Miltefosine Failure and Amphotericin B Success in the Treatment of a Case of Cutaneous Leishmania Braziliensis in a Recent Traveler in Belize and Guatemala

Abstract

We report the case of a 53-year-old male with recent travel to Guatemala and Belize who was diagnosed with cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL). He was treated empirically with miltefosine with no improvement and switched to amphotericin B upon species identification of L. braziliensis, resulting in the resolution of his lesions. This case demonstrates that clinicians should recognize the importance of systemic therapy for treating complex CL, as well as the importance of identification of species type for tailoring treatments. Furthermore, while miltefosine has proven efficacious for CL in many New World locales, it has demonstrated lower cure rates for CL in Guatemala, and thus identification of the region of origin of the CL infection is imperative for further guiding treatment, which may vary according to the differences in drug potency or region-specific resistance rates.

1. Background

Leishmaniasis is a vector-borne infection caused by the protozoan parasite Leishmania and transmitted by the female sandfly [1]. Clinical infections may be categorized into three main syndromes: cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) characterized by cutaneous ulcers, mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (MCL) characterized by mucosal and cartilaginous involvement, and visceral leishmaniasis (VL), also called kala-azar leishmaniasis, characterized by internal organ involvement [2]. The manifestation of the disease depends on the Leishmania species, which is largely categorized into those found in the Old World, referring to the Mediterranean, the Middle East, Africa, and India, and those found in the New World, referring to the Americas [1]. As infections caused by different Leishmania species often require different treatment approaches, it is critical to identify Leishmania species for optimal management. Herein, we report the case of a 53-year-old male with recent travel to Guatemala and Belize who was diagnosed with CL, treated empirically with miltefosine with no improvement, and then switched to amphotericin B upon species identification of L. braziliensis, resulting in the resolution of his lesions.

2. Case Presentation

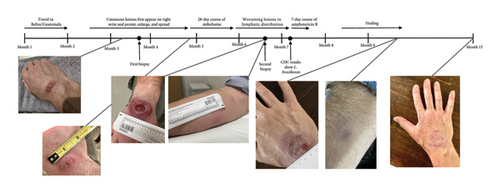

A 53-year-old male previously in good health traveled to Belize and Guatemala for one month. His trip involved several rigorous hikes through rural jungles and included camping overnight in remote areas with minimal shelter (Figure 1). He endorsed multiple insect and spider bites. After returning to the United States 2 weeks later, he noticed a new small lesion on the right wrist. Clinical examination revealed a 0.5 cm circular, raised, erythematous papule with central ulceration on the dorsal aspect of the right wrist (Figure 2). The patient denied fevers, congestion, rhinorrhea, and sore throat. The patient endorsed weight loss and fatigue, although he attributed these symptoms to his trip. Repeat clinical examination 1 month later revealed a large, 4.5 cm erythematous plaque with central ulceration on the dorsal aspect of the right wrist and several new, tender, subcutaneous nodules with linear extension along a lymphatic distribution on the right forearm.

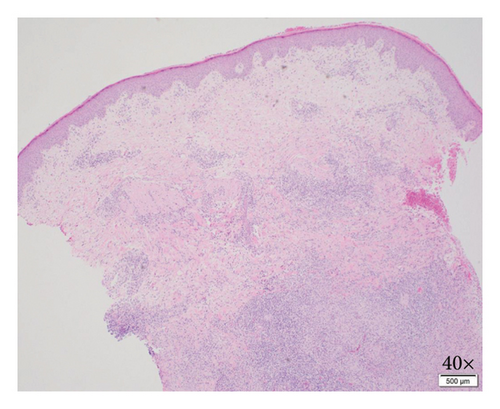

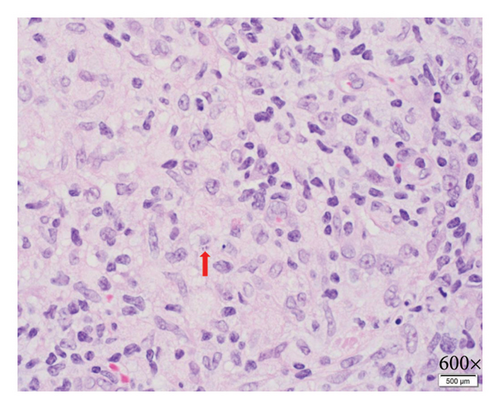

Biopsy at an outside institution revealed small hematoxylinophilic, round, uniform intracytoplasmic amastigotes distributed around the outer rim of vacuoles (marquee sign) within histiocyte–macrophage components, morphologically suggestive of Leishmania amastigotes (Figure 3). The biopsy was formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE). The specimen was sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), where Leishmania was confirmed, but species ID could not be performed on the FFPE tissue, so the patient was recommended to return to the clinic and undergo a second biopsy. Videostroboscopy and nasal endoscopy demonstrated no nasal or upper aerodigestive lesions.

The patient was diagnosed with CL and treated empirically with a 28-day course of miltefosine at 2.5 mg/kg/day while awaiting a second biopsy to be sent to the CDC for Leishmania species identification. Although the patient experienced mild nausea with the first few doses of miltefosine, he was able to tolerate the medication and complete the total course as prescribed. Six weeks after completing the miltefosine course, the patient failed to demonstrate improvement. At that time, results from the CDC from the second biopsy returned, identifying Leishmania braziliensis as the causative species. The patient was then started on liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome®) at 3 mg/kg for 7 days (cumulative dose of 1858.5 mg), which he tolerated well with some fatigue and nausea and transiently raised creatinine levels that resolved. Eventually, the patient experienced resolution of the lesions and upon follow-up 2 months later had not experienced recurrence of any lesions.

3. Discussion and Conclusions

Management of CL depends on the Leishmania species, which is often predicted by the region of origin. According to recent clinical guidelines, patients may be categorized as having simple or complex CL. Patients are categorized as having complex CL if they have any of the following: Leishmania species typically associated with MCL; greater than 4 lesions that are greater than 1 cm in diameter; individual lesion greater than or equal to 5 cm; local subcutaneous nodules or large regional lymph nodes; lesions on the face, digits, joints, or genitalia; immunocompromised status; or failure of treatment [4, 5]. Those with simple CL with lesions that have not yet begun to heal may be treated with local therapies, whereas those with simple CL with lesions that have already begun to heal may be observed [4, 5]. Those with complex CL should be treated with systemic therapy. Our patient satisfied several of the criteria for being categorized as complex CL, including single lesions eventually growing to greater than or equal to 5 cm, involvement of lymphatic nodules, and failure of treatment.

Given that speciation of leishmaniasis cultures requires outsourcing to a limited number of reference laboratories and thus take time to result, the decision was made to empirically treat the patient with systemic treatment with miltefosine [4, 5]. Our patient acquired the disease in either Belize or Guatemala, which border each other. In Guatemala, several studies conducted in the 1980s and 1990s revealed that most CL lesions (73%–75%) were due to L. braziliensis, with the next most prevalent species being L. mexicana. Although L. braziliensis is commonly associated with MCL, MCL has rarely been reported in Guatemala [6]. The data on Leishmania in Belize are more sparse. One Belize CL study on British troops touring in Belize in the early 1990s found that in 306 soldiers with a clinical diagnosis of CL, 187 cases had parasitological confirmation, of which, 78 were identified as L. braziliensis and 29 as L. mexicana, and none with MCL [7]. There have also been a handful of published case reports of leishmaniasis originating from Belize, with all caused by either L. braziliensis or L. mexicana. [8–10].

Miltefosine (Impavido®) is the first and only oral drug approved by the United States’ Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat CL, including that caused by L. braziliensis [11]. It is an alkylphosphocholine drug that is generally well tolerated, with the exception of gastrointestinal side effects, such as nausea and vomiting [11]. The endemic region in which the infection is acquired, however, affects miltefosine’s efficacy. Although Bahia, Brazil, and Guatemala are both regions in which L. braziliensis predominate, the cure rate for CL with miltefosine was 85% in Bahia, Brazil, yet only 48% in Guatemala [12]. The data regarding miltefosine efficacy for CL in Belize are even more limited. Interestingly, one case report described two cases of CL due to L. braziliensis in Dutch military personnel acquired in Belize that were treated successfully with oral miltefosine [13].

Given that our patient experienced worsening lesions despite completing treatment with miltefosine, it is possible that our patient may have acquired the infection in Guatemala rather than Belize, though it is impossible to confirm. Given the progression of disease after completion of miltefosine therapy, the patient was started on amphotericin B. Amphotericin B is a polyene drug that has been approved by the FDA to treat VL, though it has been used for complex CL as well. Although highly effective, amphotericin B carries several severe side effects including nephrotoxicity, which may be offset by saline loading in patients prior to dosing. The liposomal amphotericin form is often preferred due to its less severe side effect profile. After completing treatment with amphotericin B, our patient experienced subsequent healing of his lesions. He did have a transient creatinine increase to 1.76. With hydration, this normalized to his baseline creatinine of 1.10.

In conclusion, clinicians should recognize the importance of systemic therapy for treating complex CL and of the identification of species type and region of acquisition for tailoring treatments for CL. Furthermore, while miltefosine has proven efficacious for CL in Colombia, it has demonstrated lower cure rates for CL in Guatemala. Thus, identification of the region of origin of the CL infection is imperative for further guiding treatment, which may vary according to differences in drug potency or region-specific resistance rates [14–17].

Nomenclature

-

- CL

-

- Cutaneous leishmaniasis

-

- MCL

-

- Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis

-

- VL

-

- Visceral leishmaniasis

Ethics Statement

The authors have nothing to report.

Consent

The patient has provided written informed consent for publication, which is available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Michelle Y. Ko was responsible for conceptualization, data curation, investigation, visualization, writing–original draft, writing, review, and editing. Emilie Fowler was responsible for conceptualization, supervision, writing, review, editing, and patient care. Amanda Scott was responsible for conceptualization, supervision, writing, review, editing, and patient care. Daniel Z. Uslan was responsible for conceptualization, supervision, writing, review, editing, and patient care.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Sharon Roy from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for critical clinical input. We would like to acknowledge Dr. Chandra N. Smart from the Department of Pathology at the University of California, Los Angeles, for performing and providing histopathologic imaging.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The authors have nothing to report.