Resilience and Environmental Performance of SMEs: The Mediating Role of Ambidextrous Green Innovation

Abstract

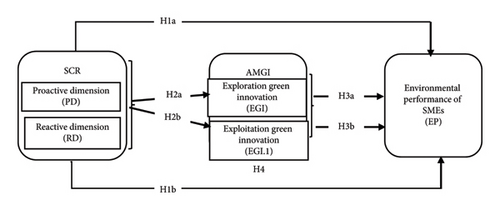

The disruptions in supply chains have put small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in dire need of resilient supply chains through which they can improve their performance. Based on the resource dependence theory, this study proposes a mediation model to improve the environmental performance (EP) of SMEs. The purpose of this study is to investigate the effect of supply chain resilience (SCR) on EP mediated by ambidextrous green innovation (AMGI). We proved a structural equation model based on questionnaire data from 261 companies in Iraq to test our hypotheses. The results show that SCR has a positive effect on AMGI for proactive and exploitative green innovation dimensions and positive impact on SMEs’ EP. AMGI plays a mediating role and positively affects EP in dimensions. Building SCR requires management support through proactive and reactive measures to address disruption risks. AMGI necessitates integration with supply chain members, including external suppliers and customers, and involves them in developing a corporate strategy that supports environmental issues. By emphasizing EP improvement, this study will guide practitioners in developing innovative techniques that contribute to improving the EP of SMEs and urging decision-makers to support SMEs that include EP within their strategy.

1. Introduction

In recent years, supply chains have become increasingly complex and vulnerable to disruptions. Statistics reveal that approximately 65% of firms experience at least one supply chain disruption annually, and around 13% suffer losses exceeding one million euros as a result [1]. The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the fragility of global supply chains, causing significant disruptions for three years [2]. In response to such challenges, SCR has appeared as a critical capability enabling firms to expect, absorb, and recover from disruptions. Unlike risk management which focuses on minimizing threats, SCR emphasizes building adaptive capacity and can be seen as a strategic opportunity to enhance firm performance [3]. Prior research shows that SCR contributes positively to environmental performance (EP), especially by improving the firm’s responsiveness to regulatory and market pressures [4, 5].

SMEs contribute to approximately 70% of global industrial pollution [6], yet often lack the awareness, ability, and resources necessary to adopt effective environmental practices [7, 8]. Addressing these challenges requires a nuanced understanding of how innovation can drive environmental improvement in SMEs, particularly through ambidextrous green innovation (AMGI), a concept derived from the ambidexterity theory that combines exploratory (radical and future-oriented) and exploitative (incremental and efficiency-driven) green innovation strategies. AMGI refers to developing and implementing environmentally friendly practices and technologies that are adaptable and versatile. AMGI originated from the ambidextrous innovation theory, which seeks direct organizations in the pursuit of exploration and exploitation innovations concurrently to reach a competitive edge. Scientists have extended this hypothesis to incorporate green innovation, resulting in the birth of AMGI [9]. According to Shehzad et al. [10] and Cancela et al. [11], companies should invest in exploitative innovation (EI.1) and exploratory innovation (EI), contributing to improved performance and the companies’ success. Hence, the significant focus on EI.1 shows the ability to adapt to change, causing knowledge to become obsolete and eventually reducing the competitiveness of organizations.

Excessive emphasis on exploration innovation simultaneously reduces operational efficiency and increases negative costs and returns, especially when organizations work in unexpected situations. Corporate organizations have the persistent challenge of avoiding the adverse outcomes of excessive exploitation, commonly known as the “success trap,” and the negative repercussions of overexploitation, referred to as the “failure trap.” This goal requires achieving a balanced and mutually beneficial combination of environmentally friendly practices and exploration to enhance economic, social, and environmental value simultaneously [12]. Furthermore, the success of new products is enhanced by green product innovation due to the growing demand for environmentally sustainable products [11], especially in emerging economies [10].

SMEs lack awareness of their environmental impacts or adequate responses to relevant environmental concerns. Several studies have shown that SMEs have limited resources and devote less time to understanding and addressing environmental regulations [7]. Furthermore, SMEs have little knowledge of the consequences of adopting environmental practices and their impact on their financial well-being and ability to continue to innovate [8]. A study by Shashi et al. [6] showed that an orientation toward sustainability positively impacts the EP of SMEs. In a similar vein, Zhang and Mohammad [5] found that SCR positively impacts EP. Furthermore, some companies tend to adopt green supply chains as a tool to improve their EP. Nazir et al. [13] found a meaningful relationship between green supply chain management practices and the EP of manufacturing firms. Although these studies focused on EP solutions for SMEs, they assumed that the dimensions affecting EP remained constant. In this study, we will focus on this gap.

SMEs face significant challenges in balancing SCR and enhanced EP. With supply chain disruptions and increased focus on environmental issues, there is a need to understand how SCR can contribute to improved EP. However, the mediating role of AMGI (proactive and exploitative) stays insufficiently studied, limiting the ability of companies to develop effective strategies to improve their EP. This study attempts to fill the research gap by examining the mediating influence of AMGI on the link between SCR and EP. SCR is crucial in enhancing an organization’s capacity to adjust, react, and bounce back from internal and external disruptions, enhancing overall performance [14]. Taking proactive and reactive actions contributes to SCR directly. Therefore, it will positively impact on the EP of SMEs. On the other hand, SMEs may receive help from EI and EI.1 to achieve the most significant positive impact on their EP. Therefore, AMGI can play a mediating role.

Despite growing interest in SCR and its effects on EP, the mediating role of AMGI in this relationship stays underexplored, particularly in the SME context. Several studies have suggested that combining exploratory and exploitative green innovation enhances overall firm performance [10, 11], but little is known about how these dynamics unfold in resource-constrained environments during times of disruption. This study looks to fill this gap by examining the mediating role of AMGI (both exploratory and exploitative) in the relationship between SCR and EP in SMEs. It aims to advance theoretical understanding by articulating how ambidextrous innovation works under external pressures and constrained resources. The findings can inform strategic planning for SMEs looking to strengthen both their resilience and EP through a balanced and context-sensitive innovation approach.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Supply Chain Resilience

The concept of SCR has garnered significant interest from both scholars and practitioners. This is mostly owing to the multitude of disruptive events that can occur and their ability to greatly damage corporate competitiveness and continuity [15, 16]. According to Alshahrani and Salam [17] and Feng et al. [18], system continuity and recovery refers to a system’s capacity to sustain its intended operations before disruptions occur and to swiftly restore its normal operations in the event of disruptions. Alternatively, SCR may also denote the capacity to shift towards a more helpful condition [19]. Hence, the ability of an organization to adjust, react, and bounce back from both internal and external disturbances can enhance the competitive edge and overall success of a company [14, 18]. Shashi et al. [3] proposed the concept of an SCR, which refers to the system’s ability to adapt, evolve, and transform in response to dynamic observations at various scales. This includes interactions between interconnected organizations, institutions, and social and environmental systems that make up the larger supply chain.

El Baz et al. [4] tried to study the contributions of the flexible supply chain in mitigating the massive disruption caused by the novel coronavirus and improving the company’s financial performance. This study’s results showed the significant positive impact of the flexible supply chain mitigating the pandemic’s disruption effects. Adobor [20] presents a comprehensive framework that defines SCR as a higher-level concept resulting from the incorporation of resilience at the human, organizational, and interorganizational levels. The paradigm encompasses interactions at many levels and elucidates how activities at lower levels positively influence the SCR. In 2017, Chowdhury and Quaddus conducted a study that showed SCR to be a complex and hierarchical concept, consisting of three fundamental dimensions: proactive capability, reactive capability, and supply chain design quality. In the same vein, Feng et al., [18] state that the main differences in SCR are based on two aspects: the scope of influence and the attributional level. Some treat SCR solely as a reactive capability within the scope of influence, while others consider it as both a reactive and proactive part. The company views SCR as its capability at the attributional level.

Proactive SCR enables SMEs to expect potential disruptions and incorporate environmental considerations into their sourcing strategies in advance, such as adopting clean technologies or diversifying green suppliers. Conversely, reactive SCR can mitigate environmental damage through adaptive practices, such as reducing waste during crisis recovery. Tukamuhabwa et al., [21] found a connection between disruption threats and SCR strategies. Therefore, strategies should be considered together because their implementation may reinforce or contradict others. We can apply these strategies to maximize their synergy if they complement each other. Belhadi et al. [22] measure SCR in all three phases of disruption: preparedness, which occurs before the disruption, response, and recovery, which occurs after the disruption. This conceptualization aligns with the earlier literature emphasizing the need to restore equilibrium following unexpected disruptive events.

2.2. SCR and EP of SMEs

SMEs are significant contributors that wield substantial influence on domestic economies. SMEs often lack awareness of their environmental impact and the requisite ability or understanding to address environmental concerns effectively. Multiple studies have shown that SMEs have limited resources and are less capable of dedicating time to understanding and addressing regulations [7, 23]. According to the findings of Majid et al. [8], SMEs have little knowledge about the effects of adopting eco-efficiency practices on their financial well-being and ability to continue innovation. Shashi et al. [6] noted earlier that the trend towards sustainability positively affects the EP of SMEs through the integration of the supply chain. In addition, they showed that supply chain integration is internal and external integration: external integration positively affects overall performance, internal integration positively affects sustainable development, overall performance positively affects overall performance and not product performance, and sustainable development positively affects product performance and product production.

Companies view SCR as a dynamic capability that helps them manage change dynamically to achieve sustainable high performance. Without resilience, we cannot achieve sustainable performance [5]. Measuring performance and building resilience-related infrastructure at the focal firm are insufficient; therefore, measuring outcomes and building infrastructure at the end of SCR partners are important [3]. Zhang and Mohammad [5] found that SCR positively affects three key pillars of sustainable performance, one of which is EP. On the other hand, Alshahrani and Salam [17] conducted a study to test the impact of SCR on the performance of SMEs. Their findings revealed a strong and positive correlation between SCR and SME performance.

- •

H1. The proactive (H1a) and reactive dimensions (H1b) of SCR positively impact on the EP of SMEs.

2.3. SCR and AMGI

Green innovation encompasses creating novel concepts, actions, goods, and procedures that aid in diminishing environmental impacts or reaching predetermined sustainability aims. Global supply chain participants are motivated to adopt green innovations mostly due to the need to meet consumer demand for environmentally friendly products [25]. Yang and Singhdong [9] examined AMGI at the microlevel of organizations, encompassing product and technology levels. They classified AMGI into two main dimensions: the first focuses on exploitative green innovation, while the second explores exploration green innovation. Their findings suggest that companies can enhance their supply chain capabilities through AMGI. However, Chege and Wang [26] examined the correlation between technological innovation and environmental sustainability and how it affects the performance of small firms. The primary focus of their research was to evaluate the extent to which SMEs have adopted sustainable practices.

- •

H2: SCR positively impacts on EGI (H2a) and EGI.1 (H2b).

2.4. AMGI and EP of SMEs

- •

H3: EGI (H3a) and EGI.1 (H3b) have a positive impact on EP.

- •

H4: The proactive (H4a) and reactive (H4b) dimensions of the impact of SCR on SMEs’ EP are mediated by the AMGI.

3. Methodology

The study adopts a quantitative approach to examine the impact of SCR on the EP of Iraqi SMEs through green innovation. Data were collected from a sample of 261 participants being 89 SMEs across Iraq (see Table 1). The sampling method followed a purposive sampling approach, targeting companies that met the criteria for SMEs (1–500 employees) and that were directly impacted by supply chain disruptions following the COVID-19 pandemic. To enhance representation, we ensured sectoral and regional diversification, selecting companies from Baghdad (50%), the southern governorates (19%), and the northern governorates (31%).

| Sample characteristics | Category | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Firm age | 2–4 years | 119 | 45.6 |

| 5–7 years | 51 | 19.5 | |

| 8–10 years | 57 | 21.8 | |

| Over 10 years | 33 | 12.6 | |

| Director | 55 | 21.1 | |

| Business operation managers | 46 | 17.6 | |

| Supervisor | 117 | 44.8 | |

| Industry | Food industry | 89 | 34.1 |

| Electrical industries | 13 | 5.0 | |

| Construction equipment | 44 | 16.9 | |

| Pharmaceutical industries | 5 | 1.9 | |

| Home furniture | 109 | 41.8 | |

| Firm size | 1–29 | 37 | 14.2 |

| 30–59 | 24 | 9.2 | |

| 60–99 | 49 | 18.8 | |

| 100–149 | 56 | 21.5 | |

| 150–249 | 63 | 24.1 | |

| 250–500 | 31 | 11.9 | |

3.1. Measures

This study relied on a five-point Likert scale, which measures all questionnaire constructs (strongly disagree = 1 and strongly agree = 5).

Supply chain resilience. Feng et al. [18] employed a distinction, derived from Cheng and Lu [33], that categorizes SCR into proactive and reactive dimensions. Two distinct four-item scales were independently adopted to measure proactive and reactive SCR.

AMGI. In this study, we relied on the division provided by Robb et al. [34]; and this division is based on two dimensions: the first, the exploration of green innovation, and the second, the exploitation of green innovation. Each dimension consists of four elements.

EP. The approved scale for this variable was constructed using five basic elements, drawing from the works of Zhang and Mohammad [5], Rodríguez-Espíndola et al. [29], and Alraja et al. [35].

3.2. Questionnaire Design and Data Collection

Prior to the final data collection phase, the questionnaire underwent a three-stage validation process: (1) preliminary interviews with 15 senior managers to identify key contextual factors relevant to Iraqi SMEs, (2) development of measurement items based on a comprehensive review of the literature, and (3) a pretest involving 14 executives to refine the instrument for clarity and content validity (see Table 2). To mitigate common method bias (CMB) and enhance response reliability, the questionnaire was divided into two sections, each completed by a different respondent within the same firm (e.g., operations manager and environmental officer). Part A captured demographic data and supply chain resilience, while Part B addressed EP and green innovation practices.

| Construct | Recourse | Item |

|---|---|---|

| Proactive dimension |

|

|

| Reactive dimension |

|

|

| Environmental performance |

|

|

| Exploration green innovation |

|

|

| Exploitation green innovation |

|

|

Added procedural controls were implemented to ensure consistency and reduce social desirability bias. These included matching respondents with overlapping roles or shared responsibilities, providing standardized instructions for completing the questionnaire, and ensuring full anonymity of responses. We evaluated all responses using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 to 5. Researchers widely use the Likert scale as a quantitative measure to gauge views and attitudes on diverse topics [19]. The questionnaire was distributed to the companies concerned electronically, and with the help of representatives of these companies, we collected 261 valid questionnaires for analysis, achieving a statistically acceptable response rate of 81% [36].

3.3. Reliability and Validity

We analyzed the reliability and validity of the measurement models, including internal consistency, indicator reliability, reliability testing, and exploratory factor analysis (EFA). All dimensions showed acceptable reliability according to Cronbach’s alpha of 0.810. We extracted five main dimensions that aligned with the constructs in the scales (Table 3). To show the validity of our findings, we performed confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The results showed that the measurement model had outstanding fit indices, with a root mean square error (RMSE) value of 0.0602 and a standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) value of 0.0220. All composite constructs (CR) showed a reliability exceeding 0.7, with item loadings ranging from 0.510 to 0.919. Additionally, all average variance extracted (AVE) values were higher than 0.5, as shown in Table 3.

| Construct | Item | Factor loading analysis | Cronbach’s alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD | SPD1 | 0.510 | 0.749 | 0.843 | 0.552 |

| SPD2 | 0.692 | ||||

| SPD3 | 0.736 | ||||

| SPD4 | 0.546 | ||||

| RD | SRD1 | 0.880 | 0.786 | 0.893 | 0.845 |

| SRD2 | 0.748 | ||||

| SRD3 | 0.660 | ||||

| SRD4 | 0.574 | ||||

| EP | EP1 | 0.824 | 0.751 | 0.848 | 0.731 |

| EP2 | 0.713 | ||||

| EP3 | 0.551 | ||||

| EP4 | 0.521 | ||||

| EGI | AEI1 | 0.626 | 0.909 | 0.939 | 0.903 |

| AEI2 | 0.919 | ||||

| AEI3 | 0.919 | ||||

| AEI4 | 0.891 | ||||

| EGI.1 | BEI1 | 0.953 | 0.761 | 0.907 | 0.915 |

| BEI2 | 0.619 | ||||

| BEI3 | 0.830 | ||||

| BEI4 | 0.787 | ||||

The measurement constructs employed in this study were adapted from well-established scales in prior research. However, to ensure contextual relevance within the Iraqi SME environment, we conducted expert interviews and pretesting to verify content validity. Given the postconflict and postpandemic operational challenges faced by Iraqi SMEs, the selected constructs particularly those relating to SCR and green innovation were considered applicable. While most items showed acceptable factor loadings (> 0.6), a few items such as SPD1 showed lower but still acceptable values (loading = 0.510). These items were kept because they contribute conceptually to the construct’s meaning and were supported during the expert validation process. Removing them would have weakened the theoretical integrity and content coverage of the scales.

Nevertheless, we acknowledge potential limitations in the measurement model. Cultural and contextual factors may influence how respondents interpret certain items, despite our efforts in pretesting and adaptation. Future studies could receive help from employing mixed methods (e.g., qualitative validation) or longitudinal designs to strengthen construct validity and generalizability.

3.4. CMB

CMB may significantly impact the relationship between different dimensions because the same respondents provided measures of external and internal variables [37]. We applied procedural methods, such as creating short intervals between independent and dependent measurements, improving the questionnaire design, changing the language and order, and adopting statistical methods, most notably Harman’s one-factor test, to ensure that CMB did not affect this study. SPSS 25 was used to perform Harman’s one-factor test. The analysis revealed that the first part accounted for a mere 38.416% of the overall variance, which fell short of the 50% threshold. Consequently, there was no significant CMB [5, 18, 37]. In addition, since the latent root value exceeds one, the cumulative explanation value exceeds 80%.

4. Results

This study used hierarchical regression and the PROCESS model with process restructuring to evaluate the proposed overall model and test the study hypotheses, in addition to conducting correlation analysis (see Table 4). We examined the impact of proactive responses (PD), reactive responses (RD), and SCR on EP using SPSS 25. Next, we examined the impact of PD, RD, and SCR on AMGI and then delved into how AMGI affects EP. Finally, we examined how AMGI mediates the impact of PD, RD, and SCR on EP. Table 5 presents the results of the hierarchical regression model.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD | 0.742 | ||||

| RD | 0.124∗ | 0.919 | |||

| EP | 0.087 | 0.685∗∗ | 0.855 | ||

| EGI | 0.141∗ | 0.846∗∗ | 0.739∗∗ | 0.950 | |

| EGI.1 | 0.114 | 0.855∗∗ | 0.760∗∗ | 0.910∗∗ | 0.957 |

| Mean | 3.3094 | 3.8400 | 3.651 | 3.7107 | 3.8716 |

| SD | 0.67676 | 0.46465 | 0.4034 | 0.59577 | 0.51497 |

- Note: The bold values indicate the square roots of the average variance extracted (AVE) for each variable.

- ∗indicates significance at p < 0.05.

- ∗∗indicates significance at p < 0.01.

| Hypotheses | β | p value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | 0.435 | p = 0.05 | Supported |

| H1a | 0.087 | p = 0.159 | Not supported |

| H1b | 0.685 | p = 0.001 | Supported |

| H2 | 0.564 | p = 0.05 | Supported |

| H3 | 0.766 | p=0.001 | Supported |

| H4 | 0.569 | p = 0.001 | Supported |

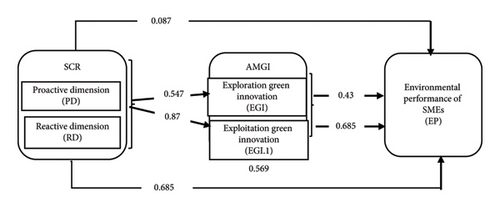

We expect H1a and H1b to have a positive effect on EP. Model 1 in Tables 6 and 5 shows that PD has no positive effect on EP (β = 0.087 and p = 0.159), whereas Model 2 shows that RD has a significant positive effect (β = 0.685 and p = .001). Therefore, we do not support H1a, but we do support H1b. At the aggregate level, SCR shows a positive effect (β = 0.435 and p = 0.05).

| Control variable | EP | AMGI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | |

| Firm size | 0.002 | 0.064 | 0.036 | 0.006 | −0.023 | 0.016 | 0.024 | 0.026 | 0.014 |

| Firm age | −0.017 | −0.129 | −0.082 | −0.163 | −0.142 | −0.157 | −0.145 | −0.022 | −0.191 |

| Industry | −0.046 | 0.023 | −0.023 | 0.038 | 0.012 | 0.015 | −0.006 | −0.026 | 0.013 |

| PD | 0.087 | 0.132 | 0.141 | 0.114 | |||||

| RD | 0.685 | 0.870 | 0.846 | 0.855 | |||||

| SCR | 0.435 | 0.569 | 0.564 | 0.547 | |||||

| AMGI | 0.766 | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.008 | 0.469 | 0.190 | 0.587 | 0.017 | 0.757 | 0.324 | 0.318 | 0.300 |

| F | 1.994 | 229.216 | 60.558 | 368.098 | 4.572 | 807.234 | 123.978 | 120.603 | 110.844 |

| t | 1.412 | 15.140 | 7.782 | 19.186 | 2.138 | 28.412 | 11.135 | 10.982 | 10.528 |

| p value. | p = 0.159 | p = 0.001 | p = 0.001 | p = 0.001 | p = 0.001 | p = 0.001 | p = 0.001 | p = 0.001 | p = 0.001 |

H2 predicts that SCR will have a positive effect on AMGI and its dimensions, EGIa and EGI.1b. In Tables 5 and 6, Models 8 and 9 show that SCR has a significant positive effect on EI (β = 0.564 and p = 0.05) and on EI.1 (β = 0.547 and p = 0.05). However, after considering everything, SCR has a bigger effect on AMGI (β = 0.569 and p < 0.05). Thus, H2 is confirmed. On the other hand, H3 predicts that AMGI will have a positive effect on EP. Model 7 in Table 6 shows that AMGI positively affects EP (β = 0.766 and p = 0.001). Thus, H3 is supported (see Figure 2).

The study proposes that H4 indicates that AMGI has a role in connecting SCR and EP dimensions. The findings in Tables 5 and 6, namely Models 5 and 8, demonstrate that AMGI mediates the link between PD and EP, supporting hypothesis H4a. Table 6 demonstrates that Models 2, 9, and 11 provide evidence for the mediation of the link between RD and EP by AMGI, hence supporting H4b.

This study employed the process-macro program to perform mediation analysis and quantify the total effect, direct effect, and indirect effect to ensure the reliability and validity of the findings [28]. Table 7 illustrates bootstrap resampling, with a random sample 2000 and a confidence interval of 0.95. Thus, the results align with the comparable findings in Table 7, confirming the validity of the prior analytical results and providing evidence for the hypothesis.

| Total effect | SE | Direct effect | SE | Indirect effect | Results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect effect | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | ||||||

| PD ->AMGI -> EP | 0.0521 | 0.0369 | −0.0082 | 0.0241 | 0.0603 | 0.0261 | 0.0102 | 0.1099 | Partial mediation |

| RD ->AMGI ->EP | 0.5949 | 0.0393 | 0.0664 | 0.0704 | 0.5285 | 0.0805 | 0.3645 | 0.6823 | Full mediation |

| SCR ->AMGI ->EP | 0.4050 | 0.0520 | 0.0008 | 0.0453 | 0.4058 | 0.0373 | 0.3375 | 0.4810 | Partial mediation |

| SCR ->EI ->EP | 0.4050 | 0.0520 | 0.0256 | 0.0472 | 0.3794 | 0.0341 | 0.3138 | 0.4498 | Full mediation |

| SCR ->EI.1 ->EP | 0.4050 | 0.0520 | 0.0253 | 0.0449 | 0.3797 | 0.0397 | 0.3038 | 0.4571 | Full mediation |

Despite the robustness of the analytical methods used, caution should be exercised when interpreting these results. For example, the conclusion that AMGI fully mediates the effect of RD on EP does not rule out the influence of other unobserved variables, such as organizational culture, environmental pressures, and financial constraints. Furthermore, the sample includes firms from diverse sectors, sizes, and regions, but the analysis does not explore whether the strength of the relationships varies across these contextual dimensions.

Recognizing these limitations, future research is encouraged to examine sectoral or regional moderating effects and to employ longitudinal designs to better understand the causal dynamics. A more precise understanding of when and how AMGI mediates the relationship between resilience and EP would enrich both the theory and practice.

5. Discussion and Implications

This study aims to investigate the relationship between SCR and EP in SMEs, discusses the direct effect of both SCR dimensions (PD and RD) on EP and AMGI dimensions (EGI and EGI.1), and considers the mediating effect of AMGI. We conducted a survey questionnaire on SMEs in Iraq using hypothetical models, leading to the following conclusions:

First, the study results show that SMEs in Iraq rely more on RD than PD to improve their EP. This is attributed to the fragile nature of the Iraqi environment, characterized by weak infrastructure, scarce resources, and political and economic instability. These factors limit companies’ ability to adopt proactive strategies that require long-term investment, making RD more realistic and possible. This finding is somewhat similar to many studies that have indicated the positive effect of SCR on firms’ EP, but they differ at the level of subdimensions [3, 5, 13, 17, 24]. However, these studies only emphasize inter-relationships, while our results show that SCR requires more detail to understand how it affects SMEs’ environmental issues, which supports decision-makers with a deeper understanding of the requirements for adopting environmental issues.

Second, the study shows that AMGI, especially dimension EGI.1, plays a pivotal role in strengthening the relationship between SCR and EP. This can be explained by the fact that AMGI gives companies the ability to develop innovative solutions that are tailored to the local environment and create a green corporate image that is difficult to imitate. These results align with the conclusions drawn by Abdallah et al. [25], W. Cheng et al. [27], and Purnomo et al. [38]. According to the existing literature [34] [28], EGI.1 carries greater risks than EGI, as it helps improve the quality of products and services by exploring and developing new environmental knowledge, technologies, and capabilities. EGI.1 is conducive to creating a positive green corporate image, which is difficult to imitate and surpass, to meet potential market and customer needs, and to form a distinct competitive advantage for the company.

Finally, our results show that EGI and EGI.1 fully mediate the relationship between SCR and EP; while at the aggregate level; AMGI partially mediates the effect of SCR on EP. The results show that the dimensions of AMGI have the same direct and indirect effects. The weak proactive actions of SMEs toward environmental issues suggest the need for firm-level improvements to enhance their EP. Interestingly, PD indirectly supports ED through AMGI rather than directly, which explains why SMEs require AMGI to improve their EP and highlights the importance of AMGI as a mediating variable.

5.1. Theoretical Implication

This study contributes positively to the theoretical literature on SCR, AMGI, and EP in several ways. First, we enrich SCR topics by emphasizing its positive role, as existing studies focus on the roles of technology [2], capabilities [22], or limited resources on SCR, such as collaboration and integration. In addition, this study agrees with Feng et al. [18] on improving proactive and reactive SCR, which contributes to improving the capabilities of SMEs to deal with supply chain disruptions, especially in emergency situations. We can implement proactive strategies such as risk assessment, mitigation, and diversification and reactive ones such as supplier relationship management and planning.

Secondly, this study focuses on two segments of AMGI, specifically EGI and EGI.1, aligning with the trends found by Sun and Sun [28]. This division gives effective ways for SMEs to find innovative solutions or deal with existing technologies, thus balancing short- and long-term goals for dealing with green innovation, finding proper methods to achieve it, and encouraging employees to do so. Conversely, this division enhances SMEs’ ability to concentrate and understand each section’s needs with greater clarity, enabling them to implement suitable strategies for each area, a premise this study relied on.

Third, we reveal the hidden mechanism by which SCR affects corporate performance through the mediating role of AMGI. Previous studies have investigated how SCR is built under certain crises or how SCR affects firm performance. While studies such as Huang et al. [19] have focused on firm performance in stable environments, our study proves that the same factors may not produce the same results in fragile environments, needing a reconsideration of generalizing theoretical findings without contextual analysis. Other studies have examined how SMEs’ EP is affected by green practices [35], how leadership is affected [31], or how EP impacts a firm’s financial performance [30]. While we still lack a comprehensive understanding of how SCR impacts SMEs’ EP, previous studies have shown that adopting circular economy principles for sustainable innovation [29] and digitalization [32] contributes to SMEs’ EP. Given the limited resources of SMEs, we believe that their EP requires a deeper and broader understanding. We have shown that AMGI serves as a mediating variable between SCR and EP, with AMGI being a mediating variable applicable to the cases showed by Baron and Kenny [39].

5.2. Managerial Implications

Iraq is one of the most environmentally impacted countries, resulting in the loss of a significant portion of its water resources and the significant increase in desertification [40]. Currently, the government has begun implementing several stringent environmental regulations, including those for SMEs. Many companies have begun to incorporate environmental issues into their development strategies, such as the use of clean energy, recycled raw materials, recyclable products, and green innovation, which will impact SME supply chains in one way or another. Therefore, this study offers several suggestions for management practices.

Firstly, given Iraq’s limited funding, SCR and AMGI strategies should be designed at the lowest possible cost, through initiatives such as reusing industrial waste or using local supplier networks to reduce dependence on unstable importers. This can be achieved by encouraging supply chain partners to collaborate and take proactive measures to prepare for future disruptions. Additionally, they can take proactive measures to address current disruptions by sharing information and promoting a culture of supply chain management. By integrating environmental issues into their strategy and formulating a compelling vision for all supply chain members, companies that adopt proactive measures to achieve SCR have shown success in managing risk.

Secondly, SMEs should not neglect AMGI and its significant role in improving EP. The AMGI model should play a pivotal role in the corporate strategy. Companies should revisit their traditional concepts and view green innovation as an important opportunity to improve their products, enhance eco-efficiency, and reduce environmental degradation. Through AMGI, companies can creatively use added resources to develop new eco-friendly products.

Finally, our findings show that EP depends on a balanced and integrated system, starting with SCR, with significant involvement from AMGI. Therefore, an integrated framework, starting with the implementation of a robust environmental management system and an incentive and penalty system for environmental protection, will foster a corporate culture that prioritizes the environment. This, in turn, will increase environmental awareness among employees and supply chain partners. Furthermore, applying green criteria to supplier choice and engaging in comprehensive collaboration with key suppliers when formulating environmental aims are crucial.

5.3. Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Research Directions

This study shows the effect of SCR on EP, which AMGI mediates. Our results reveal that SCR has a positive effect on EP in PD and RD. Furthermore, our findings show that PD does not directly impact EP but exerts an indirect influence through AMGI’s mediation, thereby validating AMGI’s role as a mediating variable. Of course, this study has some limitations because it only collects the exact data for the variables simultaneously, ignoring cross-sectional data. We should design future research based on longitudinal data tracking to examine causal relationships more closely. Future research should examine other mediating or external factors, such as moderating variables like supply chain integration [41–43].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding was received for this manuscript.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.