Necrotizing Sarcoid Granulomatosis: A Disease Not to be Forgotten

Abstract

Sarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disease of unknown aetiology characterised by the appearance of noncaseifying epithelioid granulomas in the affected organs, most commonly the lungs, skin, and eyes (Iannuzzi et al. 2007). Necrotizing Sarcoid Granulomatosis (NGS) is a rare and little-known form of disease, which also presents nodular lung lesions, and it shares pathologic and clinical findings with sarcoidosis, where the presence of necrosis may lead to misdiagnosis of tuberculosis (TB), leading to a consequent delay in treatment of the underlying entity (Chong et al. 2015). This is exactly what happened with the two cases that we present here.

1. Case Presentation

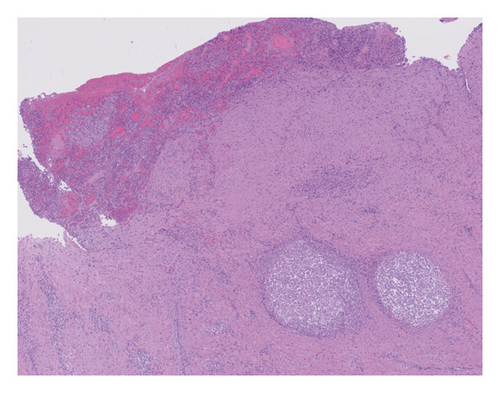

Case 1 was a 24-year-old woman who was 37 weeks pregnant, referred to our Internal Medicine unit because of a deep supraclavicular lymphadenopathy on the left side whose fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) revealed granulomas with necrosis. Case 2 was a 31-year-old male with neurological symptoms (bradypsychia, peripheral vertigo, weakness in right lower limb, instability, and sphincter incontinence), whose cerebral nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) revealed the presence of meningeal uptake; chest tomography scan (CT) showed mediastinal nodules and bilateral bronchoalveolar infiltrates; and the open lung biopsy showed sarcoid-like granulomas with extensive necrosis. Both patients received initially standard antituberculous treatment, but due to lack of response, the possibility of a necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis raised up. After the start of treatment with glucocorticoids, the evolution was favourable in both cases. Table 1 provides more details of these cases.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex and age | 24-year-old female. 37 weeks pregnant | 31-year-old male |

| Family history | Father diagnosed with discoid lupus | Brother diagnosed with sarcoidosis (pulmonary and cutaneous involvement) |

| Presentation | Left supraclavicular lymphadenopathy | Peripheral vertigo, weakness in right lower limb, instability, and sphincter incontinence |

| Physical examination | Approx. 4 × 4 cm supraclavicular tumour attached to deep planes | Bradipsychia. Right horizontal nystagmus. Paresis 4+/5 left upper limb and lower limbs. Left extensor cutaneous plantar reflex. Unstable romberg |

| Laboratory |

|

|

| Imaging tests |

|

|

| Anatomical pathology |

|

Open lung biopsy: necrotizing granulomatous infiltrates. PCR mycobacterium tuberculosis: negative |

2. Discussion

Necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis was first described in 1973 by Liebow, who noted the histological presence of confluent epithelioid granulomas with small central necrosis foci or more extensive necrosis, as well as vasculitis [1]. Liebow diferentiated this granulomatous disease from other forms of noninfectious pulmonary angiitis and granulomatosis: Wegener’s granulomatosis, Churg–Strauss syndrome, bronchocentric granulomatosis, and lymphomatoid granulomatosis. Actually most authors consider the entity as a form of sarcoidosis more than a distinct entity, differing in the fact that there is more intense necrosis and vasculitis [2].

Clinically, very few differences have been described between the two variants: classical and necrotizing, with pulmonary involvement predominating in both. Table 2 provides more detail on differences between them. In case 1, the clinical manifestation was a supraclavicular lymphadenopathy; peripheral lymphadenopathy appears in 40% of sarcoidosis patients. It should be noted that the presence of intrathoracic lymphadenopathies is more frequent in the classic form (85%) than in the necrotizing form (33%). In case 2, the predominant manifestation was central nervous system (CNS) involvement, which appears in 5.78% of NGS patients [3] and in the same proportion in patients with the classic form [4].

| Nodular sarcoidosis | Necrotizing variant | |

|---|---|---|

| Epidemiology |

|

|

| Histology | Nonnecrotizing epithelioid granulomas |

|

| Clinical presentation |

|

|

| Involved organs | ||

| >>SACE elevation | 17% | 4% |

| >>Eye involvement | 14% | 12% |

| >>Skin involvement | 10% | 2% |

| >>Lymphadenopathy | 9% | 0.5% |

| >>Liver involvement | 9% | 1% |

| >>Erithema nodosum | 3% | 1% |

| >>Sjögren or sicca syndrome | 1% | 3% |

| >>CNS involvement | 2% | 7% |

| >>Neuropathy | 0% | 2% |

| >>Splenic involvement | 2% | 1% |

| >>Lacrimal gland involvement | 1% | 2% |

| Diagnosis |

|

Tissue obtained by surgical procedures (98%) |

- SACE: serum angiotensin converting enzyme; CNS: central nervous system.

In respect of tuberculosis, the most frequent clinical presentation is also pulmonary involvement. The most frequent extrapulmonary form is lymph node tuberculosis, which is responsible for 43% of peripheral lymphadenopathies in the developed world [6]; CNS involvement is rarer (5.5%); due to this, it requires haematogenous dissemination either from a distal focus or during disseminated TB [7].

Correct diagnosis is vital because of the different treatments for the pathologies. Necrotizing sarcoidosis has a good response to corticoids, becoming benign [2, 5], and exceptionally severe neural involvement leading to death has been reported [3]. In contrast, tuberculosis disease requires TB treatment over a period of time that depends on the area affected [7].

Given the low effectiveness of cultures from most extrapulmonary locations for studying extrapulmonary tuberculosis, biopsy may be required for diagnosis. Visualising granulomas with caseification necrosis in biopsy samples, together with a compatible medical history, is practically diagnostic. Even so, samples should always be processed for microbiological study (staining, PCR, and culturing). A lack of microbiological isolation in the samples should therefore lead us to suspect a different granulomatous disease, such as necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis [8].

Similarly, in patients suspected of having an active tuberculosis infection (based on clinical radiological findings), it is recommended to initiate the antituberculous regimen prior to microbiological isolation and evaluate the response after 2-3 weeks, while the microbiological results are being prepared. If there are no clinical or radiological changes and the microbiological study is negative, steroid therapy can be started [8].

In the two cases presented here, TB treatment was initiated. Given the absence of a favourable response, it was performed a biopsy that led to the diagnosis, allowing corticoid treatment to be initiated. In both patients, good disease control was achieved with low doses of corticoids, combined with methotrexate in case 2, permitting rapid reduction in prednisone doses.

3. Conclusion

Necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis should be considered within the differential diagnosis of granulomatous diseases (Table 3), and knowledge of this variant is essential in order not to rule out sarcoidosis due to the presence of necrosis. The extended duration of the disease, its glucocorticoid response, negative cultures, and lack of response to TB treatment make it less likely for the aetiology to be infectious [8].

| GPA | EGPA | TB | NTM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epydemiology |

|

|

|

Environmental contaminants in soil and water, having been isolated from the domestic water distribution network, hot tubs, swimming pools, and workplaces |

| Histology | Granulomatous inflammation, vasculitis, and necrosis |

|

Granulomas caseating which contain epithelioid macrophages, Langhans giant cells, and lymphocytes | Granulomatous inflammation |

| Clinical presentation |

|

|

|

|

| Laboratory tests |

|

|

CRP elevated. Leukocytosis Hyponatremia, may be associated with the SIADH | Elevated acute phase reactants |

| Diagnosis | Biopsy of a site of suspected active disease | Surgical lung biopsy | Radiographic imaging (radiography and TC) and microbiologic testing (sputum AFB smear, mycobacterial culture, and molecular tests) |

|

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.