Adopting a Dyadic Approach to Treating Chronic Cancer-Related Fatigue: A Mixed Methods Study to Assess Patients’ and Partners’ Needs, Benefits, Barriers and Preferences

Abstract

Introduction: Chronic cancer-related fatigue (CCRF) is a common symptom among patients. Current therapies target the patient alone, while evidence suggests that targeting the dyad might be more beneficial.

Method: Using a mixed methods design, we conducted two studies that together aimed to provide more insight into the needs, benefits, barriers and preferences regarding a couples therapy for CCRF. In a qualitative study, we conducted focus groups and semi-structured interviews with a purposive sample of 10 patients and 10 partners with experience of CCRF care, followed by thematic analysis. In a subsequent quantitative study, a convenience sample of patients (n = 172) and partners (n = 55) completed an online survey developed based on the qualitative findings.

Results: In the qualitative study, both patients and partners expressed that a couples therapy could help them. Perceived benefits included empowerment of partners to support patients and improved couples communication. In the online survey, the need for a dyadic approach to CCRF therapy was confirmed by both patients (39%) and partners (91%). The benefits reported by most patients and partners were that partners could get attention for their own problems related to the patients’ cancer and fatigue (patients: 72%, partners: 86%) and receive advice on coping with fatigue (66% and 90%, respectively). Participants in both studies identified barriers, such as a fear of burdening partners with a couples therapy (50%). Partner involvement was considered desirable for most therapy elements (e.g., psychoeducation, contact with the therapist, exercises and relapse prevention). Yet, individual preferences varied widely.

Conclusion: Results of both studies support the potential acceptability of a couples therapy for CCRF among patients and partners. Based on divergent preferences, we determined that a couples therapy must provide flexibility regarding the degree, intensity and type of partner involvement. Dyadic psychoeducation can be used as a solid starting point to manage expectations and get relief from perceived barriers.

1. Introduction

Chronic cancer-related fatigue (CCRF) is a common symptom among patients with cancer [1], defined by The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) as ‘a distressing, persistent, subjective sense of physical, emotional and/or cognitive tiredness or exhaustion related to cancer or cancer treatment, that is not proportional to recent activity and interferes with usual functioning’ [2]. Its aetiology is likely multifactorial and complex, involving several biological and psychological factors [3, 4]. While psychological as well as exercise therapies have shown to effectively alleviate patients’ fatigue [5–7], they are directed at the patient alone, despite growing evidence for the importance of involving patients’ partners in the therapy (i.e., a dyadic approach) [8–12].

Patients deal with cancer and CCRF in the context of their close relationships [13–15]. That is, close others, in particular intimate partners, are likely to affect patients’ fatigue outcomes. For example, in a daily diary study, ruminative conversations between patients and their partners were found to be associated with more daily fatigue in patients [13]. Although both facilitative (e.g., encouraging the patient to be active) and solicitous (e.g., taking over patients’ chores) partner behaviours were positively associated with daily relationship satisfaction in patients, patients experienced less interference of fatigue with their activities on days when their partners showed more facilitative behaviours but less solicitous behaviours [14]. This suggests that therapies that encourage adaptive daily interactions between couple members have the potential to contribute to better fatigue outcomes for the patient. Moreover, the degree to which patients benefit from psychological therapy for fatigue appears to be related to partner and relationship variables. For example, a study among patients with chronic fatigue syndrome showed that high levels of fatigue in partners and relationship dissatisfaction of patients are associated with less improvement in fatigue severity after cognitive behavioural therapy [15]. This again suggests that involving the partner in the therapy may be beneficial for the patient. As the cancer experience, including CCRF, can also negatively impact intimate partners [16–19], such a couples therapy may as well be beneficial for partners. That is, a better understanding of how to deal with fatigue as a couple and an improvement of fatigue outcomes in the patient may also alleviate partner distress and improve the couple’s relationship.

However, we do not know whether patients and their partners would find a couples therapy acceptable, and what their preferences for such a therapy would be. We previously demonstrated the effectiveness of a 9-week, web-based, therapist-guided, individual mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (i.e., individual eMBCT) that was specifically designed to reduce CCRF [20]. The individual therapy could be adapted and offered as a couples therapy in which both patients and partners participate. The current paper presents two studies that together aim to provide more insight into the needs, benefits, barriers and preferences regarding such a couples therapy for CCRF.

2. Aims Study 1

Study 1 aimed to investigate (1) the perceived needs, benefits and barriers of patients with CCRF and their partners with respect to participation in a couples eMBCT for CCRF and (2) the preferences they have regarding involving their partner and being involved, respectively, in a couples eMBCT for CCRF.

3. Method Study 1

3.1. Study Design

In this qualitative study, we conducted focus groups and semi-structured interviews with persons who had followed the individually oriented eMBCT for CCRF and partners of these persons. We will refer to the participants with (former) CCRF as ‘patients.’

3.2. Participants

Participants were recruited via the Helen Dowling Institute (HDI), a specialised mental healthcare centre for patients with cancer and their close others. Patients (and partners) were eligible if they (or their partner) had received eMBCT for CCRF less than 24 months ago and had completed medical cancer treatment at least 3 months ago, had a good command of the Dutch language, were aged 18 years or older and had agreed to participate in the research. It was not required that both members of a couple participated. We purposively sampled both patients (and partners of patients) who had and had not completed the individual therapy and who indicated they had and had not benefited from it. Also, we aimed to include men as well as women and patients with different tumour types.

3.3. Procedure and Measures

Participants could choose to take part in either a focus group (for patients and partners separately) or an individual interview between December 2020 and June 2021. After providing informed consent, information on relevant sociodemographic (i.e., age, sex, marital status, relationship duration and relation satisfaction) and clinical characteristics (i.e., cancer type and treatment) was obtained. Due to preventative COVID-19 measures, all focus groups took place via secure online video consulting (Windows Teams). They were moderated by two researchers (SvD and WS) and lasted on average 1.5 h. Depending on participants’ preferences, individual interviews (administered by SvD) could be arranged either through online video consulting or by phone (on average 45 min). Audio and video recordings of the focus groups and interviews were transcribed verbatim and anonymised.

Two semi-structured interview guides were developed to lead the conversations, that is, one for patients and one for partners (see Supporting file 1). The guide for patients was pretested with help from an expert by experience (WS) and contained questions about (a) experiences with CCRF and the individual eMBCT; (b) experiences with partner support and involvement during CCRF and the individual eMBCT; (c) needs, benefits and barriers regarding participating in a couples eMBCT; and (d) specific preferences for involving the partner in such a couples eMBCT. The guide for partners was based on the patient version and dealt with (a) experienced impact of cancer and CCRF on the partner’s personal life and intimate relationship; (b) memories, (indirect) experiences and involvement with respect to the individual eMBCT followed by the patient; (c) needs, benefits and barriers regarding participating in a professional couples eMBCT; and (d) specific preferences for such a couples eMBCT, including own involvement and support needs related to CCRF.

3.4. Ethics

Both study 1 and study 2 have been approved by the medical ethics committee of the University Medical Centre Groningen (registration number 20200514). We conducted the studies according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (October 2013). We followed the reporting standards for qualitative research (RSQR) [21] for the reporting of study 1 and the strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines [22, 23] for the reporting of both study 1 and study 2 (see Supporting files 2 and 3, respectively).

3.5. Data Analysis

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were summarised using descriptive statistics, see the sample section for a summary or Supporting file 3 for all details. We adopted an iterative approach for collecting and analysing qualitative focus group and interview data, starting the analyses when recruitment and data collection were still ongoing and could thus be adjusted and supplemented based on preliminary findings. Interviews were continued until thematic saturation was reached for all core topics of the interview guides. We performed inductive thematic analyses [24], yet making sure that the core topics of the interview guides were captured in the main codes. Two researchers (SvD and RvW) independently read the transcripts of the first four focus groups (n = 1) and interviews with patients (n = 2) and partners (n = 1) thoroughly to get familiar with the data. Subsequently, they assigned initial codes (open coding) that were discussed until reaching consensus and, thereupon, collated into potential themes. Emergent themes were then reviewed and organised into a preliminary coding scheme (axial coding). This coding scheme served as a base for the analysis of the remaining focus groups and interviews (selective coding), which was performed by one researcher (SvD) and checked by another (RvW). Through constant comparative analysis [24], experiences with CCRF and eMBCT and acceptability and preferences regarding a couples eMBCT were compared within and between participants, patients and partners, and couples. Analytical and qualitative rigour were enhanced by constructive mutual evaluation and feedback by the researchers after each focus group, a reflexive attitude during both data collection and data analysis and the exploration of divergent views during the analyses. Furthermore, codes, themes, their interpretations and the clustering of quotes were regularly discussed among members of the research team, who have backgrounds in psychology, psycho-oncology, epidemiology and social sciences, and clinical experience as well as experience as a patient.

4. Results Study 1

4.1. Sample

In both groups (i.e., patients and partners), we conducted one focus group with three participants each and seven individual interviews (with the remaining participants). All patients and partners that were approached participated, resulting in a sample of 20 participants, including seven couples. We interviewed 10 patients, who were mostly women (n = 7) and had a mean age of 52 years (range: 38–61 years). Seven of these patients had completed all sessions of the individual eMBCT (and three had not). We included 10 partners, who were mostly men (n = 6) and had a mean age of 51 years (range: 38–63 years). Two of these partners had received mental healthcare at the HDI. Patients and partners had either themselves or through their partner been confronted with chronic fatigue related to seven different types of cancer (i.e., breast, cervix, skin, kidney, lung, bladder, intestines; mostly breast), which had been medically treated in various ways (e.g., chemotherapy, surgery, radiotherapy, hormone therapy and immunotherapy). Relationship duration varied from 2.5 to 38 years; one partner was widowed. Experiences with partner involvement during individual eMBCT varied from simply knowing that the patient was following therapy to actively reading and thinking along and participating in exercises and assignments.

4.1.1. Research Aim 1: Perceived Needs, Benefits and Barriers of Patients With CCRF and Their Partners With Respect to Participation in a Couples eMBCT for CCRF

4.1.1.1. Perceived Need of Participating in a Couples eMBCT for CCRF

Patients and partners almost unanimously indicated a need to participate in a couples eMBCT for CCRF. Only one patient was very clear and decided that she would not be interested in such a couples therapy. Thematic analysis further identified two themes (i.e., benefits and barriers) that were divided into several subthemes. Table 1 presents an overview and illustrative quotes.

| Perceived benefits of participating in a couples eMBCT for CCRF | |

|---|---|

|

|

| … save patients the effort and energy of having to involve their partner themselves | ‘My wife was interested in it (eMBCT) and she can think along very well. But when I was really tired, I didn’t feel like talking about it. I think that would have been even easier in a couples eMBCT.’–Pt08 (Pr06) |

| ‘It (professionally involving the partner in the therapy) will have huge additional benefits (…). Otherwise, she (patient) has to explain everything to me, while, actually, that is a waste of energy.’–Pr04 (Pt04) | |

| … help patients to communicate and explain fatigue experiences to partner | ‘Involving the partner would have been a really big plus for me. Since I hadn’t figured out yet how to include others in this. I couldn’t describe it like (name of therapist).’–Pt04 (Pr04) |

| … help partners to understand and anticipate CCRF | ‘She (the patient) could tell me she was tired, but there are so many different layers of fatigue underneath ()(…). And from the outside I couldn’t see that. (…) To really grasp the perceptions and energy level of your partner you need more expert information.’–Pr01 (Pt01) |

| … enable partners to increase patients’ insight into their fatigue experiences and behaviours through reflection | ‘In certain assignments, I had to describe my behaviour or my feelings and thoughts and I struggled with this. For instance with conflict avoidance. If my partner would have been involved, I could have asked him: “How do you see it?” By articulating it differently, he could have helped me gaining insight into myself.’–Pt01 (Pr01) |

| ‘I was involved in the session in which (name patient) had to indicate her boundaries. And then it turned out that I often see much earlier than she does herself that things are going wrong with her. (…) I think that’s a good example of how the partner can play a very important role in the therapy. To look at it from a distance, from the side, so to speak, and to name it, while she (name patient) may not yet be aware of it.’–Pr01 (Pt01) | |

| … help partners to find and adopt appropriate support roles, thus increasing their self-efficacy and the positive impact of their support | ‘I was not always sure if I was doing the right thing (during CCRF and individual eMBCT), if I was choosing the right words or… I actually felt a bit like an outsider who interfered. (…) If you’re part of the treatment, you’re like a partner in the course. Then you can actually refer to things you’ve heard, (…), do it as a kind of tandem. You can coach each other a bit.’–Pr03 (Pt03) |

| ‘If I know what exercises he (patient) needs to do, I can encourage him to do them. (…) And I would also like to know when he needs to rest, so that I can give him a break instead of encouraging him. That’s why I think couples therapy will be useful.’–Pr07 (Pt09) | |

|

|

| … pay attention to the problems the partner encounters due to the cancer and/or CCRF | ‘I really thought “nobody understands me.” (…) And I understand that they didn’t understand me, but still, I was alone in this. (…) A lot has changed in our (partners’) lives too. There is a need to talk about that.’–Pr06 (Pt08) |

| ‘What we experienced quite a bit during the process: it’s all about you (as a patient). The partner is very quickly forgotten, also by the (social) environment. (…) I think it’s good to involve the partner a little more, especially because for him it may be even harder than for the one who is chronically fatigued.’–Pt06 | |

|

|

| … explicitly discuss the impact of CCRF on the relationship and the couple’s communication (thereby breaking or reversing a downward spiral of individual fatigue-related problems that fuel relationship problems, which in turn exacerbate fatigue-related problems, etc.) | ‘Getting a better understanding of the impact and how best to deal with that together, so that you can find a new way of working together in your relationship. Being able to do that together in the therapy would be especially valuable, I think.’–Pr01 (Pt01) |

| ‘I (partner) also have problems with you (patient) having this (CCRF). And I need to be able to talk about this to you. (…). However, if you (as a couple) don’t talk about this properly… I can well imagine that a lot of relationships end this way. That she (patient) will interpret it the wrong way. (…). Bounce the ball back like, “Oh, so you’re the victim here? So you think you suffer at all?!” And then she (patient) feels guilty, or no longer shares anything with me, just withdraws. Professional guidance would be useful.’–Pr05 (Pt07) | |

| ‘Relationship therapy was not necessary for us. But that doesn’t mean that the things we’ve just discussed (about the impact of CCRF on the intimate relationship) could have been very helpful. That might prevent other couples from breaking up.’–Pt03 (Pr03) | |

| ‘Normally, when something sad happens, we (patient and partner) always solve it together, by talking and doing. And now (during CCRF and eMBCT), somehow we couldn’t. I found that very difficult. (…) Someone else (in couples eMBCT) has to show you that you are not communicating well.’–Pr09 | |

| Potential barriers to participating in a couples eMBCT for CCRF | |

| Negative assumptions about the partner’s interest in a couples therapy | ‘I didn’t tell him (the partner) much about the therapy, because I suspected that he would find it soft.’–Pt03 (Pr03) |

| ‘I didn’t really know what was going on (during eMBCT). (…) I wasn’t going to him (the patient) ask about that. Because I was already keeping after him so much. And also because we had a good relationship, so if he had wanted to tell things, he would have told them.’–Pr02 | |

| ‘She (the patient) actually told me very little about it (eMBCT). And I’ve never really asked about it, because I think it’s often personal things that you discuss with a therapist. And yes, I was like “if you’d like to tell me, please, I am all ears,” but I was not going to ask for it.’–Pr03 (Pt03) | |

| Hesitation among partners to ask for and accept support for own problems related to CCRF | ‘Sometimes, you feel super guilty when you say: “But what about me?” Because I’m not the one who has that (CCRF). Yet, I suffer from it as well. But I don’t want to put myself out there so selfishly.’–Pr05 (Pt07) |

| Concerns or assumption that partner, or patient and partner together, would lack time and/or energy to participate | ‘It (the eMBCT) took quite a lot of time and effort. And she (the partner) was busy providing informal care for her mother. So it (involvement in a couples eMBCT) might have been more of a burden to her.’–Pt02 |

| ‘During that therapy (individual eMBCT) we had such an intense time, also with the children. I don’t really know what else I could have given her other than an occasional listening ear and the space to carry on. (…). Now I could do more, but not at that time.’–Pr08 | |

| Concerns about reduced/lost focus on patient fatigue | ‘The therapy (eMBCT) was focused on fatigue symptoms. However, he (the partner) didn’t suffer from fatigue. So if you were to involve the partner in the same way (in a couples eMBCT), you might get a completely different kind of therapy. Then you will miss the point.’–Pt04 (Pr04) |

| Preference to work on CCRF-related problems independently or with peers rather than with partner | ‘It is helpful to talk to people who have been through the same thing as you. But at home, they don’t know what you’re going through. And that’s why I think you should do this alone. And with other patients.’–Pt05 |

| ‘What I might have needed even more (than a couples eMBCT) is a partner group. To talk to partners who were in the same boat.’–Pr02 | |

| Between-partner differences in skills, abilities, manners, experiences and/or preferences that were perceived as insurmountable and impeding | ‘He (the partner) might start saying: “You shouldn’t think like this, but you should think like this.” But that’s his way of thinking, not mine. (…) Reading and understanding a question might take me 30 seconds longer than it would take him. (…) That’s the difference between his level of thinking and mine. (…) It doesn’t bother us in everyday life because we can talk about anything. But when it comes to this (eMBCT), I say, “I’ll do it my way.’–Pt05 |

| ‘I would like that (couples eMBCT) very much, but it depends on the attitude he (the partner) participates with. (…) He has a very caring and very loving side, but also a strict superego. If the superego takes over, I have a problem with that. (…) So if his attitude is like: “Hey, I’ll help you, you should be able to do this too, you need to train,” that will do me no good at all.”–Pt03 (Pr03) | |

| Fear of increased tension in the relationship and/or a lack of clarity about patient and partner roles and responsibilities during couples eMBCT | ‘The tricky thing is that as partner, sometimes, you are much too close to give your opinion on things. That sounds a bit crazy, but I find that challenging. (…) On the one hand, you want to encourage someone (your partner) to do things, but (on the other hand) you also need to accept what has happened (to your partner) and be a partner, not the therapist. It’s hard to find a balance in that. (…) It’s not like it was, you’re not the same team anymore.’–Pr06 (Pt08) |

| Concerns about social desirability and lack of openness (often prompted by fear of burdening the other) | ‘What could be a drawback, perhaps, is that they (patient and partner) might then (in couples eMBCT) both give socially desirable answers to avoid hurting one or the other, which doesn’t help for either of them.’–Pt07 (Pr05) |

4.1.1.2. Perceived Benefits of Participating in a Couples eMBCT for CCRF

4.1.1.2.1. Benefits for Supporting Patients in Coping With CCRF and Its Therapy

One of the main perceived benefits was that a couples therapy would empower the partner to support the patient in coping with the fatigue and its therapy. In this regard, patients and partners often referred to their positive as well as negative experiences with partner support during CCRF and the individual eMBCT. Several patients indicated that trying to involve their partner in the individual eMBCT had cost them a lot of energy, while their energy had already been very limited and the eMBCT itself also took time and energy. Couples therapy could have helped them to involve their partner.

Furthermore, some patients mentioned that, especially at the beginning of their eMBCT, they had not yet found the words to describe their fatigue experiences and had still been too preoccupied with their own personal process of gaining insight and acceptance to effectively communicate these experiences to their partner. Couples eMBCT could thus have helped patients to make their partner understand what they had been going through in their CCRF and eMBCT process. Partners also expressed a need for professional guidance in understanding the patient’s fatigue. Without guidance, this understanding had sometimes been hampered by their experience that they could not see the fatigue from the outside and could not anticipate it either.

During the individual eMBCT, some partners’ hesitation and insecurity about their supportive role had further increased due to negative consequences of self-initiated attempts to be supportive. Partners expected that a couples therapy would have helped them to find out what support roles would and would not work, and to increase the positive impact of their support.

4.1.1.2.2. Benefits for Supporting Partners in Coping With CCRF-Related Problems

Another perceived benefit of the couples therapy was that it could potentially not only serve patients but also partners as the latter also need and deserve attention for the problems they experience as a consequence of the patient’s fatigue. Indeed, partners indicated that they suffer from fatigue-related problems, such as emotional problems, a high caregiver burden and a lack of recognition from their social environment. Partners, but patients maybe even more, opined that currently, there still is too little attention for partners in the fatigue process and treatment trajectory. However, not all partners we interviewed wanted a couples therapy to address their own problems.

4.1.1.2.3. Benefits for the Intimate Relationship

Adopting a dyadic approach to treating CCRF might also benefit the intimate relationship between the patient and partner. Fatigue was clearly experienced to not merely impact the patient and partner individually but also together in their intimate relationship. Some participants described a downward spiral of fatigue-related problems causing or exacerbating relationship problems, which in turn further debilitated the individual well-being of both partners. Besides targeting the relationship indirectly (i.e., by addressing the partner’s role and opportunities in supporting the patient, as well as the partner’s own CCRF-related problems), a couples eMBCT could explicitly discuss the impact of fatigue on the relationship and the couple’s communication about CCRF. This could potentially break the downward spiral between individual fatigue-related problems and relationship problems.

4.1.1.3. Potential Barriers to Participating in a Couples eMBCT for CCRF

Despite most patients’ needs to receive and partners’ wishes to provide support during the individual eMBCT, some partners had barely been involved, for reasons that can be regarded as barriers to participation in a couples therapy, as described below.

4.1.1.3.1. Negative Assumptions About the Partner’s Interest in the Therapy

Some patients had not even considered asking their partner to become involved, because they had assumed that the partner would not understand the fatigue or would not want to be involved anyway. Among several partners, similar yet opposite reasoning had also posed a barrier towards getting involved. That is, they had assumed that the patient would not want them to be engaged. Some of them had not asked about the individual eMBCT because they did not want to intrude or wanted to give the patient space to share only what he/she wanted to share.

4.1.1.3.2. Other Barriers

Various partners indicated that they found it hard to ask for and accept support for themselves. Other barriers to joint participation in a couples therapy were: the assumption or concerns that the partner, or the patient and partner together, would lack time or energy to participate; concerns about reduced or lost focus on patient fatigue; a preference to work on CCRF-related problems independently or with peers rather than with the partner; between-partner differences in skills, abilities, experiences or preferences that were perceived as insurmountable and impeding; a fear of increased tension in the relationship or lack of clarity about patient and partner roles and responsibilities during eMBCT; and concerns about social desirability and lack of openness (often prompted by fear of burdening the other).

What constituted a barrier for some participants was put forward by others as a potential benefit of a couples eMBCT because couples therapy could provide an opportunity to address and perhaps even resolve the issue of concern. For example, one patient suggested that a couples eMBCT might encourage partners to accept the professional help they wanted by acknowledging their potential need for professional help and discussing any possible concerns about burdening the patient with their own problems.

4.2. Research Aim 2: Preferences for Involving Partners in a Couples eMBCT for CCRF

The focus groups and interviews with patients and partners elucidated a wide variety of preferences regarding when, how and with what intensity to involve the partner in a couples eMBCT. Table 2 provides illustrative quotes on these (divergent) preferences, categorised by therapeutic activity.

Psychoeducation for the partner This should address … |

|

|---|---|

| … CCRF and how to deal with it | ‘I think it (couple eMBCT) should include psychoeducation directed at the partner, (…). Because I missed that. (…) It helps you (as a partner) to understand your partner (i.e., the patient), and that will help him or her, but you may also be able to help yourself with it.’–Pr08 |

| … the therapy: content, goals and expectations | ‘I would like information about what the therapy can achieve. Otherwise it’s like Pandora’s box: “we’re going to do a few tricks on the internet and then she’ll be less tired.’–Pr04 (Pt04) |

|

|

| … constitution of consultations (joint and/or private consultation) | ‘I would have liked him (the partner) to actually be part of the conversation with the therapist, and not just hear a summary from me afterwards. A kind of three-way conversation would have been nice.’–Pt07 (Pr05) |

| ‘I think I would prefer to be alone with the therapist. Because it’s mostly my problem and I still have to do it myself. (…) But maybe… look… I don’t know if… if she would have been involved, that might have had a positive impact. But I don’t think I missed it (in the individual eMBCT).’–Pt08 (Pr06) | |

| … the frequency and timing of contact with the therapist | ‘At the start of such an intensive process (eMBCT), I would have liked a joint initial consultation with the therapist. And a joint final interview and maybe also an interim evaluation through Teams if necessary.’–Pr04 (Pt04) |

| ‘I think it might be good for the partner to gain some more insight into the therapy. It’s not that he has to get involved in every consultation, every week. I don’t think that’s necessary either.’–Pt06 | |

|

|

| … provide the therapist with additional valuable information about the patient | ‘We (patients) had to fill in some kind of form beforehand, a questionnaire, and that might also be useful… to let the partner complete that as well, about the patient.’–Pt06 |

| … determine what role the partner could potentially and ideally play within the therapy | ‘Yes, so then (if patient and partner do the intake with the therapist together) you can discuss and enter the therapy together: (…) how do you both see that, (…) and how can you together make that work?’–Pt10 (Pr10) |

|

|

| … joint and/or independent performance | ‘He absolutely does not have to participate in the relaxation exercises. In fact, I prefer to do those by myself. Then I can focus inwardly.’–Pt07 (Pr05) |

| ‘What might help me is an exercise for which you need two people. So that you oblige each other.’–Pt09 (Pr07) | |

| … types of exercises and assignmentsa | • Sensory exercises; Doing fun things (together: ‘You (as patient) fall back into your old patterns very quickly. And I think you can prevent that a little bit better together (as couple) than by yourself, by stimulating each other to find more relaxation. (…) Taking a walk around more often and enjoying the surroundings, for example, and doing those sensory exercises together then.’–Pt06 |

| • Meditation/Relaxation exercises: ‘Participate in such a meditation for a while. That …, those were rays of hope. Because then you are connected in something else for a while. Just a moment of calm before you have to go on again.’–Pr02 | |

| ‘Well um, parts like meditation and mindfulness and stuff, that’s not my thing. (…) I don’t feel really comfortable with that. I get the point of it, but it doesn’t work for me. I’d much rather listen to Status Quo or the Golden Earring, that actually makes me calmer and happier than really going inward.’–Pr03 (Pt03) | |

| • Planning and organisation exercises; Communication exercises: ‘The “should-I-do-this-now?” rule, do you think you should do it now and can you delegate it, (…) that could be an assignment in which the partner is involved. (…). Because of course, that also affects your partner.’–Pt07 (Pr05) | |

| ‘Um, for me it is difficult that (name patient) doesn’t want to plan anything, since he doesn’t know how he’s going to feel at a later moment. So learning to plan together would have helped me.’–Pr07 (Pt09) | |

| ‘I would like it (a couple eMBCT) to be about the expectations you (and your partner) have back and forth. And about guilt. Because I often felt guilty towards (name partner). So many years “I’m too tired, no, I don’t feel like…” Often on birthdays, when your partner is having a great time, (…), and you want to go home. (…) How do you talk about that? Maybe you can develop a conversation tool.’–Pt01 (Pr01) | |

- aMentioned: sensory exercises, concentration exercises, meditation/relaxation exercises, doing fun things (together), physical activities, planning and organisation exercises, communication exercises, drafting a relapse prevention plan.

4.2.1. Psychoeducation for the Partner

Psychoeducation for the partner was considered desirable by almost all patients and partners. This should include information about CCRF and how to deal with it. In addition, it should cover the content, goals and expectations of the couples eMBCT.

4.2.2. Participation of the Partner in Contact With the Therapist

Most patients and partners also favoured partner participation in contact with the therapist. Participants had different preferences regarding joint and/or private consultations and the frequency and timing of contact with the therapist.

4.2.3. Partner Involvement in Intake and Screening

Some participants felt it would be a good idea to involve the partner straight from the intake; this would provide the therapist with additional valuable information about the patient and also provide an opportunity for the patient and the partner to coordinate together with the therapist what role the partner could potentially and ideally play in the therapy.

4.2.4. Participation of the Partner in Exercises, Assignments and Relapse Prevention

Some participants explicitly prioritised partner involvement in psychoeducation and contact with the therapist over partner involvement in exercises and assignments. Some patients who felt this way preferred to do (certain) exercises and tasks independently because they felt that doing them together with their partner would prevent them from doing them in their own way. Conversely, other patients and partners expressed a wish for their partner to be involved in exercises, assignments and/or relapse prevention. They mentioned, amongst other things, sensory exercises, concentration exercises, meditation/relaxation exercises, doing fun things (together), physical activities, planning and organisation exercises, communication exercises and drafting a relapse prevention plan. Some of these preferences were mainly based on the idea that partner involvement should benefit the patient. One patient, who had not completed the individual eMBCT due to motivational issues, suggested that joint participation with his partner might have helped him to perform the exercises and assignments in an adequate and disciplined manner. Preferences for partner involvement in exercises and assignments were also motivated by the wish for a couples eMBCT to pay attention to partner needs. Furthermore, participants mentioned that exercises and assignments could potentially benefit both the patient and the partner in a synergetic way. Joint exercises could provide concrete tools to help couples cope with the fatigue in life and in their relationship. In this regard, several participants proposed to devise a dyadic conversation tool. Sometimes, preferences and perceptions regarding partner involvement in exercises and assignments varied between couple members.

In several interviews and focus groups, respondents had specific ideas about how perceived barriers could be incorporated into the therapeutic activities of a couples eMBCT. For example, in relation to large differences between partners in terms of skills and preferences, one patient suggested that it might be valuable to clarify and compare these differences in the couples eMBCT. Some barriers, especially those related to lack of time and differences between partners in their skills, abilities, experiences and preferences, could only be partially overcome by involving the partner.

5. Conclusion Study 1

The findings of study 1 support the potential acceptability of a couples eMBCT for CCRF. Both patients and partners expressed a need to participate in such a couples eMBCT. Patients and their partners perceived several potential benefits, including the opportunity to empower partners to support the patient (e.g., to better understand the impact of CCRF on the patient, their role as a partner and how to provide support), to support partners with CCRF-related problems (e.g., to receive understanding for the impact of CCRF on their well-being) and to enhance the intimate relationship between patient and partner (e.g., to break or prevent the negative downward spiral of fatigue causing problems in the relationship and to improve communication). At the same time, participants identified a number of barriers. In particular, some patients and partners assumed that their partner would not be interested in being involved in therapy. For example, patients thought that their partner would not have time or should not be burdened with a couples therapy. Partners, on the other hand, felt hesitant to ask for or accept support for themselves. Although patients and partners discerned benefits for the relationship, they also expressed some concern that a couples therapy would cause tension in the relationship.

Some participants wanted the partner to be involved in therapy only in terms of psychoeducation and contact with the therapist, while others wanted the partner to also engage in intake and screening, exercises, assignments and/or relapse prevention. This suggests that a couples eMBCT for CCRF should be flexible in terms of when, how and with what intensity to involve the partner, so that the couple can decide whether or not the partner has contact with the therapist and is involved in exercises and assignments.

The strength of a qualitative study is that it provides insight into the diversity of experiences and perceptions. As we are also interested in the prevalence of these experiences and perceived benefits and barriers, and the preferences for partner involvement in CCRF therapy in a larger group of patients and partners, a subsequent quantitative study was conducted using an exploratory sequential mixed methods design [25].

6. Aims Study 2

The aim of study 2 was to validate and quantify the findings of study 1 regarding (1) the perceived needs, benefits and barriers and (2) the preferences with respect to the involvement of the partner in a couples therapy for CCRF.

7. Method Study 2

7.1. Study Design

We administered an online survey for patients with CCRF and partners of patients with CCRF. In this study, we referred more generally to a couples therapy (rather than specifically to a couples eMBCT) because not all participants in the online survey might be familiar with the concept of eMBCT.

7.2. Participants

A convenience sample of patients and partners was recruited via several channels, including (social) media, the panel of https://www.kanker.nl (i.e., the Dutch central online platform with information about cancer), patient and informal care associations, psychosocial care centres for people affected by cancer and the client newsletter of the HDI. Potential participants were directed to the HDI website (https://hdi.nl/onderzoek/companion/), which provided information about the study and the link to the anonymous survey. Patients were eligible for participation if they (had) experienced CCRF, were in a relationship and they as well as their partner were aged 18 years or older. Partners of patients were eligible to participate if they were aged 18 years or older, reported that their partner with cancer was aged 18 years or older and reported that the patient (had) experienced CCRF. As this was not a dyadic study, patients and partners could participate without the other couple member. After providing online consent, participants received screening questions. Those who did not fulfil an eligibility criterion were thanked and screened out.

7.3. Procedure and Measures

Survey questions were self-developed based on preliminary results of the focus groups and interviews [25]. A concept of the survey was pretested and refined using feedback from two patients and two partners who had participated in a focus group or an interview in study 1. The following data were collected via a secure online survey platform between March 2021 and February 2022.

7.3.1. Demographics and Clinical Background Variables

Age, sex, level of education, occupation and relationship status and duration were assessed at the beginning of the survey. In addition, participants were asked whether they themselves or their partner had been diagnosed with cancer. If both members of a couple had cancer, the participants were encouraged to choose their role in responding to the survey (i.e., patient or partner) as they thought appropriate, depending on which of them experienced more fatigue. Patients reported about their cancer and partners about the cancer of their partner (i.e., the patient). Variables included cancer type, time since diagnosis, treatment status (ongoing or time since completion), prognosis and presence of metastases.

7.3.2. Fatigue

Onset, duration and, if applicable, recovery of the patient’s fatigue were reported. Patients, but not partners, also filled in the eight-item subscale fatigue severity of the Checklist Individual Strength (CIS-fatigue). A score of ≥ 35 indicates severe fatigue [26].

7.3.3. Previous CCRF Care Use

Participants were asked whether the patient had previously used care for CCRF and, if so, what type of care. Answer categories were: physiotherapy, occupational therapy, lifestyle advice, psychological support, self-management and other (to be specified). Multiple answers could be selected. If patients had previously received CCRF care, participants were asked to report whether and how the partners had been involved in this care and how satisfied they were with the level of involvement.

7.3.4. General Need for Partner Involvement in CCRF Therapy

Participants (i.e., patients and partners of patients) were asked to answer the item ‘Do you feel a need for a CCRF therapy involving your partner/you?’ on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from (1) ‘No, no need at all’ to (7) ‘Yes, a great need.’ Patients who had previously received CCRF care were encouraged to answer the question thinking about their fatigue prior to receiving this care.

7.3.5. Perceived Benefits of Participating in a Couples Therapy for CCRF

Participants received nine (patients) or eight (partners) propositions that were answered on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from (1) ‘Totally disagree’ to (7) ‘Totally agree.’

7.3.6. Perceived Barriers to Participating in a Couples Therapy for CCRF

Participants were given 11 (patients) or 13 (partners) propositions that had to be answered on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from (1) ‘Totally disagree’ to (7) ‘Totally agree.’

7.3.7. Preferred Activities in a Couples Therapy for CCRF

Participants were presented with six (patients) or seven (partners) activities and asked to rate whether they would want them to be offered in a couples therapy. Answer categories were ‘Yes’ (preference), ‘A bit’ (some preference) and ‘No’ (no preference).

7.4. Data Analysis

Survey data were analysed descriptively, separately for patients and partners. Answers on items about needs, benefits and barriers (research aim 1) were categorised into ‘No need’/‘No perceived benefits’/‘No perceived barriers’ (answer categories 1–3), ‘Neutral’ (answer category 4) and ‘Need’/‘Perceived benefits’/‘Perceived barriers’ (answer categories 5–7). Answers to the question about preferences for partner involvement in couples therapy (research aim 2) were categorised as ‘Preference’ (answer category 1), ‘Some preference’ (answer category 2) and ‘No preference’ (answer category 3). Means and SDs or frequencies and percentages are reported, as appropriate. Differences between participants who were eligible and dropped out versus study completers on duration of fatigue, prior CCRF care and relationship satisfaction were assessed using a t-test (continuous variables) or a Chi-square test (categorical variables). By assessing potential differences, we aim to be able to say something about the generalisability of our survey results.

8. Results Study 2

8.1. Sample

A total of 418 participants provided consent. Of these participants, 46 were screened out due to ineligibility and 34 dropped out before starting the survey. Of the 262 eligible patients and 76 eligible partners that were included, 172 (65.6%) patients and 55 (72.4%) partners completed the survey. Patients were on average 54 years of age (range: 26–79 years) and mostly female (74.4%). Partners were on average 56 years of age (range: 29–78 years) and also mostly female (67.3%). Three quarters of the patients (75.0%) had a CIS-fatigue score indicating severe fatigue. A total of 117 (68.4%) patients and 30 (54.5%) partners reported previous use of CCRF care. Of the patients reporting to have used CCRF care before, the majority (71.0%) reported that their partner had been involved in this care to some degree, and that this partner involvement had varied from providing encouragement, taking over chores so that the patient could spend time on the therapy and talking with the patient about the content of the therapy. Of the 30 partners reporting that the patient had previously used CCRF care, 28 (93.3%) reported to have been involved in this CCRF care. For more details about the sample characteristics of study 2, see Table 3.

| Characteristic | Patients N = 172 n (%)a |

Partners N = 55 n (%)a |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age, in years, M (SD), range |

|

|

| Sex, female | 128 (74.4) | 37 (67.3) |

| Relationship status, married and cohabitating | 129 (75.0) | 42 (76.4) |

| Relationship duration | ||

| Up to 10 years | 25 (14.5) | 8 (14.5) |

| 10 years and more | 147 (85.5) | 47 (85.5) |

| Level of education | ||

| Low | 73 (42.4) | 19 (34.5) |

| Medium | 74 (43.0) | 23 (41.8) |

| High | 25 (14.5) | 13 (23.6) |

| Occupation | ||

| Working | 69 (40.1) | 30 (54.5) |

| Retired | 22 (12.8) | 12 (21.8) |

| Unable to work | 41 (23.8) | 1 (1.8) |

| Other | 40 (23.4) | 12 (21.9) |

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| Cancer typeb | ||

| Breast | 76 (44.2) | 9 (16.4) |

| Prostate | 14 (8.1) | 6 (10.9) |

| Leukaemia | 17 (9.9) | 3 (5.5) |

| Other | 79 (45.9) | 41 (74.6) |

| Time since diagnosis | ||

| Up to 5 years | 99 (57.6) | 36 (65.5) |

| 5 years and more | 73 (42.4) | 19 (34.5) |

| Treatment status | ||

| Not completed | 54 (31.4) | 19 (34.5) |

| Completed up to 12 months ago | 24 (14.0) | 15 (27.2) |

| Completed more than 12 months ago | 94 (54.7) | 20 (36.4) |

| I do not know | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8) |

| Prognosis | ||

| Cancer is/can be cured | 115 (66.9) | 23 (41.8) |

| Curation is not possible | 32 (18.6) | 21 (38.2) |

| Uncertain | 16 (9.3) | 9 (16.4) |

| I do not know | 9 (5.2) | 2 (3.6) |

| Metastases | ||

| Yes | 44 (25.6) | 19 (34.5) |

| No | 117 (68.0) | 35 (63.6) |

| I do not know | 11 (6.4) | 1 (1.8) |

| Fatigue characteristics | ||

| Fatigue complaints | ||

| Currently | 145 (84.3) | 52 (94.5) |

| Prior | 27 (15.7) | 3 (5.5) |

| Fatigue severityc | ||

| Severe | 129 (75.0) | n.a. |

| Nonsevere | 43 (25.0) | n.a. |

| Prior use of care for fatigue | ||

| Yesd | 117 (68.4) | 30 (54.5) |

| Psychological support | 73 (62.4) | 18 (60.0) |

| Physiotherapy | 81 (69.2) | 23 (76.7) |

| No | 54 (31.6) | 25 (45.5) |

| Partner involvement among those who reported prior use of CCRF caree | ||

| Was the partner involved? | ||

| Missing | 10 | — |

| Yes | 76 (71.0) | 28 (93.3) |

| My partner encouraged me/I encouraged my partner to start or continue with the therapy | 50 (65.8) | 20 (71.4) |

| My partner/I took over (household) chores so I/my partner had time for the therapy | 41 (53.9) | 12 (42.9) |

| My partner and I talked about the content of the therapy | 40 (52.6) | 12 (42.9) |

| My partner helped me/I helped my partner to put into practice what I/my partner had learned | 32 (42.1) | 7 (25.0) |

| My partner reminded me/I reminded my partner to do the exercises or to go to the practitioner’s appointments | 18 (23.7) | 9 (32.1) |

| My partner and I did exercises together | 10 (13.2) | 2 (7.1) |

| Otherwise | 2 (2.6) | 3 (10.7) |

| No, n (%) | 31 (29.0) | 2 (7.1) |

| Degree of involvement, mean (SD), rangef |

|

|

| Satisfied with degree of involvement | 60 (78.9) | 16 (53.6) |

- Note: Table reflects descriptive statistics of participants who completed the survey (i.e., who did not drop-out and were not screened out). For cancer and fatigue-related characteristics, partners reported about their partner, that is, the patient with cancer and CCRF. As this is no dyadic data collection, only a few couples completed the survey. Due to anonymous data collection, the partners cannot be linked to each other.

- aUnless indicated differently.

- bThe counts do not add up to the total sample size, and the percentages do not add up to 100%, because in some cases, multiple cancers were reported.

- cCIS-fatigue ≥ 35 indicating severe fatigue; CIS-fatigue = fatigue severity subscale of the Checklist Individual Strength [26].

- dAnswer categories: physiotherapy, occupational therapy, lifestyle advice, psychological support, self-management, and other (to be specified). Only the most common responses (i.e., psychological therapy and physiotherapy) are reported here. The counts do not add up to the total sample size, and the percentages do not add up to 100% as multiple answers could be selected.

- e117 Patients and 30 partners reported that the patient had previously used CCRF care. The percentages of partner involvement listed in the columns below are based on these denominator numbers.

- fScores ranging from 1 (indicating no involvement) to 7 (indicating a lot of involvement).

Patients who completed the survey were less often fatigued for < 3 months and more often fatigued for > 2 years than patients who dropped out of the survey (χ2 (4, N = 220) = 15.21, p = 0.004). Surveyed patients more often received prior CCRF care than patients who dropped out (χ2 (1, N = 253) = 6.09, p = 0.014). Partners who completed the survey reported a somewhat lower relationship satisfaction (mean = 5.15 (SD = 1.2) versus 5.57 (SD = 0.5), d = 0.42) than eligible partners who dropped out (t (72.55) = −2.22, p = 0.029).

8.1.1. Research Aim 1: Perceived Needs, Benefits and Barriers of Patients With CCRF and Their Partners With Respect to Participation in a Couples Therapy for CCRF

Patients appeared to be fairly divided about their need for a dyadic CCRF therapy, with roughly equal numbers of those who did (39.0%) and did not (43.6%) report this need. The remaining patients (17.4%) were neutral about their need for a couples therapy. Almost all partners (91.0%) reported a need for a couples therapy for CCRF.

8.1.1.1. Perceived Benefits of Participating in a Couples Therapy for CCRF

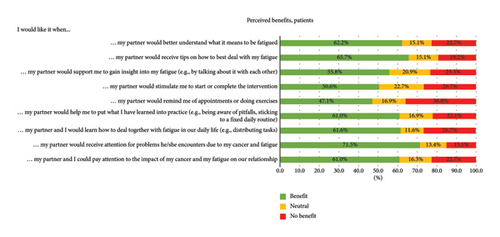

The perceived benefits reported by the largest proportion of patients were that in a couples therapy, their partner could receive attention for the problems he/she encounters due to the patient’s cancer and fatigue (71.5%) and that he/she could receive tips on how to deal with the patient’s fatigue (65.7%). The corresponding two items were also endorsed by large groups of partners (85.5% and 89.1%, respectively). A large proportion of partners (85.5%) also endorsed the item ‘I would like it when I could support my partner to gain insight into their fatigue (e.g., by talking about it with each other).’ More results are presented in Figure 1.

8.1.1.2. Perceived Barriers to Participating in a Couples Therapy for CCRF

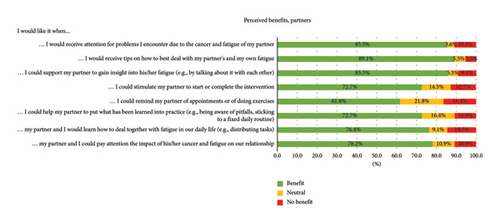

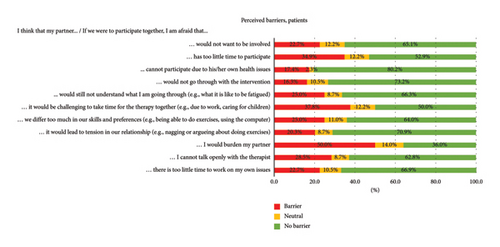

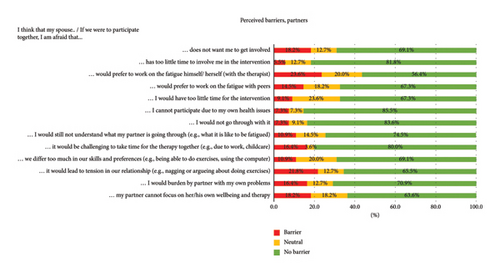

Half of the patients (50.0%) reported to be worried to burden their partner if this partner was to be involved in a dyadic CCRF therapy. Other barriers that patients commonly endorsed were that it would be challenging for the couple members to schedule time for the therapy together (37.8%) and that the partner would have too little time to participate in a couples therapy (34.9%). Among partners, the most frequently acknowledged barrier was that patients might prefer working on the fatigue on their own (23.6%). About one-fifth of both the patients and the partners (20.3% and 21.8%, respectively) indicated to be concerned that a dyadic therapy might lead to tension in the relationship. Details on perceived barriers are shown in Figure 2.

8.1.2. Research Aim 2: Preferences for Involving Partners in a Couples Therapy for CCRF

8.1.2.1. Preferred Activities in a Couples Therapy for CCRF

Large groups of patients indicated a preference for (1) receiving information and education on cancer-related fatigue in a couples therapy for CCRF (preference: 58.2%, some preference: 29.1%), (2) receiving feedback from the therapist on their progress (preference: 64.5%, some preference: 23.3%) and (3) doing exercises (preference: 68.0%, some preference: 18.0%). The preferences for couples therapy activities that were most frequently reported by partners were: (1) receiving information and education on cancer-related fatigue (preference: 58.2%, some preference: 29.1%), (2) contact with the therapist to talk about cancer-related fatigue and its effects (preference: 49.1%, some preference: 27.3%) and (3) performing exercises (preference: 54.5%, some preference: 18.2%). Keeping an online diary was the least endorsed item among both patients (no preference: 43.0%) and partners (no preference: 49.1%). Further details of the preferred activities for a dyadic CCRF therapy can be found in Supporting file 4 (Figure 1).

9. Conclusion Study 2 and Integration of Findings

The results of the online survey were largely consistent with the qualitative findings from the focus groups and interviews (study 1). In both studies, patients as well as partners expressed a need for a couples therapy for CCRF. They thought it could benefit (1) the patient, (2) the partner and (3) the relationship (i.e., the patient and partner as a couple). The need for a couples therapy for CCRF seemed to be stronger and more common among the patients in the focus groups and interviews (study 1) than among the patients in the online survey (study 2). This difference may be explained by the fact that unlike the surveyed patients, all interviewed patients had previous experience with CCRF therapy and therefore may have had a more positive attitude towards it. In addition, the concept of a couples’ version of CCRF therapy may have been more tangible to them. We found evidence to support this explanation in a post-hoc explorative analysis of our survey results (study 2), which indicated that patients who had previously received CCRF care more often indicated a need for a couple’s intervention than those who had not. We also explored whether patients who were still experiencing severe fatigue were more likely to report a need for couples therapy than patients whose fatigue had improved but found no statistically significant difference between these groups. To conclude, the findings of study 2 are important in demonstrating that, also in a larger sample, considerable groups of patients and partners are positive about the idea of a couples therapy for CCRF.

In line with study 1, the quantitative findings of study 2 indicated that partner involvement in CCRF therapy was considered desirable for most activities that are currently included in the individual eMBCT (e.g., psychoeducation, contact with the therapist, exercises, assignments and relapse prevention). However, as in study 1, individual preferences varied widely. Moreover, patients and partners identified several barriers and reservations that might prevent them from participating in a couples eMBCT. For instance, half of the patients surveyed said they were afraid of burdening the partner with a couples therapy. Patients in the focus groups and interviews voiced similar concerns. Yet, this fear appeared to be unfounded, as most partners in our studies endorsed the opportunity to participate in a couples therapy (i.e., over 90% of the partners in the online survey expressed a clear need for a couples therapy). Furthermore, while almost 35% of the patients in the online survey thought that their partner would have too little time to attend therapy, less than 10% of the participating partners reported that this was actually the case. Within-couple comparisons in the focus group and interview study confirmed that perceived barriers were sometimes based on mutual misunderstandings between couple members. Another important barrier to consider, mentioned by both patients and partners in both studies, is the fear that couples therapy for CCRF might increase tension in the relationship and/or lead to confusion about the roles and responsibilities of the patient and the partner during the therapy. The explanations given in the qualitative study suggest that this frequently mentioned barrier (patients: 20.3%, partners: 21.8%) may, paradoxically, in some cases reflect a need at the same time: for example, behind the concern or fear that participation in couples eMBCT would lead to issues with regard to patient and partner roles and responsibilities, there may be a desire to rebalance roles and responsibilities between partners. And, the fear that participation in couples eMBCT would lead to tension in the relationship may also reflect a wish to openly discuss relationship issues in dealing with the fatigue, including mutual feelings of guilt. In several interviews and focus groups, participants came up with specific ideas about how certain barriers could be addressed and perhaps even used in couple eMBCT.

10. Discussion

Using a mixed methods design, we conducted two studies that together aimed to provide more insight into the needs, benefits, barriers and preferences regarding a couples therapy for CCRF. Overall, our qualitative and quantitative results support the potential acceptability of a couples therapy for people with CCRF and their partners. More specifically, both patients and partners indicated that involving the partner in therapy would be desirable and that they expected benefits from participating in such a couples therapy. Yet, they clearly suggested that there should be flexibility in terms of when, how and with what intensity to involve the partner. Based on divergent preferences, we determined that a couples therapy must provide flexibility regarding the degree, intensity and type of partner involvement. Dyadic psychoeducation can be used as a solid starting point to manage expectations and reduce perceived barriers.

There is a large and growing body of literature that suggests that dyadic therapies may benefit the adaptation of couples confronted with cancer [8, 10, 27–34] although to date there are few dyadic therapies that primarily target (chronic) cancer-related fatigue. Our findings are consistent with a pilot study that supported the acceptability of dyadic acceptance and commitment therapy and suggested that this would be promising in reducing fatigue in patients with advanced gastrointestinal cancer and burden in their family caregivers [34]. Furthermore, the finding that patients do not always have the words to describe their CCRF experiences, which makes it difficult for them to communicate with their partner, corroborates the findings of a previous qualitative study [35]. This supports their need for the therapist to involve their partner.

A strength of this study is the mixed methods approach, with a quantitative survey largely confirming the results from the qualitative interviews and focus groups. Limitations are that we used a convenience sample for our survey and that it was hard to reach partners. The fact that almost all partners surveyed were interested in a couples therapy seems to indicate that the partners who responded were particularly interested in the topic (i.e., self-selection bias). We found that partners who completed the survey had a somewhat lower relationship satisfaction than those who dropped out, so our findings may be less generalisable to partners with a high relationship satisfaction than to partners with a lower relationship satisfaction. Patients who completed our survey were often fatigued for a longer period (> 2 years) than patients who dropped out. Furthermore, completers more often received prior CCRF care. Thus, our findings apply to patients who are most affected by long-term fatigue. Therefore, our results may not be generalisable to the entire target population of patients with cancer and their partners, but they seem to hold for the group that is probably most likely to seek help: the most affected patients and the partners with lower relationship satisfaction. We found that a relatively small proportion of patients in the survey expressed an interest in a couples therapy for CCRF. While our data do not provide conclusive evidence on the possible reasons for this, we recognise that a couples therapy may not be suitable for all patients and partners. Therefore, couples eMBCT should not replace but rather remain an alternative to individual eMBCT. Healthcare providers should discuss with each patient their therapy needs and preferences and, if the patient has a partner, the potential advantages and disadvantages of couples therapy. In these discussions, perceived barriers to couples therapy could be explored and clarified, in order to facilitate an informed decision about the most appropriate therapy.

10.1. Clinical Implications

Based on the current findings, we adapted the evidence-based individual patient-centred eMBCT into a couples eMBCT, named COMPANION [36]. Adaptations compared to the patient-centred version mainly concerned: three additional video call consultations between patient, partner and therapist; psychoeducation for the partner; additional exercises for patient and partner (to be performed together or independently); and an extra session focused on the couple’s mutual relationship and mindful communication about fatigue. Together with their therapist, couples can decide on how and to what extent the partner will be involved. Dyadic psychoeducation is used as a solid starting point to manage expectations and reduce perceived barriers. While the need for a flexible approach to partner involvement was evident, too much flexibility poses the risk of negating the benefits of a truly dyadic approach and focussing too much on the partner and their own issues. We look forward to learning how participants experience and deal with this flexibility. In a current pilot study, we are investigating the acceptability and potential effectiveness of the COMPANION eMBCT in reducing fatigue in patients, as well as its feasibility and potential working mechanisms [36]. Future therapies and research could consider whether and how to involve relatives in the CCRF therapy for patients who do not have a partner, as a dyadic approach may also be beneficial for these patients and their relatives.

Disclosure

Parts of the results of this study have been presented at the conference of the International Psycho-Oncology Society (IPOS) in Toronto, 2022: https://journals.lww.com/jporp/Documents/2022%2520IPOS%2520Congress%2520Abstracts.pdf.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

S.I.v.D., F.M., R.A.M.v.W., M.H. and M.L.v.d.L. made substantial contributions to the concept and design of study. S.I.v.D. and R.A.M.v.W. recruited participants for the interviews and focus groups, getting help from the secretariat and the therapists of the Helen Dowling Institute. F.M. recruited participants for the online survey, with assistance from all the other authors.

S.I.v.D. and W.S. conducted the interviews and focus groups. S.I.v.D. and F.M. developed the survey questions together with the other authors. S.I.v.D., R.A.M.v.W. and F.M. analysed and interpreted the qualitative and quantitative data. All other authors actively contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data. M.H. and M.L.v.d.L. provided academic scientific direction for the study (design, analysis and reporting). S.I.v.D. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All the other authors critically revised the manuscript. All authors have sufficiently participated in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content and approve the final version of the manuscript to be published.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF Kankerbestrijding, 12794). FM receives funding from NKCV Foundation (Nederlands Kenniscentrum Chronische Vermoeidheid).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participants for sharing their experiences and preferences with us. We thank Wike Seekles (WS) for her help in guiding the focus groups and conducting the interviews. We thank the secretariat and therapists of the Helen Dowling Institute for their assistance in the recruitment of participants for the interviews and focus groups.

Supporting Information

Supporting File 1: Guides for Interviews and Focus Groups with Persons Who Had Followed the Individual eMBCT for CCRF and Partners of These Persons. Supporting file 1 contains two semistructured interview guides that were developed to lead the conversations in qualitative study 1, that is, one for patients and one for partners.

Supporting File 2: Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) Checklist (Study 1). Supporting file 2 includes the completed Reporting Standards for Qualitative Research (RSQR) [21] guidelines for reporting study 1.

Supporting File 3: STROBE Statement—Checklist of Items that Should Be Included in Reports of Observational Studies (Studies 1 and 2). Supporting file 3 lists the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines [22, 23], which we completed in relation to our report of both study 1 and study 2.

Supporting File 4: Preferences for Involving Partners in a Couples eMBCT for CCRF (Online Survey among (a) patients (n = 172) and (b) partners (n = 55)). Supporting file 4 presents a figure of our online survey findings (study 2) with regard to the preferred activities for a dyadic CCRF therapy among (a) patients and (b) partners.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.