Lower Functional Status, Higher Comorbidity Burden, and Higher Levels of Stress Are Associated With Worse Joint Evening Fatigue and Depressive Symptom Profiles in Outpatients Receiving Chemotherapy

Abstract

Significance: Evening fatigue and depressive symptoms are associated with several negative outcomes for patients with cancer. However, the contribution of BOTH fatigue and depressive symptoms to patient outcomes remains unknown. This study identified subgroups of patients with distinct joint evening fatigue AND depressive symptom profiles and evaluated for differences in demographic and clinical characteristics, levels of stress (i.e., global, cancer-specific, and cumulative life) and resilience, and the severity of common symptoms.

Methods: Outpatients (n = 1334) completed the Lee Fatigue Scale and Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale six times over two cycles of chemotherapy. Demographic and clinical characteristics, stress and resilience, and other common symptoms were assessed at enrollment. Joint evening fatigue and depressive symptom profiles were identified using latent profile analysis. Profile differences were assessed using parametric and nonparametric tests.

Results: Five profiles were identified (i.e., Low Evening Fatigue and Low Depression [Both Low: 20.0%], Moderate Evening Fatigue and Low Depression [Moderate Fatigue and Low Depression: 39.3%], Increasing and Decreasing Evening Fatigue and Depression [Both Increasing–Decreasing: 5.3%], Moderate Evening Fatigue and Moderate Depression [Both Moderate: 27.6%], High Evening Fatigue and High Depression [Both High: 7.8%]). Compared to the Both Low and Moderate Fatigue and Low Depression classes, the Both Moderate and Both High classes were less likely to be married, more likely to report depression, had a lower functional status, and had worse comorbidity profile. Both Moderate and Both High classes had higher levels of global, cancer-specific, and cumulative life stress and lower resilience.

Conclusions: Multiple risk factors for higher levels of evening fatigue AND depressive symptoms during chemotherapy were identified, including lower functional status, higher comorbidity burden, lower levels of resilience, and higher global, cancer-specific, and cumulative life stress. These risk factors may be used to identify patients at greatest risk for poorer outcomes and to prescribe interventions to decrease these symptoms.

1. Introduction

Fatigue associated with cancer or its treatment is a highly complex and multidimensional symptom. Described as subjective “tiredness or exhaustion” that is unrelated to activity, it encompasses physical, emotional, and/or cognitive domains [1] and is characterized by diurnal variation [2–4]. Notably, fatigue levels are positively correlated with depressive symptoms [5–12]. While fatigue is a hallmark symptom of major depressive disorder [13], fatigued patients may become depressed over time due to the negative consequences of fatigue. Both symptoms are common during cancer treatment with fatigue and clinically relevant depression occurring in 62% [14] and 27% [15] of patients, respectively. Individually, fatigue and depressive symptoms are associated with higher rates of unemployment [16, 17], as well as decrements in functional status [18–20] and quality of life [6, 21], and increased severity of other common cancer-related symptoms [22, 23]. Despite the strong evidence to suggest that these symptoms are related and have several negative outcomes, the prevalence and risk factors for BOTH fatigue and depressive symptoms in oncology patients remain unknown.

The use of patient-centered analytic approaches (e.g., latent profile analysis [LPA] and latent growth mixture modeling) to identify subgroups of patients with distinct fatigue AND depressive symptom profiles may help clarify this complexity. In addition, patient-centered approaches can be used to identify risk factors for more severe symptom experiences or trajectories.

Relatively few longitudinal studies used a patient-centered analytic approach to identify risk factors for fatigue [2–4, 24–26] or depressive symptoms [27–29] in patients receiving chemotherapy. In the two longitudinal studies that used latent growth mixture modeling to identify subgroups of breast cancer patients with distinct fatigue trajectory profiles across a cycle of chemotherapy [24, 25], three fatigue profiles were identified. In the first study [25], while no demographic or clinical differences were identified among the three classes, compared to the low fatigue class, the transient and high fatigue classes had higher depressive symptoms. In the second study [24], compared to the mild decreasing class, the high moderate decreasing class was more likely to have received doxorubicin.

In our LPAs of patients with heterogeneous cancer types that considered diurnal variations in fatigue [3, 4], four distinct morning (i.e., Very Low, Low, High, Very High) and evening (i.e., Low, Moderate, High, Very High) fatigue classes were identified across two cycles of chemotherapy. In terms of morning fatigue [4], distinct risk factors for the Very High class included higher body mass index, not being married or partnered, living alone, and having a lower annual household income. For evening fatigue, distinct risk factors for the Very High class included having childcare responsibilities, breast cancer, and high blood pressure [3]. For both morning and evening fatigue, common risk factors for the Very High classes were younger age, being female, lower functional status, higher comorbidity burden, and a self-reported diagnosis of depression. In addition, for both morning and evening fatigue, the Very High classes had significantly lower levels of morning and evening energy and attentional function and higher levels of morning and evening fatigue, trait and state anxiety, sleep disturbance, both cancer and noncancer pain, and depressive symptoms.

In terms of depressive symptoms, using latent growth mixture modeling, one study identified two depressed mood symptom trajectories (i.e., consistently mild and consistently moderate for cycle two; consistently mild and moderate improving for cycle three) over two cycles of chemotherapy in women with breast cancer [27]. Receipt of doxorubicin during cycle three was the only risk factor that was identified for the moderate improving depressive class. A second study that used latent growth mixture modeling identified four depressive symptom trajectories (i.e., low-stable, recovering, high-recovering, high-stable) from prior to 12 months after chemotherapy in women with breast cancer [28]. While no demographic or clinical risk factors were evaluated, compared to the low-stable class, the other three classes had higher physical symptom distress.

Using LPA, our team identified four distinct depressive symptom profiles (i.e., None, Subsyndromal, Moderate, and High) across two cycles of chemotherapy [29]. Compared to the None class, risk factors for the High class were not being married or partnered, living alone, and having a lower annual household income. In addition, the High class had a higher number of comorbid conditions and self-reported a diagnosis of depression. Notably, the High class had significantly lower levels of morning and evening energy and attentional function and higher trait and state anxiety, sleep disturbance, both cancer and noncancer pain, and morning and evening fatigue.

While these studies provide important information on the risk factors for fatigue or depressive symptoms, the majority of these studies were conducted among women with breast cancer [24, 25, 27, 28]. Furthermore, none of the studies provide information on fatigue AND depressive symptom joint profiles and their risk factors. This evaluation is important given that fatigue and depression may co-occur due to shared mechanisms (e.g., dysregulation of inflammatory, neuroendocrine, and/or stress pathways [30]). In the setting of a stress exposure, activation of the sympathetic nervous system results in the release of adrenaline, noradrenaline, and corticotrophin-releasing hormone [31]. In parallel and in the setting of chronic stress, repeated activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis results in glucocorticoid resistance over time [30]. Both of these processes lead to the production of proinflammatory cytokines which are associated with tumor progression [31] and sickness behavior symptoms (e.g., fatigue, depression, anxiety, and pain) [30]. Given the uncertainty and financial burden that are associated with a cancer diagnosis and its accompanying treatments, heightened stress among patients with cancer is expected. However, patients’ perceptions and responses to these stressful experiences vary due to a variety of factors, including their appraisal of the stressor(s), cumulative life stress, and resilience. Given that stress [31] and resilience [32] are modifiable, an improved understanding of how various types of stress and resilience impact the severity of evening fatigue AND depressive symptoms will inform the development of tailored interventions.

Relatively few studies have evaluated the contribution of global, cancer-specific, and cumulative life stress or resilience to the severity of fatigue [12, 33, 34] or depressive symptoms [29, 35–38] in patients receiving chemotherapy. In one study that used growth mixture modeling to identify four trajectories of cancer-specific stress over 12 months (i.e., recovery, resilience, chronic, and severely chronic) [35], compared to the resilient and recovery classes, the chronic class had higher depressive symptoms. In our LPA of evening fatigue [34], compared to the Low class, the Very High evening fatigue class had significantly higher levels of global, cancer-specific, and cumulative life stress. Similarly, in our LPA of depressive symptoms [29], global, cancer-specific, and cumulative life stress varied significantly across the four depressive symptom classes (i.e., None < Subsyndromal < Moderate < High). In addition, decrements in levels of resilience differentiated the classes (i.e., None > Subsyndromal > Moderate > High). Despite the strength of these studies, none of them evaluated for the impact of various types of stress on the severity of both evening fatigue AND depressive symptoms. Therefore, across two cycles of chemotherapy in a large sample of patients with cancer (n = 1334), the study purposes were to identify subgroups of patients with distinct joint evening fatigue AND depressive symptom profiles and evaluate for differences among the subgroups in demographic and clinical characteristics, levels of stress (i.e., global, cancer-specific, cumulative life) and resilience, and the severity of common symptoms.

2. Methods

2.1. Patients and Settings

This study is part of a large, longitudinal study of the symptom experience of oncology outpatients receiving chemotherapy [39–44]. Eligible patients were ≥ 18 years of age; had a diagnosis of breast, gastrointestinal, gynecological, or lung cancer; had received chemotherapy within the preceding four weeks; were scheduled to receive at least two additional cycles of chemotherapy; were able to read, write, and understand English; and gave written informed consent. Patients were recruited from two comprehensive cancer centers, one Veterans Affairs hospital, and four community-based oncology programs during their first or second cycle of chemotherapy.

2.2. Study Procedures

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each of the study sites. Of the 2234 patients approached, 1343 consented to participate. The major reason for refusal was being overwhelmed with their cancer treatment. Patients completed evening fatigue and depressive symptom questionnaires a total of six times over two chemotherapy cycles (i.e., prior to chemotherapy administration, approximately 1 week after chemotherapy administration, and approximately 2 weeks after chemotherapy administration). All of the other measures were completed at enrollment (i.e., prior to the second or third cycle of chemotherapy). A total of 1334 patients completed the evening fatigue and depression measures and were included in this analysis.

2.3. Instruments

2.3.1. Demographic and Clinical Measures

Patients completed demographic and smoking history questionnaires, the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) scale [45], the Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire [46], and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test [47]. The toxicity of each patient’s chemotherapy regimen was rated using the MAX2 score [48]. Medical records were reviewed for disease and treatment information.

2.3.2. Evening Fatigue Measure

The Lee Fatigue Scale (LFS) consists of 18 items designed to assess physical fatigue and energy on a 0 to 10 numeric rating scale [49]. Total fatigue and energy scores are calculated as the mean of the 13 fatigue items and the five energy items, respectively. Higher scores indicate greater fatigue severity and higher levels of energy. Using separate LFS questionnaires, patients were asked to rate each item based on how they felt within 30 min of awakening (i.e., morning fatigue and morning energy) and prior to going to bed (i.e., evening fatigue and evening energy). The LFS has established cutoff scores for clinically meaningful levels of fatigue (i.e., ≥ 3.2 for morning fatigue and ≥ 5.6 for evening fatigue) and energy (i.e., ≤ 6.2 for morning energy and ≤ 3.5 for evening energy) [50]. It was chosen for this study because it is relatively short, easy to administer, and has well-established validity and reliability [49, 51]. In addition, while fatigue and depression are correlated, we accounted for this relationship when selecting our instruments. Specifically, the LFS provides a measure of physical fatigue and not mood or depressive symptomatology. In the current study, the Cronbach’s alphas were 0.96 for morning and 0.93 for evening fatigue and 0.95 for morning and 0.93 for evening energy.

2.3.3. Depressive Symptoms Measure

The 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (CES-D) evaluates the major symptoms in the clinical syndrome of depression [52]. A total score can range from 0 to 60, with scores of ≥ 16 indicating the need for individuals to seek clinical evaluation for depression. The CES-D has well-established validity and reliability [52, 53]. Of note, as a measure of depression, the CES-D has few somatic symptoms. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89.

2.3.4. Stress and Resilience Measures

The 14-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) was used as a measure of global perceived stress according to the degree that life circumstances are appraised as stressful over the course of the previous week [54]. The PSS has well-established validity and reliability [55]. In this study, its Cronbach’s alpha was 0.85.

The 22-item Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) was used to measure cancer-related distress [56]. Patients rated each item based on how distressing each potential difficulty was for them during the past week “with respect to their cancer and its treatment.” Three subscales evaluate perceived levels of intrusion, avoidance, and hyperarousal. Sum scores of ≥ 24 indicated clinically meaningful post-traumatic symptomatology, and scores of ≥ 33 indicated probable post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [57]. The IES-R has well-established validity and reliability [57]. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the IES-R total score was 0.92.

The 30-item Life Stressor Checklist-Revised (LSC-R) is an index of lifetime trauma exposure (e.g., being mugged and sexual assault) [58]. The total LSC-R score is obtained by summing the total number of events endorsed. If patients endorsed an event, they were asked to indicate how much that stressor affected their life in the past year. These responses were averaged to yield a mean “Affected” score. In addition, a PTSD sum score was created based on the number of positively endorsed items (out of 21) that reflect the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition PTSD Criteria A for having experienced a traumatic event. The LSC-R has demonstrated good to moderate test–retest reliability and good criterion-related validity with diverse populations [59].

The 10-item Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CDRS) evaluates a patient’s personal ability to handle adversity [60]. Total scores range from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicative of higher self-perceived resilience. The normative adult mean score in the United States is 31.8 (±5.4) [61]. The CDRS has well-established validity and reliability in oncology patients [62–64]. In this study, its Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90.

2.3.5. Other Symptom Measures

An evaluation of other common symptoms was done using valid and reliable instruments. The symptoms and their respective measures were state and trait anxiety (Spielberger State–Trait Anxiety Inventories [65]), sleep disturbance (General Sleep Disturbance Scale [50]), cognitive function (Attentional Function Index [66]), and pain (Brief Pain Inventory [67]).

2.4. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics and frequency distributions were generated for sample characteristics at enrollment using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 29 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). LPA was used to identify subgroups of patients with distinct joint evening fatigue and depressive symptom profiles over six assessments, using the patients’ scores on the LFS and CES-D. This approach provides a profile description of these two symptoms with two profiles over time. The LPA was performed using Mplus version 8.4 [68].

In order to incorporate expected correlations among the repeated measures of the same variable and cross-correlations of the series of the two variables (i.e., LFS evening fatigue and CES-D scores), we included covariance parameters among measures at the same occasion and those that were one or two occasions apart. Covariances of each variable with the other at the same assessments were included in the model. Autoregressive covariances were estimated with a lag of two with the same measures and with a lag of one for each variable’s series with the other variable. We limited the covariance structure to a lag of two to accommodate the expected reduction in the correlations that would be introduced by two chemotherapy cycles within each set of three measurement occasions and to reduce model complexity [69].

Estimation was carried out with full information maximum likelihood with standard error and a chi-square test that are robust to non-normality and nonindependence of observations (“estimator = MLR”). Model fit was evaluated to identify the solution that best characterized the observed latent class structure with the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), Vuong–Lo–Mendell–Rubin likelihood ratio test (VLRM), entropy, and latent class percentages that were large enough to be reliable [70]. Missing data were accommodated for with the use of the expectation–maximization algorithm [71].

Differences among the joint evening fatigue and depression classes in demographic and clinical characteristics, stress and resilience measures, and symptom severity scores at enrollment were evaluated using parametric and nonparametric tests. Bonferroni corrected p value of < 0.005 was considered statistically significant for the pairwise contrasts (i.e., 0.05/10 possible pairwise contrasts).

3. Results

3.1. LPA

Table 1 displays the fit indices for the one- through six-class solutions. The five-class solution was selected because the BIC for that solution was lower than the BIC for the four-class solution. In addition, the VLMR likelihood ratio test was significant for the five-class solution, indicating that five classes fit the data better than four classes. Although the BIC was smaller for the six-class than for the five-class solution, the VLMR was not significant for the six-class solution, indicating that too many classes were extracted.

| Model | LL | AIC | BIC | Entropy | VLMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Class | −35922.37 | 71,960.73 | 72,262.09 | n/a | n/a |

| 2 Class | −35258.07 | 70,658.15 | 71,027.06 | 0.86 | 1328.58+ |

| 3 Class | −34875.12 | 69,918.24 | 70,354.70 | 0.82 | 765.91+ |

| 4 Class | −34624.41 | 69,442.81 | 69,946.82 | 0.81 | 501.43+ |

| 5 Classa | −34505.12 | 69,230.24 | 69,801.79 | 0.81 | 238.57 ∗ |

| 6 Class | −34414.08 | 69,074.17 | 69,713.27 | 0.82 | ns |

- Note: VLMR = Vuong–Lo–Mendell–Rubin likelihood ratio test for the K vs. K − 1 model.

- Abbreviations: AIC = Akaike Information Criterion, BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion, LL = log-likelihood, n/a = not applicable, and ns = not significant.

- aThe 5-class solution was selected because the BIC for that solution was lower than the BIC for the 4-class solution. In addition, the VLMR was significant for the 5-class solution, indicating that five classes fit the data better than four classes. Although the BIC was smaller for the 6-class than for the 5-class solution, the VLMR was not significant for the 6-class solution, indicating that too many classes were extracted.

- +p < 0.00005.

- ∗p < 0.05.

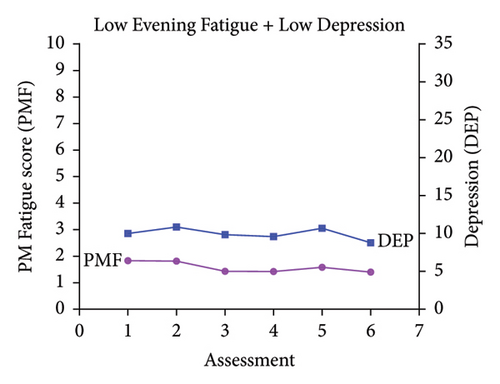

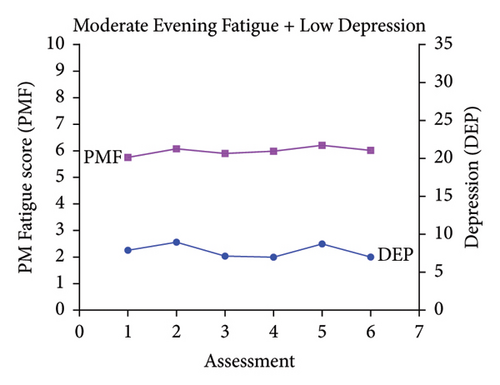

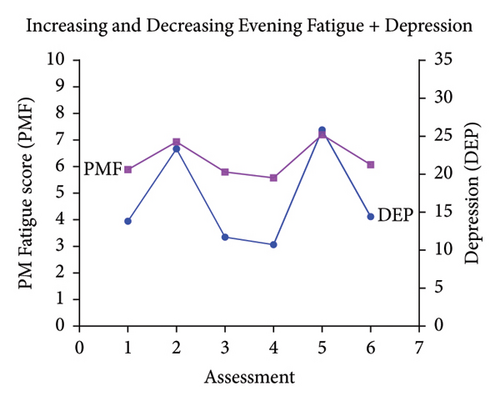

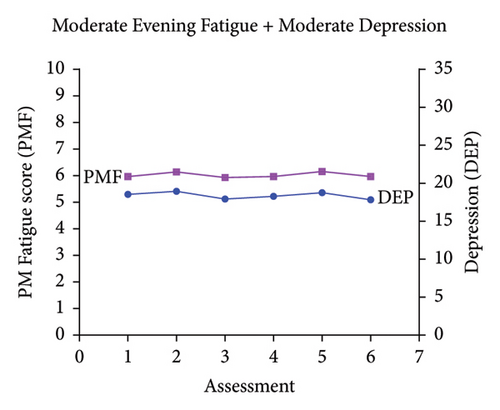

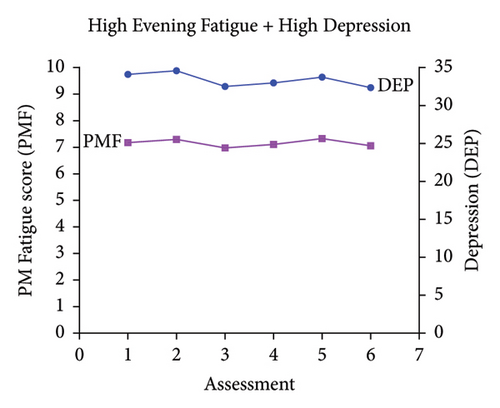

Classes were named based on the clinically meaningful cutoff scores for evening fatigue and depression and the symptom severity score patterns over time. As shown in Figure 1, the scores for the Low Evening Fatigue and Low Depression (Both Low, 20.0%), Moderate Evening Fatigue and Low Depression (Moderate Fatigue and Low Depression, 39.3%), Moderate Evening Fatigue and Moderate Depression (Both Moderate, 27.6%), and High Evening Fatigue and High Depression (Both High, 7.8%) classes remained relatively stable across the two cycles of chemotherapy. For the Increasing and Decreasing Evening Fatigue and Depression class (Both Increasing–Decreasing, 5.3%), severity scores increased sharply at assessments two and five (i.e., assessments following chemotherapy administration) and decreased to enrollment levels at assessments three, four, and six.

3.2. Differences in Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Compared to the Both Low class, the Both High class was younger; more likely to be female; less likely to be married or partnered; more likely to live alone; and more likely to have a lower annual household income (Table 2). In addition, compared to the Both Low class, the Both High class had lower KPS scores; a higher number of comorbid conditions; was more likely to self-report a diagnosis of depression or back pain; more likely to have breast cancer; and less likely to have gastrointestinal cancer. In terms of antiemetic regimen, the Both High class was less likely than the Both Low class to receive a serotonin receptor antagonist and steroid and was more likely to receive a neurokinin-1 receptor antagonist and two other antiemetics.

| Characteristic | Both Low (1) 20.0% (n = 267) |

Moderate Fatigue and Low Depression (2) 39.3% (n = 524) |

Both Increasing–Decreasing (3) 5.3% (n = 71) |

Both Moderate (4) 27.6% (n = 368) |

Both High (5) 7.8% (n = 104) |

Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Age (years) | 60.5 (11.8) | 57.5 (12.3) | 51.6 (12.9) | 56.2 (12.2) | 54.2 (11.8) |

|

| Education (years) | 15.9 (3.1) | 16.5 (2.9) | 17.2 (3.0) | 15.8 (3.0) | 16.0 (3.1) |

|

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.0 (5.1) | 26.1 (5.5) | 25.3 (5.5) | 26.4 (6.1) | 27.3 (6.4) | F = 1.63, p = 0.164 |

| Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test score | 2.8 (2.3) | 3.0 (2.2) | 2.9 (1.9) | 3.1 (3.0) | 3.1 (3.0) | F = 0.41, p = 0.800 |

| Karnofsky Performance Status score | 86.4 (11.2) | 82.1 (11.5) | 77.1 (12.9) | 75.6 (11.8) | 70.4 (11.1) |

|

| Number of comorbid conditions | 2.2 (1.4) | 2.2 (1.3) | 2.1 (1.2) | 2.6 (1.5) | 3.4 (1.7) |

|

| Self-administered Comorbidity questionnaire score | 4.7 (2.8) | 5.0 (2.8) | 4.8 (2.4) | 6.1 (3.3) | 8.1 (4.3) |

|

| Time since diagnosis (years) | 1.8 (3.2) | 2.0 (3.7) | 2.0 (4.0) | 2.2 (4.2) | 1.9 (4.9) | KW, p = 0.788 |

| Time since diagnosis (years, median) | 0.45 | 0.42 | 0.36 | 0.43 | 0.42 | |

| Number of prior cancer treatments | 1.5 (1.5) | 1.6 (1.5) | 1.5 (1.3) | 1.7 (1.5) | 1.7 (1.5) | F = 1.11, p = 0.350 |

| Number of metastatic sites including lymph node involvementa | 1.3 (1.2) | 1.2 (1.2) | 1.0 (1.3) | 1.3 (1.3) | 1.1 (1.2) | F = 1.27, p = 0.281 |

| Number of metastatic sites excluding lymph node involvement | 0.8 (1.0) | 0.8 (1.0) | 0.6 (1.0) | 0.8 (1.1) | 0.6 (1.0) | F = 1.71, p = 0.146 |

| MAX2 score | 0.16 (0.08) | 0.17 (0.08) | 0.22 (0.08) | 0.18 (0.08) | 0.18 (0.08) |

|

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | ||

| Gender (% female) | 68.5 (183) | 76.9 (402) | 90.1 (64) | 81.5 (300) | 85.6 (89) |

|

| Self-reported ethnicity | X2 = 57.06, p < 0.001 | |||||

| White | 58.0 (153) | 75.6 (391) | 71.4 (50) | 72.8 (265) | 55.9 (57) | 1 and 5 < 2 and 4 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 17.4 (46) | 12.0 (62) | 14.3 (10) | 9.1 (33) | 13.7 (14) | 1 > 4 |

| Black | 12.5 (33) | 6.0 (31) | 4.3 (3) | 5.2 (19) | 8.8 (9) | 1 > 2 and 4 |

| Hispanic, mixed, or others | 12.1 (32) | 6.4 (33) | 10.0 (7) | 12.9 (47) | 21.6 (22) | 2 < 4 and 5 |

| Married or partnered (% yes) | 70.8 (187) | 68.6 (354) | 70.4 (50) | 58.4 (211) | 44.7 (46) |

|

| Lives alone (% yes) | 15.2 (40) | 20.1 (104) | 12.7 (9) | 26.9 (97) | 33.0 (34) |

|

| Currently employed (% yes) | 38.2 (100) | 42.5 (220) | 32.9 (23) | 26.0 (95) | 25.0 (26) |

|

| Annual household income | ||||||

| Less than $30,000b | 15.9 (36) | 10.3 (49) | 15.2 (10) | 25.9 (86) | 40.6 (39) | KW, p < 0.001 |

| $30,000 to $70,000 | 24.8 (56) | 18.4 (87) | 13.6 (9) | 24.7 (82) | 18.8 (18) | 2 < 1, 4, and 5 |

| $70,000 to $100,000 | 19.0 (43) | 19.6 (93) | 21.2 (14) | 12.3 (41) | 11.5 (11) | 1 and 3 < 5 |

| Greater than $100,000 | 40.3 (91) | 51.7 (245) | 50.0 (33) | 37.0 (123) | 29.2 (28) | |

| Child care responsibilities (% yes) | 16.3 (43) | 22.2 (113) | 25.7 (18) | 24.2 (87) | 27.5 (28) | X2 = 8.34, p = 0.080 |

| Elder care responsibilities (% yes) | 7.3 (18) | 7.2 (34) | 4.5 (3) | 11.2 (37) | 4.2 (4) | X2 = 8.23, p = 0.084 |

| Past or current history of smoking (% yes) | 29.4 (77) | 36.1 (187) | 28.6 (20) | 37.2 (133) | 44.2 (46) |

|

| Exercise on a regular basis (% yes) | 74.1 (195) | 73.8 (380) | 72.5 (50) | 65.6 (235) | 63.6 (63) |

|

| Specific comorbid conditions (% yes) | ||||||

| Heart disease | 7.5 (20) | 5.2 (27) | 1.4 (1) | 6.5 (24) | 3.8 (4) | X2 = 5.45, p = 0.244 |

| High blood pressure | 34.5 (92) | 29.6 (155) | 16.9 (12) | 28.5 (105) | 36.5 (38) |

|

| Lung disease | 10.9 (29) | 9.5 (50) | 5.6 (4) | 13.3 (49) | 18.3 (19) |

|

| Diabetes | 8.6 (23) | 9.4 (49) | 4.2 (3) | 8.2 (30) | 13.5 (14) | X2 = 4.98, p = 0.289 |

| Ulcer or stomach disease | 4.5 (12) | 3.8 (20) | 1.4 (1) | 5.7 (21) | 10.6 (11) |

|

| Kidney disease | 1.1 (3) | 1.0 (5) | 1.4 (1) | 1.6 (6) | 3.8 (4) | X2 = 5.45, p = 0.244 |

| Liver disease | 7.1 (19) | 6.7 (35) | 2.8 (2) | 6.8 (25) | 4.8 (5) | X2 = 2.33, p = 0.675 |

| Anemia or blood disease | 9.0 (24) | 11.3 (59) | 16.9 (12) | 13.6 (50) | 18.3 (19) | X2 = 8.64, p = 0.071 |

| Depression | 5.6 (5) | 9.4 (49) | 16.9 (12) | 31.3 (115) | 63.5 (66) |

|

| Osteoarthritis | 10.9 (29) | 11.3 (59) | 12.7 (9) | 13.6 (50) | 13.5 (14) | X2 = 1.70, p = 0.790 |

| Back pain | 22.1 (59) | 20.8 (109) | 23.9 (17) | 30.4 (112) | 45.2 (47) |

|

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 3.4 (9) | 2.7 (14) | 4.2 (3) | 2.7 (10) | 5.8 (6) | X2 = 3.27, p = 0.514 |

| Cancer diagnosis | X2 = 46.85, p < 0.001 | |||||

| Breast cancer | 31.5 (84) | 41.6 (218) | 56.3 (40) | 38.3 (141) | 52.9 (55) | 1 < 3 and 5 |

| Gastrointestinal cancer | 42.7 (114) | 29.2 (153) | 12.7 (9) | 30.2 (111) | 19.2 (20) |

|

| Gynecological cancer | 13.1 (35) | 17.6 (92) | 23.9 (17) | 19.6 (72) | 15.4 (16) | NS |

| Lung cancer | 12.7 (34) | 11.6 (61) | 7.0 (5) | 12.0 (44) | 12.5 (13) | NS |

| Prior cancer treatment | ||||||

| No prior treatment | 32.0 (82) | 23.9 (122) | 20.3 (14) | 23.2 (84) | 22.5 (23) | X2 = 18.28, p = 0.107 |

| Only surgery, CTX, or RT | 34.8 (89) | 43.1 (220) | 50.7 (35) | 43.9 (159) | 41.2 (42) | |

| Surgery and CTX, or surgery and RT, or CTX and RT | 23.0 (59) | 20.0 (102) | 17.4 (12) | 18.5 (67) | 17.6 (18) | |

| Surgery and CTX and RT | 10.2 (26) | 12.9 (66) | 11.6 (8) | 14.4 (52) | 18.6 (19) | |

| Metastatic sites | ||||||

| No metastasis | 26.1 (69) | 32.3 (167) | 46.5 (33) | 32.8 (119) | 38.2 (39) | X2 = 20.72, p = 0.055 |

| Only lymph node metastasis | 22.7 (60) | 21.5 (111) | 23.9 (17) | 20.7 (75) | 25.5 (26) | |

| Only metastatic disease in other sites | 25.8 (68) | 21.3 (110) | 8.5 (6) | 21.8 (79) | 14.7 (15) | |

| Metastatic disease in lymph nodes and other sites | 25.4 (67) | 25.0 (129) | 21.1 (15) | 24.8 (90) | 21.6 (22) | |

| Receipt of targeted therapy | ||||||

| No | 64.6 (168) | 69.8 (359) | 74.6 (53) | 71.7 (258) | 75.5 (77) | X2 = 6.27, p = 0.180 |

| Yes | 35.4 (92) | 30.2 (155) | 25.4 (18) | 28.3 (102) | 24.5 (25) | |

| CTX regimen | ||||||

| Only CTX | 64.6 (168) | 69.8 (359) | 74.6 (53) | 71.7 (258) | 75.5 (77) | X2 = 8.49, p = 0.387 |

| Only targeted therapy | 3.1 (8) | 3.3 (17) | 0.0 (0) | 3.1 (11) | 2.9 (3) | |

| Both CTX and targeted therapy | 32.3 (84) | 26.8 (138) | 25.4 (18) | 25.3 (91) | 21.6 (22) | |

| Cycle length | ||||||

| 14 days cycle | 47.2 (126) | 42.2 (220) | 25.4 (17) | 42.7 (156) | 35.3 (36) | KW = 7.85, p = 0.097 |

| 21 days cycle | 46.4 (124) | 48.9 (255) | 73.1 (49) | 50.1 (183) | 58.8 (60) | |

| 28 days cycle | 6.4 (17) | 8.8 (46) | 1.5 (1) | 7.1 (26) | 5.9 (6) | |

| Emetogenicity of the CTX regimen | ||||||

| Minimal/low | 19.5 (52) | 19.0 (99) | 10.4 (7) | 21.6 (79) | 20.6 (21) | KW = 5.39, p = 0.249 |

| Moderate | 64.0 (171) | 62.2 (324) | 62.7 (42) | 57.9 (212) | 57.8 (59) | |

| High | 16.5 (44) | 18.8 (98) | 26.9 (18) | 20.5 (75) | 21.6 (22) | |

| Antiemetic regimen | X2 = 25.78, p = 0.012 | |||||

| None | 7.7 (20) | 7.4 (38) | 1.5 (1) | 8.1 (29) | 4.0 (4) | NS |

| Steroid alone or serotonin receptor antagonist alone | 20.7 (54) | 20.4 (104) | 27.7 (18) | 17.7 (63) | 26.3 (26) | NS |

| Serotonin receptor antagonist and steroid | 51.7 (135) | 48.7 (249) | 41.5 (27) | 48.9 (174) | 32.3 (32) | 1, 2 and 4 > 5 |

| NK-1 receptor antagonist and two other antiemetics | 19.9 (52) | 23.5 (120) | 29.2 (19) | 25.3 (90) | 37.4 (37) | 1 < 5 |

- Note: CTX = chemotherapy, m2 = meters squared.

- Abbreviations: kg = kilograms, KW = Kruskal–Wallis, NK-1 = neurokinin-1, NS = not significant, pw = pairwise, RT = radiation therapy, SD = standard deviation.

- aTotal number of metastatic sites evaluated was 9.

- bReference group.

Compared to the Both Low class, the Both Moderate class was younger; more likely to be female; less likely to be married or partnered; and more likely to live alone. In addition, compared to the Both Low class, the Both Moderate class had lower KPS scores; higher number of comorbid conditions; was more likely to self-report a diagnosis of depression; and less likely to have gastrointestinal cancer.

Compared to the Both Low class, the Both Increasing–Decreasing class was younger; more likely to be female; had more years of education; lower KPS scores; higher MAX2 scores; was less likely to self-report high blood pressure; less likely to have gastrointestinal cancer; more likely to have breast cancer; and more likely to self-report depression.

3.3. Differences in Stress and Resilience Measures

Significant differences in PSS total scores were found among the five latent classes in the expected pattern (i.e., Both Low < Moderate Fatigue and Low Depression < Both Increasing–Decreasing < Both Moderate < Both High; Table 3). Compared to the Both Low class, the Both Moderate and Both High classes reported higher intrusion, avoidance, hyperarousal, and total IES-R scores; higher affected sum, PTSD sum, and total LSC-R scores; and lower CDRS total scores. Compared to the Both Low class, the Both Increasing–Decreasing, Both Moderate, and Both High classes reported higher intrusion, hyperarousal, and total IES-R scores; and higher affected sum, PTSD sum, and total LSC-R scores.

| Measuresa | Both Low (1) 20.0% (n = 267) |

Moderate Fatigue and Low Depression (2) 39.3% (n = 524) |

Both Increasing–Decreasing (3) 5.3% (n = 71) |

Both Moderate (4) 27.6% (n = 368) |

Both High (5) 7.8% (n = 104) |

Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| PSS total score (range 0–56) | 13.4 (6.6) | 15.2 (5.9) | 20.1 (6.8) | 22.9 (6.3) | 31.1 (6.9) |

|

| IES-R total score (≥ 24) | 12.7 (9.7) | 13.9 (8.5) | 18.2 (11.2) | 24.3 (11.9) | 39.3 (16.4) |

|

| IES-R intrusion | 0.6 (0.5) | 0.7 (0.5) | 0.9 (0.6) | 1.2 (0.7) | 2.0 (0.8) |

|

| IES-R avoidance | 0.8 (0.6) | 0.8 (0.6) | 1.0 (0.7) | 1.1 (0.7) | 1.5 (0.8) |

|

| IES-R hyperarousal | 0.3 (0.4) | 0.4 (0.4) | 0.6 (0.5) | 0.9 (0.6) | 1.8 (0.9) |

|

| LSC-R total score (range 0–30) | 5.0 (3.1) | 5.6 (3.6) | 6.6 (4.1) | 6.8 (4.3) | 8.5 (4.7) |

|

| LSC-R affected sum (range 0–150) | 8.1 (6.6) | 9.9 (8.7) | 13.8 (13.3) | 14.4 (12.3) | 22.1 (14.2) |

|

| LSC-R PTSD sum (range 0–21) | 2.1 (2.3) | 2.7 (2.7) | 3.8 (3.4) | 3.6 (3.3) | 5.1 (3.6) |

|

| CDRS total score (range 0–40) | 32.2 (6.3) | 32.0 (5.1) | 30.0 (6.2) | 27.5 (6.3) | 24.3 (6.3) |

|

- Abbreviations: CDRS = Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale, IES-R = Impact of Event Scale-Revised, LSC-R = Life Stressor Checklist-Revised, PSS = Perceived Stress Scale, PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder, SD = standard deviation.

- aClinically meaningful cutoff scores or range of scores.

3.4. Differences in Common Symptoms

Significant differences in depressive symptoms, trait and state anxiety, and morning fatigue were found among the five latent classes in the expected pattern (i.e., Both Low < Moderate Fatigue and Low Depression < Both Increasing-Decreasing < Both Moderate < Both High; Table 4). Compared to the Both Low class, the other four classes reported higher levels of depressive symptoms; higher trait and state anxiety; higher morning and evening fatigue; higher sleep disturbance; higher mean pain interference; lower levels of evening energy; and lower attentional function. Compared to the Both Low class, the Both Increasing–Decreasing, Both Moderate, and Both High classes reported lower levels of morning energy. Compared to the Both Low class, the Both Moderate and Both High classes reported higher worst pain intensity scores. In addition, compared to the Both Low and Moderate Fatigue and Low Depression classes, the Both Moderate and Both High classes were more likely to report both noncancer and cancer pain.

| Symptomsa | Both Low (1) 20.0% (n = 267) |

Moderate Fatigue and Low Depression (2) 39.3% (n = 524) |

Both Increasing–Decreasing (3) 5.3% (n = 71) |

Both Moderate (4) 27.6% (n = 368) |

Both High (5) 7.8% (n = 104) |

Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Depressive symptoms (≥ 16) | 6.4 (4.9) | 7.7 (4.6) | 13.7 (6.9) | 18.8 (5.9) | 34.6 (7.4) |

|

| Trait anxiety (≥ 31.8) | 28.5 (6.9) | 30.2 (6.1) | 35.5 (8.7) | 41.5 (7.9) | 54.7 (8.0) |

|

| State anxiety (≥ 32.2) | 26.6 (7.8) | 28.6 (8.0) | 34.2 (9.9) | 40.2 (9.8) | 56.9 (12.0) |

|

| Morning fatigue (≥ 3.2) | 1.4 (1.5) | 2.6 (1.8) | 3.3 (2.2) | 4.2 (2.1) | 6.0 (2.0) |

|

| Evening fatigue (≥ 5.6) | 2.7 (1.6) | 5.8 (1.6) | 5.8 (2.0) | 6.0 (1.8) | 7.2 (1.7) |

|

| Morning energy (≤ 6.2) | 4.9 (2.7) | 4.8 (2.1) | 3.8 (2.2) | 4.0 (1.9) | 3.2 (2.1) |

|

| Evening energy (≤ 3.5) | 4.2 (2.2) | 3.6 (1.9) | 3.1 (1.8) | 3.4 (1.9) | 2.7 (2.3) |

|

| Sleep disturbance (≥ 43.0) | 37.5 (15.6) | 49.0 (18.0) | 53.2 (18.6) | 61.1 (17.1) | 76.9 (15.2) |

|

| Attentional function (< 5.0 = Low, 5 to 7.5 = Moderate, > 7.5 = High) | 7.7 (1.5) | 6.9 (1.4) | 6.4 (1.7) | 5.4 (1.5) | 4.2 (1.6) |

|

| Worst pain intensity score | 5.2 (2.6) | 5.9 (2.4) | 6.2 (2.7) | 6.4 (2.5) | 7.1 (2.4) |

|

| Mean pain interference score | 1.7 (1.7) | 2.4 (2.1) | 3.2 (2.7) | 4.0 (2.5) | 5.2 (2.7) |

|

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | ||

| Types of pain | X2 = 109.56, p < 0.001 | |||||

| None | 39.2 (103) | 32.0 (164) | 26.1 (18) | 18.8 (68) | 5.8 (6) |

|

| Only noncancer pain | 20.2 (53) | 17.2 (88) | 8.7 (6) | 14.1 (51) | 9.7 (10) | NS |

| Only cancer pain | 20.9 (55) | 25.9 (133) | 39.1 (27) | 28.0 (101) | 27.2 (28) |

|

| Both noncancer and cancer pain | 19.8 (52) | 25.0 (128) | 26.1 (18) | 39.1 (141) | 57.3 (59) | 1, 2, 3, and 4 < 5 |

- Abbreviations: NS = not significant and SD = standard deviation.

- aClinically meaningful cutoff scores.

4. Discussion

This study is the first to identify distinct joint profiles of evening fatigue AND depressive symptoms across two cycles of chemotherapy and evaluate for differences in demographic and clinical characteristics, levels of stress and resilience, and the severity of common symptoms. Of note, 35.4% of the sample exceeded the clinically meaningful thresholds for evening fatigue [50] AND depressive symptoms [52] which underscores the importance of assessing these symptoms concurrently.

While four distinct symptom profiles were identified in our previous LPAs of evening fatigue [3] and depressive symptoms [29], when combined in a joint analysis, five distinct profiles were identified (Figure 1). Consistent with these studies [3, 29] and our LPAs of evening fatigue in patients with gastrointestinal [2] and gynecological [26] cancers, four of the five evening fatigue and depressive symptom profiles that were identified in this study remained relatively stable across two cycles of chemotherapy (i.e., Both Low, Moderate Fatigue and Low Depression, Both Moderate, Both High). However, in studies that used latent growth mixture modeling to identify fatigue or depressive symptom trajectories over single cycles of chemotherapy, the results varied [24, 25, 27, 28]. For example, in two studies that evaluated for average fatigue or depressive symptom trajectories over a single cycle of chemotherapy in the same sample of women with breast cancer [24, 27], depressive symptom trajectories remained relatively stable [27] while the fatigue trajectories for two classes increased over the first week following chemotherapy and then decreased over the second week [24]. In another study of women with breast cancer [25], fatigue trajectories increased in the first few days following chemotherapy and then decreased over the next week. These inconsistencies may be due to differences in symptom measures (e.g., evening fatigue vs. average fatigue severity), analytic method (i.e., latent growth mixture modeling and LPA), timing of the assessments, and cancer types.

It is interesting to note that while evening fatigue and depressive symptom severity scores had similar levels of severity (e.g., low evening fatigue AND low depression for the Both Low class) for four of the five profiles, the severity levels were not concordant for the Moderate Fatigue and Low Depression class. This finding suggests that while evening fatigue and depression are related, these two symptoms are distinct.

While not identified in our studies of evening fatigue [3] or depressive symptom [29] profiles, when these two symptoms were modeled together, a Both Increasing–Decreasing class was identified. This class’s symptom severity scores peaked in the week following the receipt of chemotherapy (i.e., assessments two and four). Most notable was the change in depressive scores from subsyndromal to high levels. Similar trajectories were identified in three studies in women with breast cancer that evaluated daily fatigue [24, 25] or depressive symptoms [27] over a cycle of chemotherapy and in our previous LPA of nausea [72] that identified an Increasing–Decreasing nausea class across the two cycles of chemotherapy. Common findings across these studies were that patients in the Both Increasing–Decreasing class were more likely to be female [72] and have a more toxic chemotherapy regimen (i.e., MAX2 index [72], receipt of doxorubicin [24]). For example, in this study, compared to the other four classes, MAX2 index scores were significantly higher for the Both Increasing–Decreasing class. It is possible that these patterns occur as a result of an acute immune response following the administration of chemotherapy. Specifically, systemic chemotherapy triggers the production of proinflammatory cytokines in the periphery. Then, through signaling to afferent pathways, additional proinflammatory cytokines are produced in the brain which result in the expression of sickness behavior symptoms, including fatigue and depression [73]. Additional research is needed to confirm these findings.

4.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Consistent with our previous LPAs on evening fatigue [2, 3, 26] and depression [29], compared to the Both Low class, the other four classes were more likely to be younger and female (Table 5). This finding is consistent with another study of women with breast cancer that found younger age was a predictor of severe fatigue 2 years after diagnosis [74]. However, in two systematic reviews [14, 23], while female gender was identified as a risk factor for fatigue and depression, associations between these symptoms and age were inconclusive. This inconsistent finding may be due to heterogeneity in the instruments that were used to assess fatigue and depression. Specifically, the authors of one of the reviews stated that due to the heterogeneity in the fatigue measures, they were unable to evaluate overall relationships between specific dimensions of fatigue and patient characteristics [14].

| Characteristica | Moderate Fatigue and Low Depression | Both Increasing–Decreasing | Both Moderate | Both High |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Younger age | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ |

| More years of education | ■ | |||

| More likely to be female | ■ | ■ | ■ | |

| Less likely to be married or partnered | ■ | ■ | ||

| More likely to live alone | ■ | ■ | ||

| Less likely to be employed | ■ | |||

| More likely to have a lower annual income | ■ | |||

| More likely to be White | ■ | ■ | ||

| Less likely to be Asian or Pacific Islander | ■ | |||

| Less likely to be Black | ■ | ■ | ||

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Lower Karnofsky Performance Status scores | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ |

| Higher number of comorbid conditions | ■ | ■ | ||

| Higher comorbidity burden (SCQ score) | ■ | ■ | ||

| Higher MAX2 scores | ■ | |||

| Less likely to self-report high blood pressure | ■ | |||

| More likely to self-report depression | ■ | ■ | ■ | |

| More likely to self-report back pain | ■ | |||

| More likely to have breast cancer | ■ | ■ | ||

| Less likely to have gastrointestinal cancer | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ |

| Less likely to receive a serotonin receptor antagonist and steroid | ■ | |||

| More likely to receive a NK-1 receptor antagonist and two other antiemetics | ■ | |||

| Stress and resilience measures | ||||

| Higher Perceived Stress Scale score | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ |

| Higher Impact of Event Scale-Revised total score | ■ | ■ | ■ | |

| Higher Impact of Event Scale-Revised intrusion score | ■ | ■ | ■ | |

| Higher Impact of Event Scale-Revised avoidance score | ■ | ■ | ||

| Higher Impact of Event Scale-Revised hyperarousal score | ■ | ■ | ■ | |

| Higher Life Stressor Checklist-Revised total score | ■ | ■ | ■ | |

| Higher Life Stressor Checklist-Revised affected sum score | ■ | ■ | ■ | |

| Higher Life Stressor Checklist-Revised PTSD sum score | ■ | ■ | ■ | |

| Lower Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale total score | ■ | ■ | ||

| Symptom characteristics | ||||

| Higher depressive symptoms | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ |

| Higher trait anxiety | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ |

| Higher state anxiety | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ |

| Higher morning fatigue | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ |

| Higher evening fatigue | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ |

| Lower morning energy | ■ | ■ | ■ | |

| Lower evening energy | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ |

| Higher sleep disturbance | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ |

| Lower attentional function | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ |

| Higher worst pain intensity score | ■ | ■ | ||

| Higher mean pain interference score | ■ | ■ | ■ | ■ |

- Abbreviations: NK-1 = neurokinin-1, PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder, and SCQ = Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire.

- aComparisons are done with the Low Evening Fatigue and Low Depression Class.

Compared to the Both Low class, the Both Moderate and Both High classes were less likely to be married or partnered, more likely to live alone, and either less likely to be employed or have a lower annual household income. These findings are consistent with our prior report of depressive symptom profiles [29], and three studies of oncology patients receiving chemotherapy that reported that being unmarried [8, 75], living alone [76], or being employed less than full-time [75] were associated with more severe depressive symptoms. In contrast, these relationships were not identified across our analyses of evening fatigue [2, 3, 26]. Being unmarried or living alone may decrease one’s household income and may be a proxy for social support which has a known relationship with depression [23, 77]. Given the negative effects of social isolation on mental and physical health [77], assessment of patients’ social support network is important in order to provide referrals to appropriate social services.

In terms of clinical characteristics, compared to the Both Low class, the other four classes had significantly lower KPS scores. These findings are consistent with our previous reports on evening fatigue [2, 3, 26] and depressive symptom [29] profiles and in other studies of fatigue [20] and depressive symptoms [75] in oncology patients receiving chemotherapy. Of note, KPS scores for the Both Increasing–Decreasing, Both Moderate, and Both High classes were in the 70 s, which is indicative of inability to maintain normal activity or to work [45]. While exercise is one of the primary interventions that is recommended to reduce both fatigue [78] and depressive symptoms [79], patients with moderate and severe evening fatigue and depressive symptoms may be unable to implement an exercise program on their own. It is likely that these patients will need referrals to physical and occupational therapy to maintain and/or improve physical function to ensure success. It is interesting to note that in this study, exercising on a regular basis was not a protective risk factor for more severe evening fatigue and depressive symptoms. This finding may be due to the fact that characteristics of the exercise program that may influence its effectiveness in reducing fatigue [78] and depressive [79] symptoms (e.g., type, dose, intensity, and quality) were not captured in this study.

Compared to the other three classes, the Both Moderate and Both High classes had a significantly higher number of comorbid conditions and a higher comorbidity burden. Similar findings were reported in our previous analyses of evening fatigue [2, 3, 26] and depressive symptom [29] profiles. In addition, in our recent study that evaluated the symptom experience of patients with low and high multimorbidity [80], patients with high multimorbidity reported higher levels of fatigue and depressive symptoms and were more likely to self-report a diagnosis of depression. It is interesting to note that only two comorbid conditions differentiated the Both Low and Both High classes (i.e., self-reported history of depression and back pain). This finding may suggest that the presence of multiple, comorbid conditions may contribute more to the severity of evening fatigue AND depressive symptoms than individual comorbid conditions alone.

In terms of specific cancer diagnoses, the Both Increasing–Decreasing and Both High classes were more likely to have a diagnosis of breast cancer while the Both Low class was more likely to have a type of gastrointestinal cancer. While these findings are consistent with our report on evening fatigue profiles [3], in our other analysis of depressive symptom profiles [29], cancer type did not differentiate the subgroups. These findings may be related to gender. For example, in our prior LPA of evening fatigue among patients with gastrointestinal cancer [2], female gender was a risk factor for more severe levels of evening fatigue. Additional evaluations of evening fatigue and depressive symptom profiles in samples of patients with other cancer types that are not gender specific may help clarify this relationship.

In terms of treatment-specific risk factors, only the type of antiemetic regimen differentiated the Both Low and Both High classes. While the reason for this finding is not entirely clear, it may be related to treatment for specific cancer types (i.e., breast vs. gastrointestinal). Alternatively, given that the presence of a higher number of comorbid conditions is associated with a higher symptom burden [80], clinicians may prescribe stronger antiemetic regimens to patients in the Both High class because of their higher comorbidity burden.

4.2. Stress and Resilience

Global perceived stress scores increased in a stepwise fashion across the joint evening fatigue and depressive symptom profiles (i.e., Both Low < Moderate Fatigue and Low Depression < Both Increasing–Decreasing < Both Moderate < Both High). In terms of cancer-related distress at enrollment, IES-R scores for the Both Moderate class indicate post-traumatic stress symptomatology, while scores for the Both High class indicate probable PTSD. Similar patterns and clinically meaningful levels of general and cancer-specific stress were found in our previous LPA of depressive symptoms [29]. It is interesting to note that in our prior evaluation of evening fatigue profiles and stress [34], the mean PSS levels for the High and Very High evening fatigue classes were lower than those for the Both Moderate and Both High classes in this analysis. Similarly, IES-R scores for the High and Very High evening fatigue classes were below the threshold for probable PTSD [34]. Taken together, these findings suggest that general and cancer-specific stress may have larger impacts on depressive symptoms than physical symptoms such as evening fatigue.

Consistent with our previous analyses of evening fatigue [34] and depressive symptom profiles [29], the Both High class reported a significantly higher number of stressful life events at enrollment as compared to patients in the other four classes. These findings are consistent with prior research in patients with breast cancer that reported cumulative lifetime stress is associated with higher levels of fatigue and/or depressive symptoms [81, 82].

Consistent with our previous analysis on depressive symptom profiles [29], the Both Moderate and Both High classes had significantly lower levels of resilience at enrollment as compared to the other three classes. In addition, CDRS total scores for the Both Moderate and Both High classes indicated clinically meaningful decrements in resilience [83]. These findings are consistent with other studies of oncology patients receiving cancer treatment that reported lower levels of resilience were associated with higher levels of fatigue [84, 85] and depressive symptoms [37, 82]. Furthermore, the resilience scores for the Both Increasing–Decreasing, Both Moderate, and Both High classes were below the U.S. population norms [61]. Taken together, these findings support the hypothesis that greater resilience may protect against decrements in physical and mental health among patients receiving cancer treatment.

Interventions aimed at building resilience and reducing stress in patients with cancer may help to mitigate these negative symptom trajectories [32]. For example, cognitive behavioral therapy-based interventions provide patients with the skills to adjust to stressful experiences through cognitive restructuring, behavioral activation, and relaxation [31]. Given the growing body of the literature that supports the efficacy of these interventions, recent guidelines from the American Society for Clinical Oncology and the Society for Integrative Oncology recommend cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction interventions for treatment of cancer-related fatigue [78] and depression [79] during cancer treatment.

4.3. Common Co-Occurring Symptoms

The severity of depressive symptoms, trait and state anxiety, and morning fatigue increased in a stepwise fashion across the evening fatigue and depressive symptom profiles (i.e., Both Low < Moderate Fatigue and Low Depression < Both Increasing–Decreasing < Both Moderate < Both High). Prior research using factor analysis supports the co-occurrence of these symptoms as a symptom cluster [86] and supports the hypothesis that evening fatigue and depressive symptoms share common underlying mechanism(s). Ongoing investigation into the ways in which various types of stress impact the severity of these symptoms as well as their response to stress reduction and resilience-building interventions are needed.

From a clinical perspective, the Increasing–Decreasing, Both Moderate, and Both High classes had subsyndromal to clinically meaningful levels of depressive symptoms, moderate-to-severe pain [87], and clinically meaningful levels of trait and state anxiety, morning and evening fatigue, morning and evening energy, sleep disturbance, and moderate-to-low attentional function. These findings suggest that, for over 40% of the sample, symptoms common to oncology patients are inadequately treated. Assessment of fatigue and depressive symptom severity during clinical visits will help identify patients at greatest risk for this higher symptom burden.

4.4. Limitations

Several limitations warrant consideration. The primary reason patients refused to participate in this study were feeling overwhelmed with their cancer treatment. Therefore, findings from this study may underestimate evening fatigue and depressive symptoms in patients receiving chemotherapy. Given that oncology patients may experience post-traumatic growth during the course of their cancer treatment [32], evaluations of stress and resilience measures over time in relationship to evening fatigue and depressive symptoms are needed. In addition, information on concurrent treatment for depression during the study period was not available. Finally, given that the sample was primarily white, female, well-educated, and reported a moderate-to-high household income, these findings may not generalize to all patients with cancer.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, through the identification of subgroups of patients with distinct joint evening fatigue AND depressive symptom profiles, several risk factors for more severe evening fatigue AND depressive symptom experiences were elucidated. Clinicians may use these risk factors to identify patients at greatest risk for poorer outcomes. Notably, patients with more severe evening fatigue AND depressive symptom profiles had low functional status and high comorbidity burden. Clinicians need to take these factors into account when prescribing interventions to treat these symptoms. For example, referrals to physical or occupational therapy may improve patient outcomes when exercise is prescribed. Given that patients with more severe evening fatigue and depressive symptoms reported higher levels of general, cancer-specific, and cumulative life stress and lower resilience, it supports the hypothesis that dysregulation of stress pathways may contribute to the severity of these symptoms. In addition to exercise, cognitive behavioral therapy or mindfulness-based stress reduction may help patients build resilience, improve their stress levels, and reduce the severity of evening fatigue and depressive symptoms.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (CA134900). Dr. Christine A. Miaskowski is an American Cancer Society Clinical Research Professor. Dr. Carolyn S. Harris has been supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (CA286967). Dr. Joosun Shin has been supported by the Mittelman Family Fund Fellowship for Integrative Therapy. This material is the result of the work supported with resources at the VA Portland Health Care System. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, or the United States Government.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data for this study are available upon reasonable request from Dr. Christine A. Miaskowski following the completion of a data transfer agreement with the University of California, San Francisco.