Becoming Experts: Life Changes, Adaptation, and Learning of Stroke Survivors’ Informal Caregivers

Abstract

Background: Social and health trends (e.g., the aging population and growth of chronic diseases) place stroke and informal care as global concerns. After a stroke, most survivors return home relying primarily on informal caregivers, who ensure essential daily support. Although informal care’s adaptive and learning dimensions are evident, it has rarely been problematized. Understanding what and how learning processes emerge in the context of informal caregiving may be useful for the development of health, social, and educational strategies that support caregiving contexts.

Methods: This mixed methods’ study included informal caregivers of stroke survivors hospitalized between September 2018 and August 2019 in all Stroke Units of Northern Portugal. Structured questionnaires (n = 443) were filled in and analyzed through chi-square tests and logistic regression models. About 12–18 months later, semistructured interviews were carried out (n = 37), and a reflexive thematic analysis was performed.

Results: Adaptation to informal care is supported by learning processes that are driven by the impact that care assumes on caregivers’ lives, as shown in both quantitative and qualitative data. Qualitative findings supported that throughout the care trajectory learning is influenced by enablers and barriers, with practice and experience playing a central role. Learning needs and proposals to facilitate the learning and adaptation were generated.

Conclusion: Becoming an informal caregiver is a dynamic, impactful, and experiential learning-based process where individual and social spheres interact. Integrated health, social, and educational resources and services within proximity and people-centered logics can facilitate and improve the adaptation to this unexpected role, fostering caregivers’ wellbeing and ultimately improving care quality within communities.

1. Introduction

Stroke is a global health concern ranking as one of the leading causes of disability and death, affecting millions of people annually [1, 2]. Advances in stroke acute management and therapeutic options promoted an increase in survival rates [3]. However, some people develop stroke-related impairments that limit their independence in daily life activities and functioning [4]. In consequence, many stroke survivors return home with diverse daily care needs, which are often met by family members who assume the role of caregivers without financial remuneration. After the stroke survivor’s hospital discharge, the informal caregivers must immediately respond to new demands, causing life changes, namely, practical (e.g., home modifications), emotional (e.g., burden), behavioral (e.g., lifestyle changes), and social changes (e.g., isolation) [5–8]. The new reality forces families to adapt in the short, medium, and long term [8] and demand a continuous, dynamic, and heterogeneous process of acquiring skills and knowledge, especially through experience [9–11], to ensure the necessary conditions for the survivor’s recovery. This practical exercise of answering and adapting to care demands can be understood as a formative activity since it affects informal caregivers’ previous skills and knowledge framework.

Adult learning and education continue to be framed within qualification and requalification logics, appealing to its importance to “diversity,” “continuity,” and “globality” [12–14], translating into the development of support strategies directed to the labor market specificities [15]. This work intends to contribute in the opposite direction by framing adult education beyond formal contexts and labor logics, recognizing that learning processes extend to typically noneducational contexts, as is the case of informal care [16]. Given care’s unexpected and unplanned nature, the caregivers’ adaptation to new individual, peer, and social demands [17, 18] essentially become experimental exercises. Recognizing the meaningful learning potential of these experiences, framing the informal care in adult education and lifelong learning fields values the epistemology of experience and acknowledges its formative potential [9, 10].

Learning through experiences, especially in the context of lifelong education, has been debated, and its importance has been highlighted in the literature [9, 10, 19] emerging concepts such as experiential learning—a conscious activity that places the subjects in interaction with themselves, with others, and with the environment that surrounds them, generating unexpected learning [20, 21]. These processes of producing reality from each experience are based on discovery, improvisation, and acquisition of new knowledge, in which there is “tension and rupture with the frames of reference” [10]. This dynamic aligns with Kolb’s experiential learning cycle [22], as informal caregivers continuously engage in a cyclical process of learning that involves concrete experiences, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation. The initial challenges of caregiving may generate new, often unexpected, experiences that require immediate responses, prompting reflection on their effectiveness. Over time, caregivers can integrate these reflections into broader conceptual understandings of care, refining their strategies and adapting to evolving demands. This iterative process highlights the fluid nature of learning in informal caregiving, where adaptation is not linear but rather shaped by ongoing negotiation between past experiences, present challenges, and future uncertainties. Since people’s learning paths are closely related to their contexts (historical, social, economic, political, territorial, and affective), reinforcing the situated and relational dimensions of experiential learning, different formative effects are produced [9]. Therefore, the conditions in which the informal care experimental learning takes place may impact the caregiving experiences and the outcomes of care. Thus, it is essential to understand in depth what and how learning processes emerge in the context of informal caregiving, to contribute to more equitable systems. Problematizing informal care from a social and educational point of view can promote conditions for developing skills and autonomy [23, 24] and learning resources, reducing the burden and feelings of lack of information and preparation [25, 26]. Ultimately, contributions can be made to designing and developing policies, research, and community interventions targeted to informal caregivers’ contexts, knowledge, preferences and needs. Thus, by integrating quantitative and qualitative data, this study aims to understand the changes in informal caregivers of stroke survivors’ lives and their adaptation and learning processes triggered by this role.

2. Materials and Methods

This observational and cross-sectional mixed methods’ study used a parallel convergent design [27]. The merging of quantitative and qualitative results provides a multiple perspective understanding of the research question: “After assuming the caring role of stroke survivors, what changes occurred in informal caregivers’ lives, and how did they experience their learning in the process of adapting to the new reality?” [28]. This study is assembled within the CARESS research project1, which was described in detail elsewhere [29].

All stroke survivors hospitalized between September 2018 and August 2019 in one of the 12 Stroke Units of the Northern Region Health Administration of Portugal (ARS-Norte) and their informal caregivers (unpaid individuals who care for people who need help taking care of themselves) were invited to participate in the CARESS study, 18–24 months poststroke event (n = 2170). Of all survivors with an informal caregiver who agreed to participate in the study, none of the caregivers refused to participate. Formal caregivers, individuals who do not understand or speak Portuguese, or who have language and/or cognitive disorders (e.g., dysphasia, dementia, memory loss, and deafness/hearing loss) were excluded. After acceptance to participate in the study, a meeting was scheduled according to the caregivers’ availability and convenience to administer a structured questionnaire, preferentially face-to-face or by telephone. Then, a subsample of informal caregivers was enrolled in semistructured qualitative interviews, according to their availability and convenience (in person, by telephone/videoconference).

This study was approved by the Ethics Committees and the respective Data Protection Offices of all 12 Stroke Units of the Northern Region Health Administration of Portugal. The work was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and with the General Data Protection Regulation to comply with the requirements of the European Regulation regarding scientific research and the protection of personal data. Ethical principles of the Ethical-Deontological Regulation Instrument: Ethics Charter of the Portuguese Society of Educational Sciences [30] and the principles of “hospitality ethics” based on values such as welcoming, proximity, responsibility, and kindness, were also followed [31]. Integrity, confidentiality, privacy, and respect for the rights of participants were ensured, and after providing clear, transparent, and detailed information about the study, their informed consent was obtained. Furthermore, the confidentiality and anonymity of all materials were guaranteed, as well as the minimization of possible negative consequences of participation in the study [32].

2.1. Quantitative Study: Participants, Data Collection, and Analysis

Informal caregivers were invited through contact with stroke survivors. Of the 2170 eligible stroke survivors, 1775 agreed to participate by completing a questionnaire (participation rate of 81.8%). For the current work, only informal caregivers were enrolled (n = 443). The main reasons for participation refusal were lack of time, lack of interest in the study, and psychological unavailability (e.g., when participants reported being emotionally unavailable to share their feelings). The questionnaires were administered by trained researchers and included the following dimensions: sociodemographic characteristics, caregiving-related characteristics, perceived general health status, health-related behaviors (HRBs), work-related changes, and financial impact caused by stroke.

Informal caregivers’ age was considered at the time of the questionnaire and categorized as < 65 years and ≥ 65 years. The marital status was grouped into two categories: married/cohabiting with the partner and single/divorced/widowed. The education level was considered as the number of completed years of education and categorized as ≤ 4 years, 5–9 years, 10–12 years, and > 12 years. The household monthly income was stratified into ≤ 1000€, > 1000€, and does not know/prefers not to answer. The neighborhood was categorized as rural or urban, according to the participant’s perceptions. Responses about children were categorized as yes or no.

Regarding caregiving-related characteristics, it was collected information about the relationship with the stroke survivor (sons/daughters, spouses, parents, siblings, grandchildren, sons-in-law, sisters-in-law, and stepdaughters), residence (no changes or moved into survivor’s house/a new residence), hours of care provision per day (categorized as ≥ 8 h/day and < 8 h/day), previous experience of informal caregiving (yes/no), care provided to more than one care recipient (not necessarily the stroke survivor), and stroke impact. The stroke impact was assessed through the poststroke checklist [32] and grouped into five categories: motor (items 2, 3, 4, and 10), bowel and bladder (item 15), cognitive (items 7 and 9), emotional (items 8 and 11), and pain (item 5).

The changes in the informal caregivers’ lives were evaluated through the assessment of the (1) perceived general health status changes; (2) HRB changes; (3) work-related changes; and (4) financial impact caused by caregiving. The perceived general health status changes were evaluated through a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from weak (1) to excellent (5); and much worse (1) to much better (5). Self-reported data about tobacco, alcohol consumption, dietary habits, physical activity, and sleep were collected to assess the changes in HRB. The improvement in HRB was considered when three or more HRB had improved, and the worsening in HRB was considered when three or more HRB worsened.

Work-related changes were considered when informal caregivers did not return to a previous job (similar or modified or starting a new job) at the time of the questionnaire. Thus, it was included in the analysis of informal caregivers who suspended work, retired, or previously left their jobs to provide care. The financial impact was considered when informal caregivers answered “yes” to the question, “Did the stroke episode cause financial changes/problems in the family?”

The statistical analysis was performed using STATA 15.1 (College Station, TX, 2009). Sociodemographic and caregiving-related characteristics of the participants were described as counts and proportions, and data were compared using the chi-square test. Unconditional logistic regression models were used to compute crude odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for assessing the association between the sociodemographic and care characteristics and perceived general health status, HRBs, work-related changes, and financial impact. The associations were considered significant when the CI did not include 1.

2.2. Qualitative Study: Participants, Data Collection, and Analysis

Qualitative semistructured interviews were performed to pursue a deeper insight into the views and experiences of informal caregivers regarding the changes in their lives and the learning processes after assuming the caregiving role. A subsample of informal caregivers that participated in the quantitative study was contacted for an interview, approximately 12–18 months after filling out the questionnaire (November 2020–February 2022). This time gap was selected to enable participants to reflect on their experiences with a greater and in-depth perspective, highlighting key learning moments and adaptation processes that may not have been evident in the early stages. To obtain a maximum variation of views and experiences, the participants were purposively sampled to include heterogeneity regarding sex, age, and stroke healthcare unit in which stroke survivors were admitted. Participants were selected from a database of stroke survivor-caregiver dyads who had previously participated in the quantitative study. Initially, potential participants were randomly chosen and contacted for the qualitative phase. After each interview was scheduled, the characteristics of the recruited participants (sex, age, and stroke healthcare unit) were reviewed to ensure heterogeneity in the sample. This iterative process allowed for purposive sampling, ensuring maximum variation in views and experiences while maintaining methodological rigor.

Among the caregivers contacted to participate, those whose stroke survivors became institutionalized (n = 4) or died (n = 3), and previous informal caregivers who no longer assumed this role (n = 2) were excluded. Thus, 48 informal caregivers were invited to attend the interview. Among those, 10 caregivers refused to be interviewed due to lack of time (n = 5), psychological unavailability (n = 4), and lack of interest in the study (n = 1). One of the interviews was eliminated due to the imperceptibility of the audio recording. The final sample included 37 informal caregivers (24 females and 13 males). The interviews were conducted telephonically (n = 20) and face-to-face at participants’ homes (n = 17). Informal caregivers were spouses (n = 20), children (n = 12), sons-in-law/daughters-in-law (n = 3), grandchildren (n = 1), and siblings (n = 1). Interview duration ranged from 15 to 98 min (mean: 44 min). The interviews’ audios were digitally recorded after informed consent. Subsequently, verbatim transcription and validation for accuracy and precision were carried out. The interviews were collected and analyzed simultaneously to identify the moment of data saturation (when no new and/or significant themes emerged from the interviews) and the consequent cessation of participants’ recruitment.

Considering that the interview guide was used within the scope of a larger project, the entire content of each interview was analyzed to capture all data related to the caregivers’ learning processes. However, specific questions were drawn that covered the (i) experience of being an informal caregiver, namely, the positive and negative aspects; (ii) changes in informal caregivers’ lives; (iii) changes in the caregiving role over time; (iv) main strategies used to facilitate the caregiving role; and (v) the main learnings that the role of caregiver brought. The interviews were carried out by experienced researchers, who had previously administered the questionnaires and who were trained to ensure quality. A reflexive thematic analysis was carried out using NVivo 14 (QSR International, USA, 2023) to identify and explore patterns of meaning across the interviews [33, 34]. Following Braun and Clarke’s approach, this analysis emphasized the researcher’s subjectivity and continuous reflexive engagement throughout the process. We critically examined our theoretical and epistemological assumptions, actively reflecting on their influence on data interpretation. Our engagement with the data was recursive rather than linear, involving an iterative process of moving between coding and interpretation to develop a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the research problem. Rather than treating data analysis as a passive exercise, we approached it as an evolving and interpretative process shaped by the researcher’s engagement. Instead of merely summarizing data domains, we identified patterns of shared meaning, each underpinned by a central organizing concept. Therefore, based on the research question, and after the familiarization with the data, a systematic data coding was carried out, and quotations of informal caregivers with similar meanings were inductively synthesized into categories and themes.

In addition to the data saturation, triangulation strategies were applied to ensure the rigor and quality of the analysis, namely, theory triangulation and data source triangulation [35]. During the process, different theories or hypotheses were mobilized (theory triangulation) to support and/or refute the findings. Throughout the qualitative analysis process and in the data merging phase, the quantitative and qualitative findings were triangulated (data source triangulation) to join multiple perspectives and validate the data. To enhance the reliability of the analysis, a detailed audit trail of analytic decisions was maintained, and regular discussions were conducted within the research team to ensure consistency and coherence in codebook development. Finally, the most illustrative verbatim quotes of the meanings, views, and experiences emerging from the narratives were selected, translated, and revised.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Participants

Most informal caregivers were female, aged below 65 years, and married or cohabiting with a partner. Nearly 40% completed four or fewer years of education, slightly more than 50% had ≤ 1000 euros per month of household income, and lived in rural areas, and 84.6% had children (Table 1). Regarding the caregiving-related characteristics, around 48% of caregivers were sons/daughters of stroke survivors, 75.5% maintained the same residence, 85.1% spent less than 8 hours per day caring for the stroke survivor, 69.7% had no experience of informal caregiving, and nearly 90% does not assume the informal care of other people rather than the stroke survivors. Concerning the survivor’s stroke impact, 99% reported motor impact, 55.8% bowel and bladder impact, 85.5% cognitive impact, 79.5% emotional impact, and 33.7% pain-related impact.

| Sociodemographic characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 387 (87.4) |

| Male | 56 (12.6) |

| Age (years) | |

| < 65 | 307 (69.9) |

| ≥ 65 | 132 (30.1) |

| Marital status | |

| Married/cohabiting | 354 (80.1) |

| Single/divorced/widowed | 88 (19.9) |

| Educational level (years) | |

| ≤ 4 | 188 (42.6) |

| 5–9 | 140 (31.8) |

| 10–12 | 65 (14.7) |

| > 12 | 48 (10.9) |

| Household income (€/month) | |

| ≤ 1000 | 244 (55.2) |

| > 1000 | 139 (31.5) |

| Does not know/prefer not to answer | 59 (13.4) |

| Neighborhood | |

| Rural | 228 (51.9) |

| Urban | 211 (48.1) |

| Children | |

| Yes | 373 (84.6) |

| No | 68 (15.4) |

| Caregiving-related characteristics | |

| Relationship | |

| Son/daughter | 211 (47.7) |

| Spouse | 163 (36.9) |

| Othera | 68 (15.4) |

| Residence | |

| Without changes | 333 (75.5) |

| Moved into survivor’s house/new residence | 108 (24.5) |

| Hours of care provision/day | |

| ≥ 8 h | 376 (85.1) |

| < 8 h | 66 (14.9) |

| Previous experience of informal caregiving | |

| No | 308 (69.7) |

| Yes | 134 (30.3) |

| Multiple informal caregiverb | |

| No | 383 (89.9) |

| Yes | 43 (10.1) |

| Survivors’ stroke impactc | |

| Motor | 301 (99.0) |

| Bowel and bladder | 169 (55.8) |

| Cognitive | 259 (85.5 |

| Emotional | 241 (79.5) |

| Pain | 102 (33.7) |

- Note: Total does not add 443 in all variables due to missing data.

- aParents, siblings, grandchildren, sons-in-law, sisters-in-law, and stepdaughters.

- bInformal caregivers that provide care to more than one care recipient (not necessarily stroke survivor).

- cBased on poststroke checklist [36].

3.2. Life Changes and Learning Processes of Informal Caregivers of Stroke Survivors

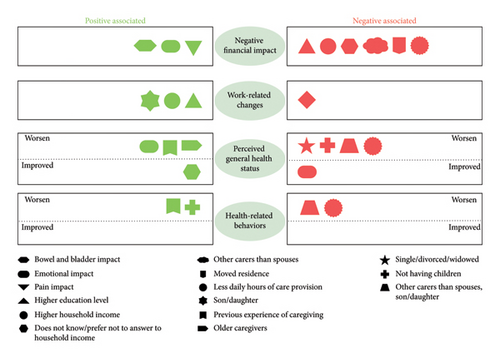

Figure 1 illustrates the quantitative results (present on Table 2), namely, the factors associated with negative financial impact, work-related changes, perceived general health status, and health related changes, highlighting both positive and negative associations. Several variables consistently appear across different outcomes and in the same direction, suggesting robust patterns. For instance, emotional impact on stroke survivors and previous experience of caregiving are positive associated with different outcomes such as negative financial impact and perceived general health status and perceived general health status and HRB, respectively. Conversely, less daily hours of care provision and having other relationship with survivor rather than spouses or son/daughter are more frequently linked with negative outcomes. Overall, the figure highlights the complexity of caregiving experiences, with certain characteristics acting as either risk or protective factors depending on the specific dimension of impact considered.

| Sociodemographic characteristics | Negative financial impact∗ | Work-related changes∗∗ | Perceived general health status | Health-related behaviors | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | Worsen1 (n = 241) OR (95% IC) | Improved2 (n = 12) OR (95% IC) | Worsen3 (n = 285) OR (95% IC) | Improved4 (n = 44) OR (95% IC) | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Male | 1.38 (0.77–2.49) | 1.92 (0.77–4.79) | 0.65 (0.37–1.15) | 0.49 (0.60–3.95) | 0.73 (0.39–1.41) | 1.56 (0.63–3.85) |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| < 65 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ≥ 65 | 1.18 (0.78–1.79) | 0.41 (0.16–1.01) | 1.95 (1.26–3.02) | 0.69 (0.15–3.28) | 1.13 (0.71–1.83) | 0.62 (0.27–1.44) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married/cohabiting | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Single/divorced/widowed | 1.0 (0.61–1.60) | 1.09 (0.64–1.86) | 0.55 (0.34–0.88) | 0.58 (0.12–2.74) | 1.27 (0.72–1.22) | 0.88 (0.34–2.25) |

| Educational level (years) | ||||||

| ≤ 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5–9 | 0.71 (0.45–1.12) | 1.77 (0.99–3.17) | 0.80 (0.51–1.27) | 2.42 (0.58–10.1) | 0.84 (0.50–1.39) | 0.67 (0.28–1.57) |

| 10–12 | 0.33 (0.18–0.59) | 2.11 (1.05–4.22) | 0.63 (0.36–1.12) | 0.74 (0.74–7.42) | 0.74 (0.39–1.40) | 0.47 (0.14–1.57) |

| > 12 | 0.32 (0.17–0.62) | 3.78 (1.68–8.49) | 0.71 (0.37–1.36) | 2.19 (0.34–14.0) | 1.17 (0.51–2.66) | 2.63 (0.92–1.57) |

| Household income (€/month) | ||||||

| ≤ 1000 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| > 1000 | 0.30 (0.19–0.46) | 1.60 (1.00–2.67) | 0.96 (0.63–1.47) | 0.86 (0.15–4.82) | 0.97 (0.59–1.59) | 0.91 (0.42–1.99) |

| Does not know/prefer not to answer | 0.40 (0.22–0.73) | 0.88 (0.43–1.83) | 1.30 (0.70–2.41) | 7.98 (2.05–30.97) | 0.59 (0.32–1.09) | 0.42 (0.13–1.36) |

| Neighborhood | ||||||

| Rural | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Urban | 1.14 (0.77–1.66) | 0.58 (0.36–0.92) | 1.03 (0.70–1.52) | 0.46 (0.13–1.59) | 1.27 (0.82–1.97) | 1.34 (0.66–2.69) |

| Children | ||||||

| Yes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| No | 0.66 (0.39–1.11) | 1.06 (0.59–1.92) | 0.42 (0.25–0.72) | 0.316 (0.40–2.52) | 2.03 (1.02–4.05) | 1.46 (0.51–4.23) |

| Caregiving-related characteristics | ||||||

| Relationship | ||||||

| Spouse | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Son/daughter | 0.40 (0.25–0.61) | 1.97 (1.09–3.56) | 0.68 (0.44–1.05) | 0.61 (0.17–2.19) | 0.85 (0.52–1.40) | 0.50 (0.23–1.07) |

| Othera | 0.34 (0.19–0.61) | 1.27 (0.60–2.67) | 0.43 (0.24–0.78) | 0.60 (0.11–3.26) | 0.50 (0.27–0.96) | 1.65 (0.77–3.52) |

| Residence | ||||||

| Without changes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Moved into survivor’s house/new residence | 0.58 (0.37–0.90) | 1.39 (0.84–2.29) | 0.87 (0.55–1.36) | 2.96 (0.91–9.63) | 0.96 (0.58–1.61) | 1.65 (0.77–3.52) |

| Hours of care provision/day | ||||||

| ≥ 8 h | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | 1 | 1 |

| < 8 h | 0.44 (0.26–0.75) | 0.93 (0.52–1.67) | 0.58 (0.34–0.98) | — | 0.45 (0.25–0.79) | 0.91 (0.38–2.13) |

| Previous experience of informal caregiving | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.19 (0.79–1.81) | 0.79 (0.48–1.30) | 1.82 (1.18–2.81) | 0.65 (0.14–3.1) | 1.82 (1.09–3.02) | 1.32 (0.59–2.93) |

| Multiple informal caregiverb | ||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.47 (0.75–2.88) | 0.93 (0.46–1.88) | 1.17 (0.60–2.25) | 0.98 (0.12–8.12) | 1.19 (0.56–2.53) | 0.77 (0.20–2.97) |

| Survivors stroke impactc | ||||||

| Motor | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | 1 | — |

| 2.77 (0.25–30.86) | 1.94 (0.72–1.24) | 0.79 (0.71–8.79) | — | 5.22 (0.47–58.49) | — | |

| Bowel and bladder | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1.97 (1.23–3.13) | 2.20 (1.26–3.85) | 1.58 (1.00–2.54) | 1.58 (0.42–5.91) | 1.26 (0.74–2.14) | 0.50 (0.21–1.18) | |

| Cognitive | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1.01 (0.52–1.94) | 1.34 (0.62–2.90) | 1.52 (0.79–2.93) | 0.85 (0.17–4.31) | 1.24 (0.61–2.56) | 1.3 (0.39–4.36) | |

| Emotional | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2.91 (1.63–5.19) | 0.85 (0.44–1.64) | 1.82 (1.01–3.28) | 0.22 (0.58–0.84) | 1.76 (0.94–3.27) | 1.16 (0.43–3.11) | |

| Pain | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1.69 (1.03–2.79) | 1.28 (0.72–2.28) | 1.50 (0.90–2.50) | 1.08 (0.26–4.46) | 1.51 (0.84–2.70) | 1.12 (0.44–2.84) | |

- Note: Odds ratio was not calculated if there were no cases. All statistically significant associations are highlighted in bold to emphasize key findings.

- aParents, siblings, grandchildren, sons-in-law, sisters-in-law, and stepdaughters.

- bInformal caregivers that provide care to more than one care recipient (not necessarily stroke survivor).

- cBased on poststroke checklist [36].

- ∗The stroke caused changes/economic problems in the family.

- ∗∗Informal caregivers who suspended work, retired, or left their jobs (n = 138).

- 1Much worse/a little worse vs. about the same.

- 2Somewhat better/much better vs. about the same.

- 3It was considered when three or more of the following health-related behaviors worsened: tobacco consumption, alcohol consumption, dietary habits, physical exercise, and sleep quality.

- 4It was considered when three or more of the following health-related behaviors improved: tobacco consumption, alcohol consumption, dietary habits, physical exercise, and sleep quality.

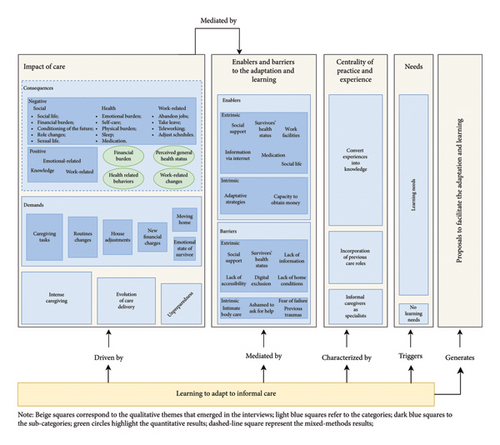

Figure 2 presents an integrated overview of the quantitative and qualitative findings, illustrating how both data strands were merged to provide a comprehensive understanding of the study results. Five themes emerged in qualitative analysis: (1) disruption and impact: the informal care as a formative context; (2) enablers and barriers to the adaptation and learning; (3) the centrality of practice and experience; (4) experiential learning as a driver for change; and (5) learning needs. Quantitative data were merged into the impact of care theme, specifically in the category related to the consequences of assuming this role. This figure evidence that the learning processes are driven by the impact that care assumes on the lives of caregivers. Enablers and barriers mediate this impact and the learning processes. The practice and experience characterized the learning after assuming the caregiving tasks, which triggers different needs. It was noted that being immersed in these processes of experiential adaptation generates proposals to facilitate the learning and adaptation of informal caregivers.

3.2.1. Impact of Care

All the informal caregivers interviewed highlighted that the stroke brought structural changes to their lives that triggered the need for adaptation and learning. Faced with unknown situations and the breakdown of automatisms, informal caregivers had to deal with (negative and positive) consequences and new demands, which required restructuring of routines and consequent learning.

“I lost my life, didn’t I? I can’t do anything without her, for example, I can’t go out to dinner (…) that my mother freaks out, in other words, came to [the caregiving role] condition me in every way, I can’t do anything without her consent.” (I06, daughter, 24 y)

“I stopped earning money, I was left with just his retirement pension, it’s small too (…) that was what affected me the most because before (…) I had money in my wallet, I would earn more, not now (…) I have to manage it better because getting from one month to the next is difficult.” (I04, spouse, 65 y).

Regarding financial burden, the quantitative results showed that informal caregivers with more than 10 years of education (10–12 years: OR, 0.33 and 95% CI, 0.18–0.59 and > 12 years: OR, 0.32 and 95% CI, 0.17–0.62), who reported a higher income (OR, 0.30 and 95% CI, 0.19–0.46) or those who do not know/prefer not to answer (OR, 0.40 and 95% CI, 0.22–0.73), who are son/daughter (OR, 0.40 and 95% CI, 0.25–0.61) or have other relationship with the survivor (OR, 0.34 and 95% CI, 0.19–0.61), who have moved into survivor’s house/or to a new residence (OR, 0.58 and 95% CI, 0.37–0.90), and who provide less than eight hours of care a day (OR, 0.44 and 95% CI, 0.26–0.75), were less likely to report having economic problems after stroke (Table 2). On the other hand, those caring for survivors who have problems in bowel and bladder (OR, 1.97 and 95% CI, 1.23–3.13), emotional (OR, 2.91 and 95% CI, 1.63–5.19), or pain (OR, 1.69 and 95% CI, 1.03–2.79) consequences seem to be more likely to experience financial burden.

Caregivers also reinforced that taking on informal care conditioned their future due to the responsibilities inherent to the new role (e.g., the impossibility of volunteering outside the country, the need to control more expensive purchases, and the obligation to move to survivors’ homes, leaving their own homes). With less expression, the participants reported that taking care of their family members reversed their roles; for instance, children take on the role of care, imposing limits, managing the home, and performing tasks generally attributed to the parents. One male caregiver reported that after the stroke no longer had sexual relations with the survivor.

“Although during the day I sit here in the armchair (…) the routine is so intense that while I’m sitting here (…) there are four things, five things to do and I have difficulty dealing with them (…) I get more nervous, more stressed.” (I08, spouse, 55 y).

The survivor-centered life led to a decrease in the time available for caregivers to engage in self-care activities (e.g., going to medical appointments, going to the hairdresser, and shopping), which negatively affected their self-esteem. The physical burden was a consequence frequently mentioned by interviewees, especially as they became the main (and sometimes only) responsible for household chores and because of the new physically demanding care tasks (e.g., mobilization, transport, dressing, and bathing), causing health problems: “on a physical level, I have already had three hernias in my spine” (I29, daughter-in-law, 52 y). Informal caregivers mentioned that taking care of their relatives affected both the duration and quality of their sleep. They also noted the need to adapt to new night-time tasks, which caused them to wake up more frequently and have less deep and restful sleep. One participant highlighted the need to start taking psychiatric medication after assuming the caregiving role to “be calmer” (I12, wife, 64 y).

Older caregivers (OR, 1.95 and 95% CI, 1.26–3.02) were more likely to report a decline in their general health (Table 2). Participants with previous experience of informal caregiving presented a higher probability of reporting a decline both in their general health and HRB (OR, 1.82 and 95% CI, 1.18–2.81 and OR, 1.82 and 95% CI, 1.09–3.02, respectively). Those who cared for survivors with emotional consequences of stroke had higher chances of reporting a decline in their health (OR, 1.82 and 95% CI, 1.01–3.28) and lower chances to report and improve their health (OR, 0.22 and 95% CI, 0.58–0.84). Single/divorced/widowed caregivers (OR, 0.55 and 95% CI, 0.34–0.88) presented higher odds of not considering a worse general health after assuming the role of caregiver. Those who do not know/prefer not to answer their household income have a higher probability of perceiving an improvement in their general health (OR, 7.98 and 95% CI, 2.05–30.97). Finally, informal caregivers with relationships other than son/daughter or spouse (OR, 0.50 and 95% CI, 0.27–0.96) and those providing < 8 h of care were less likely to perceive a worsening in their HRB (OR, 0.45 and 95% CI, 0.25–0.79). Caregivers without children (OR, 2.03 and 95% CI, 1.02–4.05) were more likely to perceive a worsening in their HRB and, conversely, were less likely to consider a worsening in their general health after assuming care (OR 0.42 and 95% CI, 0.25–0.72) (Table 2).

Informal caregivers also highlighted positive consequences, namely, emotional-related consequences, the acquisition of knowledge, and work-related changes. Taking care of the survivors brought them emotional growth (e.g., being more patient, seeing life from another perspective, or more maturity in conflict management); strengthened their relationships, since there is greater proximity, joint growth, more affection, and sharing; brought them positive emotions (feelings of gratitude and usefulness, joy, pride, and peace); and increased their self-esteem, especially because they feel more capable and confident about the role of caring. The following excerpt illustrates this idea: “I have learned to manage my emotions (…) The positive [of being a caregiver] are my development as a human being, how good I feel about myself for caring.” (I10, daughter, 47 y).

“It was positive because I didn’t have knowledge about certain issues, I ’didn’t even know what a caregiver was (…) now I have the knowledge, a lot of knowledge (…) I learned things that I was not aware of” (I12, spouse, 64 y).

The demands were identified as another dimension that sparked new learning and adaptations. The caregiving tasks were central in the processes of being an informal caregiver and appeared to require structural adaptations in family life, translated into experiential learning processes that accompanied caregivers in the short, medium, and long term, as stated: “My life completely stopped because (…) [I have to] bath my wife, change diapers (…) all of those are things that I never imagined doing in my life.” (I32, husband, 67 y)

The routine changes also emerged as a demand. Assuming the caregiving role required life changes and the reorganization of caregivers’ days, according to the new needs of survivors: “Everything is routine, everything that is habit ends up being changed. Of course, throughout the time we needed to adjust (…), there were a series of limitations. I had to make a radical change to my lifestyle.” (I26, grandson, 31 y)

“I had to put non-slip rugs, most of them I removed (…) I had to get lamps that light up when you move (…) on the bathroom I needed to buy poles to support him (…) these are the little things that we need to adapt.” (I14, spouse, 61 y)

New financial charges arrived after starting care, especially due to the costs associated with the survivor’s medication. Despite the house arrangements being more frequent demands, caregivers highlighted that they had to move home due to the new conditions of survivors. One informal caregiver affirmed that managing the emotional state of the stroke survivor was a demand after assuming the unexpected role.

Faced with these consequences and demands, caregivers seemed to highlight three categories (intensive caregiving, evolution of care delivery, and feelings of unpreparedness) that functioned as mediators for the learning processes. In other words, these categories seem to influence how consequences and demands are perceived and, consequently, managed with adaptation and learning mechanisms.

“At the beginning, mobility was completely different, you didn’t have to make half of the effort (…) [now] It′s getting very complicated (…), and I’m always learning because it’s getting worse (…) Now I’ve adapted, the first few days were difficult.” (I17, daughter, 52 y).

Conversely, another caregiver stated, “When he came from the hospital, he came with a nasogastric tube, but he improved a lot. Then, he did physiotherapy, did everything. I am not here 24 h, I spent the first few months sleeping (in the same house as the survivor), and now I am just giving the medication, bathing, that is it” (I38, daughter, 48 y).

Some participants reinforced that when assuming the unexpected role, feelings of unpreparedness emerged. Since being a caregiver was a distant and unlikely reality for the participants, they reported that they did not have access to sufficient information and training to prepare them for the new and demanding tasks (e.g., managing and administrating medication, bathing, and changing diapers).

3.2.2. Enablers and Barriers to the Adaptation and Learning

Regarding the extrinsic enablers, participants frequently reported the existence and importance of social support (informal and formal). For caregivers, having family members, friends and neighbours who support them throughout the care trajectory was crucial and support from peers. As illustrated, “I also have very good family support (…) great support, a very good family background, and that is a great help.” (I07, daughter, 43 y). Concerning formal support, they mentioned the importance of healthcare services, the training support from professionals, and the existence of practical support, namely, the provision of care equipment and products (e.g., urine bags, diapers, beds, wheelchairs), housekeeping, and transportation.

“The girls [nurses and health care assistants] from the institution where he was there for three months, undergoing physiotherapy, (…) gave me a little guidance (…) it helps me a lot because I was really ‘blind’ (…) they explained to me how I should handle it, how I shouldn’t.” (I12, spouse, 64 y)

In addition, some caregivers mentioned the survivor’s health status (especially the level of functionality and emotional state), the existence of flexible working conditions, the provision of information via the Internet, maintaining a social life, and the use of medication as enablers.

“Taking care of my wife, it’s a duty I have to take care of her, so she would also have to take care of me. We’ve been married for 52 years (…) in good times and in bad times, we’ve always been at each other’s side.” (I23, husband, 77 y)

Less expressively, informal caregivers used active search for information, escape-avoidance approaches, promotion of leisure activities, reliance on bonds of affection, religious-based strategies, and retribution. Strategies such as being authoritative, crying, use of medication, using humor, and having patience emerged. In addition to the adaptative strategies, one caregiver reported that the capacity to obtain money carrying out small extra jobs facilitated their life after assuming the caregiver role.

The lack of information about stroke, the care, and how to access support were also reinforced as barriers: “If exists [social support] we are the ones who have to find out if it exists because we have no information (…) because we are not informed (…) there is no knowledge, there is no disclosure of anything.” (I18, daughter-in-law, 47 y). The survivor’s health status also seems to have functioned as a barrier to the adaptation and learning of caregivers, namely, the emotional and physical state of survivors affected the care provided, increasing its demands, with consequences for the well-being of caregivers. With less expression, lack of accessibility (in public transports and inadequate conditions of pavements), digital exclusion, and lack of home conditions also emerged as barriers.

Intrinsic barriers were rarely mentioned with some interviews reporting the embarrassment of caring for the survivor’s body, the existence of previous emotional traumas, the shame to ask for help, and the fear of failure.

3.2.3. The Centrality of Practice and Experience

“Then you realize that the way of taking shower doesn’t work (…) you realize that some food makes him go to the bathroom less frequently, so you start to learn (…) in my case was an evolution (…) because we started to gather tools for this and we created a routine, we organized ourselves.” (I08, spouse, 55 y)

“It wasn’t new anymore because when it happened to my mother, my father had already had two strokes (…) This was no longer new to me because I already had baggage (…) he also had it at home and needed more care.” (I06, daughter, 24 y)

“I took magnesium and gave her magnesium, she was so tired, to see if it would at least whet her appetite, on a self-initiative basis (…) I have learned so much that I have already said that I will go into medicine school next [laughs] (…) dealing with medication, I’m now a medication expert, sometimes [I say] ‘Oh, my daughter, that’s many years of experience, we learn a lot.’” (I07, daughter, 43 y)

3.2.4. Proposals to Facilitate the Adaptation and Learning

Considering informal caregivers’ trajectory, main barriers and enablers, and resulting experiential learning, they often concluded their interviews stressing the need to invest in the informal caregiving sector and propose measures for improving wellbeing. In general, it was noted that due to the participant’s experience, they had a participatory and reflective stance regarding their rights. Specifically, they drew attention to the need for care-related support, namely, domiciliary care, proximity services, flexibility at work, informal caregivers’ associations, psychological support, care equipment and products (e.g., medication and diapers), transportation, and support measures that allow caregivers to rest conditions to rest. In addition, participants suggested that public services must disseminate relevant resources, particularly regarding dissemination of information on access to support and stroke. Helping families with economic aid was also a recommendation. Finally, interviewees reinforced the need for laws aimed at informal caregivers that are strictly enforced: “[We need] the laws that exist to be put into practice” (I08, spouse, 55 y).

3.2.5. Learning Needs

“They [health professionals] should provide training, that would have to go through someone who came to help a caregiver during the early stages (…) Because we had to learn it ourselves. (…) Training will have to be more practical. (…) It would be a person who (…) transmitting with his experience, explain to us how to do it.” (I16, son in law, 67 y)

Although the caregivers’ speeches indicated that learning processes happen spontaneously and, on a trial-and-error basis, they specified the need for support of these processes. They considered that professionals should facilitate these processes using a logic of proximity, horizontality, and understandable examples. The professional knowledge, acquired through formal education models, is understood as a support for caregivers’ experiential and situated knowledge. On the other hand, some caregivers stated, “I did not learn much” (I36, daughter, 56 y), showing that there was no identification of learning processes underlying becoming or being an informal caregiver.

4. Discussion

Our mixed methods’ study provided a comprehensive understanding of the complex nature of adaptation and learning in caregiving. Integrating qualitative and quantitative data allowed us to capture the dynamic, impactful, and multifaceted nature of becoming an informal caregiver, highlighting the intricate interactions between individual and social spheres in unpredictable contexts. The findings further support the conceptualization of informal care as a learning process and context, where cognitive abilities, intentions, and situational demands interact. In practice, previous knowledge structures are reshaped to assimilate the new reality, influenced by individual and social circumstances. Figure 1 visually encapsulates the adaptation and learning process in informal care, illustrating how it is driven by the impact of care—including its demands and consequences—mediated by enablers and barriers and shaped by caregivers’ experiential engagement. It highlights the centrality of practice in transforming experiences into knowledge and the role of prior care experiences. In addition, it points to learning needs and outlines proposals to facilitate caregivers’ adaptation and learning, emphasizing this process’s dynamic and multidimensional nature.

This study reinforces the importance of preparing caregivers for unexpected structural changes and providing social, health, and educational resources to reduce the overload attributed to this role. Thus, developing social policies and proximity services that promote informal networks to support caregivers and buffering the negative impact of care could be beneficial. Strengthening familial and peer networks [37, 38] and community-based services and interventions can improve the perceived social support, transforming it into a coping resource and reducing stress and burden on caregivers’ health outcomes [39, 40]. In addition, promoting caregivers’ engagement in leisure and social activities can prevent loneliness and social exclusion [41–46]. Care-friendly societies that offer supportive services on an ongoing basis can promote the sustainability of the caregiving situation, which is particularly important to prevent potential health and social long-term consequences of care [47].

In line with previous studies, different financial stressors emerged when assuming the caregiver’s role: monthly income variation and new private costs (e.g., additional grocery bills, transportation costs, healthcare charges, and medical supplies costs) [48]. Those who have greater difficulty buffering these difficulties, namely, caregivers with lower education levels, lower income, providing a greater number of hours of care, who had to change their family dynamics (e.g., moving house), and who care for people with difficulties that require specific care material, namely, diapers to contain bowel or bladder difficulties, may have to deal with financial fragility. Financial fragility/stress can impact the health of individuals (e.g., increase sleep deprivation and depressive symptoms), reduce the quality of care provided, increase social isolation, and compromise wellbeing [48, 49]. Since an income-reducing effect is expected after assuming informal caregiving tasks, public policies need to improve financial security, particularly for high socioeconomic disadvantage caregivers, as well as to promote adequate labor market conditions (e.g., flexible work arrangements and employment opportunities), financial counseling and literacy, and access to financial services (e.g., loans) [48] should also be considered.

Health is a crucial and fundamental dimension to consider when discussing issues related to informal care [50]. Our study highlights the relationship between socioeconomic and caregiving-related characteristics and caregivers’ health perceptions and behaviors. It emphasizes the importance of developing support strategies for caregivers designed according to their characteristics, promoting health among people in vulnerable situations. The emotional burden reinforced by caregivers stands out the importance of developing long-term interventions that improve stress-coping skills to mitigate depressive and anxiety symptoms, psychological distress, and negative feelings related to care, such as shame and feelings of failure. The development of problem-focused strategies appears as intrinsic adaptative strategies; thus, psychosocial interventions tailored to caregivers, aimed at equipping them with positive coping mechanisms, may mitigate psychological distress and actively support learning and adaptation processes. Positive psychological constructs (e.g., resilience and self-efficacy) may contribute to informal caregivers’ adaptation, extending beyond the absence of anxiety and depression symptoms [51]. These constructs may actively foster confidence, emotional regulation, and problem-solving abilities [52], enabling caregivers to navigate challenges more effectively. By strengthening their capacity to manage caregiving demands, they not only enhance their wellbeing but also contribute to better care quality for stroke survivors.

Personal self-care is strongly associated with emotional wellbeing, pain, perceived stress, and general health [53]. The intensive nature of caregiving often centers adaptation and learning on maintaining the person cared for, with little awareness of the need for self-care and maintaining the wellbeing of caregivers. Improving care coordination (between caregivers and support services) can promote the caregivers’ support and role relief, potentiating outside activities and self-care behaviors. In addition, providing accessible self-care interventions (e.g., directed to self-management, self-testing, and self-awareness) could also benefit caregivers’ health outcomes [54–56].

Caregivers had to learn how to deal with the physical demands of care. The demanding nature of caregiving tasks leads to significant physical strain, manifesting as musculoskeletal problems, chronic pain, and fatigue [57]. To mitigate these effects, it is recommended that caregivers receive training on proper body mechanics and lifting techniques, have access to assistive devices, and be encouraged to take regular breaks and engage in physical activity [25, 58] to maintain their health. Support groups and respite care services can also provide essential relief and prevent burnout. Moreover, given the interdependence between the health of survivors and the need for care, it is important to include stroke survivors’ recovery in a long-term care approach, promoting their physical and mental wellbeing.

The commonly reported sleep deprivation and its consequences on the health of caregivers call for interventions that guarantee rest and sleep quality [59]. It will be useful political measures that ensure daily practical support for caregivers so that they can rest, among health education materials to promote sleep hygiene and facilitate the search for social or medical support. The use of medication was frequently present in the caregivers’ discourses. In general, taking medication helps to manage the new overwhelming situation. For some, the medication intake was a negative consequence of care; for others, it was an enabler of adaptation. These results point to the need to look beyond the medicalization of care, acting in a preventive way (particularly concerning mental illness) by providing healthier, less invasive, and less expensive tools (both for individuals and for health care systems). In addition, due to the tendency of polypharmacy in people cared for and the medication management requirements [60, 61], it is important to increase health literacy about this subject to avoid inadequate medication management and reduce the risks of drug interactions, reactions, and cognitive impairments [61]. Moreover, ensuring educative support that promotes awareness about medication management will help caregivers to better deal with the drug therapy of survivors.

Some caregivers experienced conflicts between informal care and paid work, especially due to the demands of full-time care. Consequently, they need or want to adapt their professional status to better combine care and work [62]. The long-lasting consequences of adapting paid work have already been studied, drawing attention to the need for policies and practices that reduce social and labor market inequalities and focusing on difficulties in professional reintegration, reduced wages, or lower pension entitlements [61, 63, 64]. Our results also showed another side of professional changes that is still little studied, the positive consequences of ceasing/reducing working hours. In countries where working lives are prolonged, and social policies retain seniors in the labor force [65, 66], more people are reaching the point where they must take care of their family members and manage work responsibilities. Hence, the cessation of work can mean a significant reduction in daily burden, and maintenance of time spent on other nonmarket activities (e.g., hobbies), improving the caregivers’ perception of wellbeing. The quantitative results indicated that those with a more comfortable social and professional situation changed their work state more frequently. These results may indicate the need to look at social and economic policies that force people, especially those in vulnerable situations, to maintain professional activity and care, thanks to the lack of economic support for informal caregivers.

Despite the exhaustive nature of the care role, positive consequences stand out among caregivers. Personal satisfaction, emotional growth, improved relationship with the care recipient, gaining spiritual/religious blessings, or learning new skills are consequences rarely emphasized in the literature [67, 68]. The field of informal care could benefit from research and practices that not only attenuate the negative consequences of caregiving but also actively promote the positive effects of these experiences. This study contributes to a broader understanding of the role of positive psychological constructs in the adaptation and learning processes of informal caregiving. It reinforces the idea that these constructs should be considered not only as consequences of caregiving—alongside its challenges—but also as potential mediators that may shape how caregivers navigate and adjust to their role. Their presence does not necessarily indicate the absence of depression or anxiety; rather, they can act as protective factors that help caregivers cope with stress, regulate emotions, and develop problem-solving strategies. By fostering these psychological resources, caregivers may experience reduced psychological distress and greater overall wellbeing. Recognizing this dual role—both as consequences of caregiving and as potential mediators of adaptation—underscores the need for interventions that actively cultivate positive states, traits, and relationships [69] to support caregivers in sustaining their role while minimizing emotional burden.

Feelings of unpreparedness stemmed from a lack of information and training, underscoring the need for better preparation and support for caregivers [70–72]. It is important to recognize the experiential knowledge of these unpaid workers and, at the same time, to professionally support them, reducing risks for the caregivers and stroke survivors. To this end, proximity services that promote horizontality and move away from formal and nonsignificant educational processes are necessary.

Informal caregivers demonstrated that being immersed in care experiences triggers learning, noticeable, e.g., in the appropriation of technical terms and procedures, making informal caregivers “experts”. When faced with the new reality, especially due to the demands related to ADLS, caregivers relied primarily on experiential and informal learning processes to cope with the new reality. They use previous knowledge (e.g., related to care experiences), reformulate some, or create new ones, on a trial-and-error basis, until they become “experts” in the field. This interactive process aligns with Kolb’s experiential learning cycle, where caregivers engage in concrete experience when confronted with unfamiliar caregiving tasks, move through reflective observation by assessing what strategies work or fail, develop abstract conceptualization as they refine and internalize caregiving techniques, and apply this knowledge through active experimentation in their daily routines [73]. This result highlights the need to look beyond the hegemony of knowledge acquired through formal models and recognize informal knowledge. As previously explored, activities that place the subject in interaction with themselves, others, and the surrounding environment generate learning [16, 21]. This experiential learning can be seen as valuable insights that should be recognized and integrated into public strategies for caregiver support [74]. Furthermore, it underscores the significance of including these individuals in decision-making processes and the formulation of support measures, which are crucial for developing context-specific policies. This approach can promote active participation and citizenship, fostering a more inclusive and responsive caregiving ecosystem.

The expertise developed by informal caregivers supports the argument that knowledge is inherently embedded in lived experiences and shaped by contextual interactions, occurring beyond the scope of formal education models. Theoretical contributions from transformative learning and situated cognition theories may provide a valuable framework for understanding this argument. In the context of adult education and the increasing complexity of contemporary societal and educational challenges, recognizing diverse learning pathways is essential and framing them within a critical thinking model can be crucial. From a transformative learning perspective [75], the learning process begins when informal caregivers undergo disorienting dilemmas when faced with the unexpected demands of caregiving, such as administering medication or managing daily care routines. This triggers critical reflection, prompting them to reassess their assumptions, acquire new knowledge, and develop adaptive strategies. Consequently, this process impacts their role over time, as they move from feeling unprepared to recognizing themselves as competent and knowledgeable caregivers.

Regarding situated cognition, this study clearly argued that becoming an informal caregiver is a situated learning process bounded to social, cultural and physical contexts [76]. Knowledge and learning mainly appear as a product of the caregiving activity, and experiences, deeply embedded in real-world contexts, skills, and problem-solving strategies. Informal caregivers acquire expertise through hands-on experience, interacting with healthcare professionals, observing practices, recovering previous care practices, and refining their skills through trial and error. This situated nature of learning ensures that knowledge directly applies to their caregiving routines. This study shows that caregivers’ expertise is not merely a collection of skills but a dynamic, context-driven learning process that reshapes both their capabilities and perceptions of themselves. Acknowledging these learning processes highlights the need for more equitable conditions and contexts supporting informal caregivers’ adaptation to care. Ensuring access to appropriate resources, guidance, and social support can mitigate the burden of informal caregiving and foster more meaningful learning experiences. By recognizing caregiving as a legitimate and complex learning process, policies and interventions can be designed to promote more just and inclusive conditions, reducing asymmetries between different caregiver groups and enhancing their overall wellbeing.

The provision of information was included in different themes of this work (enablers, barriers, and proposals), highlighting its centrality. The results suggested the need for information on stroke and care delivery through diverse and accessible channels (e.g., the Internet) and guidance on accessing formal support. Studies on care needs often reported inadequate information and resources, namely, received information on stroke management and recovery and/or how to contact a healthcare professional or search for psychological/emotional support, with consequences on informal caregivers’ burden, depression, and anxiety [77–79]. Thus, to ensure their health and wellbeing, as well as the people that they care for, it is crucial to address these needs in policies and services. Also, a previous study on the Status of Portuguese Informal Caregivers (which regulates the rights and duties of these groups) alerts us to the lack of knowledge about support measures and services [63]. To hamper the potential inequalities in the field of care and empower caregivers is essential to develop strategies that promote literacy and civic awareness. In line with previous studies, this research highlights the centrality of the state in assisting and supporting caregivers, calling for a change in the paradigm of European health systems towards care and family-centered policies [80]. Nowadays, social care privileges financial compensations with scarce investment in other types of assistance (e.g., information provision, special legal, or work statuses), which can hamper the responses to the complexity of care provision, increasing the burden of care [81].

Our findings indicate that some caregivers do not identify the learning processes underlying the care role. This may indicate that informal care continues to be naturalized and seen as a moral obligation within the framework of family responsibility, and care as help, based on reciprocity [82], denying the needs and rights that this role entails. This reality hampers the visibility of this unpaid and female-dominated work and points out the importance of developing measures focused on social transformation and empowerment of informal caregivers [83].

4.1. Limitations

This is a regional-based study with a high participation rate, and its mixed methods’ design allowed for a deep understanding of the research problem by integrating qualitative and quantitative dimensions, which would not have been possible with a purely quantitative approach (as shown in Figure 2); however, some limitations should be discussed. First, the discrepancy in time in which the quantitative study—inserted in a larger study—was designed and the design of the research questions of this specific study, meant that the assessment of adaptation and learning and its construct was dependent on the variables already included. However, the qualitative data collection was sensitive to dimensions potentially not assessed by the structured questionnaire, allowing the collection of richer data to answer the research question.

A major strength of this study is its representativeness, as it includes multicentric data from the entire northern region of Portugal, with a high participation rate of nearly 82%. However, the sample of 443 informal caregivers may still limit the generalizability of the findings. Despite the statistical significance of the results, the presence of unidentified confounders cannot be ruled out. In addition, smaller sample sizes have lower power to detect true effects, which may increase the likelihood of overestimating effect sizes [84]. Nevertheless, the validity and utility of studies with small samples should not be dismissed lightly [85]. Therefore, while acknowledging these limitations, these study findings provide meaningful associations that warrant further investigation in future studies with larger, more representative, and multicentric samples.

In addition, the 12–18 months’ time gap between quantitative and qualitative data collection presents a potential limitation due to recall bias, as participants’ memories may be influenced by the time elapsed. While long-term studies on caregivers’ experiences, particularly those extending beyond 1 year after a stroke, are scarce, this study was designed to capture both immediate and evolving adaptation and learning processes. The extended time frame allowed participants to reflect on their experiences with a greater perspective, highlighting key moments of adaptation and learning. Although recall bias could affect retrospective data, strategies to mitigate its impact were considered. First, the interview was not directly focused on the quantitative questionnaire but on the caregivers’ reflections on their journey. Participants were temporally situated by asking them to compare their caregiving experience from the beginning to the present and identify the most relevant experiences. Moreover, informal caregiving is a highly significant experience for these individuals, and their vivid memories of both the beginning and the ongoing process further reduce the risk of substantial recall bias. Finally, the triangulation of quantitative data, collected closer to the initial caregiving period, with qualitative narratives helped strengthen the validity of our findings and minimized potential distortions.

The reflexivity bias should also be acknowledged. Given the authors’ prior knowledge and academic background in informal caregiving, potential biases may have emerged, such as assumptions regarding caregiver burden and the challenges associated with informal care. To mitigate these biases, the authors critically examined the theoretical and epistemological assumptions and their potential influence on analysis. This was achieved through iterative discussions within the research team, memo writing in Nvivo software to document analytic decisions throughout the data analysis process and revisiting the data to ensure that interpretations remained grounded in participants’ narratives rather than preconceived notions. While reflexivity strengthens the credibility of the findings, it should be recognized that alternative interpretations may exist, and future research could further explore these perspectives through different methodological and analytical approaches.

The selection bias is also a potential limitation in this study, as participants were not randomly selected for the qualitative study; however, purposive sampling was used to ensure heterogeneity and diverse representation across key demographic and caregiving characteristics. Another potential limitation is that the paper presents crude OR. Although sensitivity analyses were conducted and models adjusted for sex and age (data not shown), these results were not included to maintain the descriptive focus of the study. Nonetheless, the direction and consistency of the associations remained unchanged, supporting the robustness of the findings.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, most of the questionnaires and interviews were collected by telephone, which may have excluded some participants who are not competent and/or feel comfortable using telephones and those with impaired cognitive skills that impact their ability to express themselves. However, telephone interviews are a useful and widespread data collection method among this population. They represent a valid and reliable method for assessing both functional and cognitive outcomes, even when assessing sensible data [86], in this after-stroke setting. The risk of social-desirability bias may exist since self-reported data was collected. Nevertheless, these are frequent data collection methods described in the literature [87], and the instruments used are valid and reliable methods for assessing the study’s outcomes.

5. Conclusion

This work calls on the importance of developing public policies and community services that understand and address the complexity of the care processes and provide resources to families, meeting their needs and rights to guarantee healthy, efficient, and sustainable informal care networks. In addition, this study highlights that the care experience has learning potential and should be considered to sustain more tailored, effective, and equity health education strategies directed to informal caregivers and their adaptation processes, reducing the burden of this role. Developing care-centered policies and services that contribute to the visibility of knowledge, practices, and memory, as well as promoting the ecology of care, is needed to promote positive outcomes in caregiving contexts. Framing informal care through health, social, and educational lenses could be a useful tool in designing and promoting community strategies that favor more inclusive and integrative contexts of informal care. Further studies should consider informal care as a heterogeneous process that influences and is influenced by health, social, and educational conditions to determine situations of vulnerability and exposure to different types of threats, reducing informal care burden, as well as promoting solidarity, democratic participation, and active citizenship.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This work was cofunded by the European Union, through the European Social Fund, and by national funds, through the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT), under the doctoral research grant no. 2020.07312.BD (to Ana Moura). It was also cofunded by the FCT, the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), the European Social Fund (ESF), Portugal 2020, and the European Structural and Investment Funds, through the Regional Operational Programme Norte (Norte 2020), under the project POCI-01-0145-FEDER-031898. This work was supported as well by the FCT under the multiyear funding awarded to CIIE (grant nos. UIDB/00167/2020 and UIDP/00167/2020). The authors also acknowledge the support from the Operational Programme Competitiveness and Internationalization (COMPETE 2020), Portugal 2020, European Regional Development Fund, under the Unidade de Investigação em Epidemiologia—Instituto de Saúde Pública da Universidade do Porto (EPIUnit) (POCI-01-045-FEDER-016867; Ref. FCT UID/DTP/04750/2019); and the FCT through the projects (grants nos. UIDB/04750/2020 and LA/P/0064/2020—DOI identifiers https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/04750/2020 and https://doi.org/10.54499/LA/P/0064/2020).

Acknowledgments

We thank all the professionals of the 12 Stroke Units of the ARS-Norte, the researchers who collected data, and, especially, all the informal caregivers of stroke survivors for participating in this study.

Endnotes

1CARESS—Psychological health of carers of stroke survivors: experiences, needs, and quality of life (POCI-01-0145-FEDER-031898).

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data from this study are not available to share.