Essential Oils from Clausena Species in China: Santalene Sesquiterpenes Resource and Toxicity against Liposcelis bostrychophila

Abstract

To develop natural product resources from the Clausena genus (Rutaceae), the essential oils (EOs) from four Clausena plants (Clausena excavata, C. lansium, C. emarginata, and C. dunniana) were analyzed by GC-MS. Their lethal (contact toxicity) and sublethal effects (repellency) against Liposcelis bostrychophila (LB) adults were also evaluated. Santalene sesquiterpene was the precursor substance of santalol, a valuable perfumery. It was found that plenty of α-santalol (31.7%) and α-santalane (19.5%) contained in C. lansium from Guangxi Province and α-santalene (1.5%) existed in C. emarginata. Contact toxicity of the four EOs was observed, especially C. dunniana (LD50 = 37.26 µg/cm2). Santalol (LD50 = 30.26 µg/cm2) and estragole (LD50 = 30.22 µg/cm2) were the two most toxic compounds. In repellency assays, C. excavate, C. lansium, and C. emarginata exhibited repellent effect at the dose of 63.17 nL/cm2 2 h after exposure (percentage repellencies were 100%, 98%, and 96%, respectively). Four Clausena EOs and santalol had an excellent potential for application in the management of LB. Clausena plants could be further developed to find more resources of natural products.

1. Introduction

Currently, about 30 species of the genus Clausena (family Rutaceae) have been identified and are widely distributed over tropical and subtropical areas. In China, there are about 10 species grown widely in southern provinces. Some of these species have been served as a folk medicine [1]. It has been reported that secondary metabolites from the leaves, fruits, seeds, and roots of these plants result in a variety of biological activities such as antioxidant, hepatoprotective, hypoglycemic, antimicrobial, and herbicidal activities [1–4]. The plants from the genus Clausena are abundant in natural resource and possess many important sources of phytochemicals, particularly alkaloids, coumarins, limonoids, and essential oils (EOs) [1, 3]. Some EOs have pleasant odor [5–9] and have been reported to have potential for using as effective insecticides [5, 10].

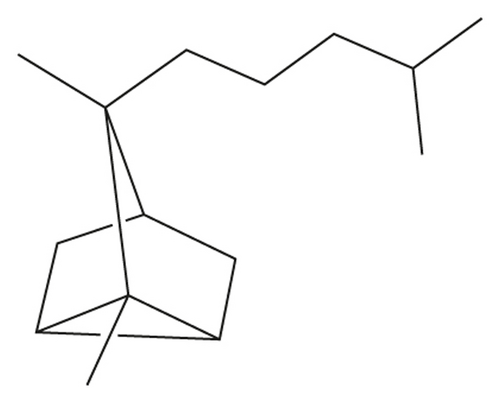

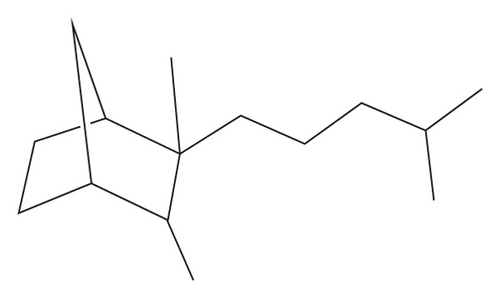

Santalene and santalol are the main components of valuable sandalwood EO obtained by distillation of the heartwood of Santalum species [11]. Santalene sesquiterpene is the precursor substance of santalol which is an important perfumery ingredient with sweet-woody and balsamic odor [12]. In order to get this oil-rich resource, sandalwood natural stands were excessively exploited, but the artificial stands were not easy to be established. This led to a decrease in natural stocks and an increase in market prices [13]. Thus, exploitation of new alternative natural perfume plant resources from other plants is one way to resolve this problem.

Santalane sesquiterpene (α- and β-santalane skeleton, Figure 1) was also identified in Piper guineense and Severinia buxifolia in recent years [14, 15]. Up to now, Clausena lansium (Lour.) Skeels in Hainan Province of China still remained to be an alternate potential plant resource which contains the largest quantity of santalane sesquiterpenes [16]. However, in other Chinese literatures about composition of C. lansium, except for some paper mentioned a small amount (<2%) of them from leaves and fruits [17–21], there were few reports about such abundant santalane sesquiterpene. Thus, more evidence should be found to support the discovery. Besides, leaves of Clausena dunniana H. Lév. collected in Yunnan Province also contained santalanes (>8%) [22], suggesting some santalane sesquiterpenes were also in the relative plants in the same genus. Based on this work, the development of the santalene natural resource from Clausena species was further investigated.

Stored product pests often caused irreversible damage, and psocids were important categories of them. They were small, active, omnivorous insects with short life cycles, high reproductive rates, and long adult lives. Due to the ability to absorb water from the atmosphere, they were widely distributed in several tropical and subtropical countries and often found in extremely high numbers [23]. The booklice Liposcelis bostrychophila Badonnel (Psocoptera: Liposcelidae, LB) had strong adaptability to the environment and is resistant to harmful environmental conditions (tolerant to most insecticides or treatments and easy to recover populations) [24–28]. Chemical treatments were still principal management measures to this storage pest [26]. Many literature demonstrated that some Clausena plants have been proven to exhibit pesticidal properties in both laboratory and field studies against various pests [10]. As early as 1970, Novák carried out the earliest study of pesticidal activities of Clausena plants. He found C. anisata could be used to control Ixodes ricinus [5]. From then on, many scientists focused on the pesticidal activities of Clausena species against health and stored product pests [5, 6, 10]. During our screening for medicinal plants to prevent stored-product pests, the EOs from C. anisum-olens have been confirmed to have bioeffects against LB [29]. Based on the similarity with members of the same genus, whether EOs from other Clausena plants had the same effects deserves further investigation.

Therefore, the aim of this work is to extract the EOs of the other four Clausena plants (C. excavata, C. lansium, C. emarginata, and C. dunniana, respectively) to find santalane sesquiterpenes. The assessment of the lethal (contact toxicity) and sublethal (repellent effects) of the EO and its main compounds is also needed to be tested to control booklice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Samples and Extraction of EOs

The experimental samples of the plants were collected in Guangxi Province, Yunnan Province, and Hunan Province, China, respectively. The plant was identified by Dr. Liu, Q.R. (College of Life Sciences, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China). The specimens were deposited at the Herbarium (BNU) of the College of Resources Science and Technology. The information about the samples is summarized in Table 1. The leaves of the four Clausena species were air-dried. The hydrodistillation was done using a modified Clevenger-type apparatus for 6 h to get the EOs. The extra water was removed out by adding anhydrous sodium sulphate. The EOs were stored in airtight bottles in a refrigerator at 4°C for subsequent experiments.

| Species1 | Origin | Latitude | Longitude | Time | Voucher specimen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clausena excavata Burm. f. | Xishuangbanna, Yunnan Province | 21.99°N | 100.83°E | 2016.03 | BNU-CMH-Dushushan-2016-03-003-001 |

| Clausena lansium (Lour.) Skeels | Yulin, Guangxi Province | 22.66°N | 110.19°E | 2012.07 | BNU-CMH-Dushushan-2012-07-001-001 |

| Clausena emarginata C. C. Huang | Baise, Guangxi Province | 23.34°N | 107.59°E | 2016.03 | BNU-CMH-Dushushan-2016-03-004-001 |

| Clausena dunniana H. Lév. | Chenzhou, Hunan Province | 25.78°N | 113.02°E | 2015.12 | BNU-CMH-Dushushan-2015-12-002-001 |

- 1Name of the four Clausena species in reference to Flora of China.

2.2. Insects

L. bostrychophila (collected from the College of Plant Protection, China Agricultural University, and reared in our laboratory for 2 years) was maintained in the dark incubator at 29 ± 1°C and 70–80% relative humidity. The insects were reared in flasks (50 mL) containing a 10 : 1 : 1 mixture (w/w), by mass, of flour, milk powder, and active yeast wheat. Insects used in all of the experiments were 1 week adults. All the containers housing booklice used in experiments were made escape proof with a coating of polytetrafluoroethylene (Sino-rich®, Beijing Sino-rich Tech Co., Ltd., Xuanwu District, Beijing, China).

2.3. Gas Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry

GC-MS analysis was run on an Agilent 6890 N gas chromatograph equipped on an Agilent 5973 N mass selective detector and using HP-5MS (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) capillary column. The carrier gas was helium with a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The column temperature was programmed at 50°C for 2 min, then increased at 2°C/min to the temperature of 150°C, held for 2 min, and then increased at 10°C/min until the final temperature of 250°C was reached, where it was held for 5 min. The scan range was from 50 to 550 m/z, and the samples were injected at the temperature of 250°C. The injected samples were 1 µL (1% n-hexane solution). The retention indices (RIs) were calculated using a homologous series of n-alkanes (C5–C36) under the same operating conditions. The components were identified by comparing their mass spectra and calculating RI values with those in NIST 05 and Wiley 275 libraries and those published in the literature [30]. Relative percentages of each component in the EOs were obtained by averaging the GC-FID peak area% reports.

2.4. Lethal Effects Experiments

The contact toxicity of the EOs and individual compounds against LB was carried out by the residual film method test as described by Zhao et al. [31]. Myristicin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The test samples of the EOs in different concentrations were prepared in n-hexane. A diameter filter paper (ϕ 5.5 cm) was treated with 300 µL of the solution of the EO. The treated filter papers were stuck in the Petri dish (ϕ 5.5 cm). After they were air-dried to evaporate the solvent completely, the filter paper was carefully fixed on the bottom of the Petri dish. 10 booklice were put on the middle of the filter paper. All the Petri dishes were covered and kept in the incubator. n-Hexane was used as a negative control. Five replicates of each concentration were used. Mortality of insects was observed after 24 h. The LD50 values were calculated by using SPSS 19.0 [32].

2.5. Sublethal Effects Experiments

An area preference method was adopted to assess the repellent activity against L. bostrychophila adults for all EOs [33]. β-Caryophyllene and estragole were obtained from TCI Shanghai Development Co., Ltd. The testing materials were dissolved separately in n-hexane to prepare serials of testing solutions with four comparatively low concentrations (63.17, 12.63, 2.53, and 0.51 nL/cm2). A filter paper (ϕ 5.5 cm) was cut into two equal pieces. 150 μL testing solutions and n-hexane were uniformly painted on each piece. The two pieces of the filter paper were carefully fixed on the bottom of the Petri dish side by side after air-dried.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Composition of the EOs

Hydrodistillation of four different species of Clausena produced yellow-colored oil. The yields of EOs obtained from Clausena genus ranged from 0.03 to 0.67% (Table 2). The constituents were identified by combined GC-FID and GC-MS analysis in the EO of C. excavata, C. lansium, C. emarginata, and C. dunniana. The chemical composition of the four EOs is presented in Table 3. EO from C. dunniana from Hunan Province mostly contained one compound, estragole (99.8%), which suggested that the plant was of estragole chemo type the same as the samples from Guangdong and Yunnan [22, 34, 35]. C. dunniana has been found to possess the highest amounts of estragole since 1987 [35]. This work verified the previous finding that the estragole resource was rich in the EO of C. dunniana from China.

| Species | Sample mass (kg) | Volume (mL) | Yield (v/w%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clausena excavata Burm. f. | 2.0 | 1.3 | 0.06 |

| Clausena lansium (Lour.) Skeels | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.03 |

| Clausena emarginata C. C. Huang | 2.0 | 1.8 | 0.09 |

| Clausena dunniana H. Lév. | 3.0 | 20.1 | 0.67 |

| Compounds | Molecular formula | RI Lit.1 | RI Exp.1 | Identification2 | Relative content (mean values %) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. excavata | C. emarginata | C. lansium | C. dunniana | |||||

| 5-Methyl-3-(1-methylethylidene)-1,4-hexadiene | C10H16 | 1038 | 1038 | RI, MS | — | — | — | — |

| Linalool | C10H18O | 1106 | 1094 | RI, MS | 0.2 | — | — | — |

| Terpinen-4-ol | C10H18O | 1178 | 1179 | RI, MS | — | 0.3 | — | — |

| Estragole | C10H12O | 1196 | 1197 | RI, MS | 1.2 | — | — | 99.8 |

| Elixene | C15H24 | 1359 | 1354 | RI, MS | 9.7 | 1.7 | — | — |

| β-Bourbonene | C15H24 | 1386 | 1385 | RI, MS | 1.0 | — | — | — |

| β-Elemene | C15H24 | 1391 | 1388 | RI, MS | 0.6 | — | — | — |

| β-Cubebene | C15H24 | 1394 | 1389 | RI, MS | 3.0 | 2.7 | — | — |

| α-Santalene | C15H24 | 1414 | 1409 | RI, MS | — | 1.5 | 19.5 | — |

| α-Cedrene | C15H24 | 1416 | 1410 | RI, MS | — | — | 0.6 | — |

| β-Caryophyllene | C15H24 | 1423 | 1420 | RI, MS | 30.7 | 1.0 | 8.3 | — |

| α-Bergamotene | C15H24 | 1433 | 1435 | RI, MS | — | 0.6 | 5.0 | — |

| Aromadendrene | C15H24 | 1437 | 1439 | RI, MS | 2.6 | — | — | — |

| α-Humulene | C15H24 | 1456 | 1454 | RI, MS | — | 2.6 | — | — |

| β-Farnesene | C15H24 | 1459 | 1457 | RI, MS | — | — | 0.3 | — |

| Alloaromadendrene | C15H24 | 1460 | 1461 | RI, MS | — | — | 2.7 | — |

| γ-Muurolene | C15H24 | 1481 | 1475 | RI, MS | 2.7 | — | — | — |

| ar-Curcumene | C15H22 | 1484 | 1480 | RI, MS | — | 5.7 | — | — |

| α-Zingiberene | C15H24 | 1493 | 1492 | RI, MS | — | 32.7 | — | — |

| α-Farnesene | C15H24 | 1505 | 1489 | RI, MS | — | — | 0.5 | — |

| β-Sesquiphellandrene | C15H24 | 1523 | 1501 | RI, MS | — | 0.5 | — | — |

| β-Bisabolene | C15H24 | 1511 | 1504 | RI, MS | — | 0.4 | 3.0 | — |

| γ-Cadinene | C15H24 | 1513 | 1513 | RI, MS | 0.8 | — | — | — |

| Myristicin | C11H12O3 | 1524 | 1527 | RI, MS | — | 15.7 | 1.7 | — |

| δ-Cadinene | C15H24 | 1541 | 1528 | RI, MS | 2.8 | — | — | — |

| Nerolidol | C15H26O | 1539 | 1539 | RI, MS | 0.6 | 0.5 | 6.0 | — |

| Elemicin | C12H16O3 | 1558 | 1566 | RI, MS | — | 0.8 | — | — |

| Spathulenol | C15H24O | 1558 | 1578 | RI, MS | 2.8 | 0.6 | — | — |

| Caryophyllene oxide | C15H24O | 1589 | 1580 | RI, MS | — | — | 2.4 | — |

| Globulol | C15H26O | 1598 | 1583 | RI, MS | 2.6 | 0.5 | — | — |

| Viridiflorol | C15H26O | 1600 | 1590 | RI, MS | 1.3 | — | — | — |

| Humulene epoxide II | C15H24O | 1605 | 1601 | RI, MS | 0.6 | — | — | — |

| Methoxyeugenol | C11H14O3 | 1609 | 1610 | RI, MS | 4.2 | — | — | — |

| τ-Muurolol | C15H26O | 1648 | 1638 | RI, MS | — | 1.6 | — | — |

| Cubenol | C15H26O | 1650 | 1642 | RI, MS | — | 2.4 | — | — |

| β-Eudesmol | C15H26O | 1652 | 1649 | RI, MS | 0.8 | 0.6 | — | — |

| β-Bisabolol | C15H26O | 1672 | 1665 | RI, MS | — | — | 3.1 | — |

| δ-Cadinol | C15H26O | 1673 | 1675 | RI, MS | 1.6 | — | — | — |

| α-Cadinol | C15H26O | 1677 | 1677 | RI, MS | 1.4 | — | — | — |

| α-Santalol | C15H24O | 1678 | 1678 | RI, MS | — | — | 31.7 | — |

| α-trans-Bergamotol | C15H24O | 1693 | 1689 | RI, MS | — | — | 2.1 | — |

| Farnesol | C15H26O | 1695 | 1696 | RI, MS | — | 1.3 | 3.6 | — |

| α-Cuparenol | C15H22O | 1765 | 1776 | RI, MS | — | 0.6 | -- | — |

| n-Hexadecanoic acid | C16H32O2 | 1975 | 1982 | RI, MS | — | — | 1.3 | — |

| Phytol | C20H40O | 2112 | 2119 | RI, MS | 0.7 | — | — | — |

| α-Sinensal | C15H22O | 2323 | 2304 | RI, MS | — | — | 2.9 | — |

| Tetracosane | C24H50 | 2400 | 2400 | RI, MS | 0.5 | — | — | — |

| Octacosane | C28H58 | 2800 | 2800 | RI, MS | 0.6 | — | — | — |

| Hentriacontane | C31H64 | 3100 | 3100 | RI, MS | 0.4 | — | — | — |

| Total | 73.2 | 74.3 | 94.4 | 99.9 | ||||

- 1RI, retention index of the chromatography determined on an HP-5MS column using the homologous series of n-hydrocarbons as reference. 2Identification method: RI, comparison of retention indices with published data and NIST Chemistry WebBook; MS, comparison of mass spectra with those listed in the NIST 05 and Wiley 275 libraries and with published data.

The main compounds of the other three species were sesquiterpenes and their oxygenated derivatives. The differences existed in the chemical composition and content between EOs of the other three species. It was assumed that the discrepancy might have been caused by differences in environmental, individual, and human factors. For example, C. excavate and C. emarginata were mainly dominated by β-caryophyllene (30.7%) and α-zingiberene (32.7%), respectively. The high contents of safrole (75.9%) in C. excavata from reports were in disagreement with this work [36, 37]. Sesquiterpenes were identified as the main type of C. emarginata, leading to a quite opposite result to the sample in Yunnan Province [38].

The results showed that santalane sesquiterpene, α-santalol (31.7%), and α-santalane (19.5%) were totally accounting for over a half (51.2%) of EO from C. lansium. α-Santalene (1.5%) were also identified from C. emarginata. It was the first time to find a large number of santalane sesquiterpene in C. lansium from Guangxi Province and to reveal the presence of α-santalene in C. emarginata, although it was low in content. In previous research, the presence of α- and β-santalol and methyl santalol was detected from the EOs of different organs of C. lansium from Hainan Province [16]. It was found that except for the seeds, the content of α-santalol (0–15.5%) and β-santalol (35–55%) was much more than santalane (0–0.1%). Furthermore, the leaves of C. lansium and C. dunniana from Yunnan Province were collected [22]. The santalane sesquiterpenes in the two plants were less in amount but were more in variety. It was found that C. lansium contained β-santalane (0.12%), α-santalol (1.82%), santalol (12.73%), and β-santalol (0.99%), while C. dunniana had cis-α-santalol (7.96%) and trans-β-santalol (0.30%). The EOs from leaves of C. lansium from Cuba also confirmed the presence of santalane sesquiterpene including (Z)-α-santalol, epi-β-santalol, (Z)-β-santalol, and (E)-β-santalol [39]. Besides, (+)-(E)-α-santalen-12-oic acid and clausantalene were isolated from the C. lansium and C. indica, respectively [40, 41]. Thus, santalane sesquiterpene was found in four Clausena plants (C. lansium, C. emarginata, C. dunniana, and C. indica) by far. These natural santalane sesquiterpenes were potential perfume compound resources and might be utilized to make santalol by synthesis or transformation using chemical and biological methods.

In addition, according to the classification of Swingle and Swingle and Reece, in 1943 and 1967, Clausena, Glycosmis, and Murraya were members of Clauseneae (Aurantioideae) [42, 43]. Comparing with our previous reports about the EOs of Clauseneae [29, 44, 45], the composition from Clausena showed chemical similarity to the other two genera, which provided some evidence to the previous work. Sesquiterpenes were the major compounds in these four species in Clausena genus from China, as well as in Glycosmis and Murraya. Then, some major constituents were in common with the three genera. β-Caryophyllene was the main compound of C. excavate (30.7%) and Murraya species (8.2–27.7%) and was usually found in many Glycosmis plants (G. lucida, G. craibii, G. oligantha, G. esquirolii, and G. pentaphylla); α-zingiberene was the abundant constituent in C. emarginata (32.7%) and Murraya species (2.1–12.7%); and spathulenol was also detected in most of the species in the three genera [44, 45]. However, limited by the sample amount, these results were not able to deduce general taxonomy conclusions to Clauseneae.

3.2. Bioefficacy

The four EOs all showed prominent contact toxicity against the test insect. Among them, C. dunniana exhibited toxicity against LB, with LD50 values of 37.26 µg/cm2, which is only two times less toxic than the pyrethrins. C. lansium and C. emarginata showed similar mortality (69.30 and 69.45 µg/cm2, respectively). Their respective LD50 values are summarized in Table 4.

| Treatments | LD501 (µg/cm2) | 95% fiducial limits (µg/cm2) | Slope ± SE | Chi square (χ2) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. excavata | 103.95 | 97.14–111.24 | 12.47 ± 1.89 | 19.70 | 0.805 |

| C. lansium | 69.30 | 64.76–74.16 | 8.68 ± 0.95 | 22.99 | 0.862 |

| C. emarginata | 69.45 | 66.48–72.43 | 12.16 ± 1.42 | 12.18 | 0.968 |

| C. dunniana | 37.26 | 35.92–38.66 | 13.77 ± 1.45 | 7.39 | 0.999 |

| β-Caryophyllene2 | 74.11 | 71.26–77.75 | 10.40 ± 1.08 | 20.11 | 0.635 |

| Santalol3 | 30.26 | 24.95–35.82 | 3.11 ± 0.50 | 9.79 | 0.711 |

| Myristicin | 130.16 | 124.62–135.39 | 12.67 ± 1.51 | 20.93 | 0.820 |

| Estragole2 | 30.22 | 28.13–32.49 | 8.04 ± 0.96 | 6.25 | 0.995 |

| Pyrethrins4 | 18.72 | 17.60–19.92 | 2.98 ± 0.40 | 10.56 | 0.987 |

After the insects were exposed for 2 h, it was found that the EOs of C. excavate, C. lansium, and C. emarginata exhibited the obvious repellent activity (PR > 90%) against LB at the testing concentrations of 63.17 nL/cm2. The EO of C. lansium showed the best repellent activity than the other three, and it repelled over 90% booklice at 63.17, 12.63, and 2.53 nL/cm2. Even at a relatively lower concentration of 0.51 nL/cm2, the PR values of EO of C. lansium were at the same level of the positive control repellent, DEET (P > 0.05). Moreover, at 4 h after exposure, the EOs of C. lansium and C. emarginata possessed strong repellent activity (PR > 80%) at 63.17 and 12.63 nL/cm2. The results of the repellent activity of the EOs from four Clausena species against LB are presented in Table 5.

| Samples | Mean ± SE (%)1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration (nL/cm2) | ||||||||

| 2 h | 4 h | |||||||

| 63.17 | 12.63 | 2.53 | 0.51 | 63.17 | 12.63 | 2.53 | 0.51 | |

| C. excavata | 100 ± 0a | 78 ± 13ab | 26 ± 3c | 40 ± 15ab | 74 ± 12ab | 32 ± 21c | 24 ± 10cd | 34 ± 15a |

| C. lansium | 98 ± 3a | 98 ± 3a | 98 ± 3a | 68 ± 17a | 96 ± 5a | 88 ± 4ab | 74 ± 12a | −28 ± 12b |

| C. emarginata | 94 ± 3a | 82 ± 8ab | 32 ± 13c | 22 ± 8abc | 92 ± 4ab | 80 ± 8ab | 58 ± 16bc | 46 ± 8a |

| C. dunniana | 30 ± 15c | 12 ± 8c | 42 ± 9bc | 32 ± 19abc | −10 ± 3c | 24 ± 19c | 12 ± 16d | 48 ± 15a |

| β-Caryophyllene | 90 ± 4a | 73 ± 0ab | 42 ± 8bc | 22 ± 5abc | 80 ± 6ab | 44 ± 8bc | 24 ± 13cd | 18 ± 5a |

| Santalol2 | 100 ± 0a | 100 ± 0a | 76 ± 10ab | 32 ± 12abc | 100 ± 0a | 100 ± 0a | 60 ± 12bc | 22 ± 13a |

| Myristicin3 | 60 ± 4b | 50 ± 15bc | 42 ± 14bc | 0 ± 15c | 78 ± 3ab | 48 ± 15bc | 42 ± 14bcd | −22 ± 14b |

| Estragole | 66 ± 6b | 52 ± 20bc | 42 ± 14bc | 12 ± 17bc | 56 ± 16b | 54 ± 12bc | 50 ± 9bc | 28 ± 8a |

| DEET4 | 94 ± 6a | 82 ± 5ab | 86 ± 8a | 70 ± 12a | 92 ± 5ab | 84 ± 3ab | 82 ± 8ab | 54 ± 17a |

- 1Means in the same column followed by the same letters do not differ significantly (P > 0.05) in ANOVA and Tukey’s tests. PR was subjected to an arcsine square-root transformation before ANOVA and Tukey’s tests. 2Data from Zhang et al. (unpublished). 3Data from You et al. [29]. 4Data from Yang et al. [47].

In addition, according to our testing results, contact toxicity of a composition may have some negative correlation with its repellent effect. C. dunniana showed strongest contact toxicity (LD50 = 37.26 µg/cm2), while it exhibited weak activity in repellency assays. On the contrary, C. excavate possessed the weakest contact toxicity (LD50 = 103.95 µg/cm2), but it strongly repelled LB (PR = 100%, 2 h after exposed). These variations were caused by the differences in quality and quantity as well as synergistic effects of composition. As for the EOs of C. lansium and C. emarginata, they had similar contact (69.30 and 69.45 µg/cm2, respectively) and repellent effects (98 and 94%, respectively, P = 0.943).

Our previous papers have already mentioned the active compounds in Clausena plants to control LB. Contact and repellent activities of some major constituents such as estragole, β-caryophyllene, myristicin, p-cymene-8-ol, and santalol against the LB were all confirmed [46, 48]. Here, we retested the data for the β-caryophyllene, myristicin, and estragole and then compared their effects. Santalol and estragole were the two most toxic compounds. Santalol had better activity than EO of C. lansium. As the main compound accounting for 99%, estragole had similar but slightly higher effect than EO of C. dunniana. In repellency tests, santalol repelled 100% LB at the first two concentrations after 2 and 4 h, and it had the same levels with DEET in all testing process (P > 0.05). It was worth noting that there were big differences between the repellent activity of estragole and the EO of C. dunniana in the highest dose of 63.17 (P = 0.05 and 0.00, at 2 and 4 h) and the third dose at 2.53 nL/cm2 (P = 0.410 P=0.410). The difference might be resulting from the room temperature and volatility of the EO. Further research on the compounds from these EOs and the correlation between the two modes of action are quite needed.

4. Conclusions

In this work, the chemical composition of the four Clausena species EOs and their contact and repellent activities against LB were investigated. It is the first time to find a large amount of santalane sesquiterpene in C. lansium from Guangxi Province and to reveal the presence of α-santalene in C. emarginata. Santalane sesquiterpene has been found in four Clausena plants (C. lansium, C. emarginata, C. dunniana, and C. indica) by far. As for the toxicity against LB, it was demonstrated that C. dunniana possessed significant contact effect, while C. excavate, C. lansium, and C. emarginata showed strong repellent effect. The present work exhibited that EOs of Clausena have an excellent potential for application in the management of LB. Clausena plants could be further developed to find more resources of natural products.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program (2016YFC0500805). The authors thank Dr. Z.W. Deng for revising the whole paper.

Open Research

Data Availability

The GC-MS and bioactivity data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.