Complete Synchronization of Strictly Different Chaotic Systems

Abstract

The criteria for complete synchronization of strictly different chaotic systems using feedback control are presented in this paper. Complete synchronization is achieved when all the states in the slave system are synchronous with the corresponding state in the master system. We illustrate that using a single input and single output control scheme, the synchronization of a class of strictly different systems is obtained in partial form. To overcome this problem we show that a multiple input and multiple output control scheme with an equal number of inputs and outputs than the order system is required in order to obtain the complete synchronization. This procedure is used to synchronize the Rössler and the Chen systems as an example. We also demonstrate that if the synchronization scheme considers less inputs and outputs, the partial-state synchronization is obtained.

1. Introduction

The definition of synchronization is, in general, to make to coincide two or more events at the same time. Applying this universal concept to dynamical systems, we consider the problem of complete synchronization of strictly different systems. We can divide the synchronization problem into two parts: (i) complete synchronization of chaotic systems with equal or similar models and (ii) complete synchronization of strictly different chaotic systems. The former comprises the synchronization of systems whose models are equal or are slightly different but only in parameters. The latter considers the synchronization of chaotic systems whose models have no similarity.

Since chaos synchronization appears in 90s [1], the problem has attracted the attention of the research community. The problem has been studied due to its potential applications, for instance, applications in secure communication [2], in biological systems [3], robotics [4], and more recently the synchronization of complex networks [5, 6].

Chaos synchronization problem has been treated using control techniques where synchronization can be addressed as a tracking or as a stabilization problem. We applied stabilization control techniques instead of tracking issues. Applying these stabilization control techniques to a dynamical system called the synchronization error system, a controller can be designed which renders the stabilization of the error trajectories at the origin. Such a dynamical error system is constructed from the difference between the master and slave systems.

It has been demonstrated that two chaotic systems with the same model even with different parameters can be completely synchronized [7–9]. Once the complete synchronization between systems with same model is solved, a natural question arises: is it possible to completely synchronize two chaotic systems with strictly different models?; The answer is affirmative, however, the problem of synchronizing two chaotic systems with strictly different models can lead to some other chaos synchronization phenomena [10], which depends on the control scheme used. In order to avoid such phenomena and achieve complete synchronization, the control scheme should satisfy certain condition particularly the number of inputs and outputs of the systems and the controllers.

On the other hand, published results show that complete synchronization between two chaotic systems with strictly different models is achieved under the consideration of a Multiple Input and Multiple Output (MIMO) control. However, such results consider MIMO control systems with the number of inputs and outputs equal to the system order, but they do not consider the case where the number of inputs and outputs is less than the system order (ρ < n). In this sense here it is illustrated that partial or generalized synchronization is obtained if ρ < n.

We used the concept of relative degree, observability, and controllability of nonlinear systems to show how a multiple input and multiple output control scheme achieves complete synchronization of strictly different chaotic systems. To begin with, the controller should consider a number of inputs and outputs equal to the system order (ρ = n). However, in some cases the number of inputs and outputs can be strictly less than the systems order. We will demonstrate when is possible to reduce the number of inputs and outputs in such manner that both systems synchronize in complete form. Therefore, we present a procedure to completely synchronize two chaotic systems with strictly different models, for instance, Lorenz and Rössler, Rössler and Chen, and so on. The problem is solved proposing a Multiple Input and Multiple Output (MIMO) control [11]; afterwards, we prove if the control scheme could be relaxed. This is, whether the MIMO control can be reduced to an MIMO control with less number of inputs and outputs. The paper is organized as follows, in the next section the synchronization of strictly different systems is defined and the main contribution is presented, in Section 3, numerical examples are presented to corroborate the results, and in Section 4 some conclusions are provided.

2. Complete Synchronization of Strictly Different Chaotic Systems

As was discussed above chaos synchronization can be addressed as a stabilization problem, which means that the trajectories of the synchronization error have to be stabilized at the origin. First of all, let us consider the definition for a complete chaos synchronization.

Definition 2.1. It is said that two chaotic systems are completely synchronized if the error ∥xM − xS∥ = 0 as t → ∞, where xM, xS ∈ ℝn.

Note that this definition does not depend on the synchronization technique, it is a global definition for complete synchronization [12]. Definition 2.1 means that each state in the slave system is identical or is very close to its corresponding state in the master system along the time. Chaos synchronization can be addressed as a stabilization problem or as a tracking problem. On the one hand, stabilization consists in to find a control command that leads the trajectories of a dynamical system that represents the synchronization error to a particular point which is the origin. whereas, the tracking problem is related to find a control command that makes the slave system trajectories track the trajectories of the master system.

To begin with, consider that strictly different systems referred to those systems that pose vector fields F, G ∈ ℝn with real-valued functions fi and gi all different, for i = 1,2, …, n; otherwise the systems are called partially different.

Now let us consider two same-order strictly different chaotic systems in affine form , yM = CMxM, and , yS = CSxS, where yk are the output vector with k = M, S, F(xk), G(xS) and γi(xS) are smooth vector fields defined in a manifold 𝔐 ∈ ℝn. Now the synchronization error system is given by , and performing the exchange xe = xM − xS, we find the so-called synchronization error system , and ye = Cexe, 𝔉e is defined into an open subset 𝔡 ⊂ 𝔐. Note that the trajectories must be leaded into a small neighborhood δ ⊂ 𝔡 such that the complete synchronization is obtained. The small neighborhood δ is called synchronization manifold and contains the point which is the origin.

In order to lead the synchronization error trajectories of the synchronization error system to the origin via control feedback, ΣE must satisfy local controllability and local observability [11]. In other words both master and slave should be synchronizable (see [13] for details on synchronizability of similar chaotic systems). Moreover, if both master and slave are synchronizable then the synchronization error system is feedback linearizable around . Therefore, the complete chaos synchronization between strictly different systems can be solved by means of a control system that stabilizes every state of the synchronization error system at the origin. To begin with this problem, let us consider the definition of the relative degree which involves the observability and controllability condition for multiple input and multiple output system. From this condition one can determine a set of stabilizing controllers.

Definition 2.2. The Multiple Input and Multiple Output affine system , ye = Cexe, has relative degree vector ρ = (ρ1, ρ2, …, ρn) at the point if:

- (i)

, for all 1 ≤ j, i ≤ n, k < ρi − 1, and for all xe in the neighborhood of ,

- (ii)

the n × n matrix

(2.1)

Remark 2.3. The previous definition for the relative degree is for systems with the same number of inputs and outputs than the order system; therefore, the relative degree matrix is square.

Theorem 2.4. Consider two same order strictly different chaotic systems. If an MIMO control scheme with n inputs and n outputs is used, then complete synchronization as defined in (2.3) is obtained.

Proof. Let us consider that the strictly different systems have n inputs and n outputs; thus, from the definition of the relative degree, one has that there exist control commands that stabilize each state of the synchronization error system at the origin. The transformation z = Φ(xe) = [y1,e, y2,e, …, yn,e] T is such that the transformed synchronization error system is given by

Remark 2.5. Note that in case of the number of inputs and outputs is less than the order system then partial synchronization in the states is obtained.

3. Numerical Results

seeking clarity of the complete synchronization of strictly different systems the result is illustrated by means of two examples, the first one for the case of partial synchronization and the second for complete synchronization; in both cases we consider the Chen system as the master and the Rössler system as the slave.

3.1. Partial Synchronization of Strictly Different Systems

First we show that under certain conditions the synchronization of strictly different systems can lead to partial or generalized synchronization. To begin with, let us consider that the synchronization is carried out by means of a single input and single output control scheme.

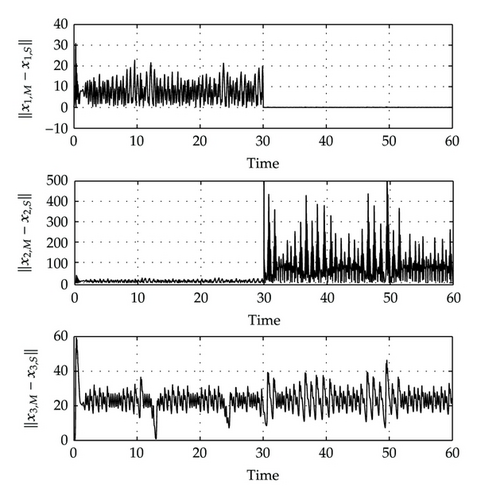

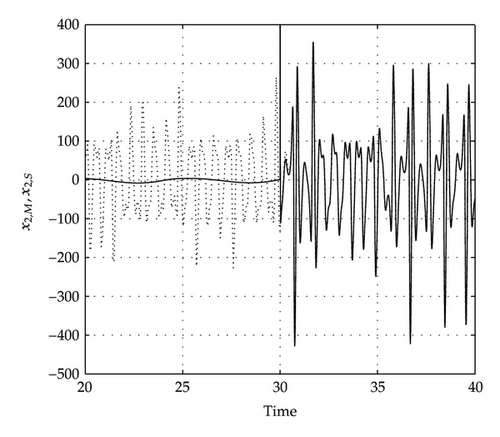

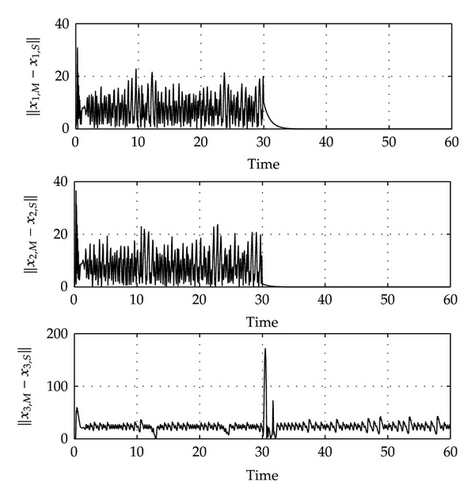

The relative degree is r = 2 and the transformation can be given as , where and ν is the state for the internal dynamics, which is given by . Note that if x1,M − x1,S = 0 and , thus the zero dynamics are obtained and given by . Therefore, the synchronization errors are illustrated in Figure 1. Recall that x2,S is given by the first derivative of the output state, therefore in Figure 2 the functions , and x2,e are plotted, and note that they are equals, which means that x2,S is given by a function of the master system states. It is clear that the synchronization is partial in the states [10], but the main fact is that the unique state that synchronizes is the measured state is; thus, to obtain complete synchronization we look for a transformation whose elements are given by zk = xk,M − xk,S = 0 and no derivatives of the Master and Slave states are involved.

3.2. Complete Synchronization of Strictly Different Systems

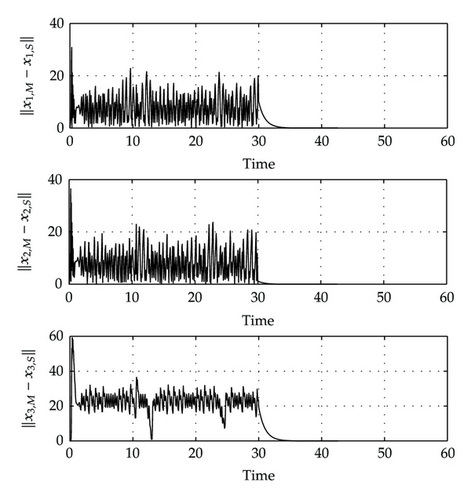

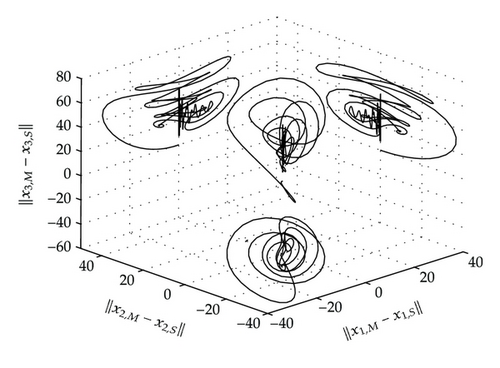

The synchronization errors corresponding to x1,e and x2,e are leaded to zero, this means that the controllers in (3.13) are unable to stabilize the synchronization error trajectories at the origin. In other words the uncontrolled and unobserved state provoke the partial-state synchronization between two strictly different systems. Therefore, to synchronize the Rössler system to the Chen system in the sense of Definition 2.1 is strictly required a MIMO control scheme with an equal number of inputs and outputs than the system order. Note that the third state is not synchronous, and the stabilization of the error trajectories is illustrated in Figure 5, where it can be observed that the synchronization error trajectory is leaded into a thin region, given by an infinitesimal cylinder, which provides synchronization in the x1,e and x2,e axes, this means that the synchronization manifold is deformed in the direction given by the unsynchronized states. It is important to stress that the third state is not free, it is synchronized in a generalized form via the transformation z = Φ(xe).

4. Conclusions

In this work we present the complete synchronization problem between two chaotic systems with strictly different models. We show that both systems cannot be completely synchronized via feedback, using an MIMO control scheme with less inputs and outputs than the system order. Thus using an MIMO control scheme with an equal number of inputs and outputs than the system order and a diffeomorphic transformation obtained from the local controllability and local observability conditions, the complete synchronization is achieved. To determine such a transformation, the synchronization error system outputs are compulsory. Since the control scheme considers a number of control commands and outputs equal to the system order, one can calculate a set of controllers that stabilizes the synchronization errors at the origin. On the other hand, if the control scheme uses a number of control commands and outputs less than the system order, the partial-state synchronization is obtained, as it was illustrated in the second example (see Figure 5). Finally, this result can be considered as the base for the generalization of complete synchronizability of chaotic systems with same order via nonlinear feedback. On the other hand, the result also can be used as a method to determine the generalized synchronization function between states.