The Perceptions of Patients, Carers and Clinicians Relating to SACT Decision-Making in Older People With Cancer: Qualitative Findings From the Electronic Frailty Index (eFI) in Cancer Study

Abstract

Objective: To explore the perceptions and experiences of patients, carers and clinicians relating to treatment decision-making in older people with cancer, and to investigate the acceptability of the eFI as a tool to influence decisions about SACT.

Methods: Qualitative interviews were conducted with 28 participants (12 clinicians, 10 patients and 6 carers) at an NHS cancer day unit in South East England. Patients were > 60 years and had received at least one cycle of SACT. Data were analysed using framework analysis.

Results: Two themes were identified. Theme one highlighted that the assessment of frailty is a variable and complex task. However, an individualised assessment incorporating a balance between quality of life and the potential benefit of treatment is fundamentally important. Theme two identified that eFI is an acceptable addition to SACT decision-making which must be discussed with the patient and considered within the context of each individual situation.

Conclusion: The eFI is acceptable for use in assessing the frailty of older people with cancer prior to starting SACT. In-depth, individualised assessment prior to SACT is important in this population, but it is not always realistic. Incorporating the eFI into SACT decision-making offers the potential to address this challenge.

1. Introduction

The decision to treat older people with cancer is multifaceted and complex. Evidence shows that older people with cancer are less likely to undergo systemic anti-cancer treatment (SACT) than their younger counterparts, regardless of their baseline fitness or tumour characteristics [1]. At the same time, we know that those who are older and have a higher degree of frailty are more likely to experience harm as a result of their treatment [2]. Frailty can be defined as a long-term health condition that is characterised by loss of physical, emotional and cognitive function, and people living with frailty are more vulnerable to adverse health outcomes and loss of independence [3].

At present, performance status (PS) is commonly used in the United Kingdom as a means of assessing fitness for SACT treatment. Whilst PS has benefits in terms of being widely recognised and relatively simple to use, it does not always offer an accurate representation of health and wellbeing [4].

The electronic Frailty Index (eFI) is used in primary care in England to identify whether a person is likely to be fit or living with mild, moderate or severe frailty (Supporting Information (available here)). It uses routine health record data to automatically calculate a score to identify who may be at greatest risk of adverse outcomes as a result of their underlying health conditions and care needs. The eFI uses a “cumulative deficit” model to measure frailty on the basis of the accumulation of a range of 36 deficits. These deficits include clinical signs (e.g., tremor), symptoms (e.g., vision problems), diseases, disabilities and abnormal test values [3].

Our “eFI in cancer” study adopted a mixed methods approach to investigate the potential utility of the eFI to predict adverse outcomes of SACT in frail, older (> 70 years) people with breast, colon or non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). This paper focuses on findings from the qualitative substudy.

The aim of this substudy was to investigate the acceptability of eFI as a tool in assessing frailty in cancer patients and influencing clinical decision-making over SACT treatment from the perspectives of patients, carers and health professionals (HPs). To address this objective, a qualitative approach was adopted which included an exploration of the experiences and perceptions of patients, carers and clinicians relating to their diagnosis and subsequent treatment. The study has been designed and reported in accordance with the CASP quality appraisal checklist for qualitative studies [5] (Supporting Information). The study was reviewed and given a favourable opinion by the Wales 6 Research Ethics Committee (ref: 20/WA/0284).

2. Methods

2.1. Recruitment

Patients attending an NHS cancer day unit with lung, colorectal or breast cancer who had received at least one cycle of SACT and were over the age of 60 were identified by their oncologist and screened by the principal investigator (PI) prior to being contacted by the research associate (RA) and offered further information on the study. The RA was external to the clinical team and was not involved in the ongoing care of the patients. Carers were approached over the telephone by the RA with the patient’s consent and were sent the information sheet either through the post or via email. HPs were initially approached by the PI, who provided them with the study information sheet and invited them to participate. We aimed to recruit at least 10 HPs, 10 patients and 5 carers. This sample size was deemed to be sufficiently large enough to ensure information power, whilst at the same time remaining manageable within the scope of the study [6]. Recruitment occurred from January to June 2022.

2.2. Data Collection

Following agreement, participants were given the choice of either a video interview via Microsoft Teams or a telephone interview. At the start of each interview, the researcher obtained verbal consent from the participant by talking through the consent form and asking them to confirm their name and agree or disagree with each statement. Interviews lasted between 28 and 45 min. Predetermined topic guides (Supporting Information) were used in the interviews, which ensured that all relevant subjects were covered but also incorporated a degree of flexibility to allow individuals to discuss issues that were most important to them.

2.3. Data Analysis

Interview transcriptions were either downloaded directly from MS Teams or performed by a university-approved transcription company. All interview transcriptions were anonymised using identification numbers and stored on the password-protected university server. NVivo (R1.6) software was used to facilitate data analysis and storage. Data were analysed thematically using framework analysis [7]. Both the original audio recordings and the transcriptions were revisited on multiple occasions to aid familiarisation with the data. Line-by-line coding was then undertaken to identify emerging themes/codes. These themes were then reviewed and merged wherever possible, before being grouped into two overall categories [8]. KS and JA reviewed and compared theme findings to ensure congruence. In order to preserve anonymity, each participant was allocated an ID number with a letter denoting their group (P for patients, C for carers and HP for health professionals/clinicians).

3. Results

Twelve interviews with clinicians were conducted between September and December 2021. Table 1 shows the professional roles of these interviewees.

| ID number | Role |

|---|---|

| HP1 | Clinical nurse specialist (palliative care) |

| HP2 | Clinical nurse specialist (cancer) |

| HP3 | Clinical oncologist |

| HP4 | Clinical nurse specialist (cancer) |

| HP5 | Palliative care consultant |

| HP6 | Geriatrician |

| HP7 | Clinical nurse specialist (cancer) |

| HP8 | GP |

| HP9 | Medical oncologist |

| HP10 | GP |

| HP11 | GP |

| HP12 | Clinical nurse specialist (cancer) |

Twelve patients were approached regarding participation in the study. One felt too unwell to be interviewed and another did not respond. The remaining 10 patients were interviewed between January and June 2022. None of the patients reported significant health problems prior to their diagnosis. Most commented that they had felt fit and healthy and were exercising regularly. The profiles of the patient participants can be seen in Table 2.

| ID number | Gender | Age at interview | Cancer type | Treatment | Marital status | Employment status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | F | 68 | NSCLC | Pemetrexed | Married | Retired |

| P2 | F | 71 | Breast | Carboplatin | Married | Retired |

| P3 | M | 79 | Colorectal | FOLFIRI | Married | Retired |

| P4 | F | 75 | Colorectal | FOLFIRI | Married | Retired |

| P5 | F | 64 | Colorectal | FOLFOX | Married | Retired |

| P6 | F | 69 | Colorectal | FOLFOX | Single | Employed |

| P7 | F | 76 | Lung | Osimertinib | Married | Retired |

| P8 | F | 73 | Breast | Paclitaxel | Married | Retired |

| P9 | F | 76 | Breast | Paclitaxel | Married | Retired |

| P10 | F | 63 | Breast | Paclitaxel | Married | Employed |

Six carers were approached via their partners. They were given information on the study and asked if they would consider being involved. One chose not to participate. The interviews with carers were conducted between January 2022 and July 2022. Table 3 provides details of the carers recruited to the study.

| ID number | Gender | Relationship to patient | Patient’s cancer type |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | M | Husband | NSCLC |

| C2 | F | Wife | Colorectal |

| C3 | M | Husband | Colorectal |

| C4 | M | Husband | Breast |

| C5 | M | Partner | Breast |

The analysis of the data resulted in the development of three themes each with associated subthemes (Table 4). The quotes deemed to be most representative of the themes are presented below. Additional quotes for all themes can be found in the additional quotes table (Supporting Information).

| Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Assessment/decision-making | 1. Initial assessment (assessment of frailty/impressions of performance status) |

| 2. SACT decision-making (factors involved, information giving and discussion of treatment options) | |

| 3. “Just get on with it” | |

| Efi | 1. First impressions of eFI |

| 2. Concerns about the deficits | |

| 3. Discussing eFI with patients and families | |

| 4. Implementation (timing) | |

| 5. Thoughts on the use of the term “frailty” in relation to the eFI | |

4. Theme One: Assessment/Decision-Making

4.1. Initial Assessment

4.1.1. Assessment of Frailty

There was an overwhelming sense from all participants that the assessment of frailty is a highly complex task which is complicated by the fact that individuals cope with varying degrees of frailty in different ways. HP6 commented that frailty assessments were complex and unique to each patient, as some may have multimorbidities but present as non-frail and vice versa. HP9 and HP10 also felt that assessing frailty was multidimensional and required close consideration of each individual situation.

When someone walks in the room you’re doing the assessment straightaway. Can they walk? Are they in a wheelchair and what are they like? All of that going on just as you call their name to get them in the room…I mean, that’s just part of what we’re doing, but I don’t think it gets any more individualized than you know they’re quite sprightly. They’re up and about they’re doing things during the day or no, they’re sort of stuck in bed the whole time…HP12

4.1.2. Impressions of PS

So when you used to do it in the past…you could see whether they could walk into clinic, if they could walk from the blood room or to have a coffee. You could see their performance status a lot better and a lot of it’s now done over the phone. You know the doctors are putting PS1 because the patient reflects on how they used to be, not how they are. HP7

I’ve heard patients be told ‘Make sure you know when you go and see the oncology consultant.’ Make sure you’re looking smart and make sure that, you know, you’ve got your makeup on and all the rest of it…HP1

Interestingly, two clinicians commented on the “grey areas” of a PS score, with the use of brackets and slashes (e.g., PS2/3) being commonplace and seeming to represent a difficulty in making an accurate and definitive assessment.

4.2. SACT Decision-Making

4.2.1. Factors Involved in Decision-Making

I did mention it a couple of weeks ago when I saw one of the oncology team and I said, “Well if it’s going to benefit me for quite a long time, it probably would be worth doing, but if it only sort of…” Bearing in mind I’m 80, whether I want to be going through all that. I’m fed up with pain, I’m fed up with side effects and swollen ankles and everything. It sounds as if I’m vain, it’s not that…I’m just fed up with what’s happened to me basically. And I just feel ‘do I really want to fuss about anything else or just carry on what I’m doing and to see what happens?’ P7

It’s really the 70-80-year-olds at home by themselves on chemo because when it falls apart, there’s nobody there for them. You know, and even when they have somebody at home, and you talk to them. And they’ve got their husband there with them, but their husband is perhaps 81 and hard of hearing. It becomes such a stressful situation for them, and I think that that’s definitely missed in the assessment of these patients is that home support…HP7

HP3, HP4 and HP5 felt that the decision-making process often included an element of professional experience or a “gut feeling” (HP3).

4.2.2. Information Giving and Discussion of Treatment Options

How much information people liked to be given regarding SACT was variable. Five patients wanted as much information as possible. They said it helped them to be prepared and to retain a degree of control. They also felt that it was good to know the potential risks of treatment. Patients generally spoke positively of the written information they were given, as they could read and digest it at their own pace. However, three patients said they felt overwhelmed by the volume of information they received. None of the patients recalled being offered an alternative treatment to SACT, and they were generally happy to accept the clinician’s recommendation.

4.3. “Just Get on With It”

Well, at that point, I just wanted to get on with it, whatever information they gave me. I didn’t want to hang around. I mean, you think it’s spreading everywhere which I’m sure it must have done during that time. But that was the main thing, just get the treatment started… I would have consented to anything just to get it moving. P1

5. Theme Two: The eFI

5.1. First Impressions of the eFI

The eFI was generally seen as an acceptable addition to the decision-making process across all groups of participants. Clinicians thought it was a useful tool, especially for professionals at the MDT who had not seen the patient beforehand. HP7 suggested that it may help to highlight pre-existing conditions that might otherwise be missed. The inclusion of nonphysical issues such as social vulnerability was also seen as a positive step. HP2 and HP7 both felt that it was an improvement on PS as it is more detailed and specific.

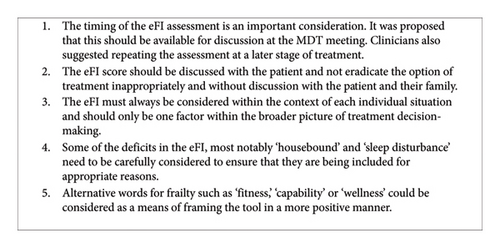

Despite this positive response, some important concerns were expressed which need to be taken into consideration. Two clinicians expressed concerns about the quality of the data being used to generate the eFI. They were aware of inconsistencies in these data and felt there was a risk that this would affect the accuracy of the eFI outcome. Other concerns highlighted by the participants were that the score must be discussed with the patient and not eradicate the option of treatment inappropriately, that the eFI must always be considered within the context of each individual situation and should only be one factor within the broader picture of individual clinical decision-making.

5.2. Concerns About the Deficits

Three participants questioned the relevance of the “sleep disturbance” deficit, as it was felt that this could be caused by a variety of issues. For example, patients may have well-disrupted sleep as a result of anxiety regarding their diagnosis and potential treatment, which would be a very different situation to sleep disturbance resulting from cancer-induced symptoms such as pain or a cough.

You might find actually being housebound is less important because there are so many reasons why they might be housebound. They might be agoraphobic, they might be stuck upstairs cause the lifts don’t work, and so what you might find is actually there might be those. You know, those ones that need greater weight within this…HP3

5.3. Discussing eFI With Patients and Families

I suppose again it’s about maybe saying to them, you know we want to see whether chemo really is the best option… or whether it’s going to bring you more problems than not. HP1

C2 thought it was important that the eFI was described as an aid to personalised decision-making, rather than an assessment tool, which might make people feel that they were being negatively judged.

5.4. Implementation (Timing)

HP5 commented on the benefit of the score being automatically generated, as if it needed to be calculated by clinicians, then it was unlikely to be done due to time pressures. However, four clinicians, two carers and three patients thought that the patient, carer and clinician should go through the score together, and possibly give the patient a copy to look at beforehand.

There was considerable discussion on the timing of the eFI assessment. Four clinicians thought that the eFI score should be available in time for the multi-disciplinary team meeting (MDT). HP11 thought it should be done prior to investigations so that it is known from the start whether or not a patient will ever be a candidate for SACT. Three clinicians thought that the eFI would need to be reassessed throughout SACT treatment to monitor for any changes in fitness.

5.5. Thoughts on the Use of the Term “Frailty” in Relation to the eFI

When you said that the other day I was horrified! I don’t class myself as frail at all, certainly not. P1

Four participants said they did not object to the term, but some of these went on to say that they would not want it applied to them. Participants said that frailty evoked an image of someone who was “immobile”, “very old” and “walking with a zimmer or walking stick”.

I’m happy to discuss frailty or use the word frailty. My patient group most likely will be elderly so… I’m sure this word has been used many times with them. HP2

HP8 said he would use the term with family if a patient was immobile to explain treatment decisions but not with the patient themselves. In total, three HPs said they would not use the term “frailty” directly with patients and were more likely to use phrases such as “you’re a bit more delicate than you used to be”.

6. Discussion

Our study has offered an in-depth exploration of the perceptions of patients, carers and clinicians relating to SACT decision-making in older people with cancer. Some participants felt that QoL was more important than survival. This is a concept that has been identified elsewhere, particularly as this population are less likely to see survival gains than their younger counterparts [9–11]. This finding emphasises the importance of discussing the potential impact of SACT on QoL with patients as part of the decision-making process, as well as presenting appropriate alternatives to SACT as valid treatment options.

Participants highlighted the value of a thorough individualised assessment prior to commencing treatment. However, clinicians commented that the assessment of frailty is time-consuming and multifactorial, an issue that has been acknowledged previously [12]. In current oncology practice, PS is widely used as a means of assessing a person’s fitness for treatment [13]. Participants in our study suggested that although PS is useful in terms of its speed and familiarity, it is limited in its ability to provide a comprehensive and individualised assessment.

There is increasing support for more specialised oncogeriatric care and assessment of older people with cancer [11, 12, 14]. This is even more important considering the evidence from our study that participants were likely to accept the recommendations of their clinician when it came to making a decision about treatment. Similar findings have been identified elsewhere [15], and these findings emphasised the fundamental importance of treatment decision-making based on a thorough and holistic assessment of each individual. Unfortunately, such an in-depth assessment may not always be realistic within the context of increasingly overstretched healthcare providers [16]. Our study showed that the eFI offers a potential solution to bridge the gap between PS and more detailed geriatric assessment and allows for the considerable heterogeneity in the physical health and functioning of older people to be taken into account as part of the treatment decision-making process [11, 17].

Our study revealed that the term “frailty” has negative connotations for some older people. Alternative words such as “fitness”, “capability” or “wellness” were suggested and could be considered as a means of framing the tool in a more positive manner. These findings echo those of Pan et al. [18], who also found that using the term with older adults may have negative consequences. Participants in Pan et al.’s study [18] rejected the idea that they were frail themselves and preferred the use of more positive communication focused on resilience and autonomy. Our findings reinforce the importance of cautious use of the term “frailty”, particularly in conversations with older adults who may perceive it to be a derogatory label.

Figure 1 summarises the key recommendations from our study relating to the implementation of the eFI as a tool in treatment decision-making in older people with cancer.

A potential limitation of our study was that participants were asked to consider the potential value of the eFI in decision-making retrospectively. Further research involving a prospective study on the use of eFI in SACT decision-making in older people with cancer would reduce the risk of recall bias. However, the retrospective nature of our study could also be viewed as advantageous in the sense that it allowed patients and carers to reflect on whether or not they would alter aspects of the decision-making process in hindsight.

7. Conclusion

This study has found that the eFI is acceptable for use in assessing the frailty of older people with cancer prior to starting SACT treatment. Participants thought that it could be a valuable addition to the decision-making process and would encourage a more individualised approach. However, this study has highlighted some important issues which should be taken into consideration to ensure that it is used in a way that is acceptable to patients, carers and HPs. We identified interesting themes relating to the broader issue of SACT decision-making in older people with cancer. We found that both patients and clinicians place a high value on an individualised assessment prior to making a treatment decision. However, this is often a time-consuming process. The tension between preserving QoL and increasing survival is fraught with emotional, mental and physical challenges but is a particularly important consideration in this population. Incorporating the eFI into SACT decision-making offers the potential to address these challenges and to improve the experiences of older people with cancer.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (Research for Patient Benefit). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the considerable contribution of Jennie Huynh, Margreet Luchtenborg and Elizabeth Ford to the ‘eFI in Cancer’ study. We would also like to thank the patients, carers and health professionals who gave their time to be interviewed.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.