The Role of Polarons in Cuprates Hi-Tc Superconductivity

Abstract

The phonon contribution to the phenomenon of high temperature superconductivity in the cuprates is argued as being masked as polarons generated by the polarization of the charge reservoir accompanying the Jahn-Teller tilting of the apical oxygen. We discuss the Mahan oscillator-spring extension model as an analogy to the charge reservoir-CuO plane c-axis polarons. Using the Boltzmann kinetic equation, we show that the polaron dissociates or collapses at a temperature corresponding to the critical temperature of the superconductor.

1. Introduction

Almost three decades since the discovery of high temperature superconductivity in the cuprate La-Ba-CuO by Bednorz and Muller [1] and subsequently in many CuO based compounds by other researchers, there is still no closure about the mechanism of superconductivity in these systems [2, 3]. One of the major points of disagreement is whether phonons contribute along with the accepted spin magnetic fluctuation to the high critical temperature of the cuprates. Many researchers are in support of the phonon mechanism as the only factor responsible for the cuprates high critical temperatures [4–6].

Other workers [7–9] have considered the spin magnetic fluctuation the only adoptable theory for the cuprates. A good reason for the persistence of the “phonon-camp,” is perhaps the enduring success of the electron-phonon interaction (EPI) explanation of the low temperature superconductivity (LTS) by Bardeen, Cooper, and Schrieffer (BCS), [10]. Still another reason may be the recent discovery of superconductivity in MgB3 at Tc = 40 K [11]; this being explained surprisingly by the EPI mechanism. It has even become very comfortable to make prognosis of still higher Tc’s in materials whose electronic properties are well understood based on the EPI. As an example we mention the EPI mechanism used by Gao and his coworkers to predict that the compound Li2B3C superconducts at about 50 K through the process of lifting the σ-bonding up above the Fermi level by doping, enabling σ-electrons to interact strongly with the lattice vibrations in such a way that electron pairing occurs [12]. In the LTS such as lead, tin, and aluminium, phonon contribution is indicated by the isotope effect which relates the critical temperature (Tc) to the mass (M) of the isotope atom as Tc ∝ M−α, where α is the electron-phonon coupling constant defined as α = −dlnTc/dlnM. The BCS value for α is 1/2 [13] which corresponds to the weak coupling regime where the Coulomb interaction is neglected. When the Coulomb interaction is taken into account, α can be approximated by δTc/Tc = −α(δM/M), where α = (1/2)[1 − (μ*/(λ − μ*))] and λ is the BCS interaction parameter. Thus when the isotope shifts δTc and Tc are known, μ* the pseudopotential can be defined [14]. The isotope effect also plays a significant role in the cuprates: La2−xSrxCuO4, YBa2Cu3O7−δ, and Nd2−xCexCuO4, where x is the concentration of strontium and cerium, while δ is the oxygen vacancy. Tunneling measurements on these cuprates support a phonon mediated mechanism of superconductivity [15, 16]. Another angle to the phonon contribution to high temperature superconductivity (HTS) is in terms of polarons. A Landau-Pekar-Frohlich polaron is an electronic perturbation of an ionic crystal such that the polarized lattice interacts and moves with the electron as one entity. The first study of the motion of an electron in an ionic crystal was made by Landau [17]. A series of contributions by many researchers have followed since Landau’s work; significantly, by Pekar, Frohlich, and Feynman (for Pekar’s work, see for example, [18–20]). In recent times the EPI mechanism has been reintroduced into condensed matter physics and applied especially to high temperature superconductivity and colossal magnetoresistance by the use of polarons, with some success [5]. A substantive number of papers have addressed the important questions of polaron mass, its radius, ground state energy, and motion [21–24].

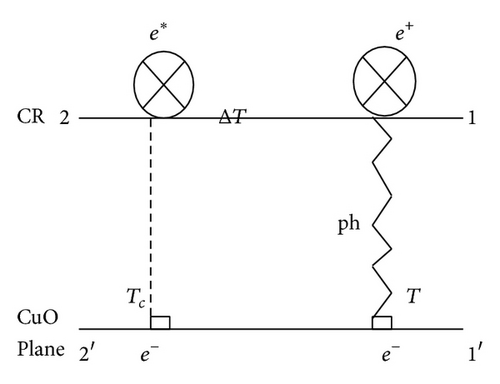

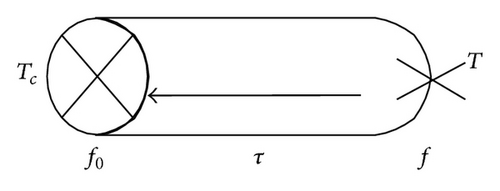

In the present work we shall study polarons in the cuprates in a somewhat different context. The theory we shall propose here consists of the following. Cooper pairs are preformed even in the pseudogap phase; Jahn-Teller tilting of the apical oxygen in the charge reservoir is responsible for the titration of the CuO plane with electrons or holes. The electrons or holes pairings are created by spin fluctuation scenario [7, 9, 25, 26]. Furthermore, every electron or hole that arrives on the CuO plane is polaronic; the Jahn-Teller tilt causes the polarization whose electrical field is responsible for creating phonons that are exchanged between the polarized ions and the electrons on the CuO plane. The exchange of phonons between the polarized ions and CuO paired electrons constitutes polarons of large radii. Two of such polarons connect the CuO plane of, for example, La2−xSrxCuO4, one from above and another from below. Being massive, the polarons trap and localize the Cooper pair, releasing the pair only at the superconducting transition temperature (Tc).

2. Deformation Potential and Lattice Polarization

Here, we chose the limit of integration to reflect a positive direction of electron motion; and are the electron annihilation and creation operators, respectively.

Comparing (14) and (7), we obtain a value of the deformation constant DI as .

3. The c-Axis Polaron

4. Polaron Model of Hi-Tc Superconductivity

In this section we shall discuss our polaron model of superconductivity. We shall begin with the diagram of the model as given below in Figure 1.

The comment made with respect to (36) also holds here.

5. Conclusion

For the stability of the polaron system, its energy ℰpol must be greater than the preformed Cooper pair energy 2Δ in the temperature regime T > Tc. We have assumed that the polarons are localized but oscillating along the c-axis of the cuprate, and when it collapses at T = Tc, the Cooper pair which had also been localized becomes free to make translational motion on the CuO plane. This means that for all polaronic superconductors, ℰpol(T = Tc) = 0. It is this symbiotic relationship between the polaron and Cooper pair that reveals the mechanism of high temperature superconductivity. Furthermore, based on (37), room temperature superconductivity (see, [30]) can be achieved (at least theoretically) by creating a high temperature polaronic cuprate and searching for Tc in it. The higher the polaron temperature is, the higher the likelihood of finding a room temperature Tc.

List of Symbols and Abbreviations

-

- BCS:

-

- Bardeen, Cooper, and Schrieffer

-

- BTE:

-

- Boltzmann transport equation

-

- LTS:

-

- Low temperature superconductors

-

- ωl:

-

- Longitudinal elastic eigenfrequency

-

- :

-

- Phonon annihilation and creation operators at site j

-

- uj:

-

- Atomic displacement

-

- ρ:

-

- Density of the medium

-

- DI:

-

- Deformation constant

-

- 𝒰:

-

- Deformation potential

-

- :

-

- Lattice polarization vector

-

- :

-

- Unit vector of polarization

-

- F:

-

- Polarization strength

-

- ωLO:

-

- Longitudinal optical frequency

-

- α:

-

- Polaron coupling constant

-

- :

-

- Polaron effective mass

-

- m*:

-

- Electron effective mass

-

- ℰpol:

-

- Polaron energy

-

- f(ε):

-

- Fermi-Dirac distribution function

-

- Tc:

-

- Critical temperature

-

- fo:

-

- Equilibrium distribution function

-

- To, T1:

-

- Temperature given by Tc < To < T1, T1 < T

-

- T:

-

- Temperature at which polarons may first appear, the same at which hole or electron pairs are formed

-

- W(k, k′):

-

- Probability of transition from k to k′ in unit time

-

- τ:

-

- Relaxation time

-

- ϵ0:

-

- Static dielectric constant

-

- ϵ∞:

-

- High frequency dielectric constant

-

- ϵ*:

-

- Effective dielectric constant

-

- e:

-

- The electron charge

-

- e*:

-

- The neutral atom.

Conflict of Interests

The author declares that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.