Central Configurations for Newtonian N + 2p + 1-Body Problems

Abstract

We show the existence of spatial central configurations for the N + 2p + 1-body problems. In the N + 2p + 1-body problems, N bodies are at the vertices of a regular N-gon T ; 2p bodies are symmetric with respect to the center of T, and located on the straight line which is perpendicular to the regular N-gon T and passes through the center of T; the N + 2p + 1th is located at the the center of T. The masses located on the vertices of the regular N-gon are assumed to be equal; the masses located on the same line and symmetric with respect to the center of T are equal.

1. Introduction and Main Results

Definition 1 (see [2], [3].)A configuration q = (q1, q2, …, qn) ∈ X∖Δ is called a central configuration if there exists a constant λ such that

For 5-body problems, Hampton [9] provided a new family of planar central configurations, called stacked central configurations. A stacked central configuration is one that has some proper subset of three or more points forming a central configuration. Ouyang et al. [10] studied pyramidal central configurations for Newtonian N + 1-body problems; Zhang and Zhou [11] considered double pyramidal central configurations for Newtonian N + 2-body problems; Mello and Fernandes [12] analyzed new classes of spatial central configurations for the N + 3-body problem. Llibre and Mello studied triple and quadruple nested central configurations for the planar n-body problem. There are many papers studying central configuration problems such as [13–22].

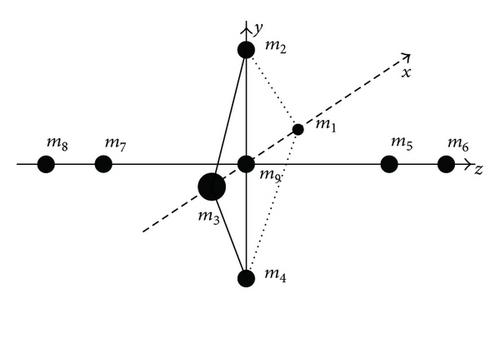

Based on the above works, we study stacked central configuration for Newtonian N + 2p + 1-body problems. In the N + 2p + 1-body problems, N bodies are at the vertices of a regular N-gon T, and 2p bodies are symmetrically located on the same straight line which is perpendicular to T and passes through the center of T; the N + 2p + 1th body is located at the center of T. The masses located on the vertices of the regular N-gon are equal; the masses located on the line and symmetric with respect to the center of T are equal. (see Figure 1 for N = 4 and p = 2).

In this paper we will prove the following result.

Theorem 2. For N + 2p + 1-body problem in R3 where N ≥ 2 and p ≥ 1, there is at least one central configuration such that N bodies are at the vertices of a regular N-gon T, and 2p bodies are symmetric with respect to the center of the regular N-gon T, and located on a line which is perpendicular to the regular N-gon T; the N + 2p + 1th body is located at the center of T. The masses at the vertices of T are equal and the masses symmetric with respect to the center of T are equal.

2. The Proof of Theorem 2

Our approach to Theorem 2 is inspired by the of arguments of Corbera et al. in [23].

2.1. Equations for the Central Configurations of N + 2p-Body Problems

To begin, we take a coordinate system which simplifies the analysis. The particles have positions given by qj = (cos αj, sinαj, 0), where αj = ((j − 1)/N)2π, j = 1, …, N; qN+j = (0,0, rj), qN+j+p = (0,0, −rj), where j = 1, …, p; qN+2p+1 = (0,0, 0).

The masses are given by m1 = m2 = ⋯ = mN = 1, mN+j = mN+j+p = Mj, where j = 1, …, p, mN+2p+1 = M0.

-

, , where j = 1, …, p;

-

ai,j = (1/|ri − rj|2ri − 1/|ri + rj|2ri), when i < j;

-

ai,j = −(1/|ri − rj|2ri + 1/|ri + rj|2ri), when i > j;

-

a0,0 = ai,0 = 1 when i = 1, …, p;

-

b0 = β + M0, , where i = 1, …, p.

2.2. For p = 1

We need the next lemma.

Lemma 3 (see [12].)Assuming m1 = ⋯ = mN = 1, mN+1 = mN+2 = M1, there is a nonempty interval I ⊂ R, M0(r1) and M1(r1), such that for each r1 ∈ I, (q1, …, qN, qN+1, qN+2, qN+3) forms a central configuration of the N + 2 + 1-body problem.

2.3. For All p > 1

The proof for p ≥ 1 is done by induction. We claim that there exists 0 < r1 < r2 < ⋯<rp such that system (12) has a unique solution λ = λ(r1, …, rp) > 0, Mi = Mi(r1, …, rp) > 0 for i = 1, …, p. We have seen that the claim is true for p = 1. We assume the claim is true for p − 1 and we will prove it for p. Assume by induction hypothesis that there exists such that system (12) has a unique solution and for i = 1,2, …, p − 1.

We need the next lemma.

Lemma 4. There exists such that , for i = 1,2, …, p − 1 and is a solution of (12).

Proof. Since , we have that the first p − 1 equation of (12) is satisfied when , for i = 1,2, …, p − 1 and . Substituting this solution into the last equation of (12), we let

By using the implicit function theorem, we will prove that the solution of (12) given in Lemma 3 can be continued to a solution with Mp > 0.

We see that |Ap−1(r1, r2, …, rp−1)|, ap,i and Bp,i for i = 0,1, …, p − 1 do not contain the factor 1/|2rp|2. If we consider |Ap(r1, r2, …, rp)| as a function of rp, then |Ap(r1, r2, …, rp)| is analytic and nonconstant. We can find sufficiently close to such that ≠0 and therefore, a solution (λ, M1, …, Mp) of system (12) is satisfying λ > 0, Mi > 0 for i = 1, …, p.

The proof of Theorem 2 is completed.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Professor Zhang Shiqing for his discussions and helpful suggestions. This work is supported by NSF of China and Youth found of Mianyang Normal University.