The Experiences of Female Cancer Patients Undergoing Fertility Preservation: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

Purpose: Due to the fact that a significant proportion of cancer cases occur in children and women of reproductive age, fertility preservation (FP) has become an increasingly important issue. Presenting the experiences of women who undergo these treatments from a holistic perspective will contribute to clinical practice. Most studies in the literature focus on the decision-making process. Departing from the predominant focus of previous studies on the decision-making phase, this study aims to provide an in-depth understanding of the emotional responses, challenges, and support mechanisms experienced by women throughout the entire FP process.

Methods: This descriptive qualitative study was conducted with 12 women diagnosed with cancer who underwent FP approaches. Data were collected via in-depth semistructured face-to-face interviews and concurrently analyzed via conventional content analysis.

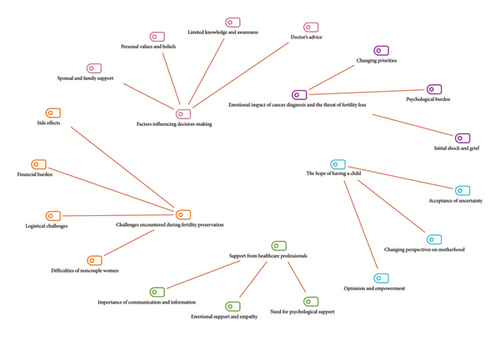

Results: The experiences of women undergoing the FP process were categorized into five main themes and 17 subthemes: the emotional impact of cancer diagnosis and the threat of fertility loss (initial shock and grief, psychological burden, and changing priorities), factors influencing decision-making (doctor’s advice, limited information and awareness, personal values and beliefs, and partner and family support), challenges encountered during FP (side effects, financial burden, logistical difficulties, and challenges faced by single women), support from healthcare professionals (importance of communication and information, emotional support and empathy, and need for psychological support), and hope of having children (optimism and empowerment, changing perspectives on motherhood, and acceptance of uncertainty).

Conclusion: Our study has provided insights into significant issues such as the decision-making process, treatment process, and emotional outcomes related to FP approaches in women with cancer.

Implications for Practice: The findings of this study highlight the need for patient-centered fertility counseling for women with cancer. Healthcare providers should offer timely and individualized information, ensure emotional support throughout the FP process, and incorporate psychosocial care into routine oncology and reproductive services.

1. Introduction

Cancer, as one of the most complex and multifaceted diseases in modern medicine, is a health issue that profoundly impacts individuals’ quality of life and future plans [1, 2]. Although the incidence of cancer increases with age, a significant proportion of cases occur during childhood, adolescence, and reproductive years [3], as reported by the World Health Organization [4]. In 2022, a total of 1,300,196 new cancer cases and 377,621 cancer-related deaths were reported globally among adolescents and young adults (AYAs) aged 15–39 years. The age-standardized incidence rate (ASR) was 40.3 per 100,000 person-years. The cancer burden among AYAs was significantly higher in females compared to males, with incidence rates of 52.9 and 28.3 per 100,000 person-years, respectively [5]. Moreover, more than one million women are diagnosed with cancer each year, and approximately 10% of these cases occur during the reproductive age [6, 7].

Cancer treatment can lead to a significant loss of reproductive capability [8–10]. Fertility preservation (FP) approaches have been developed to mitigate the fertility loss caused by cancer treatment [11–13]. FP approaches during and after cancer treatment allow patients to maintain their hope of having children in the future [2, 14]. These approaches play a protective role against the potential side effects of aggressive treatment methods such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgical interventions [14, 15].

Innovations in reproductive technology provide women with various options to preserve their fertility. The most commonly used methods for FP in women today are embryo cryopreservation, oocyte cryopreservation, and ovarian tissue cryopreservation [16]. FP in women is not as straightforward or short-term as it is in men. Unlike the rapid sperm sample storage process in men, FP in women involves creating a treatment plan for controlled ovarian stimulation followed by oocyte retrieval. Additionally, it is not always possible to obtain a sufficient number of oocytes in a single cycle to achieve future pregnancy [17], as reported by the National Cancer Institute [18]. Therefore, performing these potentially lengthy procedures in women without delaying vital treatment is a critical process [8, 19–21]. The utilization rates of FP approaches are considered relatively low. In the United States, the use of FP services among female cancer patients ranges between 4% and 20% [22]. In a study conducted in China with 313 young female cancer patients, only 19.2% had accessed FP services [23]. Similarly, in Italy, the rate of FP utilization among young women with breast cancer has been reported to be 10% [24]. Despite growing interest in the topic, our insight into women’s experiences across the full course of this process remains insufficient.

The literature predominantly addresses the decision-making processes for FP from both healthcare professionals’ and patients’ perspectives [1, 2, 9, 11, 25, 26]. Only the study conducted by Del Valle et al. in Spain has been found to evaluate women’s experiences throughout the entire FP process—from the decision-making stage to the completion of treatment. This study revealed that women diagnosed with cancer experienced intense emotional fluctuations, lack of information, concerns about reproductive capacity, and significant changes in social relationships during the FP process [27]. To the best of our knowledge, there is a lack of studies in the existing literature that explore these experiences within the unique sociocultural and healthcare context of Turkey. In Turkish society, childbearing is a major determinant of a woman’s social status within both the family and the broader community. Moreover, many infertile women experience social stigma and are frequently exposed to negative discourse [28].

The FP process encompasses a multifaceted experience that includes not only medical interventions but also the emotional, psychological, and social dimensions of patients [29]. In traditional societies such as Turkey, where fertility holds significant cultural and social value, understanding experiences related to FP is particularly important. The aim of this research is to thoroughly examine the experiences of female cancer patients undergoing FP approaches. In this context, the goal is to gain in-depth knowledge about the emotional responses experienced by patients during the treatment process, the challenges they face, and the support mechanisms available to them. The research findings will guide healthcare professionals and policymakers in developing more effective and sensitive approaches to address the holistic needs of women undergoing cancer treatment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

In this study, a descriptive qualitative design was used. The aim of a descriptive qualitative design is to obtain information from the perspective of those directly involved about their experiences, events, and interactions [30]. Since the aim of this study is to determine the experiences of female cancer patients undergoing FP approaches, the use of a descriptive qualitative design was particularly important.

2.2. Sample of the Study

The population of the study consists of female cancer patients undergoing FP approaches at a fertility center. A purposive sampling method was used in this study. Women over the age of 18 who have undergone FP approaches (oocyte/embryo/ovarian tissue cryopreservation) due to a cancer diagnosis were included in the study, while patients in the terminal stage were excluded. A total of 28 patients who underwent FP at the center where the study was conducted were considered. Of these, seven declined to participate and nine did not meet the inclusion criteria; therefore, they were excluded from the study.

Since all data collection was conducted by Melek Hava Köprülü, it was noted that similar topics were discussed during the 10th interview. To ensure data saturation, two additional interviews were conducted, reaching a total of 12 participants [31]. Upon completing the data analysis, it was determined that 12 interviews were sufficient, as no new themes emerged, indicating that data saturation had been reached. To confirm this, two members of the research team (Menekşe Nazlı Aker and Neslihan Yılmaz Sezer) reviewed the transcripts to verify that data saturation had been achieved.

The participants’ ages range from 21 to 39. Seven of the participants are single. The eight of the participants’ have a university degree. Only one of the participants achieved pregnancy using frozen materials (Table 1). Participants had no previously diagnosed or known fertility problems.

| Document name | Age | Marital status | Educational status | Economic status | Diagnosis | Current health status | Fertility preservation method | Pregnancy status with frozen material |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 21 | Single | University | Good | Ependymoma, CNS tumor Type 2 | Bad |

|

No |

| P2 | 24 | Single | University | Middle | Hodgkin’s lymphoma | Bad | Oocyte C | No |

| P3 | 30 | Married | University | Middle | Breast Ca. | Bad |

|

No |

| P5 | 25 | Single | High school | Middle | Hodgkin’s lymphoma | Good | Ovarian tissue C | No |

| P6 | 32 | Single | University | Middle | Multiple Myeloma | Good |

|

No |

| P7 | 33 | Single | High school | Middle | Breast Ca. | Good |

|

No |

| P8 | 34 | Married | University | Middle | Hodgkin’s lymphoma | Good |

|

No |

| P9 | 27 | Married | University | Low | Rectum Ca | Bad |

|

No |

| P10 | 32 | Single | University | Middle | Breast Ca. | Good | Oocyte C | No |

| P11 | 39 | Married | University | Middle | Lymphoma | Good | Embryo C | No |

| P12 | 34 | Single | High school | Low | Breast Ca. | Bad |

|

No |

| P13 | 26 | Married | Primary school | Middle | Hodgkin’s lymphoma | Good |

|

Yes |

- ∗C: Cryopreservation.

2.3. Data Collection

In this study, a descriptive information form and a semistructured in-depth interview form were used (Table 2). The interviews were conducted individually between December 2023 and June 2024. The interviews were conducted individually. During the interviews, recordings were made with the participants’ consent. The interviews lasted 30–40 min.

| 1. What are your feelings and thoughts about fertility when you first received the diagnosis? |

| 2. What are your feelings and thoughts about fertility after completing the fertility preservation process? |

| 3. Could you describe your decision-making process regarding fertility preservation? |

| 4. Could you discuss your experiences with the fertility preservation process? |

| 5. What difficulties did you encounter during the fertility preservation procedures? How did you cope? |

| 6. Could you describe the support systems available to you during the fertility preservation process? |

2.4. Analysis of the Data

The study data were analyzed using MAXQDA software. To ensure that no assumptions were made about the themes and that the findings were based solely on the data presented, inductive content analysis was employed [32]. The audio recordings of each participant’s interviews were transcribed verbatim, and separate Microsoft Word documents were created for each. Each transcript was imported as a single document into the MAXQDA project. To maintain anonymity and personalize the findings, participants were coded as Pi (P: participant; i: participant number).

A six-phase guide was used to conduct the analyses and ensure the accuracy of the inductive content analysis process [33]. The transcribed interviews were read multiple times for familiarity, and notes were taken. Initially, the transcripts were examined individually, and initial codes were generated. Subsequently, the coded data were grouped to identify broader themes. The three authors met multiple times to discuss and organize the emerging codes and themes. In the iterative process of analysis, similarities and differences were explored by moving back and forth, progressing from the whole to the parts and then back to the whole. This process ensured the clarification of the themes. The fourth author reviewed the themes and examined the quotes to verify their accuracy and check for any potential inconsistencies. The identified themes were reported with support from direct quotations. The methods and findings were reported in accordance with the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guidelines [34].

2.5. Rigor

To ensure the reliability of the analysis, three researchers participated in the analytical process. The fourth author reviewed the themes and examined the quotes to check for potential inconsistencies and verify accuracy [35]. The reliability of this study was enhanced by ensuring that the participants were relevant to the study’s purpose and by achieving data saturation. All interviews were conducted by a single researcher. When similar topics were identified during the 10th interview, two additional interviews were conducted to achieve data saturation, resulting in a total of 12 participants. The analysis revealed that no new themes emerged and data saturation had been achieved. Two members of the research team reviewed the transcripts to confirm this situation. Data saturation means that no new information related to the research purpose is obtained through additional interviews with extra participants [36]. The first author was familiar with the research topic due to previous related studies and having conducted a systematic literature review; however, to ensure that any biases did not affect the analysis or reporting of results, they remained objective throughout the process. To enhance the credibility of the research, the interviews were recorded. Additionally, the concepts and themes emerging from the raw data were organized and presented without adding interpretation or altering the nature of the data, with direct quotations included. The original direct quotations in Turkish were translated into English to enhance the authenticity of the results.

2.6. Ethical Aspect of the Study

Ethical approval (Date: 06.20.2023; Number: 11/97) was granted by an ethics committee of a university before the commencement of the study. All participants were informed about voluntary participation, and written informed consent was obtained.

3. Results

The FP experiences of women undergoing cancer treatment are described through five main themes and 17 subthemes (Figure 1).

3.1. Theme 1: Emotional Impact of Cancer Diagnosis and the Threat of Fertility Loss

“When I first received the lymphoma diagnosis, I was in shock. I had no health problems, and there was no such history in the family; no one had ever had cancer. Of course, you question life. Why did this happen to me? Will I be able to live through it? If I survive, will I be able to have children? You cry asking these questions.” (P11)

“I never thought I would have a fertility issue until the doctor told me. When I first received the diagnosis, I only thought about my health. Will I be able to recover? How will this happen? The fear, the sadness, it was something like that. I got upset when I was alone. We acted like nothing was wrong at home, but I was very sad again when I lay down alone at night.” (P10)

“At that time, of course, I was initially thinking about my treatment. Then my brother directed us here, saying that the treatment might harm my ovaries. I’m glad he did. Otherwise, they would have likely been harmed. With chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery, I would have lost my chance to have children. That would have been an even greater trauma for me, honestly.” (P9)

3.2. Theme 2: Factors Influencing Decision-Making

“How did I decide? Actually, it was my doctor who recommended it. The doctor who performed my surgery directed us here. I believe fertility, especially as a woman, holds a very important place in our lives. That’s why we accepted it with little questioning.” (P1)

“I had no information at all, of course. Then, when I learned that I had cancer, my doctor said that the medications would severely damage my ovaries, and that I needed to start the freezing process immediately. After that, I learned about it and came here. I started the process.” (P12)

“I initially thought it was unnecessary, but later, when my mother and other doctor friends commented that my opinion might change in the future, I decided to proceed with it. So, we made this decision before even getting married. Well, it was difficult for me, of course.” (P7)

“Honestly, my family supported me a lot, both my father and my mother. They insisted that I definitely needed to do it. Because I might regret it in the future if I cannot have children. They said that even if you don’t want it right now, you will want it in some way in the future.” (P1)

3.3. Theme 3: Challenges Encountered During FP

“The side effects may have included irritability and emotional sensitivity. Let’s say sensitivity, my period was a bit delayed, and I experienced some bloating in my abdomen towards the end. I didn’t experience these issues with the first injections, but I had severe pain with the subsequent injections. Yes, it did make me feel a bit uncomfortable.” (P6)

“Yes, it’s definitely a financial burden. I was already incurring significant expenses. I was going back and forth for my treatment; unfortunately, it’s a situation that requires financial resources.” (P5)

“Just making sure to keep track of the medication times and being very punctual with them. I struggled a bit with that. I set alarms, or it was a period when I couldn’t leave the house anyway. But still, it was challenging to do it precisely on time.” (P6)

“Everyone there was a couple. It felt like everyone had a spouse and they were there for another treatment. Coming and going alone was, to be honest, a bit challenging for me. Without a partner, I was constantly confused about whether preserving my fertility was truly a sensible thing to do. To be honest, I didn’t feel very happy when I arrived there. I was coming there reluctantly. Since my mother was very supportive, she said that maybe after recovery, you might want to have children. Let’s have it available. Because I was actually not inclined towards having children. I usually came alone, which made me unhappy.” (P6)

3.4. Theme 4: Support of Healthcare Professionals

“When I learned about the diagnosis in the first week, I asked, ‘Will I not be able to have children?’ Despite being a doctor myself, I had no knowledge about it at all. Then, by asking my friend, I got some idea; honestly, I didn’t have much knowledge. I completely left myself to the doctors and nurses, and I did not encounter any crises, problems, or difficulties. The process proceeded very smoothly.” (P3)

“I was actually surprised by the support I received. I mean, in terms of respect and compassion, you are also very good. Honestly, you helped me get through about 50% of this process more easily. During the egg freezing process, I felt at ease largely due to the support of the nurses, healthcare professionals, and doctors. They played a crucial role, contributing significantly—about 50%—to my comfort and ability to navigate through this process.” (P11)

“Psychological support is not enough. I, for example, would have expected such support, to be honest. It is necessary. Because it is very overwhelming during that period. For example, I was 22 years old when I faced this. I had already encountered cancer at that age. I was battling battling with that idea in my mind, because I have to start a treatment. You haven’t even started the treatment yet and you don’t know what you will face. This psychology got ahead of cancer for a while. At that moment, I did not have the means to seek psychological support on my own. I was already incurring significant expenses.” (P8)

3.5. Theme 5: The Hope of Having a Child

“Honestly, I am very happy and very excited. (Sobbing). I’m glad I did it. Because I work with children and I’m looking at them and say “Why shouldn’t I have one of my own?” When I think, ‘Why shouldn’t I have one of my own?’ the freedom to do so whenever I want makes me feel more at ease. Maybe I will never do it, or maybe I will. Because this desire is within me and is based on my own wishes, I am happy and I can do it if I want to.” (P13)

“I never used to think about getting married beforehand. Now I want to get married and have a child as soon as possible. I suppose that, in this way, motherhood has become even more precious to me.” (P12)

“I thought, ‘It’s destiny.’ I thought that if these things are happening to me, there must be some good in it. You cannot overcome some things without accepting them as part of fate. If I look at it as hope, I don’t actually feel like I won’t have a child. But it seems like it won’t be part of my plans for a long time.” (P5)

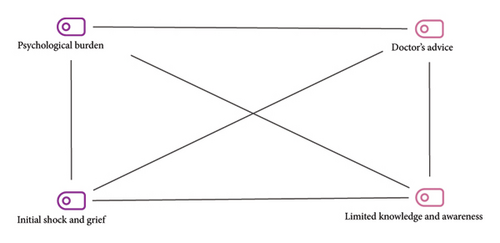

When participants provided feedback on the Initial Shock and Grief code, they also frequently provided feedback on the Psychological Burden code. Similarly, when they provided feedback on the Doctor’s Advice code, they also frequently provided feedback on the Limited Information and Awareness code (Figure 2). Participants coded as P12 and P2 summarize the situation from their perspective as follows:

3.6. The Initial Shock and Grief—Psychological Burden

“When I first received the diagnosis, I was very shocked and sad. I didn’t know what to do. Because I was thrust into a very rapid process. With all the anger and sadness, I don’t even know how I ended up here.” (P12)

3.7. Doctor’s Advice—Limited Knowledge and Awareness

“I had no information about this. I was completely unaware. I didn’t think I would have any issues with fertility until the doctor mentioned it.” (P2)

4. Discussion

The themes derived from this study on the FP experiences of women undergoing cancer treatment provide valuable insights into the complexity of these experiences.

Women reported feeling intense shock and grief when diagnosed with cancer and the risk of fertility loss. A life-threatening diagnosis often triggers an immediate shock response [37]. During this highly vulnerable period, patients must come to terms with their illness and make rapid treatment decisions. In addition, they are expected to take steps toward FP as part of these urgent plans [9]. In the process of FP alongside a cancer diagnosis, women frequently reported experiencing a significant psychological burden due to the uncertainty of the future and the physical and emotional challenges of cancer treatment. Peddie et al. [9] reported that women experienced negative emotions related to FP following a cancer diagnosis. These women, whether they hoped for the return of their fertility or not, believed that by delaying potentially life-saving treatment, they would lose much and gain little [9]. During this period, women feel scared and under pressure because they have to make quick decisions [9, 19–21, 38–40]. When diagnosed with a life-threatening risk, the most important concern for patients, following the initial shock reaction, is survival [8, 12, 41]. Once the diagnosis is understood and treatment options are outlined, patients’ priorities may change [1]. In this study, women reported that their priorities had shifted, with the desire to have children in the future becoming a source of hope and motivation.

In our study, it was observed that several factors influenced the FP decision-making processes of the participating women. Under this theme, the most frequently expressed subtheme was doctor’s advice. The advice and guidance of oncologists and fertility specialists play a crucial role in initiating the FP process. Therefore, it is believed that interdisciplinary communication and collaboration between oncologists and fertility specialists can enhance patient care. In our study, women frequently expressed having limited knowledge and awareness about FP prior to their diagnosis. Studies highlight the need to inform patients. However, healthcare professionals often do not provide adequate information about fertility risks and options [1, 8, 10–12, 25, 41–45]. These findings indicate that issues related to limited information for patients remain an ongoing and current primary concern. The support and encouragement from spouses and family members played a significant role in the decision-making processes of the women participating in our study. In many cases, men have been reported to play crucial supportive roles in women’s FP decision-making processes [26, 46] and experiences [46]. Besharati et al. [47] also highlighted the importance of family support in the process of FP for young adult cancer patients [47]. It is important to provide care that evaluates and strengthens the support systems of women undergoing FP. In our study, women expressed that their personal values and beliefs regarding family, motherhood, and personal health significantly influenced their decision-making processes. Baysal et al. [48] reported that women’s desire to become pregnant and have children in the future plays a significant role in their FP decisions [48]. Carroll et al. [49] stated that women chose to undergo FP not primarily for career balancing or the pursuit of having “it all” but largely out of hope for “love” and the desire to have “healthy babies” of their own [49].

The women who participated in our study reported encountering various challenges during the FP process. The difficulties experienced by women due to the medications they used have been addressed under the subtheme of side effects. During the FP process, the most common complaints associated with controlled ovarian stimulation include hormonal mood swings, hot flashes, abdominal pain, headaches, bloating [50, 51], and anxiety about injections [52]. Additionally, the treatment process, monitoring appointments, frequent injections, and uncertainties about treatment success can lead to emotional and physical stress for women [14, 50, 51]. Therefore, planning nursing care for women undergoing FP in terms of potential side effects is crucial. FP approaches impose a significant financial burden on women. In our country, the lack of insurance coverage for FP methods places an additional financial burden on patients. In a study, the most frequently encountered barriers to FP identified as the lack of insurance coverage for the procedures and the significant financial burden on patients (both at 62%). The same study also shows that Turkey is one of the highest-cost countries for FP approaches [2]. However, patients who embark on this path with determination face not only financial burdens but also various logistical challenges associated with FP approaches. This further complicates the logistics of cancer treatment. Despite all these frequently experienced challenges, unmarried women often reported feeling isolated and socially stigmatized during the FP process. Notably, the previous research has documented similar issues in different contexts. For example, Baldwin and Culley found that many women undergoing social egg freezing described the process as emotionally challenging, largely due to feelings of isolation and stigma associated with their single status [53]. Similarly, Kim and Kim reported that women undergoing oocyte cryopreservation for non-cancer-related reasons experienced negative judgments and discomfort stemming from intrusive questions and societal perceptions [54]. However, it is important not to neglect this specific group, which requires additional support, as their needs differ from those of women with partners during this sensitive period.

In our study, women highlighted the importance of support from healthcare professionals during the FP process. The study revealed that during the period of FP following a cancer diagnosis, women needed psychological support. The psychological and emotional support, communication, and empathy provided by healthcare professionals played a crucial role in helping them cope with the challenges they faced. Additionally, women emphasized the need for clear and compassionate communication from healthcare professionals throughout the entire FP process. One study examined the FP decision process of women diagnosed with breast cancer from the perspective of a health professional. The findings indicated that nurses, in particular, appeared highly engaged and utilized every opportunity during patient interactions to emphasize the importance of FP discussion and its potential impact on the woman’s future quality of life. In the same study, it was also acknowledged by other respondents that FP counseling is an integral part of nursing care. The reason for this is the nurses’ opportunities to engage in discussion with women and address the psychosocial aspects of cancer diagnosis [11]. The supportive role needed during the FP process can be provided by a nurse or social worker specifically trained in FP [55].

The final theme of our research was identified as the hope of having children. Under this theme, the most frequently expressed subtheme was the change in perspective on motherhood. Taniskidou et al. [26] also reported that postcancer FP significantly impacts women’s attitudes toward biological parenthood, with many women experiencing an increased desire for parenthood compared to their previous aspirations. In the same study, patients who had considered motherhood before their cancer diagnosis reported higher levels of anxiety and distress compared to younger participants who were not ready for motherhood [26]. However, regardless of the patient’s desire to have children, FP became essential in some cases and even took precedence over their cancer diagnosis. Under the subtheme of optimism and empowerment, women expressed a sense of empowerment from having control over their fertility options, despite the challenges of the process. Dyer and Quinn [1] reported that oncologists participating in their study believed their patients felt overwhelmed, scared, or anxious by the details of their diagnosis, and that fertility concerns were overshadowed by other worries at the time. However, they believed that patients who did not have children would start thinking about fertility again after recovering from their illness [1]. Assi et al. [56] suggested that young cancer patients who underwent FP experienced positive emotions such as trust and hope, and that the hope of raising children after a cancer diagnosis could contribute to better acceptance of oncological treatment and its side effects [56]. The negative emotions experienced by women following a cancer diagnosis can evolve over time, giving way to more positive feelings such as optimism and empowerment. A supportive approach from healthcare professionals during this period can further strengthen these positive emotions. On the other hand, implementing FP approaches does not guarantee success, and studies are ongoing to increase the chances of success [57]. The women who participated in our study expressed awareness of the uncertainty surrounding success, and while they remained hopeful, they also acknowledged the uncertainty of future fertility and expressed willingness to accept various outcomes. Offering women accurate information and emotional support can facilitate their adherence to treatment plans in the face of uncertainty.

4.1. Limitations

This study provides valuable insights into the experiences of female cancer patients undergoing FP; however, there are several limitations to consider. First, the sample size of 12 participants may not fully represent the diverse experiences of all women with cancer, particularly those from different socioeconomic backgrounds or with varying cancer types. Additionally, as the data were collected through in-depth interviews, the findings may be subject to recall bias, as participants may have difficulty accurately recalling specific experiences or may be influenced by their current emotional state. The study was conducted in a specific geographic area, limiting the generalizability of the results to other populations or regions.

5. Conclusion

This study, aimed at revealing the experiences of female cancer patients who underwent FP approaches, revealed that women initially experienced negative emotions but later began to prioritize the continuation of their fertility. Women’s personal values, knowledge and awareness, doctor recommendations, and support from partners and family have influenced their decisions regarding FP procedures. Women experienced side effects, financial and logistical difficulties, and emotional challenges, particularly feelings of loneliness among unmarried women. While emphasizing the positive impact of healthcare professionals’ support, women have also expressed the need for additional psychological support. Despite all the challenges, women have also experienced positive outcomes such as optimism and empowerment with the hope of having children, a change in their perspective on motherhood, and an acceptance of uncertainty.

Our study has provided insights into significant aspects such as decision-making processes regarding FP approaches, treatment processes, and emotional outcomes. This information can guide the optimization of FP programs, enabling healthcare providers to better support their patients and empowering patients to make more informed decisions about FP approaches. The results of this study will help nurses and other members of the infertility team to better understand the challenges and opportunities encountered during the implementation of FP approaches. It also provides important information on how FP programs can be improved in the future.

6. Implications for Practice

The findings of this study underscore the necessity of providing individualized fertility counseling to women diagnosed with cancer at the early stages of their treatment. The results also highlight the need for continuous emotional and psychological support throughout the FP process. Establishing multidisciplinary teams—including oncologists, reproductive health specialists, nurses, and mental health professionals—would enable more coordinated and holistic support for patients. In particular, nurses play a critical role in initiating FP-related discussion, providing ongoing counseling, and addressing the psychosocial impacts of fertility loss.

As observed in our study, the feelings of loneliness and stigma experienced by unmarried women in couple-oriented fertility clinics indicate their specific need for targeted support. Therefore, service delivery should incorporate appropriate planning that acknowledges and addresses the unique needs of this group.

Systematic solutions should be developed to reduce logistical and financial barriers. Participants reported difficulties in managing frequent appointments, medication schedules, and financial burdens. Therefore, assigning FP coordinators—such as dedicated nurses or social workers—within hospitals could help streamline the process and improve continuity of care.

Implementing these recommendations may enhance the patient experience during the FP process and support healthcare professionals in delivering more effective patient management. It is important to integrate these improvements into clinical practice and to evaluate their effectiveness in future research. Follow-up studies based on monitoring and evaluation frameworks could be designed to assess the impact of these interventions on patient satisfaction, emotional well-being, and service efficiency.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Menekşe Nazlı Aker, Neslihan Yılmaz Sezer, Gülşah Kaya, and Batuhan Özmen; methodology: Menekşe Nazlı Aker and Neslihan Yılmaz Sezer; formal analysis: Menekşe Nazlı Aker, Neslihan Yılmaz Sezer, and Melek Hava Köprülü; resources: Menekşe Nazlı Aker, Neslihan Yılmaz Sezer, and Melek Hava Köprülü; data curation: Gülşah Kaya, Melek Hava Köprülü, and Batuhan Özmen; writing – original draft: Menekşe Nazlı Aker, Neslihan Yılmaz Sezer, and Melek Hava Köprülü; writing – review and editing: Menekşe Nazlı Aker, Neslihan Yılmaz Sezer, Gülşah Kaya, and Batuhan Özmen. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

All authors have contributed significantly, and all authors are in agreement with the content of the manuscript. The authors take full responsibility for the content of the article. The authors have contributed to, seen, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No financial assistance was received for this research.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants for being a part of this study.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request due to privacy/ethical restrictions.