The Quality of Life of Pseudomyxoma Peritonei Patients: A Scoping Review

Abstract

Background. Pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) is a form of peritoneal malignancy. It originates from a perforated appendiceal epithelial tumour. Patients with PMP experience various stressful and traumatic events including diagnosis with a rare disease, treatment with extensive and complex surgery, and long hospital stays. Currently, there is a scarcity of studies that primarily aim to assess the quality of life of patients with PMP, and there is no reviews or comprehensive understanding of the quality of life (QoL) issues faced by these patients. Even fewer studies have consulted with patients themselves. Objective. To review the current literature on the QoL of patients with PMP and answer two main questions: What methods are being used to assess the QoL patients with PMP and what are the main findings?. Methods. For the scoping review, five scientific databases were searched (CINAHL, EMBASE, Pubmed, PsycInfo, and Medline). Publications that were published between 2002 and 2022 and in English were included in this review. Studies were screened by two independent reviewers against the review’s eligibility criteria. Data related to the QoL of patients with PMP in the included studies were extracted to answer two main questions (what were the methods used to assess QoL in this population, and what were the findings?). The extracted data was presented in table form and qualitatively analyzed using content analysis. Findings. Fourteen studies were included in this review. Only five studies out of fourteen assessed the QoL of patients with PMP as a main outcome, and all these studies assessed QoL in relation to surgery. Studies that assessed QoL used different validated measures. There was a consensus among studies that patients’ QoL improved by 12 months posttreatment. The most commonly cited symptom of PMP in this review is abdominal pain. Conclusion. The evidence on the QoL of patients with PMP is limited. Studies that assess the quality of life of these patients independent of surgery are needed. There is no consensus on the measure used to assess QoL in this population.

1. Introduction

Pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) is a form of peritoneal malignancy [1]. It originates from a perforated appendiceal epithelial tumour and affects 22 individuals per million worldwide [1, 2]. The cancer spreads along the peritoneum, a thin layer that protects the abdominal organs, and can involve the surface of all abdominal organs [3]. Without treatment, PMP is a fatal condition [4]. The unlimited multiplication of peritoneum cells can fill the space needed in the abdomen for normal gastrointestinal functioning, leading to compression of bowel organs, disruption of their functioning, and starvation [5].

The most common treatment for PMP is cytoreductive surgery (CRS) followed by hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) [5]. CRS entails removing the peritoneum and other affected tissues [5]. CRS is an extensive and complex surgery [4]. HIPEC is a therapy that uses chemotherapy that is applied directly to the abdomen [5]. Patients with PMP experience various stressful and traumatic events, including diagnosis with a rare disease, treatment with extensive and complex surgery, admission to intensive care for an average of 5 days, and then on a surgical ward for an average of 3 weeks [6].

There are a few studies that primarily aim to assess the quality of life of patients with PMP [7–10] but there is no systematic or comprehensive review of the literature. A review is needed for a better understanding of the findings around the quality of life of patients with PMP. Collating and reviewing the current findings will help inform clinicians and patients and will guide future research by highlighting current knowledge gaps.

2. Materials and Methods

The authors’ initial aim was to conduct a systematic review of the literature on the quality of life of patients with PMP. However, after the initial search, it was decided that a scoping review would be more appropriate, as the current literature on the quality of life of patients with PMP is too limited. Scoping reviews are used to answer specific questions, summarize the characteristics of the studies that have been published in the field, and identify knowledge gaps [11]. Thus, a scoping review would allow the authors to answer their questions about the quality of life of patients with PMP from the limited research available. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) was used to structure this review [12].

2.1. Objectives

- (1)

What are the main methods/questionnaires used to assess the quality of life (QoL) of the patients with PMP?

- (2)

What are the current main findings around the QoL of patients with PMP?

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

Publications that were published between 2002 and 2022 and in English were included in this scoping review. Studies were screened to ensure that they assessed the symptoms, experiences, complaints, issues, and/or the quality of life of patients with PMP.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

Conference abstracts and dissertation abstracts were excluded. This was done to ensure that the results presented in this scoping review represented the peer-reviewed evidence on the experiences of patients with PMP in order to identify the gap in this literature. Studies that had a heterogeneous population (different cancer types) were assessed further to identify if the symptoms, experiences, complaints, or quality of life domains of patients with PMP could be extracted separately; if not, then such studies were excluded.

2.3. Information Sources

On 11th of February 2022, five scientific databases were searched: CINAHL, EMBASE, Pubmed, PsyInfo, and Medline. There were no limits on date or language (publications that did not meet the language or date inclusion criteria were excluded during the screening process). The search strategy is presented in Appendix A.

2.4. Selection of Sources of Evidence

One author (RT) conducted the search, exported the results into an Excel spreadsheet, and removed all duplicates. To increase consistency among authors, three authors (RT, JR, and DG) independently screened the retrieved titles and abstracts against the inclusion and exclusion criteria and denoted their decision (include/exclude) per study. The full texts of all papers that were included by at least one author were retrieved. Two authors (RT and DG) then independently screened the full texts against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. All disagreements on study selection were resolved through a discussion between the authors.

2.5. Data Charting Process

All included papers were imported into NVivo [13]. RT analyzed the data using qualitative content analysis to extract any data relating to the symptoms, complaints, issues, or quality of life of patients with PMP. The characteristics of each paper—methods (including quality of life measures used) and symptoms or quality of life-related findings—were also extracted.

2.6. Data Items

- (i)

Study title, author, country, year of publication, publication type, aim, methods, sample size and characteristics, and quality of life-related results.

- (ii)

Quality of life questionnaire(s) used.

- (iii)

Symptoms/complaints/issues/quality of life-related findings (before/after treatment).

2.7. Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

The characteristics of the studies included in this review are presented in table form. A list of the questionnaires used to measure the quality of life was produced. A table was generated to list the symptoms/complaints/issues that affect the quality of life of patients with PMP pre- and posttreatment. The items in the list were ranked based on the frequency of mentions in publications.

3. Results

3.1. Selection of Sources of Evidence

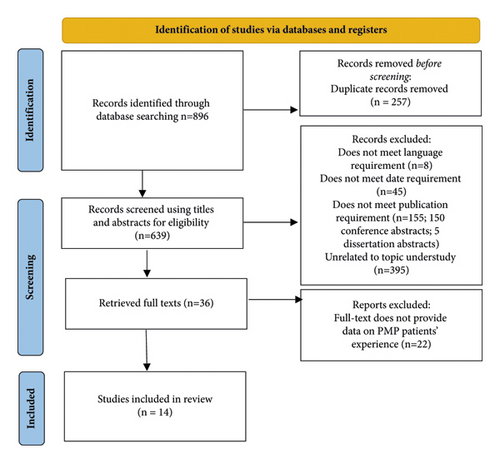

The initial search resulted in 896 results of which 14 studies were included in this review. See Figure 1 for the PRISMA flowchart [14].

3.2. Characteristics of Sources of Evidence

The included studies in this review were published between 2004 and 2018. Studies were geographically well spread (UK, Japan, France, Australia, India, Finland, Denmark, Hong Kong, and Saudi Arabia). They included one review [15], two case studies [16, 17], one qualitative study [5], and ten quantitative studies [7–10, 18–23]. See Table 1 for further details on the studies’ characteristics.

| Title | Authors | Country | Year | Paper type | Main aims | Method used to assess QoL | Sample size and characteristics | QOL related results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of life after intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal carcinomatosis [23] | McQuellon et al. | Saudi Arabia | 2004 | Research Article | Investigate the impact of infusing intraperitoneal chemotherapy (IPCT) using Cisplatin 50–100 mg/postpalliative abdominal paracentesis to delay fluid accumulation to the abdominal cavity on patients’ symptoms and quality of life | Functional Assessment of cancer treatment General (FACT-G) | N = 12 (of which only 1 had PMP). No demographic data were provided | Both quality of life and symptoms improved after intraperitoneal chemotherapy (IPCT) in the PMP patient |

| Pseudomyxoma peritonei: Role of cytoreduction and intraperitoneal chemotherapy [17] | Choi et al. | Hong Kong | 2004 | Case study | Present a case study | NA | N = 1; 61-year-old woman | None |

| A study to explore the patient’s experience of peritoneal surface malignancies: pseudomyxoma peritonei [5] | Withama et al. | UK | 2008 | Research Article (qualitative) | Explore the effect of PMP on patients’ lives | A qualitative study design using semistructured individual interviews | N = 13. Six (46%) patients were male and seven (54%) were female. Four (31%) were aged below 50, five (38%) were aged between 50 and 59, and four (31%) were aged over 60 | Themes: uncertainty, difficulties confirming diagnosis, and living with an uncertain prognosis |

| Quality of life after cytoreductive surgery plus early intraperitoneal postoperative chemotherapy for pseudomyxoma peritonei: a prospective study [9] | Jess et al. | Denmark | 2008 | Research Article | Investigate the impact of cytoreductive surgery plus early intraperitoneal postoperative chemotherapy on quality of life | Short Form-36 questionnaire, EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-CR38 | N = 23. The median age was 53.8 men and 15 women | CRIS and EPIC had little impact on quality of life and only shortly after surgery. Scores returned to baseline after 6 months postsurgery |

| Clinical presentation of pseudomyxoma peritonei [18] | Järvinen and Lepistö | Finland | 2010 | Research Article | To characterize the manifestations of PMP | Analyzed the hospital records of patients with PMP | N = 82 of which 53 were women and 29 were men. Mean age at the time of diagnosis was 52.3 | Abdominal pain was the most common complaint (23%) |

| Prospective longitudinal study of quality of life following cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy for pseudomyxoma peritonei [8] | Alves et al. | UK | 2010 | Research Article | Asses the quality of life of PMP patients at baseline (preoperatively) and postoperatively and compare the quality of life of patients who had a complete surgery (removal of all macroscopic disease) and a major debulk surgery | European Organization for research and treatment of cancer (EORTC) QLQ-C30 questionnaire | N = 49.13 males and 36 females. Median age of 55 | QoL improved 1 year after surgery in both the complete cytoreduction and major tumour debulking |

| Palliative effects of an incomplete cytoreduction combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy [22] | Chua et al. | Australia | 2010 | Research Article | Investigate whether the outcome of an incomplete cytoreduction followed by administering perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy prolongs survival or palliates symptoms | A retrospective review of a prospectively collected database of patients’ clinical notes was performed | N = 11.7 males and 4 females. Median age was 54 (only 7 patients had PMP) | Symptomatic benefits occurred in people with incomplete surgery (some disease left). Symptoms improved in 5 PMP patients |

| Cytoreductive surgery with intraperitoneal chemotherapy to treat pseudomyxoma peritonei at nonspecialized hospitals [21] | Kitai et al. | Japan | 2011 | Research Article | This study aims to investigate the benefits and risks of the Sugarbaker procedure | Review the clinical patients with PMP. | N = 15. Four (26.7%) patients were male and eleven (73.3%) were females, with an average age of 60.5 years | After a median follow-up period of 43 months, all of the 12 patients with complete cytoreduction were alive and disease-free with good quality of life |

| Pseudomyxoma peritonea: Uncommon presentation [16] | Gandhi and Nagral | India | 2012 | Case study | Present a case study | NA | N = 1; 60-year old man | None |

| Quality of life study following cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy for pseudomyxoma peritonei including redo procedures [7] | Kirby et al. | Australia | 2013 | Research Article | Evaluate the quality of life of pseudomyxoma peritonei following cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy | FACT C (version 4) quality of life questionnaire, and FACIT-TS-G (version 1) questionnaires | N = 63, thirty-nine (62%) of the participants were females. Average age of 54 years | There was no significant difference in the quality of life scores between patients who had a single versus redo procedure |

| Secreted mucins in pseudomyxoma peritonei: pathophysiological significance and potential therapeutic prospects [15] | Amini et al. ∗ | Australia | 2014 | Review | Present a review of PMP its diagnosis, treatment and prognosis | NA | 0 | Not applicable |

| Can a benefit be expected from surgical debulking of unresectable pseudomyxoma peritonei? [20] | Delhorme et al. | France | 2016 | Research Article | Evaluate the role of surgical debulking in improving the symptoms of PMP is patients | Retrospective analysis of a database of all patients in a tertiary care center treated for PMP | N = 338.21 (54%) males and 18 (46%) females. The median age was 59 | Major tumor debulking can relieve PMP-related symptoms over a median time of almost 2 years |

| Should total gastrectomy and total colectomy be considered for selected patients with severe tumor burden of pseudomyxoma peritonei in cytoreductive surgery? [19] | Liu et al. | Japan | 2016 | Research Article | Assess survival morbidity and mortality after CRS as well as perioperatively | EORTC QOL-C30 questionnaire | N = 48. Twenty-eight (58.3%) patients were male and twenty (42%) were female. The median age was 52.5 years | Patients receiving CRS including total gastrectomy and total colectomy could have a similar quality of life as other patients after 6 months postsurgery |

| Long-term quality of life after cytoreductive surgery and heated intraperitoneal chemotherapy for pseudomyxoma peritonei: A prospective longitudinal study. [10] | Stearns et al. | UK | 2018 | Research Article | Evaluate long-term health related quality of life (HRQL) for patients with PMP | (EORTC)-QLQ C30 HRQL questionnaire |

|

12 months postsurgery, CRS-HIPEC for PMP is associated with a good quality of life except for some cognitive functional impairment and bowel disturbance |

3.3. Quality of Life Measures Used

- (i)

The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal (FACT C) (version 4) quality of life questionnaire that included physical well-being, social/family well-being, emotional well-being, functional well-being, and additional concerns.

- (ii)

Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—Treatment Satisfaction–Genera (FACIT-TS-G) (version 1)

- (iii)

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC-QLQ-C30)

- (iv)

Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) (acute version)

- (v)

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC-QLQ-CR38) which is the module for colorectal cancer of the core questionnaire C30 (QLQ-C30)

One study reported that patients had a good quality of life without using/reporting a quality-of-life measure [21]. It is notable that only one of these questionnaires (CR38) is specific to a specific cancer site, in this case colon cancer, and that there are no questionnaires that have been developed for peritoneal malignancy.

3.4. Symptoms That Affect the Quality of Life of Patients with PMP

The most cited symptoms that impact the quality of life of patients with PMP (cited by 3+ papers) are abdominal distention [4, 15–18, 20, 22, 23], abdominal pain [15, 16, 18, 20, 22], malnutrition [4, 17, 19, 20, 22], fatigue [4, 8, 9, 20], physical functioning [9, 10, 19], and social functioning [9, 10, 19]. See Table 2 for the full list of symptoms/issues that affect the quality of life of patients with PMP (ranked by the number of publications).

| Preoperative | Postoperative |

|---|---|

| Abdominal distention/ascites [4, 15–18, 20–22] | Lack of energy/lethargy/fatigue/asthenia [4, 7–10, 19, 20, 22] |

| Abdominal pain [15, 16, 18, 20, 22] | Social functioning/well-being [4, 7, 9, 10, 19] |

| Nutrition/malnourished/anorexia [4, 17, 19, 20, 22] | Pain [7–9, 19] |

| Fatigue/lethargy/asthenia [4, 8, 9, 20] | Physical functioning/well-being [7, 9, 10, 19] |

| Physical functioning [9, 10, 19] | Role limitations due to physical functioning [9, 10, 19] |

| Social functioning [9, 10, 19] | Emotional functioning/emotional well-being [7, 10, 19] |

| Role limitations due to physical functioning [9, 10, 19] | Diarrhea [19, 20] |

| Role limitations due to emotional functioning [9, 10, 19] | Nausea [8, 19] |

| Weight loss/cachexia [9, 19, 22] | Vomiting [8, 19] |

| Global/general health [9, 19] | Insomnia [10, 19] |

| Body image [7, 9] | Chronic back pain [4, 20] |

| Urological problems (blood in urine/burning sensation) [9, 16] | Constipation [10, 19] |

| Nausea [8, 18] | Appetite loss [10, 19] |

| Vomiting [8, 19] | Dyspnoea (shortness of breath) [19, 20] |

| Appetite loss [10, 16] | Urination problems (frequent urination) [9, 20] |

| Anxiety/mental health [4, 9] | Global/General health [9, 19] |

| Pain [8, 9] | Cognitive functioning [10, 19] |

| Unspecific and sometimes uncommon signs and symptoms [15] | Depression, mental health [7, 9] |

| Weight gain in the abdomen associated with weight loss on arms and legs [4] | Body image [7, 9] |

| Embarrassed to go out because of abdominal distention [4] | General quality of life/global function [7, 10] |

| Dealing with the psychological impact of the disease [4] | Abdominal pain [20] |

| Constipation [10] | Dehydration [19] |

| Diarrhea [10] | Anorexia (malnutrition) [20] |

| Insomnia [10] | Inability to perform manual tasks or stand for long periods of time [4] |

| Newly onset hernia [18] | Abdominal distention/ascites [20] |

| Dyspnoea (shortness of breath) [20] | Skin fistulation [20] |

| No symptoms [22] | Role limitations due to emotional functioning [9] |

| Fever [16] | Functional well-being [7] |

| Abdominal discomfort [20] | Financial difficulties [10] |

| Pelvic pressure and gynecological complaints in females [15] | Sexual functioning/enjoyment [9] |

| Sexual functioning and enjoyment [9] | Gastrointestinal problems [4, 9] |

| Chemotherapy side effects [9] | Chemotherapy side effects [9] |

| Stoma related problems [9] | Stoma related problems [9] |

| Financial difficulties [10] | Weight loss [9] |

3.5. Synthesis of Results

One study that assessed PMP symptoms reported that the most common symptom is abdominal pain (23% of a sample of 82 patients with PMP) [18], five out of seven patients who had a major debulk surgery (incomplete surgery where surgeons were unable to remove all the disease) experienced symptom relief [22], and patients who undergo a major debulk surgery experience symptom relief over a median time of 2 years [20].

Of the included studies in this review, only five studies assessed the quality of life of patients with PMP as their main outcome [7–10, 23]. All these studies assessed PMP patients’ quality of life in relation to treatment [7–10, 23]. All studies used a validated measure of quality of life except one [21]. Some studies used retrospective data (previously collected clinical scores), and others assessed quality of life prospectively (at baseline, 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, 24 months’ postsurgery and up to 8 years’ postsurgery). Some studies were interested in specific groups: single surgery vs. redo (surgery for recurrence) [7], or complete vs major debulk [8, 20, 22].

A study that compared the quality of life of patients with PMP who had complete surgery (removed all disease) with those who had a major debulking (some disease left) found that quality of life dropped at 1-month posttreatment and returned to baseline at 3 months in both groups; however, QoL continued to improve after that only in patients who had a complete surgery [8]. A study that compared the quality of life of those who had a single surgery to those who had a redo (surgery for recurrence) reported that there was no significant difference between the two groups [7]. In both groups, quality of life was impaired between 6 and 12 months and returned to baseline levels at 12 months [7]. Two studies assessed the quality of life of patients with PMP post-CRS and HIPEC: one reported that CRS and HIPEC had “little impact” on quality of life and that quality of life returned to baseline 6 months posttreatment [9], and the second reported that patients had a good quality of life at 12 months’ posttreatment except for impairment in their cognitive function and bowel disturbances [10]. Patients who had a total gastrectomy or a total colectomy had a similar quality of life at 6 months compared to other patients [19]. In one study, 61% of the sample had a stoma, but that was found to have no influence on their quality of life [9].

4. Discussion

This is the first review of the literature on the quality of life of patients with PMP. The results show that the evidence on the quality of life of patients with PMP is limited. Only five research studies assessed quality of life in this population as a main outcome, and all five studies assessed quality of life in relation to treatment [7–10, 23]. There is no consensus on the questionnaire used to measure quality of life in this population. Five different questionnaires were used to assess quality of life in this population (FACT C (version 4), FACIT-TS-G (version 1), the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QLQ-C30, SF-36 (acute version), and the EORTC QLQ-CR38) despite the very few papers assessing quality of life in patients with PMP. A systematic review on the Qol of ovarian cancer survivors found that sixty different measures were used to assess Qol in their population [24]. There have already been calls for the standardization of the measures used to assess Qol in these populations; standardized measures will allow researchers to compare findings and reach conclusions [25].

Another important finding of this review is that quality of life in this population was mainly assessed by surgeons/surgical departments to provide evidence that the treatment (surgery) does not impair quality of life in the long term. Thus, the data on the quality of life of patients with PMP living with the disease can only be found in the data collected at baseline (pretreatment) in these studies. Patients’ quality of life at baseline/presurgery may not be representative of the quality of life of patients with PMP living with the disease. Three out of the five studies that assessed quality of life compared the quality-of-life posttreatment with baseline levels [7–9]. It is important to note that the quality of life at baseline may be impaired by the disease and that return to baseline should not be the aim for these patients. This is especially true given that the findings of this review show that little is known about the issues that affect the quality of life of patients with PMP at baseline (pretreatment). Similar to quality-of-life studies in colorectal cancer, where the majority of research gathers data of up to one year postsurgery, little is known about the long term Qol of these patients [25].

4.1. Limitations

The heterogeneity of the studies in this review makes it very difficult to make any conclusion about the QoL of patients with PMP. This review highlights how limited and varied the research on the Qol of patients with PMP currently is. Another limitation of this review is that it includes case reports [16, 17, 23], whose findings might not be generalizable. However, these studies were included because of how limited the current literature is. The inclusion criteria for this report (studies published between 2002 and 2022) may have excluded a few relevant papers; however, this review was concerned with the recent and current literature on the topic.

5. Conclusion

The current evidence on the Qol of patients with PMP is very limited. Studies that assess the quality of life of these patients independent of surgery are needed. A consensus on the measures used to assess the quality of life in this population or the development of a measure specific to this population is needed. Furthermore, studies that assess the Qol of palliative patients who receive these treatments (CRS and HIPEC) are needed.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Hampshire Hospitals NHS Foundation library staff for helping us conduct the search and retrieve the full texts for this review. This project was funded by the NIHR ARC Wessex.

Appendix

A. Search Strategy

- (1)

Pseudomyxoma

- (2)

pseudomyxoma peritonei

- (3)

PMP

- (4)

Quality of life (MeSH term)

- (5)

QoL OR Health related quality of life

- (6)

HRQOL OR Subjective health status

- (7)

Patient-reported outcome

- (8)

Patient-based outcome

- (9)

Patient-reported outcome

- (10)

Patient-based outcome

- (11)

Patient-reported outcome measure

- (12)

PROM

- (13)

Self-report

- (14)

Side effect

- (15)

Impairment

- (16)

Complaint

- (17)

Symptom

- (18)

Psychological

- (19)

Mental health

- (20)

(1 OR 2 OR 3)

- (21)

(4 OR 5 OR 6 OR 7 OR 8 Or 9 OR 10 OR 11 OR 12 OR 13 OR 14 OR 15 OR 16 OR 17 OR 18 OR 19)

- (22)

(20 AND 21)

Open Research

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.