Healthcare Professionals’ Perspectives on ePROMs in Surgical Breast Cancer Follow-Up: A Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

Background: The growing number of breast cancer survivors underscores the need for tailored follow-up care, particularly focussing on person-centred outcomes in surgical follow-ups. Electronic patient-reported outcome measures (ePROMs) have the potential to enhance person-centred care (PCC) by systematically integrating patient perspectives into clinical practice. However, the barriers and facilitators for the utilization of ePROMs in surgical breast cancer follow-ups remain unclear.

Methods: This study utilized a sequential explanatory mixed-methods design. Quantitative data were collected via a survey among healthcare professionals (HCPs) to assess their familiarity with and perspectives on ePROMs. These findings informed focussed ethnographic qualitative research, including participant observations and interviews, to explore the practical application of ePROMs in clinical practice. Data integration involved a joint display analysis to develop comprehensive insights.

Results: While most HCPs (88%) expressed interest in learning more about ePROMs, only 20% agreed that ePROMs improved treatment and care. Time constraints (reported by 56%) and limited system integration (68% were unfamiliar with access via EMR) were reported as key barriers. Nurses prioritized experiential and patient-specific approaches, often relying on intuition rather than systematic use of ePROMs, whereas surgeons viewed ePROMs as tools for improving resource allocation and surgical outcomes. Knowledge gaps and a lack of organizational support were prevalent, hindering the consistent application of ePROMs in routine care.

Conclusions: ePROMs have untapped potential to transform surgical follow-ups in breast cancer care by aligning clinical practices with person-centred outcomes. Effective integration requires addressing technical and organizational barriers, enhancing HCPs’ competencies and fostering a supportive culture for systematic ePROM utilization. Tailored implementation strategies are a key to fully realizing the benefits of ePROMs in achieving PCC.

1. Introduction

Breast cancer is the most prevalent cancer among women globally, with approximately 2.3 million new cases diagnosed in 2022 [1]. The survival rate of breast cancer is 75% in most developed countries [2] and 90% in Denmark [3]. Breast cancer survivors face significant physical and psychological challenges from their cancer treatment, including sleep disturbance, fatigue, depressive mood, cognitive dysfunction and body image issues [4–10].

The increasing number of women surviving breast cancer highlights the need for considering the organization of follow-up. Breast cancer follow-up refers to the ongoing care and monitoring that breast cancer survivors receive after completing their curative treatment [11]. In the literature, this mainly targets supportive care, symptom management and sequelae after chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy [7, 12–14]. There is evidence that breast cancer survivors who undergo mastectomy have worse body image, sexual health and higher levels of anxiety compared with women undergoing breast-conserving therapy and that different forms of breast surgery and reconstruction positively affect patients’ quality of life [15, 16]. Surgical follow-up, including potential reconstructive or corrective procedures, may influence patients’ sense of recovery and well-being after breast cancer surgery, providing support to facilitate a return to normal life postcancer [11]. However, for a comprehensive follow-up related specifically to the surgical treatment of breast cancer, it is recommended to also address patients’ experiences of aesthetic and functional outcomes, as well as their experiences of body image, to provide person-centred evaluation after surgical therapy [17–21]. A person-centred approach focusses on the care and treatment of the needs of individuals, emphasizing that individual preferences, needs and values guide clinical decisions and that clinicians provide care that is respectful and responsive to patients [22]. According to Andersson et al. [23], person-centred care (PCC) is best understood as a relational, ethical and contextual approach that recognizes the uniqueness, dignity and agency of the person and aims to support meaningful living rather than merely treating disease. This conceptualization underscores the importance of engaging with patients not only as recipients of care but as active partners whose life context and personal meaning should shape the care process [23]. Therefore, surgical follow-up care should strike a balance between patient needs and preferences and the costs to the healthcare system [24].

Research demonstrates that one way to accommodate PCC is by continuous evaluation of electronic patient-reported outcome measures (ePROMs) to assess symptoms, leading to improved and person-centred communication between patients with breast cancer and healthcare professionals (HCPs) [23, 25, 26]. Furthermore, by systematically collecting patient-reported data, clinicians gain insights into the patient’s perspective, which can inform discussions and shared decision-making [23]. The use of ePROMs in breast cancer follow-up may add benefits, yet implementation barriers are expected to be comparable to those seen in other cancer types and surgical fields. In oncology, described barriers include limited clinician time, lack of integration with electronic records and uncertainty about the clinical relevance of ePROM data [27, 28]. In orthopaedics, common challenges are low patient digital literacy, which may contribute to reduced patient response rates, along with insufficient staff training and logistical issues with integrating ePROMs into workflows [29, 30]. These similarities suggest that successful implementation in breast cancer surgery may benefit from strategies that address both technical and cultural barriers [31]. Response rates between 60% and 80% when using ePROMs in breast cancer follow-ups are reported [32]. These rates are comparable to findings from previous studies on ePROMs in routine clinical practice [33–35]; however, they indicate room for improvement. Further research is needed to identify barriers and facilitators for using ePROM in follow-ups related to breast cancer surgery [25]. While most existing studies focus on patient experiences, there is limited evidence on how HCPs perceive and engage with ePROMs in surgical follow-up, despite their central role in implementation [26, 31, 36, 37]. This represents a substantial knowledge gap, as successful integration of ePROMs into routine clinical care relies heavily on clinician engagement, usability and perceived clinical value [38].

ePROMs in the field of breast cancer surgery have the potential to involve patients by inviting them to contribute with their preoperative and postoperative expert knowledge on their own experiences, values and concerns. Moreover, ePROMs may support systematic and person-centred follow-ups related to surgical outcomes. This potential has yet to be demonstrated in clinical trials [26, 27], particularly in areas where clinical needs remain unmet. A key field is the absence of standardized, validated tools for assessing body image in breast cancer surgery patients limiting systematic monitoring and intervention [25]. These clinical gaps highlight the need for research addressing both patient-reported outcomes and their integration into clinical practice from a HCP perspective.

- 1.

In-person consultation (T1): A physical meeting with a nurse 4 days postprimary breast cancer surgery.

- 2.

Phone or video consultation (T2): Conducted 11 months postdiagnosis for upfront surgical therapy or 18 months for neoadjuvant and surgical therapy. This optional follow-up focusses on body image and surgical outcomes, allowing referral to a plastic surgeon if necessary.

- 3.

In-person consultation with a plastic surgeon (T2-2): Held two to 3 months after T2, involving both a nurse and a plastic surgeon to evaluate surgical outcomes and discuss further procedures to improve body image.

The multimethod study involves an education programme for nurses and surgeons, the administration of BREAST-Q [39] as proactive ePROMs during follow-up, feedback on ePROM scores to HCPs and the option for patients to request follow-up consultations (Supporting Information 1 and 2).

The BREAST-Q is a validated and frequently used tool for monitoring patient outcomes in plastic and breast surgery. However, there is limited knowledge regarding its active use in follow-up care and the alignment with the vision of a person-centred approach. Given the emphasis on PCC in the organization in which the study takes place, PCC is an underpinning theoretical perspective that aims to be incorporated into clinical practice. The intervention on ePROMs to women diagnosed with breast cancer intends to enhance PCC by systematically monitoring patients’ symptoms and health-related quality of life and tailoring follow-up care to individual patient needs and preferences.

This study aimed to evaluate nurses’ and surgeons’ (hereafter referred to as HCPs) perspectives on the ePROM intervention for follow-up in women diagnosed with breast cancer and their opportunities for person-centred practice, to investigate HCPs’ utilization of ePROMs and to explain these findings to obtain a comprehensive understanding of how the ePROM is used in routine clinical practice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

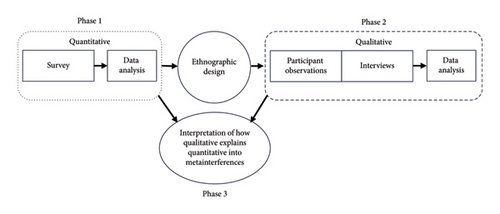

A sequential explanatory mixed-methods design consisting of three phases was performed [40, 41] (Figure 1). Phase one included a cross-sectional survey with HCPs. The survey results built phase two by identifying key areas for exploration, guiding the purposive selection of participants and shaping the development of observation and interview guides. The quantitative study in phase one was followed by a focussed ethnographic study (phase two) including participant observations and semistructured interviews to explain the quantitative results in depth. Finally, the two strands were merged for a third analysis (phase three). Hence, integration occurred at design, methods and interpretation levels [41].

The qualitative and quantitative research components represent various paradigmatic traditions, including diverse ontological, epistemological and methodological assumptions. This study employed a constructivist paradigm for applied practice [42]. The quantitative component developed knowledge about how HCPs report their own practices, opportunities and their knowledge about the ePROM intervention. The qualitative component developed data that explain survey findings by providing in-depth insights into HCPs’ practices, behaviours and experiences.

The study was conducted at the Department of Plastic and Breast Surgery at Zealand University Hospital, Denmark. The hospital is one of five institutions in Denmark performing breast cancer surgical therapy. At the time of the study, the department was undergoing organizational changes and was still affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, which had reduced its clinical capacity and impacted workflow stability. The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki [43], which is registered with the Scientific Ethics Review Committee of the Zealand Region of Denmark (SJ-914, EMN-2021-01530) and the Danish Data Protection Agency (REG-154-2020). The EQUATOR guideline Good Reporting of A Mixed Methods Study (GRAMMS) checklist is used for reporting the study, see Supporting Information 3 [44].

2.2. Sampling Methods

In phase one, population sampling was used by inviting all eligible HCPs (N = 69) within the department to participate voluntarily [45]. The department has a few experienced nurse assistants who, aside from IV medication, perform tasks similar to nurses and were thus included in the survey. Nurse and surgeon leaders were included as they hold clinical roles alongside leadership. The majority of HCPs observed and interviewed were the same, representing all essential roles involved in the ePROM intervention.

Phase two included a nested sample from phase one as HCPs performing consultations in the outpatient clinic were purposefully sampled for interviews, as best suited to provide perspectives on ePROMs based on their follow-up roles. When HCPs consulted with a patient who had completed ePROMs, the researcher requested permission to observe the consultation.

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Survey

The survey was a 39-item study-specific questionnaire developed by the research team. To assess face validity, the initial version of the questionnaire was reviewed by three experienced HCPs (two nurses and one surgeon) from the department. They provided feedback on the relevance, clarity and comprehensiveness of each item to ensure alignment with clinical realities and the aims of the study. Based on their input, revisions were made to improve item phrasing, eliminate ambiguity and enhance content relevance. This process supported the development of a questionnaire that was understandable and contextually appropriate for the target population of HCPs [46]. Items one to seven were demographic related to the HCP background and functions. Subsequently, 11 questions focussed on HCPs’ experiences with PCC, inspired by the person-centred practice inventory [47], and 21 questions focussed on the experiences of using and participating in the ePROM intervention. Responses were a five-point Likert scale (Strongly disagree, Disagree, Neutral, Agree and Strongly agree). In addition, the participants had the opportunity to expand on their responses in a column for open-ended responses during the survey. The survey was distributed via an online platform, SurveyXact, a secure data management application, using a specific hyperlink [48]. The survey was distributed on 1 September 2023, with reminders sent at weekly intervals. The survey closed 4 weeks after its initial distribution.

2.3.2. Observations and Interviews

Focussed ethnography, with participant observations and semistructured in-depth interviews, was applied to enhance the setting-specific, problem-focussed, and short-duration consultations between HCPs and patients [49]. This was conducted by the first author (Stine Thestrup Hansen), a female senior researcher employed at the department with in-depth knowledge of the department and the patient trajectories. As an insider researcher, Stine Thestrup Hansen’s position enabled trust and access but also necessitated continuous reflexivity to address potential observer bias; this was supported by regular analytical discussions with external co-authors to strengthen neutrality and ensure trustworthiness. Participant observations and interviews were based on observational and interview guides developed for this study (see Supporting Information 4). Participant observations were systematically documented through detailed field notes. The participant observations informed the development of the interview guide, provided contextual knowledge about the use of the ePROM intervention and were used to verify and further inform the interviews, ensuring that the interview questions were relevant to the observed practices and potential challenges in the clinical setting [50].

The interviews were prearranged at the participants’ convenience and conducted face-to-face, except for a single interview that was conducted by phone due to the participant’s preference. Participant observations and interviews were conducted from November 2023 to June 2024. However, one interview was conducted in January 2023 with an HCP who was an essential figure in the intervention, following the person’s resignation from the hospital.

2.4. Analysis

2.4.1. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistical analysis was used to produce the means, standard deviations and percentages to provide an overview of the key patterns and characteristics of the sample population [40].

2.4.2. Analysis of Qualitative Data

The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. NVivo software was used to conduct the qualitative data analysis [51]. Stine Thestrup Hansen, Lone Jørgensen and Karin Piil conducted a basic thematic analysis based on Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis to identify, analyse and report the themes and data [52, 53]. The analysis, grounded in quantitative data and integrated with qualitative findings, led to the development of metainferences that synthesize insights from both strands, offering a comprehensive understanding of the findings.

2.4.3. Joint Display Analysis

The merging of quantitative and qualitative data was achieved using a data-linking strategy to identify connections between the two datasets [36]. This process led to the labelling of overarching constructs. The findings from both datasets, related to these constructs, were then organized as a joint display by outlining a side-by-side diagram in a horizontal table. A joint display analysis was conducted by examining both quantitative and qualitative results together. In accordance with Fetters et al. [41], the joint display was used as an active analytical tool to facilitate a systematic comparison and synthesis of the two data strands [41]. This involved iterative interpretation, whereby quantitative results informed targeted exploration in the qualitative data. Patterns of convergence, divergence and expansion were identified and interpreted through author discussions to achieve integration beyond simple juxtaposition. This integrated approach enabled the development of new interpretations, which were listed in a metainterference column.

3. Results

3.1. The Quantitative Results

In total, 69 HCPs (27 surgeons, 42 nurses) were invited to participate in the survey. Of the participants, 39 did not access the questionnaire (56%), 8 (12%) did partly complete the questionnaire, and 22 (32%) completed the questionnaire. Table 1 shows demographic data for the respondents and the nonrespondents with characteristics presented as numbers and means. Data on nonrespondents’ profession, specialist function, education and departmental function were not available, as these variables were not systematically recorded at an individual level for HCPs who did not respond to the survey.

| Characteristics | Respondents N (%) | Nonrespondents N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 5 | (7) | 11 | (16) |

| Female | 25 | (36) | 28 | (41) |

| Age, mean (range) | 49 | (25–66) | 41 | (25–71) |

| Profession | ||||

| Surgeon | 8 | (12) | 19 | (28) |

| Nurse | 20 | (28) | 19 | (28) |

| Nurse assistant | 2 | (3) | 1 | (1) |

| Speciality | ||||

| Plastic surgery | 11 | (36) | ||

| Breast surgery | 5 | (17) | ||

| Both plastic and breast surgery | 14 | (47) | ||

| Specialist function | ||||

| Research/development | 9 | (30) | ||

| Education | 2 | (7) | ||

| Leader/management? | 4 | (13) | ||

| Others∗ | 15 | (50) | ||

| Departmental function | ||||

| Outpatient clinic | 12 | (40) | ||

| Ward | 7 | (23) | ||

| Outpatient clinic and ward | 6 | (20) | ||

| Administrative | 5 | (17) | ||

- ∗Participants identifying as ‘others’ frequently commented that they were basic-level nurses or surgeons without a specific functional role.

Nearly half of the invited female HCPs responded to the survey, while two-thirds of the invited male HCPs did not participate. Among the respondents, nurses were more prominently represented than surgeons. The majority of participants who completed the survey reported working primarily in the outpatient clinic.

The results indicated that work conditions, such as time limitations and a lack of experience with ePROM, constrained the ability of HCPs to deliver PPC, although they generally reported positive intentions towards the implementation of ePROMs.

The majority of respondents expressed a clear interest in incorporating patient satisfaction and quality of life into plastic and breast surgery care, coupled with a strong desire to gain deeper insights into patients’ experiences and outcomes. Specific methods for capturing and utilizing ePROMs remained unclear to HCPs, and structural support for integrating ePROMs and patient preferences into care planning was limited.

While most HCPs perceived their practice as holistic, the connection to PPC, particularly through the use of ePROMs, was not operationalized, highlighting potential gaps in aligning care with the principles of person-centred practice.

Finally, knowledge of the ePROM intervention was inconsistent across the department. HCPs working in outpatient clinics, where the intervention was primarily applied, were more familiar with it. Responses to items 28–32 revealed a general lack of awareness regarding the purpose, function and accessibility of PROMs, highlighting barriers such as time constraints and limited familiarity with ePROMs in clinical practice. Approximately one-third of HCPs reported that their professional potential, a key characteristic of a person-centred practice culture, was not being fully utilized, indicating room for development. This was further supported by responses to a question about interest in learning more about the use of ePROMs, to which the majority expressed a positive interest. For details, see Table 2.

| Questions | Frequency and percentage of response | Mean score (n of respondents) | Standard deviation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree | |||

| 8. I have the opportunity to use my full professional potential in my work | n = 0 | n = 8 | n = 2 | n = 7 | n = 8 | 3.6 (25) | 1.4207 |

| 0% | 32% | 8% | 28% | 32% | |||

| 9. I have the professional competencies to provide individual treatment and/or care | n = 0 | n = 3 | n = 4 | n = 11 | n = 7 | 3.77 (25) | 1.2194 |

| 0% | 12% | 16% | 44% | 28% | |||

| 10. I can perform my clinical work in accordance with my beliefs and values | n = 0 | n = 3 | n = 6 | n = 13 | n = 3 | 3.6 (25) | 0.9712 |

| 0% | 12% | 24% | 52% | 12% | |||

| 11. I seek to gain insight into patient satisfaction related to plastic and breast surgery | n = 0 | n = 0 | n = 3 | n = 7 | n = 15 | 4.4 (25) | 0.7141 |

| 0% | 0% | 12% | 28% | 60% | |||

| 12. I seek to gain insight into patients’ quality of life related to plastic and breast surgery | n = 0 | n = 1 | n = 1 | n = 8 | n = 15 | 4.4 (25) | 0.7702 |

| 0% | 4% | 4% | 32% | 60% | |||

| 13. I ask for feedback on what the treatment and care mean to the patient | n = 0 | n = 2 | n = 4 | n = 9 | n = 10 | 4.0 (25) | 0.9539 |

| 0% | 8% | 16% | 36% | 40% | |||

| 14. I find it relevant to speak with patients about their satisfaction with breast surgery | n = 0 | n = 2 | n = 2 | n = 11 | n = 10 | 4.1 (25) | 0.8981 |

| 0% | 8% | 8% | 44% | 40% | |||

| 15. I find it relevant to speak with patients about their quality of life related to breast surgery | n = 1 | n = 1 | n = 1 | n = 11 | n = 11 | 4.2 (25) | 1.0000 |

| 4% | 4% | 4% | 44% | 44% | |||

| 16. I have terms and conditions to organize care and/or patient pathways while considering each patient’s preferences | n = 2 | n = 4 | n = 12 | n = 5 | n = 2 | 3.0 (25) | 1.0198 |

| 8% | 16% | 48% | 20% | 8% | |||

| 17. I provide holistic care and/or treatment that considers the whole person | n = 0 | n = 2 | n = 4 | n = 11 | n = 8 | 4.0 (25) | 0.9128 |

| 0% | 8% | 16% | 44% | 32% | |||

| 18. I have the terms and conditions to work in a person-centred/holistic manner with treatment and/or care for my patients | n = 1 | n = 7 | n = 9 | n = 8 | n = 0 | 2.9 (25) | 0.8888 |

| 4% | 28% | 36% | 32% | 0% | |||

| 19. Our culture supports research in and development of our clinical practices | n = 1 | n = 1 | n = 10 | n = 8 | n = 5 | 3.6 (25) | 1.0000 |

| 4% | 4% | 40% | 32% | 20% | |||

| 20. I feel well-informed about the intentions regarding the introduction of PROMs in clinical practice | n = 2 | n = 7 | n = 2 | n = 8 | n = 6 | 3.3 (25) | 1.3503 |

| 8% | 28% | 8% | 32% | 24% | |||

| 21. I am familiar with the instruction on how to use patient-reported outcomes measures (PROM) in treatment and care for women diagnosed with breast cancer (also known as BREAST-Q), which describes my responsibilities regarding the PROM programme and the BREAST-Q questionnaire | n = 4 | n = 8 | n = 1 | n = 7 | n = 5 | 3.0 (25) | 1.4571 |

| 16% | 32% | 4% | 28% | 20% | |||

| 22. I know how to access the PROM responses through the electronic medical record system | n = 8 | n = 5 | n = 4 | n = 2 | n = 6 | 2.7 (25) | 1.5947 |

| 32% | 20% | 16% | 8% | 24% | |||

| 23. I have the opportunity to familiarize myself with PROM data | n = 8 | n = 4 | n = 6 | n = 2 | n = 5 | 2.6 (25) | 1.5198 |

| 32% | 16% | 24% | 8% | 20% | |||

| 24. I like the visual layout when accessing PROM data | n = 3 | n = 4 | n = 14 | n = 3 | n = 1 | 2.8 (25) | 0.9574 |

| 12% | 16% | 56% | 12% | 4% | |||

| 25. I gain new insights into patients’ experiences of physical and psychosocial well-being through their responses to PROM | n = 4 | n = 2 | n = 10 | n = 3 | n = 6 | 3.2 (25) | 1.3540 |

| 16% | 8% | 40% | 12% | 24% | |||

| 26. I have enough time to prepare for consultations with PROM data | n = 6 | n = 2 | n = 12 | n = 2 | n = 3 | 2.7 (25) | 1.2675 |

| 24% | 8% | 48% | 8% | 12% | |||

| 27. I wish to integrate the information from the PROM data into my consultations with patients | n = 2 | n = 3 | n = 11 | n = 4 | n = 5 | 3.2 (25) | 1.1733 |

| 8% | 12% | 44% | 16% | 20% | |||

| 28. I use PROM data as a basis for conversations with patients | n = 6 | n = 4 | n = 9 | n = 3 | n = 3 | 2.7 (25) | 1.3076 |

| 24% | 16% | 36% | 12% | 12% | |||

| 29. PROMs improve my treatment and/or care for patients | n = 5 | n = 3 | n = 13 | n = 2 | n = 2 | 2.7 (25) | 1.1372 |

| 20% | 12% | 52% | 8% | 8% | |||

| 30. PROMs strengthen my foundation for making clinical decisions in practice, in collaboration with the patient | n = 5 | n = 3 | n = 11 | n = 2 | n = 3 | 2.7 (24) | 1.2503 |

| 21% | 13% | 46% | 8% | 13% | |||

| 31. I feel confident in my professional abilities to engage patients in discussions about their responses to the BREAST-Q questionnaire | n = 4 | n = 4 | n = 7 | n = 5 | n = 4 | 3.0 (24) | 1.3344 |

| 17% | 17% | 29% | 21% | 17% | |||

| 32. I have opportunities to address issues that are identified through PROMs (e.g. scheduling follow-up appointments within our department, referring to the late effects clinic, or other appropriate management) | n = 5 | n = 3 | n = 8 | n = 5 | n = 3 | 2.9 (24) | 1.3160 |

| 21% | 13% | 33% | 21% | 13% | |||

| 33. I don’t have enough time to use PROM data during the consultation | n = 1 | n = 4 | n = 14 | n = 1 | n = 4 | 3.1 (24) | 1.0279 |

| 4% | 17% | 58% | 4% | 17% | |||

| 34. I have the opportunity to document how I have used PROM data to enhance the care and/or treatment | n = 6 | n = 2 | n = 10 | n = 3 | n = 3 | 2.7 (24) | 1.3180 |

| 25% | 8% | 42% | 13% | 13% | |||

| 36. I find that the initiative of using PROM is meaningful for my clinical practice | n = 1 | n = 2 | n = 11 | n = 6 | n = 3 | 2.0 (23) | 0.9820 |

| 4% | 9% | 48% | 26% | 13% | |||

| 37. I discuss specific patient cases with my colleagues based on PROM data | n = 3 | n = 3 | n = 13 | n = 1 | n = 3 | 2.9 (23) | 1.1246 |

| 17% | 13% | 52% | 4% | 13% | |||

| 38. I would like to learn more about how I can actively incorporate PROM data into my consultations | n = 1 | n = 2 | n = 8 | n = 9 | n = 3 | 3.4 (23) | 0.9940 |

| 4% | 9% | 35% | 39% | 13% | |||

3.2. The Qualitative Results

A total of 28 participant observations were conducted during consultations with 26 patients, involving 10 nurses and three surgeons. The observations lasted between 30 and 90 min. For an overview of participant observations, see Table 3. Ten interviews with HCPs were planned, but only nine were conducted, as one interview was cancelled due to a participant’s illness. Interviews were conducted with seven nurses and two surgeons. Each interview lasted an average of 55 min.

| Type of follow-up consultation | Patient | Age in years | Type of cancer surgical therapy | PROMs were used in the consultation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60-min outpatient nurse consultation, 4 days after surgery (T1) | P5 | 70 | Bilateral mastectomy | Yes |

| P6 | 68 | Mastectomy | No | |

| P8 | 34 | Mastectomy | No | |

| P9 | 46 | Mastectomy | Yes | |

| P13 | 65 | Breast-conserving surgery | Yes | |

| P14 | 60 | Breast-conserving surgery | Yes | |

| P18 | 64 | Mastectomy | No | |

| P19 | 66 | Mastectomy | Yes | |

| P20 | 65 | Mastectomy | No | |

| P21 | 68 | Breast-conserving surgery | No | |

| 30-min phone nurse consultation, 11 or 18 months after diagnosis (T2) | P1∗ | 57 | Breast-conserving surgery | Yes |

| P2 | 77 | Breast-conserving surgery | Yes | |

| P3∗ | 59 | Mastectomy | Yes | |

| P4 | 65 | Breast-conserving surgery | Yes | |

| P7 | 49 | Breast-conserving surgery | Yes | |

| P12 | 64 | Breast-conserving surgery | Yes | |

| P15 | 57 | Breast-conserving surgery | Yes | |

| P19 | 66 | Mastectomy | Yes | |

| P22 | 52 | Mastectomy | Yes | |

| P23 | 79 | Breast-conserving surgery | Yes | |

| 45-min outpatient nurse and surgeon consultation (T2-2) | P1∗ | 57 | Breast-conserving surgery | No |

| P3∗ | 59 | Mastectomy | No | |

| P10 | 50 | Mastectomy | No | |

| P11 | 64 | Mastectomy | No | |

| P16 | 54 | Mastectomy | Yes | |

| P17 | 78 | Bilateral mastectomy | Yes | |

| P24 | 72 | Breast-conserving surgery | Yes | |

| P25 | 34 | Breast-conserving surgery | Yes | |

- ∗Patients who were observed during two separate consultations.

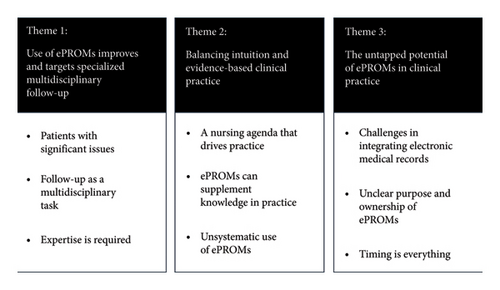

The analysis generated three overarching themes: (1) the use of ePROMs improves referrals and targets specialized multidisciplinary follow-up services; (2) balancing intuition and evidence-based clinical practice; and (3) the untapped potential of ePROMs in clinical practice (see Figure 2).

3.2.1. Use of ePROMs Improves and Targets Specialized Multidisciplinary Follow-Up

I definitely think the patients I’ve seen for follow-up based on the ePROMs, present relevant concerns. One was apologetic and unsure if it was silly of her to be there. We discussed [a possible] correction after a previous breast cancer surgery, and I reassured her that it was completely valid to talk about it. If the conclusion is that no surgery is needed, then that’s fine. The purpose is to reach some form of clarification – not all patients necessarily need surgery. (Surgeon 2)

Our job is to discuss the ePROMs with patients and explore why they requested a follow-up. Sometimes the patient just needs to talk about how she’s feeling, while other times we identify the need for a surgical assessment. In such cases, I refer them to a plastic surgeon, who will then determine if and how we can provide further help. (Nurse 2)

I do feel competent to handle the follow-up consultations. But if I had been given this responsibility a year ago, I would have lacked experience, especially with many of the reconstructions. But I’ve gained a lot of experience since then, so I’m far better prepared now. (Surgeon 2)

This highlights the importance of assigning experienced professionals to follow-up care, as nurses and surgeons emphasize that expertise is essential to address patients’ complex needs effectively.

3.2.2. Balancing Intuition and Evidence-Based Clinical Practice

I haven’t spent much time learning the ePROM system because I rely on my nursing skills. My approach is to focus on what I know my patients need, which I later learned aligns with the focus of ePROM – addressing the patient’s emotional and physical well-being, how she feels about her body after surgery, and her intimacy with her partner or herself. These are areas I’m used to explore, so I feel confident it’s the right approach. (Nurse 4)

I use ePROM to understand how the patients feel about their body image, but I believe I could sense it without it. I always have the patients look at themselves in the mirror during the consultation, which gives me a good sense of their body image. The ePROM now serves as an additional tool to confirm my observations. (Nurse 2)

I don’t use ePROMs systematically. I mostly check for low scores to identify any issues. In the second follow-up conversation, the focus is often more on the overall treatment – how their chemotherapy and radiation went. Patients tend to bring up their concerns through that discussion rather than via the ePROM, so the form isn’t very dominant. (Nurse 6)

This demonstrates the challenge of integrating intuition and traditional nursing practices with systematic, evidence-based tools like ePROMs. While nurses value their clinical judgement and experience, selectively using ePROMs as a supplementary tool entails the risk of undervaluing the potential of structured data to enhance PCC.

3.2.3. The Untapped Potential of ePROMs in Clinical Practice

If ePROMs were integrated into the electronic medical record, it would be slightly easier since you’d already be logged into the system and could find it there. But it’s not difficult to log into Redcap separately. I just think it would be easier for people to make it a routine if it was in the same system. (Surgeon 2)

ePROMs were introduced, like, [bangs fist on the table] ‘Okay, now you have to do this as well.’ We might have been more motivated if it hadn’t come at a time when so much was going on –there was COVID, and the department was being relocated. It was a chaotic time to start something new. I also think it always takes a while after introducing something for people to truly grasp its purpose. (Nurse 6)

Observations and interviews revealed that only HCPs responsible for ePROMs and patient consultations used the ePROMs despite their availability to all HCPs.

Using the ePROMs as intended – by reviewing them with the patient and focusing on their experience—would help create a person-centred approach. But honestly, there are often many other pressing concerns when the patient comes in just days after surgery. (Nurse 4)

This illustrates the untapped potential of ePROMs, suggesting that addressing timing and relevance challenges could improve their integration into clinical practice and support more PCC.

3.3. Integration From Quantitative and Qualitative Data

While the quantitative data provided insights into the overall familiarity with and experiences of person-centred practice and ePROMs, the qualitative study contributed with rigorous information on how ePROMs and PCC are perceived and utilized in clinical practice. In Table 4, the results from the quantitative and qualitative studies are integrated into metainterferences, constituting connections between the two datasets when considered together (see Table 4).

| Theme-overarching constructs | Quantitative results (survey) | Qualitative results (observations and interviews) | Metainterferences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alignment with personal beliefs and values | On average, respondents reported that they were able to perform their clinical work in line with their beliefs and values (M = 3.6, SD = 0.97), with over half of them agreeing (52%) | The nurses prioritized their values over the use of ePROMs, focussing more on the nursing agenda and experiences. In contrast, the surgeons viewed ePROMs as aligned with resource efficiency and fairness, seeing them as tools to optimize treatment while integrating the patient’s voice | Further research should explore the discrepancy between the staff’s values and beliefs and how these can be more incorporated into practice. Specialized or experienced HCPs are essential to further develop the use of ePROMs, providing a strong base for further implementation |

| Professional potential and competencies | Respondents generally agreed that they had the opportunity to employ their professional potential (M = 3.6, SD = 1.42), with 32% strongly agreeing. Likewise, they felt confident in their professional competencies to provide individual care (M = 3.77, SD = 1.22), with 44% agreeing and 28% strongly agreeing |

|

Specialized or experienced HCPs are essential for further developing the use of ePROMs providing a strong foundation for further implementation |

| Focus on patient satisfaction and quality of life | The highest mean scores were observed for questions related to insight into patient satisfaction and quality of life both scoring an average of 4.4 (SD = 0.71 and 0.77, respectively). A notable 60% of respondents strongly agreed with the relevance of these aspects | HCPs had strong insights or awareness regarding the relevance on body image issues and how these affect patient satisfaction and their overall quality of life | The high interest in patient satisfaction and quality of life supports the future work with ePROMs in the department. However, a more systematic use of ePROMs might enhance patients’ experiences of PCC |

| Engagement with patient feedback | Respondents reported actively seeking feedback about the meaning of the treatment to the patient (M = 4.0, SD = 0.95), with 40% strongly agreeing and another 36% agreeing. They also found it relevant to discuss patients’ satisfaction and quality of life after breast surgery (M = 4.1 and M = 4.2; SD = 0.90 and 1.0, respectively) | HCPs argued that in their practice, they based their approach on the patient’s situation, where they relied heavily on their experience and intuition to individualize the consultations | There is a growing interest among the HCPs about person-centred practice, including receiving feedback to inform and improve their work |

| Conditions for PCC | The average score for having the necessary terms and conditions to organize PCC was lower (M = 3.0, SD = 1.02), with 48% choosing neutral, indicating a potential for improvement in supporting individualized care pathways | Time and opportunities for using ePROMs were described as a limitation for some. Others did not feel that the terms and conditions were a limitation for working in a person-centred manner. There was an understanding that PCC would be more time-consuming | The concept of PCC and practice is still new in the department, and further knowledge of the concept might change this. Leaders should support and facilitate HCPs in this transitional process |

| Use and knowledge of ePROMs | Familiarity with the ePROM system varied. Respondents scored an average of 3.0 (SD = 1.46) when asked about their familiarity of the system, with 32% disagreeing or strongly disagreeing. Furthermore, respondents felt limited in their ability to access and integrate PRO data into consultations, reflected in mean scores of 2.7 (SD = 1.59) for accessing the data and 2.6 (SD = 1.52) for familiarizing themselves with the data | ePROMs were used only by HCPs who had direct responsibility for this and consulted patients using ePROM | Knowledge of ePROMs in clinical practice is not widely prevalent in the department, apart from a few individuals who hold specific roles |

| Time constraints | Time limitations were a concern, as indicated by a mean score of 2.7 (SD = 1.27) for having sufficient time to prepare for consultations using ePROM data. This suggests that many participants felt constrained in their ability to effectively use these data within their practice | The nurses, in particular, found it time-consuming to log into REDCap to access ePROMs. Some nurses suggested that the data should be printed on paper before the patient’s consultation to save time and ensure they had enough time to understand the ePROM | The introduction of ePROMs in the department remains a developmental concept, and the additional time required should be considered and prioritized in clinical practice |

| Impact of ePROMs on clinical practice | When asked whether ePROMs improved their treatment or care, respondents scored an average of 2.7 (SD = 1.14), with only 8% strongly agreeing. Similarly, the perceived impact of ePROMs on clinical decision-making yielded a score of 2.7 (SD = 1.25), suggesting limited enthusiasm for its current integration into practice | The nurses placed greater trust in their own professional judgement regarding what was important in the consultation, rather than actively using ePROMs. At the same time, several expressed that it took time to develop a sense of ownership in utilizing ePROMs | Knowledge of and evidence regarding the use of ePROMs should be disseminated more widely within the department to support the active use of ePROMs and evidence-based practice for the benefit of patients |

| Desire for further learning | A majority of respondents expressed interest in learning more about integrating ePROM into their patient meetings, as reflected by a mean score of 3.4 (SD = 0.99), with 39% agreeing with this statement | There was a positive attitude among HCPs towards the introduction of ePROMs and gaining ownership of their use. HCPs described themselves as open to advancing their knowledge | This indicates that the introduction of ePROMs is still in progress and that training should be continuous during the implementation of ePROMs into routine clinical practice. It also reflects a positive attitude among HCPs towards working in a continuous learning environment, as part of a university hospital |

4. Discussion

The objective of this study was to evaluate HCPs’ perspectives on the ePROM intervention for follow-up in women diagnosed with breast cancer and their opportunities for person-centred practice, to investigate HCPs’ utilization of ePROMs and to explain these findings to obtain a comprehensive understanding of how the ePROM is used in routine clinical practice.

Comparable findings regarding HCPs varied engagement with ePROMs have been reported in other surgical specialities. In orthopaedic settings, for example, surgeons perceive ePROMs as useful tools for evaluating outcomes and supporting resource allocation. In contrast, nurses and allied professionals frequently identify barriers such as time constraints, challenges in accessing digital systems and uncertainty about the clinical relevance of ePROMs [29, 30]. These findings indicate that differences in how professional groups engage with ePROMs are not limited to breast cancer care but reflect broader patterns across surgical practice. However, the context of breast cancer follow-up introduces specific complexities, including issues related to body image, psychosocial recovery and long-term survivorship. These dimensions place particular emphasis on PCC and may indicate the need for differentiated roles and approaches in the use of ePROMs.

These findings reflect the challenge of introducing ePROMs into practices that are guided by professional norms and autonomy, a challenge that has also been described in the literature [54–56]. The implementation of PROM systems has substantial implications for the autonomy of HCPs. Autonomy is crucial for HCPs as it enables them to carry out their clinical practice, fostering a sense of professional ownership and improving the overall quality of care [57, 58]. However, the introduction of ePROM systems can be perceived as a disruption to this autonomy and lead to feelings of disempowerment among HCPs who may feel that their professional judgement is being undermined by standardized measures imposed by healthcare administrators or policymakers [59]. Moreover, the use of ePROMs is dependent upon the self-efficacy of HCPs in utilizing PROMs within clinical practice. Self-efficacy, defined as an individual’s belief in their ability to execute behaviours necessary to produce specific performance attainments, plays a critical role in how HCPs engage with new digitalized concepts as ePROMs [60, 61]. Studies indicate that many HCPs feel inadequately prepared to integrate new digital data into their workflows, leading to resistance or ineffective use [60, 61].

The tension between experience-based approaches and evidence-based tools like ePROMs was also identified in other recent studies where HCPs often rely on intuition and professional judgement [62, 63]. Similarly to our study, the challenges in the implementation of PROMs were attributed to a lack of organizational readiness. This tension presents a significant challenge, as reliance on intuition and professional judgement can result in inconsistent patient care, leaving some patients with unmet needs. It also fosters a preference for experience-based practice that may not align with the best available evidence, ultimately compromising the quality and safety of care [64].

The findings also relate to shared decision-making, which is defined as ‘a collaborative approach by which, in partnership with their clinician, patients are encouraged to think about the available care options and the likely benefits and harms of each, to communicate their preferences, and help select the best course of action that fits these’ [65]. While ePROMs have the potential to support shared decision-making by bringing patient experiences and preferences into consultations [66, 67], this potential was only partially realized in practice. Nurses’ reliance on intuition and the lack of systematic use of ePROMs limited the opportunity for structured, collaborative discussions with patients. Strengthening the integration of ePROMs could therefore enhance shared decision-making by enabling more informed and person-centred clinical conversations. However, there are recommendations on how to put evidence, as ePROMs represent, into practice. Chays-Amania et al. [68] and Hu et al. [69] both emphasize the necessity of a clear organizational strategy for implementing and reinforcing evidence-based working, with Hu et al. highlighting the importance of an organizational culture and vision as precursors to such a strategy [69].

The department in which this study was conducted faced several challenges related to organizational and cultural readiness during the study period. This could be understood as a crisis, defined as ‘a specific, unexpected, non-routine event or series of events that creates high levels of uncertainty and a significant or perceived threat to high-priority goals’ [70]. First, the department was characterized by the hospital’s ongoing transition into a university hospital including the development of an emerging academic environment. The mindset and self-perception of HCPs at a university hospital appear to influence outcomes. Operating as a university hospital entails conducting research at the highest international level, educating HCPs and fostering forums for professional learning and knowledge sharing [71]. However, the neutral responses by the majority in Table 2, Question 19, regarding whether the culture supports research and clinical practice, suggest that the department’s identity as a university unit is not fully embedded in its mindset. Second, it was significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, which reduced its capacity [72]. Finally, the department underwent a relocation process, which involved the merging of departments from two separate locations into a single site. In times of crisis, organizational hierarchies can become disrupted, leaving employees to self-manage tasks and priorities as leaders focus on urgent demands. This stagnates efforts to cultivate and sustain departmental culture, increasing reliance on individual interpretations of best practices and routine behaviours [70]. Among nurses, a long-standing intuitive, constructivist paradigm in handling clinical challenges may have contributed to a conscious or unconscious rejection of tools like BREAST-Q, perceived as redundant to their established knowledge and practices. Findings also highlight a lack of strategic involvement in the implementation process, with BREAST-Q perceived as a mandatory task rather than a meaningful, participatory initiative. From a psychodynamic perspective, this rejection could reflect a conscious or unconscious dismissal of BREAST-Q, rooted in the belief that it adds no value, as the group perceives they already address its insights independently [73]. These factors have likely all influenced both the ePROM intervention and its implementation. However, there was a notably high participation rate in ePROMs among patients, which underscores their engagement with the intervention [74].

In the broader context of healthcare, the integration of ePROMs is increasingly recognized as essential for improving the quality of care and enhancing patient outcomes [55, 75]. However, studies highlight challenges with ePROMs, including data quality issues, patient-reporting biases and implementation burdens, emphasizing the need for a nuanced adoption approach [76]. The World Health Organization (2021) underscores the importance of including patient perspectives in treatment evaluation, especially in areas such as breast cancer, where quality of life and body image play crucial roles in post-treatment recovery [3]. That being said, as this study demonstrates, the successful incorporation of ePROMs is complex and requires more than teaching and technical implementation—it demands alignment with the values, experiences and workflows of HCPs and that the organization is prepared for change [77]. The differences observed between HCPs in their engagement with ePROMs reflect the complexities of clinical practice. Nurses’ focus on their values and patient care experience at the expense of systematic ePROM use underscores the importance of understanding healthcare providers’ perspectives and values when implementing new technologies, as found in other research [78].

The study found that HCPs valued ePROMs as a useful tool for patient follow-up and resource management. Most HCPs expressed an interest in integrating quality-of-life outcomes into their practice and learning more about ePROMs, presenting a future opportunity to enhance PCC by aligning future ePROM implementation with HCPs’ values, as supported by Dyb et al. [78].

Compared to previous research, this study highlights nurses’ ambivalence towards systematic ePROM use, driven by reliance on intuition over data. While earlier studies focus on patient perspectives or general oncology, this study adds insights into how organizational context, timing and professional autonomy influence ePROM use in surgical breast cancer follow-up. Implications for future practice are that leadership and implementation strategies must prioritize supporting HCPs in balancing their autonomy with evidence-based practice. Furthermore, fostering HCPs’ self-efficacy within an encouraging learning environment is critical to support the adoption of ePROMs for person-centred clinical practice [77, 79, 80]. These findings also call for policy-level responses including specialty-specific and measurable actions. The authors recommend (1) the technical integration of the BREAST-Q instrument into the electronic medical record system to enable real-time access for clinicians during T2 and T2-2 consultations; (2) the development of mandatory training programmes and ongoing professional development focussed on the clinical interpretation and application of BREAST-Q data; and (3) the appointment of local ePROM ‘champions’ among nurses and surgeons to strengthen departmental ownership, facilitate peer learning and support implementation. Furthermore, the use of ePROMs should be routinely monitored through quality audits or utilization metrics to support alignment with PCC objectives.

4.1. Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, the sample size, particularly for the interviews (n = 10), was relatively small, which may limit the transferability of the findings. However, the participants represented key stakeholders who had experience with the ePROMs intervention, providing valuable insights into its use in clinical practice. Additionally, the survey used in the study was not completely validated, having only undergone face validation among the researchers and department staff. This limitation may compromise the survey’s validity and reliability, potentially affecting the generalizability of the findings [46]. The relatively low response rate, with only 31% of the invited participants completing the survey, may limit the generalizability of the findings. The low response rates may also have introduced nonresponse bias, as HCPs who chose not to participate may differ in their attitudes, experiences, or familiarity with ePROMs. This could lead to skewed results by portraying a more engaged perspective on ePROM implementation than is representative of the broader HCP team. Furthermore, because the nonrespondents included a higher proportion of physicians (19 compared to 8 respondents) and a broader age range, important perspectives may be missing from these groups. This encourages reflection on key lessons, such as understanding the reasons behind the low response rate and identifying strategies to improve participation in future research. Possible approaches in future studies could include targeted reminders, greater involvement of departmental leadership and modest nonmonetary incentives. Additionally, qualitative follow-up with nonrespondents might help uncover reasons for nonparticipation and provide insights into perspectives absent from the current findings. These considerations also point to a broader need to explore how the implementation of ePROMs in clinical practice can be further supported and sustained.

The findings from this single-centre study primarily contribute to the practices within this particular clinical setting. While the insights gained are valuable for enhancing the integration of ePROMs in this context, the results may be less generalizable beyond the localized clinical environment, as they reflect the unique dynamics, workflows and professional cultures of the department studied. Moreover, the single-centre design limits the consideration of potential cultural and institutional differences across healthcare settings, which may affect the broader applicability of the findings However, there may be some transferability of the findings to similar clinical settings that share comparable organizational structures, patient populations or implementation challenges.

5. Conclusion

This study explored HCPs’ opportunities for and their perspectives on the use of ePROMs in the surgical follow-up of women diagnosed with breast cancer. The findings highlight the potential of ePROMs to enhance PCC by systematically incorporating patient experiences into clinical practice. Despite general agreement on the value of ePROMs for improving quality of care and patient outcomes, significant barriers to their use were identified, including time constraints, technical integration challenges and a reliance on intuition over evidence-based data. This study contributes to knowledge on challenges and opportunities associated with integrating ePROMs into surgical follow-up care, underscoring the need for tailored strategies to promote person-centred practice with ePROMs in breast cancer management [81, 82].

Implications for practice suggest that future efforts should focus on aligning ePROM use with HCPs’ values and practices, while ensuring that organizational readiness and resource allocation support the sustainable integration of ePROMs into routine clinical practice. To achieve this, future pathways should prioritize strengthening HCPs’ self-efficacy in using ePROMs, support seamless access to PROM data in clinical workflows, support a person-centred practice culture and ensure leadership engagement to align clinical autonomy with evidence-based approaches.

Nomenclature

-

- HCP

-

- Healthcare professional

-

- ePROM

-

- Electronic patient-reported outcome measures

-

- PCC

-

- Person-centred care

Ethics Statement

The study was approved by the Scientific Ethics Review Committee of the Zealand Region of Denmark (protocol number SJ-914, EMN-2021-01530).

Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Stine Thestrup Hansen: writing – original draft, visualization, validation, supervision, software, resources, project administration, methodology, investigation, funding acquisition, formal analysis, data curation and conceptualization.

Karin Piil and Lone Jørgensen: writing and review–editing, visualization, validation, supervision, methodology, investigation, formal analysis and conceptualization.

Volker-Jürgen Schmidt: funding acquisition and conceptualization.

Lotte Gebhard Ørsted: writing and review–editing, resources, project management and funding acquisition.

Funding

This study was funded by Zealand University Hospital, Denmark, as part of the National Cancer Plan 4, 20-082, 2020.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the department’s nurses and surgeons for sharing their experiences and for contributing their clinical practice to this research.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.