Cancer Outpatients’ Self-Reported Pain Relief, Analgesic Adherence, and Constipation during Follow-Up Support: A Prospective, Longitudinal Study

Abstract

Aims and Objectives. This prospective study describes the pain relief, analgesic adherence, and constipation experienced by cancer outpatients with pain during the first three cycles of follow-up support based on an information system. Methods. Outpatients with cancer pain who received at least three cycles of follow-up support between 1 July 2020 and 31 March 2022 at our cancer centre were enrolled in this prospective, longitudinal study. Three cycles of follow-up support were provided by trained nurses over the telephone. Pain relief, analgesic adherence, and constipation were reported by the patients and recorded in the information system by trained nurses during the telephone follow-up. Results. A total of 386 cancer patients were enrolled in the study. Pain relief and analgesic adherence improved significantly during the three follow-up cycles after they received support (P < 0.001). The rate of pain relief and analgesic adherence improved at the second cycle compared to the first cycle, but the rate decreased at the third cycle compared to the second cycle. Some patients who had no problems at the first follow-up cycle experienced new problems during the second and third follow-up cycles. There was no significant difference in the incidence of constipation between follow-up cycles (P = 0.078). Conclusions. Cancer outpatients with pain reported increased pain relief and analgesic adherence during follow-up support. Compared to rates at the first and third cycles, pain relief and analgesic adherence were best at the second cycle after follow-up support according to the information system. Relevance to Clinical Practice. Changes in pain intensity, analgesic adherence, and constipation were noted over time, which highlights the need for continuous follow-up to achieve prolonged pain relief in cancer patients after discharge from the hospital.

1. Background

Pain is defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) as “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage” [1]. Pain is a very common distressing symptom among cancer patients, and it is generally the result of tissue damage caused by the disease and/or cancer treatment. Various systematic reviews and meta-analyses have shown that between 39.3% and 80% of cancer patients experience moderate or severe pain, respectively. The severity of pain depends on the type of cancer, stage of the disease, and treatment provided [2–4].

There were more than 19.29 million new cancer cases globally in 2020 [5], and 4.57 million new cases were diagnosed in China [6]. As a result, China has the highest number of cancer patients worldwide. However, few studies have focused on the incidence and management of pain in Chinese cancer patients due to the limited availability of accurate data. The current epidemiological data of pain in Chinese cancer patients have been collected from the acute care settings during active treatment. However, these data omit important information about the incidence of pain beyond treatment and throughout the cancer course, which makes it difficult to evaluate the true incidence of pain in cancer patients. In addition to physical burden, cancer pain is associated with increased emotional distress and depression and an association between the duration and severity of pain and the risk of developing depression has been reported [7]. Untreated pain also leads to avoidable hospital admissions, increased emergency department visits, and requests for physician-assisted suicide [8]. Therefore, pain management during and after treatment is extremely important for improving the quality of life of cancer patients.

Advances in cancer treatment have allowed more treatments on an outpatient basis [9], and more patients are living longer with the disease. Cancer pain management must be extended beyond the hospital setting. Although patients receive good pain management support in Chinese hospitals, the support provided to patients after discharge is often limited. One Chinese study showed that among 158 cancer patients living at home, 60.0% had moderate pain and 33.0% had severe pain [10]. There are a number of challenges to be addressed for effective pain management medication outside the hospital setting. Because analgesics may cause addiction and other unpleasant side effects, such as constipation, drowsiness, and nausea, access to these medications is often tightly controlled [11]. Patients and their relatives also report that the limited information provided by healthcare professionals and inadequate access to pain relief services and medications often lead to poor pain management. Some patients also report concealing pain to avoid upsetting relatives and other conflicts with family members on pain management. Patients and caregivers often report feelings of depression and hopelessness due to inadequate access to pain control in home settings [12, 13].

The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an ongoing pandemic that impacted the entire world. Cancer patients have a particularly high risk of infection due to their older age, immunosuppressive status, comorbidities, and frequent hospital admissions and visits [14, 15]. To overcome this problem, most cancer centres have had to limit the hospital visits of cancer patients to a minimum to reduce the risk of infection. Several methods have been proposed to facilitate the provision of outpatient pain management to cancer patients throughout the pandemic, including telehealth consultations [16], the referral of patients with advanced cancer to hospice care centres, and the provision of educational programs and follow-up support via phone mobile applications [11, 17]. Several recent web-based and mobile-based models of follow-up support have been developed to facilitate pain management on an outpatient basis in China. These systems typically consist of 3 main features: an information system used by healthcare professionals to provide patients with information related to pain management, an electronic pain diary for patients to report their pain, and a telephone, video or voice conferencing feature, to facilitate remote consultations. The main advantage of these systems is that they facilitate the continuous digital reporting of pain relief from a patient’s perspective. These digital data may also be used to optimise patient treatment and for research purposes [18]. However, the effect of these systems on pain management outcomes for outpatient cancer patients is not clear.

Therefore, in our centre, we developed and implemented a nurse-led follow-up information system to facilitate the pain management of cancer patients on an outpatient basis [19]. The current study describes the changes in symptoms during the first three cycles of follow-up support based on an information system: pain relief, analgesic adherence, and constipation experienced by cancer outpatients with pain.

2. Methods

The present study was performed and reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines for cohort studies. The STROBE Statement-Checklist of items is listed in Supplementary Material 1.

2.1. Research Design

2.1.1. Selection of Participants

All patients with a pathologically confirmed cancer diagnosis who were discharged from a tertiary cancer hospital were eligible to participate if they required opioid treatment for pain management and consented to participate in this study. Patients with acute pain, such as postsurgery, and patients or caregivers who could not master this follow-up information system after guidance were excluded. All patients enrolled for analysis in the study had data recorded in the follow-up information system and received at least three follow-up cycles between 1 July 2020 and 31 March 2022. All eligible patients were analysed as a cluster.

Sample size: an a priori power test was performed using GPower 3.1 [20]. An ANOVA repeated measures test was used, with α = 0.05, two tails, an effect size of f = 0.25, and a power (1 − β) of 0.99 to compute the required sample size, n = 198.

2.1.2. Ethical Considerations

The Institutional Review Board of Beijing Cancer Hospital approved this study (Approval No. 2019KT96). The nurse in charge explained the purpose of the study in detail to the patients who met the inclusion criteria. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients participating in the study.

2.2. Intervention

We developed an information system for the whole process of managing cancer patients with pain [19], which consisted of three functional modules. The personal computer (PC) in the ward was for the charge nurse to prepare for discharge, the PC in the pain clinic was for the trained nurse to provide follow-up for discharged patients, and an intelligent mobile terminal was used for the outpatients to record their pain diary and access online consultations.

2.2.1. Discharge Preparation

Patients with cancer pain received usual cancer pain management during hospitalisation [21]. During hospitalisation, patients learned to report pain intensity correctly, identify the presence of pain management-related side effects (such as constipation), determine the importance of taking analgesics correctly, and the process to seek further support. A comprehensive pain assessment was performed, and patients with pain were referred to the pain clinic via the system before discharge by a charge nurse. The patients downloaded an application developed by the hospital for registered patients to manage their pain at home, including the completion of pain diaries, online consultations, and online learning.

2.2.2. Out-of-Hospital Management [19, 21]

A trained nurse with extensive experience in pain management was a member of the multidisciplinary team (MDT) for pain management. The nurse received the patient’s information from the ward, checked the pain assessment records before discharge, and scheduled a follow-up. The follow-up content was guided by the information system, and inquiries, including pain assessment, analgesic adherence, and adverse events, were recorded by the follow-up nurse over the phone. Patients with pain intensity scores >3, as measured by the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) [22], and/or the occurrence of breakthrough pain more than 3 times in the past 24 h were scheduled for telephone follow-up within three days, and patients with stable pain control were scheduled within seven days. The nurse recorded the follow-up information in the system. The second responsibility of the nurse was to provide early warning follow-up. If the patient had an NRS score >3, had breakthrough pain more than 3 times in the past 24 h, or had a serious adverse reaction to opioids as reported in their pain diary uploaded at home, the set threshold value of early warning was activated, and an automatic reminder was sent. The nurses called the patient on time, performed a comprehensive pain assessment, identified the problems, and provided advice for pain management. After the evaluation, the nurse instructed the patient to adjust opioid analgesics after consultation with doctors from the MDT, if necessary. Third, the nurses checked the patients’ questions in the eConsult module daily, and these questions, combined with the patient’s pain diary and follow-up records, provided clear and timely answers related to pain management online.

Cancer patients with pain at home reported their pain and communicated with the trained nurse using the mobile phones. Patients with unstable pain were encouraged to write in the pain diary daily. Patients were followed up in a timely manner by the nurse when the NRS score, number of patients with breakthrough pain, and number of patients with serious adverse reactions as reported in the pain diary exceeded the warning threshold. Patients consulted nurses about pain-related problems and learned pain self-management knowledge via the application.

2.3. Measurements

The NRS assesses pain on a scale from 0 to 10. Zero represents “no pain,” and 10 represents the opposite end of the pain continuum. The NRS was used to assess the efficacy of follow-up support for pain relief. A score of three or less represented complete pain relief, and a score greater than three represented incomplete pain relief.

Compliance with analgesic treatment was measured using patient self-reports of their drug intake. The World Health Organization (WHO) adherence project has the following definition of patient compliance: “the extent to which a person’s behavior, taking medication, following a diet, and/or executing lifestyle changes corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health care provider.” [23] In this study, good compliance meant that the patient was taking the analgesic drugs as indicated, and noncompliance meant the patient did not take the analgesic drugs as indicated, such as forgetting to take the medicine, taking a lower/higher dose of the medicine than recommended, and discontinuing the medicine without orders within two weeks. The follow-up nurse asked whether the patient performed any of the aforementioned noncompliant behaviours. Patients who performed one or more of these behaviours were deemed noncompliant. Patients who took the medication as prescribed were considered compliant. The compliance results reported by patients were recorded in the follow-up information system as a single self-reported item.

Constipation was defined using the Rome IV criteria [24] as a reduced frequency of spontaneous defecation (no defecation for 3 days or more), dry stool, and difficulty in defecation, accompanied by abdominal distension and pain. The follow-up nurse questioned whether the patient experienced constipation and recorded it as yes/no in the information system. When the patient was uncertain, the nurse offered additional guidance on constipation symptoms to ensure the patient understood if they were experiencing constipation.

2.4. Data Collection

The follow-up information system exported patient follow-up records within the selected time. By reviewing the records, we identified patient clusters that met the analysis requirements for this study. The outcomes of the patients’ pain relief, analgesic adherence, and constipation, which were recorded during the telephone calls for the three follow-up cycles by the trained nurse, were retrieved from the records.

Sociodemographic and clinical data were retrieved from patient medical records.

2.5. Statistical Analyses

All statistical tests were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 19.0. The categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages, and the qualitative variables are described as the means, standard deviations (SDs), and minimum and maximum values. Repeated measures analysis of generalised estimating equations (GEE) [25] was used to examine changes in pain relief, analgesic adherence, and the incidence of constipation between the three follow-up cycles. The relationship between analgesic adherence and analgesic outcome was tested using Spearman’s test. For all statistical tests, a P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 386 patients from 26 provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions in China were included in the study. The average age was 60.24 ± 11.70 years (range: 24–88 years). Most patients were male (62.69%) and were diagnosed with lung cancer (40.42%) or gastrointestinal cancer (37.56%). The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are summarised in Table 1.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 242 | 62.69 |

| Female | 143 | 37.31 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Lung cancer | 156 | 40.42 |

| Gastrointestinal cancer | 145 | 37.56 |

| Genital and urinary system cancer | 19 | 4.92 |

| Breast cancer | 18 | 4.66 |

| Head and neck cancer | 11 | 2.85 |

| Gynaecological cancer | 5 | 1.30 |

| Others | 32 | 8.29 |

| Insurance | ||

| Free medical service | 6 | 1.55 |

| Insurance for medical service | 365 | 94.56 |

| Self-financed medical service | 15 | 3.89 |

| Districts | ||

| North China | 295 | 76.42 |

| Northeast China | 35 | 9.07 |

| East China | 27 | 6.99 |

| Central China | 14 | 3.63 |

| Southwest China | 5 | 1.30 |

| Northwest | 8 | 2.07 |

| South China | 2 | 0.52 |

3.2. Pain Relief

The rates of complete and incomplete pain relief differed significantly between the three follow-up cycles (P < 0.001) (Table 2). When incomplete pain relief was used as a reference, the partial regression coefficient of the third follow-up cycle was 0.560 greater than the first cycle, and the partial regression coefficient of the second cycle was 0.664 greater than the first cycle (P < 0.001). However, the 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) of the third follow-up cycle (95% CI, 1.406–2.180) and second follow-up cycle (95% CI, 1.572–2.400) were similar, which indicated that the difference was not statistically significant.

| Follow-up cycles | Pain relief | Analgesic adherence | Constipation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete | Incomplete | Compliance | Noncompliance | Yes | No | |

| First | 133 (34.46) | 253 (65.54) | 259 (67.10) | 127 (32.90) | 197 (51.04) | 189 (48.97) |

| Second | 195 (50.52) | 191 (49.48) | 318 (82.38) | 68 (17.62) | 181 (46.89) | 205 (53.11) |

| Third | 185 (47.93) | 201 (52.07) | 306 (79.27) | 80 (20.73) | 206 (53.37) | 180 (46.63) |

| Wald χ2 | 43.883 | 31.259 | 5.098 | |||

| P values | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.078 | |||

3.3. Compliance with Analgesic Treatment

The compliance and noncompliance rates for analgesic treatment differed significantly between the three follow-up cycles (P < 0.001) (Table 2). When noncompliance was used as a reference, the partial regression coefficient of the third follow-up cycle was 0.629 greater than the first cycle, and the partial regression coefficient of the second cycle was 0.830 greater than the first cycle (P < 0.001). However, the 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) of the third follow-up cycle (95% CI, 1.382–2.546) and second follow-up cycle (95% CI, 1.681–3.129) were similar, which indicated that the difference was not statistically significant.

3.4. Constipation

The GEE showed a goodness-of-fit of 1607.917. The incidence of constipation did not significantly differ between the three follow-up cycles (Table 2). At the first follow-up cycle, 197 patients reported constipation. The incidence of constipation decreased to 46.89% (n = 181) at the second follow-up cycle and increased to 53.37% (n = 206) at the third follow-up cycle.

3.5. Changes in Treatment Outcomes over Time

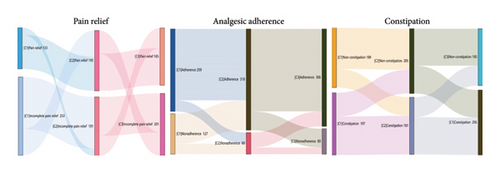

The changes in treatment outcomes over time are illustrated in the Sankey chart (Figure 1). Some patients who had effective pain relief, good compliance with analgesic treatment, and no constipation in the first follow-up cycle reported unrelieved pain, constipation, and noncompliance with analgesic treatment in the second or third follow-up cycle (Table 3).

| Follow-up cycles | Incomplete pain relief (n = 253) | Noncompliance (n = 127) | Constipation (n = 197) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decrease (n) | Increase (n) | Decrease (n) | Increase (n) | Decrease (n) | Increase (n) | |

| Second | 85 | 23 | 94 | 35 | 75 | 59 |

| Third | 63 | 75 | 47 | 59 | 63 | 88 |

3.6. The Relationship between Analgesic Adherence and Analgesic Outcome

Analgesic adherence positively correlated with pain relief (P < 0.001 or P < 0.05) in the three cycles and negatively correlated with constipation (r = −0.119, P < 0.05) in the first cycle (Table 4).

| Follow-up cycles | Pain relief | Constipation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P values | r | P values | |

| First | 0.218 ∗∗ | <0.001 | −0.119 ∗ | 0.019 |

| Second | 0.141 ∗∗ | 0.006 | −0.026 | 0.614 |

| Third | 0.107 ∗ | 0.036 | −0.099 | 0.053 |

- Note. ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗P < 0.05.

4. Discussion

Adequate pain relief in cancer patients can be challenging, especially after a patient is discharged from the hospital. A lack of professional support from healthcare professionals often leads to poor compliance with medications and difficulty in the management of drug-related side effects. To address this problem, we developed an outpatient information follow-up system to improve pain management in cancer patients. The present study evaluated the efficacy of follow-up support based on an information system for pain relief, compliance with treatment, and alleviation of adverse drug-related side effects in a cohort of 386 cancer patients following three cycles of follow-up support.

Compared to the first follow-up cycle, pain relief, analgesic adherence, and management of constipation improved considerably in the second follow-up cycle. Notably, some patients with complete pain relief, good analgesic adherence, and no constipation after the first or second cycle reported incomplete pain relief, poor analgesic adherence, and constipation in the next follow-up cycle. This finding supports the importance of ongoing follow-up support to adapt treatment plans according to patient needs, which tend to vary across disease trajectories.

Various factors may have led to the aggravation of pain during the cancer course. Opioids are the most commonly used pain control drugs for treating cancer pain. Pain management using opioids often takes time in cancer patients, and the effect can change over the course of the disease. Adherence to treatment is crucial for achieving continuous pain relief with opioids. However, some patients who achieve good pain relief stop taking the medication as prescribed, which leads to increased pain. The relationship between analgesic adherence and pain relief provided further confirmation. After prolonged administration of opioids, patients may develop tolerance, which reduces the efficacy of the treatment. Disease progression and ongoing cancer treatment may further increase pain. Therefore, dose escalation is required to achieve effective pain relief [26]. However, patients do not know how to adjust the analgesic dosage to address increasing pain. The prolonged use of opioids also increases the incidence of drug-related side effects, particularly constipation. Some patients discontinue treatment due to adverse reactions or fear that they may become addicted to medications [11]. These factors may explain the decrease in complete pain relief ratings and the increase in analgesic adherence in the third follow-up cycle compared to the second. However, there was no statistically significant difference between these two cycles.

Opioid-induced constipation is attributed to the activation of enteric μ-opioid receptors, which decrease bowel tone and contractility and increase colonic fluid absorption and anal sphincter tone while reducing rectal sensation. These changes lead to harder stools, which may be difficult to pass [27]. However, opioid-induced constipation is partially independent of the opioid dose/pathway, and disease, metabolic disorders, a sedentary lifestyle, a low-fibre diet, and medication-related factors further increase the risk of developing constipation [28, 29]. The present study found a significant correlation between analgesic adherence and constipation in the first cycle but not in the last two cycles. Constipation can be difficult to manage. Professional advice reduced the incidence of constipation at the second follow-up cycle, but the incidence of constipation increased at the third follow-up cycle. Therefore, further research is recommended to improve the management of constipation in cancer patients.

The follow-up nurses in our program played an important role in ensuring patient compliance with the pain management treatment plan and adapting the plan based on the patient’s needs. Throughout the telephone conversation, the nurses followed a protocol to ask the patient the right questions and provided advice accordingly. For example, if the nurse noted that the patient was taking the analgesic drugs at the wrong time or dose, the nurse provided instructions to enable the patient to correct and remember the correct treatment. The nurses also discussed the factors leading to noncompliance with the medication and provided patients with information to enable them to better cope with the treatment. For example, if the patient experienced adverse drug reactions, the nurse provided information on managing these reactions without stopping the pain relief medications.

The pain follow-up intervention model used in our study had several advantages compared to traditional follow-up methods. This system allowed healthcare professionals to continuously adapt pain management information according to patients’ current needs on an outpatient basis. The pain diary provided the nurses with longitudinal data, which made it easier for the nurses to adapt the treatment for the patient, especially if the patient experienced specific issues between follow-up appointments. Continuous and structured follow-up records based on the information system also provided important data for research purposes.

However, our study has some limitations that must be acknowledged. First, this study included pain management outcome data from only three follow-up cycles. Therefore, longitudinal studies are recommended to assess the efficacy of this plan in achieving pain relief and alleviating treatment-related side effects. Second, although the outcomes were obtained using structured follow-up interviews performed by nurses using the information system, the outcomes were self-reported by the patient. This reporting style creates a possibility of inaccurate answers due to personal and social concerns, which may result in self-report bias. Finally, we did not investigate specific characteristics (such as sociodemographic and clinical data) that may have contributed to the differences in the outcomes between the three follow-up cycles. However, these characteristics may be confounders and important for further understanding.

5. Conclusion

Adequate pain relief in cancer patients can be challenging, especially after a patient is discharged from the hospital. Cancer outpatients with pain reported increasing pain relief and analgesic adherence during follow-up support based on the information system. Compared to the rates at the first and third cycles, pain relief and analgesic adherence were best at the second cycle during the follow-up support based on the information system. Changes in pain intensity, analgesic adherence, and constipation were noted over time, which highlights the need for continuous follow-up to achieve prolonged pain relief in cancer patients after discharge from the hospital.

6. Relevance to Clinical Practice

Healthcare workers should pay more attention to the pain management of cancer patients after discharge from the hospital, especially for outpatients with incomplete pain relief. Long-term follow-up of cancer patients with pain is needed to improve pain relief, adherence to analgesic treatment, and management of constipation. Despite the uniqueness of each medical institution, the use of information-based systems will help strengthen the management of pain follow-up support.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Beijing Cancer Hospital (Approval No. 2019KT96).

Consent

Research assistants explained the study purpose, procedures, and participants’ role in the study to all prospective participants before they started. Patients and family caregivers were informed that the autonomy to participate or withdraw in this study at any time was respected.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest with regard to this research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ Contributions

Hong Yang, Hong Zhang, Fanxiu Heng, and Yuhan Lu conceptualized and designed the study; Xiaoxiao Ma, Shiyi Zhang, Jinxing Shao, Xin Li, and Lihua Hao performed acquisition of data and provided assistance with data analysis; Hong Yang, Hong Zhang, and Fanxiu Heng wrote the original draft, coordinated the project, and conducted data analysis; Yuhan Lu supervised, reviewed, and edited the study; Xiaoxiao Ma and Shiyi Zhang performed the tasks of methodology and consultancy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the patients who had participated in this study. The authors would like to thank TopEdit (https://www.topeditsci.com) and AJE for the English language editing of this manuscript. The research was supported by the Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Incubating Program (PX2017052) and was supported by Yuhan Lu.

Open Research

Data Availability

The datasets used or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.