preparation with family members is crucial when adult children are expected to help their parents navigate complex later-life care decisions [12].

Proactive coping theory suggests that efforts made in anticipation of potentially stressful events can prevent these events or modify their form before they occur [13, 14]. Empirical evidence indicates that preparing for future care enables older adults to better manage the challenges related to aging, reduce stress, and optimize care [15–18]. Furthermore, when older adults prepare for future care, it can alleviate the stress experienced by (potential) caregivers and reduce their burden of future care [19].

Effective proactive coping requires the acquisition and preservation of resources such as planning skills, family support, and cooperation [13, 14]. Intergenerational relationships and digital literacy are essential for effective future care preparation. This study examines the association between older adults’ digital literacy and their future care preparation, as well as the influence of intergenerational relationships on this association.

2.1. Intergenerational Relationships as an Essential Relational Resource for Future Care Preparation

Social convoy theory provides a valuable framework for understanding the dynamic network of social relationships that provide individuals with essential support, resources, and protection throughout their lives [20]. This network, or “convoy,” can evolve over time in response to life stages and changing needs. The convoy delivers emotional, informational, and practical support, which can significantly influence an individual’s coping strategies and overall well-being. As parents age, adult children may take on greater caregiving responsibilities, playing a crucial role in determining the well-being of older adults and necessitating adjustments in the convoy [21]. Evidence shows that positive and intimate relationships, along with bidirectional support exchanges, are associated with reduced social isolation and loneliness and improved well-being in older parents [22–24].

The intergenerational solidarity model [25, 26] describes intergenerational relationships through six dimensions of solidarity: affective, associational, consensual, functional, normative, and structural. The solidarity theory characterizes the significant affective bonds between generations by examining the sentiments, behaviors, attitudes, values, and structural arrangements that connect the generations [27]. Recently, by combining conflict and ambivalent dimensions with solidarity, the Intergenerational Relationship Quality Scale for Aging Chinese Parents (IRQS-AP) [28] has been developed to measure the relationship quality between older adults and their adult children.

Close intergenerational relationships play a crucial role in facilitating care preparation, as they often involve children’s commitment to providing care for their aging parents. Greater emotional closeness in the parent–child relationship can lead to more thorough preparation for future care [19], influencing both the decision-making process and expected outcomes regarding dyadic caregiving [29, 30]. Aging parents who regularly receive support from their adult children are more likely to recognize and prepare for their late-life care needs [31]. In addition, strong intergenerational ties can aid in the transfer of digital skills and knowledge, which are increasingly vital for effective eldercare planning. As older adults navigate the complexities of aging, support from younger generations in enhancing digital literacy empowers them to access resources, communicate effectively, and make informed decisions about their care.

2.2. Digital Literacy Contributes to Intergenerational Relationships and Future Care Preparation

The intergenerational solidarity model is relevant for studying the relationship between communication technology and intergenerational relationships. Younger generations often facilitate older adults’ adoption of the Internet [32]. Digital solidarity, as a new dimension of intergenerational solidarity, reflects the impacts of digital technologies and support provision. Digital technologies enable the provision of expressive forms of support [33] and may result in changes in personal communication and helping behaviors within intergenerational relationships [34].

Digital literacy is a valuable resource that can facilitate preparation for future care [35, 36]. Older adults view modern technology as essential for avoiding social isolation [37] and connecting with younger generations [38]. It enables older adults to interact more frequently with their family members and maintain these connections [39]. Social networking sites, in particular, help older adults to stay connected with distant relatives [40]. Older adults recognize the role of technology in maintaining independence, accessing information, and promoting health and wellness [38]. Therefore, digital literacy is crucial for proactive coping and preparation.

2.3. Gender Differences in Intergenerational Relationships, Digital Literacy, and Future Care Preparation

The gender of adult children can influence intergenerational relationships. Furthermore, the gender composition of a family may influence an older parent’s digital literacy and future care preparation. In both Western and Chinese cultures, daughters typically maintain more frequent daily contact with their parents than sons do [41, 42]. Older adults are more likely to receive care from daughters than from sons or expect such care [3, 43, 44]. The probability of receiving care from a son is less than half that of receiving care from a daughter. Moreover, sons with one or more sisters are even less likely to provide care and support [43].

With regard to digital literacy, older men are more likely than older women to use digital technology. Additionally, older men tend to possess higher levels of technical knowledge and skills than older women [45, 46]. Older adults lacking digital resources often turn to their families, particularly their children, for informal support [47]. However, it remains unclear whether the gender of adult children influences their parents’ digital literacy, the parent–child relationship, or future care preparation.

2.4. Theoretical Framework, Research Objectives, and Hypotheses

-

H1: Aging parents’ digital literacy is positively associated with their future care preparation.

-

H2: Aging parents’ digital literacy is positively associated with intergenerational relationship quality.

-

H3: Intergenerational relationship quality is positively associated with aging parents’ future care preparation.

-

H4: Aging parents’ digital literacy is influenced by the gender composition of their adult children: Older parents in son-dominant families have a higher level of digital literacy than do those in daughter-dominant or gender-balanced families.

-

H5: Intergenerational relationships are influenced by the gender of their adult children: Aging parents in daughter-dominant families have higher relationships with their children and are better prepared for future care than are those in son-dominant or gender-balanced families.

-

H6: The gender of adult children influences the mediating path: The influence of digital literacy on future care preparation through intergenerational relationship quality is stronger in son-dominant families than in daughter-dominant and gender-balanced families.

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Design

Data were obtained from the baseline wave of the Panel Study of Active Ageing and Society (PAAS). PAAS led by the first author is designed as a biennial representative panel study of adults aged 50 and over residing in Hong Kong [48]. Data in the baseline wave were collected between June and November 2022 from individuals aged 50 years and older who lived in Hong Kong, could speak Cantonese, and were cognitively capable of completing the questionnaire. Participants were selected through a random dialing method using landline and mobile phone numbers. The phone numbering plan of the Office of the Communications Authority of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region was used to initiate random phone calls for 26,000 landline and mobile phone numbers. After excluding invalid and nonresponsive phone numbers, PAAS successfully reached a total of 8,303 valid phone numbers. In each household, one eligible participant was selected by the “next birthday” method. The respondents were equally stratified into two age groups: 50–64 and 65 and over. The proportion of each stratum was determined based on the Population Census data in 2021 [49].

3.2. Data Collection

Structured questionnaire interviews were conducted by telephone by trained professional interviewers. The questionnaire was operated through a Web-based Computer Assisted Telephone Interview (Web-CATI) system, and the interviews were closely supervised. Interviews took approximately 30 minutes. Oral informed consent was obtained from each participant at the start of each interview. Ethics approval of the study was obtained from the first author’s affiliated university. Participants who failed to make contact, who declined participation due to time constraints or disinterest, and who did not meet study criteria were excluded. In total, 5007 of 8303 cases completed the interviews, resulting in a response rate of 60.3% [48]. A final sample of 3626 participants who had at least one adult child was included for analysis in this study.

3.3. Measurement

3.3.1. Intergenerational Relationship Quality

Intergenerational relationship quality was assessed using a scale adapted from the IRQS-AP [28]. IRQS-AP integrates the solidarity, ambivalence, and conflict models to assess the quality of relationships between older adults and their children in four domains, namely structural–associational solidarity, consensual–normative solidarity, affectual closeness, and intergenerational conflict. The scale employed contained five items, which were rated on a 5-point Likert scale. Structural–associational solidarity was assessed in accordance with the frequency of the participants’ face-to-face contact and communication with their adult children by phone, mail, or email, with endpoints for this item ranging from 1 (very seldom) to 5 (very often). Consensual–normative solidarity was assessed by asking whether the participants generally held similar opinions with their adult children, ranging from 1 (totally different) to 5 (totally the same). Affectual closeness was assessed by asking the participants to report their general feelings regarding the closeness of their relationships with their adult children, ranging from 1 (not close at all) to 5 (very close). Intergenerational conflict was assessed by determining the frequency of tension and strained feelings between the participants and their adult children, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always).

Participants were also asked to evaluate their general feelings regarding their relationship with their children, with answers ranging from 1 (very bad) to 5 (very good). Scores for the item that assessed intergenerational conflict were reverse coded, and total scores ranged from 5 to 25, with a higher score indicating a higher intergenerational relationship quality. The scale demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency in this study (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.63).

3.3.2. Future Care Preparation

The 5-item Chinese version of the Preparation for Future Care Needs Scale [10, 50] was adopted to assess preparation for their own future care. The scale comprised five critical domains: (1) awareness of future needs (“Talking to other people has made me think about whether I might need help or care in the future”), (2) gathering information about future care needs (“I have gathered information about options for care by talking to friends and/or relatives”), (3) making decisions about future care preferences (“If I ever need help or care, I can choose between several options that I have considered in some depth”), (4) concrete planning activities and plan initiation (“I have explained to someone close to me what my care preferences are”), and (5) avoidance of care planning (“I try not to think about things like future loss of independence”). The score for the avoidance-related item was reverse coded, and total scores ranged from 5 to 25, with a higher score indicating more preparation for future care. The scale demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.82) in this study.

3.3.3. Digital Literacy

Participants were asked to rate their digital literacy [51, 52] using a 5-point Likert scale item, ranging from 1 (not literate at all) to 5 (very literate).

3.3.4. Sociodemographics

Participant demographics were collected, specifically age, gender (0 = female; 1 = male), educational attainment (0 = junior high school and below; 1 = high school and above), family income, current marital status (0 = separated, widowed, or never married; 1 = married), living arrangement (0 = not live with adult children; 1 = live with adult children), and number and gender of their adult children. The participants were categorized into three groups in accordance with the gender composition of their families: daughter-dominant, son-dominant, and gender-balanced. A daughter-dominant family was defined as a family consisting of only daughters or having more daughters than sons, whereas a son-dominant family was defined as a family consisting of only sons or having more sons than daughters. A gender-balanced family was defined as a family with the same number of sons and daughters.

3.3.5. General Well-Being

The general well-being of an individual is indicated by the absence of depressive symptoms, good overall health, and sense of control over life [53]. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the 8-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale [54]. Total scores ranged from 0 to 24, with a lower score indicating a better mental health status. This scale demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.79). The participants self-rated their general health status using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (extremely bad) to 5 (extremely good). The participants self-rated their degree of control over their life (“In the past month, how often have you felt that you were unable to control important things in your life?”), using a 5-point Likert scale. These variables were treated as control variables.

3.3.6. Data Analyses

The raw data were weighted based on age, gender, year, and constituency area distribution with reference to the 2021 Census data in Hong Kong [55]. Unweighted data were used for subgroup analysis focusing on specific segments of the population. Correlation and regression analyses were used to test the association between the study variables (i.e., digital literacy, intergenerational relationship quality, and future care preparation) and sociodemographic characteristics.

A multigroup analysis using structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted to investigate the moderating effects of gender composition of adult children in the paths from digital literacy to care preparation through intergenerational relationship quality. This multigroup analysis approach allows for comparisons between different groups, distinguishing it apart from using SEM analysis alone. By developing multiple nested models—one to explore differences in relationships across groups and another to test the statistical significance of these variations—this method offers a comprehensive understanding of intergroup differences. Following the procedures suggested by Lutfi [56] and Alrawad et al. [57], this study developed two nested models. The unconstrained model served as the baseline for examining differences in relationships between variables across groups, while the constrained model imposed equal constraints on regression weights to determine the statistical significance of group differences [58]. By calculating chi-square (Δχ2) and degrees of freedom (Δdf) differences between the entire model and the constrained models, with constraints applied independently to specific paths, a detailed exploration of variations between different groups was achieved.

Mediation effects of intergenerational relationship quality on the relationship between digital literacy and future care preparation were investigated using the PROCESS Macro Model 4 [59]. This approach enabled testing the total effect (c), direct effect (c’), and indirect effect (ab) reflected by the standardized regression coefficients and significance levels between dependent and independent variables in each model. Bootstrapping was performed to compute the indirect effect for each of the 5000 bootstrapped samples and to obtain the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the indirect effect [60]. CIs that do not contain zero specify a significant indirect effect or mediation [61]. Data analyses were performed using SPSS version 27 [62] and Amos version 24 [63], and the significance level was set at p < 0.05.

4. Results

After the exclusion of participants who did not have an adult child or for whom the level of digital literacy was unknown (n = 1381), 3626 respondents aged between 50 and 95 years (M = 65.40, SD = 8.01) were included in this study, among whom 1983 (54.7%) were women. In total, 35.2% of the participants were from daughter-dominant families, and 36.6% were from son-dominant families. The remaining 28.3% were from families with a balanced number of daughters and sons. The majority of the participants (78.6%) were married, and 66.9% were living with their adult children. Furthermore, 40.3% of the participants had attained at least a high school education, and 36.1% had a single adult child. The mean scores for mental and physical health were 4.98 out of 24 and 3.22 out of 5, respectively. The mean scores for digital literacy, intergenerational relationship quality, and care preparation were 2.71, 18.28, and 13.98, respectively. Table 1 provides a summary of the participants’ characteristics.

| Characteristics | Adult child’s gender dominance group | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 3626) | Son-dominant (n = 1326) | Daughter-dominant (n = 1275) | Gender-balanced (n = 1025) | ||||||

| Mean | SD (%) | Mean | SD (%) | Mean | SD (%) | Mean | SD (%) | ||

| Age | 65.40 | 8.01 | 65.01 | 8.09 | 65.31 | 8.07 | 66.02 | 7.81 | |

| Gender | Male | 1643 | 45.30% | 640 | 49.00% | 525 | 41.20% | 468 | 45.70% |

| Female | 1983 | 54.70% | 676 | 51.00% | 750 | 58.80% | 557 | 54.30% | |

| Educational attainment | Junior high school and below | 2166 | 59.70% | 744 | 56.10% | 754 | 59.10% | 668 | 65.20% |

| High school and above | 1460 | 40.30% | 582 | 43.90% | 521 | 40.90% | 357 | 34.80% | |

| Living with adult children | Yes | 2425 | 66.90% | 879 | 66.30% | 824 | 64.60% | 722 | 70.40% |

| No | 1201 | 33.10% | 447 | 33.70% | 451 | 35.40% | 303 | 29.60% | |

| Marital status | Married | 2851 | 78.60% | 1053 | 79.40% | 960 | 75.30% | 838 | 81.80% |

| Separated, widowed, or never married | 775 | 21.40% | 273 | 20.60% | 315 | 24.70% | 187 | 18.20% | |

| Well-being | Mental health status | 4.98 | 3.54 | 4.88 | 3.46 | 5.26 | 3.75 | 5.92 | 3.59 |

| Physical health status | 3.22 | 0.80 | 3.26 | 0.80 | 3.20 | 0.80 | 3.20 | 0.77 | |

| Self-control rating | 1.92 | 0.88 | 1.89 | 0.86 | 2.01 | 0.91 | 1.86 | 0.84 | |

| Monthly family income (Hong Kong dollar) | 32,715.18 | 19,647.89 | 33,183.07 | 19,421.26 | 31,095.88 | 19,677.85 | 34,124.15 | 19,780.01 | |

| Number of adult children | 1 | 1309 | 36.10% | 719 | 54.20% | 590 | 46.30% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 2 | 1744 | 48.10% | 399 | 30.10% | 371 | 29.10% | 974 | 95.00% | |

| 3 | 461 | 12.70% | 199 | 15.00% | 262 | 20.50% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| 4 | 93 | 2.60% | 6 | 0.50% | 36 | 2.80% | 51 | 5.00% | |

| 5 | 19 | 0.50% | 3 | 0.20% | 16 | 1.30% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Digital literacy | 2.71 | 1.03 | 2.79 | 1.05 | 2.69 | 1.01 | 2.64 | 1.02 | |

| Intergenerational relationship quality | 18.28 | 2.79 | 18.02 | 2.77 | 18.64 | 2.88 | 18.17 | 2.63 | |

| Future care preparation | 13.98 | 4.12 | 14.07 | 4.11 | 14.50 | 3.87 | 13.24 | 4.32 | |

Differences in mean digital literacy, intergenerational relationship quality, and future care preparation scores between the three groups were examined using analysis of variance. The mean scores for digital literacy (F (2, 3623) = 6.868), intergenerational relationship quality (F (2, 3623) = 17.360), and care preparation (F (2, 3623) = 27.335) were significantly different between the three groups. Turkey’s post hoc tests showed that the participants in son-dominant families had higher average digital literacy scores than those in daughter-dominant families (Mdifference = 0.099) or gender-balanced families (Mdifference = 0.153). Participants in daughter-dominant families had higher intergenerational relationship quality scores than participants in son-dominant families (Mdifference = 0.621) and gender-balanced families (Mdifference = 0.465). Similarly, participants in daughter-dominant families had higher scores for future care preparation than those in son-dominant families (Mdifference = 0.433) and gender-balanced families (Mdifference = 1.259).

Table 2 shows the zero-order correlations between digital literacy, intergenerational relationship quality, and care preparation. Digital literacy was significantly but not strongly associated with intergenerational relationship quality (r = 0.231) and care preparation (r = 0.166). Intergenerational relationship quality was significantly and positively correlated with future care preparation (r = 0.149). The mediating effect of intergenerational relationship quality between digital literacy and future care preparation was further examined, while controlling for the covariates, in the entire sample and the three subgroups.

| DL | IRQ | FCP | Age | Gender | Edu | MFI | LA | MS | MH | NAC | PH | SC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DL | 1 | ||||||||||||

| IRQ | 0.231 ∗∗ | 1 | |||||||||||

| FCP | 0.166 ∗∗ | 0.149 ∗∗ | 1 | ||||||||||

| Age | −0.432 ∗∗ | −0.175 ∗∗ | −0.033 | 1 | |||||||||

| Gender | 0.124 ∗∗ | −0.103 ∗∗ | −0.041 | 0.045 ∗ | 1 | ||||||||

| Edu | 0.361 ∗∗ | 0.138 ∗∗ | 0.142 ∗∗ | −0.371 ∗∗ | 0.077 ∗∗ | 1 | |||||||

| MFI | 0.270 ∗∗ | 0.201 ∗∗ | −0.010 | −0.310 ∗∗ | 0.035 | 0.251 ∗∗ | 1 | ||||||

| LA | 0.068 ∗∗ | 0.209 ∗∗ | −0.106 ∗∗ | −0.213 ∗∗ | −0.014 | 0.095 ∗∗ | 0.498 ∗∗ | 1 | |||||

| MS | 0.153 ∗∗ | 0.123 ∗∗ | −0.043 | −0.236 ∗∗ | 0.160 ∗∗ | 0.137 ∗∗ | 0.175 ∗∗ | 0.082 ∗∗ | 1 | ||||

| MH | −0.067 ∗∗ | −0.238 ∗∗ | 0.239 ∗∗ | 0.088 ∗∗ | −0.066 ∗∗ | −0.081 ∗∗ | −0.155 ∗∗ | −0.046 ∗ | −0.184 ∗ | 1 | |||

| NAC | −0.183 ∗∗ | −0.069 ∗∗ | −0.032 | 0.276 ∗∗ | −0.028 | −0.238 ∗∗ | −0.062 ∗∗ | −0.036 | −0.049 ∗ | 0.050 ∗ | 1 | ||

| PH | 0.336 ∗∗ | 0.244 ∗∗ | 0.095 ∗∗ | −0.281 ∗∗ | 0.044 ∗ | 0.196 ∗∗ | 0.156 ∗∗ | 0.052 ∗ | 0.129 ∗ | −0.288 ∗∗ | −0.165 ∗∗ | 1 | |

| SC | −0.102 ∗∗ | −0.158 ∗∗ | 0.178 ∗∗ | 0.126 ∗∗ | −0.062 ∗∗ | −0.031 | −0.074 ∗∗ | −0.060 ∗∗ | −0.120 ∗ | 0.370 ∗∗ | 0.062 ∗∗ | −0.209 ∗∗ | 1 |

- Note: Gender (coded 0 = female; 1 = male), Edu = educational attainment (0 = junior high school and below; 1 = high school and above), LA = living arrangement (0 = not living with adult children; 1 = living with adult children), MS = marital status (0 = separated, widowed, or never married; 1 = married).

- Abbreviations: DL = digital literacy, FCP = future care preparation, IRQ = intergenerational relationship quality, MFI = monthly family income, MH = mental health status, NAC = number of adult children, PH = physical health, SC = self-control.

- ∗p < 0.01.

- ∗∗p < 0.001.

4.1. Family Gender Composition Group Differences

The unconstrained entire model had a good overall fit, with all indices exceeding the recommended thresholds: χ2 = 585.629, df = 132, χ2/df = 4.437, p = 0.000, goodness-of-fit index (GFI = 0.986), adjusted GFI (AGFI = 0.971), comparative fit index (CFI = 0.982), normed fit index (NFI = 0.977), and root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA = 0.022). Furthermore, Table 3 presents the results of path coefficients and chi-square test results from the multigroup analysis, showing the relationships between variables in the models for the three different sample groups, as well as the entire sample, while accounting for the varying gender compositions of adult children. Significant differences were found between the constrained and unconstrained models (Δχ2 = 25.911, df = 9, p < 0.05), indicating that the relationships between variables varied significantly across families with different gender compositions.

| Relation | Entire sample | Daughter-dominant | Son-dominant | Daughter and son balanced | Δχ2 | Δ df | p | ΔCFI | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | CI | β | SE | t | CI | β | SE | t | CI | β | SE | t | CI | |||||

| DL - > IRQ | 0.168 | 0.049 | 9.275∗∗∗ | [0.360, 0.553] | 0.146 | 0.084 | 4.969∗∗∗ | [0.253, 0.583] | 0.155 | 0.081 | 5.042∗∗∗ | [0.251, 0.570] | 0.213 | 0.088 | 6.212∗∗∗ | [0.375, 0.721] | 2.089 | 3 | 0.554 | 0.000 |

| IRQ - > FCP | 0.204 | 0.025 | 12.272∗∗∗ | [0.253, 0.349] | 0.187 | 0.040 | 6.262∗∗∗ | [0.173, 0.330] | 0.195 | 0.041 | 7.124∗∗∗ | [0.209, 0.368] | 0.198 | 0.049 | 6.591∗∗∗ | [0.229, 0.423] | 9.902 | 3 | 0.019 | 0.000 |

| DL - > FCP | 0.103 | 0.074 | 5.642∗∗∗ | [0.271, 0.559] | 0.070 | 0.121 | 2.224∗ | [0.032, 0.507] | 0.107 | 0.121 | 3.469∗∗ | [0.182, 0.655] | 0.147 | 0.141 | 4.391∗∗∗ | [0.344, 0.899] | 6.733 | 3 | 0.081 | 0.000 |

- Abbreviations: DL = digital literacy, FCP = future care preparation, IRQ = intergenerational relationship quality.

- ∗p < 0.05.

- ∗∗p < 0.01.

- ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

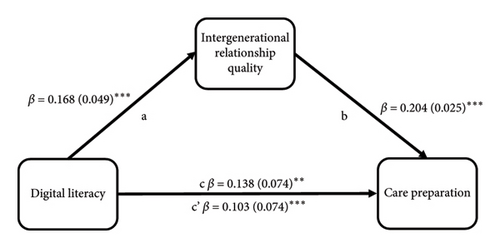

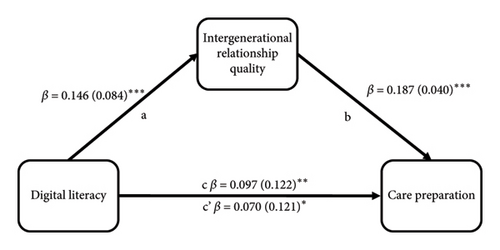

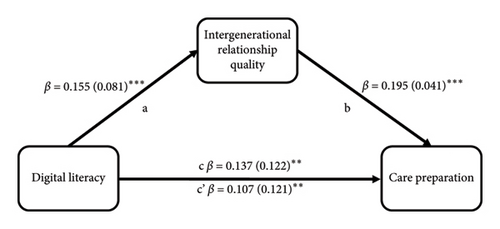

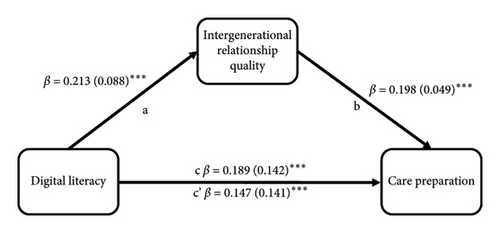

4.2. Mediating Effect of Intergenerational Relationship Quality

The path coefficients derived from the mediating effect of intergenerational relationship quality on the influence of digital literacy on future care preparation are shown in Figure 2. Digital literacy was significantly associated with intergenerational relationship quality (a-path) in the entire sample and the three subgroups (p < 0.001). Intergenerational relationship quality also exhibited a positive correlation with future care preparation, independent of digital literacy (b-path), in the entire sample and the three subgroups (p < 0.001). After incorporating the mediator (intergenerational relationship quality) into the models, digital literacy remained significantly associated with care preparation (c’-path) in the entire sample (p < 0.001), as well as in the daughter-dominant (p < 0.05), son-dominant (p < 0.01), and gender-balanced subgroups (p < 0.001). The magnitude of the association between digital literacy and care preparation, with the mediator of intergenerational relationship quality, decreased in the entire sample, the daughter-dominant group, the son-dominant group, and the gender-balanced group, indicating a partial mediation effect.

Results of the PROCESS Macro Model 4 analyses revealed a positive association of digital literacy and future care preparation, with complementary partial mediation by intergenerational relationship quality. The direct effects (c’-path) of digital literacy on future care preparation were significant in all three subgroups. Furthermore, the results of the indirect effect of digital literacy on future care preparation through intergenerational relationship quality (ab-path), using bootstrapping, were significant for the entire sample and all three subgroups. These results indicated that a portion of the effect of digital literacy on future care preparation is mediated through intergenerational relationship, while the digital literacy of older adults still explains a portion of future care preparation that is independent of intergenerational relationship. Moreover, digital literacy together with intergenerational relationship quality accounted for 14.5% (R2 = 0.145, p < 0.001), 10.1% (R2 = 0.101, p < 0.001), 15.5% (R2 = 0.155, p < 0.001), and 21.0% (R2 = 0.210, p < 0.001) variance for care preparation in the entire sample and the daughter-dominant, son-dominant, and gender-balanced subgroups, respectively.

5. Discussion

This study examined the relationships between aging parents’ digital literacy, intergenerational relationships, and future care preparation, as well as the influence of family gender composition. Consistent with our hypotheses, participants from son-dominant families exhibited the highest levels of digital literacy, whereas those from daughter-dominant families showed the highest levels of intergenerational relationship quality and future care preparation. Digital literacy was directly and indirectly related to future care preparation through intergenerational relationships. Participants with an equal number of daughters and sons benefited most from digital literacy’s influence on future care preparation.

These insights can inform policies and interventions aimed at enhancing digital literacy and strengthening intergenerational relationships, thereby improving the preparation for future care among aging parents. The moderate level of digital literacy may reflect Hong Kong’s efforts toward digital inclusion [64]. The mean item score reported for the short Preparation for Future Care Needs scale was 2.80, aligning with another Hong Kong study [10], but lower than the score reported in a U.S. study (2.93) [65]. This difference may attributed due to the sociocultural values of Chinese societies, which often discourage older adults from focusing on future care preparation and encourage reliance on family for future care [15]. Furthermore, the mean score of 3.7 for intergenerational relationship quality was moderately positive, possibly reflecting the Chinese traditional cultural value of filial piety, which emphasizes the importance of respecting seniors and ancestors [66].

The results supported H1, suggesting that digitally literate aging adults are more prepared for their future care needs. Older adults with greater resources are more likely to anticipate and engage in proactive coping with future stressors [67]. Technology aids older adults in proactive planning by providing access to information and resources to cope with challenges. Effective future care planning strongly depends on family members’ cooperation, knowledge, and participation [68]. Digital literacy enhances older adults’ access to family support, thereby facilitating future care preparation.

This study, conducted during COVID-19 restrictions, found a positive correlation between digital literacy and intergenerational relationship quality, supporting H2. The restrictions may have increased the participants’ use of technology. Digital literacy thus may have played a role in enhancing intergenerational relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic, enabling expressive communication by virtue of the immediacy of electronic contact between older adults and their adult children, and strengthening cooperative relationships [9, 69, 70]. Trusting relationships could be cultivated through online communication and support from adult children during the pandemic [71]. Therefore, the use of digital communication technologies, driven by social restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, may have heightened older adults’ digital awareness and reliance, thereby influencing the quality of intergenerational relationships.

Quality intergenerational relationships were associated with future care preparation, supporting H3. Older adults who have closer and more supportive relationships are more likely to engage in health-enhancing behaviors and experience better health [72–74]. This is attributed to social support from meaningful relationships and social control from significant others, which encourage health-enhancing behaviors. Aging adults are highly motivated to stay healthy for the benefit of their loved ones or may have better health due to the emotional and social support they receive from their family and friends [75]. By contrast, social control perspectives focus on the role of significant others in regulating an older adult’s health behaviors [76]. Loved ones, such as spouses and adult children, may directly encourage or persuade each other to engage in positive health behaviors, which can ultimately improve health and well-being [72]. Our findings suggest that a strong parent–child relationship can positively influence older adults’ awareness of healthcare and motivate them to prepare for future care.

Consistent with H4 and previous research, this study found that family gender composition affects aging adults’ digital literacy and older parents in son-dominant families are more digitally literate [77]. Adult children play a crucial role in assisting parents with technology by purchasing devices and installing equipment [78, 79]. Gender differences in digital propensity and self-efficacy regarding technology use also influence older adults’ digital literacy, with women generally having lower self-efficacy than men [80, 81]. These results suggest that adult sons are generally more confident in their ability to learn and teach technology compared with adult daughters, thereby enhancing their parents’ digital engagement.

The results support H5, suggesting that aging parents in daughter-dominant families have higher-quality intergenerational relationships and better future care preparation. Daughters, often primary caregivers, tend to have a stronger emotional attachment to their families and provide more emotional support to their older parents, while sons typically play a more substantial role in decision-making [82, 83]. These findings suggest that daughters may be more likely than sons to guide their parents in healthcare planning and encourage proactive health maintenance.

The results did not support H6. The finding showed that the direct and indirect effects of digital literacy were stronger in gender-balanced families than in son-dominant and daughter-dominant families. This could be explained by the fact that a mix of sons and daughters can address future care needs through traditional gender roles [84]. Sons are more equiped to provide technical and financial assistance, while daughters are typically more adept at offering hands-on caregiving and emotional support [85–87]. However, the influence of familial gender composition on the association between intergenerational relationship quality and care preparation is relatively weak. This may be due to the growing socioeconomic influence of Chinese adult daughters, who may provide more support than sons, particularly when they are married and living with their parents [88].

Demographic changes, such as lower fertility rates and smaller households in Hong Kong [89], may alter the role of adult daughters in future care support. With fewer children, parents can invest more in each child’s education and resources, creating stronger incentives for both daughters and sons to support their parents in old age [90]. This increased parental investment and reduced family size enhance the likelihood of adult children, regardless of gender, providing care for their aging parents.

6. Implications

This study underscores the significance of digital literacy in shaping intergenerational relationships and future care preparation. It aligns with Hong Kong’s recent policy to support older adults’ “age in place” through the service expansion of district elderly community centers and neighborhood elderly centers to include later-life planning [91]. The government and care service providers should consider incorporating future care preparation as a core component of retirement and later-life planning. Encouraging older adults to plan for their future care needs can mitigate potential threats to late-life well-being and provide more resources and options to handle adverse situations, reducing the associated stress [92]. Community education efforts should focus on developing social awareness of later-life planning, emphasizing the benefits of care preparation, and leveraging technology to facilitate this process.

Between mid-2019 and mid-2022, Hong Kong saw a population decrease of 0.99% due to the emigration of 219,000 residents [89]. The proportion of individuals aged between 20 and 49 years also dropped from 44.2% in 2016 to 41.4% in 2021 [93]. Many older adults chose not to emigrate with their children [94]. Digital literacy can help these older adults maintain long-distance relationships with their children and plan for future care. Through technology, older parents can receive social and emotional support from their adult children. The government can promote digital literacy by funding nonprofit organizations that provide activities and training programs, encouraging older adults to pursue and upgrade their digital skills. Gerontology practitioners should develop simple and age-friendly technological platforms, such as mobile applications and online platforms, to facilitate intergenerational care planningand manage future care plans and medication data.

In Hong Kong, 65.9% of individuals aged 65 or older had used the Internet in the preceding 12 months [95]. The Office of the Government Chief Information Officer (OGCIO) has implemented measures to help older adults understand and use technology [96]. This study suggests that these measures could be enhanced. For example, the Elderly IT Learning Portal, a Web-based learning portal maintained by the OGCIO, could include future care preparation and digital communication in their learning modules. Future care preparation is a dynamic process. For older adults with children and grandchildren, care preparation involves intergenerational planning for care location, provider, and type [10]. Planning for future care needs often involves addressing a range of medical, social, and psychological issues [50]. The promotion of future care preparation should be a collaborative effort by government agencies, such as Hospital Authority, Social Welfare Department, and health and community centers to ensure that older adults receive appropriate care and support for maintaining their health and well-being. Additionally, the influence of family gender composition on the digital literacy of older adults and intergenerational relationship quality reveals the different roles that daughters and sons play in motivating older adults’ engagement in future care preparation. Therefore, future care preparation training programs should not only be tailored for older individuals with varying intergenerational relationship quality and future care preparation levels but also be paired with digital literacy training.

The findings of this study also have significant implications for other societies in the Confucian Asia cluster, where family solidarity and filial piety are emphasized. These cultural values may enhance the willingness of adult children to engage in their parents’ digital literacy development and intergenerational preparation for their parents’ future care needs. The observed high-level intergenerational relationship quality in daughter-dominant families, along with the significant role of sons in promoting digital literacy among aging parents, reflects traditional expectations of adult children as supporters and protectors within the aging family. These cultural dynamics suggest that interventions aimed at improving digital literacy and care preparedness among older adults in these societies should leverage family roles and responsibilities. By aligning strategies with Confucian principles, policymakers, and service providers can more effectively engage families in supporting the aging population, ensuring that cultural values are respected while addressing contemporary and future care needs and challenges.

7. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits the ability to establish causal relationships between variables. While the path diagrams support postulated causal relationships, time series or longitudinal data are required to confirm the directionality of these relationships, particularly in the context of digital literacy–intergenerational relationship quality. For example, it is possible that adult children with more positive relationships with their parents spend more time teaching their parents about digital tools.

Second, the participants were aging adults with children; results may not be generalizable to those without children. Older adults without children may be more vulnerable and in greater need of formal support and care than those with children. Effective future care preparation can be even more crucial for their quality of later life. This is a crucial area for future research.

Third, the data for this study were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the results may not be representative of less challenging periods. The social restrictions during the pandemic may have motivated older adults to use digital communication technologies more frequently. Future research is needed to understand how social barriers, such as geographical distance, affect intergenerational relationship quality and future care preparation.

8. Conclusion

This study is the first to examine the relationship between digital literacy, intergenerational relationships, and future care preparation among aging Chinese parents in Hong Kong. A key and novel finding is that digital literacy influences aging adults’ future care preparation both directly and indirectly through the quality of intergenerational relationships. This study also investigates the influence of family gender composition on future care preparation. In particular, the direct and indirect effects of digital literacy on future care preparation are stronger in gender-balanced families than in son-dominant and daughter-dominant families. The findings of this study accentuate the importance of digital literacy in older adults’ preparation for future care needs and highlight the significant role played by adult children. To ensure that older adults receive adequate informational and technical support to plan for their future care needs, government, service providers, and gerontology practitioners should provide sufficient resources and training for family members, caregivers, and older adults.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This study was funded by the ZeShan Foundation and Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for all the participants in this study. We would also like to extend our gratitude to Prof. Karen Glaser from King’s College London who has provided insightful suggestions for us to improve the manuscript.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The dataset will be available upon reasonable request.