Spiritual Care and Community Wellness: A Mixed-Methods Approach to Explore Chaplains’ Integration in Community Health Initiatives

Abstract

Religious organizations have influenced parts of the history of healthcare in the United States. Whether at the local faith community level or national religious bodies, faith communities and health systems have explored partnerships to connect health service delivery and promote population health in its complexity. The changes to health policy in the past decades have fueled how health systems dedicate financial and tangible resources to improving the health of their local communities. Hospitals also increasingly hire and employ chaplains–professional spiritual care providers with extensive graduate and clinical education. The present explanatory mixed-methods study explored the integration of these chaplains in their health systems’ community health and wellness initiatives. The findings highlight that chaplains’ activities focus on social connection and improving healthcare access and quality. Chaplains highlighted how they use their interpersonal skills to build rapport and trust with communities, which may provide an additional resource for health systems looking to expand their impact within the local community. That possibility, however, comes with caution as chaplaincy education will need to include population health if the profession considers these activities core to their arena of expertise.

1. Introduction

Jeff Levin, a scholar of religion and health, has observed that the long-standing and diverse partnerships between religious and healthcare organizations are frequently underappreciated [1]. In his overview of these relationships, Levin describes 10 points of intersection. The first point describes the important role of faith-based organizations in the development of the first hospital centuries ago [2]. This history was repeated in the United States where Christian and Jewish organizations played a major role in founding early hospitals [2]. Faith-based organizations continue to play a significant role in U.S. healthcare, operating an estimated 16% of all hospitals in 2019 [3].

Another point of intersection described by Levin is widespread congregation-based health promotion activities. For example, in 1969, Granger Westberg, a former hospital chaplain, developed Wholistic Health Centers; clinics in church basements staffed by physicians, nurses, and pastoral counselors [4]. In his later years, Westberg aided in the development of parish nursing programs; churches hired nurses to provide support for members who were recently hospitalized, to assist congregants by referring them to healthcare facilities when needed, and to lead health promotion activities for church members [5]. Faith community nursing, as the work is currently known, is an American Nursing Association nursing specialty [6].

While health promotion today is generally led by health departments and healthcare organizations, local congregations are still seen as significant resources for health promotion activities, especially in minority communities [7, 8]. Using data from a survey of over 1300 U.S. congregations, Wong and colleagues found that 23% provided some type of programming to support people with mental illness [9]. Congregations in predominantly African American neighborhoods were more likely to provide such programs. Other congregation-based health activities have focused on cardiovascular health [10], physical exercise and weight control [11], and cancer screening [12].

The Memphis model, a project begun in 2004, is an innovative example of a more intense partnership between a healthcare organization and local faith communities designed to improve population health [13]. It consisted of a partnership between 604 congregations and Methodist Le Bonheur Healthcare, a 7-hospital healthcare system in Memphis, Tennessee. Hospitalized patients from participating congregations, the Congregational Health Network (CHN), received a visit from a navigator who assessed needs and worked with a congregational liaison to arrange postdischarge services. Additional community caregiving included transportation, food, social support, and more provided by several hundred trained congregational and community volunteers. An evaluation study found that time-to-readmission for CHN patients for all diagnoses was significantly longer than that of matched controls; their gross mortality levels were roughly half that of non-CHN patients [14]. Efforts to replicate the Memphis model in North Carolina were initiated in 2012; that project became known as the North Carolina Way [13].

Another point of intersection mentioned by Levin is hospital chaplaincy programs [1]; they are currently offered in an estimated 77% of U.S. hospitals [3]. In the late 20th century, hospital chaplains were seen as professionals who lived in both the world of the faith community and the healthcare system. In 1987, chaplaincy leader Lawrence Holst wrote, “The hospital chaplain walks between two worlds: religion and medicine” [15]. In the 21st century, chaplains’ work has focused on care for individual patients and their families [16] and also on care for healthcare staff [17]. There have been a few exceptions to chaplains’ focus on spiritual care for individual patients and their families. These include the work of chaplain Ron Sunderland and colleagues who in the 1980s and 1990s worked with local congregations in the Houston area to create support teams for patients with HIV/AIDS [18, 19]. A more recent exception is M.I.C.A.H. Project HEAL, an effort led by the spiritual care program at Mt. Sinai Medical Center to educate congregation-based lay health educators [20].

While healthcare chaplaincy has mainly focused on care for individual patients and their families, healthcare organizations have recognized the need to address population health and community wellness and the social determinants of health that influence them. Major policy changes and initiatives have spurred these efforts further by requiring healthcare organizations to make significant investments in addressing social determinants of health (e.g., Affordable Care Act) [21–23]. Healthcare organizations in recent years have led many of the efforts aimed at improving population health.

Although Levin [1] included hospital chaplaincy programs as one of the intersections between religion and healthcare organizations, he did not discuss chaplains’ involvement in community wellness and population health initiatives. However, many chaplains have a concern for the systemic factors that affect health [24]. Considering those commitments, and anecdotal evidence of some spiritual care programs’ involvement in community wellness initiatives, we designed this exploratory study to examine any current involvement of chaplains and their spiritual care programs in their hospitals’ community wellness initiatives.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

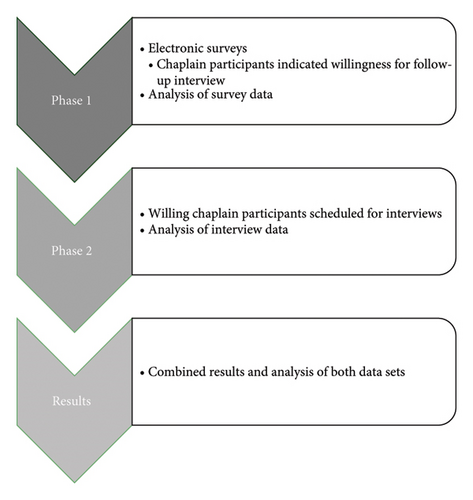

Given the lack of evidence about the extent to which chaplains support or lead population health initiatives, the research team utilized an explanatory sequential mixed-methods research design. The cross-sectional survey captured high-level input from chaplains to identify existing programs and their purpose. Follow-up interviews with survey respondents provided the opportunity for in-depth exploration. Figure 1 provides an overview of the phases of data collection for this study. Chaplains, often referred to as professional spiritual care providers, hold a master’s level education and often hold professional board certification. Furthermore, professional chaplains are trained to assess and intervene when individuals experience a crisis within their spiritual and/or existential identities regardless of faith identification (or none). The Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Virginia Commonwealth University deemed the present study exempt [IRB No. HM20025546].

2.2. Research Team Reflexivity

The research team consisted of three professional, board-certified chaplains (KW, PG, and GF) whose primary chaplaincy experience comes out of healthcare. Those same three authors are also trained with public health degrees (master’s and doctoral level). One team member works as a research assistant (KC) who holds bachelor’s level training in health policy analysis and management. Another team member (CS) is a Certified Educator by ACPE: The Standard for Spiritual Care & Education. Three team members identify as white males, one as a white female, and one as an African American female. Two team members have held previous positions managing and facilitating community wellness programs that integrated chaplains (CS and KW). The team member who conducted the interviews did not have any previous relationship with any of the chaplains who participated in the interviews.

2.3. Population and Recruitment

The research team invited chaplains who had participated in Transforming Chaplaincy’s Management Certificate Course, the wider community subscribed to Transforming Chaplaincy’s listserv, and chaplains within the Association of Professional Chaplains’ (APC) email distribution list to participants in an online survey. The invitation emails were distributed in April and June 2023. Approximately 5500 email addresses received our invitation, around 4800 opened the email, and 117 recipients clicked on the invitation. We did not calculate a response rate since we issued an invitation to a convenience sample of chaplains’ email addresses via email listservs.

A total of 46 chaplain respondents completed the survey. Of those respondents, two were removed due to working outside of the United States and one for working outside of healthcare. From the remaining 43, we removed 18 respondents who completed the survey but did not name any program that involved a chaplain. Thus, the final survey sample came to 25 chaplains. At the conclusion of the survey, chaplains were asked to indicate their willingness to participate in a follow-up interview (Phase 2). From the 25 chaplains who completed the survey, 21 (84.0%) were willing to participate in a follow-up interview with a member of the research team. Only 10 (40.0%) chaplains responded to email invitations to schedule an interview.

2.4. Data Collection

2.4.1. Survey Content

The research team developed a survey of 15 questions to gather these baseline data about chaplains’ integration into population health initiatives and programs. The survey, available in Appendix 1, included questions on the topics of (1) the employing organization’s characteristics; (2) the manager’s title; (3) the name, description, and level of chaplain involvement in community health initiatives; (4) if/how a chaplain supported activities at a federally qualified community health center (FQCHC), and (5) chaplains’ involvement with other social services provided by the hospital.

2.4.2. Survey Development

To ensure the content validity of the survey, the principal investigator discussed active initiatives with nine managers at hospitals—known through professional networks—that integrate chaplains within community health initiatives. These managers described their programs as well as the variability in their chaplains’ involvement. From their descriptions, we developed the survey as well as decided to include a definition of population health to ensure consistent interpretation of the question. The survey used an infographic format to define population health and ground their responses in a shared definition. The definition stated that population health is the “health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group” [25].

To address face validity, we pilot tested the survey by sending it to another group of managers also known through professional networks. The managers took the survey as well as provided feedback on the questions’ wording, content, and areas where they needed clarification. We then edited the survey for wider distribution. We collected survey responses between May 2023 and September 2023.

2.4.3. Interviews

Chaplain respondents who indicated their willingness to participate in a follow-up interview provided their contact information at the conclusion of the survey. The team aimed to gather in-depth stories and examples of how chaplains were integrated into their identified programs. One author (KW) conducted the semistructured interviews over a video conferencing platform between July 2023 and September 2023. Interviews lasted an average of 41 min and ranged from 26 (minimum) to 62 (maximum) minutes. They were audio recorded on the video conferencing platform and then transcribed by a third party. A copy of the interview guide is available in Appendix 2.

2.4.4. Analysis

Analysis within this explanatory mixed-methods study began with a descriptive analysis of survey results; the team aggregated the survey data at both the chaplain level and program level. The 25 chaplains who completed the survey named 84 programs that involved chaplains. During the descriptive analysis, programs were inductively categorized (based on the descriptions provided) according to (1) program/intervention type, (2) the targeted health need (physical, mental, or social), and (3) the level of chaplain involvement. Thirteen (15.5%) of the 84 programs were too vaguely named to categorize and thus removed from the analysis; this left the sample of programs at 71. We utilized the qualitative data to inform and build on the findings of the quantitative data and exemplify the ways chaplains were involved and the types of programs.

The team used the transcripts of the interviews to extract more information about chaplains’ descriptions of programs and inform the creation of the categories. Specifically, the team employed a sequential integration approach [26] when moving from the survey responses to the interviews. Ideally, those follow-up interviews would occur with a deliberate sample of survey respondents [27]; however, our small sample led the team to invite all willing chaplain survey respondents, who identified a program in which they were involved, to be interviewed. Deductive content analysis techniques [28] informed the categorization of programs as named above. The research team recognized that chaplains were highly focused on social determinants of health and so the team also categorized both survey content and interview transcripts according to the 2030 Healthy People domains [29]. Results with a reflexive thematic analysis, where we used an inductive approach [30], are available elsewhere [31]. Microsoft Excel and Stata SE 16 were used for quantitative analysis and AtlasTi for the qualitative analysis.

3. Results

Overall, the 25 chaplains who participated in the survey reported being involved in 71 programs that promoted community health and wellness; the 10 chaplains who participated in the interviews reported involvement with 37. Within the whole sample, chaplain respondents reported leading 38 (50.0%) of the programs, and among those we interviewed, they reported leading 21 of the 37 discussed programs (56.8%). Table 1 reports the demographic profile of the chaplain respondents, and Table 2 provides details regarding program characteristics.

| Characteristic | Survey-only sample N (%) | Interview sample N (%) | Total N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (% of total) | 15 (60.0) | 10 (40.0) | 25 (100.0) |

| Title | |||

| Director of spiritual care | 5 (33.3) | 2 (20.0) | 7 (28.0) |

| Spiritual care manager | 6 (40.0) | 4 (40.0) | 10 (40.0) |

| Senior director/vice president/regional manager | 3 (20.0) | 1 (10.0) | 4 (16.0) |

| Other | 1 (6.7) | 3 (30.0) | 4 (16.0) |

| Employing organization type | |||

| Health system | 8 (53.3) | 3 (30.0) | 11 (44.0) |

| Hospital | 6 (40.0) | 5 (50.0) | 11 (44.0) |

| Other healthcare | 1 (6.7) | 2 (20.0) | 3 (12.0) |

| Perceived organizational faith affiliationa | |||

| Catholic | 2 (13.3) | 2 (20.0) | 4 (16.0) |

| None | 6 (40.0) | 3 (30.0) | 9 (36.0) |

| Protestant | 7 (46.7) | 5 (50.0) | 12 (48.0) |

| Census region location | |||

| Midwest | 3 (20.0) | 3 (30.0) | 6 (24.0) |

| Northeast | 2 (13.3) | 2 (8.0) | |

| South | 8 (53.3) | 4 (40.0) | 12 (48.0) |

| West | 2 (13.3) | 3 (30.0) | 5 (20.0) |

| Works for multistate health system | |||

| Yes | 2 (13.3) | 4 (40.0) | 6 (24.0) |

| No | 13 (86.7) | 6 (60.0) | 19 (76.0) |

| Federally qualified community health center | |||

| Does not operate | 9 (60.0) | 5 (50.0) | 14 (56.0) |

| Operates without chaplaincy services | 1 (10.0) | 1 (4.0) | |

| Operates with chaplaincy services | 3 (20.0) | 2 (20.0) | 5 (20.0) |

| Unsure | 3 (20.0) | 2 (20.0) | 5 (20.0) |

- aThese are chaplain perceptions of their employing organization’s faith affiliation rather than formal ownership/control characteristics.

| Characteristic | Total N (%) |

|---|---|

| Programs by participant type | |

| Chaplain did not interview | 39 (51.3) |

| Chaplain interviewed | 37 (48.7) |

| Program type (n = 71) | |

| Health education | 28 (39.7) |

| Health system integration | 18 (24.7) |

| Bereavement/support group | 7 (9.6) |

| Community social networks | 5 (6.8) |

| Faith community nursing | 5 (6.8) |

| Community health needs assessment | 2 (2.7) |

| Other | 6 (9.6) |

| Social determinants of health (n = 75)a | |

| Healthcare access and quality | 46 (61.3) |

| Neighborhood and built environment | 1 (1.3) |

| Social and community context | 28 (37.3) |

| Target health need (n = 71) | |

| Physical health | 33 (46.5) |

| Mental health | 4 (5.6) |

| Social needs | |

| Social isolation | 16 (22.5) |

| Spiritual/existential and mental health | 10 (14.1) |

| Spiritual/existential health | 8 (11.3) |

| Chaplain role | |

| Actively involved | 38 (50.0) |

| Leads | 38 (50.0) |

- aCategories for the SDOH were defined based on the centers for disease control framework (CDC, N.D.).

3.1. Program Characteristics

Chaplain respondents named a total of 71 programs which averaged to 3.4 programs (SD = 2.3) per respondent; the range of total programs named by an individual was from 1 (minimum) to 8 (maximum). The largest proportion of the programs operated in the Midwest region (n = 17, 47.2%). The largest number of programs focused on health education (n = 29, 39.7%), followed by health system efforts to integrate chaplains/spiritual care within the community (e.g., mobile clinics; n = 18, 24.7%). Programs that provided support group-like interventions, that developed social resources for individuals, and that assessed community health needs were less common. Most of the programs discussed by the interviewees did not rely on a religious organization for operations nor partnered with a religious organization locally (n = 29, 80.5%). The majority of the programs that involved chaplains promoted healthcare access and quality (n = 26, 61.3%) as defined by the CDC’s framework for the social determinants of health. Programs that involved interventions (n = 38, 53.6%) focused on addressing mental and social needs over physical health needs. Although not asked within the survey, conversations with chaplain interviewees highlighted that most programs were of local and not national origins (77.1% to 22.9%, respectively). For example, local programs were designed for a specific context (see Tiffany’s programs) and programs with national origins were those, like parish nursing, were connected to programs designed elsewhere and expanded in other areas.

3.2. Unpacking the Survey Responses With Qualitative Exploration

To understand the program types and goals, we looked to the interviews for how chaplains elaborated on their activities. Specifically, we looked for explanations according to the most to least common type of program. Table 3 provides a joint display comparing the proportions of program intervention types and chaplains’ roles with an exemplifying quotation. Since population health efforts track their impact on health outcomes or outcomes of particular interest, we also wanted to consider chaplains’ descriptions of their programmatic impact. While very few chaplains were able to name measurable impacts of their programs, they were able to focus more on the social inequities that motivated their program(s)’ initiation. Without consistent approaches to consider programmatic impacts, we further looked to see what the chaplains reported about why they were selected to champion these efforts.

| Program type | Chaplain involvement level | Chaplain interviewee description | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Involved N (%) | Leads N (%) | Total N (%) | ||

| More common | ||||

| Health education | 16 (55.2) | 13 (44.8) | 29 (100.0) |

|

| Health system integration | 10 (55.6) | 8 (44.4) | 18 (100.0) |

|

| Common | ||||

| Bereavement/support groups | 1 (14.3) | 6 (85.7) | 7 (100.0) | “We spend half of one day in a small group setting discussing our opinions and thoughts about suicide. And we do it in a very non-threatening way. But you get people really thinking about, ‘Why is it hard for me to discuss this? What are my hang-ups?’” (David) |

| Less common | ||||

| Othera | 4 (57.1) | 3 (42.9) | 7 (100.0) | “With our community, we have a lot of people who have experienced scarcity in their life. And so a lot of them truly only come with their memories. And so this existential crisis was, ‘I’m losing those, I’m losing the last things that I have in my life.’ The priority was capturing memories in a book, in a tangible physical form.” (Tiffany) |

| Faith community nursing | 5 (100.0) | 5 (100.0) | “It started as Parish Nursing and I feel like that started maybe in [Pacific NW State], but we’ve had what was the Parish Nursing program, and now they’re calling it Faith Community Nursing, probably a little over 20 years, I think, here in [Pacific state]. What they do is, they do a lot of things, but they offer a training. Basically, the idea is to equip nurses who are part of churches or other faith communities to help be able to offer nursing ministry within the context of their churches. […] I’ve been involved with some of the training they’ve done around prayer and around appropriate spiritual care, recognizing that not everybody may believe exactly the thing that you do, even if they’re in your congregation, and helping them understand the difference between spirituality and religion, having healthy boundaries, knowing when to ask for help.” (Taylor) | |

| Community social networks | 1 (20.0) | 4 (80.0) | 5 (100.0) |

|

| Community health needs assessments | 2 (100.0) | 2 (100.0) | “So the three of us [the chaplain, a health system in a neighboring county, and the health department] would meet, the health department had the responsibility of getting a [Community Health Needs Assessment] questionnaire, a survey out to the entire community. Those results would come in and be tabulated. […] So I would have the responsibility of taking that information [the results of the Community Health Needs Assessment] and look, search for other resources as well to write the report for [Southern] Medical Center.” (Suzanne) | |

- aThose programs labeled “other” were put within the “less common category” due to each of their own individual characteristics. Even though the total number adds up to 7, they are not easily comparable to one another.

3.2.1. Patterns in Programmatic Strategies: Most to Least Common

The integration analysis of the survey data with the data collected from the interviews highlighted how some approaches were more common while others were less common. Table 3 provides a joint display of the programs with their descriptions from interviewed chaplains; it starts with the most commonly programs to the less common.

Chaplains most frequently described their participation in health fairs or educational workshops. Educational topics discussed through workshops or other workforce educational modalities included resilience, Advanced Care Planning, or how to provide spiritual and emotional care within the community. One chaplain (Ellis) explained that their educational program focused on the impact of trauma and the role of resilience. Advanced Care Planning also arose as topic frequently addressed by several chaplains.

Several chaplains described approaches to community bereavement support, support groups, and how their health system has integrated them into their existing programs by way of attending to spiritual distress. For instance, one chaplain (Reese) described that their health system used chaplains to identify patients struggling with social isolation. Reese spoke about developing an initiative that utilized chaplains, albeit for those hospitalized on an inpatient basis, to assess for challenges within the social determinants of health screener. Specifically, chaplains were to pay attention to social isolation of individuals. Other chaplains (Jane and Suzanne) discussed how chaplains provide follow-up support to recently discharged individuals to see if they are struggling to afford medications. Both Jane and Suzanne talked about their respective approaches to follow up with patients after their discharge. The chaplains would call to ask about how the individual had been doing since their hospitalization and within conversation, they would listen for struggles such as food insecurity and ability to pay for medication. If those conversations identified issues for the individual, the chaplain would highlight or connect them to resources that could alleviate the challenge(s).

Less common approaches included chaplain leadership within Faith Health Nursing programs and efforts to build community support networks for individuals who were at high risk for hospital readmission. Efforts to develop community support networks, as described by one interviewee, focused on reducing social isolation and connecting individuals to resources such as transportation or help with food insecurity.

We also interviewed chaplains who named programs that were developed for a very localized population. For example, one chaplain talked about aiding with a mobile clinic that provided health services to a local unhoused population who consistently showed up in local emergency rooms. Sean described how the spiritual care department occasionally supports a mobile clinic staffed completely by volunteers who provide medical care to a local unhoused population. Their team recognized the importance of meeting those seeking care where they were and connecting with local organizations that already had the trust of those seeking care.

The interviewee (Tiffany) who shared about the program for individuals with dementia also named a program that gave individuals with limited physical abilities opportunities to make kits, hats, or blankets for other nonprofit organizations in their community. In another example, Taylor described a chaplain-led initiative (unrelated to the hospital’s services) that focused on creating safe housing for youth who identify as LGBTQIA. Many of these localized and less common efforts developed as a product of chaplain-assessed need and chaplain-driven passion.

3.2.2. Discussing Programmatic Impact

“We [the chaplains] can’t take ultimate claim for this. Lots of people are doing lots of work, but patients [enrolled in this program] compared to control patients are about 4.5% less hospital readmissions, and impressive results in terms of ED utilization going down and medications and family practice visits going up, so the things you want to see, we’re having good trends on.” (Carrie)

“We have a dashboard in our population health and system health services, dashboards that we track monthly, and then our pre- and post- loneliness scales [that] consistently show statistically validated improvement [meaning] that people feel less lonely, feel more connected.” (Carrie)

“We started in January 2023 and what’s been happening, and this blew my mind… So last year the [organization]’s executive director sent me some statistics. Last year, they gave almost 50 bus tickets for the year-50 bus tickets to clients so they could come to our emergency room to be seen by a doctor. Now, this year, as of July, they gave 26 bus tickets, but it was for the clients to come to our hospital to get labs or imaging instead.” (Sean)

“An additional benefit, obviously, is that we’re trying to also prevent readmissions and ED visits as well, which most of these patients would have to do because they ran out of medication. […] So we’re trying to do multiple things with that program. And it works. We literally have the numbers about how many ED admissions and readmissions to the hospital we’ve reduced over time through the program.” (Jane)

“The [local] community was tapping into this whole boomer community that exists of people who are nearing retirement or are in retirement, that come with specific skillsets. And that specific skillset was in writing. And so I started advertising, was getting a writer of the regional newspaper to write an article on this story. […] We got this wonderful response from people who…Some were professional writers, a lot of them were hobbyists. We ended up with people as young as 30 and as old as 88.”

“This community of writers became a community in and of themselves […] and it really helped them. Many of them came wanting to assist people, particularly with memory issues, because somewhere in their life they had a loved one who struggled in the same way, or a loved one who was in a nursing home

[…]

[One writer] came from a town on the Russian-Ukrainian border and was writing when war broke out. […] She didn’t even know if she could do the book and her resident ended up dying in the process. But for her, she tells this beautiful story of how it shifted, for her, it was hope filled for her at a time when she was uncertain about loved ones and […] whether her family still existed back there.

[…]

We had four of our residents pass during this project. And it impacted families too in that books were presented to the family. And for them, that was absolutely priceless to have the words that their loved ones and the memories that they recalled. We also had bookcases out on the units … we made a very intentional effort of making the book accessible to staff.” (Tiffany)

“The one thing I wish that could be measured would be… I mean, I keep saying I think what we’re doing is impacting length of stay or it could, because when you have people who have their wishes clearly talked about ahead, then they’re not lingering trying to make those decisions, or lingering because we can’t reach [family or friends]. […] But I can’t prove that.” (Sandra)

“Well, certainly they [community members] have become a little bit more educated around what’s possible. They have been reportedly given voice and words that they can use to advocate on their own behalf. They now understand that there are people that they can go to or talk to, that they may or may not be your physician, that can get you to the support that you need.” (Ellis)

Regardless of measurable impact, almost all chaplain interviewees reported that interdisciplinary and community collaboration was key to the success of their programs.

3.2.3. Why Chaplains?

“I think the element of surprise works in our favor because they [community members] are not expecting the chaplain to be this patient advocate. And so, I think it disarms them sometimes. Because we also have rapport with the [clinical] staff, because we are providing spiritual care support to the staff as well, they are more likely to hear us.” (Ellis)

“A second part that’s […] deeply important right now, is the [chaplain’s] ability to have thoughtful and meaningful interfaith but theologically challenging conversations in a time in which political discourse and theological discourses in the public sphere are so very challenging. We [chaplains] are able to hold across those spaces. [Our state] has just passed a really complete, near-total abortion ban. We’ve just passed legislation here banning gender-affirming care. Those kinds of things are deeply difficulty for our providers, of course, and for many of our patients. I think the chaplain can move into those spaces and help hold conversations that are meaningful and rich.” (Carrie)

Chaplain interviewees shared their perceptions of their contributions and discussed the unique skillsets that they brought to these initiatives. Many considered their ability to build community rapport to be vital; similarly, important was utilizing existing relationships grounded in trust. In other words, chaplains first focused on building interpersonal relationships with community members to establish trust. Those built relationships enable them to develop new programs or expand the collaboration for existing programs.

3.2.4. FQCHCs

Finally, we asked chaplain respondents to identify whether or not their employing organization operated a FQCHC. Among the 25 chaplain survey respondents, 14 (56.0%) reported working for organizations that do not operate a FQCHC. Eleven chaplains reported working for organizations with a FQCHC, and of those 11, five respondents (20.0%) worked for an organization that operated a FQCHC that also integrated chaplaincy services within that center. When asked about the level of integration in those centers, chaplain respondents indicated that the availability of spiritual care ranged from “referral based” to “highly integral to the activities of the center and care to the staff.” Two noted providing care as requested and the other three reported typical chaplain activities (i.e., spiritual care visitation, weekly reflections for staff, employee support, and bereavement support) within the center.

4. Discussion

Healthcare organizations’ efforts to improve the health of their communities have grown in recent decades [23, 32]. The recognition that inequitable health outcomes arise from complex disparities within our social and built environments has fueled the development of innovative initiatives [33]. Historically, health systems have fostered relationships with local religious communities to aid in health promotion activities and more recently have tapped into the skillsets of professional chaplains to develop innovative programs and connect with community members [34]. The present study explored the ways in which chaplains are involved in community health and wellness initiatives with an explanatory mixed-methods approach. Survey results highlighted a range of initiatives where chaplains both participate in and lead the initiative. Follow-up interviews aided in describing how chaplains’ activities often target disparities within the social determinants of health rather than focus on achieving specific health outcomes. These activities primarily focused on healthcare access and quality and their local social and community context. Furthermore, many of the programs addressed health education. Chaplains may provide healthcare systems with unexpected resources to develop trust and relationships with local communities.

Our results provide the first attempt to look at how chaplains, across the United States, are involved in promoting community health and wellness. Chaplains’ attention to healthcare access and quality may be connected to the shifting attention in professional chaplaincy to outpatient and cross-continuum spiritual care provision [35]. The present findings may be connected to the expanding evidence of chaplains’ adapting clinical practice. For example, the growing number of chaplains utilizing telechaplaincy to provide spiritual care may lead to increased access to professional spiritual care as well as communities’ access to individuals who would refer an individual to formal medical/health care [36, 37].

Clinicians from all levels of healthcare delivery are shifting toward more quality and less siloed approaches to care. Additionally, evidence is growing that speaks to chaplains’ role in the experience of health system users [38–40]. The emphasis on the social and community context may originate from the long recognition by chaplains that social isolation and human connection impact health and wellbeing [41, 42]. For many decades, professional chaplaincy standards have included requirements that professional chaplains not only develop deep relationships with trust and sensitivity but also navigate group dynamics, how cultural identities can influence health decisions, and advocate for care receivers [43]. The increased recognition by our wider society that social isolation plays a significant role in health outcomes may have influenced this attention as well. Healthcare executives may be leaning more on chaplains for the increasing demands placed on health systems by policy and regulations due to their quick ability to attend to and integrate complex phenomena. Furthermore, wider society has begun to recognize the urgency of addressing social and access disparities. The recent advisory by the U.S. Surgeon General about social isolation offers one such instance of increased conversation regarding the implications of unaddressed health needs beyond the direct delivery of care [44]. That report suggests that the rapid expansion of technology alongside the crises we have faced as a world during the COVID-19 pandemic have exacerbated how lacking interpersonal support can have consequences for morbidity and mortality [45].

The frequent efforts of chaplains to focus on health education may have arisen due to chaplains’ frequent identification as “translators” between the world of the patient and health care [45, 46]. Health literacy includes the knowledge about health and health systems, how one processes the information as related to its format, and one’s ability to self-manage and self-advocate [47, 48]. Literature from inpatient encounters identifies the concrete impact chaplains make on caregivers’ communication with the hospital team and healthcare decision making [49] such that it would make logical sense chaplains would aim to extend those skills to the community. At the same juncture, health education interventions often lack the substantive impact for the community since barriers to health often arise from factors outside of individual control such as genetics or environmental circumstances [50]. Health education efforts most effectively impact communities when they target multiple levels of a community’s identity—educating the community through public campaigns, regulations around the cost of ignoring the health-promoting activity, and increasing the identification of resources/assets within the local area [51]. Future research should explore the effectiveness of chaplains’ health education efforts and if a range of message promotion matters.

Further challenging chaplains’ efforts is their understanding of the importance of data tracking/analysis. Existing research does suggest chaplains’ training with research and/or understanding the importance of data in quality improvement efforts is limited [52]. Since most chaplains receive education within theological schools [53] and separate from other public health professionals, their educational curricula lack addressing public health or social determinants of health [41, 54, 55]. The expectation for healthcare chaplains to cultivate relationships with local faith communities is not named as an explicit outcome within their clinical training [56]. This role or expectation is also not specifically identified within the APC 15 Standards of Practice for Professional Chaplains [43]. If professional chaplains want to continue using their skills to aid in improving social isolation, then professional chaplaincy organizations and educational institutions will need to address this gap.

Although our results suggest chaplains are involved in community health and wellness efforts, their integration appears minimal. Given professional chaplains’ interpersonal expertise and dedication to the psychosocial–spiritual wellbeing of those seeking healthcare services, one would expect health systems to depend more intentionally on chaplains. Limited use of chaplains in this manner could arise from a limited understanding by the wider public [41]. At the same juncture, health system administrators may have limited understanding of chaplains’ roles [57–60] which could further minimize their involvement.

4.1. Limitations

Even though the present study provides unique insights into chaplain’s involvements in community health, it comes with limitations. First, the study design may have introduced response bias as we invited chaplains rather than other hospital representatives to speak to chaplains’ involvement and identification of community health initiatives. Second, the small sample size and vague descriptions provided by chaplains limit our ability to generate generalizable results. The findings should be interpreted as observational rather than assumptive of all healthcare chaplains. Finally, although we aimed to minimize variations in responses by providing respondents with a shared definition of population health, we could not eliminate all discrepancies.

5. Conclusion

Achieving a healthier society and ensuring equitable health outcomes will require cross-sector collaboration and adapting resources. Some healthcare chaplains are providing leadership and innovation to aid in efforts to address inequities in the social determinants of health. Their integration in health system initiatives to improve community wellness has gone beyond providing religious-based support as traditionally assumed by many clinicians. These skills may prove beneficial to health systems looking to maximize the skills of their workforce beyond their walls. At the same juncture, chaplains must consider the nuances and additional educational paradigms that will introduce for their professional jurisdiction. Future research should consider what value chaplains bring—from the community perspective—to community wellness initiatives. Researchers will also want to explore how programs with and without chaplain leadership or involvement may differ in impact and functionality.

Conflicts of Interest

Kelsey White, Paul Galchutt, and George Fitchett are board-certified chaplains (BCC). Csaba Szilagyi is a certified educator by ACPE: The Standard for Spiritual Care & Education.

Funding

This work was supported by Transforming Chaplaincy at Rush University and conducted in partnership with Virginia Commonwealth University.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request due to privacy/ethical restrictions.