The Shield of Resilience: Mediating the Effects of Internet Addiction on Adolescent Anger Control

Abstract

Adolescence is a crucial developmental period characterized by physical, emotional, and social changes. This makes adolescents particularly vulnerable to various stressors, including Internet addiction. The increasing prevalence of Internet use has brought new challenges, as excessive and uncontrolled engagement with digital platforms, often referred to as Internet addiction, can disrupt emotional regulation and increase behavioral difficulties. Anger control, an important component of emotional wellbeing at this stage, is particularly affected by Internet addiction and can lead to aggressive tendencies and long-term emotional problems. This study examines the mediating role of psychological resilience in the relationship between Internet addiction and anger control among adolescents between the ages of 12 and 14. A total of 406 students, selected using convenience sampling, participated in the study. Data were collected from the Internet Addiction Test (IAT), the Trait Anger and Anger Expression (T-Anger and AngerEX) scale, and the Child and Youth Resilience Measure (CYRM-12). Statistical analyses, including regression and mediation analyses, were conducted using the PROCESS macro in SPSS with 5000 bootstrap samples. The results show a significant negative relationship between Internet addiction and both psychological resilience and anger control, with Internet addiction explaining 20.2% of the variance in resilience and 11.5% in anger control. In addition, psychological resilience partially mediated the relationship between Internet addiction on anger control, explaining 25.1% of the variance. These findings highlight the importance of enhancing psychological resilience as a protective factor to mitigate the negative impact of Internet addiction on adolescents’ emotional regulation.

1. Introduction

Adolescence is a crucial period for both physical and cognitive development, holding significant importance in human lives [1]. Rapid and crucial changes in body, mind, and social interactions significantly impact overall physical and psychological well-being during this stage of life [2]. Adolescence is often seen as a time of stress and turmoil, and studies have shown that during this developmental stage, people are particularly vulnerable to a wide range of stressors [3]. Fast physical growth and maturation are two of the most notable changes during adolescence. Adolescents gain significant height and weight and develop sexual characteristics. This physical development is accompanied by several cognitive changes, including improvements in abstract reasoning, problem-solving, and decision-making skills [4, 5].

Adolescents also experience significant socioemotional changes during this developmental period [6]. They begin to experience a sense of identity and independence, and their relationships with peers and adults become increasingly important [7]. Therefore, individuals going through this life stage often experience intense emotional turmoil and struggle with issues such as self-esteem, anxiety, and depression [8–10]. Moreover, adolescence is a period of increased risk-taking behavior and experimentation, which can have both positive and negative consequences for overall well-being [11, 12].

It is not uncommon for adolescents to be prone to developing various negative coping mechanisms during this phase in an attempt to understand their mental states through them [13, 14]. These negative coping mechanisms may lead to behaviors such as substance abuse, self-harm, procrastination, and withdrawal [15–17]. Furthermore, they can have long-term negative effects on their physical and mental health [18, 19]. In the 21st century, when technology has become a crucial part of human life, the use of the Internet has been included among these coping mechanisms [20–22]. Internet becoming a coping mechanism for individuals also leads to various negative outcomes. For instance, “Internet addiction” is defined as excessive usage or overly limited control of the latter, in such a way that it occupies the daily life of the individual and causes problems [23]. In 18.3% of adolescents, who developed addiction due to unhealthy Internet use, problems related to academic achievement, interpersonal relationships, decrease in self-confidence and participation in society, self-isolation, or restriction were observed [24]. Moreover, adolescents are known to experience their emotions at extremes and to be deeply affected by these feelings. One of the emotions affected by Internet addiction in adolescents is anger. Many studies in the literature have shown that adolescents with Internet addiction show more aggressive tendencies than nonaddicted peers [25, 26]. These results are similar to various other types of addiction in regard to aggressive behavior [27–30]. Moreover, the relationship between anger control and aggressive behavior has also been acknowledged in empirical studies [31, 32]. Anger, which cannot be managed well in adolescence period, becomes excessive or suppressed and may be replaced by more negative and destructive emotions in the following years [33]. However, unsuppressed anger may not prevent the tendency to such hostile and destructive emotions. In this respect, knowing how the transmission of anger is correctly managed seems extremely important for this age group.

Psychological resilience refers to the ability of children to overcome various challenges and harsh experiences. It involves demonstrating adaptability to extreme events [34]. Richardson [35] identified key factors that contribute to the enhancement of psychological resilience. These factors include exposure to situations that are critical and risky for the individual, the presence of supportive mechanisms, and the individual’s responses to complex and ongoing situations and difficulties. However, Benard [36] identified three promoting factors that contribute to the development of psychological resilience in adolescents. These factors include Interest, positive expectations, and participation opportunities. Psychological resilience can influence the way individuals experience their lives in both adults and adolescents in order to significantly change the quality of life [37]. Additionally, the relationship between psychological resilience and many psychological conditions (anxiety, depression, stress, etc.) has been revealed by studies in the literature [38–41]. For instance, Philippou [42] reported the impact of psychological resilience in reducing anxiety in people with certain inflammatory diseases. In addition, O’Rourke et al. [43] highlighted that psychological resilience may serve as a predictor of depressive symptoms in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Moreover, some of these studies also mention the relationship between psychological resilience and Internet addiction, or psychological resilience and anger control [44, 45].

Despite the increasing prevalence of Internet addiction among adolescents, the majority of previous studies have focused mainly on its direct psychological and behavioral effects, such as emotional dysfunction and aggressive behavior [25, 46, 47]. In addition, as the adolescent population increases, the negative effects of certain types of Internet use, such as social media and online gaming, are becoming more obvious [48, 49]. Furthermore, anger, a dominant emotion during adolescence, often leads to difficulties in processing and coping with situations. As adolescents develop different ways of coping, many studies show that Internet use has become a key component in their emotional regulation [50–52]. It is well known that coping strategies developed during adolescence can have lasting effects throughout life [53]. However, the underlying mechanisms that either increase or decrease the impact of Internet addiction, particularly in terms of anger control, remain underexplored. In this context, psychological resilience, recognized as a protective factor, plays a crucial role in helping individuals adapt to stress and adversity and should not be overlooked. By supporting emotional regulation and promoting healthier coping mechanisms, psychological resilience may also help to regulate negative emotions such as anger. Understanding its role in this context could provide crucial insights for the development of more targeted interventions for adolescents.

Overall, when considering the relationship between all variables, Internet addiction has been associated with several negative psychological outcomes, including emotional dysregulation and difficulty controlling anger. Psychological resilience, as a protective factor, may mitigate these negative effects by promoting adaptive coping strategies and emotional balance. While anger control is crucial for adolescents’ emotional well-being, excessive Internet use may decrease this ability, leading to increased emotional reactivity and aggressive tendencies. The interplay between these variables suggests that psychological resilience may mediate the effects of Internet addiction on anger control.

This study aims to examine the mediating role of psychological resilience in the effect of Internet addiction on anger control in adolescents. When the relevant literature is examined, it is seen that the studies concerning the mediating variables in the relationship between Internet addiction and anger control for adolescents are quite limited. Examining the role of psychological resilience in this relationship will, therefore, significantly contribute to the literature. In addition, it is known that anger management is a major problem in adolescents and they need this support in navigating this issue is advised [54, 55]. This study will provide a more accurate view on how to better support these individuals.

1.1. Hypotheses Development

We formulated and evaluated four hypotheses using cross-sectional and exploratory research designs, informed by existing literature, to meet the objectives of our study. Numerous studies on Internet addiction have demonstrated that this phenomenon is linked to a variety of psychological issues [56, 57]. Among the countless affected variables, psychological resilience stands out as particularly impacted by Internet addiction, as observed in diverse research samples encompassing various ages, professions, and social statuses [58, 59]. In alignment with these findings, we anticipated the following outcomes:

Hypotheses 1 (H1): Psychological resilience scores of adolescents aged 12–14 are expected to decrease as their Internet addiction scores increase.

The intense experience of emotions specific to adolescence causes the emergence of many different emotional states, while at the same time, these emotions can be experienced at extremes [60]. Nowadays these emotions can be influenced by many different technological variables such as the Internet, social media, video games, et cetera [61–63]. These variables are also effective in the control and regulation of adolescents’ emotions [64, 65]. Furthermore, it is known that adolescents who regulate their emotions have high psychological resilience, which has a positive effect on emotion control [66]. In line with these:

Hypotheses 2 (H2): Anger control scores of adolescents aged 12–14 are expected to increase as their Internet addiction scores decrease.

Hypotheses 3 (H3): Anger control scores of adolescents aged 12–14 are expected to increase as their psychological resilience scores increase.

Last, since psychological resilience is theoretically and empirically linked to both Internet addiction and anger control [45, 58], and these two variables are related to each other [67]; we explored whether psychological resilience could mediate this relationship. In this context, we hypothesized:

Hypotheses 4 (H4): Psychological resilience mediates the effect of Internet addiction on the anger control of adolescents aged 12–14.

2. Methodology

The approval of the ethics committee and the permission of the rectorship for this research were obtained with the decision “126-5”. Permission was obtained from the Provincial Directorate of National Education on 07.10.2020 to apply the forms and scales. A relational model was used in this study, and the role of the mediating variable in the independent variable’s effect on the dependent variable was examined.

2.1. Participants and Procedure

The population of the study consists of students aged 12–14 attending secondary school in the Küçükçekmece district of Istanbul. As Kartal and Bardakci [68] stated, 0.5 p and q values for 0.5 sampling error in the sample size calculation table show 354 people. Considering the number of samples required for different population numbers, the sample number was determined as 384 secondary school students. The sample of the study consisted of 406 students aged 12–14 attending secondary school in the Küçükçekmece district of Istanbul. Among these students, 224 were girls and 182 were boys. Participants were selected using the convenience sampling method.

To justify the adequacy of our sample size, we consulted the guidelines provided by Fritz and MacKinnon [69] and Koopman et al. [70], both of which recommend a minimum sample size of 75–100 participants for mediation analyses. Additionally, we conducted a power analysis using the MedPower software [71], setting a target power of 0.80 to detect small path-related effects (i.e., 0.20). The power analysis indicated that a sample size of 250 participants would be sufficient to meet these criteria. Given that our sample consists of 406 participants, we consider it more than sufficient to ensure the validity and reliability of our analyses.

Table 1 shows the demographic features of the study. All participant read and accepted the study consent form.

| Variable | Groups | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade | 7th Grade | 205 | 50.5 |

| 8th Grade | 201 | 49.5 | |

| Gender | Girl | 224 | 55.17 |

| Boy | 182 | 44.83 | |

| Educational level of father | Primary school | 139 | 34.2 |

| High school | 123 | 30.3 | |

| University | 144 | 35.5 | |

| Number of siblings | None | 44 | 10.8 |

| 1 | 209 | 51.5 | |

| 2 | 106 | 26.1 | |

| 3 and more | 47 | 11.6 | |

| Educational level of mother | Primary school | 160 | 39.4 |

| High school | 138 | 34.0 | |

| University | 108 | 26.6 | |

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographic Information Form

This form was created by the researcher to gather information important for the research process. It includes questions about grade level, parents’ education levels, number of siblings, and other relevant factors.

2.2.2. The Internet Addiction Test (IAT)

The IAT was developed by Young [72] in 1998 to measure Internet addiction levels, the IAT, and it was adapted into Turkish by Bayraktar [73]. The scale consists of 20 items and is evaluated using a six-point Likert-type scale. Example items include: “Do you feel the need to use the Internet with increasing amounts of time in order to achieve satisfaction?” and “Have you repeatedly made unsuccessful efforts to control, cut back, or stop Internet use?” The Cronbach α internal consistency coefficient of the scale was calculated to be 0.91. Based on statistical evaluations, it is considered a valid and reliable tool for measuring Internet addiction levels in 12−14-year-old secondary school students.

2.2.3. Trait Anger and Anger Expression (T-Anger and AngerEX) Scales

The T-Anger and AngerEX scales, developed by Spielberger, Reheiser, and Sydeman [74] between 1980 and 1988, assesses individuals’ AngerEX styles and can be used with both adolescents and adults. It was adapted into Turkish by Özer [75] in 1994. This four-point Likert-type scale comprises 34 items, including the T-Anger scale with 10 items and the AngerEX scale with 24 items. The AngerEX scale is divided into three subscales: Anger-out, with eight items (e.g., “I express my anger”), Anger-in, with eight items (e.g., “I feel it inside, but I don’t show it”), and Anger-control, with eight items (e.g., “I control my temper”). Scores on the scale range from 24 to 96. In Özer’s [75] study, the internal consistency values (Cronbach’s α) were calculated as 0.77 for T-Anger, 0.80 for Anger-out, 0.73 for Anger-in, and 0.79 for Anger-control.

2.2.4. Child and Youth Resilience Measure (CYRM-12)

CYRM-12 was used to measure resilience in adolescents. The original 28-item form of the scale consists of three subscales and eight sub-dimensions [76]. However, the short-form study was carried out by Liebenberg, Ungar, and LeBlanc in 2013 [77] and a single 12-item structure was obtained as a result of two different studies. CYRM-12 includes items such as “I have people I look up to,” and “Getting an education is important to me.” This scale was adapted to Turkish by Arslan [78] in 2015. The Cronbach’s α value was calculated as 0.91. The factor loading values of the scale ranged from 0.39 to 0.88, and the internal consistency was found to be 0.84. The measurement tool, which has a five-point Likert structure, is rated between “A lot (5)” and “Not at all (1).” A high score indicates a high level of robustness. It is possible to say that the CYRM-12 is a valid and reliable scale that can be used to evaluate the resilience of children and adolescents in Turkey [78].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Percentage, frequency, mean, and standard deviation were used in the analysis of descriptive data. The assumption of normality regarding the variables of the study was evaluated with a box plot, stem and leaf plot, Q–Q plot, and data on skewness and kurtosis. As Tabachnick and Fidell [79] stated, a normal distribution is accepted when the kurtosis and skewness coefficients are between +1.5 and –1.5. In this study, it was decided to use parametric tests because the skewness and kurtosis values were between +1.5 and –1.5. In addition, the number of groups must be higher than 30 to use parametric tests [80]. Kruskal–Wallis H test was used for the differences between the groups. The PROCESS SPSS Macro was used to analyze the mediating effect. The analysis of the data was carried out with the Statistical Package Program for Social Sciences V22. In the current study, 5000 bootstrap samples were used during mediator variable analysis, as suggested by Hayes [81]. The fact that the lower and upper limit values of the confidence interval (LLCI and ULCI) do not include “0” indicates that the effect between variables is significant. In addition, the results of the Sobel test developed by Sobel over regression models were also included in testing the mediator effect [82].

3. Results

The study determined that there were statistically significant differences in scores on the IAT (H (4) = 130.696; p < 0.01), T-Anger (H (4) = 29.668; p < 0.01), Anger-control (H (4) = 21.845; p < 0.01), Anger-out (H (4) = 46.563; p < 0.01), Anger-in (H (4) = 25.518; p < 0.01) subscales, and resilience measure (H (4) = 35.069; p < 0.01) based on the duration of Internet use. For the Internet addiction scale, participants using the Internet for 2–5 h scored higher than those using it for less than 1 and 1–2 h, while those using it for 5–7 h scored higher than the less frequent users. Participants using the Internet for more than 7 h had the highest scores across all groups. In the T-Anger subscale, those using the Internet for 2–5 and 5–7 h scored higher than those using it for less than 1 h, and those using it for more than 7 h scored highest. For Anger-control, participants using the Internet for less than 1 h scored higher than those using it for longer durations, and those using it for 1–2 h scored higher than those using it for more than 7 h. In the Anger-out subscale, those using the Internet for 2–5 h scored higher than those using it for less than 1 and 1–2 h, while those using it for 5–7 h had higher scores than the 1–2 h users but lower scores than the less-than−1-h users. Participants using the Internet for more than 7 h scored higher than all other groups. In the Anger-in subscale, those using the Internet for more than 7 h scored higher than those using it for less than 1 h and 1–2 h. For the resilience measure, participants using the Internet for less than 1 h scored higher than those using it for 2–5, 5–7, and more than 7 h, while those using it for 1–2, 2–5, and 5–7 h scored higher than those using it for more than 7 h. Table 2 presents the Kruskal–Wallis H test results, which investigate the IAT, T-Anger and AngerEX scales, and CYRM-12 scores by Internet use duration.

| Scales | Groups | n | SO | H | df | p | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The internet addiction test (IAT) | Less than 1 h1 | 21 | 79.10 | 130.696 | 4 | p < 0.001 | 3 >1, 2 |

| Between 1–2 h2 | 86 | 120.26 | 4 >1, 2, 3 | ||||

| Between 2–5 h3 | 152 | 197.90 | 5 >1, 2, 3, 4 | ||||

| Between 5–7 h4 | 68 | 246.90 | — | ||||

| More than 7 h5 | 79 | 300.61 | — | ||||

| Trait anger (T-Anger) | Less than 1 h1 | 21 | 126.83 | 29.668 | 4 | p < 0.001 | 3, 4 > 1 |

| Between 1–2 h2 | 86 | 169.47 | 5 >1, 2, 4 | ||||

| Between 2–5 h3 | 152 | 209.73 | — | ||||

| Between 5–7 h4 | 68 | 201.16 | — | ||||

| More than 7 h5 | 79 | 250.95 | — | ||||

| Anger-control | Less than 1 h1 | 21 | 271.86 | 21.845 | 4 | p < 0.001 | 1 >3, 4, 5 |

| Between 1–2 h2 | 86 | 234.56 | 2 >5 | ||||

| Between 2–5 h3 | 152 | 198.61 | — | ||||

| Between 5–7 h4 | 68 | 197.97 | — | ||||

| More than 7 h5 | 79 | 165.69 | — | ||||

| Anger-out | Less than 1 h1 | 21 | 120.00 | 46.563 | 4 | p < 0.001 | 3 >1, 2 |

| Between 1–2 h2 | 86 | 150.52 | 4 >1, 2 | ||||

| Between 2–5 h3 | 152 | 213.29 | 5 >1, 2, 3 | ||||

| Between 5–7 h4 | 68 | 211.71 | — | ||||

| More than 7 h5 | 79 | 257.47 | — | ||||

| Anger-in | Less than 1 h1 | 21 | 144.31 | 23.518 | 4 | p < 0.001 | 5 >1, 2 |

| Between 1–2 h2 | 86 | 167.83 | — | ||||

| Between 2–5 h3 | 152 | 209.14 | — | ||||

| Between 5–7 h4 | 68 | 206.48 | — | ||||

| More than 7 h5 | 79 | 244.66 | — | ||||

| Resilience measure | Less than 1 h1 | 21 | 285.95 | 35.069 | 4 | p < 0.001 | 1 >3, 4, 5 |

| Between 1–2 h2 | 86 | 236.09 | 2, 3, 4 > 5 | ||||

| Between 2–5 h3 | 152 | 203.83 | — | ||||

| Between 5–7 h4 | 68 | 201.04 | — | ||||

| More than 7 h5 | 79 | 147.59 | — | ||||

In Table 3, the results of Pearson correlation analysis for investigating the relationship between resilience measure and T-Anger and AngerEX subscale scores are given. It was determined that there was a statistically significant relationship between resilience measure scores and T-Anger (r = −0.318; p < 0.01), Anger-control (r = 0.483; p < 0.01), Anger-out (r = −0.292; p < 0.01), Anger-in (r = −0.380; p < 0.01) subscales scores.

| Subscales | Resilience measure |

|---|---|

| T-Anger | −0.318 ∗∗ |

| Anger-control | 0.483 ∗∗ |

| Anger-out | −0.292 ∗∗ |

| Anger-in | −0.380 ∗∗ |

- ∗∗p < 0.01.

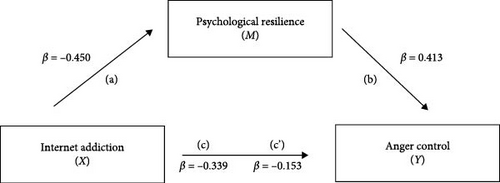

Table 4 shows the results of the regression analysis regarding the mediating role of resilience in the effect of Internet addiction on anger control. The model resulting from the regression analysis is given in Figure 1.

| Dependent variable | Independent variable | B | Standard errorB | β | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological resilience | Constant | 56.4079 | 0.672 | — | 83.8515 | p < 0.001 |

| Internet addiction | −0.214 | 0.021 | −0.450 | −10.1363 | p < 0.001 | |

| R = 0.450, R2 = 0.202, df:1/404, F:102.7449; p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Anger-control | Constant | 25.5366 | 0.480 | — | 53.2040 | p < 0.001 |

| Internet addiction | −0.109 | 0.015 | −0.339 | −7.2609 | p < 0.001 | |

| R = 0.339, R2 = 0.115, df:1/404, F:52.7206; p < 0.001 | ||||||

| Anger-control | Constant | 9.7437 | 1.896 | — | 5.1384 | p < 0.001 |

| Internet addiction | −0.049 | 0.015 | −0.153 | −3.1834 | p < 0.001 | |

| Psychological resilience | 0.280 | 0.032 | 0.413 | 8.5643 | p < 0.001 | |

| R = 0.501, R2 = 0.251, df:2/403, F:67.7548; p < 0.001 | ||||||

In the first stage of the regression analysis, the predictive effect of Internet addiction on resilience was examined. Internet addiction (β = −0.450, t = −10.136; p < 0.01) was found to explain 20.2% of psychological resilience. The established model was statistically significant (R = 0.450, R2 = 0.202, F (1, 404) = 102.745; p < 0.01).

In the second stage of the regression analysis, the predictive effect of Internet addiction on anger control was examined. Internet addiction (β = -0.339, t = −7.261; p < 0.01) explained 11.5% of anger control. This model was also statistically significant (R = 0.339, R2 = 0.115, F (1, 404) = 52.721; p < 0.01).

In the final stage of the regression analysis, the combined predictive effect of Internet addiction and resilience on anger control was examined. It was found that Internet addiction and psychological resilience (β = −0.153, t = −3.183; p < 0.01) together explained 25.1% of anger control. This model was statistically significant (R = 0.501, R2 = 0.251, F (2, 403) = 67.755; p < 0.01).

All necessary assumptions were met to test the mediating effect. Evaluating the β coefficients, the effect of Internet addiction (β = −0.339; β = −0.153) on anger control decreased when psychological resilience was included in the model as a mediator variable. The lower and upper limit values of the confidence interval were in the same direction (LLCI = −0.2375, ULCI = −0.1354). The Sobel test confirmed that resilience had a significant partial mediating role in the effect of Internet addiction on anger control (z = 9.20; p < 0.01).

4. Discussion

Since the beginning of human history, individuals have constantly adapted to meet their evolving needs through a variety of different resources [83]. These needs and the means of satisfying them have changed over time, reflecting social and technological advances. In the last decade of society, the Internet is an example of this dynamic, addressing a wide range of individual needs through a variety of platforms [84]. For example, numerous studies highlight the impact of online video games on psychological needs such as a sense of achievement, competition, and socializing [85, 86]. Likewise, studies show that social media platforms have a crucial impact on user satisfaction by facilitating connections, self-reflection, access to information, and more [87]. Thus, the Internet has transformed the way individuals satisfy their needs, highlighting the interplay between human needs and technological advances [88].

However, although most people use the Internet and many of its services in a healthy manner, a segment of the population may engage in dysfunctional use due to various real-life issues or underlying conditions [89]. This dysfunction can lead to many negative effects, sometimes resulting in pathological outcomes [49]. Therefore, understanding the factors that can prevent or reduce improper use of the Internet is crucial to promoting healthier use of the Internet and safeguarding individuals’ mental health. Moreover, given the high rates of Internet use among adolescents [90], as current statistics show, it is particularly important to address these issues within this population. Due to their developmental stage and increased vulnerability to external influences, adolescents are at increased risk of experiencing Internet-related dysfunctions and potential mental disorders [91].

In this context, this study aims to highlight the possible detrimental effects of Internet addiction on anger control and suggests that psychological resilience can provide a protective factor. By examining the relationship between Internet addiction and anger control, this study contributes to the understanding of how excessive Internet use can negatively affect emotional regulation. Furthermore, it is proposed that the support of psychological resilience could help to reduce these negative effects, thus, promoting healthier Internet use and better mental health outcomes. Unfortunately, studies on anger control and Internet addiction in adolescents are limited and there is a gap in the literature.

Overall, our study contributed to the literature by showing that there is a negative association between Internet addiction and psychological resilience in adolescents (H1). Thus, the predictive effect of Internet addiction on psychological resilience was analyzed in the first stage of the regression analysis. It was seen that Internet addiction explained 20.2% of psychological resilience, meaning that the established model was statistically negatively significant. Many studies in the literature have explored the relationship between psychological resilience and various forms of addiction [92, 93]. While Internet addiction is a relatively new diagnosis in this context, existing research suggests that psychological resilience negatively influences other addictions as well. In addition, studies focusing specifically on adolescents show that increasing psychological resilience can have a positive effect on their overall mood [94]. Moreover, the negative relationship found in this study may suggest a link between psychological resilience and coping strategies, implying that psychological resilience is associated with healthier coping mechanisms.

Our study revealed that there is a negative association between Internet addiction and anger control in adolescents (H2). The predictive effect of Internet addiction was studied in the second stage of the regression analysis and accounted for 11.5% of the anger control variance. The literature indicates a correlation between Internet use and increased aggressive behavior among adolescents. A study involving 8th-grade students found that 46.7% of participants encountered violent content during their online activities. Additionally, 37.3% expressed an interest in war-related content, including games, media, and visuals [95]. In the context of addiction, individuals often exhibit a low tolerance for life’s challenges and demonstrate difficulties in problem-solving. This may also reflect their inability to manage negative emotions, such as anger. Furthermore, it is plausible that individuals susceptible to Internet addiction lack the necessary skills to regulate their anger when engaging with online content.

Furthermore, our study showed that there is a positive association between psychological resilience and anger control in adolescents (H3). Indeed, high levels of psychological resilience were positively associated with anger control. Psychological resilience is strongly linked to the formation of healthy coping mechanisms, which play a crucial role in emotional regulation and the management of negative emotions [96]. Individuals with high levels of psychological resilience are better able to deal with challenges and stressors, using adaptive strategies to cope effectively [96]. This ability not only improves their overall emotional well-being, but also may promote greater control over negative emotions, such as anger.

Last, our research indicated that psychological resilience partially mediates the effect of Internet addiction on anger control in adolescents (H4). The common predictive effect of psychological resilience and Internet addiction on anger control was examined, and it was seen that psychological resilience and Internet addiction explained 25.1% of anger control. In line with the previous hypothesis, our findings suggest that while Internet addiction may reduce anger control, adolescents with higher levels of psychological resilience are better equipped to cope with this challenge. This finding can highlight the importance of healthy coping mechanisms, as resilient individuals can use adaptive strategies to effectively regulate their emotions. As a result, they improve their ability to manage anger, even in the face of Internet-related stressors.

According to the findings of the present study, it was revealed that psychological resilience has a significant partial mediating role in the effect of Internet addiction on anger control. These findings were supported by studies examining the relationships between Internet addiction and psychological resilience [59], Internet addiction and anger control [97], and psychological resilience and anger control [98]. The mediating role of psychological resilience in the effect of Internet addiction on anger control showed that a certain part of the negative effect of Internet addiction on anger control is the feelings of psychological resilience that are associated with Internet addiction.

Several limitations of this study need to be addressed. First, the study is still explorative and cross-sectional; consequently, no causality between the variables can be inferred. For instance, the robustness of the model tested could be investigated in the future distinguishing among the various types of Internet variables such as video games, social media, et cetera. Second, the study participants were exclusively Turkish, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, collecting data from a single country may further reduce its applicability to other contexts, as the sample reflects the Internet access opportunities and socioeconomic status specific to Turkey. Finally, dependence on self-report measures may be subject to bias, as individuals often tend to give socially acceptable rather than genuine answers. In addition, their capacity to evaluate their own behavior and feelings accurately may be limited, affecting the validity of the data collected [99]. Future research could also explore the role of other possible outcomes of having adolecents (e.g., anxiety, impaired self-efficacy, and guilt) in mediating or moderating the effect of psychological resilences on anger control. Also, nowadays, artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques are developing, future studies can analyze the variables of this study by using these techniques [100–102]. Moreover, given that other emotions in adolescents are as intense and distressing as anger, future studies should also focus on other emotional states.

5. Conclusion

This study demonstrated a negative association between Internet addiction and psychological resilience in adolescents, highlighting the detrimental effects of excessive Internet use on emotional regulation. Additionally, psychological resilience was found to partially mediate the impact of Internet addiction on anger control. These findings underscore the importance of fostering psychological resilience to mitigate the negative consequences of Internet addiction on adolescents’ mental health.

In light of the findings of this study, by promoting resilience, we can provide young people with effective coping strategies that address the immediate challenges of Internet use, while supporting long-term emotional well-being. This strategy not only helps to reduce aggressive behavior, but also improves overall mental health outcomes, supporting healthier developmental trajectories for young people in an increasingly virtual envoriment such as social media and video games. In addition, the findings of this study can inform the development of targeted intervention programmes to help adolescents better understand themselves. Such programmes may facilitate smoother navigation through the critical period of adolescence, ultimately enhancing their overall growth and well-being.

Ethics Statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The approval of the ethics committee and the permission of the rectorship for this research were obtained with the decision “126-5.” Permission was obtained from the Provincial Directorate of National Education on 07.10.2020 to apply the forms and scales.

Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: İnci Bakan Kıraç, Aida Sahmurova, and Mirko Duradoni. Methodology: Mustafa Can Gursesli and Mirko Duradoni. Investigation and data curation: İnci Bakan Kıraç and Aida Sahmurova. Writing–original draft preparation: Mustafa Can Gursesli, Andrea Guazzini, Aida Sahmurova, and Mirko Duradoni. Writing–review and editing: Andrea Guazzini, Mustafa Can Gursesli, İnci Bakan Kıraç, Aida Sahmurova, and Mirko Duradoni. Supervision: Aida Sahmurova and Mirko Duradoni. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.