Development Process of a Holistic Assessment Questionnaire to Measure and Monitor Cancer-Related Fatigue

Abstract

Purpose: To understand the consequences of diseases and treatment such as cancer and thus the needs of patients for surveillance and care and to improve quality of life, patients should be assessed using a holistic approach. However, instruments to create such a holistic view do not exist and the development presents unique challenges. Therefore, this study presents a method for the development of a holistic assessment questionnaire using cancer-related fatigue (CRF) as a case.

Method: We started with (1) the definition of our construct of interest (CRF) on the theme level followed by (2) item selection, an iterative process of searching for validated questionnaires that together cover the full holistic construct. The construct definition on theme level (1) was too broad and was, therefore, redefined on the element level (construct > theme > element) based on interviews with relevant stakeholders. Hereafter, item selection (2) was performed on the element level based on a priority list, psychometric properties (e.g., discriminative parameter value) and consultation of experts and future users. Lastly, (3) items were reformulated.

Results: Initial CRF construct definition (1) resulted in 110 relevant validated questionnaires with over three thousand items, requiring a construct redefinition on element level. Seventy-two items from 21 validated questionnaires were included (2) in the preliminary holistic assessment questionnaire. For item reformulation (3), easy language was used to better suit the target population.

Conclusion: Tailoring care to the individual requires a holistic view. This article presents a novel method to develop a holistic assessment questionnaire, including an example for CRF, with several recommendations for cancer-specific instrument development. Although the development process of a holistic assessment questionnaire is time-consuming, more late and long-term effects of cancer are multidimensional and could benefit from a holistic approach in their assessment to enable personalised care, thereby improving quality of life and reducing societal impact.

1. Introduction

Many cancer survivors are not adequately supported to deal with the consequences of cancer and cancer treatment [1], which impacts physical, psychological, and social wellbeing of survivors [2, 3]. These problems lead to reduced quality of life [4] and work limitations, which can negatively impact income and social connectedness and come with substantial societal costs [5–8]. Rogers, McCabe and Dowling [9] indicated that survivors lack support after initial cancer treatment is completed. The needs of cancer survivors go beyond diagnosis and treatment, with people needing surveillance and care for the late and long-term effects of cancer treatment and comorbidities [10]. Their needs vary in intensity, frequency and complexity of care and the required management [11]. Therefore, care must be personalised to meet the needs of cancer survivors and reduce societal impact.

The biopsychosocial model is a helpful lens for understanding the consequences of cancer and cancer treatment [12]. This model was developed as health does not solely depend on biological factors but is also influenced by psychological and social influences, which demonstrate the need for a holistic approach. A holistic approach recognises a person as a whole and acknowledges the interdependence of biological, social, psychological and spiritual aspects [13]. To provide tailored care, Dekkers and Hertroijs [14] developed patient profiles for diabetes and joint replacement using self-reports. Wijlens et al. [15] developed a holistic patient profile for fatigue after breast cancer which investigates patient experience of CRF and its perpetuating factors (factors responsible for the persistence of fatigue) [16]. However, this is not yet operationalised into a holistic assessment questionnaire. This holistic assessment questionnaire could be used to personalise towards the needs of individual cancer survivors in order to provide tailored care as perpetuating factors are investigated. A holistic assessment questionnaire for late and long-term effects of cancer should be available to be able to personalise care to the needs of cancer survivors to reduce the impact of these effects in their daily life.

For cancer-specific instrument development, the following three steps are performed: (1) definition of construct [17–20], (2) item generation [17, 19–22] and (3) item reformulation [17–19, 21, 23–26] before pilot testing, validation and reliability is evaluated [18]. For holistic assessment questionnaires, the considered construct refers to the concept that is the objective to study, which is multidimensional and complex [17]. As a result, the development process of a holistic assessment questionnaire might differ from cancer-specific instrument development. Several holistic questionnaires have been developed [27–32]; however, the development process of these questionnaires is not described in detail [29, 30]. Rothrock, Kaiser and Cella [33] described the development of Patient-Reported Outcome (PRO) Measure that provide patients’ perspective on functioning, symptoms, wellbeing, and experiences with treatment. With regard to cancer-specific instrument development, validated questionnaires that assess (aspects of) the construct are preferably combined in the item generation step. The number of validated questionnaires that need to be included would be immense and many items would be irrelevant because of the multidimensionality and complexity of a holistic construct. Therefore, it is not possible to combine generic and disease-specific instruments to develop a holistic assessment questionnaire. It is important to have a detailed construct definition, to be able to operationalise a holistic construct into a compact holistic questionnaire. Instructions to develop this are lacking, which emphasizes the need for a method to develop holistic assessment questionnaires. This method is expected to have a thorough first step concerning the construct definition.

A holistic assessment questionnaire could be helpful for cancer-related fatigue (CRF) as it impacts quality of life [34, 35]. CRF is multidimensional and is one of the most common and debilitating symptoms experienced during and after cancer, but standards to select the treatment that is most appropriate for individual patients are lacking [36–38]. CRF is unlikely to decrease without treatment when experienced years after cancer treatment as perpetuating factors cause persistence of CRF [39]. Several types of treatments have been proven to be beneficial in reducing CRF. These treatments have different concepts and are, on average, effective in research settings but not for all patients [37]. The individual should be holistically assessed so that the right treatment can be selected because of CRF’s multidimensionality and significant emotional, physical, and social impact, which is not limited to cancer survivors themselves [1]. Therefore, the aims of this study are to present a method for the development of holistic assessment questionnaires including its challenges. This process will be illustrated by the operationalisation of a holistic patient profile into a holistic assessment of CRF questionnaire for CRF in breast cancer as a case [15].

This paper is organised as follows: the questionnaire development and process are described, illustrated with the example in CRF combining the methods and results, followed by the discussion. Within the description of questionnaire development, an introduction is given after which the three steps of questionnaire development follow.

2. Questionnaire Development

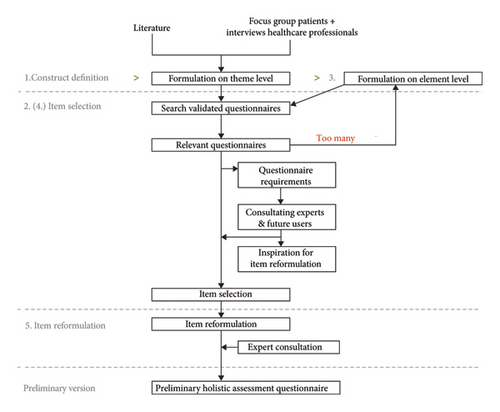

The proposed method to develop a holistic assessment questionnaire is illustrated in Figure 1, and consists of (1) construct definition on the element level, (2) item selection, and (3) item reformulation. For the construction definition (1), the construct should be defined based on thorough research, such as interviews with relevant stakeholders. Applying a holistic approach results in a broad construct definition, so we advise starting with the construct definition, composed of themes with a description on element level of each theme (construct > theme > element). Elements are the components of a theme. After the construct definition, item selection (2) is an iterative process of searching for validated questionnaires that together are able to assess the full construct and redefinition of the construct. A construct description (1) that is too broad will result in many irrelevant items on the validated questionnaires (2) because the construct of the questionnaires does not fully correspond to the construct definition. Our suggestion would be to blend, going back and forth between construct definition and validated questionnaires, and to narrow the construct description to the construct themes’ elements to be able to select items from questionnaires. A balance needs to be found between gathering as much relevant information as possible and the expected time investment of filling in the questionnaire. Item selection requires a considerable amount of work including discussion with experts and future users [21]. During item reformulation (3), the selected items are rephrased to be comprehensible for most of the target audience with the help of expert consultation. These experts should have experience in the field of the intended use of questionnaire. Each phase is described in more detail in the following and text boxes are illustrative for the example of the holistic assessment of the CRF questionnaire development process.

at 1. Construct definition indicate that inherently to a holistic approach, a construct definition is too general and should be expanded with a description on the questionnaire theme. If item selection based on construct on the theme level results in too many relevant questionnaires, construct definition should be formulated on the element level. The numbering of this Figure corresponds to the subsections of Section 2.

at 1. Construct definition indicate that inherently to a holistic approach, a construct definition is too general and should be expanded with a description on the questionnaire theme. If item selection based on construct on the theme level results in too many relevant questionnaires, construct definition should be formulated on the element level. The numbering of this Figure corresponds to the subsections of Section 2.2.1. Construct Definition—Theme Level

A construct definition is an essential first step to select what to include in the construct [40]. When the construct definition is too narrow, important elements may fail to be included, resulting in underrepresentation of the construct. Alternatively, a too broadly defined construct can result in construct-irrelevant variance as extraneous elements are included in the construct. Preferably, constructs should be grounded in a theoretical framework. The construct definition for our example is shown in Textbox 1.

2.1.1. Textbox 1: Construct Definition on the Theme Level for Holistic Assessment of the CRF Questionnaire

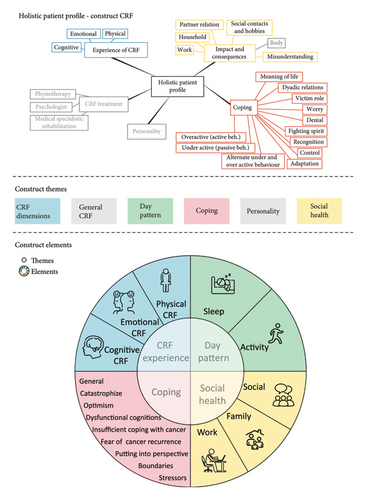

Healthcare professionals and breast cancer patients and survivors were interviewed to determine the relevant aspects for monitoring CRF holistically. This qualitative information was used to develop a holistic patient profile for CRF after breast cancer, as well as relevant literature and is described in more detail [15]. The holistic patient profile for CRF consist of the five themes: (a) experience of CRF, (b) impact and consequences, (c) coping, (d) personality, and (e) CRF treatment. A theoretical framework for CRF was not found. Therefore, themes corresponding to perpetuating factors their conceptual description or assessment method were searched for.

For an adequate construct definition of CRF, it is also important to determine which qualitative themes are all suitable for operationalisation into a questionnaire. The differences between the construct elements and holistic patient profile are explained. Dysregulation of sleep [41–46] and dysregulation of activities [41–44, 46] are perpetuating factors that were not included as a theme in the holistic patient profile but were mentioned in quotes as part of several coping styles. Therefore, sleep and activity are included in the questionnaire as elements of the theme ‘day pattern’ so that CRF (construct) > day pattern (theme) > sleep + activity (elements). Summarising, the initial themes of the operationalised questionnaire are CRF dimensions, general CRF, day pattern, coping, personality and social health. See questionnaire themes and elements in Figure 2, which also provides an overview of the construct definition process from the holistic patient profile towards the description on the element level. This corresponds to step 1, construct definition, of Figure 1.

2.2. Item Selection

It is advised to use existing validated questionnaires if possible for item selection, as development and validation of a questionnaire is a costly and time-consuming process [17, 22, 40]. Using a holistic approach, the construct is likely to consist of several themes which can be divided into elements. For the development of the holistic assessment questionnaire, it is advised to search for validated questionnaires that are able to assess the construct’s themes.

Validated questionnaires can be found via qualitative research, questionnaires used in literature and snowballing method assessing the references of the articles. Guidelines, for example, found on guideline.gov, might also be excellent sources which summarise relevant literature. In addition, one can search in scientific libraries as well as search engines. If articles discuss suitable questionnaires, they often do not include the questionnaire items, especially in languages other than English. If a questionnaire is not open access, other means should be used such as questionnaire repositories (general or disease specific) as well as contacting the authors directly.

An exhaustive list of items is a primary requisite and critical for the development of a good questionnaire [21]. Evaluation of such a list can be performed in several ways such as expert judgement, Delphi study and cognitive interviews with end users [17]. Choices need to be made to select appropriate items for the construct. A priority list, containing the questionnaire requirements, can be helpful for item selection. This priority list could relate to language, costs, scoring method, length, answer options of items, time period, target group and questionnaire use of validated questionnaires. For example, with regard to answer options, closed-ended item are easier to administer and analyse compared with open-ended items [24]. Criteria relevant for the aim of other studies could be to align with purpose of the questionnaire (diagnosing symptom, measuring symptom change and symptom inventory). The time period should align with the intended use of the instrument as well as with the temporal characteristics of the construct [47].

The item selection procedure with regard to our CRF example is illustrated in Textbox 2.

2.2.1. Textbox 2: Item Selection

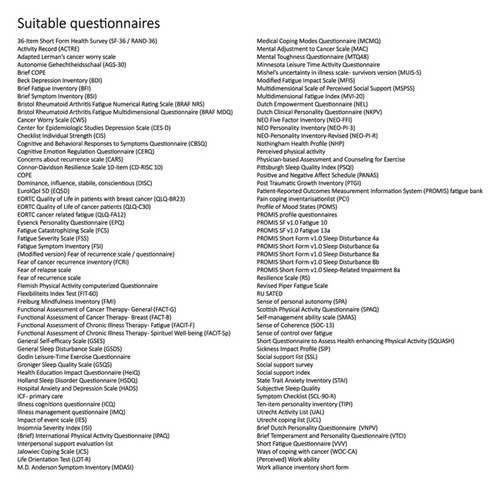

For the development of a holistic assessment of CRF questionnaire, our search aimed at finding validated questionnaires that are able to assess the questionnaires’ themes of Figure 2. Validated questionnaires followed from various sources consisting of the questionnaires mentioned by the patients and healthcare professionals who were involved in the qualitative study, as well as the questionnaires used in literature (including [48–51]), and their references (snowballing method) were consulted. The guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) were also consulted for fatigue questionnaires [52]. Repositories for instruments in general (e.g., meetinstrumentenzorg.nl, healthmeasures.net and richtlijnendatabase.nl) and disease specific (for cancer, e.g., facit.org and kankernazorgwijzer.nl) were searched. The total search resulted in 110 validated questionnaires (generic and disease specific) that are able to assess (part of) a theme or multiple themes (Figure 3).

As the 110 relevant questionnaires of Figure 3 resulted in over three-thousand questionnaire items, a priority list was necessary to assist in selecting the correct items. Table 1 shows the priority list used for the holistic assessment of the CRF questionnaire. This list was constructed by the first author and was prioritised with all authors.

| Preferably | Alternatively | Minimally | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Language | Dutch | Translation | |

| Costs | Free | Copyright | |

| Scoring | — | ||

| Target group | Breast cancer | Cancer | Other diseases |

| Length | Maximally 15 min per week for the whole questionnaire | ||

| Answer options | Likert | Multiple choice | Yes/no |

| Time period | Last week | Today | Last 4 weeks |

| Questionnaire use | Entire questionnaire | Relevant item | |

2.3. Construct Definition—Element Level

As a result of the high number of relevant questionnaires and questionnaires with items relevant for multiple themes, it will often not be feasible to include entire questionnaires. Therefore, the next step is to include items of validated questionnaires. To be able to determine which items are relevant, the construct should include description on the element level. If the construct and theme description are too broad, they have to be narrowed. The changes on the element level with regard to our example are illustrated in Textbox 3.

2.3.1. Textbox 3: Construct Definition on the Element Level (Construct > Theme > Element)

To determine the relevant items for the elements, the qualitative data about CRF conducted by Wijlens et al. [15] had to be reassessed to increase the level of detail in the overview of Figure 2. The details of questionnaire themes on the element level can be obtained from the corresponding author, in Dutch. The reassessment resulted in several changes. As the information of the questionnaire will be used to give personalised treatment advice and monitor CRF, personality as a theme is removed. Personality treatments are absent in the NCCN guidelines for fatigue and usually have minimal treatment improvement and long duration [52]. The theme “general CRF” is split over “CRF experience” and “coping” and can also be observed in Figure 2. “Body” concerns effects of CRF and breast cancer treatment on the body include loss of confidence in the body, hair loss and menopause. The NCCN guideline also does not include treatments for these individual aspects [52] and, as such, these are also left out. The individual questions of all suitable questionnaires were evaluated for relevancy to assess the elements of a theme, as described in the item selection section.

As an example of construct > theme > element, CRF is the construct with the theme day pattern and sleep as element. For the PRO measure fatigue, 13a, fatigue is divided into the experience of fatigue (frequency, duration and intensity) and the impact of fatigue on physical, mental and social activities. Therefore, sleep is not part of PRO although dysregulation of sleep [41–46] is a perpetuating factor of CRF.

2.4. Item Selection

After construct redefinition on the element level, items were selected [18]. The relevancy of items with regard to the elements of the construct can be based on the priority list, factor analysis, expert judgement and patient advocates. In the following, the selection procedure for the theme CRF experience is described in Textbox 4.

2.4.1. Textbox 4: Item Selection

For the first version of the holistic assessment questionnaire, items were selected from twenty-one validated questionnaires, summarised in Table 2. Item selection is illustrated for the theme CRF experience, as CRF can be experienced as cognitive [53, 54], emotional [53, 54] and physical [36, 46, 53–55] sensations of tiredness (CRF dimensions). Items followed from various questionnaires: EORTC QLQ-FA12 [56], MFIS [57], PROMIS [58], BRAF-MDQ [59] and EORTC QLQ-C30 [60]. The questionnaires EORTC QLQ-FA12 and MFIS [56, 57] were selected because they distinguish between the three dimensions of CRF. PROMIS [58] has a 95-item bank with fatigue questions, which were assigned to five fatigue dimensions (physical, cognitive, affective, global and motivational) by Dickson et al. [61] with a discrimination parameter value based on factor analysis to assess the best candidate item. The BRAF-MDQ [59] was used because it contains general fatigue intensity and experience questions.

| Themes | Selected questionnaires | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|

|

Bristol Rheumatoid Arthritis Fatigue Multidimensional Questionnaire | BRAF-MDQ [59] |

| European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaires Core-30 item | EORTC QLQ-C30 [60] | |

| European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaires fatigue module | EORTC QLQ-FA12 [56] | |

| Modified Fatigue Impact Scale | MFIS [57] | |

| Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Item Bank v1.0 | PROMIS Item Bank [58] | |

|

Brief International Physical Activity Questionnaire | IPAQ [62] |

| Cognitive and Behavioural Responses Questionnaire | CBRQ [63] | |

| Godin Leisure-Time exercise Physical activity Questionnaire | GSLTPAQ [64] | |

| General Sleep Disturbance Scale | GSDS [65] | |

| “RegUlarity,” “Satisfaction,” “Alertness,” “Timing,” “Efficiency,” “Duration” | RU-SATED [66] | |

|

Cognitive and Behavioural Responses Questionnaire | CBRQ [63] |

| European organization for research and treatment of cancer quality of life questionnaires fatigue module | EORTC QLQ-FA12 [56] | |

| Functional assessment of chronic illness therapy— spiritual wellbeing | FACIT-Sp [67] | |

| Modified Fatigue Impact Scale | MFIS [68] | |

| Dutch empowerment—questionnaire | NEL [69] | |

|

Bristol rheumatoid arthritis fatigue—numeric rating scale | BRAF-NRS [70] |

| Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire | CERQ [71] | |

| Functional assessment of chronic illness therapy, spiritual wellbeing | FACIT-Sp [67] | |

| Fatigue catastrophizing scale | FCS [72] | |

| Life orientation test revised | LOT-R [73] | |

| Mental adjustment to cancer scale | MAC [74] | |

| Nederlandse empowerment, Vragenlijst | NEL [69] | |

| Pain coping inventory | PCI [75] | |

| Posttraumatic growth inventory | PTGI [76] | |

| Symptom checklist-90-revised | SCL-90-R [77] | |

| Self-efficacy scale | SES [78] | |

- Note: The themes’ elements were left out because of the high number of elements.

As the experience of CRF can vary, we intended to compose an item list with relevant items for the CRF dimensions (physical, cognitive and emotional) based on the construct definition on the element level. However, emotional fatigue items appeared scarce. To avoid an imbalance between the CRF dimensions, the composed item list, including seven items per dimension, was created by the first three authors, considering the discrimination parameter values. This item list was evaluated with patient advocates to select the five most relevant questions for physical, cognitive and emotional fatigue. During consultation with patients’ advocates, one of them missed an item about irritability, which was found in the EORTC QLQ-C30 [60]. After the initial selection, the members of the Personalised cAnceR TreatmeNt and caRe (PARTNR) project were consulted for feedback. The PARTNR project aims to provide personalised intervention recommendations for breast cancer patients with CRF by developing an intelligent self-learning system. PARTNR is a collaboration between secondary and tertiary healthcare institutes and companies. The approach for the other themes, namely, “day pattern,” “social health” and “coping” was similar.

For the four included themes (CRF experience, day pattern, social health and coping), seventy-two items from twenty-one validated questionnaires were included, see Table 2. The EORTC QLQ FA12, MFSI, CBRQ, FACIT-Sp and NEL provided questions for more than one theme.

2.5. Item Reformulation

If items of validated questionnaires are selected to provide the necessary information for the holistic patient profile for a concise questionnaire, the newly composed questionnaire needs to be validated. This creates the opportunity to reformulate items to better suit the target population, and to realise similar response and time formats of the used questionnaires. Pharos, a Dutch national expertise centre contributing to reduce health inequalities, indicated that questionnaires developed for scientific research are not able to measure the outcomes in one third of the patients because of the lack of understandability [26].

For item formulation, it is important that the items are clear, brief, unambiguous, and address only one element for methodological consideration [17, 24–26]. Also, positive concepts should be phrased positively, and negatives should be avoided when possible [23, 24]. In addition, it is advised to use questions instead of statements [24, 26]. Concerning the number of items, it must be sufficient to measure the construct of interest; however, too many items can result in loss of respondent motivation [24]. Different types of scales can be used such as frequency, Likert type or multiple choice [18]. For self-report questionnaires, the reading level should generally be about A2-B1 or Grade 6 level to be understood by the majority [24]. For Grade 6 level in English, use of Lexile Analyzer is advised to adjust the language to Grade 6 level to be understandable for the majority of respondents [23]. Regarding readability, short sentences and commonly used words are important [23].

The following adjustments could be considered in the development of the holistic assessment questionnaire to better suit the target population: the language level, sentence structure, answers options, and number of questions [17, 23–26]. For sentence structure, active, brief, and clear sentences without expressions, metaphors or the like, are preferred, as well as avoiding statements. Regarding the answer options, three answer options that are placed below the question are preferred. In addition, an even number of answer options could be chosen to avoid having a neutral middle option. It is important to realise similar answer options when including items from several validated questionnaires, to ensure they are understandable for the respondents. After item reformulation, a final set of items is compiled forming the holistic assessment questionnaire. This last step is exemplified in Textbox 5.

2.5.1. Textbox 5: Item Reformulation in the Holistic Assessment of the CRF Questionnaire

The questionnaire was developed in Dutch. To check if the items are clear and at the A2-B1 level, tools of Loo van Eck [79, 80] can be used for the Dutch language. The alternative wording of modified items was discussed with all authors. One item for coping is based on the Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R) [73], which is a generic scale that measures dispositional optimism and pessimism.

- □

I agree a lot

- □

I agree a little

- □

I neither agree nor disagree

- □

I disagree a little

- □

I disagree a lot

The item is a statement instead of a question. Therefore, the item was rewritten into a question. In addition, there are five answers options whereas we preferred four to avoid the neutral middle option, which was removed. Therefore, the reformulated item is:

- □

I agree a lot

- □

I agree a little

- □

I disagree a little

- □

I disagree a lot

After this step, there was a final list of 72 items forming the first version of the holistic assessment of the CRF questionnaire developed for breast cancer survivors to use for personalised CRF treatment recommendations and monitoring of CRF in daily life.

The development process, illustrated with our example of CRF, shows that using a holistic approach in questionnaire development requires a more detailed construct description on the element level to be able to compose a compact questionnaire with relevant items (Figure 1).

Reporting guidelines (via equator-network.org such as CONSORT, STROBE, COREQ, PRISMA, etc.) were checked for but no relevant reporting guidelines corresponding to the methodology of this study were found.

3. Discussion

Tailoring care to an individual, requires a holistic overview of this individual and their context. With this article, we propose a method to develop a holistic assessment questionnaire. The development process consists of construct definition on the element level, item selection and item reformulation. Development of a holistic assessment questionnaire is time consuming, and this was exemplified by the operationalisation of the holistic patient profile for CRF into a holistic assessment questionnaire, which resulted in including items of twenty-one different validated questionnaires. This was only possible after an immense questionnaire search, composing a priority list to select the relevant items, and evaluation with experts and patient advocates. It is advised to determine the needed items on the element level instead of the theme level in contrast to the cancer-specific instruments developed method. The construct definition on the element level was based on interviews with healthcare professionals and breast cancer patients and survivors [15]. The current healthcare system consists of specialised departments, which increases the expertise on a symptom or specific disease but does not consider the patient holistically nor use the biopsychosocial model [12]. The experience and impact of CRF are also perpetuated by psychological and social influences; therefore, the holistic assessment of the CRF questionnaire contains the themes “coping” and “social health.” Future research is needed to determine if the developed holistic assessment of the CRF questionnaire based on qualitative research for breast cancer, could be extrapolated to other types of cancer. Although the development process of a holistic assessment questionnaire is time-consuming, more PROs such as late and long-term effects of cancer are multidimensional and could benefit from a holistic approach in their assessment to enable personalised care and thereby improve quality of life and reduce societal impact.

Newly developed questionnaires must be validated when adapted items or parts of questionnaires are included, resulting in the opportunity to adapt the items to better suit the target population. Validation consists of several different methods, such as face, content, construct, convergent and criterion validation [17, 20, 22, 81, 82]. Face validation assess if the questionnaire measures the intended measure via qualitative research with experts. Regarding content validity, quantitative measures are used to determine if the items of the questionnaire address all the relevant items of the construct [22, 82]. Construct validity aims to show strong correlations between the same constructs and weak correlations with different constructs whereas convergent validity determines the correlation between a scale and conceptually similar (sub)scales [22, 82]. Criterion validity evaluates the instrument compared with the golden standard [82, 83]. As a result of the holistic approach, construct or convergent validity will be unfeasible because of the number of questionnaires that need to be included which also would not resemble the construct description. This also implies that it is not possible to have used factor analysis in the development of the questionnaire. Therefore, face and content validity are the preferred next step to validate the holistic assessment questionnaire. Subsequent research depends on the purpose of the holistic assessment questionnaire (diagnosing symptom, measuring symptom change, symptom inventory).

The holistic assessment questionnaire measures a construct (in our example CRF) consisting of themes (e.g., experience of CRF) that are divided into elements (e.g., cognitive fatigue, emotional fatigue, and physical fatigue) so that construct > themes > elements. A possible disadvantage of this approach is the interpretation, as usually the score of a questionnaire represents the construct as the sum of the underlying themes. This approach implies that adding the themes would result in the construct. However, one can wonder if the sum of the themes always represents the construct. With regard to our example, three themes are about perpetuating factors while the other concerns the experience of CRF. The themes could also be considered as latent variables as they represent an underlying concept measured indirectly (e.g., social health), usually represented as subscales of a questionnaire [21]. In this case, one could score per theme. If the themes (in our example, CRF experience, day pattern, social health and coping) are considered as individual constructs, CRF should have a hierarchical higher level and could, therefore, be something abstract like a network. CRF as the questionnaire’s construct is most logical since fatigue is a tangible concept. For validation, this need to be clearly stated as construct validity is normally researched on the construct level and thus the questionnaire level. If the themes are considered separate constructs, construct validity should be performed on the subscale or theme level. This issue also could arise for other holistic assessment questionnaires developed in the future. Concerning the abovementioned, we propose to have one construct for the holistic assessment questionnaires which could consist of several themes. To validate the holistic assessment questionnaire, face validation and content validation are possible [21].

A validated questionnaire could provide questions for more than one construct theme. This also indicates that only combining generic and cancer-specific instruments to holistically assess late and long-term effects of cancer does not work as shown for CRF. Because of the holistic approach, this would result in a misalignment in the constructs of concept of existing validated questionnaires and the developed questionnaire.

Several resources were used to search for validated questionnaires that could be of use in the development process. As a result, an overview of existing questionnaires related to our construct was created. However, it is challenging to find the items and for some questionnaires, the individual items are not publicly accessible. This is a limitation since this restricted the consulted questionnaires and it could be that other relevant items were missed because of unavailability of questionnaires. However, as the number of questionnaires that were used in our example was still relatively large, we do not believe this affected the findings. Finding repositories with an overview of instruments reduced the number of unavailable questionnaires, for example, the Dutch validation of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). The article of van Poppel et al. [84] does not contain the questionnaire but it is available at meetinstrumentenzorg.nl [62]. Developed questionnaires should, therefore, be published open access to avoid this limitation for future research. It is understandable that questionnaires are not published openly as protecting intellectual property can be challenging and hinder implementation.

4. Conclusion

In this study, we proposed a method to develop a holistic assessment questionnaire to be able to personalise towards the needs of individual cancer survivor. The development of a holistic assessment questionnaire consists of a construct definition with assessing the requirements on the element level, item selection and item reformulation. We illustrated these steps using the development of a holistic assessment questionnaire for CRF after breast cancer. To develop a holistic assessment questionnaire, several adjustments with regard to cancer-specific instruments development were proposed, whereafter we presented a strong and novel method to develop holistic assessment questionnaires. This method could serve as a blueprint for the development of other holistic assessment questionnaires to tailor care and thereby improve quality of life of cancer survivors and reduce societal impact.

In the future, open access questionnaire repositories would limit the time burden of the development process of a holistic assessment questionnaire. Preferably, these repositories also contain information about the language availability, scoring procedure, intended use and target population in which the questionnaire is validated and reliable.

Ethics Statement

This is a methodological article for which no ethical approval is required.

Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

The study was conceptualised by K.W., A.W., L.B., S.S., M.V. and C.B. Data were collected, analysed, visualised and written into the first draft of the manuscript by K.W. under the supervision of A.W., M.V. and C.B. All the authors critically revised various versions of the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Queen Wilhelmina Fund (KWF) Kankerbestrijding and Dutch Research Council (NWO) Domain AES, as part of their joint strategic research programme: Technology for Oncology II. The collaboration project is cofunded by the PPP Allowance made available by Health∼Holland, Top Sector Life Sciences & Health, to stimulate public–private partnerships.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The generated datasets are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request in Dutch. During the research phase, the questionnaire is not yet publicly available.