A Case of Branch Retinal Artery Occlusion With Concomitant Intraocular and Extraocular Toxoplasmosis Lesions in a Japanese Man

Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of the study is to report a case of ocular toxoplasmosis with branch retinal artery occlusion (BRAO).

Case: The patient was a 36-year-old man from Okinawa, Japan, who was generally healthy and had no medical history. He was referred to our hospital with a complaint of sudden loss of vision in the left eye. Best corrected visual acuity was 0.1 in the left eye at the initial examination, and intraocular pressure was 21 mmHg. Anterior segment slit-lamp examination showed a few cells of the anterior segment and anterior vitreous. Fundus examination of the left eye showed retinal vasculitis of the middle and large retinal vessels with occlusion of retinal arterioles in the macular area and edema in all layers of the retina, with dense posterior vitreous cells and flare. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a mass shadow at the posterior part of the left eyeball near the macula in the orbit. On laboratory examination, toxoplasma serum IgM and IgG were positive. Based on these results, he was diagnosed with BRAO with concomitant intraocular and extraocular toxoplasmosis. He was then treated with clindamycin, sulfamethoxazole–trimethoprim, and steroids. The inflammation disappeared quickly, and visual acuity improved to 0.6. The inflammation had not flared up even 3 months after the initial visit with decreasing serum toxoplasma serum IgG levels, and the posterior eyeball shadow on the MRI disappeared.

Conclusion: A case of BRAO with uveitis with concomitant intraocular and extraocular toxoplasmosis lesions was presented. In cases of unilateral retinal vasculitis with orbital lesions, concomitant intraocular and extraocular toxoplasmosis should also be considered.

1. Introduction

Ocular toxoplasmosis is a rare disease, but it has been reported as one of the leading causes of uveitis. Although studies vary, toxoplasmosis generally accounts for approximately 1%–30% of uveitis cases [1, 2].

Toxoplasma is an intracellular parasitic protozoan parasite whose end host is the cat, and humans are intermediate hosts. It is transmitted to humans through oocysts in feline feces or by eating undercooked meat from cattle, pigs, chickens, or other intermediate hosts infected with toxoplasma [3].

Ocular toxoplasmosis has been reported to cause a variety of ocular fundus diseases. Atypical symptoms have been reported in the literature, including optic neuropathy, angiogenesis, retinal vascular occlusion, epiretinal membrane, and retinal detachment [4]. A case of branch retinal artery occlusion (BRAO) caused by toxoplasma in a young man with no previous history of the disease is reported.

2. Case

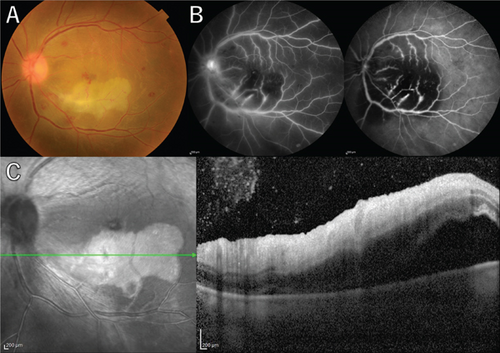

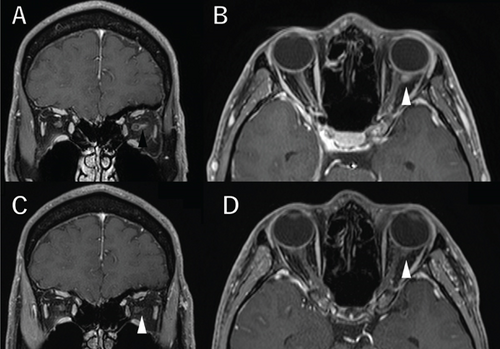

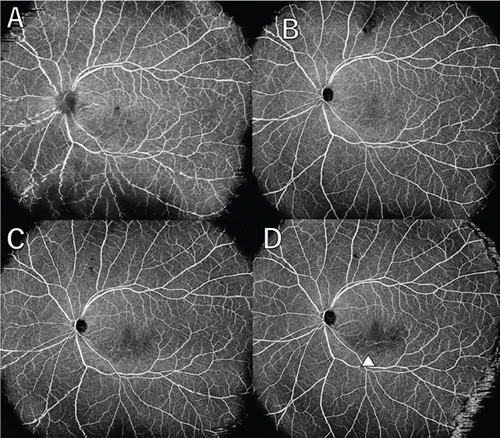

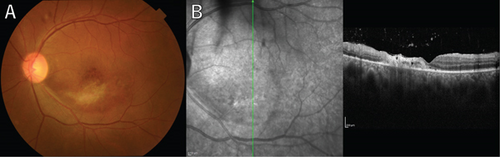

A 36-year-old man with a chief complaint of a sudden loss of vision in the left eye that began 1 day earlier was referred to our department after a visit to his previous doctor who found BRAO. The patient had been in good health and had no underlying disease. The left eye’s best corrected visual acuity was 0.1. No abnormalities were found in the light reflex, with no relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD). There was no inflammation in the anterior segment of the eye. Fundus examination of the left eye showed retinal vasculitis of the middle and large retinal vessels with occlusion of retinal arterioles in the macular area and edema in all layers of the retina (Figure 1A). Goldmann perimetry (GP) showed decreased sensitivity and central darkening consistent with a vascular occlusion area; fluorescein angiography (FA) showed delayed filling in the inferior part of the left eye arcade, and leakage from the optic disc in the early phase and hypofluorescence in the late phase (Figure 1B) were also observed. Ocular coherence tomography (OCT) showed intraretinal edema, serous retinal detachment, and vigorous vitreous cells in the left eye (Figure 1C). There was no leak in the peripheral vessels. Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with left BRAO. Since the patient was a young man with no medical history, uveitis was suspected, and he was hospitalized for close examination and treatment after collecting anterior chamber fluid for comprehensive multiplex real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing by previous reported methods [5–7]. The anterior chamber fluid was negative for comprehensive infections. Prednisolone 125 mg and prostaglandin E1 as a vasodilator were administered intravenously for optic papillitis, and the patient was carefully watched for worsening inflammation. After betamethasone eye drops were started, vitreous inflammation worsened, and inflammation in the anterior chamber appeared. Anterior segment slit photography showed posterior corneal deposits and anterior chamber cells, and steroid administration was discontinued. Suspecting infectious retinitis, gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the orbital region was performed and showed a mass shadow at the posterior part of the left eyeball in the orbit (Figure 2A,B). In addition, both toxoplasma serum IgM and IgG were positive, suggesting current infection (Table 1). Then, treatment for ocular toxoplasmosis was started with clindamycin 2400 mg and sulfamethoxazole–trimethoprim 3840 mg for 8 weeks. The intravitreal inflammation gradually improved, and the patient was discharged from the hospital. The retinal white matter lesions disappeared after discharge, and OCT and en-face ultra-widefield optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA) showed thinning of the vascular occlusions compared to at the onset of the disease (Figures 3A, 3B, 3C, 3D, 4A, 4B, and 4C). The final visual acuity improved to LV (0.6), and the orbital lesion in MRI showed that the contrast effect of the mass shadow in the posterior part of the left eyeball has diminished (Figure 2C,D) after 10 months later.

| Hematology | Result | Reference range | Unit | Serology | Result | Reference range | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC | 5900 | 3300–8600 | μL | CRP | 0.01 | 0–0.14 | mg/dL |

| RBC | 456 × 10 | 435–555 | 103/μL | IgG | 991 | 861–1747 | mg/dL |

| Hb | 12.2 | 13.7–16.8 | g/dL | IgA | 197 | 93–393 | mg/dL |

| Ht | 37.6 | 40.7–50.1 | % | IgM | 57 | 36–245 | mg/dL |

| Plt | 32.4 × 10 | 158–348 | 103/μL | RF | 2< | 0–15.0 | IU/mL |

| PT sec | 11.1 | 9.8–12.1 | s | HTLV-I ab | — | 0–1.0 | — |

| PT-INR | 0.96 | 0.90–1.14 | — | HPV-1 IgM | — | 0–0.80 | — |

| VZV IgM | — | 0–0.80 | — | ||||

| Biochemistry | Toxoplasma IgM | 1.2 | 0–0.80 | — | |||

| AST | 22 | 13–30 | U/L | Toxoplasma IgG | 134 | 0–6.0 | — |

| ALT | 29 | 10–42 | U/L | HIV | — | — | |

| ChE | 293 | 208–311 | U/L | TB IFN-γ | — | — | |

| UA | 5.4 | 2.8–7.8 | mg/dL | STS | — | — | |

| BUN | 14 | −20 | mg/dL | TPHA | — | — | |

| Cre | 0.88 | 0.65–1.07 | mg/dL | ||||

| Na | 141 | 138–145 | mmol/L | ||||

| K | 4.5 | 3.6–4.8 | mmol/L | ||||

| Cl | 104 | 101–108 | mmol/L | ||||

- Note: Bold values indicate clinically significant findings.

The patient has been under observation with decreasing toxoplasma serum IgG antibody levels for the past 6 months without any worsening.

3. Discussion

A case of BRAO with uveitis accompanied by concomitant intraocular and extraocular toxoplasmosis lesions, in unilateral retinal vasculitis with orbital lesions, was described. This is the first case of ocular toxoplasmosis inside and outside the orbit with BRAO and examined using multimodal imaging.

In general, the diagnostic standard for uveitis of unknown origin is multiplex PCR, an established method for excluding an infectious origin, as reported by Sugita et al. and Nakano et al. [5, 7] In the present case, the results of two anterior chamber aqueous humor PCRs were both negative, and the positive results for toxoplasma IgM and IgG led to the diagnosis of ocular toxoplasmosis. The sensitivity of real-time PCR of intraocular fluid in protozoan-infected uveitis has been reported to be 57% [8]. In particular, the sensitivity and specificity for ocular toxoplasmosis have been reported to be low [9]. Although the sensitivity is low, it is inferred that PCR sensitivity may be higher in the vitreous, which is closer to the lesion, given that toxoplasma is a protozoan. In addition, epidemiological studies in Japan have reported that the infection rate of Toxoplasma gondii is high in animal hosts in the southwest islands of Japan, especially Okinawa, and although accurate national data do not exist, it is thought that work history and residential history are also important in cases of ocular toxoplasmosis [10]. Of course, there is a possibility of mother-to-child transmission, and it is unclear how a healthy young man who was not a compromised host developed the disease at this time. We suspect that the infection may have been acquired, but we are not certain.

It has been reported that BRAO occurred in 7% of ocular toxoplasmosis cases [11]. The cause was mentioned as direct compression of arteries (retinal vessels) or adjacent active retinitis lesions by inflammatory foci, vasoconstriction, and increased blood viscosity [11]. These speculations are supported by prior reports of retinal vasculitis and vascular occlusion in ocular toxoplasmosis [3, 12–14]. Furthermore, based on the results of experimental verification using monkeys, we speculated that the pathology was consistent[15]. As a limitation, in this case, Toxoplasma gondii mRNA was not detected in the intraocular fluid, so it was not a definitive diagnosis, but rather a diagnosis of exclusion. In the present case, the lesion was located in the posterior aspect of the eye near the optic nerve, which showed a contrast effect on orbital MRI, and inflammatory spillover from there may have caused the BRAO.

Reports of MRI findings in ocular toxoplasmosis are rare, but there are reports of circumferential contrast effects along the optic nerve [16]. There have been several reports of retinal choroiditis after steroid administration for optic nerve inflammation [17].

In the present case, as well, the worsening of inflammation after steroid treatment led us to consider infectious retinitis. Therefore, when administering steroids to young patients with optic nerve inflammation without a history of previous treatment, the fundus should be carefully monitored for the possibility of infectious lesions.

The present case also suggested, in particular, that, especially with regard to toxoplasmosis, a comprehensive diagnosis of infection by multiplex PCR is not all powerful, and a detailed and accurate medical history and key imaging evaluations are what formed the basis of the ocular toxoplasmosis diagnosis.

In conclusion, BRAO with uveitis with concomitant intraocular and extraocular toxoplasmosis lesions was described. In unilateral retinal vasculitis with an orbital lesion, concomitant intraocular and extraocular toxoplasmosis should be considered.

Nomenclature

-

- MRI

-

- magnetic resonance imaging

-

- BRAO

-

- branch retinal artery occlusion

-

- OCT

-

- ocular coherence tomography

-

- RAPD

-

- relative afferent pupillary defect

-

- GP

-

- Goldmann perimetry

-

- FA

-

- fluorescein angiography

-

- PCR

-

- polymerase chain reaction

Ethics Statement

Institutional review board approval was not required for this study, in accordance with the local guidelines.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of the details of his medical case and the accompanying images.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Gen Kinari, Mizuki Tagami, Mami Tomita, Norihiko Misawa, Atsushi Sakai, and Yusuke Haruna cared for, worked up, treated, and collected data from the patient. Taro Shimono and Shigeru Honda analyzed the ophthalmological findings and gave critical suggestions. Mizuki Tagami performed the operation, and Gen Kinari prepared the manuscript. Gen Kinari, Mizuki Tagami, Mami Tomita, Norihiko Misawa, Atsushi Sakai, Yusuke Haruna, Taro Shimono, and Shigeru Honda read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number 23K09013 [Mizuki Tagami]).

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.