A Sustainable Manufacturing Strategy from Different Strategic Responses under Uncertainty

Abstract

This paper presents a decision framework that highlights the integration of manufacturing strategy (MS) and sustainability along with strategic responses as a significant component. This integration raises complexity and uncertainty in decision-making following the number of subjective components with their inherent relationships that must be brought into context and the huge amount of required information in eliciting judgments. Thus, a proposed hybrid multicriteria decision-making (MCDM) approach in the form of an integrated probabilistic fuzzy analytic network process (PROFUZANP) is adopted in this work. In this method, analytic network process (ANP) serves as the main framework in identifying policy options of manufacturing strategy. Fuzzy set theory (FST) is used to describe vagueness in decision-making which is carried out by eliciting judgments in pairwise comparisons using linguistic variables with corresponding triangular fuzzy numbers (TFNs). Probability theory is used to handle randomness in aggregating judgments of multiple decision-makers. Results show that a stakeholder-oriented approach is considered the most relevant strategic response in developing a sustainable manufacturing strategy. The contribution of this work lies in identifying the policies which constitute a sustainable manufacturing strategy using an integrated MCDM approach under uncertainty.

1. Introduction

The work of Wickham Skinner in 1969 became the focal point of discussion regarding the role of manufacturing strategy in attaining corporate goals and objectives. Skinner [1] developed the hierarchical top-down strategy framework that links corporate strategy, business strategies, and functional strategies which include manufacturing strategy [2]. This framework eventually became the guidelines of later approaches in this research domain [3–5]. Scholars agree that manufacturing strategy could only support business strategy if a sequence of decisions over structural and infrastructural categories is consistent over a considerable amount of time [6]. Structural decision areas include process technology, facilities, capacity, and vertical integration while infrastructural decision areas contain organization, manufacturing planning and control, quality, new product introduction, and human resources. Each of these decision areas involves a finite number of policy options available to the decision-maker. Certainly, identifying the best policy for each decision area requires careful attention and systems thinking due to the number of decision components that must be taken into consideration which make the decision-making a complex one. Manufacturing strategy has evolved as a diverse field covering theoretical and empirical works across various disciplines; however, the field is criticized over its lack of progress particularly on its integration with current approaches [5] with emphasis on sustainability.

Emerging concerns on sustainability compel manufacturing firms to incorporate in their decision-making processes the interests of the triple-bottom line, that is, economic, environmental, and social issues [7], especially those related to material, energy, and wastes [8, 9] as the primary concerns of manufacturing. Manufacturing industry holds one-third of world energy consumption and CO2 emissions are increasing at a significant rate [10, 11]. Thus, an approach known as sustainable manufacturing was eventually coined by the U.S. Department of Commerce which promotes the idea of having products and processes which are not only profitable, but also safe to the environment and to the society [12]. This gains significant attention from both industry and academia following research agenda in developed economies working toward this direction [13].

This work attempts to provide a framework that integrates manufacturing strategy and sustainable manufacturing with emphasis on considering strategic responses of firms toward sustainability. The proposed framework identifies the policies that must be placed in various manufacturing decision areas with the goal of promoting competitiveness and sustainability which were understated in previous literature in this field. The main departure of this work is the integrative decision-making framework that attempts to holistically capture various decision components with their intrinsic interrelationships. The emphasis on strategic responses was highly motivated by several works, for example, Sweeney [14], Miller and Roth [15], and Frohlich and Dixon [16] together with the work of de Ron [17] and Heikkurinen and Bonnedahl [18]. Sweeney [14] made the first attempt to comprehensively group manufacturing strategies into “generic manufacturing strategies” that include caretaker, marketeer, reorganizer, and innovator strategies. The main idea was that manufacturing organizations, as the result of the complex interactions of organizational culture and values with the options taken by business and manufacturing policies, tend to brand themselves into a specific stance on key decisions in developing manufacturing strategy. This claim was further elaborated by Miller and Roth [15] and was eventually supported by Frohlich and Dixon [16] using different empirical samples. However, with slight modifications, Frohlich and Dixon [16] identified three types of manufacturing strategies that include caretakers, marketeers, and innovators.

Aside from classifying manufacturing strategy types, Sweeney [14] highlighted the notion of transition paths or routes for firms to achieve the most positive form of strategy. These transition paths served as guide for firms on manufacturing policies and competitive advantages they must place to support a particular route. This research domain became prominent following several published works which show consistency of the types of strategic responses. With the onset of growing interests in sustainability, former taxonomies were paralleled by the responses or stances of firms toward sustainability issues as described by the works of de Ron [17] and Heikkurinen and Bonnedahl [18]. Their works highlighted the three strategic responses that firms engage in embracing sustainability issues: stakeholder-oriented, market-oriented, and sustainability-oriented.

This paper attempts to extend previous works on strategic responses by integrating manufacturing taxonomies of Sweeney [14], Miller and Roth [15], and Frohlich and Dixon [16] with the sustainability responses described by de Ron [17] and Heikkurinen and Bonnedahl [18]. This work highlights the framework which introduces two transition routes: first is the stakeholder-oriented→market-oriented→sustainability-oriented route and second is the stakeholder-oriented→sustainability-oriented route. These responses and transition routes are brought into the context of developing a sustainable manufacturing strategy. The goal is to identify the content strategy that addresses both competitiveness and sustainability as the result of these transition routes. Due to the complexity in decision-making, the use of multicriteria decision-making methods (MCDM) particularly analytic hierarchy process/analytic network process (AHP/ANP) becomes appropriate and fundamental. AHP/ANP is a theory of relative measurement that allows decision-makers to structure their decision problems into a hierarchy or a network with subjective components [19, 20]. A number of AHP/ANP applications include computing product sustainability index [21], computing sustainability index with time as an element [22], developing sustainability index for a manufacturing enterprise [23], developing multiactor multicriteria approach in complex sustainability project evaluation [24], evaluating industrial competitiveness [25], evaluating energy sources [26], and developing an AHP-based impact matrix and sustainability-cost benefit analysis [27]. A number of reviews of AHP/ANP application in operations management [28], its methodological development [29], dominant applications [30], and its integration with other operations research tools [31] were conducted.

Following various arguments on the uncertainty of decision-making in the context of AHP/ANP ([32]; Tseng and Chiu [33]), this work adopted the proposed method of Ocampo and Clark [34] coined as PROFUZANP which is based on fuzzy set theory, probability theory, and ANP. In this approach, ANP is used to handle decision-making complexity, FST is used to address vagueness individual decision-maker’s judgment, and probability theory is used to handle randomness of aggregating judgments. The contribution of this work lies in identifying policy options of manufacturing strategy resulting from the strategic responses carried out by manufacturing organizations. This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides an introduction of ANP, fuzzy set theory, and the PROFUZANP approach, Section 3 describes the problem structure, Section 4 presents the results of this study, and finally Section 5 highlights a discussion and conclusion of this work.

2. Methodology

2.1. Analytic Network Process (ANP)

Local eigenvectors are plugged into the supermatrix. The numerical approach of computing the global priority vector is done by normalizing columns and then raising the supermatrix to large powers. This approach enables the supermatrix convergence to a limit value. Each column of the limit supermatrix is a unique positive column eigenvector associated with the principal eigenvalue λmax [36]. This principal column eigenvector resembles the stable priorities of the limit supermatrix and can be used to measure the overall relative dominance of one element over another element in a network structure [37].

2.2. Fuzzy Set Theory (FST)

Zadeh [38] introduced the fuzzy set theory (FST) as a mathematical way in handling imprecision and vagueness in decision-making. In particular, fuzzy numbers provide a way of expressing vagueness in FST. A fuzzy number can be represented by a fuzzy set F = {(x, uF(x)), x ∈ R}, where x takes on any value on the real number line R : −∞ < x < +∞ and uF(x) is a continuous mapping on the closed interval (0, 1). Various forms of a fuzzy number are available but the widely used one is the triangular fuzzy number (TFN) [36, 39]. TFN can be defined as a triplet A = (l, m, u) with a membership function. An introductory discussion of fuzzy numbers and their arithmetic operations can be found in Kaufmann and Gupta [40].

FST is shown to enhance MCDM methods in handling complex and imprecise judgments. Since most evaluators find it hard to elicit numerical judgments, more realistic evaluations use linguistic variables to represent judgment [41]. Linguistic variables have the form of phrases or sentences in a natural language [42]. Tseng [39] argues that linguistic variables can be appropriately associated with corresponding TFNs.

2.3. PROFUZANP Approach

PROFUZANP approach was detailed in the work of Ocampo and Clark [34]; important points are discussed in this section. This approach shares similarity with the works of Tseng [32] which transform TFNs into crisp values before raising the pairwise comparisons matrices to large powers. Since any fuzzy aggregation method requires defuzzification [39], the defuzzification process used by Tseng et al. [43] is derived from the algorithm proposed by Opricovic and Tzeng [44]. The linguistic variables are presented in Table 1 with equivalent TFNs adopted from Tseng et al. [45].

| Linguistic scale | Code | Triangular fuzzy scale | Triangular fuzzy reciprocal scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Just equal | (1, 1, 1) | (1, 1, 1) | |

| Equal importance | EQ | (1/2, 1, 3/2) | (2/3, 1, 2) |

| Moderate importance | MO | (5/2, 3, 7/2) | (2/7, 1/3, 2/5) |

| Strong importance | ST | (9/2, 5, 11/2) | (2/11, 1/5, 2/9) |

| Demonstrated importance | DE | (13/2, 7, 15/2) | (2/15, 1/7, 2/13) |

| Extreme importance | EX | (17/2, 9, 9) | (1/9, 1/9, 2/17) |

The notations used in this paper were lifted from the notations used by works of Tseng [32]. Suppose a set of k decision-makers with as the influence of ith criteria on jth criteria assessed by the kth evaluators.

2.4. Procedure

- (1)

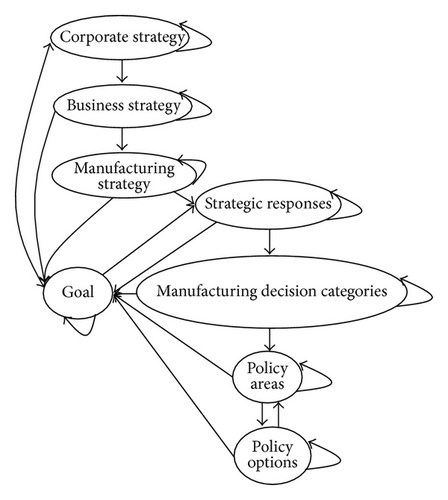

The decision model was established from a rigorous literature review that integrates classical manufacturing strategy and sustainability into a single model. Figure 1 shows the problem structure developed in this work.

- (2)

Respondents were selected to provide expert judgments of the problem structure.

- (3)

Following the AHP/ANP context, pairwise comparisons were performed based on the problem structure. Comparisons were elicited using the linguistic variables in Table 1. Using (4) through (10), corresponding crisp values of the TFNs were computed.

- (4)

Local priority vectors and CI and CR values of pairwise comparisons matrices were computed using (1) through (3).

- (5)

Using (11) through (12) by assigning α = 0.05 and with assigned p = 0.25 which shows the upper limit perturbation of judgments [47], judgments of individual decision-makers were aggregated. Local aggregated priority vectors of these matrices were obtained using (1).

- (6)

An initial supermatrix from the decision model was constructed and then was populated with local eigenvectors obtained in step (4) for each value of p. Normalizing columns and raising the supermatrix to large powers solve the global priority vector.

3. Problem Structure

In reference to the discussion in Section 1, the problem structure is described into two parts. The first part presents the hierarchical structure of corporate strategy, business strategy, and functional strategies. Each component is composed of a number of elements defined in the literature. The second part highlights the influence of strategic responses in developing a manufacturing strategy. This part is supported by the hierarchical structure of decision categories, policy areas, and policy options as described by Wheelwright [48]. A number of policy options comprise a particular policy area and each policy area is composed of a number of finite policy options. This part elucidates the departure of this work from the current literature. Figure 1 presents the problem structure developed in this work.

The problem structure in Figure 1 is composed of eight components which are the goal, corporate strategy, business strategy, manufacturing strategy, strategic responses, manufacturing strategy decision categories, policy areas, and policy options. The model is largely motivated by the hierarchical framework of Skinner [1] with the inclusion of strategic responses as a mediating component that prescribes the content of the manufacturing strategy. Each component comprises a set of decision elements. The goal component contains a single element which is to develop a sustainable manufacturing strategy. Corporate strategy component has two elements: sustainable businesses and commitment to sustainability. Business strategy has likewise two elements: market-oriented and technology-oriented. Manufacturing strategy is a single-element component which is a sustainable manufacturing strategy. Strategic responses component has three elements: stakeholder-oriented, market-oriented, and sustainability-oriented. Manufacturing decision categories component has nine elements and each element has its own set of policy areas as proposed by Wheelwright [48] and Hallgren and Olhager [4]. Likewise, each policy contains policy options available to the manufacturing firm. The objective of this problem structure is to provide the content of a sustainable manufacturing strategy as the result of the overarching problem structure in Figure 1. Using the proposed PROFUZANP approach developed by Ocampo and Clark [34], the proposed model will be able to determine the policy options for each policy area. These options constitute the sustainable manufacturing strategy of the manufacturing firm. In order to facilitate easy recall, a comprehensive coding system is shown in Table 2 to represent each element in the decision model.

| Decision components | Decision elements | Code |

|---|---|---|

| Goal | Develop sustainable manufacturing strategy | A |

| Corporate strategy | Sustainable businesses | D1 |

| Commitment to sustainability | D2 | |

| Business strategy | Market-oriented | E1 |

| Technology-oriented | E2 | |

| Manufacturing strategy | Sustainable manufacturing strategy | F |

| Strategic responses | Stakeholder-oriented | G1 |

| Market-oriented | G2 | |

| Sustainability-oriented | G3 | |

| Manufacturing decision categories | Process technology | C1 |

| Facilities | C2 | |

| Capacity | C3 | |

| Vertical integration | C4 | |

| Organization | C5 | |

| Manufacturing planning and control | C6 | |

| Quality | C7 | |

| New product introduction | C8 | |

| Human resources | C9 | |

| Policy areas | Process choice | C11 |

| Technology | C12 | |

| Process integration | C13 | |

| Facility size | C21 | |

| Facility location | C22 | |

| Facility focus | C23 | |

| Capacity amount | C31 | |

| Capacity timing | C32 | |

| Capacity type | C33 | |

| Direction | C41 | |

| Extent | C42 | |

| Balance | C43 | |

| Structure | C51 | |

| Reporting levels | C52 | |

| Support groups | C53 | |

| System design | C61 | |

| Decision support | C62 | |

| Systems integration | C63 | |

| Defect prevention | C71 | |

| Monitoring | C72 | |

| Intervention | C73 | |

| Rate of innovation | C81 | |

| Product design | C82 | |

| Industrialization | C83 | |

| Skill level | C91 | |

| Pay | C92 | |

| Security | C93 | |

| Job shop | C111 | |

| Batch | C112 | |

| Continuous | C113 | |

| Project | C114 | |

| Robotics | C121 | |

| Flexible manufacturing system | C122 | |

| Computer-aided manufacturing | C123 | |

| Cellular | C131 | |

| Process | C132 | |

| Product | C133 | |

| One big plant | C211 | |

| Several smaller ones | C212 | |

| Close to market | C221 | |

| Close to supplier | C222 | |

| Close to technology | C223 | |

| Close to competitor | C224 | |

| Close to source of raw materials | C225 | |

| Product groups | C231 | |

| Process types | C232 | |

| Life cycle stages | C233 | |

| Fixed units per period | C311 | |

| Based on inputs | C312 | |

| Based on outputs | C313 | |

| Leading | C321 | |

| Chasing | C322 | |

| Following | C323 | |

| Potential | C331 | |

| Immediate | C332 | |

| Effective | C333 | |

| Forward | C411 | |

| Backward | C412 | |

| Policy options | Horizontal | C413 |

| Sources of raw materials | C421 | |

| Distribution to final customers | C422 | |

| Low degree | C431 | |

| Medium degree | C432 | |

| High degree | C433 | |

| Functional | C511 | |

| Product groups | C512 | |

| Geographical | C513 | |

| Top | C521 | |

| Middle | C522 | |

| First line | C523 | |

| Large groups | C531 | |

| Small groups | C532 | |

| Make-to-order | C611 | |

| Make-to-stock | C612 | |

| Close support | C621 | |

| Loose support | C622 | |

| High degree | C631 | |

| Low degree | C632 | |

| High quality | C711 | |

| Low degree | C712 | |

| High frequency | C721 | |

| Low frequency | C722 | |

| High frequency | C731 | |

| Low frequency | C732 | |

| Slow | C811 | |

| Fast | C812 | |

| Standard | C821 | |

| Customized | C822 | |

| New processes | C831 | |

| Follow-the-leader policy | C832 | |

| Specialized | C911 | |

| Not specialized | C912 | |

| Based on hours worked | C921 | |

| Quantity/quality of output | C922 | |

| Seniority | C923 | |

| Training | C931 | |

| Recognition for achievement | C932 | |

| Promotion | C933 | |

In the coding system shown in Table 2, the goal component is assigned as A and corporate strategy as D. Business strategy is denoted as E, manufacturing strategy is represented as F and strategic responses as G, and decision category, policy areas, and policy options components are designated with appropriate alpha-numeric codes of C#, C##, and C###, respectively, with # representing an integer. The coding system in Table 2 is so structured to facilitate remembering of elements associated with their parent element. For instance, C111 represents job shop process and is listed down as the first policy option under C11 policy area which is process choice. C11, on the other hand, also defines the first policy option under C1 manufacturing decision category, process technology.

Respondents were carefully selected with the goal of providing well-informed and expert judgments of the problem structure. Preselection of these respondents was based on their expertise in the manufacturing industry. All domain experts are located in the Philippines who worked for multinational manufacturing firms and were exposed to international practices. In this work, ten experts were selected to provide valid results. Background checks were done for each respondent based on available public data. A threshold criterion is set at least 10-year managerial experience in manufacturing industries to ensure that they have the capability and previous knowledge in carrying out vital manufacturing decisions. This choice of these respondents is consistent with the MCDM studies published by Lin et al. [49], Tseng [32], and Tseng and Chiu [33].

The following steps were undertaken for data gathering required for this work. Questionnaires containing pairwise comparisons matrices were distributed to ten respondents. They were arranged for a supervised survey according to their preferred schedule. However, in a case of a respondent with no available time for a supervised survey or being out of the country, an email containing the survey questionnaire was sent. Respondents were given a maximum of two to four weeks to answer the questionnaire. Within this time period, regular follow-ups were made to ensure timeliness of their output. Upon receipt of their answers, judgment consistency for each pairwise comparisons matrix was checked. When inconsistency was observed, specific matrices were emailed back to the respondent with a note why the matrix is inconsistent. This means that the respondent was informed that his or her judgment on elements a to b and b to c is inconsistent with his or her judgment on a to c. Respondents were given another one or two weeks to reconsider their judgment on specific inconsistent matrices. At this period, regular follow-ups were undertaken.

4. Results

For brevity, the computations carried out in this work are not presented in this paper. All computations were performed using Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and a VBA add-on. A sample pairwise comparisons matrix in linguistic variables from a single decision-maker is shown in Table 3.

| Stakeholder-oriented | Market-oriented | Sustainability-oriented | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stakeholder-oriented | 1/MO | 1/MO | |

| Market-oriented | MO | ||

| Sustainability-oriented |

Note that only the upper triangle of the matrix is filled out as the lower triangle represents the straightforward reciprocal of the upper triangular matrix. This matrix compares the influence of strategic responses in addressing the goal of developing a sustainable manufacturing strategy. From Table 3, corresponding TFNs and their respective reciprocals are shown in Table 4.

| Stakeholder-oriented | Market-oriented | Sustainability-oriented | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stakeholder-oriented | (1, 1, 1) | (2/7, 1/3, 2/5) | (2/7, 1/3, 2/5) |

| Market-oriented | (5/2, 3, 7/2) | (1, 1, 1) | (5/2, 3, 7/2) |

| Sustainability-oriented | (5/2, 3, 7/2) | (2/7, 1/3, 2/5) | (1, 1, 1) |

From the TFNs shown in Table 4, the defuzzification process proposed by Opricovic and Tzeng [44] is used to obtain appropriate crisp values of the TFNs. Crisp values were computed using (4) through (10). Table 5 shows the corresponding crisp values of the sample pairwise comparisons matrix under consideration.

| Stakeholder-oriented | Market-oriented | Sustainability-oriented | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stakeholder-oriented | 1.0000 | 0.3349 | 0.3349 |

| Market-oriented | 2.9863 | 1.0000 | 2.9646 |

| Sustainability-oriented | 2.9863 | 0.3373 | 1.0000 |

Applying the same process to the rest of the decision-makers’ judgments and pairwise comparisons matrices, pairwise comparisons matrices in crisp values are obtained. Aggregation of all judgments across decision-makers is then processed at the pairwise comparisons matrix level. The goal of the aggregation process is to come up with a single matrix that fairly represents the judgments of all decision-makers for a specific pairwise comparisons matrix. Using the proposed PROFUZANP approach of Ocampo and Clark [34] which is also presented in Section 2.3, aggregating judgment of decision makers involves the application of (11) and (12). With α set at 0.05, which is widely used in statistical analysis, and the value of p set at 0.25 following the argument of Hauser and Tadikamalla [47], a sample aggregated matrix of the same set of comparisons is shown in Table 6.

| Stakeholder-oriented | Market-oriented | Sustainability-oriented | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stakeholder-oriented | 1 | 1.521558 | 1.062221 |

| Market-oriented | 0.657221 | 1 | 1.71808 |

| Sustainability-oriented | 0.941424 | 0.582045 | 1 |

From the aggregated matrix, local priority vectors, the principal eigenvalue, and CR value were then computed using (1), (2), and (3), respectively. Table 7 shows a sample of a local eigenvector of an aggregated pairwise comparisons matrix.

| Local eigenvector | |

|---|---|

| Stakeholder-oriented | 0.391017 |

| Market-oriented | 0.331778 |

| Sustainability-oriented | 0.277206 |

- λmax = 3.094; CR = 0.090.

Each column of the limiting pairwise comparisons matrix in Table 8 is the principal eigenvector of the matrix as discussed by Saaty [19]. CR values of all pairwise comparisons matrix are below the 0.10 threshold value. The local priority vectors of all aggregated pairwise comparisons matrices are populated in the supermatrix. The general supermatrix of the decision model presented in Figure 1 is shown in Table 8.

| A | D | E | F | G | C# | C## | C### | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | I | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| D | DA | I | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| E | 0 | ED | I | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F | 0 | 0 | FE | I | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| G | GA | 0 | 0 | GF | GG | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| C# | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | C#G | C#C# | 0 | 0 |

| C## | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | C##C# | I | 1 |

| C### | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | C###C## | I |

The numerical supermatrix runs in the order of 116 × 116; thus it is difficult to present the results here as it consumes large amount of space. For brevity, the generalized supermatrix and the resulting global priority vector are only shown to elucidate the process of the ANP. In order to determine the priority ranking of each policy choice in relation to the goal, Table 9 ranks policy choice according to decreasing global priority values. This ranking provides insights for firms on the sequence of implementation of policy choices. However, this must be taken into context together with business conditions, individual corporate goals, and the propensity of investment decisions of firms. Table 9 provides the ranking of the priority policy choices.

| Code | Decision elements | Global eigenvector | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Develop sustainable manufacturing strategy | 0.323232 | 1 |

| D1 | Sustainable businesses | 0.113131 | 1 |

| D2 | Commitment to sustainability | 0.048485 | 2 |

| E1 | Market-oriented | 0.035479 | 2 |

| E2 | Technology-oriented | 0.045329 | 1 |

| F | Sustainable manufacturing strategy | 0.040404 | 1 |

| G1 | Stakeholder-oriented | 0.085396 | 1 |

| G2 | Market-oriented | 0.05754 | 2 |

| G3 | Sustainability-oriented | 0.038882 | 3 |

| C1 | Process technology | 0.021136 | 1 |

| C2 | Facilities | 0.012683 | 6 |

| C3 | Capacity | 0.017592 | 2 |

| C4 | Vertical integration | 0.009193 | 8 |

| C5 | Organization | 0.011126 | 7 |

| C6 | Manufacturing planning and control | 0.013316 | 5 |

| C7 | Quality | 0.016043 | 3 |

| C8 | New product introduction | 0.013573 | 4 |

| C9 | Human resources | 0.00655 | 9 |

| C11 | Process choice | 0.002177 | 3 |

| C12 | Technology | 0.005874 | 1 |

| C13 | Process integration | 0.002517 | 2 |

| C21 | Facility size | 0.001338 | 3 |

| C22 | Facility location | 0.003449 | 1 |

| C23 | Facility focus | 0.001554 | 2 |

| C31 | Capacity amount | 0.003014 | 2 |

| C32 | Capacity timing | 0.004287 | 1 |

| C33 | Capacity type | 0.001495 | 3 |

| C41 | Direction | 0.002395 | 1 |

| C42 | Extent | 0.001002 | 3 |

| C43 | Balance | 0.0012 | 2 |

| C51 | Structure | 0.0025 | 1 |

| C52 | Reporting levels | 0.0017 | 2 |

| C53 | Support groups | 0.001363 | 3 |

| C61 | System design | 0.003618 | 1 |

| C62 | Decision support | 0.000991 | 3 |

| C63 | Systems integration | 0.002049 | 2 |

| C71 | Defect prevention | 0.005918 | 1 |

| C72 | Monitoring | 0.000949 | 3 |

| C73 | Intervention | 0.001155 | 2 |

| C81 | Rate of innovation | 0.002823 | 1 |

| C82 | Product design | 0.002372 | 2 |

| C83 | Industrialization | 0.001591 | 3 |

| C91 | Skill level | 0.001533 | 1 |

| C92 | Pay | 0.000814 | 3 |

| C93 | Security | 0.000928 | 2 |

| C111 | Job shop | 0.000308 | 2 |

| C112 | Batch | 0.000314 | 1 |

| C113 | Continuous | 0.000264 | 3 |

| C114 | Project | 0.000202 | 4 |

| C121 | Robotics | 0.001173 | 2 |

| C122 | Flexible manufacturing system | 0.00139 | 1 |

| C123 | Computer-aided manufacturing | 0.000374 | 3 |

| C131 | Cellular | 0.000479 | 2 |

| C132 | Process | 0.000583 | 1 |

| C133 | Product | 0.000197 | 3 |

| C211 | One big plant | 0.000484 | 1 |

| C212 | Several smaller ones | 0.000185 | 2 |

| C221 | Close to market | 0.000541 | 1 |

| C222 | Close to supplier | 0.000486 | 2 |

| C223 | Close to technology | 0.000272 | 4 |

| C224 | Close to competitor | 0.000109 | 5 |

| C225 | Close to source of raw materials | 0.000316 | 3 |

| C231 | Product groups | 0.000315 | 1 |

| C232 | Process types | 0.000211 | 3 |

| C233 | Life cycle stages | 0.000251 | 2 |

| C311 | Fixed units per period | 0.000504 | 2 |

| C312 | Based on inputs | 0.000521 | 1 |

| C313 | Based on outputs | 0.000482 | 3 |

| C321 | Leading | 0.001199 | 1 |

| C322 | Chasing | 0.000502 | 2 |

| C323 | Following | 0.000443 | 3 |

| C331 | Potential | 0.000211 | 2 |

| C332 | Immediate | 0.000175 | 3 |

| C333 | Effective | 0.000362 | 1 |

| C411 | Forward | 0.000524 | 1 |

| C412 | Backward | 0.000413 | 2 |

| C413 | Horizontal | 0.00026 | 3 |

| C421 | Sources of raw materials | 0.000385 | 1 |

| C422 | Distribution to final customers | 0.000116 | 2 |

| C431 | Low degree | 8.45E − 05 | 3 |

| C432 | Medium degree | 0.000264 | 1 |

| C433 | High degree | 0.000252 | 2 |

| C511 | Functional | 0.000708 | 1 |

| C512 | Product groups | 0.000372 | 2 |

| C513 | Geographical | 0.00017 | 3 |

| C521 | Top | 0.000244 | 3 |

| C522 | Middle | 0.000331 | 1 |

| C523 | First line | 0.000275 | 2 |

| C531 | Large groups | 0.000313 | 2 |

| C532 | Small groups | 0.000368 | 1 |

| C611 | Make-to-order | 0.001068 | 1 |

| C612 | Make-to-stock | 0.000741 | 2 |

| C621 | Close support | 0.000378 | 1 |

| C622 | Loose support | 0.000118 | 2 |

| C631 | High degree | 0.00085 | 1 |

| C632 | Low degree | 0.000174 | 2 |

| C711 | High quality | 0.002623 | 1 |

| C712 | Low degree | 0.000336 | 2 |

| C721 | High frequency | 0.000417 | 1 |

| C722 | Low frequency | 5.75E − 05 | 2 |

| C731 | High frequency | 0.000432 | 1 |

| C732 | Low frequency | 0.000145 | 2 |

| C811 | Slow | 0.000297 | 2 |

| C812 | Fast | 0.001115 | 1 |

| C821 | Standard | 0.000751 | 1 |

| C822 | Customized | 0.000435 | 2 |

| C831 | New processes | 0.000665 | 1 |

| C832 | Follow-the-leader policy | 0.00013 | 2 |

| C911 | Specialized | 0.000625 | 1 |

| C912 | Not specialized | 0.000141 | 2 |

| C921 | Based on hours worked | 0.000149 | 2 |

| C922 | Quantity/quality of output | 0.000194 | 1 |

| C923 | Seniority | 6.43E − 05 | 3 |

| C931 | Training | 0.000237 | 1 |

| C932 | Recognition for achievement | 0.000134 | 2 |

| C933 | Promotion | 9.21E − 05 | 3 |

Table 10 provides the policy choice for each manufacturing decision area. These policies constitute a sustainable manufacturing strategy. Special attention is also regarded in the prioritization of strategic responses. This sets the type of manufacturing strategy the business would engage. Priority rankings of corporate strategy, business strategy, and strategic responses are presented in Table 11.

| Code | Policy area | Code | Highest priority policy choice |

|---|---|---|---|

| C11 | Process choice | C112 | Batch |

| C12 | Technology | C122 | Flexible manufacturing system |

| C13 | Process integration | C132 | Process |

| C21 | Facility size | C211 | One big plant |

| C22 | Facility location | C221 | Close to market |

| C23 | Facility focus | C231 | Product groups |

| C31 | Capacity amount | C312 | Based on inputs |

| C32 | Capacity timing | C321 | Leading |

| C33 | Capacity type | C333 | Effective |

| C41 | Direction | C411 | Forward |

| C42 | Extent | C421 | Sources of raw materials |

| C43 | Balance | C432 | Medium degree |

| C51 | Structure | C511 | Functional |

| C52 | Reporting levels | C522 | Middle |

| C53 | Support groups | C532 | Small groups |

| C61 | System design | C611 | Make-to-order |

| C62 | Decision support | C621 | Close support |

| C63 | Systems integration | C631 | High degree |

| C71 | Defect prevention | C711 | High quality |

| C72 | Monitoring | C721 | High frequency |

| C73 | Intervention | C731 | High frequency |

| C81 | Rate of innovation | C812 | Fast |

| C82 | Product design | C821 | Standard |

| C83 | Industrialization | C831 | New processes |

| C91 | Skill level | C911 | Specialized |

| C92 | Pay | C922 | Quantity/quality of output |

| C93 | Security | C931 | Training |

| Rank | Strategy | |

|---|---|---|

| Corporate strategy | ||

| 1 | Sustainable businesses | |

| 2 | Commitment to sustainability | |

| Business strategy | ||

| 1 | Technology-oriented | |

| 2 | Market-oriented | |

| Strategic responses | ||

| 1 | Stakeholder-oriented | |

| 2 | Market-oriented | |

| 3 | Sustainability-oriented | |

Priority rankings of corporate strategy, business strategy, and strategic responses are presented in Table 11. The rankings show that sustainable businesses have the highest priority in corporate strategy and a market-oriented business strategy is highly prioritized. Inconsistent with previous works, stakeholder-oriented approach poses most inclination toward developing a sustainable manufacturing strategy.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

Sustainable businesses emerge as a more relevant corporate strategy in addressing sustainability and competitiveness. The difference between sustainable businesses and commitment to sustainability is that the former is a proactive approach where sustainability is embedded in corporate values and culture while the latter takes on a more reactive stance where decision-making depends on how a specific issue will appear. In the business strategy component, technology-orientation (E2) is considered a desirable approach compared to market-oriented approach (E1). The reason for this might be that experts consider technology-orientation as an opportunity to lead an industry into developing environmentally benign technologies with minimum environmental footprint and with less impact on society’s health and well-being. A market-oriented approach on the other hand is limited to the interests of market which is a narrow approach toward sustainability. As opposed to the initial contention that the highest form of manufacturing strategy orientation is a sustainability-orientation [17, 18], results of this work suggest that a stakeholder-orientation in manufacturing serves as a more practical approach in developing a sustainable manufacturing strategy. This result could be viewed from two different perspectives. First, experts likely believe that a better approach in addressing sustainability is hearing the “voice of the stakeholder.” Although it is a reactive stance, this approach ensures that the manufacturing firm addresses each issue of the stakeholders transparently without missing important points along the process. It is particularly similar with the “quality functional deployment” approach in the past; however, a more holistic “voice of the stakeholder” is presented. While a proactive stance in sustainability-orientation is obviously a desirable stance, experts might believe that, in the long run, the manufacturing firms may approach sustainability toward a “strong sustainability” framework where development is very limited. Second, it could be that experts have imprecise knowledge of the contested concepts of sustainability. Since sustainability is still a growing field in the literature with more contestations than a single meaning, experts prefer to give higher priorities to stakeholder-orientation when competitiveness and sustainability are placed into context.

A total of 27 decisions constitute the sustainable manufacturing strategy. Table 10 provides specific policy options corresponding to policy areas. Using the PROFUZANP approach of Ocampo and Clark [34], the decision model provides the content of the sustainable manufacturing strategy. It shows that the content strategy is inclined toward process-centered technology with continuous processes, big, product life cycle stages-focused facilities which are close to suppliers and customers, leading capacity strategy, a backward vertical integration toward sources of raw materials, first-line reporting with functional structure organization, a minimal inventory-focused manufacturing planning and control, high quality prevention, monitoring and intervention policies, fast product introduction with new processes, and highly skilled workers. The content of the sustainable manufacturing strategy is expected to address both competitiveness and sustainability in manufacturing.

Disclosure

An earlier version of this work was presented at the 7th IEEE International Conference on Humanoid, Nanotechnology, Information Technology, Communication and Control, Environment and Management (HNICEM).

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Acknowledgment

L. Ocampo is grateful to the Ph.D. financial support of the Engineering Research and Development for Technology (ERDT) Program of the Department of Science and Technology, Philippines.