Exploring Motivation for Engaging in Exercise During the First Six Months of Childhood Cancer Treatment: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

Purpose: To improve the understanding of what influences the motivation of children and adolescents diagnosed with cancer to engage in exercise during the first six months of treatment.

Materials and Methods: Qualitative design using semistructured interviews with children (6–17 years) diagnosed with cancer (n = 12) and their parents (n = 12). A deductive thematic analysis based on self-determination theory was applied.

Results: Three predefined themes described different aspects of motivation for exercise during treatment.

Amotivation: Treatment-related illness and fatigue causing amotivation was described as a dominant barrier. Exercise driven by negative reinforcements facilitated short-term exercise engagement but was perceived as amotivation.

Controlled Regulation: Exercise regulated by exercise professionals could facilitate and introject positive experiences with exercise (i.e., ameliorated side effects) and create confidence in physical capabilities.

Autonomous Self-Regulation: An autonomy-supportive approach using cocreation and age-appropriate and treatment-regulated exercise, facilitated trust, and confidentiality with exercise professionals.

Conclusion: Motivation for exercise is a dynamic interplay that can be facilitated or negatively affected by treatment, parents, peers, and external regulation. Exercise interventions should use an individual and autonomy-supportive approach, encompassing treatment-related daily variations of physical capacity. Externally regulated motivation can facilitate exercise on a short-term basis when children are inactive or hesitant to engage in exercise.

1. Introduction

Early initiation of physical exercise limits the physical deterioration caused by inactivity and treatment-induced toxicities, such as muscle wasting, altered body composition, balance deficiencies, and impaired gait during cancer treatment in children with cancer [1]. Motivation plays a crucial role in child engagement in exercise throughout the cancer treatment trajectory [2].

Cancer treatment is challenging for children; the physical and emotional toll of cancer and treatment (primarily chemotherapy, radiation, and steroids) severely impacts physical capacities (i.e., muscle strength, endurance, and physical competence) within weeks after treatment initiation alongside fluctuating periods of fatigue and lethargy throughout the treatment trajectory [1, 3–5]. Further, being hospitalized for long periods also causes social isolation, separating children from their peers. The psychosocial consequences include the loss of autonomy and reduced quality of life [6–8]. Supervised physical activity and exercise can counteract these adverse physical and social side effects of childhood cancer treatment across diagnoses, as shown in controlled trials [8–11]. However, the body of evidence shows that adherence rates to exercise interventions have substantial individual variability [8–11]. Motivation is a driver for adhering to and engaging in physical activity and exercise, and it might be a crucial variable for understanding how participating and engaging in exercise fluctuate throughout cancer treatment [12–14]. It is, therefore, relevant to explore the barriers and facilitators of motivation in children and adolescents during cancer treatment, as this influences their ability to potentially mitigate treatment-related side effects.

This study aims to improve our understanding of what influences the motivation of children and adolescents diagnosed with cancer (ages 6–17) to engage in an exercise intervention during the first 6 months of cancer treatment. In this study, motivation will be operationalized by the following three areas: amotivation, controlled regulation, and autonomous self-regulation.

2. Methods

2.1. Approach

This study used a qualitative design based on in-depth semi-structured interviews [15]. Data were analyzed using a deductive thematic analysis based on the principles of self-determination theory (SDT) [16–18]. The reporting of the study follows the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research in Medical Education (SRQR) [19].

2.2. Context

The participants in this study were all enrolled and allocated to the intervention group in the Integrative Neuromuscular Training in Adolescents and Children Treated for Cancer (INTERACT) randomized controlled trial [20]. The INTERACT trial investigates the effects of a 6-month integrative neuromuscular training intervention in children and adolescents diagnosed with cancer (age 6–17 years) from three of four university hospitals in Denmark (Aarhus, Odense, and Copenhagen University Hospital—Rigshospitalet) compared with an active usual care group.

2.3. Intervention Components

In addition to usual care, the intervention group received a 6-month strength-based exercise intervention: integrative neuromuscular training. The exercise intervention started within 2 weeks of treatment initiation and was designed as games and play-based exercise or performed as a structured strength-and-conditioning program, depending on the participant’s age, gross motor skill level, and daily variations in side effects (e.g., nausea, fatigue, dizziness, pain). In contrast to more traditional forms of physical activity (e.g., walking, cycling), integrative neuromuscular training specifically targets neuromuscular deficits by stimulating neural plasticity, enhancing motor unit recruitment, firing frequency, and synchronization of motor unit activation [21–26]. This integrative neuromuscular training program is designed to improve physical fitness in children aged 6–17 during cancer treatment.

The intervention used an autonomy-supported approach; although exercise professionals designed and supervised the exercise sessions, the individual participant’s decisions, perspectives, and interests were acknowledged and included. Consequently, the participant was encouraged to suggest exercises or activities in each session.

The children would receive supervised training when hospitalized or visiting the outpatient clinic. When at home, the participants were encouraged to do home-based exercises based on an individual program, or they could choose to do any type of physical activity (any bodily movement that would increase their heart rate), depending on the child’s physical state. Elaborative descriptions of the components of the intervention are described elsewhere [20].

2.4. Sampling Strategy

A purposeful criterion-based sampling strategy was used [27, 28]. Participants and parents were interviewed between February 2022 and March 2023. Eligible for this study were children (participants) who were enrolled in the INTERACT intervention arm for at least 3 months (and their respective parents or guardians) from all three centers and who were no more than 2 months post-intervention termination.

We strived to select children and adolescents with different diagnoses, ages, sexes, and adherence rates to the exercise intervention.

2.5. Data Collection Methods and Instruments

An overall framework for the interview guides used in this study was specifically developed to collect insights from the participants and their parents concerning their experience with the intervention based on the principles of SDT: (1) autonomy (e.g., “Can you give an example of a physical activity decided during the sessions?” and “Did you do some of the components of the intervention on your own?”); (2) relatedness (e.g., “Are you good at motivating yourself to engage in physical activity, or do your parents/siblings/friends help motivate you? If so, how?”); and (3) competence (e.g., “Do you feel any change in your physical condition due to the intervention?”).

Three semistructured interview guides were developed: one for children (aged 6–10), one for adolescents (11–18), and one for parents (Supporting file 1). We divided the participants into two groups to accommodate potential differences in developed language and knowledge. For example, the interview guide for younger children would accommodate how young participants would not understand terms like exercise and physical activity (would be translated to “movement that makes you sweat”) or would have prompting questions to help them distinguish side effects.

Parents’ questions were framed as proxies, and they were also asked to recollect how they viewed their own role during exercise and physical activity at the hospital and at home.

Participants and parents were interviewed separately, but the parents were present if requested by the child.

Both interviewers (NNB and PSA) had extensive experience with communicating with children diagnosed with cancer and their parents in the context of physical activity. None of the interviewers and participants had met previously. As one of the two interviewers (PSA) conducted the intervention in one center, interviewer (NNB) conducted these interviews. Interviews were scheduled with the parents and took place in a quiet, undisturbed environment (the patient’s room or a hospital conference room), and they were audio-recorded. Online, videoconference-based interviews were used and recorded if an interview at the hospital was impossible.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

The present study complies with the Helsinki II Declaration, and the handling of data has been approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (jr. nr.: P-2021-14). Furthermore, the INTERACT study has been approved by the Danish National Committee on Health Research Ethics (Approval Number: H-20040897).

For the interviews, the participants all provided informed consent to participate and, independent of age, were asked if they would like their parents to be present during the interview.

2.7. Data Processing

In this study, the participants’ motivation, including facilitators and barriers to participation in physical exercise and physical activity during cancer treatment, is based on the principles of SDT and how they can be applied in the healthcare context [12, 14, 18]. SDT illuminates the dynamic interplay between intrinsic and extrinsic motivational forces (16–19): two distinct forms of motivation that drive human behavior. Intrinsic motivation arises within the individual, stemming from internal desires, interests, and personal satisfaction. The driving force behind intrinsic motivation is often the inherent pleasure, curiosity, or sense of accomplishment one experiences while engaging in the task itself. Conversely, extrinsic motivation originates from external factors and relies on external incentives, money, praise, social status, or even punishment, to encourage behavior.

The theory identifies three inherent intrinsic psychological needs: autonomy (“the feeling of being the origin of one’s own behavior”), competence (“feeling effective”), and relatedness (“feeling understood and cared for by others”) as a counterpart to extrinsic motivation, which shapes this interplay [12].

As a continuum, SDT spans from pure autonomy-driven or -supported motivation to strictly externally controlled behavior deprived of any autonomy, leading to amotivation. This continuum, and how intrinsic (autonomy, relatedness, and competence) and extrinsic motivational factors are regulated into behavior, is addressed in this study as amotivation, controlled regulation, and autonomous self-regulation, as these domains broadly cover the whole continuum [12, 18]. This applied analytic approach favors internalization (i.e., how a regulated behavior can potentially develop a framework for sustained autonomous behavior).

2.8. Data Analysis

Participant and parent interviews were transcribed ad verbatim, separately, and PSA and NNB thematically analyzed the transcripts using a deductive approach, as described by Braun and Clarke [16].

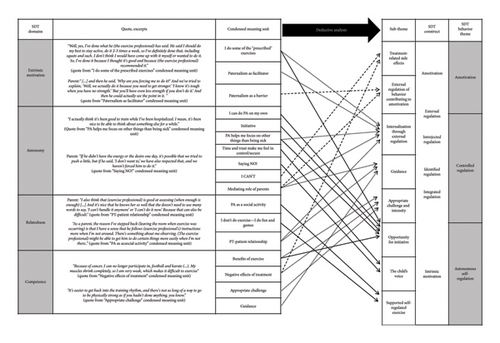

The analysis consisted of five steps: (1) an overall framework for potential codes was written while listening through the recorded interviews; (2) coding the transcripts into meaning units, which would be categorized within the overall self-determination domains: autonomy, relatedness, competence, and extrinsic motivation; (3) transforming the meaning units into condensed units; (4) further categorizing the units within the three self-determination behavior regulation domains (amotivation, controlled regulation, autonomous self-regulation) and comparing the themes with the transcribed data to ensure accurate representation; and (5) the meaning units and categorization were iteratively discussed within the author group, and the themes were refined according to the discussion. See Figure 1 for a visual representation of the analysis, including identified themes and subthemes.

2.9. Techniques to Enhance Trustworthiness

In this study, trustworthiness is based on concepts of credibility, dependability, and transferability [29]. Measures taken to improve credibility and transferability are described in the sampling strategy, data collection methods, and analysis.

We continuously interviewed and analyzed data to assess the potential saturation of data if no new themes emerged. We were aware that interviewing and analyzing data simultaneously may have affected dependability, as the interviewers may have narrowed their focus. However, we did not alter the interview guide. Furthermore, the deductive approach dictates maintaining the scope of the study.

3. Findings

The data comprised 24 interviews with 12 participants paired with their parents. Ten interviews were conducted as online video consultations, and two interviews were conducted via telephone. We included nine boys and three girls with a median age of 11 (range 6–17). Six participants were diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, six with different types of solid tumors, one of whom had a solid tumor in the central nervous system (see Table 1 for a description of the participants). Three participants—one girl (aged 8 years) and two adolescents (16-year-old boy, 17-year-old girl)—who had very low adherence rates to the supervised exercise sessions were approached but declined to participate or did not respond.

| Informants’ characteristics | Children (n = 12) | Parents or guardians (n = 12) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (male/female) | 9/3 | 4/10∗ |

| Age (median, [range]) | 11 (6–17) | — |

| Combined∗∗/separate interviews | 5/7 | 5/7 |

| Centers | ||

| Copenhagen University Hospital | 7 | |

| Aarhus University Hospital | 3 | |

| Odense University Hospital | 2 | |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Hematologic cancers | 6 | |

| Extracranial solid tumors | 5 | |

| CNS tumors | 1 | |

| Adherence to exercise during treatment | ||

| HighA | 3 | |

| IntermediateB | 6 | |

| LowC | 3 | |

| Habitual activity level | ||

| HighD | 4 | |

| IntermediateE | 5 | |

| LowF | 3 |

- ∗Two sets of parents were interviewed together.

- ∗∗Parent and child were present during the interview.

- AHigh: participated in ≥ 80% of expected supervised exercise sessions (24 sessions).

- BIntermediate: participated in 50%–79% of expected supervised exercise sessions.

- CLow: participated in < 50% of expected supervised exercise sessions.

- DHigh: > 8 active hours outside school activity per week.

- EIntermediate: between 3 and 7 active hours outside school activity per week.

- FLow: < 2 active hours outside school activity per week.

Several factors facilitating the initiative and, ultimately, autonomous exercise or barriers leading to amotivation were identified. Based on the analysis, these are described within the three SDT behavioral domains: amotivation, controlled regulation, and autonomous self-regulation. See Figure 1 for an overview of the analysis, themes, and subthemes. An overview of identified facilitators and barriers for motivation in each theme can be found in Table 2.

| Mediating factor | Facilitator | Barrier | Described in theme | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contextual factors | Treatment | Feeling able to counteract treatment-related physical decline |

|

|

| Exercise perceived as a positive part of treatment—a welcome break from routines and procedures | Controlled regulation | |||

| Structured support for physical activity and exercise |

|

|

|

|

| Content of physical activity and exercise | Appropriate, challenging and fun activities initiated by exercise professionals | Unclear expectations | Autonomous self-regulation | |

| Clear boundaries and guidelines | Lack of structure and direction | Controlled regulation | ||

| Novelty and variety of exercise and physical activity | Monotony and predictability with minimal personal engagement and ownership | Supported-self-regulated exercise | ||

| Social support | Parents |

|

|

Controlled regulation |

| Exercise professional |

|

Using authority to hardline exercise | Controlled regulation | |

| Peers | Peers serve as realistic role models for what is possible | Peers highlight what the child cannot do or should be able to do | Autonomous self-regulation | |

- Note: Overview of identified facilitators, barriers, and explanatory factors within each theme.

- Abbreviation: PA = physical activity.

3.1. Theme: Amotivation

3.1.1. Treatment-Related Side Effects

When you’re here, it’s because you’re undergoing treatment or going through a particularly tough time. During that month when I had pneumonia, my energy was very low. And then they came in and asked, “What do you say to a little exercise? Just getting up, out of bed, standing up, sitting down, stepping once, up and down?” And I said, “No, I can’t do it anymore!” All my energy is being used to fight cancer. So right now, I really need all my energy.

(Participant, 16 years)

If I’ve been feeling really awful, then I haven’t been able to do anything […] I mean, it was like I couldn’t do anything at all.

(Participant 17 years)

Physically, I think it’s difficult to find something measurable—because [girl] has been very ill during certain periods. So, you could say there may have been a period where we thought it was working. And when we have been here many times, she has received a lot of training. And she thought she could do a lot. And then suddenly, she had a setback, and we’re back to square one. It’s hard to say whether it’s the training itself that makes it better or if it’s the side effects of the medication that are wearing off.

(Father to participant, 9 years)

Experiencing these fluctuating periods of either feeling ill and being sedentary versus active and closer to usual self was a source of frustration and amotivation for parents and participants alike.

3.1.2. External Regulation of Behavior Contributing to Amotivation

Child: I hate it [doing exercise]. I don’t like it. It’s my mother’s idea.

Mother: Every time, right? Well, it’s really serious. I say, “If you don’t come now, I’ll unplug the internet.” That’s when he goes, “Okay, okay.” And then we go.

Interviewer: But you still do it?

Child: Yes. […] Because there are consequences if I don’t.

(Mother and participant, 10 years)

It’s mostly just my dad who kind of pushes me because I don’t really enjoy exercising […] He just scolds me […] And, well, it’s not like it makes me want to exercise more. It’s just like that. Well, I do want to get stronger, but maybe that’s not the best motivation.

(Participant, 17 years)

Children would respond by further declining physical activity and exercise unless they experienced more intrinsically motivated drivers (e.g., feeling a perceived improvement of physical competencies).

3.2. Theme: Controlled Regulation

3.2.1. Internalization Through External Regulation

At home, we’ve said: “You have to do this before you continue watching your screen.” He has been a bit grumpy about it, but he has done it. And then he himself actually said at one point: “It was good that you told me to do it because I can feel that I’m getting stronger.”

(Mother to participant, 8 years)

I can actually participate in a lot more. Today, we’re even going up [the stairs] to the 13th floor. I’ve come a long way. I’ve improved a lot. And there’s a lot more I can do.

(Participant, 14 years)

[…] as a caregiver, you need to have different things that can motivate [the participant to go to the hospital]: There is pampering. There are things you can buy. And this exercise has been one of the things that we could use as motivation.

(Father to participant, 14 years)

I think it makes so much sense. I easily believe that you can fall into a mindset where, when your child gets ill, there are many hospitalizations. And, well, that’s what we experienced. Almost from one day to the next, he was lying in a hospital bed most of the time. Trying to get him up and moving early on, I believe, has been crucial for his progress, and he had a really good treatment trajectory because he was out of that bed early on and active. He almost didn’t have a chance to just lie there, because then [the exercise professional] would come, and they would do all sorts of things, play and exercise, and whatever they were up to.

(Mother to participant, 6 years)

Controlled regulation was therefore a necessary tool to ultimately introject and internalize the importance of physical activity and exercise and to facilitate motivation.

3.2.2. Guidance

It’s really fantastic [the training]. It’s great to have someone with enthusiasm and motivation that we as parents don’t possess. And having someone external who connects well with [girl] and enjoys working with her is very positive […] because it gets her going—maybe more than what we would do. We’re all caught up in our duties and “must-do” tasks. So it’s really cool to have someone come from the outside with an “excitement task” […] Dad is very into being active and thought it was a great idea. I also think it’s a really great idea, because we don’t currently have that same enthusiasm and motivation. So it’s nice to have some external help.

(Mother to participant, 7 years)

The reason I’ve stepped back [leaving the room when exercise was occurring] is that I have a sense that he follows [the exercise professional’s] instructions more when I’m not around. There’s something about me observing. [Exercise professional] might be able to get him to do certain things more easily when I’m not there.

(Mother to participant, 8 years)

Actually, he struggles with saying “No” sometimes. We’ve practiced it a lot—the ability to say “No.” That he doesn’t disappoint others, you know? When he really wants to do something, I also tell him that if he’s feeling nauseous, he should say “No.” And it’s not like he isn’t active at home.

(Mother to participant, 12 years)

I think it makes a difference that I see [girl] being able to do certain things with [exercise professional] that she may not always be able to do with me. It also gives me more courage as a mother to push a little and say, “Oh, you can squat down.” Because in the beginning, when [girl] was really unwell and kept pulling on me and falling many times, I became incredibly worried. Every time we were out, I held onto her all the time. But when you see that she can crawl around on the floor and do all sorts of things with [exercise professional], you also realize that if I relax a bit, she might relax more, too. I think it has definitely made a difference, especially at home.

(Mother to participant, 9 years)

In that sense, guidance and a good relationship with the exercise professional facilitated motivation. This relationship would also be essential to adjusting the intensity or challenge of exercise.

3.2.3. Appropriate Challenge and Intensity

I think that [exercise professional] has been quite good at doing something that [boy] found fun and varied, and a bit more playful than just boring training. And [exercise professional] has also, as far as I have experienced, been good at meeting [boy] where he was each day… I mean, where he was on the motivation scale, and also accepting that, “OK—today you’re not up for much.”

(Mother to participant, 8 years)

In the beginning, both [exercise professional] and I together assessed that [boy] was too tired and unenthusiastic and had too much of a negative attitude towards the training. And I think it has been so great that acknowledging that was an option. But gradually, it’s as if [boy] has become more and more curious and interested in it because he started feeling better and better. So I believe it has definitely made a difference in the course of the treatment.

(Mother to participant, 6 years)

In the beginning, every time [exercise professional] said, “Now squeeze a little, now jump, now throw that ball,” it was more fun at the start, but he also had more energy. Towards the very end [of treatment], he became so weak and affected by the treatment that he didn’t find it as enjoyable anymore. But overall, I think it has been good.

(Mother to participant, 10 years)

Well, there are times when, to be honest, I don’t really feel like it. But of course I’ve thought to myself, “Oh no, it sounds tough.” But then I’ve gone ahead and done it. And afterwards I’ve been really satisfied with myself for actually doing it.

(Participant 14 years)

To facilitate motivation and engagement in exercise, the exercise professionals therefore needed to tailor their approach to suit the child’s age and physical capabilities. This would foster a meaningful intervention for parents and participants, emphasizing the child’s autonomy.

3.3. Theme: Autonomous Self-Regulation

3.3.1. Opportunity for Initiative

He [the exercise professional] would say: “Today, you can try doing this activity or game, or something like that. It’s also okay if it doesn’t happen.” You shouldn’t feel like you must do it because it can ruin your motivation. There are already enough “must-do-activities” in this process, I’d say.

(Father to participant, 9 years)

Child: Yesterday, I simply made a whole program. Just to get “revenge” of [exercise professional] after he trained with me [laughs]. So, I made a program for the two of us to do together. He actually said it was really tough, so I’m really happy about that.

Interviewer: Awesome, good that you can push him a bit [laughing].

Child: Yeah, I did! Well, he also often lets me decide what we do, you know.

Interviewer: Yeah, so he might ask, “What do you feel like doing?”

Child: Yes, he does that every time. Like, how do I feel, what do I want to do. It’s also a good thing.

(Participant, 14 years)

Therefore, being attentive to the child’s current situation, making them speak their mind and providing them with a choice and options are necessary for facilitating self-determined exercise.

3.3.2. The Child’s Voice

Mother: Actually, we often say “yes” [to exercise while hospitalized].

Child: As far as I can recall, we’ve only said “No” once. I was furious.

Mother: It was a bad day.

Child: It was a really bad day.

(Mother and participant, 7 years)

Interviewer: Do you sometimes end up doing some of the exercises, even when you′re tired?

Child: I say, “I can do a little bit.”

(Participant, 6 years)

Sometimes we say “No.” For example, if I’m really tired, you know […] When I’ve just had chemotherapy, my numbers are down, and I can’t handle anything. But when my numbers are up, I can easily do it.

(Participant, 14 years)

3.3.3. Supported-Self-Regulated Exercise

Your older brother even said, “Oh man, we’re going to become really strong doing this!” But over time, their [siblings] interest in it has waned, and that might mean it’s not as fun for him anymore. […] So, I think he found it more fun in the beginning, but he’s still participating and still wants to do it.”

(Mother to participant, 6 years)

It’s definitely the hardest when it’s just me and [girl] there. I mean, when her siblings are at school and [mom] is at work, it’s tough to facilitate physical activities. It’s nice when her siblings come home from school, and we can be together. And if they want to go for a walk, or sit and play on the floor, or play tickle games, or anything else—she wants to join in. But when it’s just me and her, we get bored.

(Father to participant, 7 years)

…I don’t think exercising just for the sake of exercising motivates him. Being told, “We have to do this because we have to”, makes it even harder, especially in a hospital room—worse when we’ve been in isolation. Having to get up and walk around— just because—feels forced. But when it’s turned into different types of play, it’s different. You asked if he enjoyed it—I definitely think he did.

(mother to participant, 6 years)

4. Discussion

This study explored how the motivation of children with cancer to be physically active in an exercise intervention during the first 6 months of cancer treatment is affected and how the motivation for physical exercise and activity can be both facilitated and negatively affected by treatment, parents, peers, and exercise professionals.

Externally regulated behavior, primarily through parents, nurses, doctors, and exercise professionals, is inherently present from the beginning of hospitalization [30, 31]. Therefore, impersonal, compulsory, externally controlled behavior is expected and naturally occurring in pediatric health care [30, 31]. This study demonstrates how these opposing poles of autonomous self-regulated behavior versus externally controlled regulation do not constitute a binary explanation as either facilitating or inhibiting motivation for exercise and physical activity but should be regarded instead as a spectrum, where more externally regulated approaches can be necessary relative to the situation and level of motivation of the participants [14].

As our results illustrate, downright externally regulated behavior may lead to amotivation, but it can also introject positive experiences with exercise; i.e., children can eventually experience the benefits and joy of exercise if basic intrinsic needs such as autonomy, relatedness, and competence are facilitated. In SDT, this is known as internalization: “the active transformation of controlled regulation to a more autonomous form of self-regulation” [12]. Therefore, externally regulated behavior should not be considered a universal negative influence, causing amotivation, but more likely a necessary tool for introducing exercise and physical activity within the early stages of cancer treatment. According to SDT, external and introjected regulations are mainly unrelated to long-term adherence, and therefore, approaches to make participants identify and integrate this behavior must be further supported [14].

An autonomy-supported approach, being attentive to the child’s current situation and addressing exercise and physical activity, accordingly, can facilitate self-determined exercise. In line with the findings by Götte et al., being offered exercise is, in its entirety, facilitating [2]. This study further adds how participating in the decision-making process of regulating exercise (i.e., being able to decline, postpone, and plan exercise sessions) can further facilitate motivation. Novelty and variety were key to sustaining motivation, as exercise provided an engaging contrast to the passive nature of cancer treatment, fostering autonomy through playful and exploratory movements. However, maintaining variety was crucial, as repetitive exercises risked disengagement, particularly without professional guidance or a stimulating environment. Novelty has been recognized as a fundamental psychological need [32] and has been proposed as a fourth component of SDT, alongside autonomy, relatedness, and competence [33]. Our study reinforces this perspective, highlighting how novelty facilitates intrinsic, autonomous behavior [34].

As a healthcare authority, the exercise professional is an effective—albeit extrinsic—motivator and an important bystander to the parents to facilitate more exercise and physical activity. As stated by the consensus-based recommendations from the ActiveOncoKids Network: building a basis of trust between exercise professionals and children by actively involving children based on voluntariness is a key component for keeping children physically active throughout the treatment trajectory [34]. Based on our findings, we would argue that voluntariness may not be an accurate term when conducting physical activity and exercise intervention in children with cancer, as none of the included children described that they were performing systematic exercise and physical activity without at least some regulatory motivation from parent, peers, and/or exercise professionals. Instead of “voluntariness,” we believe that “autonomy-based approach” is a more accurate term, as a regulatory approach is necessary to a varying degree throughout cancer treatment. In line with the ActiveOncoKids and the International Pediatric Oncology Exercise Guidelines [34, 35], such regulatory approaches can be suggesting different intensities, exercises, or scheduling at different times for exercise, if the initial offer of physical exercise is declined. Our results demonstrate that exercise professionals can extrinsically push through exercise. Although effective, this should be used with a focus on internalizing physical behavior without compromising the child’s autonomy and the exercise professional’s confidentiality with the participants and parents to facilitate motivation and the potential long-term self-determined physically active behavior. In a clinical setting, we would advise aligning expectations with parents and relevant clinical staff when using a more regulatory approach.

The result of this study describes how parents can facilitate motivation for exercise by participating in and promoting exercise—but also how they can hinder physical activity and exercise by subconsciously undermining the child’s autonomy and limiting physical activity due to over-protective safety concerns. Nonetheless, parents or guardians constitute an important stakeholder. They have unique insight into their child’s signals and behavior, which can ensure the child’s safety and well-being during exercise and further promote exercise in a home setting. Grimshaw et al. [36] have described how parents regard themselves as an “underutilized resource.” We suggest that parents be included in planning and systemizing physical activity throughout the treatment trajectory, and potential barriers should be addressed (e.g., whether they should be present during exercise sessions).

In line with previous studies, we found several intrinsic motivational factors (e.g., improving physical competencies, maintaining self-reliance, coping with treatment-related side effects) that facilitate initiative and, ultimately, autonomous exercise [2, 36, 37]. Similar to findings presented by Petersen et al., we found peers to be an essential mediator for exercise, mostly positively by participating and thereby promoting the social benefits of exercise, including engagement, as a distraction and combatting loneliness [37]. However, the individual preference of the child is crucial; the current well-being of the child affects their incentives to be physically active with peers, as these children prefer to do physical activity alone when treatment-related side effects are high [38]. Our findings showed that peers could be used as a proxy for the competencies they were missing, which could be both a facilitator and a barrier. In situations where treatment-related side effects are highly present, it may, therefore, be more beneficial for the child to focus on small improvements in physical competence instead of how far they are from achieving normality. This highlights the need to include children in the planning of exercise sessions and whether peers should participate.

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

In this study, we used a deductive approach using SDT, which can be regarded as both a strength and a limitation, as we may have omitted factors pertaining to psychological well-being that this theory does not account for, such as emotional regulation, self-acceptance, and resilience [12]. However, we chose SDT because of its high heuristic value, being widely applied to the study of motivation in children [28, 38] and a healthcare setting [12]. We could have applied other motivational theories, such as stages of change [39] or behavioral change wheel, previously used in childhood cancer populations [40]. However, these theories apply an approach specifically for behavioral change, which is beyond the exploratory purpose of this study.

Novelty–variety was not included in our deductive analysis alongside autonomy, relatedness, and competence, which may be a limitation. While our findings did reflect the importance of novelty and variety, this need could have been explored more deeply, within the context of pediatric oncology exercise, had it been an integral part of our analysis.

Using semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions can be challenging for children and adolescents. With some of the younger children, the interviewer was required to facilitate a narrower approach, as younger children would sometimes give short or one-word answers, and the interviewer could end up asking close-ended questions (e.g. “Do you think it was fun?”), which risks introducing interviewer bias. If the child was uncomfortable with the interview situation, they could request that a parent be present. To make children feel more comfortable in the interview situation, facilitating longer vivid answers, we could have chosen interviewers who were known to the participants, such as the exercise intervention staff [41]. However, to minimize response bias (i.e., participants giving answers they think are “correct”), we chose an interviewer with limited knowledge of the participants [41].

We employed a purposeful, criterion-based sampling strategy to ensure diversity in age, diagnosis, and exercise adherence. We approached three children: one who withdrew from the intervention after 3 months and two with very low adherence to supervised training during hospitalization. These children either declined participation in the interviews due to lack of interest or did not respond. While this may raise concerns about the sample’s representativeness, other children with low adherence did participate and provided recurring insights into amotivation and barriers, such as a general lack of interest in physical activity and exercise throughout treatment. To further contextualize adherence within the study population, findings on acceptance, attrition, and adherence to the intervention and physical assessments have been published elsewhere [42].

4.2. Contributions to the Field

Although exercise interventions may be challenging to conduct in children during the first 6 months of cancer treatment, with fluctuating side effects and hospitalization, children can be motivated to participate. A clinical environment that reinforces physical exercise offers supervised exercise and uses an autonomy-supportive and age-appropriate approach, i.e., key for facilitating motivation and reducing sedentary behavior. For children who are sedentary or reluctant to participate in exercise, a more external regulatory approach may be useful but should be used with the intent of introjecting and ultimately internalizing behavior through autonomy support. To do so, facilitating principles such as co-creation, diverting attention from treatment-related side effects through fun activities, and social interactions should be incorporated to make children with cancer identify and integrate exercise and active behavior into their everyday lives.

Supporting autonomy does not mean that exercise and physical activity during hospitalization should be regarded as purely voluntary, as regulatory approaches are needed and can facilitate motivation. Similarly, adjusting exercise to treatment-related side effects should not compromise the intensity of exercise, as this secures the long-term effectiveness of the exercise interventions. Clinical knowledge of treatment and treatment-related procedures and close cooperation with parents, nurses, and doctors are therefore necessary to conduct meaningful and effective exercise and physical activity interventions in the fluid nature of treatment-related side effects. When oncologists and nurses actively support physical activity, they serve as key social agents who can promote adherence and help shift motivation toward more self-regulated behavior. Appropriate intensity and challenge do not necessitate exercise being regarded as exhausting or daunting but rather as an important factor to maintain and increase motivation.

5. Conclusion

Treatment-related side effects are key barriers to participation in the exercise; strategies for motivating children to be physically active during treatment are therefore crucial to counteract the adverse physical and social side effects of childhood cancer treatment across diagnoses. Externally regulated motivation (e.g., through supportive use of professional authority) is a necessary tool, as it can facilitate exercise on a short-term basis when children are sedentary and hesitant to engage in physical activity and exercise. However, more internally regulated approaches, supporting the child’s autonomy, and acknowledging concerns and the current physical state through appropriate and personalized exercise can all contribute to motivation and long-term engagement. Factors such as parents and peers can be engaged to facilitate motivation further. Being trained by a familiar exercise professional can establish secure boundaries and create a foundation for staying motivated throughout cancer treatment—even when side effects are considerable.

Disclosure

None of the funders had any role in the design of this study, in the collection of data, the analysis, the interpretation of data, or the dissemination of data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The INTERACT study has been peer-reviewed and funded by the Danish Childhood Cancer Foundation (Børnecancerfonden—Grant number: 2019-5954, 2020-6769, 2021-7409, and 2022–8142), the Research Fund of Copenhagen University Hospital, Rigshospitalet (Grant number: E-22597-01), the Capital Region of Denmark Research Foundation for Health Research 2020 (Region Hovedstaden—Grant number: A-6868), Helsefonden (Grant number: 20-B-0409), Danish Cancer Research Fund (Dansk Kræftforskningsfond—Grant number: FID2157728), the Research Fund of the Association of Danish Physiotherapists (Danske Fysioterapeuter—Grant number: R23-A640-B408), Fabrikant Einar Willumsen’s Memorial Scholarship (Fabrikant Einar Willumsens Mindelegat—Grant number: N/A), Holm and wife Elisa F. Hansen’s Memorial Scholarship (Holm og Hustru Elisa F. Hansens Mindelegat—Grant number: 21015), Danish Cancer Society (Kræftens Bekæmpelse—Grant number: R325-A19062), and Axel Muusfeldt Foundation (Axel Muusfeldt Fonden—Grant number: 2023-0056).

This work is part of the Childhood Oncology Network Targeting Research, Organization and Life expectancy (CONTROL).

Acknowledgments

A special thanks to the participants and their parents at the Department of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine at Copenhagen University Hospital-Rigshospitalet, the Department of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine at Aarhus University Hospital, and the Department of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology at H.C. Andersen Children’s Hospital, Odense University Hospital, for making this study possible. We are also grateful to medical writer Jon Jay Neufeld for providing language editing of the final manuscript.

Supporting Information

Supporting File title: Supporting File 1 Interview Guide for Children, Adolescents, and Parents. (Legend: Interview guide for children, adolescents, and parents [translated from Danish]).

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to Danish and EU personal data legislation but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.