Lymphangitic Pulmonary Metastases in Castrate-Resistant Prostate Adenocarcinoma

Abstract

A 63-year-old man with castrate-resistant metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma with known osseous and pelvic nodal involvement presented with progressive dyspnea for one week. Complete cardiopulmonary evaluation revealed a restrictive lung defect that could not be attributed to any of his previous therapies. On presentation, physical examination revealed coarse breath sounds diffusely with hypoxemia. Computed tomography of the chest showed severe bilateral airspace opacities and ground-glass appearance most consistent with interstitial pneumonitis. The patient was intubated due to progressive hypoxemia and worsening respiratory status despite empiric antibiotics and high dose steroids. Subsequent emergent bronchoscopy with transbronchial biopsies revealed atypical intralymphatic cells that stained positively for prostate-specific antigen and prostatic-specific acid phosphatase, confirming the diagnosis of intralymphatic pulmonary metastasis from prostate adenocarcinoma. Lymphangitic pulmonary metastasis from prostate adenocarcinoma is exceedingly rare, with few reported cases that are biopsy-proven. Herein, we describe a rare case of biopsy-proven lymphangitic pulmonary metastasis in the setting of castrate-resistant prostate adenocarcinoma and provide a comprehensive literature review.

1. Case

A 63-year-old man who has metastatic prostate cancer with known osseous and pelvic nodal involvement presented with a one-week history of progressive dyspnea. The patient had presented originally with metastatic disease 5 years prior to admission. He was treated with complete androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) attaining biochemical complete response that lasted for 2 years. Subsequently, he received sipuleucel-T on a clinical trial demonstrating stable disease radiographically for 18 months. Radiographic and biochemical progression necessitated treatment with lenalidomide on a phase II clinical trial. In total, he received 4.5 months of lenalidomide achieving partial biochemical response and stable disease radiographically. However, lenalidomide was discontinued 3 months prior to presentation due to shortness of breath and fatigue attributed initially to the study drug. Pulmonary function testing at that time showed a restrictive pattern and cardiac evaluation was nonrevealing. Dyspnea improved slightly after stopping lenalidomide and further improved with pulse steroids. He subsequently received temsirolimus for 3 weeks before hospitalization with the above-mentioned complaints.

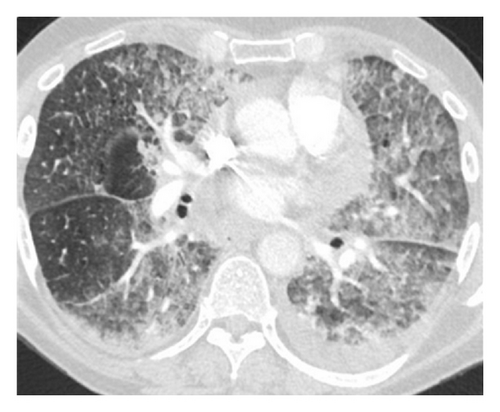

On presentation, physical examination revealed coarse breath sounds bilaterally with hypoxemia. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest showed severe bilateral airspace opacities and ground-glass appearance most consistent with interstitial pneumonitis (Figure 1).

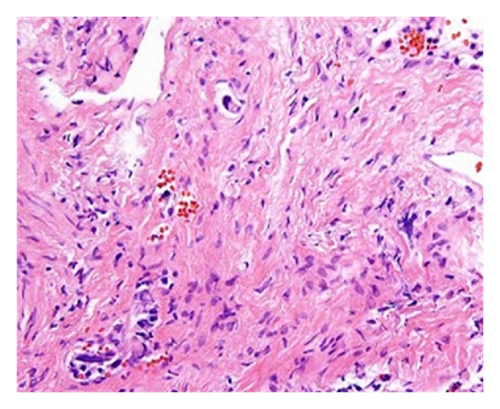

Empiric broad-spectrum antimicrobials and high-dose steroids were initiated but his respiratory status and hypoxemia worsened further. Emergent bronchoscopy revealed normal tracheobronchial trees bilaterally without evidence of inflammation or edema. Transbronchial biopsies revealed atypical intralymphatic cells with abundant cytoplasm and large nuclei with prominent nucleoli (Figure 2).

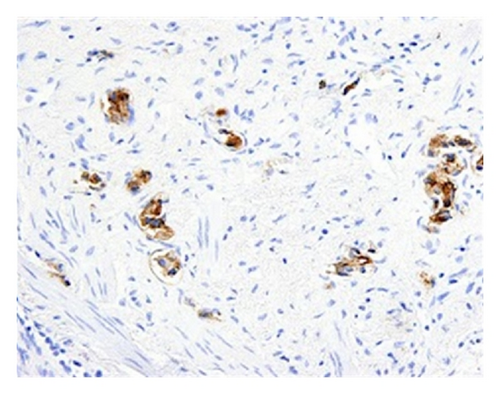

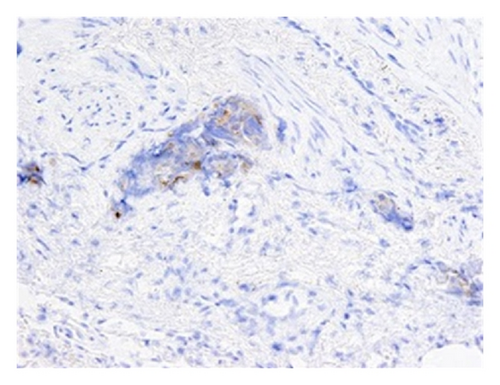

Subsequent immunostains for prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and prostatic-specific acid phosphatase (PSAP) confirmed intralymphatic involvement by prostate adenocarcinoma (Figures 3(a) and 3(b)). While systemic chemotherapy was offered in an attempt to improve his respiratory condition, the family opted for palliative measures, and the patient died 24 hours after extubation.

2. Discussion

Pulmonary lymphangitic carcinomatosis is pathologically described as the presence of tumor thrombi in the lymphatic vessels of bronchovascular bundles, interlobular septa, and pleura [1]. Clinically, the disease process can manifest as progressive dyspnea with subacute cor pulmonale and portends a poor prognosis. Imaging studies characteristically show multiple linear densities forming a reticular network with thickened and irregular bronchovascular bundles. Another common radiographic presentation of pulmonary lymphangitic carcinomatosis is the “tree-in-bud” pattern, which describes bronchiolar luminal impaction that outlines the normally invisible peripheral airway branching. Diagnosis is usually made based on clinical grounds but can be definitively established by obtaining a transbronchial lung biopsy.

In prostate cancer, lymphangitic pulmonary involvement is exceptionally rare, occurring in less than 0.2% of patients [9]. Nodular involvement, however, is more commonly observed. A retrospective review of preoperative chest X-rays for 91 patients with advanced prostate cancer undergoing bilateral orchiectomy revealed 3 patients with bilateral coarse infiltrates consistent with lymphangitic spread [10]. Several cases of presumed pulmonary lymphangitic spread from prostate cancer without confirmatory lung biopsy were identified [5, 11, 12]. Pulmonary lymphangitic spread of prostate cancer that is confirmed pathologically via lung biopsy is rarely reported. To our knowledge, only 7 cases described biopsy-proven lymphangitic metastasis from prostate cancer, but surprisingly none occurred in the castration-resistant setting (Table 1) [2–8]. We describe a rare case of biopsy-proven pulmonary lymphangitic metastasis in the castration-resistant setting.

| Reference | Status of PC at time of lymphangitic spread | Initial pulmonary presentation | Lung biopsy | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miseria et al. [2] | Hormone sensitive | Diffuse interstitial infiltrate with reticulonodular pattern | Done | Clearing of infiltrates with ADT |

| Rossi et al. [3] | Hormone sensitive | Bilateral multiple small nodules | Done | Given ADT, outcome not reported |

| K. S. Miller and J. M. Miller [4] | Hormone sensitive | Diffuse, bilateral, reticulonodular infiltrate | Done | Not reported |

| Cohen et al. [5] | Hormone sensitive | Bilateral interstitial infiltrates | Done | Received ADT followed by chemotherapy with radiographic improvement |

| Heffner et al. [6] | After failing first-line hormonal therapy with DES | Large bilateral effusions with interstitial infiltrate | Done | Second-line hormonal therapy given |

| Arriero et al. [7] | Hormone sensitive | Bilateral interstitial densities with perihilar predominance | Done | Improvement with ADT but suffered SCD of unknown cause 4 months later |

| Schwarz et al. [8] | Developed after failing first-line therapy | Diffuse infiltrations and nodularity | Done | Improvement after orchiectomy |

- ADT: androgen deprivation therapy, DES: diethylstilbestrol, SCD: sudden cardiac death.