Unmet Supportive Care Needs in Adults With Li–Fraumeni Syndrome: A Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

Introduction: Individuals with Li–Fraumeni syndrome (LFS) face an increased risk for multiple cancers. LFS is caused by pathogenic variants in the TP53 gene and individuals with LFS are recommended intense cancer surveillance programs to improve survival. Unmet supportive care needs (uSCN) are understudied for this rare condition. This study aims to investigate uSCN to draw implications for improving healthcare for individuals with LFS in Germany.

Methods: Using a mixed-methods approach, affected individuals completed the German version of the Supportive Care Needs Survey Short Form (SCNS-SF-34) and semistructured qualitative interviews. Participants were recruited through newsletters, social media, personal contact, and during routine surveillance appointments at University Hospital Heidelberg and Hannover Medical School between March 2020 and June 2021. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the quantitative data. The interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed via content analysis.

Results: Seventy individuals with LFS completed the survey, from which 20 have also participated in the qualitative interview. The highest number of unmet needs was indicated by the domain “psychological needs” (M = 36.90, SD = 28.91), followed by “information and health system needs” (M = 26.97, SD = 25.17). An unmet need in the domain “sexuality” was indicated by 25%–33% of participants. Interview analysis revealed four main need categories: psychological, health system and information, communication, and daily living.

Conclusion: Individuals with LFS reported primarily unmet psychological and informational needs. Unmet needs may dynamically change during the different trajectories of individuals with LFS (initial diagnosis, surveillance, cancer onset, and treatment). A regular assessment and increased awareness for uSCN would be beneficial for addressing different needs at different time points.

1. Introduction

Li–Fraumeni syndrome (LFS) is an autosomal dominant inherited rare cancer predisposition syndrome (CPS) caused by (likely) pathogenic variants in the tumor suppressor gene TP53, with a highly elevated lifetime cancer risk for several tumors with a possible onset already in early childhood [1]. Approximately 16,000 people in Germany are estimated to be affected by this rare disease [2]. The syndrome is highly penetrant, as for example, 78% of the studied individuals with LFS developed at least one cancer, 43% even multiple malignancies within 20 years [3]. As there is no cure for the syndrome, intense tumor surveillance protocols and therefore early tumor detection have proven to increase the survival rate of these individuals: 100% 3-year overall survival in the surveillance group compared to 21% in the nonsurveillance group [1, 4]. However, surveillance includes multiple examinations per year (e.g., whole-body MRI) and causes, along with the devastating lifetime cancer risk, high levels of distress and impaired quality of life in individuals diagnosed with LFS [5] and partners [6].

Especially in rare and comparably understudied cancer populations, providing targeted healthcare is a pressing issue [7, 8]. Exploring unmet supportive care needs (uSCN) is essential for evaluating, redesigning and providing healthcare regardless of acute cancer treatment or survivors [9]. Needs can be defined as “the requirement of some action or resource that is necessary, desirable, or useful to attain optimal well-being” [10]. For example, perceived unmet needs for information are associated with higher levels of anxiety and depression in cancer patients [11] and survivors [12] or affect general health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [12]. In particular, unmet psychological/emotional needs are important for cancer patients [13]. This can be found for different tumor stages, ages, or settings [13–15]. In addition, uSCN remain quite stable over time [15], even 10 years after the initial diagnosis [16]. In addition, culture-specific differences in uSCN exist [17], which are relevant for exploring the German population. USCN have been studied in several subcohorts of oncology in Germany, such as breast cancer [18] or in palliative cancer care [19].

However, to date, no data are available for uSCN of individuals with LFS. Therefore, this is the first study to explore uSCN in the context of LFS by combining a validated quantitative questionnaire and qualitative methods. This allows guidance for targeted clinical implications and interventions for this high-risk group in the German healthcare service.

2. Methods

2.1. Design and Participants

This study is part of the German ADDRess alliance (translational research for persons with Abnormal DNA Damage Response, supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research; https://www.krebs-praedisposition.de/en). Individuals (≥ 18 years) with LFS, regardless of the time point of their LFS diagnosis and current cancer situation, were eligible to participate as previously described [20]. We combined several recruitment strategies to reach individuals with this rare condition. We approached eligible individuals during their routine appointments at University Hospital Heidelberg and Hanover Medical School. We recruited participants from previous studies in which they had consented to being recontacted for future research. Furthermore, we provided information on the abovementioned ADDRess website, on LFS-related social media and via newsletters of the German LFS Association.

We collected quantitative (March 2020–June 2021) and qualitative data through 20 interviews (until October 2020). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Heidelberg (S-017/2020) and Hannover (7233) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2013).

2.2. Procedures and Measures

The Supportive Care Needs Survey Short Form (SCNS-SF-34) [21] measures the perceived need strength for 34 needs classified into five domains: physical and daily living (5 items), psychological (10 items), patient care and support (5 items), health system and information (11 items), and sexual (3 items) needs. Participants rated each of these needs for the previous month using a five-point Likert scale: (1) no need because not applicable, (2) no need because satisfied, (3) low need, (4) moderate need, and (5) high need. In addition, we used 15 investigator-designed items to assess sample characteristics on demographics and LFS-related variables (cancer history and estimated cancer risk).

We designed a semistructured interview script based on clinical experiences and a review of the current literature. The authors S.K. (PhD candidate/psychologist), I.M. (medical expert trained in internal medicine and psychosomatics and clinician scientist, full professor), J.R. (resident physician for internal medicine and psychosomatics, clinician scientist), S.S. (medical expert on LFS, gynecooncologist, clinician scientist, associate professor), and J.N. (board certified gynecologist, clinician scientist) were involved in the development of interview script. No other authors were involved in the development, conduction, or analysis of interviews. The interview script was not pilot-tested. However, we incorporated emerging new topics after conducting the first interviews, resulting in a second version of the interview script. This final script consisted of 56, mostly open-ended questions. The script explored participants’ experiences with and attitudes toward surveillance (number of questions: 10), psychosocial burdens and care (11), the internet and media (8), the health system (7), participatory decision-making, (4) and questions concerning issues in the social environment (family: 3; partner/friends: 10; career: 3).

After providing written informed consent, we scheduled interviews at the convenience of the participants. As authors S.S., I.M., and J.N potentially had contact with participants due to their clinical work, the author SK, who had previous experience in script-based interviews, conducted all but one via telephone. Participants were asked to be at home and able to speak without interruptions. Most interviews were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which limited access to clinical appointments and face-to-face interactions. Interviewees were in contact with the interviewer (SK) during recruitment and were informed about the study goals. The interviews were audio-recorded (Philips Digital Voice Tracker) and transcribed verbatim. No visual observations were assessed, no repeat interviews were carried out, and no field notes were taken. The transcripts were not returned to the participants, and they did not provide feedback on the findings.

2.3. Statistical Methods

2.3.1. Quantitative Analysis

We conducted descriptive analyses of sociodemographic, LFS-related, and SCNS-SF-34 data. Descriptive analysis was performed to identify patterns of high unmet needs among the five domains, which were transformed (range 0–100) to take different item numbers into account. We performed all analyses with SPSS. If individual items in a domain of the SCNS-SF-34 had missing values in less than or equal to 20%, these missing values were replaced by the mean of the nonmissing items on the respective domain for that patient (cases N = 8). Otherwise, we did not replace values, and the description of the measure was based on the complete case set of the respective scale. Three patients were excluded when calculating the sum scores of SCNS-SF-34 (N = 67), mainly because of missing data in the “sexuality” domain. In order to identify group differences considering the relationship status (single vs. relationship) and cancer history (no history of cancer vs. at least one cancer), we performed the nonparametrical Mann–Whitney U test, as it is robust and less sensitive to violations of test assumptions in small cohorts.

2.3.2. Qualitative Analysis

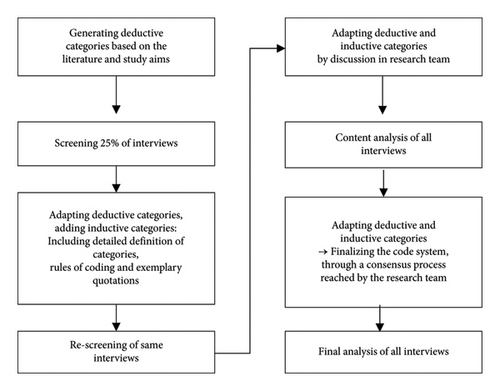

Qualitative content analysis of the transcribed interviews was performed based on the principles of inductive and deductive category development according to Mayring [22]. The combination of deductive and inductive categories is a recommended approach as it combines the advantages of both approaches, including reducing the risk of bias [23]. Sentences as well as whole paragraphs could be identified as a code. Deductive categories derived from previous research on uSCN were used for the first screening of transcribed interviews (e.g., “psychological needs” and “communication needs”). Afterward, inductive categories were derived from several analysis rounds of the interview material (see Figure 1). As themes were recurrent among different participants, they were compared and adapted until the relevant main themes for all participants could be defined. We did not assess intercoder reliability, but to ensure analysis quality, experienced researchers (S.K., I.M., and J.R.) discussed ambiguities and recoded transcripts until a consensus was reached about the code categories. Data were pseudonymized for analysis and consensus discussion. Data saturation was discussed among all the authors. The analysis process is shown in Figure 1, and the Standard for Reporting Qualitative Research (SPQR) checklist is provided in Supporting Information, Table A. We used the software MAXQDA.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

We present data from 70 study participants with LFS who took the SCNS-SF-34 and 20 interviews (Table 1). Both cohorts had a younger mean age (SCNS-SF-34: 41.53 years; interview: 36 years), were mostly female (SCNS-SF-34: 82.9%; interview: 85%), and were married or in a relationship (SCNS-SF-34: 74.3%; interview: 80%).

| Full cohort (N = 70) | Interviewees (N = 20) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M/SD | M/SD | |||

| Age (years) | 41.53 ± 12.11 | 39.45 ± 9.80 | ||

| N | N (%) | N | N (%) | |

| Female | 70 | 58 (82.9) | 20 | 17 (85) |

| Educational level | 69 | |||

| Basic school-leaving certificate | 8 (11.6) | 1 (5) | ||

| Tenth grade | 16 (23.2) | 6 (30) | ||

| Vocational school entrance | 7 (10.1) | 1 (5) | ||

| Twelfth/thirteenth grade | 9 (13.0) | 2 (10) | ||

| Bachelor’s, master’s, and doctorate | 24 (34.8) | 6 (30) | ||

| Other | 5 (7.2) | 4 (20) | ||

| Occupational status | 70 | |||

| Student/apprentice | 6 (8.6) | 1 (5) | ||

| Stay-at-home parent | 3 (4.3) | 1(5) | ||

| Employee or freelancer | 50 (71.4) | 13 (65) | ||

| Retired | 6 (8.6) | 2 (10) | ||

| Other | 5 (7.1) | 3(15) | ||

| Insurance status | 70 | |||

| Compulsory | 65 (92.9) | 19 (95) | ||

| Private | 5 (7.1) | 1 (5) | ||

| Marital status | 70 | |||

| Single | 14 (20.0) | 3 (15) | ||

| In a relationship | 11 (15.7) | 4 (20) | ||

| Married | 41 (58.6) | 12 (60) | ||

| Divorced/separated | 3 (4.3) | 1 (5) | ||

| Widowed | 1 (1.4) | — | ||

| Children | ||||

| Having children | 70 | 39 (55.7) | 9 (45) | |

| Child(ren) with cancer history | 39 | 9 (23.1) | 3 (15) | |

| Li–Fraumeni syndrome/cancer history | ||||

| Personal cancer history | 70 | 47 (67.1) | 17 (85) | |

| One or more siblings with a diagnosis of Li–Fraumeni syndrome | 58 | 27 (46.5) | 13 (68) | |

| Loss of parents through cancer | 68 | 13 (19.1) | 6 (30) | |

| Surveillance participation | 67 | |||

| Complete adherence to surveillance | 37 (55.2) | 11 (55) | ||

| No or partial adherence to surveillancea | 30 (44.8) | 9 (45) | ||

- aPartial adherence includes missing some recommended examinations or undergoing them not as often as recommended.

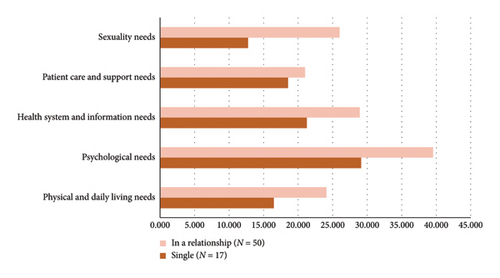

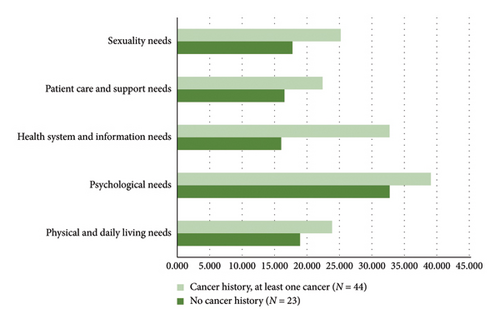

In Table 2, we present the 10 items most frequently identified as unmet needs in the SCNS-SF-34. Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the results differentiated according to relationship status and cancer history. A detailed insight into descriptive results on all SCNS-SF-34 items is provided in Supporting Information in Tables B and C. The interview duration ranged between 35 and 75 min, with 52 min on average. We identified four main topics (I-IV) with three or four subcategories each (Table 3). In line with our mixed-methods approach, we present quantitative and qualitative results jointly. The domains of SCNS-SF-34 and identified categories of content analysis were used to structure the mixed-methods data comprehensively.

| Rank | N (%) |

|---|---|

| 1. Uncertainty about the future (P) | 41 (58.6) |

| 2. Concerns about the worries of those close to you (P) | 37 (53.6) |

| 3. Learning to feel in control of your situation (P) | 36 (51.4) |

| 4. Feelings about death and dying (P) | 34 (48.6) |

| 5. Worry that the results of treatment are beyond your control (P) | 34 (48.6) |

| 6. Fears about the cancer spreading (P) | 33 (47.1) |

| 7. Lack of energy/tiredness (D) | 32 (45.7) |

| 8. Anxiety (P) | 28 (40.0) |

| 9. Being informed about cancer which is under control or receding (that is, remission) (H) | 28 (40.6) |

| 10. Having one member of hospital staff with whom you can talk to about all aspects of your condition, treatment, and follow-up (H) | 27 (39.1) |

| 11. Feelings of sadness (P) | 27 (38.6) |

| 12. Keeping a positive outlook (P) | 27 (38.6) |

- Note: (H) = health system and information needs; (D) = physical and daily living needs; (P) = psychological needs.

| Main category | Subcategory | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| I. Psychological needs | a. Cancer diagnosis | Interviewees describing the situation of having been diagnosed with cancer and its treatment | “So the first shock is of course the cancer diagnosis” |

| b. Family history and family planning | Hereditary aspects of LFS: Descriptions of how LFS influenced thoughts on one’s own family planning as well as past experiences with cancer in the family | “Do you want to have children or not? That is, I would say, perhaps also an inner conflict that you have there. Do you or don’t you” | |

| c. Fear of progression and worries regarding the future | Statements on anxiety fear and worries related to LFS and cancer | “And you know with LFS it can be over very quickly and I think I always have to live with that fear” | |

| II. Health system and information needs | d. Need for psychosocial support | Attitude toward and experience with psychosocial support | “No one had asked about that. And I already had a need to talk at that point. But there was just no one. So it just wasn’t suggested to me” |

| e. Gain of information and interest of care providers | Experiences of given information (or lack thereof) by healthcare providers/providing institutions | “So my family doctor, she’s completely out of the loop there” | |

| f. Desire for a central contact point and network | Experiences with healthcare providers with a special focus on how they should be organized and interact with each other | “It took me a long time to figure out where to go to” | |

| III. Communication needs | g. Physician communication | Examples and expectations on how doctors (should) communicate with interviewees | “And I always have to ask for the findings to be sent to me in writing, and that doesn’t always happen. So I always have to call and call after that. That is a bit difficult (…)” |

| h. To be taken seriously by care providers and be noticed as a person with LFS | Statements regarding the fact that interviewees experienced (not) being taken seriously by healthcare providers or how they wished they would be taken seriously | “And no doctor took that seriously. (…) That was the worst thing for me, that I always felt that I was talking to a wall” | |

| i. Impact of LFS diagnosis on partner communication | Interviewees describing their communication with their partner, how (much) it is influenced by LFS topics and how they wished communication to be | “But it is often an issue. Especially because of the children. It is often an issue” | |

| j. Impact of LFS on communication in social surroundings | Interviewees describing their communication within their social life, how (much) it is influenced by LFS topics and how they wished communication to be. In addition, if and why they do (not) communicate with other persons with LFS | “Two siblings of mine, I tried to talk to them several times and they absolutely refused to talk about it (…) and then it even came to the point that we have no contact at all because of this topic” | |

| IV. Daily living needs | k. Burden of the social environment due to LFS | Reactions and behaviors related to LFS of family/partners/workplace perceived by interviewees. How individuals in their social environment are dealing with the situation | “My partner is also extremely overwhelmed. So he can’t handle it when I’m not doing well” |

| l. Financial and organizational aspects | Financial consequences of LFS such as health insurance companies and reduced work life. Organizational complexities (doctors’ appointments) in everyday life | “I’m also overwhelmed with the coordination of appointments; I have to say in all honesty. Covering that alongside a full-time job” | |

| m. Coping and resources | Strategies of interviewees to cope with diagnosis and general coping in everyday life situations, including mental, physical, or social skills. In addition, if and how interviewees take care of their (physical) health | “I eat healthy, I do a lot of sports again, take care of my mental health and try not to take everything so seriously anymore and enjoy things much more” | |

- Abbreviation: LFS = Li–Fraumeni syndrome.

3.2. Psychosocial Challenges and Unmet Psychological Needs

The domain of psychological needs revealed the highest mean scores in the SCNS-SF-34 (M = 36.90, SD = 28.91). Most striking unmet needs showed the items “Uncertainty about the future” (N = 41, 58.6%), “Concerns about the worries of those close to you” (N = 37, 53.6%), and “Learning to feel in control of your situation” (N = 36, 51.4%), which are all part of the psychological needs domain (Table 2). The unpredictability of the probability of cancer associated with LFS, uncertainty, and persistent insecurity were also identified as the main triggers of fear in interviews (“Sword of Damocles,” ID 5). Each medical examination and its awaiting results were reported as repeated confrontations with LFS. Some claimed an ambivalent attitude: examination provided reassurance. When asked about psychological burdens in general in interviews, participants described the strains of cancer diagnosis and treatment itself: “I was in acute treatment for my breast cancer (…)” (ID 49) (Table 3, a). In interviews, multiple worries were described concerning cancer progression (Table 3, c): participants’ own cancer diagnosis and therapy, cancer diagnosis or loss of their relatives, including children, and the persistent uncertainty of cancer (re)occurrence. In the SCNS-SF-34, 47% reported an unmet need on the item “Fears about cancer (re)occurring due to the elevated risk” and about a third reported unmet mood-related symptoms ,“Feelings of sadness” (N = 27, 38.6%) and “Feeling down or depressed” (N = 24, 34.3%).

3.3. Unmet Needs Regarding Sexuality and Reproductive Concerns

One-quarter to one-third of participants (25.0%–33.3%) reported an unmet need on one of the three items of the domain sexuality needs (“Changes in sexual feelings,” “Changes in your sexual relationships,” and “Being given information about sexual relationships”). In our study cohort, this domain revealed the second-highest mean scores (M = 22.64, SD = 28.49). The Mann–Whitney U test revealed no significant differences between groups (single/relationship and cancer history/no cancer history), with a tendency for higher unmet needs in this scale if one is in a relationship or if a cancer history is present. Interviewees also disclosed unmet needs regarding the reproductive challenges of LFS: The perception of passing on the risk to one’s (future) children caused feelings of guilt in participants and uncertainties about whether to have children or not. Some experienced LFS diagnosis as a relief, as it provided an explanation for their familial cancer history (Table 3, b). The LFS was reported to have a substantial impact on partnerships. Partners were included in decisions revolving around LFS and assumed the role of supporter in the relationship: “It has already influenced (the relationship) because you make plans for the future differently” (ID 49). The LFS diagnosis was reported to be present and often discussed in partnerships, especially when children were diagnosed with LFS (Table 3, i). The interviewees often stated that their relationships became stronger during the LFS-associated challenges.

3.4. Unmet Health System, Organizational and Information Needs

The domain health system and information needs revealed a mean score of 26.97 (SD = 25.17). Within this domain, 40.6% and 39.1% of individuals with LFS reported unmet needs in “Being informed about cancer which is under control or receding (i.e., in remission)” and “Having one member of hospital staff with whom you can talk to about all aspects of your condition, treatment, and follow-up.” Twenty-six participants (37%) stated an unmet need for fast test results and information on self-help. Analysis of group differences revealed a significant difference (U = 284.5, Z = - 2.944, p = 0.003) between those participants with cancer history (M = 32.70, SD = 25.01) vs. no cancer history (M = 16.01, SD = 22.07) in terms of health system and information needs (Figure 3).

Regarding the health system, it was reported in interviews that there was also a struggle with the financial aspects of medical appointments for surveillance, such as coverage of travel expenses and loss of earnings (Table 3, l). At the time of interview data collection, insurance companies did not automatically cover medical appointments (especially whole-body MRI). Participants therefore reported straining “fights” (ID 33) with them. The interviewees stated the challenge of managing all surveillance dates, especially if several family members had LFS. Coordination was described as tiring. However, some were very rational in regard to these challenges: “It’s simple, it’s a must (…)” (ID 47).

3.5. Unmet Physical Needs and Daily Living Challenges

The items most relevant in the domain physical and daily living needs were “Lack of energy/tiredness” (N = 32, 45.7%), “Feeling unwell most of the time” (N = 24, 34.3%), and “Work around the home” (N = 19, 27.1%). Analysis of group differences revealed no significant differences. Interviewees reported a range of psychosomatic symptoms: irritability, uneasiness, lack of concentration, headache, sleeping problems, and gastrointestinal complaints. In addition, managing surveillance appointments concurrent with a job was perceived as challenging. “With LFS, you are not reasonable for an employer” (ID 4).

Considering the impact, LFS had on their daily life, interviewees reported several coping strategies (Table 3, m). Some have enjoyed and appreciated their life more since diagnosis, while others see the benefit of following health recommendations as a source of control (e.g., sports and nutrition). Intense research and exchange with others increased the control experience for some. Others tried to provide LFS with as little space as possible in their daily life.

3.6. Unmet Needs in Patient Care and With Healthcare Professionals

The domain patient care and support needs showed the lowest mean score altogether. It contains the two least stated unmet needs in the SCNS-SF-34 (“More choice about which hospital you attend,” and “More choice about which cancer specialists you see”). The item with the highest percentage in this domain, 35.7% (N = 25), was “hospital staff attending to patients’ physical needs promptly.” In interviews, the experiences with patient care were described ranging from positive to negative (Table 3, g). When interviewees found the right expert physician, the relationship was perceived as very close and trustworthy. Frequent and low-threshold contact with their physician was considered valuable and appreciated. Participants also experienced miscommunication, malpractice, lack of information, information overload, and time pressure, especially considering the lack of LFS experts. When in contact with healthcare professionals, the need to be taken seriously was often stated (Table 3, h). The interviewees felt that non-LFS experts considered them overreactive: “The doctors then declare you a little bit crazy” (ID 4). This was also the case when interviewees had only their cancer family history and not yet an LFS diagnosis. Participants experienced that worries about early cancer onset were overlooked. Regarding their care, interviewees underlined the importance of accessible expert knowledge of their special medical situation in psychosocial care structures (Table 3, d). When there was no current cancer diagnosis or treatment, some participants felt not seen as in need of support. Also, the interviewees reported a lack of access to LFS-related expert information (Table 3, e). A perceived knowledge gap in practitioners and feelings of being left alone were reported. Some interviewees expected more interest and engagement from care providers regarding LFS. To match their need for expert information, participants wished for a centralized source for the exchange of information, such as a permanent contact person organizing all examinations (Table 3, f). Being treated by several different practitioners and finding trustworthy practitioners was perceived as tiring (“It’s a marathon”; ID 55).

3.7. Unmet Needs Regarding the Social Surroundings

In addition to the SCNS-SF-34, interviews revealed unmet needs regarding the social surroundings of the interviewed individuals with LFS (Table 3, j). Interviewees in general preferred to deal more openly with their LFS diagnosis, even though they considered it not always possible. Participants considered sharing a cancer diagnosis easier than the underlying TP53 variant. Sharing with other individuals with LFS could be a relief. Other interviewees preferred no/less contact with other individuals with LFS, because of witnessing cancer (re)occurrences. They reported struggling to explain LFS or sharing bad news with friends, family, and children. Potential familial conflicts arose as family members handled the diagnosis differently from their own beliefs (e.g., testing of children). The interviewees also reported that they noticed worries about the future, fear, nervousness, and anger in their loved ones. However, interviewees disclosed they felt that their loved ones did not want to put themselves in the foreground (Table 3, k). In particular, male spouses were viewed as restrained in regard to their own burdens. Loved ones were often a major support for interviewees, as they gathered information or organized support.

4. Discussion

The aim of our study was to explore the uSCN of individuals with LFS. Using the SCNS-SF-34, a validated tool in psycho-oncology, we were able to identify psychological, sexual, health information and information needs domains as the most pressing for the individuals with LFS in our cohort. The results concerning uncertainties about the future, worries and feelings of control are in the upper third of known prevalence rates [24]. Our mixed-methods approach allowed us a more in-depth understanding of the unmet needs and challenges of individuals with LFS. During interviews, additional unmet needs came to the surface, which were not covered by the SCNS-SF-34: First, the organizational and financial struggles due to the intense surveillance program. Also, the impact on unmet needs regarding the social surroundings and relationships of individuals with LFS. Furthermore, a deeper understanding of the unique unmet needs regarding reproductive aspects came to the surface in interviews, in addition to the sexuality domain in the study questionnaire. Regarding the healthcare system, individuals with LFS revealed unmet needs concerning the centralization of their health information.

4.1. Comparison of uSCN Patterns

As levels and distribution of unmet needs differ between populations, integration of our results on LFS into previous research is limited [25]. Commonly associated with increased uSCN are, for example, the amount of physical symptoms, symptoms of anxiety or depression, impaired quality of life, older age, and female gender [15, 17, 24]. These need to be taken into account for our population, which is mostly female, and revealed high symptom levels [20]. Given the limited research on and uniqueness of LFS, it seems suitable to include studies on populations of rare conditions and patients with limited curation options, such as chronic diseases or advanced cancer stages [25] Also, if diseases are clearly localizable, it seems to be associated with lesser uSCN [25]. These factors need to be accounted for when canalizing data on the LFS population, as the condition itself is of genetic, incurable cause, hereditary, and with the risk of multiple onsets at any time. One-third of our participants were neither cancer patients nor cancer survivors. Comparing this third with participants who had at least one cancer, we found no significant differences between these two groups in the need domains “psychological,” “physical and daily living,” “patient care and support,” or “sexuality.” The LFS diagnosis may have an extraordinary effect on uSCN, despite cancer history: Husson et al. found similar results in a rare disease population, discussing that living with an incurable condition itself is so burdensome, even if the condition itself is stable. This might be comparable to patients under watchful waiting [25]. We also found no significant differences in any uSCN domain, despite that being in a relationship has previously been described to have a positive effect on cancer patients, for example, on fear of progression or HRQoL [26, 27]. As hinted by our comparison of mean scores, it even leads to more uSCN. This may be, for example, because the desire to have children comes to the surface, which is a difficult question for couples as our interview results revealed. We suspect that as a rare, potentially life-threatening and hereditary disease, the factors that are already difficult for the partnership in the case of cancer [28] come into play even more in the case of LFS and therefore more needs arise.

At the time of initial diagnosis of LFS, informational and health system needs are most likely to be pressing (e.g., finding experts, financing, and organizing appointments), as shown in other rare cancer populations [8]. What may influence these more practical uSCN is the socioeconomic status. Individuals with LFS in a more solid financial position may be burdened less by the mentioned struggles with health insurance companies or managing cancer surveillance while being in an employee status. When these more practical aspects are addressed for the time being, it is likely that the preexisting underlying psychosocial needs become evident. Unmet informational needs suggest that there are several open questions for individuals with LFS, despite different time points of initial LFS (or cancer) diagnosis. However, our results indicate that health information needs to become more apparent and remain highly relevant when a malignancy is diagnosed.

Compared to studies on the uSCN of “common cancers,” our results resemble uSCN patterns of rare cancer patients, for example, less prominent physical and daily living needs [8, 12]. We also see scattered similarities of unmet physical needs in patients with incurable cancer [29]. However, concerning unmet sexual needs, our sample matches the results of young adult cancer patients [15]. The term “being in a no man’s land between sickness and health” [15] seems to be suitable for individuals with LFS, explaining the mixed differences and similarities in the uSCN we see in comparison with other cancer populations. Therefore, these individuals are a unique cohort, with a unique pattern of uSCN characteristics.

4.2. Dynamics of uSCN

LFS is a lifelong and incurable condition; therefore, changes in uSCN over time need to be discussed. Previous studies revealed different dynamics of uSCN over time in different (cancer) populations. On the one hand, uSCN decreased [29], whereas otherwise remained stable [16]. The moderating and mediating factors of the uSCN over time often remain unclear [13]. Our results indicate that individuals with LFS, who had at least one cancer in the past, have more uSCN in terms of the health system and information. This supports previous research on rare cancers, as a peak in the uSCN was found in the posttreatment phase, and age-, personality- and cancer-specific factors seemed to influence the uSCN [8].

However, as we learn from cross-cultural studies, uSCN vary. LFS requires extensive engagement with the healthcare system (e.g., surveillance and therapy). Patient needs in this context may differ significantly depending on the structure and organization of healthcare provision in a given country.

The roles of identity in families with LFS are complex influencing communication patterns, coping, and claiming psychosocial support [30]. The shaping of one’s own identity and the influence on the family are different experiences for sporadic versus hereditary cancer [30]. With a hereditary cancer syndrome such as LFS, previous similarities in family dynamics with chronic illnesses, such as health behavior and therefore (non)adherence to cancer surveillance, were reported [30]. In LFS, there are different “health leader roles,” which are a transitioning responsibility and an important influence on other family members [31]. In addition, it seems that the perceived effort it costs to cope with an illness contributes to uSCN and was previously considered to be crucial when analyzing uSCN [15]. For our population, we assume a high perceived effort to cope, which may also be associated with which “role” the individual has taken on at that time. Supposedly, needs, effort to cope, and the role of the person diagnosed with LFS change, for example: a more prominent role as caregiver when a family member is diagnosed with cancer, shifting needs when being under treatment or when the relationship status changes.

5. Limitations

Considering the interpretation of our results, we first want to note that the composition of demographic variables in our participants is comparable to another questionnaire study on LFS conducted in Germany, which provides evidence for the representativeness of our study [32]. However, our data capture a particular moment, but unmet needs probably fluctuate during the trajectory of dealing with LFS. There may be other relevant factors that we did not assess, such as perceived adjustment to chronic illness, recent life events, or remote residence [15, 16, 24].

A limitation of using the SCNS-SF-34 questionnaire is that it does not provide a cutoff score for defining critical levels of the uSCN [15]. In addition, studies vary in interpreting the questionnaire, such as considering “low need” as an unmet need or not [24]. We also remark, that the SCNS-SF-34 is not validated for LFS or other CPS. However, there is no comparable validated questionnaire for LFS yet and the SCNS-SF-34 is a frequently used tool in the field of psycho-oncology [8]. Nevertheless, we found that the SCNS-SF-34 does not cover all aspects of individuals with a rare condition (e.g., tolerance in society, information on alternative treatment, and heritability) [33]. As to date, there is no questionnaire specifically designed for the condition of LFS, we suggest adding an open-ended question concerning other unmet needs when using the SCNS-SF-34 to systematically assess additional unmet needs in populations with such rare conditions [33].

Furthermore, we cannot rule out the possibility of a selection bias. We are unable to provide specific numbers regarding the recruitment pathways through which participants were enrolled. As shown in our results, individuals with LFS face many (fluctuating) challenges. It is possible that we did not reach individuals who are highly burdened and for whom participation in the study represented an additional stress factor. Our study also may have likely attracted participants who are actively engaged with LFS. However, as we learned from narratives through interviews, there are also individuals who avoid engaging with this topic. Considering our qualitative data, we need to note that the interview script was not pilot-tested and that we did not assess interrater reliability. Finally, it is worth mentioning that we conducted this study during the COVID-19 pandemic and the corresponding regulations, which may have influenced the uSCN in patients.

6. Conclusion

Our results reveal that future research needs to take a closer look at when which needs are most important for this unique group. Regular screening to evaluate the needs could help to raise awareness in individuals with LFS and their medical practitioners. Screening for current needs could be integrated into their regular medical appointments of the surveillance program, as individuals are already in contact with the medical staff. This would increase the probability to address needs more promptly when they arise. One possible approach would be to initially screen dichotomously about the presence of needs using the scales of the SCNS-SF-34, and then, if relevant, further explore the needs through the corresponding items. We also need to provide a general aid system in which individuals diagnosed with LFS can obtain the information/support they need for their current situation, as this can rapidly change for this rare and incurable condition. Therefore, psychosocial and informational support and contact information should be offered always to individuals with LFS even if they do not have a cancer diagnosis (yet).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

S.K.: design of the study questionnaire and interview script, data collection, writing and editing of the manuscript, statistical analyses, qualitative analysis, and approval of the final article.

I.M.: project development and initiation of the study, design of the study questionnaire and interview script, supervision of data analysis and data interpretation, and editing and approval of the final article.

J.R.: design of the interview script and approval of the final article.

J.N.: design of the study questionnaire and interview script, patient recruitment, data collection, editing of the manuscript, and final article approval.

M.K.: patient recruitment, editing of the manuscript, and approval of the final article.

C.M.D.: patient recruitment, data curation, review, and approval of the final article.

F.S.: patient recruitment and approval of the final article.

C.P.K.: conceptualization, project administration, patient recruitment, and approval of the final article.

S.S.: project development and initiation of the study, design of the study questionnaire and interview script, patient recruitment, supervision of data analysis and data interpretation, writing, editing of the manuscript, and approval of the final article.

Funding

S.S. and I.M. were supported by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, Federal Ministry of Education and Research, BMBF (01GM1909D). C.P.K. has been supported by the Deutsche Kinderkrebsstiftung (DKS2024.03) and Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, Federal Ministry of Education and Research, BMBF (01GM1909A). J.N. was supported by the Faculty of Medicine Heidelberg in the form of the Rahel-Goitein-Strauss fellowship. Open access funding was enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the German Li-Fraumeni Syndrome Association (LFSA) for supporting our research project and all participants for taking part in this study.

Supporting Information

Table A: Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SPQR) Checklist.

Table B: Met and unmet needs in individuals with LFS in the SCNS-SF-34 questionnaire (N = 70).

Table C: Descriptive results of SCNS-SF-34 questionnaire (N = 70).

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The quantitative and qualitative data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.