Strongyloidiasis in Africa: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on Prevalence, Diagnostic Methods, and Study Settings

Abstract

Background. Strongyloidiasis is an intestinal parasitic infection mainly caused by Strongyloides stercoralis. Although it is a predominant parasite in tropics and subtropics where sanitation and hygiene are poorly practiced, the true prevalence of strongyloidiasis is not known due to low-sensitivity diagnostic methods. Objective. This systematic review and meta-analysis is aimed at determining the pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis in African countries, stratified by diagnostic methods, study settings, and patients. Methods. Cross-sectional studies on strongyloidiasis published in African countries from the year 2008 up to 2018 in PubMed and Google Scholar databases and which reported at least one Strongyloides spp. infection were included. Identification and screening of eligible articles were also done. Articles whose focus was on strongyloidiasis in animals, soil, and foreigners infected by Strongyloides spp. in Africa were excluded. The random effects model was used to calculate the pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis across African countries as well as by diagnostic methods and study settings. The heterogeneity between studies was also computed. Result. A total of 82 studies were included. The overall pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis was 2.7%. By individual techniques, the pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis was 0.4%, 1.0%, 3.4%, 9.3%, 9.6%, and 19.4% by the respective direct saline microscopy, Kato-Katz, formol ether concentration, polymerase chain reaction, Baermann concentration, and culture diagnostic techniques. The prevalence rates of strongyloidiasis among rural community, school, and health institution studies were 6.8%, 6.4%, and 0.9%, respectively. The variation on the effect size comparing African countries, diagnostic methods, study settings, and patients was significant (P ≤ 0.001). Conclusions. This review shows that strongyloidiasis is overlooked and its prevalence is estimated to be low in Africa due to the use of diagnostic methods with low sensitivity. Therefore, there is a need for using a combination of appropriate diagnostic methods to approach the actual strongyloidiasis rates in Africa.

1. Introduction

Strongyloides stercoralis is one of the soil-transmitted helminths (STHs) that cause strongyloidiasis. There are more than 60 species in the genus which parasitize the duodenum of the small intestine of humans and domestic mammals [1]. Only two species S. stercoralis and S. fuelleborni are known to infect human beings. Strongyloides stercoralis is distributed in tropical and subtropical areas whereas S. fuelleborni infection is found in Papua New Guinea and sporadically in Africa [2].

The true prevalence of strongyloidiasis is underestimated and underreported due to the use of diagnostic methods with poor sensitivity [3]. An estimated 370 million strongyloidiasis occur globally [4], being 90% of them in sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, Latin America, Oceanian countries, and the Caribbean islands and is related to poor sanitation and hygiene practices [5]. Studies showed that high numbers of strongyloidiasis occur among children [6] and immunocompromised individuals [7]. Several factors including malnutrition, autoimmune diseases, and taking corticosteroid drugs that impaired the immune system may contribute for the high prevalence of strongyloidiasis [8].

In developing countries, the risk of acquiring strongyloidiasis is higher in rural dwellers, having low socioeconomic status [9] and poor sanitation infrastructures [10]. Infection ranges from asymptomatic to life-threatening clinical manifestations depending on the level of immunity [11]. The infection appears when the filariform larva enters the human body through skin penetration and crosses the lung during larva migration, and the adult reaches the small intestine. The larvae may cause skin rashes, dry cough, and recurrent sore throat whereas the adult stage of the parasite may also cause abdominal pain, loss of appetite, diarrhea, blood in stool, epigastric pain, and bloating, but most frequently, the infection is asymptomatic [12].

Strongyloidiasis is detected by microscopic-based diagnostic methods like direct saline microscopy (DSM) [3], formol ether concentration technique (FECT) [13], Baermann concentration technique (BCT) [14], agar plate technique (APT) [15], and immunological [16] and molecular-based techniques [17].

The Baermann concentration technique may increase the detection rate of strongyloidiasis by 3.6-4 times compared to the FECT or DSM technique [18]. In the same way, serological assays [16] and real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) techniques have shown to be more sensitive diagnostic tools for S. stercoralis detection [17].

The sensitivity of BCT, APT, RT-PCR, and ELISA is good, but not enough. Moreover, they have limitations for application in countries of poor resource in Africa. Because of that, a combination of techniques is the recommended approach for diagnosing the infection. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis is aimed at providing an overview of the prevalence of strongyloidiasis across African countries, stratified by diagnostic methods, study settings, and patients.

2. Materials and Methods

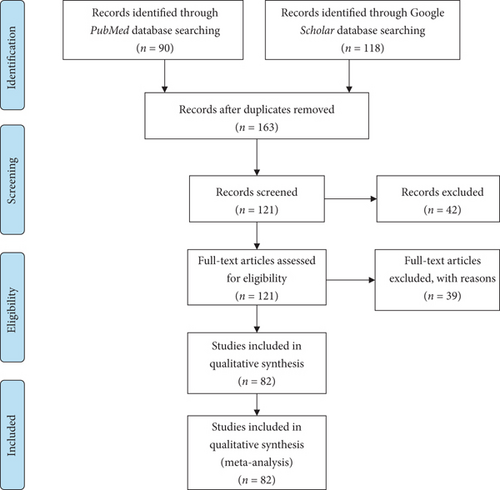

A search on the databases PubMed and Google Scholar was done for studies written in English from the year 2008 up to 2018. Keywords used in the search were “Strongyloidiasis,” “Strongyloides,” “Strongyloides stercoralis,” and “Soil-transmitted helminths” in each African country. The search for electronic data of studies was conducted between July 2019 and August 2019. Identification, screening, and checking the eligibility and the inclusion of the relevant studies were done following the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) (Figure 1). The articles extracted from the two databases were first screened to remove duplication. Furthermore, the articles were screened by reading their abstracts and the full articles and then the articles which did not investigate the prevalence of strongyloidiasis.

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

All cross-sectional studies from 2008 to 2018 conducted in African countries among patients or any participants in Africa and diagnosed by DSM, KK, FECT, BCT, culture, PCR, or a combination of these diagnostic techniques and obtained at least one positive for Strongyloides spp. were included. Including only PubMed and Google Scholar databases was the limitation.

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

All studies on strongyloidiasis in animals, soil, foreigners in African countries or imported cases, nondefined study population, sample sources other than stool, analysis of S. stercoralis-positive cases only, method comparisons, case studies, cohort studies, duplications, articles conducted before the year 2008, and review articles done in African countries were excluded. The suitability of all studies according to the defined criteria was judged independently by two different authors. Any differences in judgment were resolved by discussion among the authors.

For each selected paper, the following information was recorded: number of infected individuals, number of examined individuals, country name, types of diagnostic method used, study setting where date were collected, and types of disease recorded in health institution. The pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis in African countries as well as by each diagnostic method, study settings, and among patients was computed using a random effects model.

The meta-analysis was performed using comprehensive meta-analysis 2.2 software (Biostat Inc., Englewood, NJ, USA). The pooled overall prevalence of strongyloidiasis at 95% confidence interval (CI) in African countries was calculated using a random effects model. The pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis by diagnostic methods, study settings, and patients was calculated in the subgroup analysis. The forest plot was reported, and separate meta-analyses were performed to evaluate the effect of diagnostic methods, study settings, and patients in health institutions with strongyloidiasis. Heterogeneity (the difference between studies) by country, diagnostic methods, study settings, and among patients was assessed using Cochran (Q) value, P value, and I2 and visual inspection of the forest plot. The level of significance for all tests was P ≤ 0.001. Publication bias that occurs in published studies was checked by considering effect size symmetry on funnel plot (a scatter plot of estimates). Absence of bias is presented by shape like a funnel.

3. Result

A total of 208 (90 from PubMed and 118 from Google Scholar databases) studies were identified. One hundred sixty-three studies were screened and recorded after duplications removed. One hundred twenty-one studies were found to be eligible after full-text assessment, and finally, 82 studies were included in qualitative analysis (Figure 1).

3.1. Prevalence of Strongyloidiasis

Twenty African countries having strongyloidiasis research reports and fulfilling the inclusion criteria were involved with the total participants being 96,069 (Table 1).

| Authors’ information and reference | Diagnostic methods | Study settings | S. stercoralis Pos (n, %) | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dacal et al., 2018, Angola [19] | PCR | School | 75 (21.4) | 351 |

| Bocanegra et al., 2015, Angola [20] | FECT | School | 1 (0.07) | 1425 |

| de Alegrıa et al., 2017, Angola [21] | BCT, FECT | School | 28 (12.2) | 230 |

| Karou et al., 2011, Burkina Faso [22] | DSM | H/institution | 6 (0.05) | 11,728 |

| Bopda et al., 2016, Cameroon [23] | KK | H/institution | 7 (2.1) | 334 |

| Nsagha et al., 2016, Cameroon [11] | FECT | H/institution | 2 (0.7) | 300 |

| Kuete et al., 2015, Cameroon [24] | FECT | H/institution | 4 (0.9) | 428 |

| Becker et al., 2015, Côte d’Ivoire [25] | BCT, culture, PCR | Community | 56 (21.9) | 256 |

| Glinz et al., 2010, Côte d’Ivoire [26] | BCT, culture | School | 68 (27.1) | 251 |

| Rayan et al., 2011, Egypt [27] | BCT, FECT, culture, PCR | H/institution | 18 (15.7) | 115 |

| Roka et al., 2013, Equatorial Guinea [28] | FECT | H/institution | 28 (10.3) | 273 |

| Roka et al., 2012, Equatorial Guinea [29] | FECT | H/institution | 23 (8.8) | 260 |

| Amor et al., 2016, Ethiopia [6] | BCT, FECT, PCR | School | 82 (20.7) | 396 |

| Abdia et al., 2017, Ethiopia [30] | FECT | School | 3 (0.7) | 408 |

| Ramos et al., 2014, Ethiopia [31] | DSM | H/institution | 92 (0.3) | 32191 |

| Zeynudin et al., 2013, Ethiopia [32] | FECT | H/institution | 6 (6.6) | 91 |

| Assefa et al., 2009, Ethiopia [33] | FECT | H/institution | 28 (7.4) | 378 |

| Wegayehu et al., 2013, Ethiopia [34] | FECT | Community | 51 (5.9) | 858 |

| Huruy et al., 2011, Ethiopia [35] | DSM | H/institution | 12 (3.1) | 384 |

| Gedle et al., 2015, Ethiopia [36] | FECT | H/institution | 5 (1.6) | 305 |

| Abera et al., 2013, Ethiopia [37] | FECT | School | 27 (3.4) | 788 |

| Derso et al., 2016, Ethiopia [38] | DSM | H/institution | 6 (1.6) | 384 |

| Fekadu et al., 2013, Ethiopia [39] | FECT | H/institution | 36 (10.5) | 343 |

| Abate et al., 2013, Ethiopia [40] | FECT | H/institution | 8 (2.0) | 410 |

| Alemu et al., 2017, Ethiopia [41] | FECT | H/institution | 4 (1.8) | 220 |

| Teklemariam et al., 2013, Ethiopia [42] | FECT | H/institution | 15 (4.0) | 371 |

| Legesse et al., 2010, Ethiopia [43] | FECT | School | 1 (0.3) | 381 |

| Hailu et al., 2015, Ethiopia [44] | FECT | H/institution | 5 (0.05) | 100 |

| Nyantekyi et al., 2010, Ethiopia [45] | FECT | Community | 38 (13.2) | 288 |

| Chala, 2013, Ethiopia [46] | DSM | H/institution | 73 (1.2) | 6342 |

| M’bondoukwé et al., 2018, Gabon [47] | DSM | Community | 10 (3.7) | 270 |

| Janssen et al., 2015, Gabon [48] | Culture | H/institution | 10 (4.0) | 252 |

| M’bondoukwé et al., 2016, Gabon [49] | DSM | H/institution | 1 (1.0) | 101 |

| Adu-Gyasi et al., 2018, Ghana [50] | FECT | Community | 14 (0.9) | 1569 |

| Nkrumah et al., 2011, Ghana [51] | DSM | Hospital | 6 (0.6) | 1080 |

| Forson et al., 2017, Ghana [52] | FECT | School | 1 (0.3) | 300 |

| Yatich et al., 2009, Ghana [53] | BCT | H/institution | 29 (3.9) | 746 |

| Sam et al., 2018, Ghana [54] | FECT | School | 20 (5.1) | 394 |

| Cunningham et al., 2018, Ghana [55] | PCR | Community | 5 (1.1) | 448 |

| Kagira et al., 2011, Kenya [56] | DSM | H/institution | 3 (9.7) | 31 |

| Walson et al., 2010, Kenya [57] | FECT | Community | 20 (1.3) | 1541 |

| Arndt et al., 2013, Kenya [58] | FECT | Community | 5 (3.3) | 153 |

| Meurs et al., 2017, Mozambique [59] | FECT, BCT, PCR | Community | 147 (48.5) | 303 |

| Cerveja et al., 2017, Mozambique [60] | DSM | H/institution | 5 (1.3) | 371 |

| Chukwuma et al., 2009, Nigeria [61] | FECT | School | 13 (5.9) | 220 |

| Uhuo et al., 2011, Nigeria [62] | FECT | School | 4 (0.5) | 800 |

| Wosu and Onyeabor, 2014, Nigeria [63] | FECT | School | 11 (3.6) | 304 |

| Simon-oke et al., 2014, Nigeria [64] | DSM | School | 23 (12.8) | 180 |

| Adekolujo et al., 2015, Nigeria [65] | FECT | H/institution | 4 (0.6) | 717 |

| Olusegun et al., 2011, Nigeria [66] | DSM | School | 2 (0.7) | 304 |

| Abaver et al., 2011, Nigeria [67] | FECT | H/institution | 3 (2.5) | 119 |

| Ivoke et al., 2017, Nigeria [68] | FECT | H/institution | 8 (1.0) | 797 |

| Ojurongbe et al., 2018, Nigeria [69] | FECT | H/institution | 2 (1.0) | 200 |

| Emeka, 2013, Nigeria [70] | FECT | School | 28 (11.0) | 255 |

| Esiet and Edet, 2017, Nigeria [71] | FECT | School | 46 (4.4) | 1055 |

| Manir et al., 2017, Nigeria [72] | FECT | School | 10 (4.0) | 252 |

| Onyido et al., 2016, Nigeria [73] | FECT | School | 1 (0.8) | 120 |

| Abah and Arene, 2015, Nigeria [74] | FECT | School | 273 (7.1) | 3826 |

| Damen et al., 2010, Nigeria [75] | FECT | School | 34 (6.8) | 500 |

| Akinbo et al., 2010, Nigeria [76] | FECT | H/institution | 23 (1.2) | 2000 |

| Ojurongbe et al., 2014, Nigeria [77] | FECT | School | 6 (3.7) | 162 |

| Amoo et al., 2018, Nigeria [78] | FECT | H/institution | 10 (4.3) | 231 |

| Alli et al., 2011, Nigeria [79] | FECT | H/institution | 4 (1.1) | 350 |

| Eke et al., 2015, Nigeria [80] | FECT | School | 63 (13.1) | 480 |

| Auta et al., 2013, Nigeria [81] | FECT | School | 12 (4.2) | 283 |

| Aniwada et al., 2016, Nigeria [82] | FECT | School | 10 (1.2) | 859 |

| Umar and Bassey et al., 2010, Nigeria [83] | Culture | School | 104 (37.1) | 280 |

| Tuyizere et al., 2018, Rwanda [84] | Culture | Community | 94 (17.4) | 539 |

| Ferreira et al., 2015, Sao Tome and Principe [85] | FECT | Community | 11 (2.5) | 444 |

| Sow et al., 2017, Senegal [86] | PCR | H/institution | 6 (6.1) | 98 |

| Babiker et al., 2009, Sudan [87] | FECT | H/institution | 2 (0.1) | 1500 |

| Mohamed et al., 2018, Sudan [88] | DSM | H/institution | 1 (0.2) | 600 |

| Knopp et al., 2014, Tanzania [89] | BCT, PCR | Community | 83 (7.4) | 1128 |

| Salim et al., 2014, Tanzania [90] | BCT | Community | 71 (6.9) | 1033 |

| Sikalengo et al., 2018, Tanzania [91] | BCT | H/institution | 89 (13.3) | 668 |

| Mhimbira et al., 2017, Tanzania [92] | BCT, FECT | Community | 161 (16.6) | 972 |

| Barda et al., 2017, Tanzania [93] | BCT, culture | School | 36 (7.1) | 509 |

| Oboth et al., 2019, Uganda [94] | KK | Refuge | 1 (0.2) | 476 |

| Stothard et al., 2008, Uganda [95] | BCT | Community | 4 (1.3) | 301 |

| Hillier et al., 2008, Uganda [96] | BCT | Community | 256 (12.4) | 2059 |

| Kelly et al., 2009, Zambia [97] | DSM | Community | 14 (0.5) | 2981 |

| Knopp et al., 2008, Zanzibar [98] | BCT, culture | Community | 7 (2.2) | 319 |

| Total | 2614 (2.7) | 96,069 |

- ∗BCT = Baermann concentration technique; DSM = direct saline microscopy; FECT = formol ether concentration technique; H/institution = health institution; KK = Kato-Katz; PCR = polymerase chain reaction.

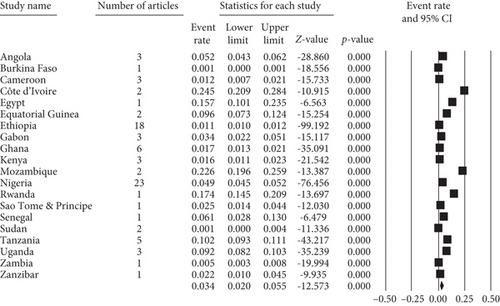

Among the 82 studies in Africa, the prevalence of strongyloidiasis ranged from 0.1% in a study conducted in Sudan [87] to 27.1% in Côte d’Ivoire [26] (Table 1). All studies in Côte d’Ivoire used a combination of two or three diagnostic techniques including PCR, BCT, and culture techniques. One of the two studies from Mozambique also used combination of FECT, BCT, and PCR reporting a prevalence rate of 48.51% [59]. The prevalence rate 17.4% in Rwanda was reported using agar plate culture among community dwellers [84]. The fourth highest prevalence 10.21% (92-96%) of strongyloidiasis was from Tanzania. All the five studies [89–93] conducted in Tanzania used BCT as diagnostic method, and three of which studies used PCR [90], FECT [93], or culture [94] (Table 1).

In Ethiopia, a relatively high number of participants 44,638 (45.1%) were included (Table 1) and the total pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis was 1.1% (1.0-1.2) (Figure 2). Most of the studies (13/18; 72.2%) used FECT, whereas four studies (22.2%) used DSM as a means of diagnosis. The majority of the studies (12/18: 66.7%) were conducted among patients visiting the health institutions for different ailments (Table 1).

In Nigeria, a total of 14,294 (14.8%) study participants were involved in 23 (27.7%) studies (Table 1). The pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis in Nigeria was 4.9% (4.5-5.2%) (Figure 2). Nineteen (82.6%) and three (13.0%) of the studies used FECT and DSM diagnosis in Nigeria, respectively. Only one study used culture diagnostic method. In addition, 15 (65.2%) and eight (34.8%) studies were conducted among school-age children and patients, respectively (Table 1).

Low pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis was reported from studies conducted in Sudan (0.14%) [87], Zambia (0.5%) [97], and Burkina Faso (0.5%) [22]. Among studies conducted in Sudan, one study conducted using DSM [88] and the other by FECT [87] had low sensitivity to strongyloidiasis detection. The studies conducted in Burkina Faso and Zambia used DSM as a diagnostic method (Table 1).

The forest plots (Figure 2) indicated the pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis among 82 studies in Africa which was 3.4% (95% CI: 2.0-5.5%) using random effects model. The highest pooled prevalence 22.6% of strongyloidiasis was recorded in Côte d’Ivoire followed by Mozambique 22.6% (19.6-25.9%), Rwanda 17.4% (14.5-20.9%), and Egypt 15.7% (10.1-23.4%) (Figure 2). The heterogeneity of studies across African countries was high (Q = 2782.625, I2 = 99.317%, P ≤ 0.001) (Figure 2).

3.2. Diagnostic Methods of Strongyloidiasis

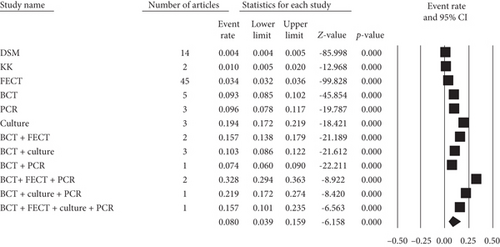

Regarding the diagnostic methods of S. stercoralis, most studies (69, 84.15%) used DM, KK, or FECT. Most of the studies (43, 52.4%) used FECT for diagnosing the infection in Africa (Figure 3). Among studies using single diagnostic methods, high pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis was recorded 19.4% in stool culture followed by 9.6% in PCR and 9.3% in BCT detection methods (Figure 3). The highest pooled prevalence rate 32.8% of strongyloidiasis was obtained by using a combination of BCT, FECT, and PCR diagnostic methods (Figure 3). The low prevalence rates of strongyloidiasis 3.4%, 0.4%, and 1.0% were also obtained using FECT, KK, and DSM diagnostic methods, respectively (Figure 3).

Forest plot (Figure 3) indicated that the pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis in Africa across different diagnostic methods was 8.0% (95% CI: 3.9-15.9%) using random effects model. Heterogeneity of studies through different diagnostic approaches was high (Q = 3497.655, I2 = 99.696%, P ≤ 0.001) (Figure 3).

3.3. Strongyloidiasis by Study Settings

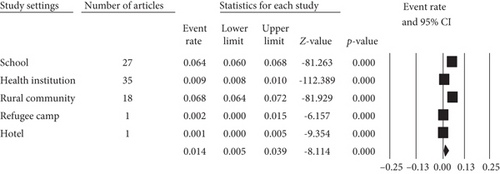

Among the total studies, 35 (42.68%) studies were conducted in health institutions followed by 27 (32.93%) in schools and 18 (21.95%) in rural communities (Figure 4).

The forest plot (Figure 4) shows the pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis across different study settings in Africa using random effects model which was 1.4% (95% CI: 0.5-3.9%). Heterogeneity of studies among the study sites in the African countries was high (Q = 1856.455, I2 = 9.785%, P ≤ 0.001) (Figure 4).

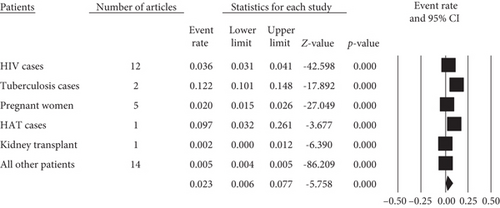

3.4. Strongyloidiasis In Health Institutions

Pooled prevalence rates of 12.2%, 9.7%, and 3.6% of strongyloidiasis were obtained with the respective tuberculosis (TB), human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) cases (Figure 5).

Forest plot (Figure 5) indicates 2.3% (95% CI: 0.6-7.7%) pooled prevalence of strongyloidiasis among patients across health institutions in Africa using random effects model. Heterogeneity of studies between patients in the African countries was high (Q = 83.334, I2 = 99.440%, P ≤ 0.001) (Figure 5).

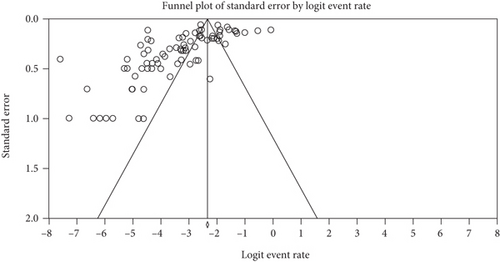

The funnel plot shows that studies were distributed symmetrically about the combined effect size that showed the absence of publication bias in this review (Figure 6).

4. Discussion

The prevalence of strongyloidiasis in Africa is difficult to estimate due to inadequacy of studies and absence of very high-sensitive diagnostic methods. In this review, authors clearly demonstrated that a study conducted with DSM, FECT, and KK methods provided low strongyloidiasis prevalence report in the African continent. This finding is supported by the most widely used diagnostic methods to helminthic infections including DSM, FECT, and KK which most likely fail to detect strongyloidiasis [18]. The justification for the low prevalence rates of strongyloidiasis in African in the current review might be due to the use of traditional methods (FECT, KK, and DSM), very small amount of stool sample used, and one-time stool sample collection which may give false-negative results. Moreover, single stool examination might also compromise the true prevalence of strongyloidiasis detection. For instance, single stool examination using DSM can detect the strongyloidiasis larvae in only 30% of the cases [99]. Furthermore, the intermittent excretion nature of S. stercoralis and chronic low-intensity infections which lead to low larval load within the stool may also affect the true prevalence [7]. Generally, most African countries use low-sensitivity diagnostic methods for strongyloidiasis detection since there is a lack of awareness and more sensitive diagnostic methods are costly and difficult to adopt in most African health institutions. As a result, they stick to using FECT and DSM with their limitations [18].

In this review, stool culture, BCT, and PCR are more sensitive methods for the diagnosis of strongyloidiasis. This finding is supported by other previous studies [15, 100]. A combination of two or three of the culture, BCT, and PCR provided better detection rate of strongyloidiasis in stool in the current review. This result agrees with a previous report [6], and better detection of strongyloidiasis was obtained using combination of BCT and other methods [101]. Nevertheless, it should be borne in mind that the sensitivity of such tests is not perfect, especially when it is performed on a single fecal specimen, diarrheic stool, and a very small amount of stool sample. All these might lead to underdiagnosis and underestimation of the true prevalence of strongyloidiasis. Therefore, there is a need to define a standard protocol in terms of diagnostic methods, the amount and consistency of stool specimens, and the frequency of examination of stool specimens for better assessment of strongyloidiasis. Such priority recommendations and elaboration of mapping guidelines should be done by the World Health Organization for strongyloidiasis like the other soil-transmitted helminthic infections and included in the neglected tropical disease (NTD) group.

The prevalence of strongyloidiasis among community dwellers of Africa in the current review was relatively high (6.69%). This is consistent with an earlier report [7]. This high prevalence of strongyloidiasis in a rural community might be due to low sanitation and hygiene practice, limited knowledge on the transmission of Strongyloides infection, and absence of adequate water for sanitation and hygiene in the rural communities of African countries [102, 103].

The prevalence of strongyloidiasis among school children was 6.4% (6.0-6.8%) in this review. A considerable similar report among school-age children is also found in a systematic review conducted in Ethiopia [104]. This might be justified firstly by the fact that African children are living in unhygienic environment with poor sanitation practices where most children play with contaminated soil and walk barefoot that increases the probability of the entrance of the filariform larvae in the body [105]. Secondly, most African children are malnourished [106] and this is evidenced by a high prevalence of strongyloidiasis among malnourished children [107]. Thirdly, a high infection rate of strongyloidiasis was seen in immunocompromised children [108].

In this review, the distribution of strongyloidiasis among patients was 2.3% (0.6-7.7%). This result is consistent with 5.1% prevalence among HIV patients in the previous report [7] but lower than 23% among Bolivian patients [108]. The difference might be due to diagnostic method difference and serological test used in addition to coproparasitological test in a study conducted in Bolivia.

In the current review, heterogeneity of studies was high and there was no publication bias. The current heterogeneity finding is consistent, but the publication bias report disagrees with a previous report [109]. The absence of publication bias might be justified as combined effect size in the current studies is distributed symmetrically using funnel plot.

Unlike other soil-transmitted helminth infections, much attention is not given to Strongyloidiasis by the policymakers although the global burden is probably much higher than previously estimated. We encourage researchers to work on standardizing diagnostic protocols of strongyloidiasis and also policymakers to include strongyloidiasis in the soil-transmitted helminth package.

4.1. Limitation of This Review

The use of only PubMed and Google Scholar databases as a source of articles was the limitation of this review.

5. Conclusions

This review shows that strongyloidiasis prevalence is overlooked and its prevalence is low in Africa due to the use of low-sensitivity diagnostic methods and lack of correct diagnostic approach. A combination of microscopic and PCR method gives good detection rate of strongyloidiasis. Therefore, there is a need for using a combination of microscopic and molecular-based diagnostic methods to determine the true prevalence in Africa. Further research is also needed to break the transmission cycle and reduce the impacts of strongyloidiasis in the African population.

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declare(s) that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contributions

All the authors acknowledged their active participation during gathering and screening of articles and critically reviewing this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Open Research

Data Availability

The data can be requested from Bahir Dar University (https://bdu.edu.et/node/74).