Factors Influencing Omega-3 Knowledge and Consumption Among Saudi Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

Background: Low consumption of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) is a significant dietary risk factor for mortality, ranking sixth globally and fourth in Middle Eastern countries. This study was to evaluate Saudi adults’ knowledge and awareness of omega-3, and to identify associated factors.

Methods: This cross-sectional survey involved 477 adults, 59% of whom were female. An online semistructured questionnaire was developed to assess participants’ omega-3 knowledge and consumption. The questionnaire consisted of three parts: participants’ demographical information, 14 questions about their knowledge and awareness of omega-3, and their main food sources of omega-3 and frequency of consumption. The questionnaire content was validated and piloted, demonstrating acceptable internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.80.

Results: The average omega-3 knowledge and awareness score was 7.5 ± 2.9 for all participants. Females had a significantly higher score than males (mean average 7.9 ± 2.6, 6.9 ± 3.4, respectively) with a mean difference 0.70 (95% CI: 0.18, 1.23; p = 0.008). Using a regression model, a negative association was found between BMI category and waist circumference, and knowledge and awareness scores (p = 0.004, P = 0.048, respectively). Conversely, education, family monthly income, and physical activity were positively associated with knowledge and awareness scores (p < 0.001, p = 0.011, P = 0.007). Omega-3 supplement consumers had a higher knowledge score compared with nonconsumers at (−1.76; 95% CI: −2.31, −1.22; p < 0.001). The oily fish and intermediate fish groups were consumed less than once/month, with only 14% of the sample meeting the recommended intake of oily fish. Barriers affecting participants’ consumption of fish were “lack of accessibility,” “cost,” and “dislike the taste or smell of fish.”

Conclusion: The findings of this study highlight the need to develop culture-specific knowledge and awareness campaigns on omega-3, particularly regarding marine sources. The study also provides insight into the barriers causing low consumption of fish that need addressing.

-

Algorithm 1: Contributions to the Literature.

-

Omega-3 index is low among Saudi adults, inadequate intake of omega-3 was found to be associated with low nutritional knowledge in general.

-

The average knowledge and awareness score of omega-3 was 7.5 out of 14 points.

-

Higher omega-3 knowledge scores were associated with older age, higher education, higher income, and the use of omega-3 supplements.

-

Only 14% of Saudi participants met the dietary recommendation of oily fish consumption.

-

Lack of easy access to fish, its cost, and its taste were reasons for not having enough fish consumption among participants.

-

Culturally appropriate campaigns are needed to increase omega-3 awareness. Additionally, barriers to fish consumption must be addressed.

1. Introduction

Suboptimal diet is a vital preventable risk factor for noncommunicable diseases. Worldwide, dietary risks were the cause of 11 million deaths among all adults in 2017, as well as 255 million disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs). Cardiovascular disease (CVD) was the leading cause of diet-related death, followed by cancers and type 2 diabetes [1]. In 2016, there were 201,300 Saudis with CVD and it accounted for over 45% of all deaths [2]. The economic burden of CVD in Saudi Arabia was estimated to be $3.5 billion and this number is estimated to triple to $9.8 billion by 2035 [2, 3], given the rise of CVD risk factors in the country such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidaemia, hypertension, and others [4].

Dietary risks were responsible for 55% of CVD [5]. Several studies have shown that individual who consumed oily fish weekly frequency had almost one-half the risk of death from CVD and almost one-third the risk of death from a heart attack comparing with nonconsumer of oily fish [6]. Studies have also demonstrated that intake of marine omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) for at least 6 months can reduce cardiovascular events by 10%, cardiac death by 9%, and coronary events by 18% [7]. A meta-analysis of 38 randomized controlled trials found that omega-3 was associated with reduced CVD mortality and its complications, with greater relive risk reductions in CVD of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) trials than those of EPA and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) [8]. Omega-3s may reduce the risk of CVD through several mechanisms, including lowering associated with risk factors such as triglycerides (TG), enhancing cell membrane stabilization, and reducing inflammation [9]. Omega-3s play an important role in brain growth and development, blood pressure regulation, blood clotting, renal function, and inflammatory and immunological reactions [9–11].

The European Food Safety Agency (EFSA) recommends a daily intake of 250 mg/d EPA and DHA for adults, as it is negatively associated with CVD risk in a dose-dependent way up to 250 mg/d (1–2 servings/week of oily fish) in healthy subjects [12]. The American Heart Association (AHA) recommends a consumption of one portion (125 g) of oily fish and one portion of lean fish at least twice a week, which results in a mean intake of 3 g/week or 430 mg/d of DHA and EPA for the general population [9].

Less than 20% of the world’s population consumes ≥250 mg/day of seafood omega-3 [13]. Low consumption of omega-3, especially EPA and DHA, is classified as the sixth major dietary risk factor of death at the global level, while in the Middle East countries, omega-3 deficiency is more prevalent and ranks as the fourth dietary risk factor [1]. Saudis adults include fish in their diets at an average of 1.4 ± 1.2 meals/week [14]. Consequently, Saudi have significantly low blood levels of omega-3 index <3.91% ± 1.4% [15], which may contribute to increased risk of CVD. Problems associated with inadequate intake of omega 3 were found to be associated with low nutritional knowledge among pregnant women. A greater degree of nutrition knowledge is widely recognized to enhance healthier dietary behaviours [16, 17], whereas a lower level is significantly associated with poor eating habits, imbalanced dietary patterns, and an increased risk of nutrition-related chronic diseases [18].

In 2024, the omega-3 world map review was updated, revealing that 92% of the available data on omega-3 status originates from European and North America countries [19]. Only two studies have assessed omega-3 awareness within the Saudi population [20, 21]. Both illustrate briefly participants’ awareness of omega-3 in adults and the other was among medical students. However, neither study investigated factors influencing people’s awareness and knowledge of omega-3 nor did they explore the types of seafood participants consumed. A study by Bailey et al. [22] emphasised the need to identify factors that influencing omega-3 intake, including cost, availability, and dietary preferences. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate Saudi adults’ knowledge and awareness of omega-3, identify its influencing factors. In addition, to determining omega-3 food sources using a brief food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) for the previous month.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

A cross-sectional survey of adults living in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia was undertaken. It was conducted during December to March 2023/2024. The sample size was calculated based on the following formula: N = z2 × P× (1−P)/e2, with a 95% confidence interval (CI); z = level of confidence (z = 1.96); p = estimated proportion of the population that presents the characteristic p = 0.5; e = margin of error (e = 0.05); The resulting sample size was 384 participants, adding a 20% attrition rate as 461 participants were required.

An online self-administered questionnaire was used to recruit participants. It was distributed through social media, personalized messages and emails. Each participant received a brief paragraph about the study, including its aim and nature, as well as their right to withdraw from the study at any time. An online consent was obtained from all participants before they participated in the study. Analytical tools were used to monitor response rates and identify any potential problems. Participants were included in the study if they were Saudi adults with online access who were willing to participate and provide informed consent. Non-Saudi individuals and those younger than 18 years old were excluded. The Ethics Committee of King Abdulaziz University’s Unit of Biomedical Ethics approved this study (reference no. 124-24).

2.2. Study Instrument

An online semistructured questionnaire was developed using national and international published questionnaires to assess omega-3 participants’ knowledge and consumption. The questionnaire consisted of three parts covering participants’ demographical information, their knowledge and awareness of omega-3, as well as their main food sources of omega-3 and frequency of consumption.

The questionnaire content was validated and culturally adapted by a panel of experts consisting of two nutritionists and one physician. Experts assessed the questionnaire for relevance, comprehensiveness, clarity, potential for bias, and the representativeness of the food items in the FFQ for Saudi seafood consumption. They also reviewed the overall knowledge score. The original questionnaire was developed in English and subsequently translated into Arabic to accommodate the native language of the study participants. To ensure semantic equivalence between the two versions, a rigorous review process was conducted to verify the consistency of meaning. Then the questionnaire was piloted among 30 participants prior to being administered among the final study sample to ensure clarity and highlight problems.

Some changes were made to certain questions to make them more understandable for lay people. For example, when participants were asked about dietary recommendation of omega-3 using grams as “250–500 mg/day,” most of the participants did not answer the question. Therefore, the panel decided to change this to “fish consumption.” The internal consistency of the questionnaire was tested using Cronbach’s alpha and the result showed an acceptable alpha of 0.80.

2.3. Assessment of Anthropometric Measurement and Lifestyle

The first part of the questionnaire included sociodemographic questions like age, gender, education, and family income. Information regarding height, weight, and waist circumference was self-reported by participants and brief instructions about how to measure waist circumference were provided. Participants’ body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the standard formula (weight (kg)/height (m2)). The resulting BMI values were categorized according to World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines: underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), normal (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2), and obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) [23]. The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) cut-offs for waist circumference were used, as they are not only gender specific but also more population specific. Thus, waist circumference >90 cm for men and >80 cm for women were considered risk factors of metabolic complications [24]. Information regarding participants’ lifestyles, such as smoking and physical activity, was collected.

2.4. Assessment of Omega-3 Knowledge and Awareness

Participants’ omega-3 knowledge and awareness were assessed using 14 questions that were developed and adapted from different published sources [21, 25–28]. Then a total score out of 14 was generated. This included collecting information regarding participants’ basic knowledge of nutrition, if lack of food diversity effects nutrient intake, dietary fat importance for health, having information about fatty acid, heard about omega-3, knowing its importance, knowing about food that is rich in omega-3, knowing that fish differ in their content of omega-3, knowing that there are animal, and plant sources of omega-3, and knowing dietary recommendations of EPA and DHA. Response options were “yes,” “no,” and “I don’t know.” Furthermore, two multiple-choice questions were asked regarding “fish that is high in omega-3” and “disease that is prevented by omega-3.” In addition, two questions had multiple choices for “sources that provide high quality of omega-3” and “recommended dietary intake of fish,” where participants had to choose only one answer.

2.5. Assessing Participants’ Food Sources of Omega-3

A brief food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) was developed were participants selected foods that are considered sources of omega-3. Food lists were selected from different studies [29–31] and based on food availability in the Saudi market and whether it is among the most commonly consumed food by Saudis (unpublished source). Fish was grouped based on its content of omega-3: oily fish & high in DHA&EPA (>1000 mg/100 g); intermediate fish & intermediate levels of DHA&EPA (500–1000 mg/100 g); White (nonoily) fish & only containing lower levels of EPA & DHA 0–500 mg/100 g [32, 33], and other food sources. For each food item, participants estimated the total number of servings consumed over the previous month.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was undertaken using Stata statistical software release 12 (Stata Corporation) [34]. Descriptive statistics means and standard deviation (SD) were used to describe continued data of the general characteristics of the whole sample and after being stratified by gender. For categorical data, numbers and proportion were used to describe participants. A Pearson chi-square test was used to test the differences in the proportion by gender in terms of general characteristics, such as BMI, social status, and education. For continuous variables like age and waist circumference, an independent two-sample t-test (a two-tailed test) was used. To calculate a knowledge and awareness score, a score of one was assigned for every correct answer (correct answers to questions were “yes”) and a score of zero was assigned for a wrong answer.

For multiple-choice questions, a quarter point was assigned for each correct selection, to obtain a whole number in the total score and to fairly differentiate between participants who knows more correct answers for the same questions than others. The total knowledge and awareness score was then calculated for each participant, ranging from 0 to 14. A Pearson’s chi-square test was used to determine the association between gender and proportions of knowledge and awareness. A regression model adjusted for gender and age was used to investigate factors affecting participants’ knowledge and awareness of omega-3. Last, p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

Table 1 illustrates participants’ general characteristics as a total number and after being stratified by gender. A total of 477 adults participated in the study (59% female, 41% male). The average age of participants was 30.5 ± 10.8 years old. The average age for females was 31 ± 11 years old and the average age for males was 29.6 ± 10.2. The mean of waist circumference and BMI was significantly lower among females than males, with mean differences −7.4 cm (95%CI: −5.5, −9.3; p < 0.001) and −1.9 kg/m2 (95% CI: −0.80, −3.1; p < 0.001), respectively. The study found that 56.8% of the study participants were single, 55.6% had a bachelor degree, and 38.4% of them had less than 5999 riyal/month family income. Among the study participants, 76.5% were nonsmokers. Regarding physical activity, 29.9% of participants reported engaging in regular physical activity (≥4 times per week), while 29% engaged in exercise only once per week. There were significant differences between males and females in terms of their social status (p < 0.001), family income (p = 0.024), smoking (p < 0.001) and physical activity (p = 0.036).

| General characteristics | All participants (n = 477) | Females (n = 282) | Males (n = 195) | p value† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Age (years) (mean ± SD) ∗ | 30.50 | 10.8 | 31.1 | 11.2 | 29.6 | 10.2 | 0.126 |

| Height (cm) (mean ± SD) ∗ | 163.9 | 9.5 | 158.9 | 6.2 | 171.2 | 8.8 | <0.001 |

| Weight (kg) (mean ± SD) ∗ | 71.2 | 19.1 | 64.6 | 15.9 | 80.7 | 19.1 | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 77.8 | 10.9 | 74.8 | 9.6 | 82.2 | 11.1 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (mean ± SD) ∗ | 26.4 | 6.2 | 25.6 | 6.1 | 27.5 | 6.1 | 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||||

| Normal weight | 218 | 45.7 | 151 | 53.6 | 67 | 34.4 | — |

| Overweight | 141 | 29.6 | 70 | 24.8 | 71 | 36.4 | — |

| Obese | 118 | 24.7 | 61 | 21.6 | 57 | 29.2 | <0.001 |

| Social statues | |||||||

| Single | 271 | 56.8 | 170 | 60.3 | 101 | 51.8 | — |

| Mired | 180 | 37.7 | 88 | 31.2 | 92 | 47.2 | — |

| Divorce | 26 | 5.5 | 20 | 7.1 | 6 | 3.1 | <0.001 |

| Education | |||||||

| Diploma | 18 | 3.8 | 10 | 3.6 | 8 | 4.1 | — |

| High school | 158 | 33.1 | 80 | 28.4 | 78 | 40 | — |

| Bachelor degree | 265 | 55.6 | 170 | 60.3 | 95 | 48.7 | — |

| Postgraduate degree | 36 | 7.6 | 22 | 7.8 | 14 | 7.2 | 0.054 |

| Economic statues (for family) | |||||||

| Less than 5999 riyal | 183 | 38.4 | 121 | 42.9 | 62 | 31.8 | — |

| 6000–10,999 riyal | 131 | 27.5 | 71 | 25.2 | 60 | 30.8 | — |

| 11,000–15,999 riyal | 64 | 13.4 | 41 | 14.5 | 23 | 11.8 | — |

| 16,000–20,999 riyal | 50 | 10.5 | 28 | 9.9 | 22 | 11.3 | — |

| More than 21,000 riyal | 49 | 10.3 | 21 | 7.5 | 28 | 14.4 | 0.024 |

| Smoking statues | |||||||

| Smoker (yes) | 78 | 16.4 | 29 | 10.3 | 49 | 25.1 | — |

| Former smoker | 34 | 7.1 | 8 | 2.8 | 26 | 13.3 | <0.001 |

| Physical activity | |||||||

| Never | 79 | 16.6 | 49 | 17.4 | 30 | 15.4 | — |

| Once a week | 139 | 29.1 | 96 | 34.0 | 43 | 22.1 | — |

| Twice a week | 82 | 17.2 | 43 | 15.1 | 39 | 20 | — |

| Three times a week | 34 | 7.1 | 19 | 6.7 | 15 | 7.7 | — |

| More than four times week | 143 | 29.9 | 75 | 26.6 | 68 | 34.9 | 0.036 |

- ∗Differences between genders were assessed by using an independent sample t-test.

- †Significant differences between the proportion of males and females in other variables have been assessed using a chi2 test.

3.2. Assessment of Omega-3 Knowledge and Awareness

The results showed that study participants had basic knowledge of nutrition and recognized that a lack of food diversity leads to a lack of nutrient intake, as well as knowing that dietary fat is important for health (73%, 86.6%, and 75.5%, respectively). However, only 41.9% of them had knowledge about types of fatty acid. Although 84% of the sample had heard about omega-3 and 80.7% knew its importance for health, 55.9% of the total sample recognized that fish differ in their content of omega-3 and 57.7% knew that there are animal and plant sources of omega-3. Only 29% of participants understood that animal sources provide a high quality of omega-3.

Salmon was the top oily fish known by participants to be high in omega-3 at 81.6%, followed by sardines at 57%, while a low number of participants knew that mackerel and herring are oily fish and considered good sources of omega-3. A low number of participants knew that disease can be prevented by omega-3 and only 57% of participants knew that omega-3 can reduce risk of cardiovascular disease, followed by infections, cholesterol, obesity, and blood pressure (43%, 35%, and 27.5%, respectively). Furthermore, 54% of participants did not know the recommended intake of fish consumption.

The average knowledge and awareness score of omega-3 was 7.5 ± 2.9 for all participants and females had significantly higher knowledge and awareness of omega-3 than males (mean average 7.9 ± 2.6, 6.9 ± 3.4, respectively, and mean differences 0.70 (95% CI: 0.18, 1.23; p = 0.008)). Generally, females gave significantly more correct answers than males (Table 2).

| Knowledge and awareness of omega-3 | All participants (n = 477) | Females (n = 282) | Males (n = 195) | p value† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| 1. Having basic knowledge about nutrition (yes) | 349 | 73.2 | 224 | 79.4 | 125 | 64.1 | <0.001 |

| 2. Lack of food diversity lead to a lack of nutrients (yes) | 412 | 86.6 | 255 | 90.8 | 157 | 80.5 | 0.005 |

| 3. Some dietary fats are important for health (yes) | 360 | 75.5 | 222 | 78.7 | 138 | 70.8 | 0.127 |

| 4. Having knowledge about different type of fatty acid (yes) | 200 | 41.9 | 124 | 43.9 | 76 | 38.9 | 0.460 |

| 5. Heard about omega-3 PUF (yes) | 402 | 84.3 | 253 | 89.7 | 149 | 76.4 | <0.001 |

| 6. Omega-3 is important for health (yes) | 385 | 80.7 | 242 | 85.8 | 143 | 73.3 | 0.002 |

| 7. Knowing food that is rich in omega-3 (yes) | 330 | 69.2 | 217 | 76.9 | 113 | 57.9 | <0.001 |

| 8. Knowing that fish differ in their content of omega 3 (yes) | 267 | 55.9 | 159 | 56.4 | 108 | 55.4 | 0.868 |

| 9. Knowing that there is three main omega-3 (ALA, EPA, and DHA) (yes) | 275 | 57.7 | 178 | 63.1 | 97 | 49.7 | 0.013 |

| 10. Witch forms provide high quality of omega-3 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.788 |

| - EPA and DHA which mainly in marine sources (yes) | 139 | 29.4 | 80 | 28.6 | 59 | 30.6 | |

| - ALA which mainly in plant sources | 44 | 9.2 | 29 | 10.4 | 15 | 7.8 | |

| - Both have same value | 163 | 34.2 | 95 | 33.9 | 68 | 35.2 | |

| - I don’t know | 127 | 26.6 | 76 | 27.1 | 51 | 26.4 | |

| 11. Fish that is high in omega-3 | |||||||

| - Sardines | 273 | 57.2 | 155 | 54.9 | 118 | 60.5 | 0.464 |

| - Tuna | 280 | 58.7 | 173 | 61.4 | 107 | 54.9 | 0.158 |

| - Salmon | 389 | 81.6 | 238 | 84.4 | 151 | 77.4 | 0.050 |

| - Mackerels | 77 | 16.1 | 34 | 12.1 | 43 | 22.1 | 0.006 |

| - Sea bass | 36 | 7.6 | 19 | 6.7 | 17 | 8.7 | 0.421 |

| - Herring | 21 | 4.4 | 13 | 4.6 | 8 | 4.1 | 0.791 |

| - Cod | 27 | 5.7 | 22 | 7.8 | 5 | 2.6 | 0.015 |

| 12. Disease that is prevented by omega-3 | |||||||

| - Cardiovascular disease | 274 | 57.4 | 194 | 68.8 | 80 | 41.1 | <0.001 |

| - Obesity | 131 | 27.5 | 86 | 30.5 | 45 | 23.1 | 0.074 |

| - Mental health (Alzheimer’s) | 206 | 43.2 | 132 | 46.8 | 74 | 37.9 | 0.050 |

| - Inflammation | 32 | 6.7 | 19 | 6.4 | 13 | 6.7 | 0.976 |

| - Cholesterol | 167 | 35.1 | 95 | 33.7 | 72 | 36.9 | 0.466 |

| - Blood pressure | 114 | 23.9 | 66 | 23.4 | 48 | 24.6 | 0.760 |

| - Dry eyes and infections | 48 | 10.1 | 21 | 7.5 | 27 | 13.9 | 0.022 |

| - Immunity system | 29 | 6.1 | 16 | 5.7 | 14 | 7.2 | 0.325 |

| 13. Knowing recommendation of EPA & DHA (yes) | 75 | 15.7 | 44 | 15.6 | 31 | 15.9 | 0.931 |

| 14. Knowing recommendation of fish intake | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.857 |

| - One portion of fish/week | 104 | 22.7 | 65 | 23.5 | 39 | 21.6 | |

| - 2 portions of fish/week, one of which is oily | 92 | 20.1 | 52 | 18.8 | 40 | 22.1 | |

| - 2–3 portion/week, one of which is oily | 24 | 5.2 | 14 | 5.1 | 10 | 5.5 | |

| - Do not know | 257 | 53.9 | 151 | 53.6 | 106 | 54.4 | |

| Average knowledge score (14) ∗ | 7.5 | 2.9 | 7.9 | 2.6 | 6.9 | 3.4 | <0.001 |

- ∗Differences between genders were assessed by using an independent sample t-test.

- †Significant differences between the proportion of males and females in other variables have been assessed using a chi2 test.

3.3. Factors Affecting Participants’ Knowledge and Awareness of Omega-3

Table 3 illustrates factors influencing participants’ knowledge and awareness of omega-3. The older age group of adults had higher knowledge than younger adults, with mean differences: 0.86 (95% CI: 0.31, 1.41; p = 0.002). There were negative associations between participants’ BMI category and waist circumference and their knowledge and awareness score (p = 0.004, p = 0.048, respectively). Participants’ education, family monthly income, and physical activity were associated with participants’ knowledge and awareness score (p < 0.001, p = 0.011, p = 0.007, respectively).

| Factors | Average knowledge score | Changes in knowledge score | 95% CI | p† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 477) | ||||||

| N | Mean | SE | ||||

| Gender (mean) | ||||||

| Male | 195 | 6.9 | 3.4 | — | — | — |

| Female | 282 | 7.9 | 2.6 | 0.70 | 0.18, 1.23 | 0.008 |

| Age group | ||||||

| 18–29 years | 291 | 7.1 | 3.1 | — | — | — |

| 30–45 years | 186 | 8.1 | 2.8 | 0.86 | 0.31, 1.41 | 0.002 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||

| Normal weight | 218 | 7.79 | 2.87 | 1 | — | — |

| Overweight | 141 | 7.32 | 3.16 | −0.79 | −1.44, −0.14 | — |

| Obese | 118 | 7.07 | 2.94 | −1.09 | −1.77, −0.40 | 0.004 |

| Waist circumference WC (cm) | ||||||

| WC acceptable | 374 | 7.6 | 2.9 | 1 | — | — |

| WC increased risk of metabolic complications | 103 | 7.1 | 3.0 | −0.64 | −1.28, −0.10 | 0.048 |

| Education level | ||||||

| Diploma | 18 | 4.3 | 2.8 | 1 | — | — |

| High school and lower | 158 | 6.4 | 3.3 | 2.1 | 0.76, 3.46 | — |

| University | 265 | 8.2 | 2.6 | 3.7 | 2.33, 4.99 | — |

| Post graduate | 36 | 8.2 | 2.5 | 3.5 | 1.82, 4.99 | <0.001 |

| Economic statues (for family) | ||||||

| Less than 5999 riyal | 183 | 7.14 | 3.04 | 1 | — | — |

| 6000–10,999 riyal | 131 | 7.14 | 3.10 | −0.12 | −0.78, 0.54 | — |

| 11,000–15,999 riyal | 64 | 7.96 | 3.02 | 0.66 | −0.17, 1.49 | — |

| 16,000–20,999 riyal | 50 | 7.84 | 2.41 | 0.51 | −0.41, 1.43 | — |

| More than 21,000 riyal | 49 | 8.64 | 2.65 | 1.43 | 0.49, 2.36 | 0.011 |

| Physical activity | ||||||

| Never | 79 | 6.89 | 3.3 | 1 | — | — |

| Once a week | 139 | 7.33 | 3.02 | 0.26 | −0.54, 1.05 | — |

| Twice a week | 82 | 7.08 | 2.89 | 0.06 | −0.84,0.96 | — |

| Three times a week | 34 | 7.79 | 3.06 | 0.84 | −0.32,2.01 | — |

| More than four times week | 143 | 8.09 | 2.74 | 1.19 | 0.39, 1.99 | 0.007 |

| Eating fish generally | ||||||

| Yes, always | 301 | 7.73 | 2.89 | 1 | — | — |

| Yes, sometimes | 116 | 7.07 | 3.23 | −0.482 | −1.12, 0.144 | — |

| Not eating fish | 92 | 6.95 | 2.84 | −0.693 | −1.57, 0.182 | 0.152 |

| Consuming omega-3 supplements | ||||||

| Yes | 153 | 8.79 | 2.52 | 1 | — | — |

| No | 324 | 6.85 | 2.99 | −1.76 | −2.31, −1.22 | <0.001 |

- †Age and sex adjusted regression model −1.

Participants who always eat fish had a higher knowledge score (7.7 ± 2.9) regarding omega-3 compared with participants’ who sometimes consume fish or do not eat fish at all (7.1 ± 3.2 and 6.95 ± 2.8, respectively); however, the differences are not significant (p = 0.152). When participants (data not shown) were asked regarding reasons for not eating fish at all or less frequently, 10% of them mentioned it was due to “having an allergy,” 57% of them mentioned “lack of accessibility,” 54% stated “cost,” and 46% said they “do not like the taste or smell of fish.”

Participants who had heard about omega-3 mentioned that their source of information was mainly their friends (31%), followed by doctors (24.9%) and social media (21%). Only 5% mentioned an educational entity. There was a significant association between the source of education and participants’ score of knowledge and awareness (p = 0.005). Furthermore, participants’ who consumed omega-3 supplements had higher knowledge and awareness compared with participants who do not consume omega-3 supplements, with a mean difference of −1.76 (95% CI: −2.31, −1.22; p < 0.001).

3.4. Brief Food Frequency Questionnaire of Omega-3

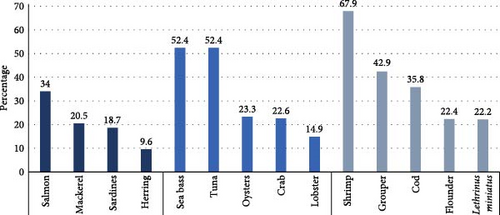

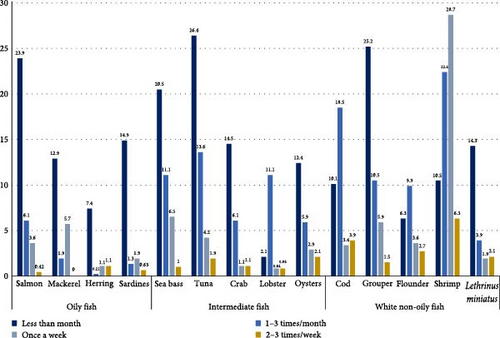

Table 4 illustrates the brief FFQ for the previous month in relation to all participants and compares the differences in the FFQ by gender. Salmon was considered the most commonly consumed food in the oily fish group, followed by mackerel and then sardines (34%, 20.5%, and 18.7%, respectively). Among participants who consumed oily fish less than once a month, there were significant gender differences in the frequency of mackerel and sardines consumption (p = 0.014 and 0.021, respectively).

| Food items | Frequency of consumption food items | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Less than/month | 1–3 times/month | Once a week | 2–3 times/week | 4–5 times/week | p Value dif between gender | |

| Oily fish | |||||||

| Salmon | 162 (34%) | 114 (23.9) | 29 (6.1) | 17 (3.6) | 2 (0.42) | — | 0.174 |

| Mackerel | 98 (20.5) | 62 (12.9) | 9 (1.9) | 27 (5.7) | — | — | 0.014 |

| Herring | 46 (9.6) | 35 (7.4) | 1 (0.21) | 5 (1.1) | 5 (1.1) | — | 0.275 |

| Sardines | 89 (18.7) | 71 (14.9) | 6 (1.3) | 9 (1.9) | 3 (0.63) | — | 0.021 |

| Intermediate | |||||||

| Sea bass | 250 (52.4) | 98 (20.5) | 53 (11.1) | 31 (6.5) | 5 (1.0) | — | 0.531 |

| Tuna | 250 (52.4) | 126 (26.4) | 65 (13.6) | 20 (4.2) | 9 (1.9) | — | 0.108 |

| Crab | 108 (22.6) | 69 (14.5) | 29 (6.1) | 5 (1.1) | 5 (1.1) | — | 0.342 |

| Lobster | 71 (14.9) | 10 (2.1) | 53 (11.1) | 4 (0.84) | 4 (0.84) | — | 0.175 |

| Oysters | 111 (23.3) | 59 (12.4) | 28 (5.9) | 14 (2.9) | 10 (2.1) | — | 0.930 |

| White nonoily fish | |||||||

| Cod | 171 (35.8) | 48 (10.1) | 88 (18.5) | 16 (3.4) | 19 (3.9) | — | 0.325 |

| Grouper | 205 (42.9) | 120 (25.2) | 50 (10.5) | 28 (5.9) | 7 (1.5) | — | 0.147 |

| Flounder | 107 (22.4) | 30 (6.3) | 47 (9.9) | 17 (3.6) | 13 (2.7) | — | 0.254 |

| Shrimp | 324 (67.9) | 50 (10.5) | 107 (22.4) | 137 (28.7) | 30 (6.3) | — | 0.404 |

| Lethrinus miniatus | 106 (22.2) | 68 (14.3) | 19 (3.9) | 9 (1.9) | 10 (2.1) | — | 0.173 |

| Other sources of omega-3 | |||||||

| Meat | 301 (63.1) | 138 (28.9) | 44 (9.2) | 75 (15.7) | 24 (5.1) | 50 (10.5) | 0.050 |

| Egg | 411 (86.2) | 118 (24.7) | 41 (8.6) | 102 (21.4) | 55 (11.5) | 95 (11.5) | 0.355 |

| Beans | 342 (71.9) | 147 (30.8) | 21 (4.4) | 34 (7.1) | 40 (8.4) | 82 (17.2) | 0.299 |

| Soya beans | 100 (20.9) | 71 (14.9) | 9 (1.9) | 20 (4.2) | — | — | 0.411 |

| Olive oil | 429 (89.9) | 113 (23.7) | 59 (12.4) | 92 (19.3) | 65 (13.6) | 100 (20.9) | 0.024 |

| Flax seeds | 187 (39.2) | 41 (8.6) | 119 (24.9) | 10 (2.1) | 17 (3.6) | — | 0.448 |

| Shia seeds | 205 (42.9) | 98 (20.6) | 52 (10.9) | 30 (6.3) | 8 (1.7) | 17 (3.6) | 0.531 |

| Dairy | 413 (86.6) | 18 (3.8) | 12 (2.5) | 50 (10.5) | 125 (26.2) | 208 (43.6) | 0.174 |

| Avocado | 258 (54.1) | 119 (24.9) | 59 (12.4) | 27 (5.7) | 19 (3.9) | 34 (7.1) | 0.253 |

| Nuts | 307 (64.4) | 12 (2.5) | 36 (7.6) | 54 (11.3) | 29 (6.1) | 39 (8.2) | 0.562 |

For intermediate omega-3 fish sources, sea bass and tuna were the most frequently consumed (52.4% each), followed by oysters (23.3%) and crab (22.6%). Consumption frequency ranged from less than once a month to 1–3 times a month, with no significant gender differences. Similarly, in the white nonoily fish group, shrimp, grouper, and cod were the most consumed, and there were significant differences between genders in terms of the frequency of consumption of olive oil and meat (p = 0.024 and 0.05, respectively) (Figures 1 and 2).

4. Discussion

Although omega-3 fatty acids are critical for the maintenance of overall health, awareness, and knowledge of their benefits exhibit significant variability across diverse populations and are subject to numerous influencing factors. This study was to evaluate Saudi adults’ knowledge and awareness of omega-3 and factors associated with it. The mean knowledge and awareness score of omega-3 was 7.5 ± 2.9 out of 14 points, with females exhibiting substantially more knowledge and awareness than males. Generally, females had significantly more correct answers than males. Belonging to the older age group, higher education, higher income level, and use of omega-3 supplement were all significantly associated with a greater knowledge and awareness score regarding omega-3. Participants who always eat fish had a higher knowledge score (7.7 ± 2.9) compared with participants who sometimes eat fish or do not eat fish at all, but these differences were not significant. “Salmon and sardines” were the most common oily fish consumed by participants, as well as “sea bass, tuna and oysters” from the intermediate class, although their frequency of consumption was relatively low at “less than once/month” compared with white- nonoily fish. Only 14% of the sample met the dietary recommendation for oily fish.

Nutritional knowledge influences dietary behaviours and eating habits, as a higher level of nutritional knowledge contributes to promoting a healthier dietary intake [16, 17, 35]. In this study, the average knowledge score regarding omega-3 was moderate and females had a higher score than males (mean difference 0.7; 95% CI: 0.18, 1.23). A study conducted among 834 young Canadian adults (aged 18–25 years old) found that only 70% of the participants had heard of omega-3 and had only limited information about it [26]. While in the US adults, saturated fatty acid was the most recognised type of fat and only half of those surveyed had heard about omega-3 [36]. Only 40.5% of Canadian participants had heard of omega-3 terminology ALA and 51.3% had heard of EPA as an abbreviation compared with full names [26]. Other US and German study found that more than half of the participants believed that omega-3 was beneficial for heart and brain health [37].

Similarly, a study in Saudi Arabia found that 51.6% of male participants had not heard of omega-3, while 88% of females had heard about it, and another study found that 61.3% of participants had not heard of omega-3 at all [21]. The difference in omega-3 knowledge between genders could be attributed to significant variations in their demographic data, including BMI and WC, both showed negative association with participants’ knowledge. This in line with a study conducted among Saudi young adults, where females demonstrated greater knowledge of calorie food labels, a result attributed to disparities in respondents’ social characteristics [38].

Currently, there is no consensus on recommendations related to omega-3, especially EPA and DHA. Therefore, recommendations regarding fish intake were assessed in this study. It was found that more than half of this study’s participants (54%) did not know the dietary recommendation of fish intake; only 25% of participants correctly recognized the dietary recommendation. Among 854 Australian adults, 21% of participants consumed oily fish two times/week [39]. A limited number of participants (30% of US and 24% of German individuals) believed that they consume adequate amounts of omega-3 from their diet [37]. Many studies mention that the cost of fish is an important barrier to the consumption of fish and seafood [39–41]. This is in line with the current study’s findings, as 46% of participants mentioned cost as an obstacle to fish consumption. Other studies have found inconvenience and taste as barriers to consumption among older European adults [42]. In another study, among 2910 participants, it was found that the most appropriate approach to promote fish consumption was lowering the price and enhancing its availability in stores [43].

There are many factors influencing people’s knowledge and awareness of omega-3, as found in this study. A study conducted among pregnant women (n 190) found that women with higher levels of education and income were more aware of fish consumption and the importance of omega-3 for health [28]. Another study suggested that being female and having a higher level of education were significantly associated with higher levels of consumer awareness and knowledge regarding trans fatty acid [44]. Similarly, studies have found that males have a lower level of nutrition knowledge than females, and income and normal weight are linked to an increased knowledge and awareness of trans fatty acid [44].

Furthermore, a large-scale cross-sectional study among Wuhan residents found that participants aged 35–44 (23.3%), females (22.8%), those having a master’s degree or above (34.1%), and those without a history of chronic disease (24.6%) were more likely to have higher awareness rates than others (all p < 0.001) [35]. One study reported that for every one point increase in health literacy, there was a 21% point increase in the US Department of Agriculture Healthy Eating Index score [45]. An across focus group study found that several factors influenced the type and frequency of seafood consumption in a household, such as cost, freshness, availability, confidence in meal preparation, and family preference [46]. Regarding sources of information about omega-3, similar to our findings, participants in one study declared that they got their information mostly from friends and relatives [43].

In this study, no association was found between a participant’s knowledge of omega-3 dietary sources and their general fish consumption. However, a significant association was observed between omega-3 knowledge and the use of omega-3 supplements. This suggests that while knowledge of dietary sources may not directly translate to increased fish consumption, it does correlate with supplement adherence. Similarly, average omega-3 index concentrations did not significantly differ with dietary knowledge and perception. This is consistent with findings from other studies, such as those conducted in German and US participant groups, where 26% and 10% respectively believed that dietary supplements were needed [37], highlighting a potential disconnect between knowledge of dietary sources and reliance on supplements. Another study found that 45% of individuals in the US and 24% of individuals in Germany reported using omega-3 supplements [22]. Omega-3 dietary supplements are the third most common product choice in the US [47].

Dietary intake of EPA and DHA is the single predictor of blood levels of EPA and DHA. In the global map of omega-3, which was updated in 2024, there is a similarity between intake of marine omega-3 and omega-3 status; generally in Middle East countries EPA and DHA intake and status is very low [19]. Although participants’ main oily fish consumption comprised “salmon and sardines,” as well as “sea bass, tuna and oysters” in the intermediate fish category, the frequency of their consumption was less than once/month, which reflects a low dietary intake of omega-3. In the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), data showed that only 20% of consumed seafood comprised oily fish [48], and 21% of Australian participants consumed oily fish two times/week [39]. Another study found that Saudi people consumed an average of 1.4 ± 1.2 fish meals/week at home [14], which is similar to the current study’s findings, where participants consumed white nonoily fish more frequently than oily fish.

The present study has notable limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. This study’s assessment did not account for assessing dietary intake of EPA and DHA, as this is difficult due to a lack of detailed information on fish consumption among Saudis, and missing information on EPA and DHA levels in the fish mainly consumed in Saudi Arabia. Therefore, information regarding fish that is mainly consumed by the study sample was collected to allow for future work and analysis of its content of omega-3. In addition, the questionnaire was self-reported by participants and so may not accurately reflect actual practices. Despite the limitations, this study used a good sample size and content validity. Although a higher number of females were recruited than males, and there is a well-known bias in terms of gender and nutritional knowledge [49], the regression model was adjusted for gender and BMI to minimise this bias. Also, a score was developed to assess factors influencing participants’ knowledge of omega-3 and whether this knowledge affected fish consumption.

Future research may need to account for the factors that can influence omega-3 index values and consumption. Findings presented in this study identified multiple barriers to omega-3 consumption which need to be overcome by increasing knowledge and awareness among Saudi adults regarding omega-3, particularly EPA and DHA, dietary recommendations of EPA and DHA, and best dietary sources available in Saudi Arabia. We recommend implementing targeted public health campaigns using diverse media platforms to disseminate accurate information about omega-3 benefits and natural sources. Additionally, educational programs in schools and community centers, tailored to different age groups and genders, can promote long-term dietary changes. Providing practical cooking demonstrations and recipes that incorporate local omega-3-rich foods, such as seafood from the Red Sea and Arabian Gulf, can also enhance consumption. Furthermore, structural environmental changes such as enhancing consumer accessibility to good quality of oily fish or enriching chicken meat and eggs with DHA as (as this has led to a notable increase in the omega-3 index [50]) are needed. A multifaceted approach is essential to increase omega-3 consumption.

5. Conclusions

This study found that participants had a low level of knowledge and awareness of omega-3. Factors such as education, income, BMI, WC, physical activity, and omega-3 supplements use were significantly associated with participants’ knowledge. Oily fish consumption was low among study participants, which may affect overall health and well-being and potentially contribute to increased health care costs and reduced quality of life.

These results should inform future nutritional interventions aimed at improving people’s knowledge and consumption of omega-3 fatty acids, particularly EPA and DHA from natural sources, to avoid an over-reliance on supplements. It is essential to implement effective strategies such as public health campaigns (e.g., as organizing seafood festivals or showcasing traditional Saudi dishes adapted to include omega-3-rich ingredients, involving local communities in the planning and implementation of campaigns to ensure relevance and effectiveness.), educational programs, and social media initiatives to raise awareness about the importance of omega-3 s, their sources, and dietary recommendations. Addressing barriers such as cost, availability, and taste preferences can promote wider adoption of omega-3-rich foods. The health of the Saudi population depends on swift and impactful action.

Ethics Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the King Abdulaziz University, Unit of Biomedical Ethics (Ethic reference: 124-24).

Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Disclosure

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Nothing to declare.

Funding

This research was funded by the research work was funded by Institutional Fund Projects under Grant No. IFPIP: 465-253-1443), the author greatly acknowledge technical and financial support provided by the Ministry of Education and King Abdulaziz University, DSR, Jeddah Saudi Arabia.

Acknowledgments

The authors specially thank the nutritionist’s help in distributing the questionnaires.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

All research data related to this project can be found in the DSR at King Abdul-Aziz University.