Experiences of Patients With Cancer With the Facilitators of and Barriers to Preoperative Physical Activity: A Qualitative Systematic Review

Abstract

Purpose: To explore the experiences of patients with cancer with preoperative physical activity.

Methods: A systematic literature search was conducted on CINAHL, MEDLINE, Scopus and PsycINFO in February 2025. 31 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were selected for analysis. The data were subjected to inductive content analysis.

Results: There is great variation in preoperative physical activity guidance, the content of physical activity, the physical exercises performed and the amount and duration of physical training. Preoperative physical activity is facilitated by the experience of increased well-being, the experience of improved coping with cancer, the experience of the importance of physical activity, social support and physical activity resources. Preoperative physical activity is limited by health limitations, inadequate knowledge about physical activity, a negative attitude towards physical activity and inadequate physical activity resources.

Conclusion: Healthcare professionals should discuss physical activity with patients diagnosed with cancer as part of cancer treatment. Furthermore, patients should be provided with information on the health and well-being benefits of preoperative physical activity and offered an opportunity to participate in physical activity programs that reflect their personal characteristics, preferences and available physical activity resources.

1. Introduction

Cancer is a common disease globally [1]. In 2022, close to 20 million new cancer cases were estimated to have occurred, and the number of new cases will continue to increase worldwide. In 2050, 35 million new cancer cases are predicted [2]. Over 80% of cancer cases require surgery [3]. In this qualitative systematic review, physical activity was defined as encompassing both work-related and leisure-time physical activity, as well as exercise [4]. It included both participation in supervised physical activity programs and engagement in unsupervised physical activity independently. According to the recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO) [5], adult patients with cancer should weekly perform a minimum of 150–300 min of moderate-intensity or at least 75–150 min of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity or a combination of these to achieve health benefits. Additionally, patients should perform muscle-strengthening activities a minimum of twice a week. Older patients should furthermore perform functional balance and strength-training exercises at least 3 days a week [5]. However, studies have shown that patients with cancer do not always receive adequate guidance on preoperative exercise [6] and preoperative physical activity is, indeed, often inadequate in patients with cancer who exercise on their own [7, 8]. Experimental information on the preoperative physical activity of patients with cancer is fragmented, and the synthetisation of this information will reveal facilitating and hindering factors that can be used to promote the achievement of physical activity recommendations.

Previously, several reviews of quantitative studies, most of which used meta-analysis, have been published on the health and well-being benefits of preoperative physical activity in patients with various cancers [9–17]. Additionally, one thematic synthesis has explored the experiences of patients with cancer and healthcare providers on prehabilitation [18]. The reviews of quantitative studies have demonstrated that preoperative physical activity can enhance patients’ physical health [9–12, 15], quality of life [12, 13] and physical recovery from cancer surgery [10–17]. In the review by Shen et al. [18], the aim was to explore the experiences of patients with cancer with the barriers to and facilitators of prehabilitation. The study revealed that prehabilitation can be supported through individualised approaches, social support and healthcare professionals’ engagement, while being hindered by the lack of motivation and limited physical opportunities [18]. However, the review lacked information on how patients with cancer describe their preoperative physical activity and excluded patients who engaged in unsupervised preoperative physical activity independently. The review also investigated the attitudes and perceptions of healthcare providers [18]. Therefore, there is a need for a review that specifically focuses on the experiences of patients with cancer with preoperative physical activity, while also taking into account the experiences of those patients with cancer who do not have access to prehabilitation programs.

Using a qualitative systematic review, this study set out to understand the personal experiences of preoperative physical activity in patients with cancer. The research questions for this review are as follows: (1) What kind of preoperative physical activity do patients with cancer engage in? (2) How do patients with cancer describe the facilitators of preoperative physical activity? (3) How do patients with cancer describe the barriers to preoperative physical activity?

2. Methods

The qualitative systematic review was chosen as the method for this study because of a desire to comprehensively synthesise the individual experiences and perceptions of patients with cancer regarding preoperative physical activity [19]. A Guide to Writing a Qualitative Systematic Review Protocol to Enhance Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing and Health Care by Butler et al. [19] was used as the methodological guideline for this review.

2.1. Search Strategy and Study Selection

A search was conducted using four databases (CINAHL, MEDLINE, Scopus and PsycINFO) in February 2025. Search terms and databases were identified in consultation with an academic health science librarian. Free-text words related to cancer, surgery, physical activity, qualitative and mixed methods and their synonyms, with the Boolean operators OR and AND, in addition to equivalent MeSH headings, were used in each database [19]. Physical activity was defined to refer to work and leisure-time physical activity and exercise [4]. The studies were required to be original peer-reviewed articles. In the Scopus database, the search was limited to titles, abstracts and keywords. The search strategies for the databases are shown in Online Resource 1, which is in the Supporting Information (available here).

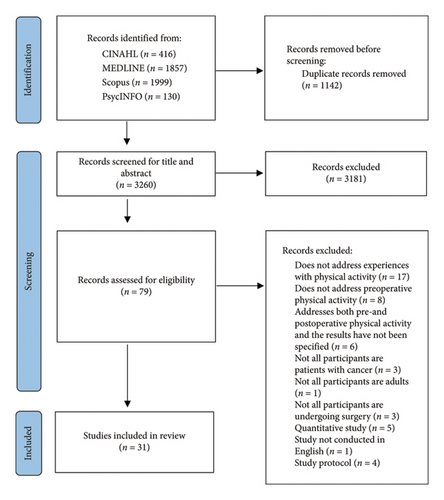

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) The study participants were adult patients with cancer, (2) the study dealt with preoperative physical activity, either through participation in a preoperative physical activity program or engagement in unsupervised preoperative physical activity independently, (3) the subject was addressed from the perspective of patients with cancer, (4) the study was a qualitative or a mixed-methods study with a distinct qualitative component, and (5) the study was empirical and peer-reviewed. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) The study was a literature review, and (2) the study did not contain empirical data. In total, 4402 studies were identified through database searching (Figure 1). Firstly, the duplicates were removed (n = 1142). Secondly, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the studies were screened for titles and abstracts (n = 3260) and full texts (n = 79) [19]. The search was otherwise conducted by one author (EN), but full-text studies were screened by two authors (EN and EHar). Ultimately, 31 studies were selected for analysis.

2.2. Critical Appraisal

The appraisal was conducted using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research (Table 1) [21]. The methodological quality of the studies was first appraised independently by two authors (EN and EHar), and secondly, appraisals were discussed until a consensus was reached [21]. The critical appraisal demonstrated that in most studies, the researcher’s cultural and theoretical location [23, 25–33, 36, 38, 41, 43–52] or philosophical perspective was not stated [22, 23, 25, 28–30, 34, 36–39, 41–45, 47–50, 52]. The researcher’s influence on the research was not described in six studies [31, 32, 36, 39, 43, 44]. Two studies did not mention the ethical principles of the study [26, 43], and one study lacked information on ethical approval [31]. Furthermore, in one study, the data were not analysed and represented congruently with the research methodology [47].

Authors Year of publication Country |

Purposes | Study design | Participants | Methods for data collection and analysis | Critical appraisal [21] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agasi-Idenburg et al. 2020. The Netherlands [22]. | To examine the experiences of older colorectal patients with cancer scheduled for surgery with the facilitators of, barriers to and preferences for preoperative exercise programs. | Qualitative research method. | Patients (n = 15), informal care givers (n = 13) and healthcare providers (n = 9). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: 72.7 ± 4.39 (range: not reported). Patients’ sex (female/male): 4/11. |

|

9/10 |

| Banerjee et al. 2021. United Kingdom [23]. | To investigate perspectives of preoperative vigorous-intensity aerobic interval exercise in patients with bladder cancer undergoing surgery. | Qualitative research method. | Patients (n = 14). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: 72.3 ± 6.0 (range: 64–82). Patients’ sex (female/male): 1/13. | Focus group interviews. Framework analysis. | 8/10 |

| Barnes et al. 2023. Canada [24]. | To examine the facilitators of and barriers to exercise prehabilitation in older adults with frailty scheduled for intra-abdominal or intrathoracic cancer surgery. | Qualitative research method. | Patients (n = 15). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: 72, SD not reported (range: 60–85). Patients’ sex (female/male): 8/7. |

|

10/10 |

| Beck et al. 2021. Denmark [25]. | To examine experiences with home-based preoperative multimodal recommendations in patients with colorectal or ovarian cancer scheduled for major abdominal surgery. | Mixed-methods research method. | Qualitative component: Patients (n = 5). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: 54, SD not reported (range: 51–65). Patients’ sex (female/male): 3/2. |

|

8/10 |

| Beck et al. 2021. Denmark [26]. | To investigate perspectives on prehabilitation in patients with colorectal or ovarian cancer undergoing major abdominal surgery. | Mixed-methods research method. | Qualitative component: Patients (n = 31). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: 60, SD not reported (range: not reported). Patients’ sex (female/male): 19/12. |

|

8/10 |

| Beck et al. 2022. Denmark [27]. | To examine prehabilitation-related experiences, thoughts and feelings in patients with colorectal or ovarian cancer scheduled for major abdominal surgery. | Qualitative research method. | Patients (n = 16). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: 58, SD not reported (range: not reported). Patients’ sex (female/male): 11/5. |

|

9/10 |

| Blomquist et al. 2023. Sweden [28]. | To investigate patients’ living habits before gastrointestinal cancer surgery. | Qualitative research method. | Patients (n = 6). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: 67.7, SD not reported (range: 51–78). Patients’ sex (female/male): 3/3. |

|

8/10 |

| Brahmbhatt et al. 2020. Canada [29]. | To investigate the feasibility and potential benefits of a home-based prehabilitation intervention in patients with breast cancer undergoing surgery. | Mixed-methods research method. | Qualitative component: Patients (n = 5) and healthcare providers (n = 2). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: not reported. Patients’ sex (female/male): not reported. |

|

8/10 |

| Brahmbhatt et al. 2024. Canada [30]. | To understand the acceptability of and experiences related to prehabilitation during neoadjuvant chemotherapy for women with breast cancer. | Mixed-methods research method. | Qualitative component: Patients (n = 6). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: 55, SD not reported (range: 43–67). Patients’ sex (female/male): not reported. |

|

8/10 |

| Burke et al. 2013. United Kingdom [31]. | To explore perceptions of quality of life in patients with advanced rectal cancer during a presurgical exercise program. | Qualitative research method. | Patients (n = 10). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: 58.2 ± 7.7 (range: 45–74). Patients’ sex (female/male): 7/3. |

|

7/10 |

| Burke et al. 2015. United Kingdom [32]. | To investigate experiences of a presurgical exercise program in patients with advanced rectal cancer. | Qualitative research method. | Patients (n = 10). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: 58.2 ± 7.7 (range: 45–74). Patients’ sex (female/male): 7/3. |

|

8/10 |

| Casanovas-Álvarez et al. 2024. Spain [33]. | To explore the perceptions and experiences of patients with breast cancer regarding a prehabilitation program during neoadjuvant therapy. | Qualitative research method. |

|

|

9/10 |

| Cooper et al. 2022. United Kingdom [34] | To explore facilitators of and barriers to a home-based presurgical physical activity program during neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with esophagogastric cancer. | Qualitative research method. | Patients (n = 22). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: 67.3 ± 8.2 (range: not reported). Patients’ sex (female/male): 4/18. |

|

9/10 |

| Daun et al. 2022. Canada [35]. | To investigate the perspectives of patients with head and neck cancer and healthcare providers on adding exercise prehabilitation into standard surgical care pathway. | Qualitative research method. | Patients (n = 10) and healthcare providers (n = 10). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: 60.8 ± 8.5 (range: 44–71). Patients’ sex (female/male): 1/9. |

|

10/10 |

| Drummond et al. 2022. Canada [36]. | To explore the experiences of a multimodal tele-prehabilitation program in patients with cancer scheduled for thoracic and abdominal cancer resection surgery. | Mixed-methods research method. | Qualitative component: Patients (n = 8). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: not reported. Patients’ sex (female/male): not reported. |

|

7/10 |

| Eser et al. 2024. Switzerland [37]. | To investigate interest in and expectations from prehabilitation program in patients with lung cancer. | Qualitative research method. | Patients: (n = 22). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: 70.6 ± 16.6 (range not reported). Patients’ sex (female/male): 10/22. |

|

9/10 |

| Hirschhorn et al. 2013. Australia [38]. | To investigate barriers to and facilitators of preoperative pelvic floor muscle (PFMT) training from the perspectives of referrers to and providers of PFMT and patients with prostate cancer undergoing surgery. | Qualitative research method. | Referrers to PFMT (n = 11), providers of PFMT (n = 14) and patients (n = 13). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: not reported. Patients’ sex (female/male): 0/13. |

|

8/10 |

| Karlsson et al. 2020. Sweden [39]. | To examine attitudes towards and perceptions of preoperative physical activity in older patients with colorectal cancer scheduled for surgery. | Qualitative research method. | Patients (n = 17). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: 75, SD not reported (Range: 70–91). Patients’ sex (female/male): 8/9. |

|

8/10 |

| Loughney et al. 2021. Ireland [40]. | To investigate perceptions of well-being and quality of life in patients with prostate cancer undergoing surgery after participating preoperative exercise program. | Qualitative research method. | Patients (n = 11). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: 60 ± 7 (range: not reported). Patients’ sex (female/male): 0/11. |

|

10/10 |

| Mao et al. 2023. The United States [41]. | To investigate the suitability and acceptability of a virtual mind-body prehabilitation program for patients with thoracic cancer scheduled for surgery. | Mixed-methods research method. | Qualitative component: Patients (n = 45). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: not reported. Patients’ sex (female/male): not reported. |

|

8/10 |

| Nielsen et al. 2021. Sweden [42]. | To examine the experiences of surgery with patients with oesophageal cancer and their personal advice to future patients. | Qualitative research method. | Patients (n = 63). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: 68.3, SD not reported (range: not reported). Patients’ sex (female/male): 18/45. |

|

9/10 |

| Parker et al. 2019. The United States [43]. | To investigate supports and barriers to home-based preoperative physical activity in patients with pancreatic cancer undergoing surgery during preoperative treatment. | Mixed-methods research method. | Qualitative component: Patients (n = 10). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: not reported. Patients’ sex (female/male): not reported. |

|

6/10 |

| Parraguez et al. 2023. Chile [44]. | To describe the perspectives and satisfaction of patients with colon, rectal or gastric cancer with tele-prehabilitation program. | Mixed-methods research method. | Qualitative component: Patients (n = 33). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: not reported. Patients’ sex (female/male): not reported. |

|

7/10 |

| Paulo et al. 2023. The United States [45]. | To examine barriers to and facilitators of physical activity prehabilitation in patients with kidney cancer undergoing surgery. | Qualitative research method. | Patients (n = 20), patients’ age (yr) ± SD: 62, SD not reported (range: 23–81). Patients’ sex (female/male): 8/12. |

|

8/10 |

| Pedersen et al. 2025. Denmark [46]. | To investigate the experiences of patients with prostate cancer participating in a multimodal prehabilitation program before radical prostatectomy. | Qualitative research method. | Patients (n = 8). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: not reported. Patients’ sex (female/male): 0/8. |

|

9/10 |

| Polen-De et al. 2021. The United States [47]. | To explore barriers to and facilitators of prehabilitation in patients with advanced ovarian cancer scheduled for surgery during preoperative treatment. | Qualitative research method. | Patients (n = 15). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: 64.3, SD not reported (range: not reported). Patients’ sex (female/male): 15/0. |

|

7/10 |

| Powell et al. 2023. United Kingdom [48] | To investigate how patients with colon, lung or esophagogastric cancer from diverse socioeconomic status groups perceived a prehabilitation and recovery program. | Qualitative research method. | Patients (n = 18) and clinician participants (nurses, doctors and other staff roles) (n = 24). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: 68.5, SD not reported (range: 40–80). Patients’ sex (female/male): 9/9. |

|

8/10 |

| Rammant et al. 2019. Belgium [49]. | To investigate the determinants of physical activity in patients with bladder cancer before and after surgery. | Qualitative research method. | Patients (n = 30). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: 72, SD not reported (range: 52–85). Patients’ sex (female/male): 8/22. |

|

8/10 |

| Smyth et al. 2024. Ireland [50]. | To explore the acceptability of exercise prehabilitation before breast, lung, uterine, prostate, liver, kidney or pancreatic cancer surgery among patients, family members and healthcare providers. | Mixed-methods research method. | Qualitative component: Patients (n = 12), healthcare professionals (n = 14) and family members (n = 5). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: not reported. Patients’ sex (female/male): not reported. |

|

8/10 |

| van der Zanden et al. 2021. The Netherlands [51]. | To explore possible content and indications for and barriers to prehabilitation in older adults undergoing oncologic gynaecologic surgery. | Qualitative research method. | Patients (n = 16) and healthcare professionals (n = 20). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: 70, SD not reported (range: 62–85). Patients’ sex (female/male): 16/0. |

|

9/10 |

| Wu et al. 2022. United Kingdom [52]. | To investigate the experiences and perceptions of patients with colorectal, breast or urological cancer with tele-prehabilitation | Qualitative research method. | Patients (n = 22). Patients’ age (yr) ± SD: 66, SD not reported (range: 42–83). Patients’ sex (female/male): 11/11. | Semistructured interviews. Deductive content analysis and Braun and Clarke method for thematic analysis. | 8/10 |

2.3. Data Analysis

The data were subjected to inductive content analysis. The analysis began by carefully exploring the data by reading the selected studies several times to obtain an overview of these data. Following this, the three research questions were analysed separately. The units of analysis consisted of words, parts of sentences and sentences describing the experiences of patients with cancer. Each study’s sentences related to the research questions were extracted, and data were reduced to open codes. Subsequently, based on similarities in content, the open codes were grouped into subcategories and named descriptively. In the next step, the subcategories were grouped into categories and named descriptively. The selected studies were reread several times during the analysis to avoid incorrect subjective interpretations [53]. The data were analysed by three authors (EN, EHar and EHaa). The authors discussed divergent perspectives during the analysis until a consensus was reached.

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Studies

The included studies (n = 31) were published from 2013 to 2025 and conducted in the United Kingdom [23, 31, 32, 34, 48, 52] (n = 6), the United States [41, 43, 45, 47] (n = 4), Denmark [25–27, 46] (n = 4), Sweden [28, 39, 42] (n = 3), Canada [24, 29, 30, 35, 36] (n = 5), the Netherlands [22, 51] (n = 2), Ireland [40, 50] (n = 2), Australia [38] (n = 1), Belgium [49] (n = 1), Switzerland [37] (n = 1), Spain [33] (n = 1) and Chile [44] (n = 1). The majority (n = 22) of studies were qualitative [22–24, 27, 28, 31–35, 37–40, 42, 45–49, 51, 52], and nine were mixed-methods studies [25, 26, 29, 30, 36, 41, 43, 44, 50]. The sample size of the studies ranged between 5 and 63. The participants presented with various types of cancer, including colorectal cancer [22, 39] (n = 2), rectal cancer [31, 32] (n = 2), breast cancer [29, 30, 33] (n = 3), ovarian cancer [47] (n = 1), gynaecological cancer [51] (n = 1), prostate cancer [38, 40, 46] (n = 3), bladder cancer [23, 49] (n = 2), gastrointestinal cancer [28] (n = 1), pancreatic cancer [43] (n = 1), kidney cancer [45] (n = 1), esophagogastric cancer [34, 42] (n = 2), head and neck cancer [35] (n = 1), thoracic cancer [41] (n = 1), lung cancer [37] (n = 1), colorectal or ovarian cancer [25–27] (n = 3), intra-abdominal or intrathoracic cancer [24, 36] (n = 2), colon, rectal or gastric cancer [44] (n = 1), colon, lung or esophagogastric cancer [48] (n = 1), colorectal, breast or urological cancer [52] (n = 1) or breast, lung, uterine, prostate, liver, kidney or pancreatic cancer [50] (n = 1). Patients’ median age ranged between 50 and 75. Methods of data collection and analysis varied between the studies (Table 1).

3.2. Preoperative Physical Activity in Patients With Cancer

The preoperative physical activity of patients with cancer was described in 20 studies selected for the review [23–34, 36, 40, 41, 43, 44, 46–48]. Patients participated in a supervised exercise program [23, 31–33] (n = 4), a supervised tele-prehabilitation program [44] (n = 1) or a home-based exercise training program [24–27, 29, 30, 34, 36, 41, 43, 46] (n = 11); participated in either a supervised centre-based or home-based exercise program [40, 48] (n = 2); or exercised unsupervised on their own [28, 47] (n = 2). In nearly all studies, patients’ preoperative physical training included aerobic activities [23, 24, 26, 28–34, 36, 40, 41, 43, 44, 46, 47] (n = 17). In most studies, patients’ physical training incorporated muscle-strengthening activities [24, 28–30, 33, 34, 36, 40, 41, 43, 44, 46, 47] (n = 13), and in some studies, stretching and mobility activities were also included [24, 29, 33, 41, 44, 47] (n = 6). There were many variations in the physical exercises performed, the duration of each exercise, the number of exercises performed per week, the total duration of physical training and physical training adherence (Table 2).

Author Year of publication Country |

Physical activity guidance | Physical activity included aerobic activity | Physical activity included muscle-strengthening activities | Physical activity included stretching and mobility activities | The physical exercises performed | The duration of each exercise | The number of exercises performed per week | The total duration of physical training | Physical training adherence | Cancer type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banerjee et al. 2021. United Kingdom [23]. | Patients participated in a supervised exercise group. | Yes. | No. | No. | • Vigorous-intensity interval exercise on a cycle ergometer. | ∼1 h. | Patients were instructed to exercise two times a week. | Not reported. | Not reported. | Bladder cancer. |

| Barnes et al. 2023. Canada [24]. | Patients participated in a home-based exercise training program. | Yes. | Yes. | Yes. |

|

1 h. | Patients were instructed to exercise three times a week. | Patients exercised for at least 3 weeks and an average of 5 weeks. | Physical activity adherence exceeded 75% in over 80% of the patients. | Intra-abdominal or intrathoracic cancer. |

| Beck et al. 2021. Denmark [25]. | Patients followed home-based exercise recommendations. | Not reported. | Not reported. | Not reported. | Not reported. | Not reported. | Patients were instructed to exercise every day. | The duration ranged from 1 to 18 days with an average of 12 days in patients with colorectal cancer and 9 days in patients with ovarian cancer. | Physical activity adherence exceeded 75% in over 50% of the patients. | Colorectal or ovarian cancer. |

| Beck et al. 2021. Denmark [26]. | Patients followed home-based exercise recommendations. | Yesa. | No. | No. |

|

Not reported. | Patients were instructed to exercise every day. | The duration ranged from 1 to 18 days. | Physical activity adherence exceeded 75% in over 50% of the patients. | Colorectal or ovarian cancer. |

| Beck et al. 2022. Denmark [27]. | Patients followed home-based exercise recommendations. | Not reported. | Not reported. | Not reported. | Not reported. | Not reported. | Patients were instructed to exercise every day. | The leaflet was handed to patients from 7 to 14 days before surgery. | Not reported. | Colorectal or ovarian cancer. |

| Blomquist et al. 2023. Sweden [28]. | Patients exercised unsupervised on their own. | Yesa. | Yesa. | No. |

|

Not reported. | Patients considered themselves as active, but the amount of exercise varied. | Not reported (patients exercised on their own). | Not reported. | Gastrointestinal cancer. |

| Brahmbhatt et al. 2020. Canada [29]. | Patients followed home-based exercise prescriptions. | Yes. | Yes. | Yes. |

|

The duration of aerobic exercises was 30–40 min. The duration of muscle-strengthening, stretching and mobility exercises is not reported. | Patients were instructed to perform aerobic exercises 3 to 5 days a week and resistance training 2 to 3 days a week. The number of stretching and mobility exercises is not reported. | Not reported. | Physical activity adherence exceeded 70% in 76% of the patients. | Breast cancer. |

| Brahmbhatt et al. 2024. Canada [30] | Patients followed home-based exercise prescriptions. | Yes. | Yes. | No. |

|

The duration of aerobic exercises was 30–40 min. The duration of muscle-strengthening exercises is not reported. | Patients were instructed to perform four to five training sessions per week of aerobic and resistance training. | Not reported. | 14% of patients were nonadherent to aerobic exercise and 41% to resistance training. | Breast cancer. |

| Burke et al. 2013. United Kingdom [31]. | Patients participated in a supervised exercise training program. | Yes. | No. | No. | • Interval exercise training on a cycle ergometer. | 30 min in the first week of training and 40 min after the first week. | Patients were instructed to exercise three times a week. | 6 weeks. | Physical training adherence was 98%. | Rectal cancer. |

| Burke et al. 2015. United Kingdom [32]. | Patients participated in a supervised exercise training program. | Yes. | No. | No. | • Interval exercise training on a cycle ergometer. | 30 min in the first week of training and 40 min after the first week. | Patients were instructed to exercise three times a week. | 6 weeks. | Not reported. | Rectal cancer. |

| Casanovas-Álvarez et al. 2024. Spain [33]. | Patients participated in a supervised exercise group. | Yes. | Yes. | Yes. |

|

The duration of an exercise session was 75 min. | Patients were instructed to exercise two times a week. | Patients exercised for 6 to 9 weeks, depending on their surgery date. | Not reported. | Breast cancer. |

| Cooper et al. 2022. United Kingdom [34]. | Patients participated in a home-based physical activity program. | Yes. | Yes. | No. |

|

The duration of aerobic exercises was 30 min. The duration of strengthening exercises is not reported. | Patients were instructed to exercise every day. | Not reported. | Not reported. | Esophagogastric cancer. |

| Drummond et al. 2022. Canada [36]. | Patients participated in a home-based exercise program. | Yes. | Yes. | No. |

|

The duration of aerobic and strength-training exercises was individually tailored. | The frequency of aerobic exercises was individually tailored. Patients were instructed to perform strength-training exercises two times a week. | Duration ranged from 2 to 15 weeks. | Not reported. | Thoracic and abdominal cancer. |

| Loughney et al. 2021. Ireland [50]. | Patients participated in either a supervised centre-based or home-based exercise program. | Yes. | Yes. | No. |

|

The duration of an exercise session was 40–60 min. (interval: 30–40, high interval: 17.5 and resistance training: 20 min). | If surgery was scheduled in 2 weeks, patients were instructed to exercise five times a week and if for later, three times a week. | Patients exercised an average of 4 weeks. | Physical training adherence was 84% in centre-based exercise program and 100% in home-based exercise program. | Prostate cancer. |

| Mao et al. 2023. The United States [41]. | Patients participated in a home-based mind–body fitness program. | Yes. | Yes. | Yes. |

|

45 min. | The program offered two exercise classes per week. Patients were encouraged to take part in more than one class. | Patients were referred at least 1 week before surgery. | Participation rate was 76% and 71% attended at least one class. | Thoracic cancer. |

| Parker et al. 2019. The United States [43]. | Patients followed home-based exercise prescriptions. | Yes. | Yes. | No. |

|

The duration of aerobic exercise was more than 20 min and the duration of body strengthening exercise was 30 min. | Patients were instructed to perform aerobic exercises three times a week and full-body strengthening exercises two times a week. | Patients exercised an average of 16 weeks. | Not reported. | Pancreatic cancer. |

| Parraguez et al. 2023. Chile [44]. | Patients participated in a supervised tele-prehabilitation program. | Yes. | Yes. | Yes. |

|

The duration of an exercise session was 45 min. | Patients were instructed to exercise two to three times a week. | The program consisted of eight exercise sessions. | The retention rate of the program was 46.7%. | Colon, rectal or gastric cancer. |

| Pedersen et al. 2025. Denmark [46]. | Patients participated in a home-based exercise program. | Yes. | Yes. | No. |

|

The duration of a cardio exercise session was 30 min, and the duration of a resistance exercise session was 20 min. | Patients were instructed to perform cardio exercise twice a week, resistance exercise three times a week and pelvic floor exercise daily. | 4 weeks. | Not reported. | Prostate cancer. |

| Polen-De et al. 2021. The United States [47]. | Patients exercised unsupervised on their own. | Yesa. | Yesa. | Yesa. |

|

Not reported. | The amount of exercise was small. | Not reported (patients exercised on their own). | Not reported. | Ovarian cancer. |

| Powell et al. 2023. United Kingdom [48]. | Patients participated in either a supervised centre-based or home-based exercise program. | Not reported. | Not reported. | Not reported. | Not reported. | Not reported. | Patients were instructed to exercise three times a week. | Not reported. | Not reported. | Colon, lung or eso-phagogastric cancer. |

- aSome of the patients.

3.3. Facilitators of Preoperative Physical Activity in Patients With Cancer

The facilitators of preoperative physical activity in patients with cancer were described in all 31 studies selected for the review [22–52]. Physical activity was facilitated by the experience of increased well-being, the experience of improved coping with cancer, the experience of the importance of physical activity, social support and physical activity resources (Table 3).

| The category | The subcategory |

|---|---|

| The experience of increased well-being | Improved health [24, 28, 33, 35, 46, 47, 52] |

| The experience of improved coping with cancer | |

| Increased participation in cancer care [23, 27, 30, 31, 34, 43, 46, 51] | |

| Relief from cancer-related distress [23, 26, 28, 29, 31–34, 39, 40, 45, 49, 51] | |

| The experience of the importance of physical activity | A physical activity routine [22–27, 29, 32, 34, 39, 43, 45, 51] |

| Social support | Healthcare professionals’ support [22, 23, 27, 28, 30, 35, 38, 39, 43, 45–47, 50, 51] |

| Physical activity professionals’ support [22–27, 29, 30, 32–35, 37, 39–41, 44–46, 48, 50–52] | |

| Physical activity resources | |

3.3.1. The Experience of Increased Well-Being

Improved health represented an opportunity to improve general [24, 33, 35, 46, 47, 52] and mental health [28, 33, 35, 47]. Exercise prehabilitation resulted in enhanced health behaviour [29, 40] because it contributed to positive changes in exercise [40], lifestyle choices [30, 35, 40], diet and alcohol consumption [40]. Also, cancer diagnosis increased patients’ motivation to engage in lifestyle change [52]. The development of physical performance included the development of physical fitness [23, 36, 46] and strength [23, 28, 41]; muscle gain [31, 49]; better control of the pelvic floor muscles; less stiffness [49]; and improved mobility [35]. Additionally, exercise enhanced patients’ functional abilities in activities of daily living [31], increased their activity levels [31, 32] and helped them manage preoperative physical challenges [45]. Objective measures of physical fitness development [23] and observing improvement [24, 51] promoted patients’ preoperative physical activity.

Increased meaningfulness of life consisted of a range of benefits achieved through preoperative physical activity, such as increased quality of life [40, 52], vitality [31], energy levels [28, 49], relaxation, satisfaction [49], enjoyment [24], hopefulness [40] and feelings of normalcy [31]. Physical activity also cultivated a more positive attitude [31, 40]; made patients feel better [28, 49, 51], stronger [33] and more secure [46]; reduced their boredom; and helped clear their heads [49]. Furthermore, preoperative physical activity provided patients with a sense of structure [31, 32]; allowed them to do something meaningful [34, 39]; and allowed them to obtain a sense of control [29, 31, 46], clarity [46], direction and purpose [31, 32].

3.3.2. The Experience of Improved Coping With Cancer

Relief from the physical symptoms of cancer included relief from fatigue [31, 33, 36], pain, nausea [36] and loss of muscle mass [33]. In addition, physical activity improved patients’ sleep [23, 49]. Enhanced cancer survival represented an opportunity to improve cancer treatment, outcome, prognosis [47], survival [35, 42, 52] and postoperative independence [39], as well as to facilitate recovery [23, 26, 29, 34, 35, 39, 42, 43, 48–52]. Preoperative physical activity was also motivated by concerns about the well-being of patients’ children and partners after these patients’ potential deaths [49]. Patients wanted to be in good physical shape for the surgery [33, 39, 51], and physical activity enhanced preparation for the operation, both physically [23, 35, 40, 42, 46] and mentally [23, 40, 46]. Additionally, in performing preoperative physical activity, patients wanted to improve their recoveries [23, 35, 45, 46, 49], surgical outcomes [23, 24, 31, 38, 47] and chances of surviving the surgery [34] and reduce the length of their hospital stays after operation [27, 34, 36].

Patients experienced increased participation in cancer care when as a consequence of preoperative physical activity, they played a more active role [23, 31, 34, 46, 51], took action [27], took on responsibility [43, 51] and took control over their health and treatment [30, 34]. Preoperative physical activity gave relief from cancer-related distress in various ways. The unwillingness to accept a cancer diagnosis and the fear of being stigmatised as a sick person encouraged patients to remain physically active [49]. Furthermore, preoperative physical activity provided relief from the illness [31]; facilitated adjustment to the situation [28]; helped to control stress [40] and mental challenges [45] after the cancer diagnosis; and provided a distraction from [26, 31, 34, 40, 51] and the release of [32, 39] cancer- and surgery-related worries, as well as offering a chance to participate in a positive [23, 29, 31, 32] and enriching [33] activity.

3.3.3. The Experience of the Importance of Physical Activity

The experience of the importance of physical activity facilitated preoperative physical activity [51]. A physical activity routine was created based on the past experiences of exercise [22–24, 43], a previous active lifestyle [22, 39, 45] and participation in a preoperative physical activity program [32]. Engagement in a physical activity program also encouraged patients to increase their exercise levels outside the program [32, 34]. In addition, the structure of exercise prescription [24, 29] and tracking adherence [25–27, 34, 45, 51] and intensity [23] promoted regular physical activity. Understanding the significance of physical activity facilitated patients’ preoperative physical activity [22]. Knowledge about the health benefits of preoperative physical activity inspired patients to exercise [23], and patients were able to increase this knowledge through an exercise program [40, 41, 52]. Furthermore, the positive effects of exercise previously experienced by patients [22, 39] and an understanding of the risks of being inactive before surgery [38, 39] promoted patients’ preoperative physical activity. A positive attitude towards physical activity included positive expectations regarding physical activity [45, 48, 49, 52]. Patients with confidence in their abilities were positive about physical activity [39] and participation in an exercise program increased this confidence [41].

3.3.4. Social Support

Participation in a preoperative physical activity program allowed patients to seek social support [31]. Healthcare professionals’ support enhanced patients’ motivation to engage in physical activity [23, 27, 28, 30, 45–47], and it consisted of theoretical and practical knowledge [39], guidance [50], recommendations [23, 38, 46, 47], encouragement [22, 35, 39, 43] and monitoring [39] concerning preoperative physical activity. Patients appreciated the support received from both physicians [22, 35, 38, 43] and nurses [51]. Physical activity professionals’ support facilitated patients’ preoperative physical activity [23], because it allowed patients to feel more comfortable [29], safe and cared for [32, 33]. It also provided them with encouragement [32], insight [29] and feedback on performance [32] and progress [32, 33, 52]. The support included practical advice [40], instructions [24, 29, 39], guidance [39] and supervision [33]. Patients’ preoperative physical activity could be supported by the individualisation of physical activity programs [24, 29, 33, 35, 41, 46, 48, 51, 52], in other words, by suiting the programs to patients’ personal physical [26, 33] and mental [33] conditions, activity levels [25, 29], abilities [24, 33], needs [22, 24, 25, 50], goals [24, 34, 51, 52] and possibilities [22]; appropriate difficulty levels [22, 24, 33, 51]; and everyday lives [25, 26]. Designing a physical activity program should also reflect patients’ individual preferences [22, 24–26, 35, 37]. Some patients, for example, wanted to participate in a home-based physical activity program [22, 24, 26, 27, 29, 30, 34, 37, 44, 46, 51, 52], and others wanted to participate in a facility-based physical activity program [22, 26, 27, 29, 37, 45]. Furthermore, some patients desired a structured exercise program, and others desired less formal movement recommendations [35]. Patients participating in home-based programs appreciated the possibility of remote support [37, 40], such as support received via phone calls [24, 29, 30, 34, 37, 44, 51, 52].

By participating in an exercise program, patients were able to receive peer support, which facilitated their preoperative physical activity [22, 31, 33, 34, 37]. This support appeared in various forms, as it allowed patients to increase their social contacts [31, 52]; complete exercises with another person [24, 32, 51]; share experiences [23, 31–34, 38, 40, 52]; encourage [23, 34] and empathise [33] one another; enjoy exercising more [31, 32]; and find meaning [31], companionship [32, 40], connectedness [32, 40, 41] and comfort [41]. Loved ones’ support enhanced patients’ preoperative physical activity and included support from family [23, 24, 27, 30, 34, 37–39, 43, 51, 52] and friends [24, 30, 34, 39, 43, 51, 52], encouragement [49, 52] and compliments [49] from family and friends and the participation of family and friends in physical activity [45, 49].

3.3.5. Physical activity Resources

The patients needed to reserve time for physical activity [33, 39, 46]. The patients appreciated the opportunity to reschedule the day or time of their exercises if applicable [32, 46]. Physical environment resources included neighbourhood physical activity resources [33, 43] and walkability [43] and tools with which to perform exercises [33, 39], such as resistance bands [29].

3.4. Barriers to Preoperative Physical Activity in Patients With Cancer

The barriers to preoperative physical activity in patients with cancer were described in 23 studies [22–24, 26–31, 33–36, 38, 39, 43, 45, 47–52] selected for the review. Physical activity was prevented by health limitations, inadequate knowledge about physical activity, a negative attitude towards physical activity and inadequate physical activity resources (Table 4).

| The category | The subcategory |

|---|---|

| Health limitations | Cancer-related health limitations [22, 24, 26–28, 31, 39, 45, 47, 49, 51] |

| Inadequate knowledge about physical activity | Insufficient information on recommendations for physical activity [33, 35, 38, 39, 52] |

| Insufficient information on the importance of physical activity [22, 33, 35, 38] | |

| A negative attitude towards physical activity | |

| Inadequate physical activity resources | Insufficient healthcare resources [38, 39] |

| A lack of time being reserved for physical activity [22, 26, 27, 29, 30, 38, 39, 43, 45, 47–49, 51] | |

| Financial costs [38, 47] | |

3.4.1. Health Limitations

Cancer-related health limitations included physical symptoms [22, 26–28, 39, 47], such as fatigue [22, 24, 31, 45, 47], pain [31, 45], abdominal pain and distension [47], loss of appetite [45], difficulty breathing [47], faecal [22] and urinary [49] incontinence and haematuria [45]. Furthermore, poor mental health during the preoperative period, including anxiety, depression [45] and mental stress [45, 51] restricted patients’ preoperative physical activity. Cancer treatment-related health limitations prevented patients’ preoperative physical activity [28, 30, 43], and these limitations manifested as physical symptoms [22, 39, 47], such as muscle, hand [45], foot [45, 47] and bone [47] pain; nausea [45] and neuropathy limiting mobility [47]. Additionally, chemotherapy-related symptoms limited patients’ preoperative physical activity [34, 47, 50] because the patients felt sick [49] and suffered from decreased immune system function [33], fatigue [30, 33, 47, 49], pain [33, 49], weakness, dizziness, neuropathies [33], nausea [47], loss of appetite and weight loss [49]. Non-cancer–related health limitations included poor physical condition [51]; fatigue [28] and medical comorbidities [22, 39], such as haemodialysis [45], heart disease [28, 45], recent surgeries [45], musculoskeletal conditions [24, 28, 49], fractures [49], arthritis [34], depression [28], anxiety [27] and severe difficulties with memory [28]. Furthermore, being dependent on care made it more difficult for patients to participate in physical activity programs [51].

3.4.2. Inadequate Knowledge About Physical Activity

Patients had insufficient information on recommendations for physical activity [35] and available prehabilitation programs [33, 52]. This shortage of information was due to a lack of communication from healthcare professionals related to preoperative physical activity [38, 39]. Furthermore, too-general and nonspecific exercise information limited patients’ preoperative physical activity [39]. Insufficient information on the importance of physical activity was apparent when patients had not been informed about the benefits of preoperative physical activity [33, 35, 38] and the importance of being in good physical condition before surgery [22].

3.4.3. A Negative Attitude Towards Physical Activity

Questioning the importance of physical activity involved doubting the meaning [38], benefits [48, 49] and outcomes [39, 49] of preoperative physical activity and the effectiveness of a short preoperative physical activity program [39, 45]. After a cancer diagnosis, physical activity [28, 49] and the potential side effects of surgery [38] felt irrelevant to some patients, the urgency of the surgery caused patients to underestimate the importance of optimisation and patients felt they should conserve their energy for the postoperative period [39]. Furthermore, previous positive experiences with surgery and recovery from it led patients to feel ready for the operation without any additional effort [39, 48]. A lack of interest in physical activity manifested as a lack of motivation [29, 51] and desire [49], as well as an experience of laziness [39, 49], being overwhelmed after cancer diagnosis [30, 48], difficulty in starting physical activity [49] and fixed patterns [51]. Negative experiences with physical activity [39], fitness devices [49] and unimproved fitness [23], as well as the negative experiences of peers [38], restricted patients’ preoperative physical activity. Cancer treatment [49], self-doubt [39] and aging-related limitations [39, 45, 49] caused patients to lack confidence in their physical abilities.

3.4.4. Inadequate Physical Activity Resources

Having insufficient healthcare resources restricted patients’ preoperative physical activity because they felt dependent on healthcare resources to facilitate physical activity [39]. In addition, patients with prostate cancer found it difficult to find healthcare professionals to provide pelvic floor muscle training without referrals from their surgeons [38]. A lack of time being reserved for physical activity limited patients’ preoperative physical activity [26, 38, 43, 45, 47], and this was due to other hospital appointments [22, 29, 30, 39, 45, 49], the short time frame before surgery [22, 39, 45, 48, 49, 51], professional [29, 45, 47] and personal [29, 45] responsibilities, social activities [27], practical tasks [27, 45] and life changes [39]. Having insufficient physical environment resources restricted patients’ preoperative physical activity and included limitations in the environment [39]; a lack of exercise facilities [33, 45], equipment and local access [47]; challenges related to exercise [23, 34] and technical equipment [36]; and bad weather [24, 29, 33, 34, 43, 45]. Physical activity was also restricted by logistical barriers [43], such as the need for travel [23, 38, 47, 51], a requirement to be in a certain place at a certain time [49]; and a need for parking [23]. Financial costs limited patients’ preoperative physical activity [38, 47].

4. Discussion

The purpose of this qualitative systematic review was to explore the experiences of patients with cancer with preoperative physical activity. Based on the results of this review, there is great variation in preoperative physical activity guidance, the content of physical activity, the physical exercises performed, and the amount and duration of physical training. Only a very limited number of studies [28, 47] (n = 2) have been conducted on the circumstances in which patients with cancer engaged in unsupervised preoperative physical activity independently. In the future, greater attention should be given to determining what constitutes a sufficient content and amount of physical activity when sharing information with patients diagnosed with cancer and designing preoperative physical activity programs to ensure that the activity is in line with recommendations set for patients with cancer [5]. Insufficient preoperative physical activity in patients with cancer has also been noted in prior studies [7, 8].

According to the results of this review, preoperative physical activity is facilitated by the experience of increased well-being, the experience of improved coping with cancer, the experience of the importance of physical activity, social support and physical activity resources. One important result of this review is that in addition to improved physical preparation for surgery, preoperative physical activity also enhanced patients’ mental preparation for surgery. This improvement in mental preparedness manifested in the management of stress and mental challenges, relief from worries and the provision of a positive distraction. Increased health and well-being due to physical activity in patients with cancer have also been identified in previous studies [9–17]. This review also deepened our understanding of patients’ perceptions of the individualisation of preoperative physical activity programs. Based on the results of this review, preoperative physical activity should be tailored to a patient’s physical and mental condition, activity level, abilities, needs, goals, possibilities, appropriate difficulty level, everyday life and preferences. Earlier literature reviews [18] have also recognised the importance of the individualisation of physical activity programs in patients with cancer. According to the results of this review, establishing a physical activity routine helped patients to remain physically active after cancer diagnosis. Given the prevalence of cancer [1], many individuals experience cancer during their lifetime. Therefore, it can be concluded that healthcare professionals should encourage all patients to engage in physical activity.

In accordance with the results of this review, preoperative physical activity is prevented by health limitations, inadequate knowledge about physical activity, a negative attitude towards physical activity and inadequate physical activity resources. An important result of this review is that some patients questioned the importance of preoperative physical activity and the effectiveness of a short physical activity program. The impact of the absence of information [6] and adequate facilities [18] on physical activity in patients with cancer also emerged in earlier studies. To increase the awareness of and motivation to engage in preoperative physical activity, patients should be better informed about its importance and benefits. Furthermore, physical activity resources should be provided through financial support for the most vulnerable patients, and digital physical activity guidance opportunities should be developed.

4.1. Study Limitations

This systematic qualitative review has some limitations. The findings of the review may be subject to distortion due to the fact that research data are predominantly derived from patients who participated in the studies, with only a few interviews conducted to ascertain the experiences of those who dropped out of the studies or refused to participate [48]. Almost all the included studies were conducted in Western countries, and one study had to be excluded because it was not written in English. The context should be considered when interpreting review findings because the experiences of other cultures may be under-represented. Furthermore, in the Scopus database, the search was limited to titles, abstracts and keywords to focus the search on the research questions, which may have affected the search results. Lastly, identifying appropriate research evidence was challenging for some studies selected for the review. Some studies explored the experiences of both pre- and postoperative physical activity [49], investigated preoperative physical activity from the perspective of healthcare professionals [22, 29, 35, 38, 48, 50, 51], informal caregivers [22] and family members [50] in addition to patients or explored the experiences of multimodal prehabilitation [24–27, 30, 36, 37, 44, 46, 52]. Special accuracy was ensured during the data-extraction phase so that all research evidence that did not clearly deal with the experiences of patients with cancer with preoperative physical activity was ignored.

5. Conclusion

Based on the results of this review, it can be concluded that healthcare professionals should discuss the physical activity tendencies and levels of patients diagnosed with cancer as part of cancer treatment. Patients should also be provided with information on the health and well-being benefits of preoperative physical activity and directed to either maintain or increase their physical activity levels before surgery. Furthermore, based on the experiences of patients with cancer, preoperative physical activity should also be enhanced by offering all patients with cancer the opportunity to participate in preoperative physical activity programs that consider their personal characteristics, preferences and available physical activity resources. In the future, more research should be conducted to examine the experiences of preoperative physical activity in patients with cancer who lack the opportunity or choose not to participate in prehabilitation programs.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Idea for the review: Essi Nikkinen, Eeva Harju, Elina Haavisto and Teemu Murtola.

Literature search: Essi Nikkinen and Eeva Harju.

Data analysis: Essi Nikkinen, Eeva Harju and Elina Haavisto.

First draft of the manuscript: Essi Nikkinen.

Critical revision: Eeva Harju, Elina Haavisto and Teemu Murtola.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any funds, grants, or other support during the preparation of this manuscript.

Supporting Information

Online Resource 1 presents the search strategies for the databases.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data analysed during the study are available from the corresponding author upon request.