Evaluation of Doctor–Patient Communication Regarding Medical Examinations Involving Ionizing Radiation: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

Background: Justification of medical exposures ensures that patient benefit outweighs the risks. The Western medicine philosophy and law emphasize the importance of informing patients about the risks of medical exposures as imperative for obtaining informed consent, especially in procedures involving ionizing radiation. This study investigated patient responses with regard to doctor–patient communication prior to diagnostic medical examinations that use ionizing radiation.

Methods: A cross-sectional design was used, where convenience sampling was utilized during recruitment of adult patients who had recently undergone diagnostic medical examinations involving the use of ionizing radiation. Included in this study were patients who had undergone such examinations within the past 12 months or were prescribed examinations involving the use of ionizing radiation.

Results: A total of 223 adult patients (aged 18 years and over [57% females and 43%]) participated in the study. The majority of patients (72.6%) were never informed by their physicians about the use of ionizing radiation in their prescribed medical examinations. However, 27.4% patients were informed about the possible risks resulting from their prescribed examinations.

Conclusion: A noticeable deficiency in doctor–patient communication regarding the risks associated with medical ionizing radiation was established. Furthermore, patient involvement in the decision-making process concerning the choice of examination was found to be limited.

Implications for Practice: Improved communication strategies can benefit both patients and clinicians. This can be achieved through provision of easily accessible reading materials on medical tests, explaining their advantages and disadvantages, thus empowering both patients and clinicians fostering shared decision-making.

1. Introduction

Computed tomography (CT), single-photon computed tomography (SPECT), positron emission tomography (PET), and conventional x-ray modalities play a significant role in patient management. These modalities use ionizing radiation to visualize the human body and organs inside the body [1]. Despite patient benefits, there are concerns over patient exposure from ionizing radiation [2]. The World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer classifies ionizing radiation, encompassing x-rays and gamma rays as carcinogenic. The potential detrimental health effects of ionizing radiation can manifest as either stochastic or deterministic effects [3]. The stochastic effects are more concerning due to their probabilistic nature. Unlike deterministic effects, they do not have a defined minimum threshold for occurrence [4]. They contribute to radiation-induced mutations and increased long-term risk of cancer induction. However, the benefits of radiation derived from medical exposures outweigh the potential risks [4, 5]. Despite patients being the primary subjects of medical imaging, it has been established that they exhibit limited awareness of the risks associated with radiation exposure during medical imaging [5].

The Ionizing Radiation (Medical Exposure) Regulations of 2017 (IR [ME] R2017) enshrines the right of patients to be informed about the benefits and risks of medical ionizing radiation [6]. As such, effective risk communication is paramount in ensuring informed consent from patients undergoing medical imaging examinations [7]. Patients should not only be informed of the benefits and risks of medical examinations but should also be presented with alternative imaging methods [7, 8]. Knowing and understanding the risks of medical ionizing radiation empower patients in making informed decisions about their healthcare, including attending or abstaining from planned or prescribed examinations. However, the effectiveness of risk communication hinges on the information given, how it is delivered, and the patient’s level of understanding [9, 10].

This study addresses the critical gap in understanding patient perspectives on doctor–patient communication preceding medical examinations involving the use of ionizing radiation. It seeks to evaluate the current state of communication practices and shed light on areas that may require improvement to ensure patients are well-informed, actively involved, and empowered in their healthcare decision-making process.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Data Collection

This study used a cross-sectional survey. Adult patients (aged 18 years and over) awaiting medical examinations at the tertiary hospital were surveyed. Three trained MSc students acting as interviewers administered the questionnaire to eliminate misunderstandings and to ensure adherence to ethical standards.

Convenience sampling was employed to select adult patients who had undergone diagnostic medical examinations involving x-rays, CT, SPECT/CT, or PET/CT at least once in the past 12 months including those scheduled for upcoming examinations. Only patients who gave consent were enrolled in this study. Patients who were too ill or suffered from severe injuries and those who did not give consent were excluded from the study.

2.2. Questionnaire Development

A questionnaire consisting of 12 items organized into two sections was developed for this survey (Appendix 1 in the Supporting Information). The first section aimed to extract demographic information (gender, age, and educational level). The second section explored communication gaps between doctors and patients prior to prescribing medical examinations involving medical radiation. The semantic structure and appropriateness of each item in the questionnaire were evaluated by three senior members of the department of medical physicists who provided an expert opinion. After modification and optimization, 12 items remained in the questionnaire. These were finally validated by the coresearcher with several years of experience in radiation protection. Once validated, the questionnaire was pretested among 12 patients for content validity. However, these patients were not included in the final survey.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The raw survey data collected in this study were systemically coded to facilitate computer-readable processing. Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM’s Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26. Descriptive statistical methods including frequency distributions were employed to summarize data. Comparative analytic statistical methods were performed to explore the relationships between doctor–patient communication practices and demographic variables such as gender, age, and educational background. Fisher’s exact test was used for analyses of small expected cell counts, and the chi-square test was applied otherwise. The threshold for statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05 (two-tailed). Prior to analysis, assumptions for each test were verified.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University Research Ethics Committee (reference number SMUREC/M/56/2022:PG). In order to maintain participant privacy and confidentiality, the participants were requested not to write their names on the questionnaire and any information that may lead to their identification. Furthermore, the name of the hospital was excluded in this article, and it remains known only to the researchers. Prior to the commencement of the study, consent was obtained from all participants. Only participants who gave consent were enrolled in the study.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics and Selection

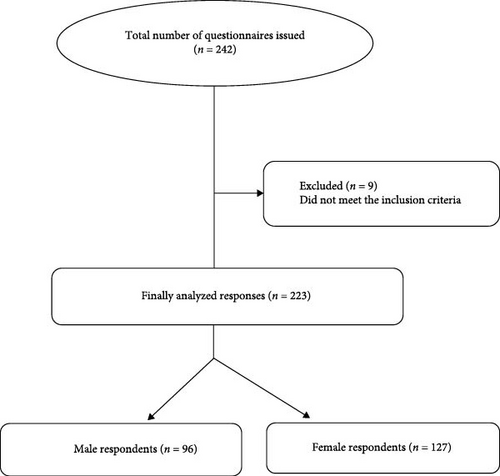

A total of 242 hard-copy questionnaires were distributed, and the response rate was high 223/242 (92%). The participating cohort comprised of 127 females (57%) and 96 males (43%) (Figure 1).

Among the 223 patients, their educational levels varied. Thirty-one out of 223 patients (13.9%) had low education (primary schooling), and 10/223 patients (4.5%) had no formal education. In contrast, 107/223 patients (48.0%) completed secondary school, 60/223 patients (26.9%) had diploma qualifications, and 15/223 patients (6.7%) possessed degree qualifications. The mean age of patients was 37.2 years, with 5.8% of patients over 65 years old and 23.3% falling within the middle age category (Table 1).

| Age distribution | Number of patients | Percentage (%) of patients |

|---|---|---|

| 18–25 | 28 | 12.6 |

| 26–35 | 47 | 21.1 |

| 36–45 | 50 | 22.4 |

| 46–55 | 52 | 23.3 |

| 56–65 | 33 | 14.8 |

| Over 65 | 13 | 5.8 |

| Total | 223 | 100.0 |

3.2. Patients’ Perspectives on Sharing Information About the Prescribed Examinations

For the majority of participants, 194/223 (87%) expressed comfort in sharing information about their medical examinations with researchers, while 13/223 (5.8%) reported feeling unsettled about sharing such information. However, a smaller proportion, 16/223 (7.2%), remained undefined in their views.

3.3. Types of Medical Examinations Undergone

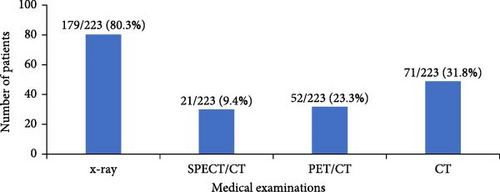

Figure 2 shows the distribution of medical examinations involving the use of ionizing radiation that the 223 participants underwent over the past 12 months or those scheduled during the study. Among the respondents, 179/223 (80.3%) reported conventional x-rays, 21/223 (9.4%) SPECT/CT, 52/223 (23.3%) PET/CT, and 71/223 (31.8%) CT scans.

3.4. Number of Imaging Test Prescribed

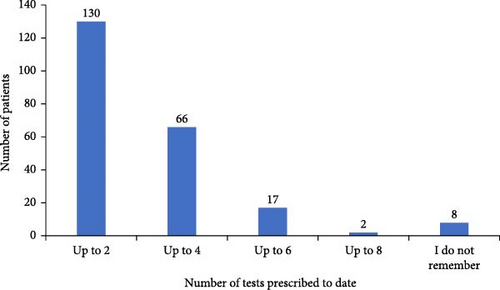

A majority of patients 130/223 (58.3%) reported having undergone one to two scans prior to this study (Figure 3).

3.5. Doctor–Patient Communication

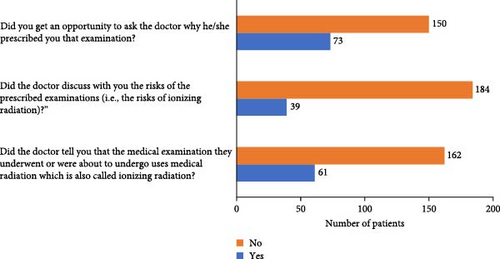

Patients were asked about the origin of the medical examination request. Among the surveyed patients, 211/223 (94.6%) had the medical examination prescribed by the doctor, while 12/223 (5.4%) requested the doctor to prescribe for them the examination. A total of 150/223 (67.3%) did not get an opportunity to ask the doctor why a particular examination was prescribed for them, while 73/223 (32.7%) did have such an opportunity. One hundred eighty-four out of 223 (82.5%) patients were prescribed medical radiation examinations without any discussion about the associated risks, whereas only 39 (27.4%) were informed about the risks of being exposed to ionizing radiation during imaging.

Lastly, 162/223 (72.6%) patients were never told by doctors that the prescribed medical examinations used ionizing radiation, while 61/223 (27.4%) were informed by their referring doctors (Figure 4).

Table 2 represents the responses of patients per age group to questions that sought to establish if there existed doctor–patient communication with regard to the nature of examination prescribed that involved the use of ionizing radiation.

| Question | Percentage responses | Yes (%) | No (%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did the doctor tell you that the medical examination they underwent or were about to undergo uses medical radiation which is also called ionizing radiation? | Gender | Male | 24 (25%) | 72 (75%) | 0.493 |

| Female | 37 (29.1%) | 90 (70.9%) | |||

| Age group | 18–25 | 6 (21.4%) | 22 (78.6%) | <0.001 | |

| 26–35 | 22 (46.8%) | 25 (53.2%) | |||

| 36–45 | 19 (38%) | 31 (62%) | |||

| 46–55 | 11 (21.2%) | 41 (78.8%) | |||

| 56–65 | 2 (6.1%) | 31 (93.9%) | |||

| Over 65 | 1 (7.7%) | 12 (92.3%) | |||

| Educational level | No formal education | 0 (0.0%) | 10 (100%) | <0.001 | |

| Primary school | 1 (3.2%) | 30 (96.8%) | |||

| Secondary school | 28 (26.2%) | 79 (73.8%) | |||

| Diploma | 26 (43.3%) | 34 (56.7%) | |||

| Degree | 6 (40%) | 9 (60%) | |||

| Did the doctor discuss with you the risks of the prescribed examination (i.e., the risks of ionizing radiation)? | Gender | Male | 15 (15.6%) | 81 (84.6%) | 0.592 |

| Female | 24 (18.9%) | 103 (81.1%) | |||

| Age group | 18–25 | 4 (14.3%) | 24 (85.7%) | 0.087 | |

| 26–35 | 11 (23.4%) | 36 (76.6%) | |||

| 36–45 | 14 (28.0%) | 36 (72.0%) | |||

| 46–55 | 7 (13.5%) | 45 (86.3%) | |||

| 56–65 | 2 (6.1%) | 31 (93.9%) | |||

| Over 65 | 1 (7.7%) | 13 (92.3%) | |||

| Educational level | No formal education | 0 (0.0%) | 10 (100.0%) | <0.001 | |

| Primary school | 1 (14.0%) | 30 (86.0%) | |||

| Secondary school | 15 (14.0%) | 92 (86.0%) | |||

| Diploma | 18 (30.0%) | 42 (70.0%) | |||

| Degree | 5 (33.3%) | 10 (66.7%) | |||

| Did you get an opportunity to ask the doctor why he/she prescribed you that examination? | Gender | Male | 29 (30.9%) | 65 (69.1%) | <0.001 |

| Female | 44 (36.7%) | 76 (63.3%) | |||

| Age group | 18–25 | 12 (42.9%) | 16 (57.1%) | 0.024 | |

| 26–35 | 18 (38.3%) | 29 (61.7%) | |||

| 36–45 | 18 (37.6%) | 30 (62.5%) | |||

| 46–55 | 21 (40.4%) | 31 (59.6%) | |||

| 56–65 | 6 (18.2%) | 27 (81.8%) | |||

| Over 65 | 0 (0.0%) | 13 (100.0%) | |||

| Educational level | No formal education | — | — | 0.002 | |

| Primary school | 3 (9.7%) | 28 (90.3%) | |||

| Secondary school | 40 (37.4%) | 67 (62.6%) | |||

| Diploma | 25 (43.1%) | 33 (56.9%) | |||

| Degree | 7 (46.7%) | 8 (53.3%) | |||

From Table 2, it can be observed that more patients between the age of 26 and 35 years indicated that the doctor informed them that the medical examination they underwent uses ionizing radiation; a statistically significant association was established between the participants’ response and age when responding to the question “Did the doctor tell you that the medical examination you underwent uses medical radiation which is also called ionizing radiation?” (26–36 years old, 22/47 [46.8%] vs. over 65 years old, 1/13 [7.7%] p-value < 0.001).

Most female patients indicated that they were informed about the risks of ionizing radiation. However, no significant association was determined between the participants’ response and gender when responding to the question “Did the doctor discuss with you the risks of the prescribed examination (i.e., ionizing radiation)?” (female 24/127 [18.9%] vs. male 15/96 [15.6], p-value < 0.592). Less than 50% of patients with degrees showed that they had an opportunity to ask doctors questions about the prescribed medication; a statistically significant association was found between the participants response and the level of education when responding to the question “Did you get an opportunity to ask the doctor why he prescribed you the particular examination?” (degree 7/15 [46.7%] vs. primary school 3/31 [9.6%], p-value = 0.002).

4. Discussion

The study highlights a common concern of limited shared decision-making between the doctor and patient with regard to the choice of the imaging examinations that involves the use of ionizing radiation. This limitation is not unique to this sample of patients (n = 223) who were exposed to ionizing radiation while undergoing medical imaging examinations. Lumbreras et al. [9], in a similar study, highlighted limited information received by the general population from the health professionals with regard to the radiation exposure associated with five different diagnostic imaging tests. Similarly, in another study by Bastiani et al. [11], more than half of the surveyed patients (n = 2866) were unaware of the risks associated with exposure during medical examinations due to not receiving any such information prior or after the medical examinations. This was despite existent mandatory legislation in Italy that compels prescribers of medical radiation tests to inform patients about the risks associated with the test and also to keep a record and report on patient doses [11].

The findings from our study including those from the studies by Lumbreras et al. [9] and Bastiani et al. [11] are contrary to the fact that “medicine is an art whose magic and creative ability that has long been recognized as residing in the interpersonal aspects of patient–physician relationship" [12]. Furthermore, effective doctor–patient communication is the cornerstone in delivery of high-quality healthcare services [13]. However, this was established to be a limitation not only in this study but also in the study by Bastiani et al. [11], in which they established that among the respondents who were knowledgeable about radiation dose or risk associated with radiological examinations, they had acquired it outside the healthcare system either through radio or television programs.

In this study, 61/223 (27.4%) were informed by their referring doctors about the risks associated with medical examinations. This number was very small compared to 1224/2866 (42.7%) of respondents in a survey conducted in Italian hospitals by Bastiani et al. [11]. Although our sample was small (n = 223) compared to n = 2866 from 16 teaching and nonteaching Italian hospitals [11], it was representative enough for this comparison as the sample was from a referral hospital that service patients from more than three provincial hospitals.

A total of 162/223 (72.6%) patients were never told by doctors that the prescribed medical examinations used ionizing radiation. Similarly, in a study by Bastiani et al. [11], 1273/2866 (44.4%) of respondents were never informed about their doctors about the risks associated with medical radiation.

A total of 150 patients (67.3%) did not get an opportunity to ask the doctor why they prescribed the particular examination. However, this figure was lower than that of an Australian study where it was reported that 85.6% of patients did not have any discussion with the doctor on radiation exposure or associated risk when referred to a diagnostic imaging procedure as well as previous procedures [14].

Failure to engage patients may have been attributed to poor knowledge and practice [15]. For instance, a Korean study undertaken from 2011 to 2016 established that 61% of pain physicians did not receive any radiation safety education [16]. Furthermore, a systematic review conducted recently by Ribeiro et al. [17] established a limitation on knowledge among healthcare professionals (physicians, radiographers, and nuclear medicine technologists) on ionizing radiation exposure as the main contributing factor. A systematic review of 14 peer reviewed articles established that physicians underestimated the degree of ionizing radiations exposure. They could not distinguish imaging procedures that use ionizing radiation from those that do not use ionizing radiation [17, 18].

In this current study, it was also established that 73/223 (32.7%) had an opportunity to ask doctor questions on why they were being prescribed that particular imaging examination. This figure was much higher than that of a Finish study with a smaller sample (n = 147) patients which included 13 PET/CT and 11 bone scans patients [8]. Discussing with patients is in line with the European Directive 2013/59/Euratom that detects that clinicians should consider medical doses when prescribing medical examination and also inform the patients about such exposures [19]. However, in South Africa, there is no regulation that compel doctors to inform patients about the medical exposures and later alone to discuss about the risks of medical exposures. This probably explains why doctors did not discuss the risks of the prescribed medical radiation exposures or prescribed imaging tests with 184/223 patients (82.5%). However, this situation was also prevalent in Italian hospitals despite the existence of a mandatory regulation that demands patients to be informed about radiation doses [11].

According to Ribeiro et al. [17], several factors influence discussions between doctors and patients. These include differences in education and training in different countries. Also, of significance is the information sent to the patient about the risks of medical ionizing radiation prior to the medical examination in the form of leaflets. In this study, patients did not receive any information about the risks and benefits of the medical examination prior to attending their examinations. However, we could not measure the level of knowledge of clinicians in this study. As such we are unable to conclusively link failure to discuss the risks and benefits of imaging examinations involving radiation to the clinician’s knowledge and awareness on the risks and benefits except to possibly make a link with procedural issues. This procedural issue was also raised by Ribeiro et al. [17], who questioned on who should be involved with patients in discussion of the risks and benefits of radiation exposure and when to do so. In the European Union (EU), all member states are obliged to inform patients about the risks and benefits of medical procedures involving the use ionizing radiation. Radiographers are delegated with the responsibility of information the patients [20].

Similarly, in Norway, the legislation mandates that patients be provided information on risks, potential harm, and doses associated with medical imaging [21]. However, concerns have been raised about radiographers who do not adequately communicate relevant information to patients [8].

The educational level of the patients may have also limited their desire to ask or discuss with doctors the risks and benefits of medical radiation. For instance, only 15 patients (6.7%) had a degree qualification, while 60 patients (26.9%) had a diploma qualification. The rest had lower educational qualifications (31 patients [13.9%] [primary schooling], 10 patients [4.5%] did not have formal education, and 107 patients [48.0%] had a secondary school education).

Despite patient participation being the recognized key component in the envisaged redesign of the healthcare process [8], the fact that the majority of patients were either secondary education or lower educational level may have made it difficult to partake in choosing the imaging modality. Furthermore, terms used in radiation safety are sometimes complex and regarded as jargon. Even if the doctor would have discussed with patients the risks and benefits, it may not have been helpful considering their academic level in the case of this study. We can only assume that those who managed to discuss with the doctors the risks and benefits of radiation were those with diploma and degree qualifications.

According to Longtin et al. [22], a patient exercises his/her fundamental right by participating in decision-making process concerning their health matters. Furthermore, patient participation is influenced by educational background. The study also established that the doctors only communicated to 61 patients (27.4%) that the medical examination used ionizing radiation. However, this number was slightly higher than that reported by a Canadian study which has showed that only 8% of patients were informed by their prescribers of the risks of exposure to ionizing radiation during radiological examinations [23].

An analysis of the number of scans undergone by individual patients interviewed showed that the majority of patients 130/223 (58.3%) had one or two tests within 12 months. However, for minority, 19/223 (8.5%) said that they received six scans within 12 months. Failure by doctors to discuss the risk of exposure may have contributed to patients unknowingly agreeing to undergo as many as six imaging tests (scans), despite the fact that even low dose from medical imaging may result in stochastic effects [24]. The stochastics effects are known to result from mutation or permanent damage to the cell. These include hereditary effects and cancer, and their severity increases with dosage [25], hence the concern over a patient undergoing as many as six imaging tests using a modality that uses ionizing radiation. Lam et al. [26] argue that the radiology community has the professional responsibility of communicating the risks of medical ionizing radiation to patients.

In an open-ended question, patients were asked if they were satisfied about the answer given to them by the doctor, and those who did not have an opportunity were asked to give brief statement why they did not ask doctors questions regarding the examination prescribed to them.

Among the 73 patients given the opportunity to ask questions to the doctor, 23 of them answered a follow-up question regarding satisfaction with the answers provided by the doctor. Of these 23 patients, 5/23 (27.8%) were satisfied, while 9/23 (39.1%) expressed dissatisfaction due to language barriers.

Among the 150 patients who did not have an opportunity to ask why the examination was prescribed to them, only 77/150 (51.3%) commented on satisfaction. Of these, 31/150 (22%) patients expressed that they were too scared to ask any questions, while 9/150 (6%) indicated that they were only concerned with getting help without any delays; hence, they did not ask any questions.

5. Conclusion

A substantial communication deficit was found to exist between patients and doctors regarding the risks of medical ionizing radiation. Furthermore, it was established from this study that the majority of patients were not involved with the selection of their medical examination. The communication deficit can be overcome by enhancing patient awareness and involvement in their healthcare. Patient involvement can guarantee ethical and patient-centered care in imaging tests that involve the use of ionizing radiation.

6. Limitations of the Study

While this study findings provide valuable insights into doctor–patient communication regarding prescription of medical examinations involving ionizing radiation, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the study did not capture the clinical indications that necessitated repeated imaging. This limitation hindered the ability to assess whether the benefits of the repeated examination outweighed the associated risks, particularly regarding patient safety. Second, the absence of clinical indication data made it challenging to evaluate whether nonionizing imaging modality could have been a viable alternative to the prescribed ionizing imaging modality. Addressing these limitations in future research could improve understanding and support more informed decision-making in clinical practice.

Ethics Statement

The study was approved by the Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University Research Ethics Committee (reference number SMUREC/M/56/2022:PG).

Consent

Only participants who gave consent through signing the consent form participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

There was no funding for this project.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the clinical director for Dr. George Mukhari Academic Hospital for granting permission for the study to be conducted in the hospital.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The participants’ information is readily available from the authors.