Boric Acid for the Treatment of Vaginitis: New Possibilities Using an Old Anti-Infective Agent: A Systematic Review

Abstract

Introduction. Increasing microbial resistance to conventional pharmaceuticals calls for nonpharmaceutical treatments of vaginitis. This systematic review summarizes the efficacy of the antiseptic agent boric acid (BA) as a treatment option for microbial vaginitis in comparison to conventional therapies and proposes clinical recommendations. Materials and Methods. PubMed and Embase were searched for “boric acid” and “microbial vaginitis.” A protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42020160146). Inclusion criteria included clinical trials, observational and interventional studies, including case series/reports. Exclusion criteria included in vitro and animal studies, non-English language, and no BA treatment outcome. Primary outcomes included microbial, clinical, and complete cure. Secondary outcomes included adverse events, relapse/reinfection rates, evidence levels, microorganisms, treatment regimens, and follow-up time. Data were extracted to a predefined Excel sheet. Results. Of 195 identified unique articles, 54 were retrieved and 41 met our inclusion criteria. Heterogeneity precluded the conduction of a meta-analysis. Conclusion. An average cure rate of 76% was found for vulvovaginal candidiasis BA treatment. Recurrent bacterial vaginosis was controlled with BA and 5-nitroimidazole with promising results. Maintenance BA was equal to maintenance oral itraconazole therapy in vulvovaginal candidiasis and bacterial vaginosis in a retrospective study. Prolonged BA monotherapy cured three of six recurrent Trichomonas infections. Adverse events (7.3%) were typically mild and temporary. Based on our findings and the rising antimicrobial therapy resistance, we suggest intravaginal BA 600 mg/day for 2 weeks for (recurrent) vulvovaginal candidiasis and 600 mg/day for 2-3 weeks for recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Rare resistant Trichomonas infections can be treated with BA 600 mg × 2/day for months and in combination with oral antimicrobials. We suggest a maintenance regimen of BA 600 mg × 2/week for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. In case of resistant bacterial vaginosis, we suggest BA 600 mg × 2-3/week. Data on maintenance therapy and BA treatment of bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis are however limited.

1. Introduction

Vaginitis is frequently cited as the most common gynecological diagnosis in primary care, affecting most women at least once in their lifetime [1, 2]. It is associated with vaginal symptoms such as pruritis, irritation, soreness, and variable discharge [3]. Vaginitis is mostly caused by microbial infections, the most common being bacterial vaginosis (BV) which accounts for 40–50% of vaginitis cases, while vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) are found in 20–25% of cases and trichomoniasis vaginalis (TV) accounts for 15–20% of cases [3].

Vulvovaginal candidiasis affects up to 75% of women [4]. It is commonly caused by Candida (C.) albicans (up to 90%) but an increase in non-albicans Candida (NAC) species have been reported, which is often a therapeutic challenge [5, 6]. VVC is diagnosed by microscopy and cultures from symptomatic women and is often treated with topical azoles or oral fluconazole (cure 80–90%). Approximately, 5–9% of infected women will experience recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC) [7, 8], defined as three or more episodes within 12 months [9]. Maintenance fluconazole is often necessary in RVVC, but relapses are common with a rate of 30–50% over six months [4]. In addition, fluconazole-resistant C. albicans, which can develop under the selective pressure of prolonged fluconazole treatment [10], is an emerging problem [11].

Bacterial vaginosis is the most frequent type of vaginitis, characterized by a vaginal overgrowth of anaerobic bacteria that forms a biofilm on the epithelial cells [12]. Gram staining (Nugent score) and Amsel’s criteria are two common diagnostic methods in BV [13]. The standard treatment for BV is antibiotics such as oral metronidazole or clindamycin with a cure rate of 80–90%; however, a recurrence rate of 75–80% has been reported three to six months after treatment [14, 15].

Trichomoniasis is caused by the protozoa Trichomonas vaginalis (TV), accounting for 15–20% of vaginitis cases [16]. TV can be diagnosed microscopically, but a higher sensitivity is found in nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) and cultures [17]. It is treated with 5-nitroimidazoles, with cure rates of 84–100%, but reinfections are common as 17% experienced reinfection within 3 months in one study [4, 18].

An increase in resistant species or selection of NAC species in VVC is linked to excessive exposure to antimycotic drugs, and high recurrences of BV are thought to be caused by antibiotic resistance due to polymicrobial biofilm and acquired resistance genes [19]. In TV infections, resistance also plays a role with metronidazole resistance varying from 4% in the US to 17% in Papua New Guinea [20, 21].

Intravaginal boric acid (BA) is a nonpharmaceutical antiseptic agent first shown to be effective in treating mycotic vaginitis in 1974 by Swate and Weed [22]. It has been used to treat VVC, BV, and TV, especially in case of recurrences [23, 24]. Unlike antibiotics and antimycotics, BA affects a broad spectrum of biologic processes in microbes, including inhibition of NAD-dependent enzymes in mitochondria and inhibition of hyphal growth [25], and in vitro studies have recently shown BA inhibition of biofilm production in bacteria and fungus [26, 27]. One in vitro study has shown that BA is microbicidal against TV independent of pH [28]. These mechanisms make resistance development more unlikely against BA as compared to conventional therapies [25].

The emergence of resistance and selection of species with low susceptibility to conventional therapy as well as the potentially lower risk of systemic adverse effects would theoretically make BA an ideal treatment option for vaginitis.

This review aims to summarize the efficacy of BA in patients with VVC, BV, and TV, compared to conventional therapies, to investigate whether BA is superior to other treatment options or has a lower recurrence rate, and lastly to make clinical recommendations for the use of BA in acute and recurrent microbial vaginitis.

2. Methods

2.1. Search String

This systematic review is reported in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines [29]. A protocol was sent to Prospero on November 29th, 2019, with ID number CRD42020160146 and was registered on July 10th, 2020. The databases PubMed and Embase were searched for vaginitis and boric acid. The following search string was chosen: (“Vaginitis” [Mesh] OR (“vaginitis” [MeSH Terms] OR “vaginitis” [All Fields])) AND ((“Boric Acids” [Mesh] OR (“boric acid” [Supplementary Concept] OR “boric acid” [All Fields])) OR (“boric acids” [MeSH Terms] OR (“boric”[All Fields] AND “acids”[All Fields]) OR “boric acids”[All Fields])). There were no restrictions on the publication year. Two authors conducted the literature search screening independently using the literature search tool Rayyan [30] on April 8th, 2020, in order to find all eligible papers, and later updated on October 30th 2023. When any disagreements occurred, the authors would assess the eligibility of the paper together.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

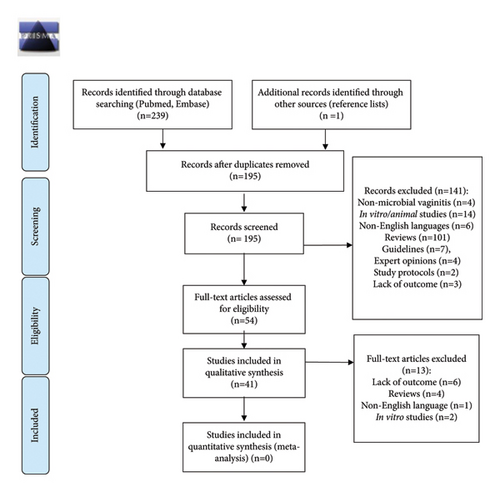

Inclusion criteria included randomized and nonrandomized clinical trials, observational and interventional studies, including case series and case reports assessing BA for the treatment of microbial vaginitis. Case reports and case series were included since only case reports described trichomoniasis treated with BA. Exclusion criteria included in vitro studies, animal studies, non-English language articles, reviews, guidelines, and expert opinions. Articles without a BA treatment outcome were also excluded. The reference lists were manually checked for further eligible studies. A PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) provides additional details of the literature search and exclusions.

2.3. Data Extraction and Outcomes

All relevant data from the included studies were extracted to a predefined Excel sheet and the data were afterwards checked by two authors (MLM and DMS). Primary outcomes were microbial cure, clinical cure, and complete cure (in % of patients). Complete cure was defined as a simultaneous microbial and clinical cure. Outcome averages have been calculated as a summary measure.

Secondary outcomes were adverse events, relapse/reinfection rates, evidence levels, microorganisms, treatment regimens, and follow-up time. Adverse events were defined as all events mentioned in the included studies. The evidence levels were classified in accordance with the evidence quality grading recommendations published by the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) [32] (Table 1). If no data were available, this was stated as not available (NA). No risk of bias tools was applied. The outcome was reported as microbial, clinical, or both (complete cure). One article reported the outcome as patients’ satisfaction with BA maintenance therapy [33].

| Level A | The highest level of evidence, which includes systematic reviews and meta-analysis, randomized controlled trials with consistent findings, and all-or-none observational studies |

| Level B | An intermediate level of evidence, which includes systematic reviews and meta-analysis of lower quality, clinical trials or studies with limitations and inconsistent findings, lower quality clinical trials, cohort studies, and case-control studies |

| Level C | The lowest level of evidence, which includes consensus guidelines, usual practices, expert opinion, case series, and case reports |

- Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) evidence quality grading recommendations [32].

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search

A total of 239 articles were identified through PubMed (n = 87) and Embase (n = 152) databases. In addition, one article was identified via references. After removing duplicates, a total of 195 unique articles were skimmed and 141 articles were excluded. The remaining 54 articles were examined by abstract and text and 13 articles were excluded based on the exclusion criteria. Finally, 41 articles were included in this systematic review.

3.2. Heterogeneity of Studies

The 41 eligible articles consisted of two double-blinded randomized controlled trials (RCTs), two open-label RCTs, four prospective studies of which three were open label studies and one was observational, 10 retrospective studies, and 19 case reports. In addition, one article [34] was a follow-up on an open label RCT (Table 2). Finally, three studies containing case descriptions were included in the case report table making a total of 22 case reports (Table 3). A total of 27 articles studied the use of BA in VVC, four in BV or concomitant BV and VVC, and 10 articles in TV, respectively.

| References | Diagnosis | Study type (evidence level) | Number of patients (BA treated/total number) | Mean age (range) median when stated | Microbial confirmation | Microorganisms | Intravaginal BA treatment regimens and other treatments | Main-tenance BA yes/no | Follow-up | Microbial cure | Clinical cure | Complete cure | Side effects n/total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vulvovaginal candidiasis | |||||||||||||

| Jovanovic et al. [35] | Chronic VVC included after failing initial treatment | Open label prospective study (B) | n = 92/92 | 35 years (NA) | Yes (M) | Microscopic chronic fungal findings |

|

Yes | 6-months | 78/92 (85%) P-value (NA) | NA | When long-term maintenance patients are counted: BA: 90/92 (98%) P value (NA) | Temporary burning sensation: 4/92 (4.3%) |

| Swate and Weed [22] | VVC/RVVC | Open label prospective study (B) | n = 40/40 | 32.7 years (NA) | Yes (M) |

|

|

No |

|

|

NA | NA | Temporary burning sensation + watery discharge: 3/40 (7.5%) |

| Nyijesy et al. [36] | RVVC/chronic VVC | Prospective observational study (B) | n = 13/74 | 38.5 years | Yes (M and C) | C. albicans (68%), non-C. albicans (32%): C. glabrata (16%), S. cerevisae (6%), C. parapsilosis (5%), and NA (5%) |

|

No | Shortly after therapy ended |

|

NA | NA | NA |

| Guaschino et al. [37] | RVVC | Prospective nonrandomized study (B) | n = 11/22 | 30 years (NA) | Yes (C) | C. albicans (91%) and C. glabrata (9%) |

|

Yes |

|

|

|

NA | |

| Khameniae et al. [38] | VVC | Cross-sectional, randomized, double blind study (double blind RCT) (A) | n = 75/150 | 30 years (18–45) | Yes (M and C) | Symptomatic Candida vaginitis (NS) |

|

No |

|

|

|

No side effects | |

| Marchaim et al. [11] | RVVC resistant C. albicans | Retrospective cohort study (B) | n = 25/25 | 43 years (NA) | Yes (C) | Fluconazole resistant C. albicans |

|

Yes | NA | Initial BA therapy in most patients with fluconazole resistant C .albicans before maintenance therapies: invariable mycologic eradication | NA |

|

NA |

| Powell et al. [5] | VVC Non-C. albicans included | Retrospective observational study (B) | n = 66/108 | Approx. 45.8 years (NA) | Yes (M,C) |

|

|

No | Typically 2–4 weeks after treatments |

|

Clinical cure: all patients retrospectively determined to have non-C. albicans causing symptoms achieved clinical cure | NA | NA |

| Ray et al. [39] | Diabetes and VVC | Randomized, controlled, open label study (open label RCT) (B) | n = 50/111 | 40 years (29–51) | Yes (M and C) |

|

|

No |

|

|

NA | NA | Temporary burning sensation: 2/56 (3.6%) |

| Ray et al. [34] | VVC follow-up on patients with diabetes and VVC | Follow-up on open label RCT (B) | n = 19/40 | 37.4 years (±10.4) | Yes (C) | NA |

|

No | This paper is a follow-up study |

|

NA | NA | NA |

| Sood et al. [40] | VVC patients with non-C. albicans and terconazole regimen included | Retrospective study (B) | n = 10/25 | Median: 45 years (17–78) | Yes (M and C) |

|

|

No | Right after treatment 1 month |

|

NA | NA | NA |

| Sobel and Chaim [41] | VVC patients infected by C. glabrata with symptoms included | Retrospective study (B) | n = 26/75 | NA (NA) | Yes (M and C) | C. glabrata |

|

Yes | NA |

|

|

|

Burning sensation: 1/26 (3.8%), diffuse erythema 1/26 (3.8%), erosive changes to vulva (after laser) 1/26(3.8%). Total: 3/26 (11.5%) |

| Sobel et al. [42] | VVC/RVVC patients with C. glabrata infections and multiple azole treatment failures included | Retrospective case series (B) | n = 111/141 | Detroit: Median 41 (16–70) Beer Sheba: median 31 years (NA) | Yes (M and C) | C. glabrata |

|

No | NA |

|

NA | NA | Vaginal burning sensation: <10% |

| Van Slyke et al. [43] | VVC | Double blind comparative study (double blind RCT) (A) | n = 62/108 | 21.5 years (NA) | Yes (M and C) | C. albicans |

|

No | 7–10 days 30 days |

|

NA | NA | Slight watery discharge in most women and no other side effects |

| Nyirjesy et al. [44] | RVVC: patients with C. parapsilosis cultures and chronic symptoms were included | Retrospective observational study (B) | n = 6/51 | Median: 46 (19–86) | Yes (M and C) | C. Parapsilosis |

|

No | 1–4 months after species identification |

|

NA | NA | NA |

| File et al. [45] | RVVC: fluconazole-resistant C. albicans | Retrospective study (B) | n = 58/71 | NA | Yes (M and C) | C. albicans | BA: 600 mg for a minimum of 14 days (n = 58) |

|

|

|

NA | NA | |

| Bacterial vaginosis | |||||||||||||

| Reichman et al. [46] | rBV | Retrospective study (B) | n = 58/58 (60 episodes) | 33 years (NA) | Yes (A) | NA |

|

No |

|

NA |

|

NA | No side effects |

| Bacterial vaginosis and concomitant vulvovaginal candidiasis and bacterial vaginosis | |||||||||||||

| Surapaneni et al. [47] | RBV | Uncontrolled retrospective cohort study (B) | n = 105/105 | 36.6 years (18–60) | Yes (A) |

|

No |

|

NA | NA |

|

No adverse events (0/69) | |

| Powell et al. [33] | RBV/RVVC | Retrospective study (B) | n = 78/78 | 40 years (NA) | NA (NA) | NA |

|

Yes | NA | NA | NA |

|

|

| Marazzo et al. [48] | BV/VVC | Phase 2 randomized investigator blind study (open label RCT) (B) | n = 88/106 | 31 years (NA) | Yes (A, M, C, and NS) | VVC majority: C. albicans |

|

No |

|

|

|

NA | Temporary burning sensation: 10/104 (9.6%.). Headache 2/104 (2%). Pruritis: 7/104 (7%). Total: 19/104 (19%) No one stopped treatment |

- Diagnostic method: microscopy (M), culture (C), Amsel’s (A), NAAT (N), and Nugent score (NS). VVC = vulvovaginal candidiasis. BV = bacterial vaginosis. RVVC = recurrent VVC. RBV = recurrent BV. C. = Candida. NA = not available; NS = not specified; n = number. PO = per orale. Evidence level A: the highest level of evidence, which includes systematic reviews and meta-analysis, randomized controlled trials with consistent findings, and all-or-none observational studies. Evidence level B: an intermediate level of evidence, which includes systematic reviews and meta-analysis of lower quality, clinical trials, or studies with limitations and inconsistent findings, lower quality clinical trials, cohort studies, and case-control studies. Level C : the lowest level of evidence, which includes consensus guidelines, usual practices, expert opinion, case series, and case reports [32]. ∗EDTA-enhanced BA.

| References | Diagnosis | Number of patients | Microbial confirmation | Species | Treatment regimens | Monotherapy success yes/no | Polytherapy success yes/no |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vulvovaginal candidiasis | |||||||

| Baum and Morris [49] | RVVC | 1 | Yes (C) | C. glabrata | BA: 600 mg/day for 7 days | No | NA |

| Savini et al. [50] | RVVC | 1 | Yes (M and C) | C. glabrata | BA: 600 mg/day for 14 days | Yes | NA |

| Dhingra and Roseblade [51] | RVVC | 1 | Yes (C) | C. glabrata | BA: 600 mg/day for 14 days | Yes | NA |

| Nichols and Silverman [52] | RVVC | 1 | Yes (M and C) | C. lusitaniae | BA: 600 mg/day for 14 days | Yes | NA |

| White et al. [53] | RVVC | 3 | Yes (M and C) | C. glabrata | Patient 1: BA: 600 mg/day for 14 days | No | NA |

| Patient 2: BA: 600 mg/day for 14 days | No | ||||||

| Patient 3: BA: 600 mg/day for 14 days | No | ||||||

| White et al. [54] | RVVC | 1 | Yes (M and C) | C. glabrata | BA: 600 mg 2×/day for 14 days | No | NA |

| Carey et al. [55] | VVC | 1 | Yes (C) | P. lilacinus | BA gel: NA | No | NA |

| Shinohara et al. [56] | VVC | 1 | Yes (C) | C. krusei and C. glabrata | BA: 600 mg 2×/day for 10 days | Yes | NA |

| Sobel et al. [57] | VVC | 1 | Yes (M and C) | C. albicans—fluconazole resistant | BA: 600 mg 2×/day for 14 days | Yes | NA |

| Redondo-Lopez et al. [58] | VVC | 1 | Yes (M and C) | C. glabrata | BA: 600 mg 2×/day | Yes | NA |

| Sobel et al. [59] | RVVC | 2 | Yes (M and C) | Case 5: S. cerevisiae | Case 5: BA 600 mg/day for 7 days + ketoconazole 400 mg/day | NA | Yes |

| Case 9: S. cerevisiae + C. glabrata | Case 9: BA 600 mg/day (duration NS) to cure C. glabrata. After maintenance: 600 mg 2×/week. During maintenance: S. cerevisiae infection: 600 mg 2×/day. After maintenance: 6 months | Yes | NA | ||||

| Makela et al. [60] | VVC | 1 | Yes (M and C) | T. inkins | BA: 600 mg/day for 14 days | Yes | NA |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | |||||||

| Biagi et al. [61] | rTV metronidazole allergic | 1 | Yes (N) | Trichomonas vaginalis | 1: Metronidazole treatment failed due to unsuccessful desensitization | No | NA |

| 2: BA 600 mg daily for 14 days | |||||||

| 3: Prolonged BA treatment failed due to vaginal bleeding | |||||||

| 4: Tinidazole | |||||||

| Butt Saira et al. [62] | rTV multidrug failure | 1 | Yes (M, C, and N) | Trichomonas vaginalis | 1: Treatment failure with BA 600 mg/day 90 days | No | Yes |

| 2: Cure: intravenous metronidazole 500 mg every eight hours 7 days + oral liquid tinidazole 2 g daily + BA 600 mg daily for 14 days | |||||||

| Salas et al. [63] | TV nitroimidazole resistance | 1 | Yes (M and N) | Trichomonas vaginalis | Oral tinidazole 3× daily for 14 days + BA 600 mg 2× daily for 28 days | NA | Yes |

| Aggarwal et al. [64] | rTV metronidazole allergic (case 1), resistance (case 2) | 2 | Yes (M and C) | Trichomonas vaginalis | Case 1: BA 600 mg/day alternating nightly with clotrimazole intravaginally 5 months. Remained cured for over 5 years | NA | Yes |

| Case 2: BA 600 mg 2× daily for 1 month + gentian violet 1× weekly. Microbiologic cure over 4 months | Yes | ||||||

| Muzny et al. [65] | TV nitroimidazole allergic | 1 | Yes (M and C) | Trichomonas vaginalis | BA 600 mg 2×/d for 14 days. Reinfection after 2 weeks: BA for 2 months. Microbiologic and symptomatic cure achieved. Was still cured at 60 days follow up | Yes | NA |

| Backus et al. [66] | rTV metronidazole allergic | 1 | Yes (M and N) | Trichomonas vaginalis | BA 600 mg/day for 45 days. New symptoms 2 months after: BA 600 mg 2×/day for 60 days | Yes | NA |

| Diddle [67] | rTV metronidazole resistant | 1 | Yes (M) | Trichomonas vaginalis | Devegan ∗∗ intravaginally 2/day for a total of 105 days | NA | Yes |

| Seyedroudbari et al. [68] | rTV Multidrug failure and nitroimidazole intolerance | 1 | Yes (M and N) | Trichomonas vaginalis | 1: BA and metronidazole, as well as BA and tinidazole, stopped due to intolerance | Yes | No |

| 4: BA monotherapy 600 mg intravaginally 2×/day for 3 months resulted in cure | |||||||

| McNeil et al. [69] | TV nitroimidazole resistance | 1 | Yes (M and C) | Trichomonas vaginalis | 1: Monotherapy BA 600 mg 2×/day | No | Yes |

| 3: oral secnidazole + BA 600 mg 2×/day for 14 days resulted in cure | |||||||

| Edwards et al. [70] | TV nitroimidazole resistance | 1 | Yes (M and P) | Trichomonas vaginalis | 1: BA 600 mg 2×/day for 60 days + clomitrazole vaginal cream resulted in cure | NA | Yes |

- BA = boric acid; TV = Trichomonas vaginalis infection; VVC = vulvovaginal candidiasis; rTV = recurrent Trichomonas vaginalis infection; RVVC = recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis; NS = not specified; NA = not available; diagnostic methods: microscopy (M), culture (C), NAAT (N), and PCR (P). Microorganisms: C. = Candida, P. = Paecilomyces, S. = Saccharomyces, and T. = Trichosporon. ∗∗contains acetarsone, BA, and hydrolyzed carbohydrates.

The follow-up time varied from no follow-up to 12 months. BA was administered intravaginally as a powder in a suppository with concentrations of 250–600 mg. The treatment regimen varied from 250 to 1200 mg per day, for seven days to five months.

3.3. Clinical Entities Studied

The following species were identified in VVC (Tables 2 and 3): C. glabrata (syn. Nakaseomyces glabrata) (n = 394), C. albicans (n = 344), C. parapsilosis (n = 80), C. tropicalis (n = 10) C. lusitaniae (syn. Calvispora lusitaniae) (n = 7), C. krusei (syn. Pichia kudriavzevii) (n = 3), Trichosporon (T.) inkins (n = 1), Saccharomyces (S.) cerevisiae (n = 5), Paecilomyces (P.) lilacinus (n = 1), C. glabrata and S. cerevisiae (n = 1), and C. krusei and C. glabrata (n = 1).

Eleven Trichomonas infections were identified (n = 11). In the rest of the infections, identification of species level was not available or unclear, including all BV studies (n = 596).

3.4. Vulvovaginal Candidiasis

3.4.1. BA Monotherapy

Two prospective studies by Jovanovic et al. (n=92) and Swate et al. (n=40) investigated the efficacy of BA 600 mg twice daily for 14 days in treatment naive or antimycotic failure patients (Table 2) [22, 35]. In the study by Jovanovic et al. which focused on chronic VVC, maintenance BA therapy was then performed on 38 out of 92 patients, corresponding to 600 mg BA once daily following four menstruation cycles. No data on the fungal species were available. Microscopic cure was present in 85% of patients at 6 months follow-up [35]. In the study by Swate and Weed, C. albicans was present in 93% of samples, while the remaining samples were not specified. Microscopic cure was observed in 95% of patients at 30 days follow-up [22, 35].

3.4.2. BA Compared to Oral Fluconazole in C. albicans versus C. glabrata in Patients with Diabetes

One open-label RCT by Ray et al. (n = 111) [39] found no significant difference between BA 600 mg daily for 14 days (cure rate of 74%) compared to a single 150 mg-dose fluconazole (cure rate of 51%) at 15 days follow-up (Table 2) when treating women with diabetes and either C. albicans or C. glabrata infections (p = 0.07). However, when only C. glabrata infections were analyzed, BA achieved a significantly higher cure rate (72%) compared to fluconazole (33%) (p = 0.01) [39].

3.4.3. BA Compared to Other Antimycotic Treatments

In a double blind RCT study, Van Slyke et al. [43] compared BA 600 mg daily with intravaginal nystatin for 14 days in patients with C. albicans infections (n = 108) and found no significant difference at 30 days follow-up. In a prospective study by Guaschino et al. (n = 22) [37], the efficacy of BA maintenance therapy was compared with itraconazole maintenance therapy in patients with C. albicans and C. glabrata RVVC with no significant difference at 30 days follow-up (Table 2).

3.4.4. Non-albicans Species and Azole-Resistant C. albicans

Five retrospective studies investigated BA efficacy in NAC species [5, 36, 40–42, 44] as well as one observational study.

Three studies investigated C. glabrata infections as well as other NAC species. In a study by Powell et al., 600 mg BA for 21–30 days cured 45 of 56 patients with NAC infections (80%). Specifically, the cure rate for C. glabrata infections was 32/41 (78%). Fluconazole cured 3 of 5 patients with C. glabrata (60%) and 13 of 16 patients with C. parapsilosis (81%). Follow-up was typically 2–4 weeks after treatment [5]. Sobel et al. included patients with nonazole-sensitive C. glabrata infections. In 111 patients, BA 600 mg/day for 14–21 days cured 74 of 111 patients (67%). They found no difference in the 14- and 21-day regimen. Topical flucytosine cured 27 of 30 patients (90%) that initially failed antimycotic and BA therapy. The follow-up period was not stated [42]. In another retrospective study, Sobel and Chaim included patients with symptomatic C. glabrata infections. BA 600 mg/day for 14 days cured 21 out of 26 patients (81%). Other types of antimycotic therapies, including azoles and topical flucytosine, cured 12 of 31 patients (39%). No information on the follow-up length was available [41].

Nyirjesy et al. investigated resistant C. parapsilosis infections in a retrospective study. BA 600 mg 2×/day for 14 days cured 6 of 6 patients (100%). Azoles were used in 27 patients with a cure in 25 patients (93%). Follow-up were 1– 4 months after treatments [44]. In a retrospective study by Sood et al., terconazole was used as treatment of patients with NAC infections with a 1-month cure rate of 14 of 25 patients (44%). BA was used for ten of the therapy failures with a cure in 4 patients (40%), but the length and doses were not described [40]. Finally, one observational study by Nyirjesy et al. investigated both NAC and azole-resistant C. albicans [36]. BA 600 mg 2×/day for 14 days cured 11 of 13 patients (85%) with NAC infections, while azoles cured 9 of 21 (43%). When specifically focusing on fluconazole, the cure rate was 2 of 8 patients (25%). This was significantly different from the cure rate in C. albicans-infected patients, where the cure rate was 51 of 51 patients (100%) (p < 0.001) [36].

The average BA microbial cure rate in NAC infections was 72% (range 40–100%) [5, 36, 40–42, 44].

Two articles investigated azole-resistant C. albicans infections [11, 45]. Marchaim et al. investigated fluconazole-resistant C. albicans infections (n = 25) [11], and most patients were initially treated with BA 600 mg per day for 14 days which invariably resulted in cure (cure rate NA) (Table 2). Subsequently, three out of four patients with high level azole resistance to multiple drugs were successfully controlled with BA maintenance therapy of 600 mg three times a week. In another retrospective study, File et al. also investigated fluconazole-resistant C. albicans infections (n = 71). In total, 58 patients received 600 mg BA per day for 14 days, and 38 patients returned for follow-up after 7 days, with a mycologic cure rate of 28 out of 38 patients (74%). Ten other patients had a later unspecified follow-up with a mycologic cure rate of 10 of 10 patients (100%) [45].

3.5. Bacterial Vaginosis

3.5.1. BA Addition to Antimicrobial Therapy

In a retrospective study by Reichman et al. [46], the addition of BA to an antimicrobial therapy regimen for recurrent BV (RBV) (n = 58) was investigated (Table 2). Patients were treated with oral nitroimidazole for seven days followed by intravaginal BA 600 mg daily for 21 days. Cure rates were 92% at seven weeks, and 88% at 12 weeks, before a topical metronidazole maintenance for 16 days was initiated in most patients (n = 50). A failure rate of 45% and 50% was documented after 32 and 36 weeks, respectively [46]. In another retrospective study by Surapaneni et al. [47], BA was also added to a nitroimidazole regimen in recurrent BV patients (n = 105). Patients were treated with nitroimidazole 500 mg 2×/day for 7 days with a simultaneous intravaginal BA 600 mg/day for 30 days and a maintenance metronidazole gel was thereafter prescribed twice weekly for 5 months. Cure rate at first follow-up visit after intravaginal BA at day 32 was 92 out of 93 patients (99%) and 48 out of 69 (70%)at 6 months.Along-term cure rate of 20 out of 29 patients (69%) was observed at 12 months. The authors compared the early remission with a nitroimidazole-only therapy in which only 42% (36/85) women with recurrent BV had remission at 30 days. The combined nitroimidazole and boric acid remission rate of 99% was significantly higher (odds ratio 124 (95% confidence intervals 17; 930)).

3.5.2. Enhanced BA Efficacy in BV, VVC, and Concomitant BV and VVC

Marrazzo et al. [48] investigated TOL-463 (EDTA-enhanced BA) to treat VVC and BV in an open label RCT (n = 106) (Table 2). They compared a gel (BA 250 mg) to an insert (BA 500 mg) 7-day application. The insert version resulted in a clinical cure rate of 59% in BV and 92% in VVC, while the gel version resulted in a cure rate of 50% in BV and 81% in VVC at day 9–12. Out of eight patients with a documented concomitant BV and VVC infection, two patients were cured of both infections. At the last day of treatment, symptom resolution was reported in 88% and 93% for BV subjects, and 69% and 85% for VVC subjects in the gel and insert group, respectively. In 58% of BV patients in the gel group and 41% of the insert group, additional treatment was prescribed.

3.5.3. Maintenance BA

One retrospective study by Powell et al. [33] analyzed the clinical use of BA maintenance therapy in patients with recurrent infections of BV (n = 33), VVC (n = 35) or concomitant BV, and VVC (n = 10). Most patients (74.4%) had an induction regimen of BA before starting the maintenance regimen, while 27 patients received antimycotic or antibacterial drugs initially, most often in BV (n = 15). The maintenance treatment regimen was BA 300–600 mg 2-3 times per week with an average treatment duration of 13.3 months. However, BV patients had an average of 17 months treatment. Patient satisfaction was defined as satisfied, partly satisfied, or not satisfied, based on clinical documentation and 77% of patients were deemed “satisfied.”

3.6. Trichomoniasis

The use of BA to treat trichomoniasis was solely described in case reports (Table 3).

The patients were either allergic to 5-nitroimidazoles (n = 5) or experienced resistant TV (n = 6). BA was used as a monotherapy in a total of six patients, with treatment success in three out of six patients (50%) [35, 61, 65, 66, 68, 69]. Seven out of eight patients were cured with a combination of BA and other drugs including two patients that failed BA monotherapy [62–64, 67–70].

3.7. Monotherapy Treatment Regimens

The most common monotherapy treatment regimen in VVC patients was BA 600 mg daily for 14 days with a microbial cure of 231 out of 308 patients (75%) in 10 articles. Another commonly used regimen was BA 600 mg twice daily for 10–14 days with a microbial cure of 138 out of 155 patients (89%) in eight articles (Table 2).

One study by Khameneie et al. [38] and one case report [49] used 600 mg daily for seven days in VVC patients with a cure rate of 47% in the first study while the case report did not end in cure. Guaschino et al. [37] used 300 mg for 14 days (one month microbial cure rate: 91%), while Powell et al. [5] used 600 mg for 21–30 days (cure rate 80%).

In trichomoniasis, three patients were cured with a BA monotherapy and all received BA 600 mg twice daily. Two patients achieved cure after approximately two months, while the last patient achieved cure after three months [65, 66, 68].

3.8. Adverse Events

A common adverse effect reported was temporary vaginal burning in 6 studies (36/709, 5%) (Table 2). Other adverse events such as pruritis, erythema, vaginal bleeding, and erosive changes were also described in a few instances (16/709, 2.3%) [41, 48], making a total of 52 out of 709 (7.3%) adverse events. No data were available in 189 out of 906 patients (21%). Watery discharge was described as a common and mild adverse event in two studies, but the frequency is unclear [22, 43].

4. Discussion

BA is an old anti-infective agent which may still be useful in some situations even though it may be difficult to obtain in some countries (Table 4). BA capsules can be prescribed as a magistral formulation.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Nonpharmaceutical treatment options with no risk of developing or selection of azole resistance | Not available as a standard treatment in all countries |

| Low risk of interaction with systemic drugs | Not recommended in pregnant and lactating women |

| Effective in all Candida species including C. glabrata | Potentially more costly than antimicrobial therapy |

| Difficult to access in some countries | |

It has been found to be equally effective as fluconazole and itraconazole as monotherapy in selected studies [37–39] and significantly superior to nystatin, as well as fluconazole in C. glabrata infections [39, 43]. Fifteen articles and twelve case series/reports investigated the use of BA in VVC infections with a microbial cure rate average of 76% (range 40–100%) as compared with a 61% average (range 25–100) when using antimycotic medication (Table 2). When specifically summarizing microbial cure rates in NAC infections, BA had a microbial cure rate average of 72% (range 40–100%) [5, 36, 39–42, 44], as compared to a 56% fluconazole (range 25–89%) [5, 36, 39, 41, 44], and 54% nonfluconazole azole (range 38–100%) cure rate, respectively [5, 40, 41, 44]. Lower cure rates to antimycotic treatments were expected in NAC species, which are known to be less sensitive to azoles [4, 71].

For acute VVC and VVC due to C. albicans with mild symptoms, primarily local treatment should be administered, and for severe symptoms of VVC, oral azole antifungals should be applied [72]. However, C. albicans infections have also recently demonstrated increasing fluconazole resistance [71] which has been found to be associated with low doses of weekly fluconazole therapy (P = 0.03) [11].

In order to prevent fluconazole resistance in fluconazole susceptible Candida species or the selection of Candida species with initial fluconazole resistance (e.g., C. glabrata and C. krusei), and considering the relatively low adverse effect rate of 7.3% in treated patients as shown in this systematic review, we recommend the use of intravaginal BA treatment for recurrent infections and NAC infections (Table 5). Sobel et al. recommend vaginal application of 600 mg BA suppositories for 14 days of C. glabrata, while others recommend topical flucytosine [42]. Furthermore, topical applied treatment has a lower risk of systemic adverse events and drug-drug interaction.

| 1st choice therapy | 2nd choice when treatment failure on conventional therapy | Treatment regimen (intravaginal) | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candidiasis | ||||

| VVC | + | + | BA 600 mg × 1 daily for 2 weeks | 1st choice therapy: when C. glabrata or azole-resistant VVC |

| 2nd choice therapy: when treatment failure after fluconazole therapy for a minimum of 6 months | ||||

| RVVC | + | + | Initial: BA 600 mg × 1 daily for 2 weeks | 1st choice therapy: when intention is to avoid azole resistance |

| Maintenance: BA 600 mg × 2/week | Maintenance: 2nd choice: consider evaluation monthly. Data on maintenance are limited | |||

| Vaginitis | ||||

| BV | — | + | Initial: BA 600 mg × 1 daily for 2-3 weeks | Only for resistant cases |

| Maintenance: BA 600 mg × 2-3/week | Maintenance: data on maintenance are limited | |||

| TV | — | + | Initial: BA 600 mg × 2 daily for months | Only for resistant cases or in selected cases of nitroimidazole intolerance |

| Maintenance: no data | Optionally in combination with oral metronidazole or tinidazole (data sparse) | |||

- BA: boric acid; VVC: vulvovaginal candidiasis; BV: bacterial vaginosis; TV: Trichomonas vaginalis; RVVC: recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis; C.: Candida; +: yes, support use; —: no, not recommendable.

BA has seemingly been used to treat BV for years [43] but only four articles were found to investigate the effect of BA in BV either in combination with nitroimidazole or in cases with a concomitant BV and VCC infections [33, 46–48]. Therefore, it is difficult to evaluate the individual effect of BA, and further studies are needed. Two studies added BA to a nitroimidazole regimen, which seemed effective when evaluating early remission rates at 30 days and 7 weeks (99 and 92%, respectively) [46, 47]. It was not possible to differentiate between relapse and reinfections in RBV. BA was also used as maintenance therapy [33] in BV patients in another study which also seemed to be beneficial to RBV patients although the only available outcome was self-reported satisfaction (77% satisfaction). An advantage of BA is also the antimycotic effect that decreased the risk of secondary VVC infections. When treatment failure on conventional therapy occurs, BA might be useful in these patients in combination with nitroimidazole. However, the current evidence is very limited.

BA for the treatment of trichomoniasis was only described in eleven individuals with 5-nitroimidazole intolerance (n = 6) or resistance (n = 5) (Table 3). Optimal treatment regimen for BA monotherapy is unclear in TV patients, but based on these case reports, it appears to require up to several months of high dose intravaginal BA to clear a TV infection. BA monotherapy was unsuccessful in one individual with a regimen of 600 mg daily for 90 days [62], while 600 mg twice daily resulted in cure in three individuals [65, 66, 68]. Thus, a dose-dependent response looks reasonable, as proposed by Thorley and Ross [24]. When bearing in mind that TV infections are normally treated with systemic antibiotics, it is apparent that a topical antiseptic agent such as BA has its limitations. However, these cases suggest BA as an alternative treatment option in rare cases of persistent TV infections due to resistance to nitroimidazole or for patients with nitroimidazole allergy or intolerance, drug-drug interactions, or other contraindications. Combinational therapy of BA and another drug could potentially prove more useful than BA monotherapy, as seven out of eight individuals described in this review were cured with a combination of BA and other drugs, but this should be further investigated.

It is noticeable that five studies and one case report mention the use of a maintenance BA therapy in patients with recurrent BV and VVC [11, 33, 35, 37, 41, 59]. Maintenance BA was equally effective as compared to oral itraconazole maintenance therapy [33] and retrospective data on maintenance use of BA in RVVC and RBV up to more than three years resulted in high patient satisfaction (77%) with few adverse events [33]. These findings indicate that BA could be beneficial as a maintenance therapy in RVVC and RBV, but more studies are needed.

BA is known for its antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral activities and its antiseptic and astringent characteristics, poisoning is rare, and it is generally of low oral toxicity after acute oral ingestion in humans [73]. However, while it has been shown to be beneficial for multiple processes at low doses, including bone mineralization and wound healing [25], the safety profile of BA is controversial due to its toxic properties at high doses [25]. The long-term effects of intravaginal BA are unclear, and it is questionable if vaginal absorption could pose a problem. The number of adverse events in the included studies was low, temporary, and mild. However, it is possible that rare but serious side effects exist. Topical administration of BA 600 mg appears safe, but treatment regimens vary greatly depending on the type of vaginitis, and while 14 days of BA 600 mg daily in VVC patients seem efficient, a few cases of TV infections required up to 60 days of 1200 mg per day. Extended regimens of BA in BV and TV patients could thus prove more successful, but studies that assess the long-term effects and adverse effects are warranted. Given uncertainties use of BA in pregnancy and lactating woman should be avoided [74].

BA therapy has limitations. Due to its daily topical application, it is less convenient to use than oral medications. The topical application makes it less suitable for deep seated infections such as TV and will likely result in prolonged treatment duration. When it comes to availability, BA can be difficult to obtain in some countries and prices can be higher than conventional therapy. There are no studies on the safety of BA in pregnancy and during lactation and it should therefore not be used during these circumstances. Only four RCTs were included and the remaining studies had either inconsistent results, intermediate (B), or low level of evidence (C) as well as small sample sizes. Thus, heterogeneity did not allow a meta-analysis to be performed. It was especially difficult to conclude on BV and TV because of the limited data available.

In conclusion, the authors suggest considering the use of intravaginal BA 600 mg daily for 14 days as the first choice for VVC due to C. glabrata and azole-resistant VVC and as the second choice for RVVC when fluconazole has been used for a minimum of six months. Suggested dosage is BA 600 mg daily for 14 days followed by BA twice weekly with monthly clinical status, albeit that data are sparse regarding the length of the maintenance therapy. More studies are needed on this matter.

BA may be used for resistant BV infections in the same dosage as for VVC and RVVC. The authors, however, do not recommend the use of BA for acute symptomatic BV as there is a lack of evidence and other well-documented regimens. Regarding nitroimidazole-resistant TV infections, we suggest 600 mg twice daily, although there may be limited effects of a topical agent in this case and the optimal dose as well as the optimal time of duration is not known (Table 5).

Abbreviations

-

- NAC:

-

- Non-albicans Candida

-

- BA:

-

- Boric acid

-

- VVC:

-

- Vulvovaginal candidiasis

-

- BV:

-

- Bacterial vaginosis

-

- TV:

-

- Trichomonas vaginalis

-

- RVVC:

-

- Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis

-

- RBV:

-

- Recurrent bacterial vaginosis

-

- C.:

-

- Candida

-

- T.:

-

- Trichosporon

-

- S.:

-

- Saccharomyces

-

- P:

-

- Paecilomyces

-

- n:

-

- Number

-

- NA:

-

- Not available

-

- NAAT:

-

- Nuclic acid amplification tests.

Additional Points

Key Message. Rising microbial resistance to pharmacological treatments of microbial vaginitis calls for other treatment options. The old antisepticum boric acid is a well-tolerated and effective treatment alternative in mycotic vaginitis. Its promising effect on nonmycotic microbial vaginitis needs further investigation.

Conflicts of Interest

MLM has no conflicts of interest. DMLS was paid as a consultant for advisory board meeting by Novartis, AbbVie, Janssen, Sanofi, Leo Pharma, UCB and received speaker’s honoraria and/or received grants from the following companies: Abbvie, Galderma, Astellas, Novartis, UCB, Jamjoom Pharma, and Leo Pharma during the last 3 years. CDP has received grants from the European Society for Sexual Medicine and Nordic Society for Gynecology and Obstetrics and has received the speaker’s honoraria from the following companies: Astellas, Bayer and Boehringer Ingelheim during the last 3 years.

Open Research

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.