Interrelationships Between the Holistic Wellbeing Quadrants and Social Wellbeing of Older Persons in Ghana

Abstract

The global population is ageing at an unprecedented rate, with Africa experiencing the fastest growth in the number of older persons (aged 60 and above), followed by Latin America, the Caribbean and Asia. Like other developing nations, such as Zimbabwe, Namibia, India and Indonesia, Ghana is witnessing a rapid rise in its ageing population. It is crucial to understand and address the unique wellbeing needs of Ghanaian older persons. This study examined the interrelationships between emotional, physical, psychological and spiritual wellbeing and their collective influence on the social wellbeing of older persons in Ghana. Using data from the World Health Organization’s Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE) Wave 2, a sample of 1927 individuals aged 60 and above was analysed through structural equation modelling (SEM). Results reveal that physical wellbeing (β = 0.57, p < 0.001) strongly predicts social wellbeing, followed by spiritual (β = 0.25, p < 0.001), emotional (β = 0.17, p < 0.001) and psychological (β = 0.17, p < 0.001) wellbeing. In addition, each wellbeing dimension interacts synergistically, enhancing overall social wellbeing (integration, acceptance, coherence, contribution and actualisation). Factors such as sex, marital status and perceived health significantly mediate these relationships, with older females and married individuals reporting higher social wellbeing. The findings highlight the need for multidimensional interventions to support healthy ageing, advocating for policies that enhance the interconnected wellbeing dimensions to foster social inclusion and quality of life for older persons in Ghana. Holistic care models should be adopted for multidimensional care approaches addressing emotional, physical, psychological and spiritual wellbeing to enhance social wellbeing of older persons.

1. Introduction

The global population is ageing rapidly, with Africa leading in the growth rate of older persons (aged 60+), followed by Latin America, the Caribbean and Asia. Like other developing nations, such as Zimbabwe, Namibia, India and Indonesia, Ghana faces a swift increase in its older population [1]. Worldwide, the number of individuals aged 60 and above is projected to reach 1.4 billion by 2030 and double to 2.1 billion by 2050, marking a profound demographic shift [2]. In sub-Saharan Africa, this age group is expected to make up 8.3% of the population by 2050, while Ghana is forecasted to rise to about 11.9% [3].

Older persons are commonly classified into three age groups: young–old (60–69 years), who generally remain active with fewer health issues; old–old (70–79 years), who may experience increased age-related health concerns and shifting social roles and oldest–old (80+ years), who often face higher risks of cognitive decline, chronic conditions and require more assistance with daily activities [4]. Classifying older persons into the young–old (60–69), old–old (70–79) and oldest–old (80+) age groups highlights the need to understand the unique wellbeing challenges faced by each cohort. Investigating the interrelationships between holistic wellbeing quadrants—emotional, physical, psychological and spiritual—and social wellbeing is essential for healthy ageing in Ghana [5]. Each age group encounters distinct shifts in health, social roles and independence that affect their integration and participation in society.

Healthy ageing is increasingly recognised as a multidimensional concept, particularly in developing countries like Ghana, where the ageing population faces numerous social, economic and health challenges [6]. Healthy ageing goes beyond the absence of disease or disability, encompassing physical, emotional, psychological, spiritual and social wellbeing [7]. These dimensions of wellbeing work together to ensure that older persons maintain their autonomy, dignity and ability to contribute meaningfully to society [8]. Thus, we cannot overlook the relevance of this study subject.

The wellbeing of older persons, particularly in Ghana, encompasses multiple measurements that together shape their overall life satisfaction and quality of life [9]. These measurements include emotional, physical, psychological and spiritual wellbeing (holistic wellbeing quadrants), all of which are critical to how older individuals traverse the ageing process [9]. It is relevant to investigate the interrelationships between these domains of wellbeing because they are connected. However, information on how they interconnect to impact social wellbeing is generally limited. Emotional distress can contribute to physical ailments like cardiovascular disease, while spiritual wellbeing enhances psychological wellbeing [10]. Psychological stress weakens immune function, whereas emotional and spiritual wellbeing improves health outcomes, particularly for older persons with chronic illnesses [11, 12]. In addition, psychological wellbeing plays a crucial role in emotional regulation and stress resilience, with mind–body practices like mindfulness reducing anxiety and enhancing overall wellbeing [13]. Spirituality also fosters a sense of purpose and meaning, mitigating depression and anxiety while promoting improved emotional wellbeing [10, 14]. Understanding these interconnections is essential for a holistic approach to health and wellbeing.

The interrelationships between emotional, physical, psychological and spiritual wellbeing are supported by established theoretical frameworks. The self-determination theory [15] suggests that wellbeing is driven by autonomy, competence and relatedness, with emotional and spiritual factors enhancing motivation and resilience. Also, the biopsychosocial–spiritual model [16] extends Engel’s framework, emphasising spirituality’s role in health outcomes. Positive psychology [17] highlights flourishing through meaning, gratitude and mindfulness, which enhance wellbeing and physical health. The psychoneuroimmunology [18] further links emotional and psychological states to immune function, demonstrating how stress and wellbeing influence physical health. These models collectively show the need for an integrated, holistic approach to understanding wellbeing. Yet, the relationships between these domains and their impact on social wellbeing, a key factor influencing social integration, coherence, contribution, acceptance and actualisation of older persons, have not been explored extensively [8, 14].

An ageing population presents challenges that bring the issue of wellbeing into focus in Ghana [6, 7]. Older persons often face emotional stress, declining physical health and psychological challenges that stem from decreased independence, loss of social roles and spiritual concerns [8]. These factors affect their interactions with society and their sense of belonging. Social wellbeing, which includes their ability to integrate into social networks, contribute to their communities and feel accepted, coherent and actualised, also plays a crucial role in improving their overall quality of life [8, 14].

The holistic wellbeing quadrants have been widely recognised as a critical factor in promoting healthy ageing and improving the quality of life among older persons. Social wellbeing, which includes social integration, contribution, acceptance, coherence and actualisation, is deeply intertwined with these holistic wellbeing domains [19]. Emotional wellbeing refers to the ability to manage emotions, foster positive relationships and experience a sense of life satisfaction. Research highlights that emotional wellbeing plays a significant role in shaping the social wellbeing of older persons [20]. Individuals with greater emotional stability and higher life satisfaction are more likely to participate in social activities, maintain robust social networks, and feel a strong sense of belonging within their communities [21]. Conversely, emotional distress—such as feelings of loneliness or depression—can lead to social isolation and decreased involvement in community life [22]. Older persons often encounter emotional challenges, including the loss of loved ones, declining independence and changing family dynamics, all of which can hinder their social integration and overall wellbeing [23].

Physical wellbeing, which encompasses maintaining functional health and managing chronic conditions, is a cornerstone of healthy ageing. Studies have demonstrated that older persons with better physical health are more likely to engage in social activities, contribute to their communities and preserve their independence [24, 25]. Conversely, physical decline—such as mobility limitations or chronic illnesses—can hinder social interactions and contribute to feelings of isolation [26]. In contexts where access to healthcare and social support systems may be limited, physical wellbeing becomes even more critical in shaping older persons’ social engagement and overall quality of life [23].

Psychological wellbeing encompasses cognitive functioning, resilience and a sense of purpose in life. Evidence shows that older persons with higher psychological wellbeing are more likely to experience social coherence, acceptance, and actualisation [27]. Also, older persons who maintain a positive outlook and a sense of purpose are more likely to engage in meaningful social roles and contribute to their communities [28]. Conversely, psychological distress can hinder social interactions and reduce feelings of social acceptance [29]. Older persons often face psychological challenges due to economic hardships, loss of social roles and limited access to mental health services in Ghana, which can adversely influence their social wellbeing [30].

Spiritual wellbeing, which involves a sense of meaning, purpose and connection to something greater than oneself, is particularly significant in the context of ageing. Research suggests that spiritual wellbeing can enhance social wellbeing by fostering a sense of community, belonging and resilience in the face of life’s challenges [31]. Older persons who engage in spiritual practices, such as prayer or meditation, often report higher levels of social integration and life satisfaction [31]. Spirituality and religion in Ghana play a central role in daily life; spiritual wellbeing is a key factor in promoting social cohesion and emotional resilience among older persons [32].

Previous studies suggest that emotional and psychological wellbeing enhances physical health, reducing the risk of chronic illness and promoting longevity [33–35]. Likewise, spiritual wellbeing has been associated with lower stress, improved mental health and strengthened immune function [14]. Evidence supports mind–body interventions such as mindfulness and gratitude practices, which enhance emotional and spiritual wellbeing, reduce psychological distress and inflammation and, in turn, improve physical health [36, 37]. In addition, positive psychology research highlights that meaning and purpose in life foster psychological resilience and physical wellbeing [17].

However, some studies reveal trade-offs where prioritising one aspect of wellbeing may come at the expense of another. For instance, rigid exercise or dietary regimens, while beneficial for physical health, can sometimes induce psychological stress or social isolation. Similarly, deep spiritual engagement may provide emotional and psychological benefits, but in certain cases, it may conflict with evidence-based medical treatments, leading to negative physical health consequences [38].

Despite the growing body of literature on holistic wellbeing and social wellbeing, several gaps remain. First, most studies have examined these domains in isolation, often using regression analysis, which limits the understanding of their interconnectedness [1, 39, 40]. Second, there is a lack of research on these dynamics in developing countries, where older persons face unique social, economic and health challenges [39]. Third, few studies have employed robust methodologies, such as structural equation modelling (SEM), to examine the collective influence of holistic wellbeing domains on social wellbeing [41, 42]. Addressing these gaps is essential for developing comprehensive strategies to promote healthy ageing in diverse cultural contexts. Specifically, understanding how emotional, physical, psychological and spiritual wellbeing interact to shape social wellbeing is essential for developing comprehensive strategies to enhance the quality of life of older persons in Ghana. The study sought to answer the question: How do the interrelationships between emotional, physical, psychological and spiritual wellbeing domains influence social wellbeing among older persons aged 60 and above in Ghana? To address this, the study investigated how the interrelationships among the holistic wellbeing quadrants impact social wellbeing among older Ghanaians 60 and beyond, thereby contributing to a comprehensive understanding of healthy ageing. It recognises that enhancing these domains of wellbeing can improve social wellbeing and overall quality of life for older persons in Ghana. This fosters an inclusive society where older persons can age healthily, actively participate in their communities and experience a fulfilling and dignified life.

2. Materials and Methods

This study analysed data from Wave 2 (2014/15) of the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) Ghana Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE), which surveyed the health and wellbeing of older persons. SAGE, a longitudinal survey coordinated by WHO’s Multicountry Studies Unit, is conducted in six countries (China, Ghana, India, Mexico, Russia and South Africa) to gather data that inform policies addressing the needs of ageing populations [43]. Wave 2 of SAGE Ghana collected data on various aspects of older persons’ wellbeing, including emotional, physical, psychological, spiritual, social and sociodemographic information. Using a stratified two-stage sampling method, the survey sampled 214 primary sampling units (PSUs) from the 2010 Ghana Population and Housing Census. Within each PSU, households were selected through systematic random sampling, and all members aged 50 and above were interviewed. In total, 3575 respondents aged 50 and above were surveyed. For the analysis in this study, only participants aged 60 and above were included, resulting in a sample size of 1927. This study used the functional age brackets categorised as follows: 60–69 (young–old), 70–79 (old–old) and 80+ (oldest–old) [44, 45]. The data were selected for its national representativeness and cross-country comparability through standardised procedures, including sampling, questionnaire development, data cleaning and coding.

2.1. Variables

2.1.1. Outcome Variable

The primary outcome variable, the social wellbeing of older persons, was measured across five subdomains: social integration, social contribution, social acceptance, social coherence and social actualisation, based on items from the WHO (SAGE) Subjective Wellbeing Scale, Quality of Life Scale and the Social Cohesion Scale. Responses were rated on a 5-point Likert scale, from “never” to “very often” or “very dissatisfied” to “very satisfied.” To analyse predictors of the outcome variable, social integration, social contribution, social acceptance, social coherence and social actualisation were the observed variables, with higher scores indicating higher social wellbeing. The Subjective Wellbeing and Quality of Life scale has shown strong validity and reliability in past studies [33, 46, 47].

2.1.2. Independent Variables

The independent variables considered for the study were emotional, physical, psychological and spiritual wellbeing, based on items from the WHO (SAGE) Subjective Wellbeing Scale, Quality of Life Scale and the Social Cohesion Scale. Emotional wellbeing was measured by four factors: “How much of a problem did you have with feeling lonely?,” “How much of a problem did you have with worry or anxiety?,” “How much of a problem did you have with feeling neglected?” and “How much of a problem did you have with feeling depressed?.” All four items had the same response options regarding older persons’ self-rating from 5 = none, 4 = mild, 3 = moderate, 2 = severe to 1 = extreme/cannot do. The higher score indicates a higher level of emotional wellbeing.

Physical wellbeing was assessed using four items: “How much difficulty did you have in vigorous activities?,” “How much difficulty did you have in moving around?,” “How much difficulty did you have with eating or cutting up food?” and “How much difficulty did you have in washing your body/bathing?.” All four items had the same response categories concerning participants’ self-rating from 5 = none, 4 = mild, 3 = moderate, 2 = severe to 1 = extreme/cannot do. The higher score indicates a higher level of physical wellbeing, indicating no or less difficulty doing vigorous activities/exercise, moving around/waking, eating/cutting up food and washing body/bathing.

Psychological wellbeing was assessed from four observed variables: “How much difficulty did you have in remembering things?,” “How much difficulty did you have in concentrating?,” “How often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life?” and “How often have you found that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do?.” The response options for the four items ranged from 5 = none, 4 = mild, 3 = moderate, 2 = severe to 1 = extreme/cannot do and 1 = Never, 2 = Almost never, 3 = Sometimes, 4 = Fairly often to 5 = Very often. The absence of difficulty remembering, concentrating and the ability to cope and control important things indicates higher psychological wellbeing. The WHO (SAGE) Subjective Wellbeing and Quality of Life scale used for emotional, physical and psychological wellbeing has a good construct of validity and reliability in previous studies [33, 46, 47].

Spiritual wellbeing was evaluated by three items: “How satisfied are you with your relationships?,” “Do you belong to a religious denomination?” and “How often in the last 12 months have you attended religious services?.” The response options for belonging to a religion were (1) No, None, (2) Buddhism, (3) Chinese Traditional Religion, (4) Christianity (including Roman Catholic, Protestant, Orthodox and Other), (5) Hinduism, (6) Islam, (7) Jainism, (8) Judaism, (9) Primal Indigenous (including African Traditional and Diasporic) and (10) Sikhism. Responses for attending religious services were (1) Never, (2) Once or Twice Per Year, (3) Once or Twice Per Month, (4) Once Or Twice Per Week and (5) Daily. Responses on satisfaction of personal relationships were rated on a 5-point Likert scale, from “never” to “very often” or “very dissatisfied” to “very satisfied.”

2.2. Confounders

The confounders selected for the study were sex, marital status and perceived general health of respondents. The confounders for the study were also selected based on the literature [48, 49].

2.3. Theoretical Framework of the Study

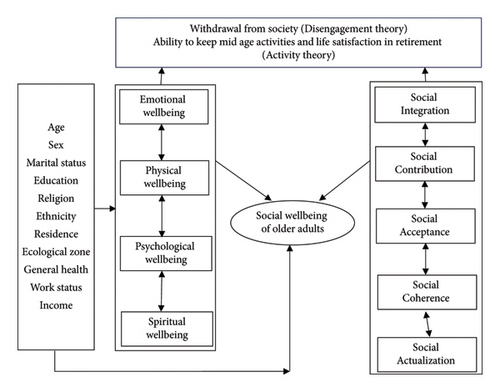

In this study, it was conceptualised that social wellbeing (i.e., social integration, social contribution, social acceptance, social coherence and social actualization) is dependent on the emotional wellbeing (i.e., not being depressed, not worried, not feel neglected and isolated), physical wellbeing (i.e., engaging in moderate to vigorous exercise, ability to eat and cut up food, bath and walk without aid), psychological wellbeing (i.e., ability to remember things, concentrate, cope in difficult times and have control over things in life) and spiritual wellbeing (i.e., belong to a religion, participate in religious services, believe in or harmonious relationship with a supreme being and personal satisfaction).

This implies that older persons who are not depressed, worried and do not feel isolated can engage in exercises, eat and cut up food, bath and walk without aid, can concentrate and cope with difficulties in life, could also participate in religious services, have personal satisfaction which influences how they integrate into society, contribute to their communities, feel accepted by people in society, feel safe in society and have satisfaction with their overall quality of life in society.

In furtherance, it was conceptualised that socioeconomic factors (sex, age, marital status, education, religious affiliation, ethnicity, place of residence, ecological zones, general health, work status and level of income) have a direct relationship with the social wellbeing of older persons. Lastly, the study conceptualised that these confounders have a direct impact on social wellbeing as well as an indirect influence on social wellbeing through the domains of wellbeing such as emotional, physical, psychological and spiritual wellbeing.

In addition, it was conceptualised that social wellbeing (i.e., social integration, social contribution, social acceptance, social coherence and social actualisation) influences the level at which older persons withdraw from society (Disengagement theory) [50] or maintain the activities of middle age for high life satisfaction (Activity theory) [51]. Lastly, the study conceived that improvement in the holistic wellbeing quadrant (emotional, physical, psychological and spiritual) determines whether older persons would withdraw from society (Disengagement theory) or can replace the role losses for higher life satisfaction and overall quality of life (Activity theory). Details are shown in Figure 1.

2.4. Theoretical Framework

Conceptual Framework.

2.5. Hypotheses of the Study

- •

H1: emotional wellbeing positively influences social wellbeing, with higher emotional stability and lower depression leading to greater social integration, contribution and acceptance.

- •

H2: physical wellbeing enhances social wellbeing, as better physical health enables older persons to participate in social activities and maintain independence.

- •

H3: psychological wellbeing contributes to social wellbeing, with cognitive functioning, resilience and autonomy fostering social coherence and actualisation.

- •

H4: spiritual wellbeing promotes social wellbeing by fostering a sense of community, belonging and resilience.

- •

H5: emotional, physical and psychological wellbeing are interconnected and significantly influence social wellbeing.

- •

H6: psychological, physical and spiritual wellbeing interrelate and significantly impact social wellbeing.

2.6. Analysis

The theoretical framework in Figure 1 was tested using the SEM technique. The analysis was done using SPSS Version 26.0 and AMOS Version 23.0 for Windows. The analysis was conducted in two phases. The first phase constituted the measurement models with confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The structural equation modelling with latent variables was conducted in phase two. The data used was a good fit for the study. The data analyses were restricted to older persons 60 years and above.

The theoretical framework (Figure 1) included exogenous latent factors of emotional, physical, psychological and spiritual wellbeing. These exogenous variables were hypothesised to influence each other and directly and indirectly affect the endogenous factor of social wellbeing. Sex, marital status and perceived general health of respondents were also hypothesised to mediate the effects of the holistic wellbeing quadrant on the outcome variable. The maximum likelihood estimation with missing values (MLMVs) was applied in the SEM to handle missing data [31] and obtain adequate information from observations with missing values from the data used.

The models were fitted using the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) approach. Since the chi-square value (χ2) of the likelihood ratio is usually significant with a large sample (n = 1927), four fit indices were used to determine the model fit. These included the Non-normed Fit Index (NFI), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) [52]. The NFI, TLI, and CFI values larger than 0.90 and the RMSEA value smaller than 0.08 denote acceptable model fit. Values larger than 0.90 for NFI, TLI and CFI and 0.08 or lower for RMSEA indicate acceptable model fit [52]. All three relative fit indices (NFI, TLI and CFI) exceeded the 0.90 criterion 0.94, 0.92 and 0.95, respectively [52]. The value of RMSEA (0.06) was also lower than 0.08 [52]. Therefore, an acceptable model fit was achieved. The final model is presented in the results.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Background Characteristics of Respondents

Of the 3, 575 older persons who participated in the study, 1927 fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the present analysis (mean ± SD: 14.1 ± 62.6 years; 43.2% male and 56.8% female). About 4 in every 10 of them were young olds (60–69) and 58% were married. Forty-five percent of the aged, representing the highest, had no formal education. Approximately 73% were Christians and 46% of them were Akans. Also, 47.4% worked full-time and 49.6% lived in the forest zone. Also, about 61% lived in rural areas. Most of the aged had a high level of income and 68.2% had perceived good general health status. Details are shown in Table 1

| Background characteristics | Sample size | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 833 | 43.2 |

| Female | 1094 | 56.8 |

| Age | ||

| 60–69 | 652 | 33.8 |

| 70–79 | 623 | 32.4 |

| 80+ | 652 | 33.8 |

| Mean ± SD | 14.1 ± 62.6 | |

| Marital status | ||

| Not married | 122 | 6.3 |

| Married | 1126 | 58.5 |

| Separated/divorced | 207 | 10.7 |

| Widowed | 472 | 24.5 |

| Education | ||

| No formal education | 867 | 45.0 |

| Primary or JHS | 523 | 27.1 |

| Secondary or higher | 537 | 27.9 |

| Religion | ||

| Christianity | 1402 | 72.8 |

| Islam | 355 | 18.4 |

| No religion/indigenous | 170 | 8.8 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Akan | 886 | 46.0 |

| Ewe | 118 | 6.1 |

| Ga-adangbe | 290 | 15.1 |

| Mande-Busanga | 454 | 23.6 |

| Others | 178 | 9.2 |

| Work status | ||

| Not working | 372 | 19.3 |

| Part time work | 642 | 33.3 |

| Full time work | 913 | 47.4 |

| Ecological zones | ||

| Savannah | 418 | 21.7 |

| Forest | 956 | 49.6 |

| Coastal | 553 | 28.7 |

| Place of residence | ||

| Urban | 753 | 39.1 |

| Rural | 1174 | 60.9 |

| Income | ||

| Low | 448 | 23.3 |

| High | 1479 | 76.7 |

| General health | ||

| Very bad | 168 | 8.7 |

| Moderate | 444 | 23.1 |

| Very good | 1315 | 68.2 |

3.2. Interdependence of the Measures of Social Wellbeing of the Older Persons

The measures of social wellbeing, as analysed in this study, comprised five subdomains made of 16 indicators. The factor loadings for all the indicators of social wellbeing were positive, indicating that a higher score reflects high social wellbeing among older persons. Social integration and social contribution were observed to be positive. However, social integration and coherence are negatively correlated, indicating that increasing social integration is associated with declining social coherence. There was a positive covariance between social contribution and social acceptance; thus, improvement in social contribution also improves social acceptance, and vice versa. Social acceptance positively covary with social coherence but negatively covary with social actualisation. This implies that social acceptance of older persons improves their social coherence but lowers their social actualisation and vice versa.

3.3. Direct Effects of the Holistic Wellbeing Quadrant on Social Wellbeing

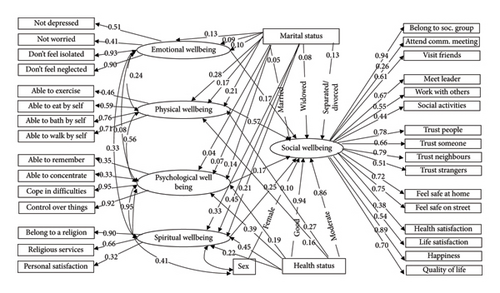

Figure 2 shows the direct of the other domains’ wellbeing (emotional wellbeing (β = 0.17, p < 0.001)), physical wellbeing (β = 0.57, p < 0.001), psychological wellbeing (β = 0.17, p < 0.001) and spiritual wellbeing (β = 0.25, p < 0.001) on social wellbeing of older persons. A unit increase in emotional and psychological wellbeing was both, on average, associated with 0.17 units increase in social wellbeing. Also, on average, a unit increase in physical wellbeing was associated with a 0.57 unit increase in social wellbeing. Finally, an increase of one unit in spiritual wellbeing increased social wellbeing by 0.25 units on average.

Regarding the confounders, the results show that sex (β = 0.10, p < 0.001), perceived general health status (moderate (β = 0.86, p < 0.001) and good (β = 0.94, p < 0.001)) and marital status (married (β = 0.07, p < 0.001), separated/divorced (β = 0.13, p < 0.001) and widowed (β = 0.08, p < 0.001)) had a statistically significant (p < 0.01) and direct effects on social wellbeing. Females, on average, had a higher social wellbeing by 0.10 units when compared with males. Also, older persons who rated their general health status as moderate, on average, had improved social wellbeing by 0.86 units while those who reported good general health status had higher social wellbeing by 0.94 units when compared with those who reported poor general health status. For marital status, the results show that respondents who were married, separated/divorced and widowed, on average, had higher social wellbeing by 0.07, 0.13 and 0.08 units, respectively, when compared to those who never married.

3.4. Indirect Effects of the Holistic Wellbeing Quadrant on Social Wellbeing

The indirect associations also show that the effects of emotional, physical, psychological and spiritual wellbeing on the social wellbeing of older persons were mediated by their marital status. Older persons who were ever married (currently married (β = 0.10, p < 0.001), separated/divorced (β = 0.09, p < 0.001) and widowed (β = 0.13, p < 0.001)) had higher emotional wellbeing, which influenced their social wellbeing. So, for older persons who were ever married, a unit increase in their emotional wellbeing was associated with an increase of 0.10, 0.09 and 0.13, respectively, in their social wellbeing, on average, when compared with those who never married. Also, of older persons who were ever married, a unit increase in physical wellbeing, on average, was associated with an increase of 0.28 (p < 0.001), 0.17 (p < 0.001) and 0.21 (p < 0.001), respectively, in their social wellbeing compared with those never married. The results also show that respondents who were ever married had improved psychological and spiritual wellbeing, which further enhanced their social wellbeing when compared with those who never married, as detailed in Figure 2.

Furthermore, results in Figure 2 show that the sex of the respondent operates through physical (β = 0.10, p < 0.001), psychological (β = 0.41, p < 0.001) and spiritual (β = 0.31, p < 0.001) wellbeing to influence the social wellbeing of older persons. For females, on average, a unit increase in their physical, psychological and spiritual wellbeing increased their social wellbeing by 0.10, 0.41 and 0.31 units, respectively, when compared with males. Also, the effects of physical, psychological and spiritual wellbeing on the social wellbeing of older persons were mediated by their perceived general health status.

The effects of physical wellbeing on social wellbeing were mediated by moderate (β = 0.16, p < 0.001) and good (β = 0.27, p < 0.001) general health status. Thus, a unit increase in their physical wellbeing was associated with 0.16 and 0.27 units increase in their social wellbeing. The effect of psychological wellbeing on social wellbeing was influenced by perceived general health status (moderate (β = 0.39, p < 0.001) and good (β = 0.19, p < 0.001)). For respondents with moderate and good perceived general health, an increase in psychological wellbeing by 0.39 and 0.19 units was associated with an increase in social wellbeing when compared with those who reported poor perceived general health. Furthermore, for respondents who reported moderate (β = 0.22, p < 0.001) and good (β = 0.45, p < 0.001) perceived general health status, improvement in spiritual wellbeing was associated with improved social wellbeing.

3.5. Covariances Among the Holistic Wellbeing Quadrant and Their Effects on Social Wellbeing

The results further show interdependence among the holistic wellbeing quadrant, which further influences the social wellbeing of older persons (Figure 2). Emotional wellbeing positively covary with physical and psychological wellbeing to impact the social wellbeing of older persons. This indicates that healthy emotional wellbeing positively impacts physical and psychological wellbeing to influence the social wellbeing of older persons and vice versa. Furthermore, the results show that psychological wellbeing is highly correlated with physical and spiritual wellbeing, while spiritual wellbeing also positively covary with the emotional wellbeing of older persons. The positive covariance observed between the psychological wellbeing of older persons and their physical and spiritual wellbeing implies that high psychological wellbeing improves the physical and spiritual wellbeing of older persons to positively impact their social wellbeing. Therefore, older persons with high psychological wellbeing also had high physical and spiritual wellbeing and, thus, high social wellbeing. Also, older persons with high spiritual wellbeing had high emotional wellbeing and, therefore, high social wellbeing.

4. Discussion

This study investigates the interrelationships between the holistic wellbeing quadrant—comprising emotional, physical, psychological and spiritual wellbeing—and social wellbeing among older persons in Ghana. The findings reveal that all four domains of wellbeing significantly enhance social wellbeing, with physical wellbeing emerging as the strongest predictor, followed by spiritual, emotional and psychological wellbeing. These domains are interrelated, with each positively influencing the others to collectively improve the overall social wellbeing of older persons.

4.1. Emotional Wellbeing and Social Wellbeing (H1)

The study hypothesised (H1) that emotional wellbeing positively influences social wellbeing, with higher emotional stability and lower levels of depression fostering greater social integration, contribution and acceptance. It was observed that emotional wellbeing is rooted in the ability to maintain positive feelings, cope with stress and avoid isolation. Keyes [28] found that older persons with higher emotional stability and life satisfaction are more likely to engage in social activities, maintain robust social networks and experience a sense of belonging in their communities. Conversely, emotional distress, such as loneliness or depression, can lead to social isolation and reduced participation in community activities [42]. This is particularly relevant in Ghana, where older persons often face emotional challenges due to the loss of loved ones, reduced independence and shifting family dynamics, which can negatively impact their social integration and overall wellbeing [23]. Gyasi et al. [1] highlighted that older Ghanaians who maintain emotional wellbeing are more likely to participate in community activities and sustain social connections, which are crucial for their quality of life. These findings align with Taylor et al. [22], who emphasised that emotional wellbeing is a key predictor of social engagement and life satisfaction, especially in developing countries where social support systems may be limited.

4.2. Physical Wellbeing and Social Wellbeing (H2)

The study also hypothesised (H2) that physical wellbeing enhances social wellbeing, as better physical health enables older persons to participate in social activities and maintain independence. It was found that physical wellbeing is a critical determinant of social wellbeing, as it facilitates social connections by allowing older persons to engage in communal activities. Research consistently shows that physical activity is a key factor in maintaining social connections. For example, Weinstein et al. [42] found that older persons who engage in regular physical activities, such as walking or gardening, report higher levels of social integration and satisfaction. These activities not only improve physical health but also provide opportunities for social interaction, which is essential for maintaining social wellbeing [42]. Similarly, Nicklett et al. [53] highlighted that access to physical activities, particularly in community settings, enhances social cohesion. Their study found that older persons who participated in group exercises or community gardening projects reported stronger social ties and a greater sense of belonging [53]. In the Ghanaian context, physical independence is a significant predictor of social participation and satisfaction. Older persons who are physically capable of performing daily activities without assistance are more likely to engage in social and communal activities, leading to higher levels of social wellbeing [25]. This aligns with Gyasi et al. [1], who noted that physical independence allows older persons to maintain their roles in the community, thereby enhancing their social integration and overall quality of life. Physical wellbeing also contributes to social cohesion by enabling older persons to participate in communal activities, such as attending community events, religious services or family gatherings, which are vital for maintaining social networks in Ghana [1].

4.3. Psychological Wellbeing and Social Wellbeing (H3)

Psychological wellbeing, which encompasses cognitive function, coping mechanisms and a sense of control over daily activities, positively influence social wellbeing. This supports H3, which posits that psychological wellbeing fosters social coherence and actualisation through cognitive functioning, resilience and autonomy. Research shows that older persons with higher psychological wellbeing are more resilient, better able to handle life’s challenges and more likely to actively participate in their communities [27]. Psychological resilience—the ability to adapt to stress—plays a key role in maintaining social connections and community engagement. Older persons with strong psychological wellbeing are more likely to contribute to their communities and experience social acceptance and coherence [41]. Cognitive functioning, a component of psychological wellbeing, is essential for social interactions. It enables older persons to process social cues, engage in conversations and participate in community activities, all of which are critical for social integration. Studies, such as those by Yu et al. [29], show that better cognitive function is linked to stronger social networks and higher social wellbeing. This is particularly relevant in Ghana, where older persons often face psychological challenges due to economic hardships, loss of social roles and limited access to mental health services [1]. These challenges can hinder social connections, highlighting the importance of psychological wellbeing in promoting social integration. In addition, psychological wellbeing fosters a sense of autonomy and control, which is crucial for social actualisation. Older persons who feel in control of their lives are more likely to engage in community activities and derive satisfaction from their social roles. This aligns with Ryff’s [27] findings that autonomy and purpose in life are key to social wellbeing. In Ghana, where older persons often experience shifting family dynamics and reduced independence, maintaining psychological wellbeing can help reduce social isolation and enhance their ability to contribute meaningfully to their communities.

4.4. Spiritual Wellbeing and Social Wellbeing (H4)

The study’s findings highlight the impact of spiritual wellbeing on social wellbeing, as engagement in religious practices fosters a sense of belonging and community. This finding supports Hypothesis 4 (H4), which posits that spiritual wellbeing promotes social well-being by fostering community, belonging and resilience, particularly in Ghana’s culturally rich spiritual context. This aligns with previous research showing that religious practices strengthen social ties and provide emotional and psychological support [31, 38]. In Ghana, where spirituality is central to daily life, religious communities offer social support, identity and networks that enhance social integration and acceptance [14]. Spiritual practices such as prayer and communal worship also reduce stress and promote resilience [31]. The study further highlights the interdependence between spiritual wellbeing and emotional wellbeing, with higher spiritual wellbeing linked to greater emotional stability and resilience [31]. This is particularly significant in Ghana, where religious communities provide crucial support for older persons facing challenges like loneliness or declining health [1]. The findings align with the biopsychosocial–spiritual model [16], emphasising spirituality’s role in enhancing psychological resilience and social integration. Older persons engaged in spiritual practices are more likely to maintain a positive outlook, cope with challenges and feel a sense of purpose, fostering meaningful community engagement [10].

4.5. The Interconnectedness of Emotional and Psychological Wellbeing (H5)

The study findings support the hypothesis (H5) that emotional wellbeing and psychological wellbeing are interconnected and significantly influence social wellbeing among older persons. Specifically, emotional wellbeing was found to positively correlate with both physical and psychological wellbeing. This interdependence suggests that higher emotional stability can mitigate depression and anxiety, thereby supporting both physical and mental health in older persons [35]. This reciprocal relationship indicates that positive emotional wellbeing enhances an individual’s capacity to cope with physical ailments and stressors, enabling older persons to maintain their social roles and interactions throughout the ageing process. This, in turn, leads to greater life satisfaction and social wellbeing, as informed by the Activity Theory [51]. The relationship between emotional wellbeing and physical health is well documented. Keyes and Ryff [28] found that older persons with higher emotional stability and life satisfaction are more likely to engage in social activities and maintain strong social networks, which support physical health. Conversely, emotional distress, such as loneliness or depression, is linked to physical health decline, including cardiovascular risks and weakened immune function [34].

In Ghana, emotional wellbeing enables older persons to participate in community activities and maintain social connections, enhancing their quality of life [1]. Psychological wellbeing, closely tied to emotional wellbeing, is crucial for maintaining social connections and community engagement. Older persons with higher psychological wellbeing are more resilient, better able to handle life’s challenges and more likely to participate in their communities [29]. Cognitive functioning, a key component of psychological wellbeing, facilitates social interactions by enabling older persons to process social cues, engage in conversations and participate in community activities, all of which are vital for social integration [27]. The study emphasises the interconnectedness of emotional, physical and psychological wellbeing, where improvements in one domain positively influence others. For example, emotional wellbeing enhances psychological resilience, which supports physical health by reducing stress and improving immune function [10]. This interconnectedness is especially relevant in Ghana, where older persons face psychological challenges due to economic hardships, loss of social roles and limited mental health access [1]. Maintaining emotional and psychological wellbeing helps reduce social isolation and enables older persons to contribute meaningfully to their communities.

4.6. The Interconnectedness of Psychological, Physical and Spiritual Wellbeing (H6)

The study results support the hypothesis (H6) that psychological, physical and spiritual wellbeing interrelate and significantly impact social wellbeing. Psychological wellbeing, the ability to maintain mental focus, cope with life’s challenges and feel a sense of control, is closely linked to greater physical autonomy. Research shows that individuals with higher psychological wellbeing manage physical health challenges more effectively, enhancing their ability to engage in social activities and maintain independence [1, 29]. For instance, older persons with strong psychological resilience are more likely to participate in community activities, maintain social networks and experience a sense of belonging, all of which boost social wellbeing [27]. In Ghana, psychological wellbeing is crucial for fostering social integration and reducing isolation among older persons [1]. Spiritual wellbeing, characterized by a sense of meaning, purpose and connection to something greater than oneself, is especially significant in the Ghanaian context. Spiritual practices such as prayer and communal worship provide emotional and psychological support, enhancing strength and reducing stress [10, 28]. Given the deep-rooted role of spirituality and religion in daily life in Ghana, spiritual wellbeing fosters a sense of community and belonging, directly boosting social wellbeing [1]. Older persons who engage in spiritual practices are more likely to maintain positive social relationships, participate in community activities and experience a sense of purpose [38]. Physical wellbeing, which involves maintaining functional health and managing chronic conditions, is also closely tied to spiritual wellbeing. Studies show that physically active and healthy older persons are more likely to participate in spiritual and religious activities, further enhancing their social wellbeing [22, 53]. In Ghana, where communal activities and social support networks are vital, physical wellbeing enables older persons to engage in religious and social activities, fostering a strong sense of belonging and community [1].

The study shows that physical and spiritual wellbeing contributes to sustained social involvement, counteracting withdrawal tendencies by the disengagement theory, suggesting that some individuals may naturally withdraw from social roles in old age [14]. Hence, maintaining high spiritual wellbeing through religious participation and emotional wellbeing through positive social interactions facilitates ongoing social wellbeing. This corroborates findings on how spiritual engagement provides psychological and social support, reinforcing wellbeing through community belonging and emotional connection [19, 39].

The findings in this study emphasise that sex, marital status and general health status significantly mediate the relationship between wellbeing domains (emotional, physical, psychological and spiritual wellbeing) and social wellbeing. Older females reported higher social wellbeing than males [49]. This is attributed partly to increased social engagement in activities such as family care, church involvement, and community interactions. In Ghana, women, due to their traditional caregiving roles and communal interactions, often exhibit higher levels of social engagement and support networks than men [49]. These gender-based social networks support the Activity Theory, which posits that staying active in meaningful roles fosters life satisfaction and wellbeing in older persons [51].

The findings show that older persons who are married, separated or widowed have higher social wellbeing than those who were never married. This trend can be explained by the companionship, support and social connections often derived from marital relationships, which extend beyond marriage through widowhood or separation [47]. Marriage has been found to act as a protective factor that offers social and emotional support, facilitating positive social wellbeing outcomes [48, 49].

The study revealed that older persons with perceived moderate or good health reported higher social wellbeing, as better health enables more participation in community activities and social interactions. This aligns with disengagement theory, which suggests that poor health can drive social withdrawal in older persons [50]. However, healthy individuals, particularly those who can maintain physical independence, are more likely to sustain social connections, as informed by the Activity theory [24].

The study highlights healthier older persons in Ghana, through better general health and physical independence, can fully engage in social and community activities, which positively impact their social wellbeing [24]. This echoes the activity theory of ageing, which proposes that maintaining social roles, physical activity and engagement in later life enhances life satisfaction. By contrast, the Disengagement theory posits a gradual withdrawal from societal roles as an adaptive ageing process [50]. However, findings suggest that better physical health and independence challenge this view, enabling older persons to continue meaningful participation in their communities, which fosters social wellbeing [24].

Studies by Taylor et al. [22] and Nicklett et al. [53] support the assertion that physical activity is essential for social wellbeing, showing that older persons who engage in physical activities like walking or gardening are more socially integrated and satisfied. Physical independence enhances social wellbeing by enabling participation in social and communal activities, fostering a sense of belonging and security within communities [47].

Furthermore, the study shows that psychological and spiritual wellbeing are crucial for both physical and social wellbeing. Older persons who maintain cognitive abilities, manage daily challenges and engage in social activities report higher social coherence and integration [39]. This interdependence across physical, psychological, emotional and spiritual domains supports a holistic view of wellbeing, where improvements in one domain of wellbeing enhance other domains of wellbeing, cumulatively boosting social wellbeing. This interconnectedness highlights the need for multidimensional support in ageing, encouraging interventions that consider physical, emotional and spiritual needs to improve social inclusion and life satisfaction.

Lastly, the study’s findings highlight that spiritual wellbeing positively interacts with emotional and psychological wellbeing to enhance social cohesion. Religious participation often correlates with improved mental resilience, which bolsters one’s capacity to engage with others and foster a fulfilling social life [20]. Spiritual practices and beliefs offer coping mechanisms that are instrumental in psychological resilience and stress reduction, as found in studies on the psychological impact of religious engagement among older populations [14].

5. Conclusion

This study assessed the interrelationships between the holistic wellbeing quadrant and social wellbeing in older persons in Ghana. The study highlights the interconnectedness of emotional, physical, psychological and spiritual wellbeing. Improvements in one domain often enhance others, leading to holistic wellbeing. Physical wellbeing emerged as the strongest predictor of social wellbeing among older persons. This indicates the importance of maintaining physical health through accessible healthcare, regular physical activity programs and nutritional support. Spiritual wellbeing significantly impacts social wellbeing by promoting community participation and emotional resilience. In the Ghanaian context, where spirituality is deeply integrated into social life, faith-based organisations can play a vital role in providing social and emotional support. Sex, marital status and perceived general health status significantly mediate the relationship between wellbeing and social wellbeing. Policies should prioritise holistic wellbeing by promoting physical activity, providing accessible healthcare, supporting mental health services and encouraging spiritual engagement. Community-based initiatives, such as wellness centres offering physical, emotional and spiritual support, can provide a comprehensive approach to healthy ageing in Ghana’s older population.

5.1. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

The study employs a comprehensive multidimensional analysis that explores the interplay between emotional, physical, psychological and spiritual wellbeing and its impact on social wellbeing among older persons in Ghana. This holistic approach provides valuable insights into the various factors influencing wellbeing within this demographic. The use of SEM further enhances the analysis, allowing for a robust examination of both direct and indirect relationships among different domains of wellbeing. This method effectively accounts for the complexity and interdependence of these factors, leading to a deeper understanding of their collective influence on social wellbeing. In addition, the research benefits from a large, nationally representative sample drawn from Wave 2 of the WHO’s Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE), which includes 1927 individuals aged 60 and above. This substantial dataset enhances the generalizability of the findings and emphasizes the cultural and contextual relevance of the study in addressing the needs of older persons in Ghana.

Despite its strengths, the study is limited by its use of cross-sectional data, which restricts the ability to infer causation among the observed relationships between wellbeing domains. As a result, the findings reflect associative patterns rather than definitive causal pathways, highlighting the need for longitudinal studies to validate these relationships further. In addition, the reliance on self-reported measures for assessing wellbeing introduces potential bias, as participants’ perceptions may be shaped by subjective factors, impacting the accuracy of the reported outcomes. The study also addresses some socioeconomic variables but could have considered additional external influences, such as community or environmental factors, to achieve a more nuanced understanding of social wellbeing in older persons. Standardized scales may not fully capture culturally specific aspects of wellbeing in Ghana, such as traditional healing or communal support, limiting contextual relevance. Finally, while the study is culturally relevant to Ghana, its findings may not fully apply to older populations in different socioeconomic or cultural contexts, necessitating further cross-cultural validation to enhance its applicability in diverse settings.

5.2. Implications and Future Research

Given the study’s finding that physical, emotional, psychological and spiritual wellbeing collectively enhance social wellbeing, policies should adopt a holistic approach to elderly care. Integrate health programs that address physical health alongside emotional support and spiritual engagement can foster overall wellbeing. Prioritise accessible, affordable and high-quality healthcare for older persons, focusing on preventive care, chronic condition management and rehabilitation services, given physical wellbeing’s strong link to social wellbeing. Engage faith-based and community organisations to promote social inclusion and emotional resilience through religious and cultural activities, strengthening social ties and improving quality of life. Develop targeted programs for older men, who may face higher social isolation risks, while leveraging the higher social wellbeing reported by older women. Foster social connections for older persons, particularly widowed or unmarried individuals, through community programs that encourage social interaction. For practical implications, holistic care models should be adopted for multidimensional care approaches addressing emotional, physical, cognitive and spiritual wellbeing to enhance social wellbeing. Community engagement is needed to organise group exercises, social events and spiritual gatherings to maintain social connections and prevent isolation. Training for health professionals is crucial to recognise interconnected wellbeing dimensions, emphasising cultural context and spirituality’s role in older persons’ lives.

Concerning implications for future research, future research should explore the causal relationships between wellbeing dimensions over time, given the cross-sectional nature of this study. Further studies should investigate how cultural practices and beliefs influence the interconnections between wellbeing domains and social wellbeing. Research on the effectiveness of integrated wellbeing interventions in enhancing social wellbeing among older persons in Ghana can provide evidence-based strategies for policy and practice.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding was received for the current study.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by giving access to the dataset by the World Health Organization, Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE).

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analysed during the current study are available at https://apps.who.int/healthinfo/systems/surveydata/index.php/access_licensed/track/4087.