Differences in Psychological Distress of Cancer and Hemodialysis Caregivers: A Comparative Cross-Sectional Study in Lebanon

Abstract

Background: Chronic illnesses, such as cancer and end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), impose significant emotional and physical burdens not only on patients but also on their caregivers. Caregivers play a vital role in providing care, often facing psychological distress, including anxiety and depression, while their quality of life (QoL) may deteriorate. This study aims to compare anxiety, depression, and QoL among caregivers of cancer and ESKD patients in Lebanon.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted with 134 caregivers, including 71 cancer caregivers and 63 hemodialysis caregivers, at the Hôtel Dieu de France University Hospital in Beirut. Participants completed the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and the World Health Organization QoL (WHOQoL–BREF) Scale.

Results: Caregivers of hemodialysis patients reported significantly lower QoL scores compared to cancer caregivers (p = 0.0006). Anxiety was prevalent in both groups, with no significant difference in anxiety or depression levels between the two groups. However, caregivers’ educational level (p = 0.01), anxiety scores (p = 0.006), and the patient’s comorbidity count (p = 0.007) significantly predicted QoL. Caregivers with higher education and fewer anxiety symptoms reported better QoL.

Conclusion: Caregivers of ESKD patients experience poorer QoL than cancer caregivers, though both groups suffer from high anxiety and depression. To address these disparities, we emphasize the need for universal healthcare coverage, targeted support programs, and routine caregiver well-being assessments.

1. Introduction

Chronic illnesses such as cancer and end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) not only affect patients but also significantly impact their caregivers [1]. As the main care for these diseases is given at home, the burden of caregiving falls most often on family members. These caregivers play a crucial role in managing and supporting the patients, providing both physical and emotional care [2]. Their responsibilities include administering medication, managing side effects, reporting any issues, keeping other family members informed, helping patients make treatment decisions, and transporting patients to the hospital for treatment sessions [3]. While caregiving can be a meaningful experience, it can also be overwhelming, leading to anxiety and depression, and can adversely affect the caregivers’ quality of life (QoL) [4].

Moreover, existing research extensively documents the psychological burden on caregivers of cancer patients, showing that they often experience high levels of anxiety and depression (with a reported prevalence of 46.55% and 42.30%, respectively) [3]. This distress is largely attributed to the emotional strain of supporting a loved one through a life-threatening illness [3]. Similarly, caregivers of ESKD patients face significant emotional and physical demands, often dealing with the unpredictability of the disease and the need for continuous medical care [5]. In a study, 30.2% of ESKD caregivers reported depression and 52% had anxiety [6]. Both groups of caregivers frequently experience a decline in their QoL as they struggle to manage their own well-being while providing support for the patient [3, 4]. Previous studies have shown that hemodialysis patients tend to have a worse QoL compared to cancer patients [7], and that patients’ QoL is positively related to their caregivers’ QoL [8]. However, there is a lack of research comparing the psychological effects on caregivers of cancer patients versus those of ESKD patients.

In Lebanon, cultural factors present additional challenges for caregivers, as societal expectations often place the responsibility of caregiving on family members, especially on females. It is because, traditionally, women are expected to be the primary nurturers and homemakers. While this family-oriented culture can be great for patients, it often places a disproportionate burden on female family members, potentially limiting their opportunities in other areas of life, such as education and career. In a series of interviews conducted by Doumit et al., caregivers of cancer patients in Lebanon reported living with fear of either contracting the disease themselves or losing their loved ones. These caregivers reported a diminished sense of happiness, living in a state of heightened alertness, and bearing an increased sense of responsibility [9]. In addition, the stigma associated with mental health issues, particularly in some communities within Lebanon, can discourage caregivers from openly expressing their struggles or seeking help. This silence further exacerbates their burden and negatively impacts their well-being. The expectation of “self-sacrifice” for the family, while a source of great devotion and motivation, can often lead to caregiver burnout and neglect of their own needs [10]. Despite the critical role they play, there is limited research on the mental health and QoL of caregivers in this region. This knowledge gap is particularly evident when comparing the psychological impact on caregivers of cancer and ESKD patients. Understanding these differences is crucial for developing targeted interventions to support caregivers effectively.

The primary aim of this study is to assess and compare anxiety, depression, and QoL among caregivers of cancer patients in the daycare unit and ESKD patients in Lebanon, since both groups of patients need frequent transportations to the hospital. We hypothesize that the QoL of caregivers of hemodialysis patients will be lower than that of caregivers of cancer patients. In addition, this study seeks to identify factors associated with the QoL and mental health of these caregivers. By understanding their specific needs and challenges, we aim to propose tailored interventions to improve their mental health and overall well-being.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This is a cross-sectional study conducted at the hemodialysis center and oncology daycare unit of Hôtel Dieu de France University Hospital in Beirut, Lebanon. Data were collected between June 1, 2024, and July 31, 2024. Participants were recruited on the day of their intervention at the hospital (hemodialysis or oncologic treatment). The authors themselves recruited the participants and assisted them in completing all the study tools. Anonymity was ensured, and participants were allowed to withdraw from the study at any time during data collection. All participants provided informed consent before participation.

2.2. Participants

The majority of the participants were close family members of the patients, including parents, siblings, husbands, and spouses. Participants were recruited from the hemodialysis center and the oncology daily treatment center. The inclusion criteria were as follows: being older than 18 years, being capable of providing informed written consent, and having been a caregiver for more than 3 months for someone with cancer or ESKD. Exclusion criteria included participants with a known medical or mental disorder.

- •

Cancer patients: Caregivers of patients with all types of cancer were included. The patients were recruited from the oncology daily treatment center, indicating that they were ambulatory patients receiving chemotherapy, target therapy, and/or immunotherapy as outpatients. No specific cancer stage was defined as an inclusion or exclusion criterion, meaning that patients in different stages of the disease were eligible. Patients receiving palliative care only, without active treatment, were not included as the recruitment took place in a treatment center.

- •

ESKD patients: Caregivers of patients receiving treatment at the hemodialysis center were included. This implies that the patients were undergoing regular hemodialysis sessions, typically two or three times per week, with each session lasting between 3 and 5 h.

2.3. Data Collection

Data were collected through face-to-face interviews between the participants and the authors themselves. This direct interaction encourages more honest and complete responses, minimizes the risk of misinterpretation, and allows immediate clarification. The questionnaire was divided into three parts. The first part gathered sociodemographic information about the study participants, including age, gender, educational level, marital status, address, relationship between the caregiver and the patient whether they worked in the medical field, and personal income.

The second part of the questionnaire focused on the patient’s information, such as age, sex, address, treatment coverage, and their comorbidities. Caregivers of cancer patients were asked specific questions about the cancer type, while caregivers of ESKD patients were asked about the frequency and duration of hemodialysis sessions.

- i.

HADS:

-

The HADS is a questionnaire composed of 14 items, with separate subscales for anxiety (HADS–A) and depression (HADS–D), used in nonpsychiatric people. Each item is rated on a four-point scale (0–3), with scores ranging from 0 to 21 for both anxiety and depression. Scores can be categorized as follows: normal (0–7 points), indicative of possible anxiety or depression (> 8 points), and likely presence of a mood disorder (> 11 points), with a sensitivity of 0.9 and a specificity of 0.86 [11]. The Arabic version of the HADS was used, which has been validated with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83 for the anxiety subscale and 0.77 for the depression subscale [12].

- ii.

WHOQoL–BREF Scale:

-

The WHOQoL–BREF is a 26-item, self-administered questionnaire designed to assess the QoL across four domains: physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environment. In this study, the Arabic version of the WHOQoL–BREF was utilized, which has been validated for reliability and validity in an Arab general population, demonstrating a Cronbach’s alpha of ≥ 0.7. Participants rated their QoL over the preceding 2 weeks on a scale from 1 (very dissatisfied/very poor) to 5 (very satisfied/very good). Domain scores were calculated by summing the raw scores of the constituent items and transforming them into a 0–100 scale, facilitating comparison with other studies [13].

2.4. Flow of the Study

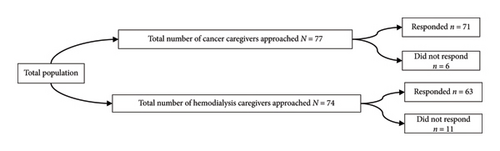

The authors divided their efforts between the hemodialysis center and the day care unit at the Hôtel Dieu de France Hospital, where they approached caregivers accompanying the patients. First, they ensured that the accompanying individual was the patient’s primary caregiver. Among the 77 caregivers of cancer patients approached, 71 agreed to participate in the study. Similarly, out of 74 caregivers of hemodialysis patients, 63 consented to participate. The study flow is illustrated in Figure 1.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Hôtel Dieu de France, Beirut, Lebanon (CEHDF 2428). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Anonymity was ensured for all participants.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic and clinical characteristics of the caregivers and patients, including means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. To compare continuous variables between oncology and hemodialysis caregivers, a one-way ANOVA was employed. For categorical variables, cross-tabulation with chi-square tests was used to examine the relationships between groups. Finally, a multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to assess whether significant factors predicted the caregivers’ QoL. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS 23 software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0., Armonk, New York: IBM Corp).

Sample size: The minimum sample size in each group was calculated as 62 using the equation of n = [Z2 × p × q]/E2, where n is the minimum sample size, Z is the statistic for a level of confidence (1.96), p is the expected prevalence or proportion (20%), q = 1 − p (80%), and E is the margin of error (10%).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Data

A total number of 134 caregivers participated in this study, consisting of 71 caregivers of cancer patients and 63 caregivers of hemodialysis patients, with each caregiver corresponding to one patient. Table 1 presents the demographic and clinical characteristics of the caregivers. Among the participants, 99 were females and 35 were males, with a mean age of 51.72 years (SD = 12.481). The majority of the participants were taking care of their spouse (34.3%) or their child (35.8%). Educationally, 28.4% of the participants held a bachelor’s degree and 32.1% held a master’s degree. Most caregivers did not work in the medical field (91%) and were married (75.4). In terms of employment, 48.5% were unemployed, while 45.5% had full-time jobs. Moreover, most of the participants resided in Beirut (38.8%) and Mount Lebanon (35.8%).

| Combined Mean ± SD N (%) | Oncology (N = 71) Mean ± SD/N (%) | Nephrology (N = 63) Mean ± SD/N (%) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of the caregiver | 51.71 ± 12.48 | 50.45 ± 12.29 | 53.14 ± 12.63 | 0.214 |

| Age of the patient | 63.32 ± 14.95 | 60.09 ± 14.32 | 66.95 ± 14.91 | 0.008 |

| Gender of the caregiver | ||||

| Female | 99 (73.9) | 47 (66.19) | 52 (82.54) | 0.032 |

| Male | 35 (26.1) | 24 (33.8) | 11 (17.46) | |

| Gender of the patient | ||||

| Female | 67 (50) | 44 (61.97) | 23 (36.51) | 0.003 |

| Male | 67 (50) | 27 (38.03) | 40 (63.49) | |

| Relationship between caregiver and patient | ||||

| Spouse | 46 (34.3) | 23 (32.39) | 23 (36.51) | 0.46 |

| Brother/sister | 18 (13.4) | 12 (16.90) | 6 (9.52) | |

| Parent | 14 (10.4) | 7 (9.86) | 7 (11.11) | |

| Son/daughter | 48 (35.8) | 23 (32.39) | 25 (39.68) | |

| Others | 8 (6) | 6 (8.45) | 2 (3.17) | |

| Educational level of the caregiver | ||||

| Not educated | 3 (2.2) | 0 (0) | 3 (4.76) | < 0.001 |

| Complementary studies | 5 (3.7) | 2 (2.82) | 3 (4.76) | |

| Secondary studies | 32 (23.9) | 16 (22.54) | 16 (25.40) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 38 (28.4) | 11 (15.49) | 27 (42.86) | |

| Master’s degree | 43 (32.1) | 30 (42.25) | 13 (20.63) | |

| PhD | 13 (9.7) | 12 (16.90) | 1 (1.59) | |

| Caregiver’s employment status | ||||

| Unemployed | 65 (48.5) | 35 (49.30) | 30 (47.62) | < 0.001 |

| Part-time | 8 (6) | 0 (0) | 8 (12.70) | |

| Full-time | 61 (45.5) | 4 (5.63) | 25 (39.68) | |

| Caregiver’s social status | ||||

| Married | 101 (75.4) | 57 (80.28) | 44 (69.84) | 0.161 |

| Single | 33 (24.6) | 14 (19.72) | 19 (30.16) | |

| Caregiver’s address | ||||

| Beirut | 52 (38.8) | 13 (18.31) | 39 (61.90) | < 0.001 |

| Outside of Beirut | 82 (61.2) | 58 (81.69) | 24 (38.1) | |

| Type of financial coverage | ||||

| Private insurance | 56 (41.79) | 37 (52.11) | 19 (30.16) | < 0.001 |

| Ministry of Health | 22 (16.42) | 4 (5.63) | 18 (28.57) | |

| Personal funds | 32 (23.88) | 31 (43.66) | 1 (1.59) | |

| NSSF | 30 (22.39) | 4 (5.63) | 26 (41.27) | |

| Army | 9 (6.7) | 5 (7.04) | 4 (6.35) | |

| Number of comorbidities (patient) | ||||

| 0 | 5 (3.7) | 3 (4.23) | 2 (3.17) | 0.254 |

| 1 | 94 (70.1) | 53 (74.65) | 39 (61.90) | |

| 2 | 18 (13.4) | 6 (8.45) | 12 (19.05) | |

| 3 | 15 (11.2) | 7 (9.86) | 8 (12.70) | |

| 4 | 2 (1.5) | 2 (2.82) | 0 (0) | |

| WHOQoL–BREF | 233.9752 ± 55.50 | 245.45 ± 48.61 | 210.89 ± 54.02 | 0.0006 |

| HADS–A | ||||

| 0–7 | 27 (19.3) | 14 | 13 | 0.991 |

| 8–10 | 30 (21.4) | 16 | 14 | |

| > 10 | 77 (55) | 41 | 36 | |

| HADS–D | ||||

| 0–7 | 27 (19.3) | 11 | 16 | 0.354 |

| 8–10 | 49 (35) | 28 | 21 | |

| > 10 | 58 (41.4) | 32 | 36 | |

| Frequency of hemodialysis | ||||

| Twice a week | — | — | 21 (33.33) | — |

| 3 times per week | 42 (66.67) | |||

| Duration of each session of hemodialysis | ||||

| 3 h | — | — | 5 (7.9) | — |

| 4 h | 37 (58.73) | |||

| 4.5 h | 14 (22.22) | |||

| > 5 h | 7 (11.11) | |||

| Cancer type | ||||

| Breast | — | 24 (33.8) | — | — |

| Prostate | 3 (4.23) | |||

| Lungs | 5 (6.17) | |||

| Colon | 11 (15.49) | |||

| Lymphoma | 8 (11.27) | |||

| Others ∗ | 20 (24.69) |

- Note: p values were derived from the t-test and chi-square test. N (%), number of participants (percentage of participants). Bold values indicate important statistically significant p values.

- Abbreviations: HADS–A, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale–Anxiety; HADS–D, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale–Depression; Mean ± SD, mean ± standard deviation; NSSF, National Social Security Fund; WHOQoL–BREF, World Health Organization Quality of Life–BREF.

- ∗Others include uterus, leukemia, bladder, multiple myeloma, cerebral, pancreas, cholangiocarcinoma, kidney, and ovarian cancer.

Concerning the patients, their mean age was 63.32 years (SD = 14.851). The patient population was evenly split, with 50% being female and 50% male. A large proportion of the patients (70.1%) had one comorbidity associated with either cancer or end-stage renal kidney disease. Among oncology patients, breast cancer was the most common diagnosis (33.5%), followed by colon cancer (15.49%) and lymphoma (11.27%). Other types of cancer (39.74%) included prostate, lung, bladder, uterine, cerebral and pancreatic cancer, multiple myeloma, and leukemia (Table 1).

Of the total sample, 55% (n = 77) of caregivers had high levels of anxiety and 41.4% (n = 58) of caregivers had high levels of depression. The mean ± SD of the QoL as measured by the WHOQoL–BREF is 233.9752 ± 55.50.

3.2. Comparative Data

The mean score of WHOQoL–BREF for oncology caregivers was 90.83, while for hemodialysis caregivers, it was 79.75, indicating a significant difference in QoL between oncology and nephrology participants, with oncology caregivers reporting a better QoL than nephrology caregivers, as shown in Table 1 (p = 0.0006).

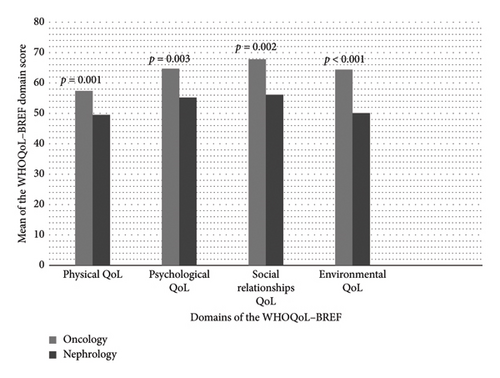

When analyzed according to the four domains of the WHOQoL–BREF, the mean scores for the four domains (physical, psychological, social relationships, and environment) showed significantly lower values for nephrology caregivers compared to oncology caregivers with p values of 0.001, 0.003, 0.002, and < 0.001, respectively (Figure 2).

Regarding anxiety, 57 cancer caregivers and 50 hemodialysis caregivers had a score of eight or more on the HADS–A, indicating probable anxiety. Similarly, concerning depression, 60 cancer caregivers and 57 hemodialysis caregivers had a score of 8 or more on the HADS–D, indicating probable depression. However, no significant difference in anxiety and depression was found between the two groups of participants (Table 1).

3.3. Bivariate Analysis of the QoL

The WHOQoL scores of caregivers varied significantly based on several sociodemographic and clinical variables. Caregivers residing outside Beirut had significantly higher WHOQoL scores (243.996 ± 55.18) compared to those residing in Beirut (218.767 ± 53.41, p = 0.039). Similarly, the type of financial coverage had a significant impact, with caregivers using private insurance or personal funds reporting higher WHOQoL scores (247.54 ± 50.27) compared to those covered by the Ministry of Health, the Army, or the National Social Security Fund (NSSF) (215.63 ± 57.35, p = 0.001) (Table 2).

WHOQoL scores Mean ± SD |

p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Address of the caregiver | Beirut (N = 52) | 218.767 ± 53.41 | 0.039 |

| Outside of Beirut (N = 81) | 243.996 ± 55.18 | ||

| Type of financial coverage | Private insurance and/or personal funds (N = 77) | 247.54 ± 50.27 | 0.001 |

| Ministry of Health and/or army and/or NSSF (N = 57) | 215.63 ± 57.35 | ||

| HADS–D | ≥ 11 (N = 107) | 229.09 ± 53.92 | 0.042 |

| < 11 (N = 27) | 253.32 ± 58.42 | ||

| HADS–A | ≥ 11 (N = 107) | 227.67 ± 52.35 | 0.008 |

| < 11 (N = 27) | 258.92 ± 61.42 | ||

| Number of comorbidities | ≥ 3 (N = 17) | 259.83 ± 61.61 | 0.039 |

| < 3 (N = 117) | 230.21 ± 53.81 | ||

| Gender of the patient | Female (N = 67) | 246.02 ± 49.02 | 0.011 |

| Male (N = 67) | 221.92 ± 59.23 | ||

| Social status of the caregiver | Married (N = 101) | 237.30 ± 56.03 | 0.226 |

| Single (N = 33) | 223.79 ± 53.36 | ||

| Employment status of the caregiver | Employed (N = 69) | 237.61 ± 54.68 | 0.437 |

| Unemployed (N = 65) | 230.11 ± 56.52 | ||

| Educational level of the caregiver | < University degree (N = 40) | 209.65 ± 53.33 | 0.001 |

| ≥ University degree (N = 94) | 244.32 ± 53.38 | ||

| Gender of the caregiver | Female (N = 99) | 231.92 ± 56.73 | 0.474 |

| Male (N = 35) | 239.77 ± 52.21 | ||

| Frequency of hemodialysis | 2 times per week | 201.60 ± 48.41 | 0.338 |

| 3 times per week | 215.54 ± 56.60 | ||

| Duration of each session of hemodialysis | < 4.5 h | 208.17 ± 56.52 | 0.576 |

| ≥ 4.5 h | 216.34 ± 49.51 | ||

- Note: p values were derived from the t-test. Bold values indicate statistically significant p values.

- Abbreviation: NSSF, National Social Security Fund.

The caregivers’ depression (HADS–D) and anxiety (HADS–A) levels also showed a significant association with QoL. Caregivers with lower HADS–D scores (< 11) had significantly higher WHOQoL scores (253.32 ± 58.42) compared to those with higher scores (≥ 11: 229.09 ± 53.92, p = 0.042). Similarly, caregivers with lower HADS–A scores (< 11) exhibited better WHOQoL scores (258.92 ± 61.42) than those with higher scores (≥ 11: 227.67 ± 52.35, p = 0.008) (Table 2).

The number of comorbidities in caregivers also affected their QoL, with those having fewer comorbidities (< 3) reporting higher WHOQoL scores (230.21 ± 53.81) compared to those with three or more comorbidities (159.83 ± 61.61, p = 0.039). Gender of the patient also influenced caregiver’s QoL, with those caring for female patients reporting higher WHOQoL scores (246.02 ± 49.02) compared to those caring for male patients (221.92 ± 59.23, p = 0.011). However, caregivers’ marital status (p = 0.226), employment status (p = 0.437), and gender (p = 0.474) were not significantly associated with WHOQoL scores (Table 2).

In addition, the caregivers’ educational level showed a significant relationship with QoL. Those with a university degree or higher reported higher WHOQoL scores (244.32 ± 53.38) compared to those with less than a university degree (209.65 ± 53.33, p = 0.001) (Table 2).

Lastly, caregivers of patients undergoing three hemodialysis sessions per week or sessions lasting 4.5 h or more, reported higher WHOQoL scores compared to those of patients undergoing two sessions per week or each session lasting less than 4.5 h, though the difference was not statistically significant.

3.4. Multivariate Analysis

A multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to examine whether the caregiver’s residence, educational level, employment status, anxiety and depression levels (assessed by the HADS scale), the patient’s number of comorbidities, and the type of financial coverage significantly predicted the variability of the caregiver’s QoL.

The overall regression model was statistically significant (R2 = 0.290, F [9, 126] = 7.751, p < 0.001). The caregiver’s educational level (β = 0.209, p = 0.010), anxiety level (β = −0.231, p = 0.006), the patient’s number of comorbidities (β = 0.199, p = 0.007), and whether the patient belongs to the nephrology or oncology group (β = −0.350, p = 0.001) were significant predictors of the caregiver’s overall QoL, as assessed by the WHOQoL–BREF (Table 3). The results indicated that a higher caregiver educational level and an increased number of patient comorbidities, along with lower levels of caregiver anxiety, were associated with an improved QoL for the caregiver. In addition, nephrology caregivers suffered from a worse QoL compared to cancer caregivers.

| Variables | R-square = 0.360 | F = 7.751 | p < 0.001 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized coefficients | t | p value | |

| Beta | |||

| Oncology or nephrology group | −0.350 | −3.463 | 0.001 |

| Address of the caregiver | −0.025 | −0.301 | 0.764 |

| Type of financial coverage | −0.001 | −0.15 | 0.988 |

| Educational level of the caregiver | 0.209 | 2.602 | 0.010 |

| Gender of the caregiver | −0.105 | −1.373 | 0.172 |

| HADS–A | −2.31 | −2.807 | 0.006 |

| HADS–D | −0.142 | −1.748 | 0.083 |

| Patient’s number of comorbidities | 0.199 | 2.721 | 0.007 |

- Note: Beta, standardized coefficient; R-square, coefficient of determination. Bold values indicate statistically significant p values.

However, the remaining variables did not significantly predict the caregiver’s overall QoL.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the QoL, depression, and anxiety between the caregivers of cancer and ESKD patients. In addition, this is the first study in Lebanon to assess the QoL, depression, and anxiety in the caregivers of cancer and end-stage renal failure disease patients. The main finding of our study is that caregivers of cancer patients tend to have a better QoL than those caring for ESKD patients.

Most of the caregivers enrolled in our study experienced a bad QoL and high levels of anxiety and depression. According to Zyada et al. [14], changes in caregivers’ plans about the future or expectations may partially explain this emotional burden. However, despite elevated levels of anxiety and depression among caregivers in both groups, there was no significant difference in anxiety and depression levels between cancer and renal caregivers. This finding is in line with the findings of Nipp et al. [15]. Thus, given that QoL is defined as an individual’s subjective perception of life [16], assessing a caregiver’s well-being should not rely solely on anxio-depressive symptoms but should also consider other life domains, such as family and social support, access to healthcare services, adequate transportation, and sufficient financial resources to meet one’s needs.

Our study showed that caregivers of hemodialysis patients reported significantly lower QoL scores compared to cancer caregivers (p = 0.0006). Several factors could explain the observed differences in QoL between cancer and ESKD caregivers. First, the nature of the disease itself plays a role. Patients with ESKD often have a worse QoL than cancer patients. This could be because ESKD is a chronic condition with an unpredictable course. It requires regular, frequent trips to dialysis centers, usually 2-3 times a week for 3–5 h per session, which disrupts both the caregiver’s work and personal life [7]. Cancer, on the other hand, tends to follow a more defined path, with periods of treatment, potential remission, or end-of-life care, which allows for more planning and access to resources [17].

In addition, in our analysis, cancer patients were generally younger than kidney disease patients. Younger patients may be better at handling stress and adapting to their situation, often by seeking out information and support, which could help reduce the burden on their caregivers [18].

Furthermore, cancer caregivers may have access to more social and emotional support because cancer is widely recognized as a serious, life-threatening illness. In Lebanon, it is even referred to as “the disease” by many people [19]. On the other hand, ESKD is less known and may not generate the same level of awareness or support from society.

As a result of these challenges, caregivers of nephrology patients often face greater difficulties across various life domains. This is reflected in the significantly lower scores across the WHOQoL–BREF domains for nephrology caregivers, particularly in physical, psychological, social, and environmental aspects.

To alleviate the physical and social strain on these caregivers, hospitals or relevant organizations could assume the responsibility of providing transportation to the dialysis unit. While this approach might also be beneficial for cancer patients, hemodialysis patients typically require more frequent treatment sessions, making them particularly in need of such services. This transportation service would reduce the physical demands on caregivers, thereby freeing up time and energy for social interactions and personal activities.

Addressing the psychological strain is equally important. Healthcare professionals can evaluate patients’ coping styles and employ cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT) to address negative coping mechanisms. This approach empowers patients to adopt healthier strategies for managing their condition, which in turn reduces the stress placed on caregivers. Moreover, family resilience plays a significant role in caregiver well-being. Family counseling can improve communication, strengthen relationships, and foster collaborative coping mechanisms [20].

Family counseling also provides a structured and supportive environment where family members can communicate more openly and effectively. This is especially important in the context of chronic illness, where stress, fear, or a desire to protect loved ones can stifle open dialog. By facilitating understanding and empathy within the family, counseling can help strengthen bonds and create a more cohesive unit better equipped to handle caregiving challenges together. Distributing caregiving duties with family members lightens the load, highlighting the essential role of family support in easing both the physical and psychological demands on the caregiver [21].

In the multivariate analysis, the caregiver’s educational level, anxiety level, and the patient’s number of comorbidities significantly predicted the caregiver’s overall QoL.

First, a higher number of comorbidities in patients was associated with an improved QoL for caregivers. In fact, research indicates that patients with multiple comorbidities often receive better care [21, 22]. However, our finding contradicts previous studies, where increased patient comorbidities are associated with greater caregiver burden [23]. This may be due to Lebanon’s collectivist society, where caregiving responsibilities are often distributed among multiple family members, particularly when a patient has multiple comorbidities. As the severity of illness increases, more family members become involved, ensuring that caregiving duties are shared rather than falling solely on one individual. This redistribution of tasks reduces the physical and psychological strain on any single caregiver, potentially leading to lower perceived stress and an overall better QoL.

Second, caregivers with higher levels of education consistently report a better QoL, a relationship well-supported by research [24]. This can be explained by several key factors that education positively influences.

One of the most significant factors is health literacy. Educated caregivers often have a deeper understanding of their loved one’s illness, which allows them to manage the patient’s therapeutic needs more effectively. This greater understanding reduces uncertainty, leading to a stronger sense of control, which in turn decreases anxiety and enhances overall well-being [24].

In addition, education strengthens critical thinking and problem-solving skills, which are crucial for navigating the complexities of the healthcare system. Caregivers equipped with these abilities are better positioned to identify and implement effective coping strategies, whether by building a support network, seeking professional advice, or researching new information. This proactive approach to caregiving not only alleviates the burden but also fosters a sense of empowerment [24]. Furthermore, education enhances caregivers’ confidence in communicating with healthcare providers, making them more likely to ask important questions, seek second opinions, and advocate for the patient’s needs.

In addition, caregivers with higher education levels are more likely to have stable jobs that offer benefits such as paid leave or flexible work schedules, enabling them to manage caregiving responsibilities without significant financial stress. Importantly, it is not just about earning a higher income but about having a consistent and reliable source of financial support, which significantly reduces stress [25].

Furthermore, caregivers with high educational attainment have increased autonomy and a greater awareness of the importance of taking care of their own mental health and QoL [26].

Third, regarding the HADS, only anxiety has been found to be a predictor of QoL, with higher HADS–A scores correlating with a diminished WHOQoL score. Other studies have reported similar findings regarding anxiety but contrary results concerning depression [27, 28]. In fact, elevated anxiety increases cognitive load, making it harder for caregivers to manage their responsibilities effectively [16]. This can lead to failure in adapting to the demands of this chronic treatment, heightened frustration, and isolation, all of which negatively impact QoL [29].

Although depression was significantly linked to lower QoL when considered on its own in our bivariate analysis, it did not emerge as a significant independent predictor in the multivariate model. This might be explained by the strong connection between anxiety and depression in our caregiver sample. Interestingly, we found that the same number of caregivers (N = 117) scored high for both anxiety (HADS–A ≥ 11) and depression (HADS–D ≥ 11). This considerable overlap suggests that for many caregivers in our study, depressive feelings may be intertwined with, and perhaps contribute to, heightened anxiety. It is plausible that this anxiety then becomes the more immediate factor directly impacting their daily lives and overall QoL.

Concerning the address of the caregivers, the bivariate analysis showed that those living outside Beirut experience a higher QoL than those in the city. In fact, research suggests that rural caregivers benefit from quieter surroundings, lower stress, stronger community ties, and greater social support. These factors enhance mental and physical well-being, while urban caregivers face congestion, isolation, and higher stress [30, 31].

In addition , the healthcare system in Lebanon plays an essential role in the QoL of caregivers. Our bivariate analysis showed that those who use private insurance or pay directly out-of-pocket report a better QoL compared to those who must rely on the NSSF or the Ministry of Public Health. This disparity is a direct reflection of the severe crisis crippling Lebanon’s healthcare system.

Lebanon is facing an economic crisis of immense proportions. Inflation reached a staggering 172% in 2023. The World Bank has classified this as one of the top 10 most significant global economic crises since the mid-19th century. This economic collapse has had a devastating effect on public institutions, including those responsible for healthcare [32].

The financial resources of public healthcare funds such as the NSSF have been decimated. Where the NSSF was intended to provide social security, it now covers a mere 10% of healthcare costs. This leaves patients and their families to pay for the overwhelming majority, 90%, out of their own pockets. As a result, out-of-pocket healthcare expenditures in Lebanon have skyrocketed to over 85% of household income. It is estimated that more than half of the Lebanese population currently lacks any meaningful healthcare coverage [32].

In this broken system, caregivers who can access private healthcare through insurance or direct payment find themselves in a comparatively better situation. They are more likely to secure timely appointments, treatments, and necessary medications and hospitalizations. This contrasts sharply with caregivers navigating the public system, who face delays, shortages, bureaucratic hurdles, and immense financial strain [32]. The ability to access private healthcare, though costly, becomes a significant factor in maintaining a better QoL for caregivers in crisis-stricken Lebanon.

Furthermore, caregivers of female patients often report a better QoL compared to those caring for male patients. This may be because women are generally more open about their emotional needs, allowing for better communication, stronger social support, and shared decision-making. On the other hand, male patients tend to be less expressive which may increase caregiver stress and burden. As a result, caregivers may find it easier to cope and feel less emotionally overwhelmed when supporting female patients [33].

Given that the number of cancer patients or patients undergoing hemodialysis is expanding at an alarming rate, it is obvious that the burden of caregivers is expected to increase [34, 35]. Thus, healthcare workers should put an emphasis on evaluating caregivers’ psychological well-being.

Support from family has been consistently associated with better health outcomes in chronic illness, regardless of geographic or ethnic differences, highlighting the importance of maintaining healthy caregivers as a valuable resource for patients. Although significant progress has been made in recent years in understanding psychiatric disorders in hemodialysis and cancer patients, caregivers still require more focused attention, including regular diagnostic evaluations. Educational interventions tailored to caregivers’ needs represent a growing area of interest and could significantly reduce the economic, medical, personal, and social burdens related to hemodialysis and cancer [36]. Gaining a deeper understanding of the factors that affect caregivers’ QoL is essential for planning future, effective interventions to support this vulnerable group.

4.1. Limitations of the Study

First, this study was cross-sectional, and therefore, we were unable to identify definite causal relationships between the mentioned factors and the caregivers’ QoL. Second, concerning the cancer population, since the study was conducted at a cancer daycare center, most of the cancer patients whose caregivers were included in our study were ambulatory and had a good performance status. This limits the generalizability of our findings to caregivers of patients with more advanced or terminal cancer stages. In addition , the sample size presents a limitation, as a larger sample could provide more robust and generalizable findings.

5. Conclusion

This study shows that caregivers of both cancer and ESKD patients in Lebanon face significant challenges impacting their QoL, with ESKD caregivers experiencing a demonstrably poorer QoL compared to cancer caregivers. To tangibly improve the QoL for caregivers across both conditions, we strongly advocate for policies aimed at achieving universal healthcare coverage to reduce the financial burden on caregivers and ensure equitable access to care, irrespective of socioeconomic status.

Beyond systemic financial reforms, targeted interventions are crucial. For policy, this translates to the implementation of national caregiver support programs that integrate mental health services and accessible educational resources. Furthermore, recognizing the unique challenges faced by ESKD caregivers, policy should mandate the development of specialized support services for this group, potentially including subsidized transportation to dialysis centers. Finally, to ensure sustainable improvement, healthcare policy must integrate routine assessment of caregiver well-being into patient care plans for both cancer and ESKD, enabling early identification of at-risk caregivers and facilitating timely access to necessary support services.

At its core, the act of caregiving embodies one of the most profound expressions of human solidarity. Yet, when this burden is carried in isolation, the weight of this responsibility can become overwhelming, leaving caregivers emotionally and physically drained. A just society is one that does not merely recognize suffering but actively seeks to alleviate it, understanding that the measure of its moral progress lies in how it supports those who give of themselves for others.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.