Modelling the Influence of Manufacturing Process Variables on Dimensional Changes of Porcelain Tiles

Abstract

A model to study the influence of main process variables (powder moisture, maximum compaction pressure, and maximum firing temperature) on the intermediate variables (mass, dry bulk density, size, and thickness) and the final dimensions of porcelain tiles is proposed. The properties of dried and fired bodies are basically determined by the process parameters when the physical, chemical, and mineralogical characteristics of the raw material are kept constant. For a given set of conditions, an equation could be sought for each property as a function of raw materials and processing. In order to find the relationship between moisture content and compaction pressure with dry bulk density, springback, and drying and firing shrinkage, a laboratory experimental design with three factors and four levels was applied. The methodology was validated in lab scale for a porcelain tile. The final size and thickness were estimated, and the influence of the main process variables was analysed.

1. Introduction

The integration of systems as a requisite to permit a multistage control in the ceramic industry has advanced in the last decades, but it is still behind the traditional chemical industry [1–3]. This is partly because the ceramic sector works with solids, and the level of knowledge in unit operations involving solids has progressed far less than in fluids [4]. The second point that makes automatic control difficult stems from the structural nature of the ceramic product, making the required end characteristics to be multiple and complex, unlike most of the chemical processes in which the most important feature is usually the chemical composition, as revised by Mallol [5]. In the case of ceramic tiles, the end product must meet a number of requirements that range from purely technical characteristics (low porosity and wear resistance) to aesthetic qualities (gloss and design), often restricting the implementation of control systems. Finally, another aspect that makes automation difficult in this type of industry is the wide variety of products that the same company usually needs to produce.

An implementation of techniques of control and automation in the ceramic tile industry would be justified for high value products, which must present a strict tolerance of properties, particularly regarding geometrical dimensions. Among the different types of ceramic tiles that are produced, as defined by the Spanish Ceramic Tile Manufacturers’ Association [6], the porcelain tiles best meet these requirements. A porcelain tile is characterized by low water absorption, usually less than 0.5% for the BIa group [7], high mechanical strength and frost resistance, high hardness, and high chemical and stain resistance, with a broad spectrum of aesthetic possibilities (body colouring with soluble stains, pressed relief, polishing, glazing, etc.), according to a recent review [8].

The usual industrial wet-route processing of porcelain tile covers three main stages: (1) milling/mixing and spray drying of the raw materials, (2) pressing, drying, and decorating of the green body, and (3) firing and classifying of the finished product. The first stage starts with the homogenization and wet milling of raw materials, followed by spray-drying of the resulting suspension. In the second stage, the spray-dried powder with moisture content between 0.05 and 0.07 kg water/kg dry solids is pressed using uniaxial presses at a maximum pressure from 40 to 50 MPa. In the sequence, the resulting body is dried and decorated. Finally, in the third stage, the decorated body is fired in a single-layer roller kiln, using cycles of 40 to 60 min at a maximum temperature from 1180 to 1220°C for obtaining the maximum densification. After firing, the tiles are classified according to aesthetic properties and dimensional aspects, which are naturally related to processing and composition characteristics [9]. Some industries comprise in a single plant the Steps (1) to (3); other ones purchase the granulated powder from a third part processing unit, being restricted to Steps (2) and (3). The latest approach is followed in this paper.

One of the main concerns is related to the dimensional uniformity of the tile (size and form). In the case of size, the manufacturers generally divide the standard tolerance into different categories. The challenge of dimensional control is to produce the highest amount of tiles within a standardized specification to reduce storage lots.

The dimensional changes of ceramic tiles have been broadly studied in the last decades, using different approaches. The final size of fired bodies has been related to the composition of raw materials and/or processing parameters, including preparation, forming, and firing steps. Some of these works could be associated with tentative approaches to provide data for future-automated control of unit operations in the ceramic tile industry. Particularly, pressing and firing steps have been studied more deeply.

The characteristics of an industrial powder and the influence of its particle size distribution on the wet and fired densities were studied by Amorós et al. [10]. Extensive density and porosity measurements were carried out both in the green and the fired states. A proposal was made for the optimization of pressing conditions, including adjustment of pressure if the humidity changes [11]. Any excessive deviation from required dimensions of the fired product might be corrected by adjusting the green density and density distribution, with the help of experimentally determined dependence on moisture content and compacting pressure and on the basis of the relationship between green density and firing shrinkage [12]. Dimensional variations of only 0.1% are enough to cause significant deformations on large tiles. This fault was traced to nonuniform temperature in the preheating zone [13].

A system for effective control of pressing was proposed by Amorós et al. [14], based on modifying maximum pressing pressure to correct the variations in spray-dried powder moisture content, which needs to be measured on line in the pressed bodies. The validity of this method was verified, and it was shown that the maximum fluctuations of moisture content in typical tile manufacturing conditions sometimes exceed the admissible variation for this variable. De Noni Jr. et al. [15] applied a mathematical modelling to quantify the influence of process control variables on the length of fired tile manufactured from raw materials and processes, used by two floor-tile producers. Nevertheless, the influence of the main process variables (compaction pressure and powder moisture) on the final and intermediate characteristics of the tiles (mass, size, and thickness) was not yet accomplished in the literature considering the tile manufacturing process as a whole.

The scope of this work is developing empirical relationships to obtain a model for predicting the final dimensions of tiles (diameter and thickness) in lab scale, taking into account the dimensional changes experienced along the manufacturing steps.

2. Ceramic Tile Manufacturing Process and Variables

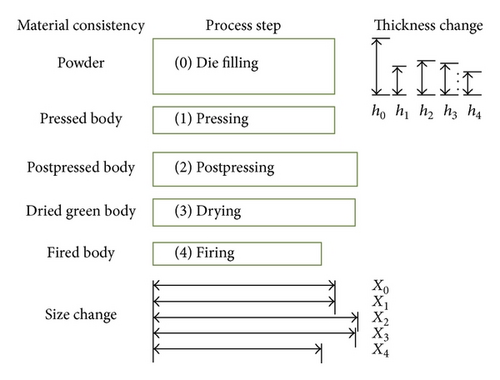

During the manufacturing process, ceramic tiles suffer from dimensional changes in different stages, as shown in Figure 1. Step 0 corresponds to die filling, in which the dimensions (thickness, h, and diameter or length, X) are related to the matrix volumes (h0 and X0). In pressing, Step 1, compaction occurs, the volume decreases, and the body dimensions correspond to h1 and X1, where X1 = X0. After pressing, Step 2, an expansion—also known as springback—takes place. The thermal treatments—drying and sintering (Steps 3 and 4, resp.)—lead to shrinkages.

The dimensional changes experienced by tiles after pressing and drying (postpressing expansion and drying shrinkage, resp.) are determined for a given composition by pressing conditions (powder moisture and maximum compaction pressure, primarily), according to Amorós [16]. The dry bulk density of the tile (directly related to the maximum pressure and powder moisture) and the maximum firing temperature determine the dimensional changes experienced by the tile during firing (firing shrinkage), after studies of Escardino et al. [17]. An equation was obtained by Amorós et al. [18], which calculates the final size of the pieces from their dry bulk density and maximum firing temperature, taking into account the firing shrinkage.

Studies usually focus their attention on the largest of the tile dimensions, the length (X), because it features one of the main properties of the final product’s size. However, since the shrinkage occurs in three dimensions, the final thickness of tiles (h4) is affected by the process variables as well. This parameter is conditioned not only by the dimensional changes experienced by the compacted tile during manufacture (Figure 1), but also by the initial thickness of the bed in the press (h0), that is, the spray-dried powder mass deposited in the press before compacting. Studies have shown the influence of the fill density of press powder beds, which will further affect the final thickness of the ceramic tile [19].

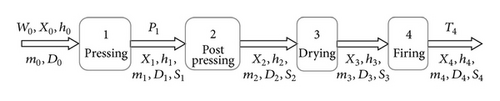

In Figure 2, different variables are shown, which will be taken into account to analyse the volume changes that were undertaken by the ceramic bodies along the processing steps, according to Figure 1.

-

W0: dry-basis spray-dried moisture content (%),

-

X: general characteristic size (mm); in lab-scale it corresponds to diameter of a cylindrical sample and in industrial scale to width or length of rectangular tiles,

-

h: thickness (mm),

-

m: mass (g),

-

D: density (kg/m3),

-

P1: maximum compaction pressure (MPa),

-

S: linear dimensional change based on length or diameter (%),

-

T4: maximum firing temperature (°C).

The subscripts stand for the sequential number related to the respective unit operation. In this work, the variables over the arrow in Figure 2 correspond to independent ones, whose values are fixed, while the variables under the arrow are the dependent ones, whose values are estimated.

In this case, it is assumed that the expansion (S2) and shrinkages (S3 or S4) are independent of the direction. Thus, the body final dimension (R4) may be obtained from the body dimensions after pressing (Step 1), when the values of S2, S3, and S4 are known.

Thus, S2, S3, S4, and D3 may be calculated for a certain composition from the independent variables W0, P1, and T4, using (3) to (6).

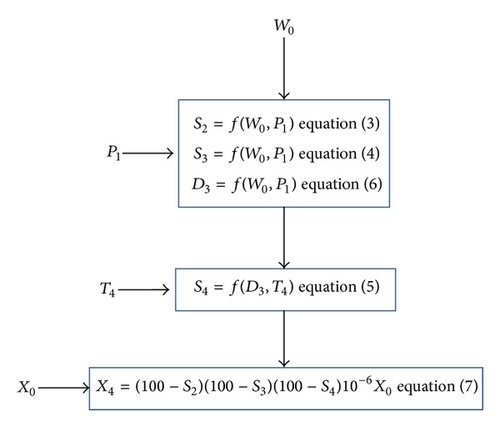

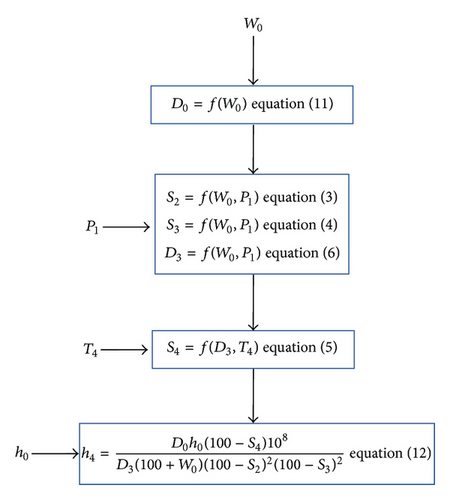

Figure 3 presents flow charts, indicating the sequential steps to calculate the dimensional changes of ceramic tiles (X4 and h4) from independent variables (X0, h0, W0, P1, and T4), and from (3) to (7), (11), and (12).

As stated before, the scope of this work is developing empirical relationships for S2, S3, S4, D0, and D3 to obtain a model for predicting the final dimensions of tiles (diameter and thickness) in lab scale, taking into account the dimensional changes experienced along the manufacturing steps. Furthermore, the influence of the main process variables (compaction pressure and powder moisture) on the final and intermediate characteristics of the tiles (mass, size, and thickness) will be also accomplished.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Raw Materials

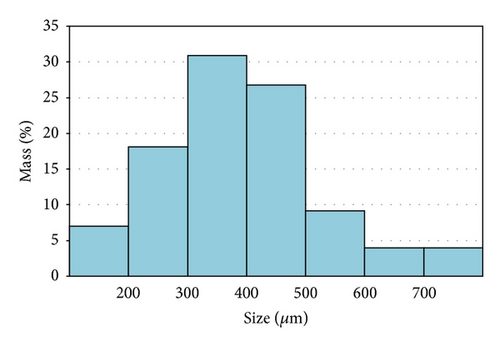

A spray-dried powder with standard porcelain tile composition was used. The particle size distribution is represented in Figure 4. The larger fraction (~60%) corresponds to particles between 300 and 500 μm, as usually employed in the porcelain tile industry.

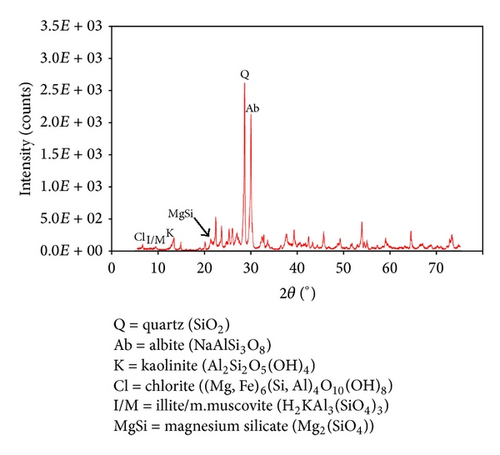

The chemical analysis and X-ray diffraction pattern of the studied ceramic powder are shown in Table 1 and Figure 5, respectively. The main crystalline phases were identified. From the mineralogical and chemical analysis of the samples, a rational analysis was carried out, according to the method developed by Coelho et al. [20]. The percentages of crystalline phases so obtained are presented in Table 2.

| Chemical compound | Mass (%) |

|---|---|

| SiO2 | 65.8 |

| Al2O3 | 20.6 |

| Fe2O3 | 0.66 |

| CaO | 0.66 |

| MgO | 1.34 |

| Na2O | 4.48 |

| K2O | 1.60 |

| MnO | <0.01 |

| P2O5 | 0.09 |

| Loss on fire at 1025°C | 3.91 |

| Crystalline phase | Mass (%) |

|---|---|

| Albite | 38 |

| Quartz | 24 |

| Kaolinite | 18 |

| Muscovite/illite | 14 |

| Chlorite | 5 |

| Other | 1 |

3.2. Experimental Design

Experiments were performed in order to find the regression equations, relating the fill density (D0), dry bulk density (D3), springback (S2), and drying and firing shrinkage (S3 and S4) of porcelain tiles to the independent variables—powder moisture (W0), compaction pressure (P1), and firing temperature (T4)—under constant raw material characteristics. In other words, the aim is to define the functions of (3) to (6) and (12).

An experimental design with 4 levels was initially used to characterize the nonlinear relationship among variables, as shown in Table 3. For each thermal treatment, a combination of pressure and moisture content was applied, and three cylindrical test bodies were pressed.

| Factors | Levels | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| W0 (%) | 3.11 | 4.59 | 5.67 | 7.18 |

| P1 (MPa) | 16.61 | 29.42 | 39.23 | 49.03 |

| T4 (°C) | 1150 | 1176 | 1200 | 1220 |

Since three factors (W0, P1, and T4) and four levels were chosen, a complete experimental design would require 64 experiments without replicates. Considering that the output variables D0, D3, S2, and S3 are related to W0 and P1 but not to T4, a reduced experimental set comprising two factors and four levels was applied.

Test bodies were simultaneously used to find the relation between S4 and the output variables D3 and T4. After drying, all samples were reorganized in four groups, one for each level of temperature. A selection was done, so that each group contained pieces within all ranges of dry bulk density.

3.3. Processing

The processing methodology used closely follows the conventional porcelain tile industrial practice, from pressing to firing stages. However, since the decorating stage is not significant to the dimensional changes, it was not included.

The industrial standard powder was separated into four bags. Each one had the moisture content, adjusted by adding water or drying in a muffle oven. For each W0 and P1, shown in Table 3, three cylindrical specimens (40 × 7 mm) were formed by uniaxial pressing in a hydraulic laboratory press with electronic pressure control (Nannetti), using about 20 g of material for each specimen. Right after body pressing, the sample was weighted, marked, and carefully placed into a bag for 30 min. Then, the diameter, thickness, and bulk density were measured.

After compaction, the test pieces were oven dried at 110 ± 5°C until reaching a constant mass. The moisture content of the bodies was calculated as a difference of mass before and after drying. Afterwards, they were fired in a laboratory electrical kiln (Pirometrol, maximum operating temperature range 1250°C), using heating cycles similar to the industrial practice (fast heating to 500°C and at 25°C/min from 500°C until reaching the maximum temperatures, shown in Table 3). The pieces were kept to the maximum temperature during 6 min. Afterwards, they were cooled with forced air using a fan. The mass, dimensions, and bulk density of the dried and fired samples were measured. The water absorption of the fired bodies was measured additionally. The apparent densities (D2, D3, and D4) of the bodies were measured by the Archimedes immersion method.

The linear shrinkage was calculated from the change in diameter (measured with 0.02 mm resolution digital calliper) of the cylindrical test pieces. Water absorption was determined after immersion in boiling water for 2 h and using a digital analytical scale with a resolution of 0.03 g. The mass of the tiles was measured both before and after immersion to determine the percentage of water absorption.

For determining fill density, the industrial standard powder was adjusted to the selected highest water content by moisturizing. The graduated cylinder was filled by pouring the powder, and the fill density was calculated as the ratio of mass to the cylinder volume. Then, the moisture content was reduced by natural drying. For each value of moisture content, the weighing was made three times with different powders to calculate the experimental error.

3.4. Modelling and Analysis

When the physical, chemical, and mineralogical characteristics of the raw material are kept constant, the properties of dried and fired bodies are basically determined by the process conditions. For a given set of raw materials and processing conditions, an equation could be sought for each property, relating that property with such conditions.

Equations for estimating D3 and S4 are found in the literature [16, 18]. For the remaining variables, new equations were proposed. After analysing different regressions (polynomial, exponential, and logarithmical), the equation which provided the lowest standard deviation of the residuals was chosen, provided that the expected physical behaviour was adequately described.

For each W0 and P1, the response values used in the experimental design represent the average of three measured values, respectively. A regression was fitted to the experimental values, and the regression adequacy was checked. The assumption of normal distribution was proved when the residuals were uncorrelated and randomly distributed with a zero mean value [21]. In most cases, it was known that there was a relation among the three variables.

4. Results and Discussion

This section is structured in two parts. In the first one, (3) to (6) and (11) are presented, which characterize the behaviour of the studied composition in each manufacturing step where dimensional changes occur. In the second one, those equations are used to predict the final diameter (X4) and thickness (h4) in lab scale and to analyse the influence of main process variables (powder moisture (W0) and maximum compaction pressure (P1)) on the intermediate variables (mass, size, and thickness) and the final dimensions of ceramic tiles.

4.1. Equations in Lab Scale

Measured values for D0, S2, D3, and S4 were obtained at the different levels of the three factors W0, P1, and T4, shown in Table 3. The regression equations from (3) to (6) and (11), were fitted with these values, and confidence intervals (CI95%) were calculated. The final results are analysed as follows.

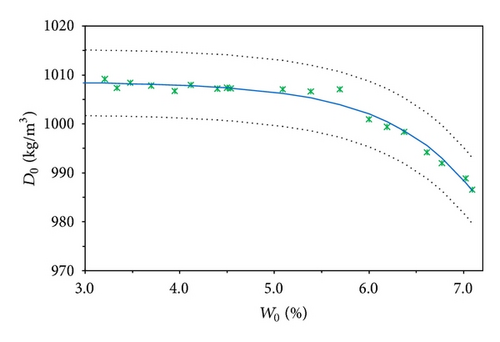

4.1.1. Die Filling

The experimental data are well adjusted by (15). Moreover, the constant B corresponds to the fill density, so that when W0 = 0, D0 ≈ B. From Figure 6, the density decreases as the moisture increases, which is more noticeable for moisture contents >5%. In practice, the mould volume is constant, so that a moisture increase is related to a decrease in the dry powder feed to the mould, especially for W0 > 5%, which is the usual working range for this kind of ceramic tiles. According to Reed [23], the fill density depends directly on the granule density and the packing behaviour.

4.1.2. Pressing

In this section, the adjusted equations corresponding to springback (S2 = f(P1, W0)) and compaction diagram (D3 = f(P1, W0)) are included. Although D3 is the dry bulk density of the green and dried body, that is, after drying, the depending variables in this case are P1 and W0, that is, pressing-related variables. The pressing stage mainly determines D3, so that drying operating parameters (time and temperature) have minor influence [24].

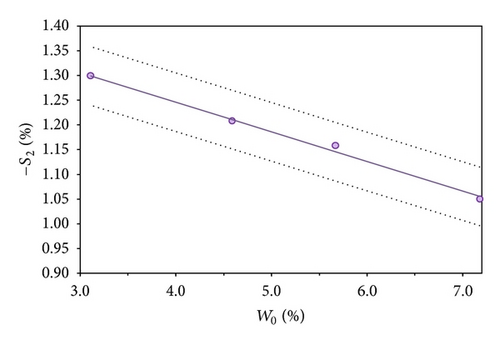

Elastic energy stored in the compacted powder produces an increase in the dimensions of the pressed tile on an ejection, called springback (S2), which may cause compact defects on ejection when in excess. The springback experimental values for the porcelain tile powder used in this study are presented in Table 4 and Figure 7, in which, for convenience, −S2 was used. Those values were measured, considering the difference between the tile size after being taken out from the mould and the pressing matrix constant dimensions.

| −S2 (%) | W0 (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.11 | 4.59 | 5.67 | 7.18 | |

| P1 (MPa) | ||||

| 19.61 | 1.21 ± 0.05 | 1.08 ± 0.04 | 1.07 ± 0.01 | 1.00 ± 0.02 |

| 29.42 | 1.23 ± 0.09 | 1.14 ± 0.04 | 1.10 ± 0.01 | 1.02 ± 0.06 |

| 39.23 | 1.27 ± 0.02 | 1.14 ± 0.09 | 1.14 ± 0.13 | 1.03 ± 0.06 |

| 49.03 | 1.29 ± 0.01 | 1.21 ± 0.04 | 1.16 ± 0.04 | 1.05 ± 0.02 |

It is observed from Table 4 that, as expected, the springback (−S2) increases when P1 is raised and W0 is reduced. The results are consistent with the literature; for the same compaction pressure, −S2 decreases when W0 is increased up to a level of 9% due to the influence of the moisture over the mechanical properties of the spray-dryer granules [16]. It is expected that −S2 rises with increasing values of P1, but this effect is less pronounced at higher W0.

For easy visualization, the relationship between S2 and W0 is shown only at one compaction pressure (for 49.03 MPa) in Figure 7. Upper and lower limits of the curves that correspond to the 95% confidence for the regression at 49.03 MPa are presented as well. Similar curves might be built for remaining pressures from Table 4 and (17) and (18).

4.1.3. Compaction Diagram

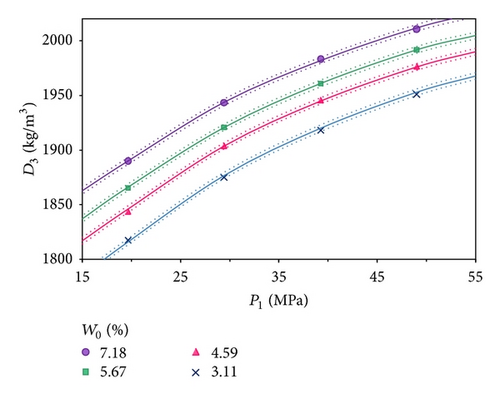

The residuals of the correlation shown in (20) have a mean of −0.39 kg/m3 and a standard deviation of 0.19 kg/m3, values that validate the normality hypothesis.

4.1.4. Drying

Linear drying shrinkage (S3) occurs, as the liquid between the particles is removed and the interparticle separation decreases, and a linear correlation between S3 and W0 might be expected [16]. Shrinkage significantly increases when W0 is raised and slightly decreases when the pressure is increased.

The maximum experimental mean value of S3 was 0.04%, while the standard deviation ranged between 0.01% and 0.07%, resulting in large residual standard deviation (RSD) values, varying between 35 and 1054%. On this basis, the experimental error was considered relatively high.

Additionally, by comparing the orders of magnitude of S2, S3, and S4, it is concluded that the contribution of S3 to the dimensional change is not significant. This result is consistent with the literature data that reports a volume shrinkage in the range of 3–12% for extruded and slip cast parts but 0 for dry-pressed and injection-moulded parts [23].

4.1.5. Firing

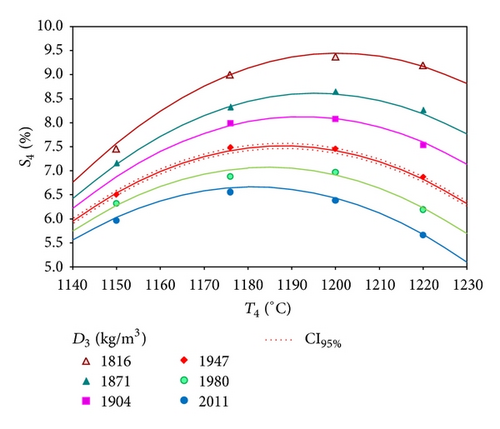

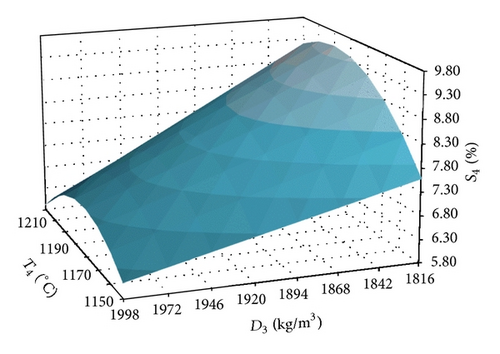

As shown in Figures 9 and 10, for constant D3, when T4 is increased, the linear firing shrinkage (S4) reaches a maximum value and then decreases. The maximum value is reached at a higher temperature as D3 decreases. The same tendency was observed elsewhere [17, 26], owing to the sintering mechanism of porcelain tiles, which includes the decomposition of some clay components generating gases inside the samples causing swelling. After a certain extent, S4 decreases during sintering, since the gases are released [27, 28]. Likewise, for the same T4, S4 increases proportionally to D3, that is, according to the initial porosity. Although only six curves are present in Figure 9, eleven different dry densities were taken into account to adjust the equation.

Porcelain tiles are required to have water absorption values lower than 0.5% [7] as well as to keep the dimensional changes with temperature within a specific range, so that a compromise must be found combining those two properties according to T4 and D3. Lower absorption values are obtained at higher values of T4 and D3.

According to the regression and for a dry bulk density of 1947 kg/m3, a confidence interval of 0.20% was found with a weighted average experimental error of 0.042%. The curves corresponding to the upper and lower limits of the confidence interval (for D3 = 1947 kg/m3) are shown in Figure 9.

4.2. Estimation of Tile Dimensions in Lab Scale and Behaviour Analysis of Intermediate Variables

In this section, the influence of main process variables (W0 and P1) on the intermediate variables (mass, size, and thickness) and on the final dimensions of ceramic tiles was analysed following the study of the model adequacy to estimate the final dimensions (h4 and X4) of ceramic tiles in lab scale.

4.2.1. Estimation of Tile Dimensions in Lab Scale

Using the proposed equations (Section 4.1) and following the scheme presented in Figure 3, the final piece dimension (h4 and X4) was estimated. Those values were calculated for each one of the operational conditions (W0, P1, and T4, presented in Table 3) and the matrix dimensions (h0 = 14.27 mm and X0 = 40.01 mm). The estimated values were compared with measured values. To validate the assumption of normality, the residues were uncorrelated and randomly distributed with a standard deviation and mean value slightly over zero, as presented in Table 5. To validate the methodology, the average of the absolute value of the residuals (the mean absolute error, MAE) was also calculated and compared with the experimental absolute error (EAE). Their values are also presented in Table 5. EAE was calculated as an error associated with the half of the confidence interval with the same probability used through this work (0.95).

Residuals mean (mm) |

Residuals standard deviation (mm) |

Experimental absolute error (mm) |

Mean absolute error (mm) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X4 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| h4 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.50 | 0.14 |

The regression can be considered adequate if the mean absolute error is smaller than the experimental absolute error. That is the case for h4. Although the MAE, for X4, is larger than EAE, its values are close.

4.2.2. Behaviour Analysis of Intermediate Variables

The influence of P1 and W0 on the mass, size, and thickness of the porcelain tile through the manufacturing process was studied following the methodology proposed with the previous equations (Section 4.1). For calculations, the values of h0 and X0 were assumed to be typical lab-scale values (15 mm and 40 mm, resp.).

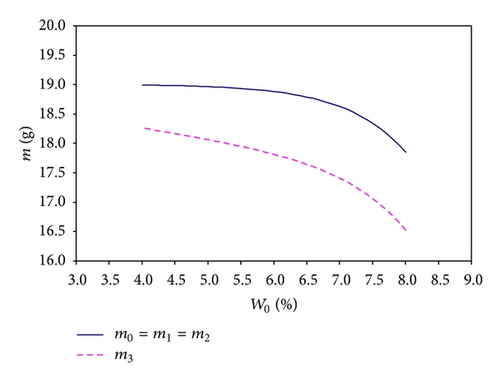

(1) Influence of Powder Moisture on Tile Mass. According to (14), W0 affects D0. During industrial pressing, the volume of the press matrices (X0, h0) is kept constant, so that the variations in D0 will modify the amount of feed powder (m0) and the mass of the green pressed and sintered tile. P1 does not affect the tile mass during the manufacturing process.

In Figure 11, it can be observed that m0 and the dried tile mass (m3) are lower due to the higher W0 and consequent lower D0, caused by the reduced flowability of the powder. This effect is more pronounced for higher moistures, especially for m0, since the variation in bed density is summed up with the water loss after drying. A change in ±0.5% in moisture content, which is usual in industrial practice, will cause a variation of ±0.5% in m0, considering the range of operation moistures to be usually employed (5–7%).

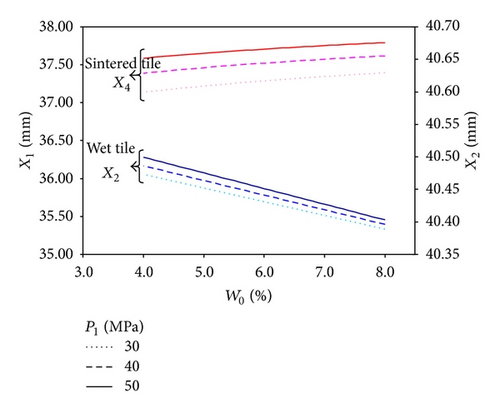

(2) Influence of Powder Moisture and Pressing Pressure on Tile Dimensions. W0 and P1 will affect the size of the wet tile after pressing (X2), the size of the dried tile (X3), and the size of the sintered tile (X4), since X1 = X0. Moreover, considering that X2≃X3, the influence of W0 and P1 on those values is practically the same. In Figure 12, the variation of X2 and X4 is presented as a function of W0 for 3 different P1. For a certain moisture and pressure, the wet tile size is larger than the sintered tile size due to the higher shrinkage (7-8%) compared to the springback (1–1.5%). The influence of W0 is much larger on X4 than on X2, being in both cases a practically linear dependency, in the range of studied powder moisture. The effect of W0 is opposite when wet and sintered tiles are compared: for higher moisture X2 is diminished, while X4 is augmented. In wet bodies, water works as a binder of particles, reducing the elastic response after pressing (lowering the springback) and enhancing D3. When S2 is reduced, the wet bodies present a lower size. When D3 is increased, the bodies present a lower initial porosity, so that sintering shrinkage is lower, and the final dimensions of tiles are higher.

The effect of P1 is similarly much higher on the sintered tiles when compared to the wet tiles. Nevertheless, the influence is directly proportional in both cases, for wet and sintered tiles, in contrast to the effect of W0.

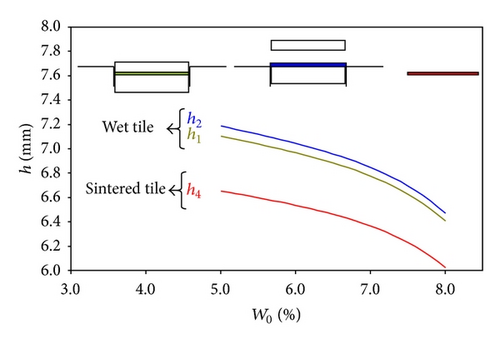

(3) Influence of Powder Moisture and Pressing Pressure on Tile Thickness. In Figure 13, the variation of h1, h2, and h4 as a function of W0 is shown for a P1 of 40 MPa.

As mentioned before, for this particular composition h2≅h3, so that the effect of W0 and P1 will be similar. For higher W0, the tile thickness is reduced, being this effect similar for h1, h2, and h4, since the curves present the same trend. This behaviour is markedly different from the one observed for the size (Figure 12). The variation of the thickness of tiles with W0 seems to depend to a greater extent on the mass variations of the powder fed to the matrix during filling. Indeed, the trends of curves in Figures 13 and 11 are comparable. This indicates that m0 into the press matrix has a larger effect on h than S2 and S4, explaining the behaviour observed in Figure 13.

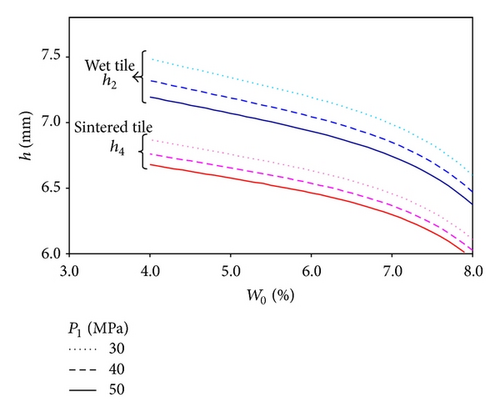

Figure 14 shows the variation of h as a function of W0 for 3 different P1 (30, 40, and 50 MPa). For convenience, only the results for h2 and h4 are presented, since h1 values are similar to those of h2.

For a certain W0, when P1 is increased, the tile thickness is reduced, both for a wet body (h2) and for a sintered body (h4). The effect of pressure is decreased for higher pressure values, since the particles are closer. The influence of pressure on the thickness is higher for the wet body than for the sintered body, since the curves are closer in this case when compared to the curves of the wet body.

5. Conclusions

Empirical equations were obtained correlating the dependent properties to independent variables for fixed raw materials composition and processing conditions.

It was observed that S2, S3, and S4 presented different orders of magnitude, suggesting that the contribution of S3 to the dimensional change is not significant under the studied experimental conditions. The correlations were chosen by the lowest deviation standard value, implying minimal lack of fit and experimental errors. In all cases, the residuals could be considered randomly distributed around a zero mean value, corresponding to a common constant variance and normal distribution.

- (i)

powder moisture content (W0) on fill density (D0),

- (ii)

powder moisture content (W0) and compaction pressure (P1) on springback (S2),

- (iii)

powder moisture content (W0) and compaction pressure (P1) on dry bulk density (D3),

- (iv)

maximum firing temperature (T4) and dry bulk density (D3) on firing shrinkage (S4).

- (i)

when the powder moisture (W0) is increased, the amount of powder fed into the press (m0) is decreased. The same effect, with a higher intensity, is also observed for the dried mass of compacted tiles (m3);

- (ii)

the sizes of green bodies (X2 and X3) are slightly reduced when the powder moisture (W0) is increased, and they augment for higher pressing pressure (P1) as a result of the springback (S2);

- (iii)

the final tile size (X4) is larger for higher powder moisture contents (W0) and the pressing pressure values (P1) due to the increase of density (D3). The effect of both variables on X4 is higher than that on X2 and X3;

- (iv)

the thickness of both green (h1, h2, and h3) and sintered tiles (h4) decreases for lower powder moisture (W0) and pressing pressure (P1).

For the operational conditions considered, the regression equations represent the behaviour of the studied variables at lab scale within a high confidence level. Therefore, before using them to evaluate different press control conditions and strategies, their efficiency should be verified to reproduce industrial data. This is going to be accomplished in a further work, including a computational model to be established according to pressing operational conditions and control strategies in industrial scale. The aim is that the variables of the final product, particularly the tile thickness and size, are kept within a specific quality range.

Acknowledgments

Capes (Coordenação Geral de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, Brazil), DGU (Dirección General de Universidades, Spain), ERDF (European Regional Development Found), and IMPIVA (Instituto de la Mediana y Pequeña Industria Valenciana, Spain) are acknowledged for financial support as well the Spanish producer of ceramic tiles ROCERSA (Roig Cerámica S. A.) for providing raw materials.