Management of Patients Presenting with Acute Subdural Hematoma due to Ruptured Intracranial Aneurysm

Abstract

Acute subdural hematoma is a rare presentation of ruptured aneurysms. The rarity of the disease makes it difficult to establish reliable clinical guidelines. Many patients present comatose and differential diagnosis is complicated due to aneurysm rupture results in or mimics traumatic brain injury. Fast decision-making is required to treat this life-threatening condition. Determining initial diagnostic studies, as well as making treatment decisions, can be complicated by rapid deterioration of the patient, and the mixture of symptoms due to the subarachnoid hemorrhage or mass effect of the hematoma. This paper reviews initial clinical and radiological findings, diagnostic approaches, treatment modalities, and outcome of patients presenting with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage complicated by acute subdural hematoma. Clinical strategies used by several authors over the past 20 years are discussed and summarized in a proposed treatment flowchart.

1. Introduction

Rupture of a cerebral aneurysm normally results in subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) and is often complicated by intracerebral hematoma (ICH), but only on rare occasions does it cause acute subdural hematoma (aSDH) [1]. Diagnosis of aneurysmal SAH can be difficult in comatose patients in whom loss of conscious due to aneurysm rupture results in or mimics a traumatic brain injury [2]. Determining a differential diagnosis and treatment modalities can further be complicated by the rapid clinical course and the mixture of symptoms due to the ruptured aneurysm and the mass effect of the hematoma.

Rapid decision making is required to treat this life-threatening condition. The majority of patients with aneurysmal SAH and coincidental acute subdural bleeding present in a severe clinical condition, and immediate surgical management is required [2–4]. Decisions to be made include whether preoperative diagnostic studies should precede surgery and whether obliteration of the aneurysm should be performed during hematoma evacuation or in a separate delayed intervention after resuscitation procedures.

The incidence of combined SAH and aSDH varies from 0.5% [5, 6] to 10% [7] in clinical series. The rarity of aneurysmal aSDH makes it difficult to design reliable clinical treatment guidelines. Large systematic series do not exist, and thus treatment decisions are mainly based on personal experience. The aim of this review is to propose a management flow chart and protocol based on published experience with such cases over the past two decades.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

The literature was screened for case studies of acute subdural hematoma secondary to ruptured intracranial aneurysm. Articles for this review were identified by MEDLINE PubMed database searches of the literature from January 1990 through December 2009 using the terms “acute subdural hematoma,” “subarachnoid hemorrhage,” and “cerebral aneurysm” (by using the Boolean operator AND) (Table 1). The senior author independently assessed the reproducibility of the search strategy on August 30, 2010, two days after the first author’s search. Cross-references were checked in each eligible article.

| Search number | Process description | Results |

|---|---|---|

| (“key words”) | (no. of articles) | |

| no. 1 | Search “cerebral aneurysm” | 22944 |

| no. 2 | Search “subarachnoid hemorrhage” | 17883 |

| no. 3 | Search “subdural hematoma” | 7732 |

| no. 4 | Search #1 AND #2 AND #3 | 155 |

| no. 5 | Search “01/1990–12/2009” AND #4 | 85 |

- *All searches for this study were performed on August 28, 2010, by the first author and verified by the second author on August 30, 2010. The publication date limits were set to January 1990–December 2009.

2.2. Selection Criteria

Articles were excluded based on title and abstract because they (i) were not written in the English language, (ii) were technical notes or laboratory investigations, or (iii) were not peer-reviewed/original studies. The remaining articles were selected for inclusion if the patients were adults and the single cases or case series provided detailed descriptions of clinical characteristics and patient management.

2.3. Data Acquisition

From selected cases, we extracted the following characteristics and recorded them in a data sheet: age; gender; initial clinical findings, including Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) [8] score, clinical SAH grade based on the Hunt and Hess (H&H) [9, 10], and the World Federation of Neurological Surgeons (WFNS) [11] classifications; presence of major (aphasia, hemiparesis, or hemiplegia) and minor (cranial nerve palsies) focal neurological deficits, hemodynamic situation at the time of admission; radiological assessment, including computed tomography (CT) scan, CT angiography (CTA), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), MR angiography (MRA), and digital subtraction angiography (DSA); additional presence of SAH, intracerebral hematoma (ICH); side and size of aSDH and associated midline shift; aneurysm size and location; case management; outcome according to the Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS), modified Rankin Score (mRS), and Barthel index (BI).

3. Results

The initial search retrieved 85 publications which matched the terms “cerebral aneurysm” AND “subarachnoid hemorrhage” AND “acute subdural hematoma.” 59 publications were excluded after screening of titles and abstracts. This left 26 articles potentially eligible for detailed evaluation. Six articles were not included as they did not match the selection criteria. The remaining 20 articles including 82 cases underwent detailed analysis [2–4, 12–14, 16–26, 28–30]. Characteristics of the 82 cases are summarized in Table 2. Graphs displaying the analyzed data appear in Figure 1.

| Series/year of publication | Case no. | Age/sex | Initial clinical findings | Initial diagnostics | SAH | ICH | Side of aSDH | Size of aSDH | MLS | Location of aneurysm | Size of aneurysm | Management (hours from ictus) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Watanabe et al. [30]/1991 | 1 | 51/m | WFNS 5, GCS 4, decerebrate posture, bilaterally dilated fixed pupils ataxic breath | CT scan | No | No | Lt | — | — | Lt Pcal (ACA) | — | Emergency craniectomy and hematoma evacuation (1 h) | Deceased, GOS 1, mRS 6 |

| Watanabe et al. [30]/1991 | 2 | 72/f | WFNS 4, GCS 12, right hemiparesis | CT scan, DSA | Yes | No | Lt | — | — | Rt Pcal (ACA) | — | Clipping (on day 15) | Returned to normal daily life, GOS 5, mRS 1 |

| Watanabe et al. [30]/1991 | 3 | 74/f | WFNS 5, GCS 4, decerebrate posture, ataxic breath, dilation of the left pupil | CT scan, DSA failed | Yes | No | Rt | — | — | Lt Pcal (ACA) (found at autopsy) | — | Inoperable | Deceased (3 days after onset), GOS 1, mRS 6 |

| Kamiya et al. [5]/1991 | 4 | 67/f | H&H IV, paresis | CT scan, DSA | Yes | No | — | — | — | MCA | 30 mm | Craniotomy, hematoma evacuation, and immediate clipping | Vegetative state, GOS 2, mRS 5 |

| Kamiya et al. [5]/1991 | 5 | 50/f | H&H III | CT scan, DSA | Yes | Yes | — | — | — | ICA | 28 mm | Inoperable because of rerupture on admission | Decubitus and pneumonia, deceased, GOS 1, mRs 6 |

| Kamiya et al. [5]/1991 | 6 | 67/f | H&H V, paresis | CT scan, DSA | Yes | Yes | — | — | — | MCA | 4 mm | Inoperable | Deceased (on arrival), GOS 1, mRs 6 |

| Kamiya et al. [5]/1991 | 7 | 52/f | H&H V | CT scan, DSA | Yes | Yes | — | — | — | Not detected | — | Inoperable | Deceased (on arrival), GOS 1, mRs 6 |

| Kamiya et al. [5]/1991 | 8 | 69/f | H&H II | CT scan, DSA | Yes | Yes | — | — | — | Acom | 27 mm | Inoperable because of severe spasm on admission | Deceased, GOS 1, mRs 6 |

| Kamiya et al. [5]/1991 | 9 | 63/f | H&H II | CT scan, DSA | Yes | No | — | — | — | MCA | 4 mm | Craniotomy, hematoma evacuation, and immediate clipping | Good recovery, GOS 5, mRs 1 |

| Kamiya et al. [5]/1991 | 10 | 73/m | H&H IV, paresis | CT scan, DSA | Yes | No | — | — | — | Acom | 7 mm | Clinical deterioration, no operation impossible | Deceased, GOS 1, mRs 6 |

| Kamiya et al. [5]/1991 | 11 | 64/m | H&H V, preoperative rerupture, cardiac failure | CT scan, DSA failed | Yes | No | — | — | — | Not detected | — | Inoperable | Deceased (nonfilling state DSA), GOS 1, mRs 6 |

| Kamiya et al. [5]/1991 | 12 | 72/f | H&H IV, paresis | CT scan, DSA | Yes | Yes | — | — | — | Distal ACA | 4 mm | Hematoma evacuation and immediate clipping | Good recovery, GOS 5, mRs 1 |

| Kamiya et al. [5]/1991 | 13 | 70/m | H&H IV, paresis | CT scan, DSA | Yes | Yes | — | — | — | MCA | 6 mm | Hematoma evacuation and immediate clipping | Good recovery, GOS 5, mRs 1 |

| Kamiya et al. [5]/1991 | 14 | 72/f | H&H V | CT scan, DSA | Yes | Yes | — | — | — | ICA | 4 mm | Inoperable | Deceased (day 1), GOS 1, mRs 6 |

| Kamiya et al. [5]/1991 | 15 | 59/m | H&H V | CT scan, DSA | Yes | Yes | — | — | — | MCA | 22 mm | Inoperable | Deceased (day 2), GOS 1, mRs 6 |

| Kamiya et al. [5]/1991 | 16 | 39/f | WFNS 5, GCS 4, decerebrate posturing, dilation of the right pupil | CT scan, DSA | Yes | Yes | — | — | Moderate to marked | Distal ACA | 3 mm | Hematoma evacuation and immediate clipping | Good recovery, GOS 5, mRs 1 |

| Kamiya et al. [5]/1991 | 17 | 71/f | H&H III | CT scan, DSA | Yes | Yes | — | — | — | Acom | 11 mm | Hematoma evacuation and immediate clipping | Good recovery, GOS 5, mRs 1 |

| Rusyniak et al. [12]/1992 | 19 | 74/f | WFNS 5, GCS 4, decerebrate posturing, bilaterally miotic pupils | CT scan, CTA | Yes | Yes | Rt | — | — | Rt ICA-Pcom | — | Hematoma evacuation, immediate clipping | Complete recovery, GOS 5, mRS 1 |

| Ragland et al. [13]/1993 | 20 | 27/m | GCS 5 right pupil nonreactive left mydriasis | CT scan, DSA | No | no | Rt | — | Moderate to marked | Acom | 20 mm | Hematoma evacuation, Maximal medical treatment | Deceased, GOS 1, mRS 6 |

| O’Sullivan et al. [3]/1994 | 21 | 32/m | WFNS 5, GCS 4, bilaterally fixed pupils, hypertensive with bradycardia | CT scan | Yes | — | Lt | — | — | Lt ICA-Pcom | 12 mm | Mannitol, without effect on pupillary response (3 h), died before decompression | Deceased, GOS 1, mRS 6 |

| O’Sullivan et al. [3]/1994 | 22 | 48/f | WFNS 5, GCS 4, dilated unreactive pupils, unstable cardiopulmonary situation | CT scan, DSA | Yes | Yes | Rt | — | — | Rt ICA-Pcom | 15 mm | Manitol, without effect on pupillary response, hematoma evacuation, and clipping of the aneurysm (7 h) | Deceased, GOS 1, mRS 6 |

| O’Sullivan et al. [3]/1994 | 23 | 36/f | WFNS 5, GCS 3, bilaterally fixed pupils | CT scan, DSA | Yes | Yes | Rt | — | — | Rt MCA | 12 mm | Hematoma evacuation (4 h) and delayed clipping (day 4) | Residual mild left hemiparesis, returned to work as a teacher, GOS 4, mRS 3 |

| O’Sullivan et al. [3]/1994 | 24 | 63/f | WFNS 5, GCS 3, dilated unreactive pupils | CT scan, DSA | Yes | — | Rt | — | — | Rt ICA-Pcom | 20 mm | Hematoma evacuation (4 h) and delayed clipping (day 7) | Full recovery, returned to normal lifestyle, GOS 5, mRS 1 |

| O’Sullivan et al. [3]/1994 | 25 | 62/f | WFNS 3, GCS 14, mild left hemiparesis | CT scan, DSA | Yes | No | Rt | 20 mm | — | Rt ICA-Pcom | 4 mm | Hematoma evacuation and immediate clipping | Uneventful recovery, returned to normal lifestyle, GOS 5, mRS 1 |

| Nowak et al. [14]/1995 | 26 | 52/f | WFNS 5, GCS 3, dilated unreactive pupils, hypertensive crisis (systolic BP 280 mmHg) | CT scan | Yes | No | Rt | — | — | Rt Pcal (ACA) | — | Manitol, emergency hematoma evacuation | Deceased, GOS 1, mRS 6 |

| Nowak et al. [14]/1995 | 27 | 45/f | WFNS 1, GCS 15, disturbances of vision | CT scan, DSA | Yes | Yes | Rt | 10 mm | — | Rt MCA | — | Hematoma evacuation and clipping (day 1) | Full recovery, returned to normal lifestyle, GOS 5, mRS 1 |

| Nowak et al. [14]/1995 | 28 | 49/f | WFNS 5, GCS 3, mild left-sided hemiparesis | CT scan | Yes | — | Rt | — | Marked | Rt MCA | >25 mm | Emergency hematoma evacuation with gluing of the aneurysm | Deceased, GOS 1, mRS 6 (rebleeding) |

| Nowak et al. [14]/1995 | 29 | 63/m | WFNS 5, GCS < 6, right dilated pupil | CT scan, DSA | Yes | — | Rt | — | — | Rt MCA | 10 mm | Immediate hematoma evacuation and delayed clipping (week 5) | Full recovery, no serious neurological deficits, GOS 5, mRS 1 |

| Ishibashi et al. [15]/1997 | 30 | 54/f | WFNS 1, GCS 15, no neurological deficit | CT scan, DSA | No | No | Lt | — | — | Lt ICA-PCom | — | Craniotomy, hematoma evacuation, and immediate clipping (<24 h) | No neurological deficit, return to normal life, GOS 5, mRS 1 |

| Nonaka et al. [16]/2000 | 31 | 52/f | GCS 4, decerebrate rigidity, and left oculomotor paresis | CT scan, DSA | No | No | Lt | — | Moderate to marked | Lt ICA-PCom | 10 mm | Craniotomy, hematoma evacuation, and immediate clipping (>24 h) | Full recovery, no neurological deficits, GOS 5, mRS 1 |

| Inamasu et al. [17]/2002 | 32 | 68/m | WFNS 2, GCS 14, H&H II | CT scan, DSA | Yes | No | — | <25 cc | <5 mm | Acom | — | Craniotomy, hematoma evacuation, and immediate clipping (6 h) | Good recovery, GOS 5, mRs 1 |

| Inamasu et al. [17]/2002 | 33 | 61/f | WFNS 4, GCS 10, H&H IV | CT scan, DSA | Yes | Yes | — | <25 cc | <5 mm | Rt MCA | — | Craniotomy, hematoma evacuation, and immediate clipping (6 h) | Good recovery, GOS 5, mRs 1 |

| Inamasu et al. [17]/2002 | 34 | 75/f | WFNS 4, GCS 11, H&H IV | CT scan, DSA | Yes | Yes | — | <25 cc | <5 mm | Lt MCA | — | Craniotomy, hematoma evacuation, and immediate clipping (6 h) | Severe disability, GOS 3, mRS 5 |

| Inamasu et al. [17]/2002 | 35 | 28/f | WFNS 5, GCS 5, H&H IV | CT scan, | No | No | Rt | <25 cc | >10 mm | Lt ICA-Pcom (autopsy) | — | Craniectomy and hematoma evacuation | Deceased (5 days after admission), GOS 1, mRS 6 |

| Inamasu et al. [17]/2002 | 36 | 53/f | WFNS 5, GCS 4, H&H V, bilaterally dilated pupils | CT scan, DSA | Yes | No | Rt | <25 cc | >10 mm | Rt ICA-Pcom | — | Craniotomy, hematoma evacuation, and clipping | Deceased (3 days after admission due to severe postoperative brain swelling), GOS 1, mRS 6 |

| Inamasu et al. [17]/2002 | 37 | 72/f | WFNS 5, GCS 4, H&H V | CT scan, | Yes | No | — | <25 cc | >10 mm | Lt ICA-Pcom (autopsy) | — | Infusions of manitol, burr hole | Deceased, GOS 1, mRS 6 |

| Inamasu et al. [17]/2002 | 38 | 53/m | WFNS 5, GCS 5, H&H V | CT scan | Yes | No | — | <25 cc | >10 mm | Unknown | — | Infusions of manitol, burr hole | Deceased, GOS 1, mRS 6 |

| Inamasu et al. [17]/2002 | 39 | 47/f | WFNS 5, GCS 4, H&H V | CT scan | Yes | No | — | <25 cc | >10 mm | Unknown | — | Infusions of manitol, burr hole | Deceased, GOS 1, mRS 6 |

| Inamasu et al. [17]/2002 | 40 | 70/f | WFNS 5, GCS 4, H&H V | CT scan | Yes | Yes | — | <25 cc | >10 mm | Unknown | — | No response to manitol infusion, conservative treatment | Deceased, GOS 1, mRS 6 |

| Inamasu et al. [17]/2002 | 41 | 81/f | WFNS 5, GCS 4, H&H V | CT scan | Yes | No | — | <25 cc | >10 mm | Unknown | — | No response to manitol infusion, conservative treatment | Deceased, GOS 1, mRS 6 |

| Inamasu et al. [17]/2002 | 42 | 55/m | WFNS 5, GCS 3, H&H V | CT scan | Yes | No | — | <25 cc | >10 mm | Unknown | — | No response to manitol infusion, conservative treatment | Deceased, GOS 1, mRS 6 |

| Inamasu et al. [17]/2002 | 43 | 49/m | WFNS 5, GCS 3, H&H V | CT scan | Yes | No | — | <25 cc | >10 mm | Unknown | — | No response to manitol infusion, conservative treatment | Deceased, GOS 1, mRS 6 |

| Gelabert-Gonzalez et al. [18]/2004 | 44 | 68/f | WFNS 5, GCS 4, fixed pupils | CT scan, DSA | Yes | No | Lt | — | — | Lt ICA-Pcom | — | Hematoma evacuation and immediate clipping (4 h) | Mild right-sided hemiparesis, GOS 4, mRS 2 |

| Gelabert-Gonzalez et al. [18]/2004 | 45 | 64/f | WFNS 4, GCS 9, dilation of the right pupil | CT scan, CTA | Yes | — | Rt | — | Marked | Lt ICA-Pcom | — | Hematoma evacuation and immediate clipping (28 h) | Full recovery, neurologically intact, GOS 5, mRS 1 |

| Gelabert-Gonzalez et al. [18]/2004 | 46 | 41/f | WFNS 5, GCS 4, right oculomotor paresis | CT scan, DSA | Yes | Yes | Lt | — | Marked | Lt ICA-Pcom | — | Hematoma evacuation and immediate clipping (5 h) | Deceased, GOS 1, mRS 6 |

| Gelabert-Gonzalez et al. [18]/2004 | 47 | 59/f | WFNS 5, GCS 6, bilaterally fixed pupils | CT scan, DSA | Yes | No | Rt | — | — | Rt ICA | 3 mm | Hematoma evacuation and immediate clipping (9 h) | Deceased, GOS 1, mRS 6 |

| Krishnaney et al. [19]/2004 | 48 | 42/f | WFNS 2, GCS 14 | CT scan, MRI, MRA, DSA | No | No | Bilateral | — | — | Acom | 10 mm | Craniotomy, hematoma evacuation and clipping, (6 days) | Uneventful recovery, no neurological deficits, GOS 5, mRS 1 |

| Kim et al. [20]/2005 | 49 | 72/f | WFNS 2, GCS 14 | CT scan, DSA | Yes | Yes | Rt | 6 mm | 8 mm | Lt distal ACA | — | Hematoma evacuation and immediate clipping (48 h) | Dysphasia, right hemiparesis, GOS 3, mRS 4 |

| Kim et al. [20]/2005 | 50 | 42/m | WFNS 5, GCS 3, bilaterally fixed pupils | CT scan, DSA | Yes | — | Lt | 6.5 mm | 10 mm | Lt ICA-Pcom | — | Hematoma evacuation and immediate clipping (3 h) | Mild left-sided arm paresis, GOS 4 mRS 3 |

| Marinelli et al. [21]/2005 | 51 | 62/f | WFNS 1, GCS 15, complete left third nerve palsy | CT scan, MRI, MRA, DSA | No | No | Lt | — | — | Lt ICA-Pcom | 10 mm | Endovascular embolization | Full recovery of left third nerve palsy, GOS 5, mRS 1 |

| Hori et al. [22]/2005 | 52 | 57/m | WFNS 2, GCS 13-14, incomplete right oculomotor palsy | CT scan, DSA | No | No | Rt | — | Moderate to marked | Rt MCA | 1.5 mm | Hematoma evacuation and immediate clipping | Full recovery, GOS 5, mRS 1 |

| Koerbel et al. [23]/2005 | 53 | 62/f | WFNS 4, GCS 10-11, rapid neurological deterioration | CT scan, DSA | No | No | Lt | — | Moderate to marked | Lt ICA-Pcom | 5 mm | Hematoma evacuation followed by coiling | Returned to normal lifestyle, GOS 5, mRS 1 |

| Westermaier et al. [4]/07 | 54 | 55/f | WFNS 5, GCS 6, anisocoria right | CT scan, DSA | Yes | Yes | Rt | — | — | Rt Acom | — | EVD coiling and hematoma evacuation (24 h) | No formal deficits, mobile for short distance, GOS 4, Barthel 70 |

| Westermaier et al. [4]/07 | 55 | 56/f | WFNS 5, GCS 3, MI, bilaterally fixed pupils, cardiopulmonary unstable | CT scan, DSA | Yes | Yes | Rt | — | — | Rt MCA | Large | Repeated infusions of manitol, hematoma evacuation, and immediate clipping (24 h) | Simple communication, left hemiparesis, permanent care, GOS 3, Barthel 20 |

| Westermaier et al. [4]/07 | 56 | 55/f | WFNS 5, GCS 3, dilation of the right pupil | CT scan, DSA | Yes | No | Rt | — | — | Rt ICA-Pcom | — | Immediate hematoma evacuation, EVD and delayed coiling (24 h) | Mild left hemiparesis, GOS 4, Barthel 70 |

| Westermaier et al. [4]/07 | 57 | 55/f | WFNS 5, GCS < 6, anisocoria right | CT scan, DSA | Yes | No | Rt | — | — | Rt Acom | — | Immediate hematoma evacuation, EVD, and delayed coiling (24 h) | Full recovery, return to work, GOS 5, mRS 1 |

| Westermaier et al. [4]/07 | 58 | 43/f | WFNS 5, bilaterally fixed and dilated pupils | CT scan | Yes | No | Lt | — | — | Lt ICA-Pcom | — | Hematoma evacuation followed by coiling | Rt hemiparesis using a wheelchair for longer distances, GOS 3, Barthel 70 |

| Westermaier et al. [4]/07 | 59 | 54/f | WFNS 5, GCS 3, dilation of the right pupil, cardiac instability | CT scan, DSA | Yes | — | Rt | — | — | Rt Acom | — | EVD, delayed coiling (24 h), hematoma evacuation three weeks later (burr hole) | Not able to walk, dependent on permanent care, GOS 3, Barthel 0 |

| Westermaier et al. [4]/07 | 60 | 42/f | WFNS 5, dilation of the right pupil | CT scan, DSA | Yes | — | Rt | — | — | Rt ICA-Pcom | — | EVD, hematoma evacuation, and immediate clipping | Returned to normal lifestyle, GOS 5, Barthel 100 |

| Westermaier et al. [4]/07 | 61 | 55/f | WFNS 5, bilaterally fixed pupils, cyanotic and hypoxic | CT scan | Yes | Yes | Rt | 5 mm | 4 mm | Rt MCA | 14 mm | No therapy as a result of prolonged hypoxia before admission | Deceased, GOS 1, mRS 6 |

| Gilad et al. [24]/2007 | 62 | 47/m | WFNS 1, GCS 15, partial left sixth cranial nerve palsy | CT scan, MRI, MRA, DSA | No | No | Tentorium midline | — | — | Intrasellar Acom | 13 mm | Coil embolization alone | Uneventful, no neurological deficits, GOS 5, mRS 1 |

| Suhara et al. [25]/2008 | 63 | 27/f | WFNS 4, GCS 8 | CT scan, DSA | No | No | Rt | — | — | Lt Pcal (ACA) | 7 mm | Craniectomy, immediate hematoma evacuation, and delayed clipping (5 days) | Uneventful recovery, no neurological deficits, GOS 5, mRS 1 |

| Nishikawa et al. [26]/2009 | 64 | 45/m | WFNS 5, GCS 5, dilated slowly reacting pupils | CT scan, MRI, MRA | No | Yes | Bilateral | — | Moderate to marked | Lt ICA | — | Emergency hematoma evacuation, and clipping | Deceased (cerebral herniation 6 days after admission), GOS 1, mRS 6 |

| Kocak et al. [27]/09 | 65 | 68/f | WFNS 5, GCS 6 | CT scan, DSA | Yes | No | — | — | Rt ICA bifurcation | — | Patient died during resuscitation | Deceased, GOS 1, mRS 6 | |

| Kocak et al. [27]/09 | 66 | 53/m | WFNS 2, GCS 14 | CT scan, DSA | Yes | No | — | — | Lt Pcom | — | Craniotomy, hematoma evacuation, and immediate clipping | Good recovery, GOS 5, mRs 1 | |

| Kocak et al. [27]/09 | 67 | 48/f | WFNS 3, GCS 10 | CT scan, DSA (after hematoma evacuation) | Yes | No | — | Moderate to marked | Rt Pcom | — | Craniotomy and immediate hematoma evacuation, delayed clipping (6 days) | Severe disability, GOS 3, mRS 5 | |

| Kocak et al. [27]/09 | 68 | 63/f | WFNS 1, GCS 15 | CT scan, DSA | Yes | No | — | — | Lt MCA | — | Craniotomy, hematoma evacuation, and immediate clipping | Good recovery, GOS 5, mRs 1 | |

| Kocak et al. [27]/09 | 69 | 51/f | WFNS 2, GCS 14 | CT scan, DSA | Yes | No | — | — | Acom | — | Craniotomy, SDH evacuation, clipping | Good recovery, GOS 5, mRs 1 | |

| Kocak et al. [27]/09 | 70 | 72/f | WFNS 4, GCS 8 | CT scan, DSA | Yes | Yes | — | Moderate to marked | Rt MCA | — | Craniotomy, hematoma evacuation (aSDH + ICH) and immediate clipping | Deceased, GOS 1, mRS 6 | |

| Kocak et al. [27]/09 | 71 | 56/f | WFNS 4, GCS 7 | CT scan, DSA | Yes | Yes | — | Moderate to marked | Rt MCA | — | Craniotomy, hematoma evacuation (aSDH + ICH), and immediate clipping (6 h) | Deceased, GOS 1, mRS 6 | |

| Kocak et al. [27]/09 | 72 | 67/m | WFNS 5, GCS 5 | CT scan, DSA (after hematoma evacuation) | Yes | No | — | Moderate to marked | Rt Pcom | — | Craniotomy and immediate hematoma evacuation, delayed clipping (8 days) | Severe disability, GOS 3, mRS 5 | |

| Kocak et al. [27]/09 | 73 | 47/f | WFNS 1, GCS 15 | CT scan, CTA, DSA | No | No | — | — | Acom | — | Craniotomy, hematoma evacuation, and immediate clipping | Good recovery, GOS 5, mRs 1 | |

| Kocak et al. [27]/09 | 74 | 57/f | WFNS 3, GCS 13 | CT scan, CTA, DSA | Yes | No | — | — | Lt Pcom | — | Craniotomy, hematoma evacuation, and immediate clipping | Good recovery, GOS 5, mRs 1 | |

| Kocak et al. [27]/09 | 75 | 46/f | WFNS 4, GCS 12 | CT scan, CTA, DSA | Yes | No | — | — | Rt Pcom | — | Craniotomy, hematoma evacuation, and immediate clipping | Severe disability, GOS 3, mRS 5 | |

| Marbacher et al. [2]/10 | 76 | 44/f | WFNS 5, GCS 3, bilaterally fixed pupils | CT scan, DSA | Yes | No | Rt | 15 mm | 10 mm | Rt Pcal (ACA) | 5 mm | Craniectomy, hematoma evacuation (4 h), and delayed clipping | Full recovery, mild cognitive deficits, GOS 5, mRS 1 |

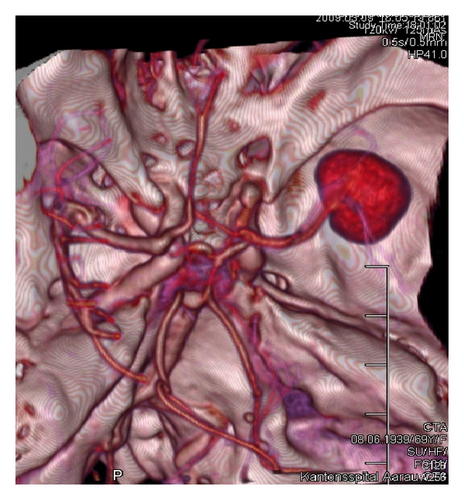

| Marbacher et al. [2]/10 | 77 | 50/f | WFNS 3, GCS 13, mild left-sided hemiparesis | CT scan, CTA | Yes | Yes | Rt | 9 mm | 23 mm | Rt MCA | 11 mm | Craniectomy, hematoma evacuation (12 h), and delayed coiling | Mild left-sided arm paresis, GOS 4, mRS 2 |

| Marbacher et al. [2]/10 | 78 | 39/m | WFNS 5, GCS 4, bilaterally fixed pupils | CT scan, CTA | Yes | No | Rt | 10 mm | 14 mm | Rt ICA-Pcom | 5 mm | EVD, craniectomy, hematoma evacuation, and immediate clipping (18 h) | Residual left-sided hemiparesis, GOS 4, mRS 2 |

| Marbacher et al. [2]/10 | 79 | 58/f | WFNS 5, GCS 5, dilation of the right pupil | CT scan, CTA | Yes | Yes | Rt | 5 mm | 4 mm | Rt MCA | 14 mm | Craniectomy, hematoma evacuation, and immediate clipping (3 h) | Full recovery, mild cognitive deficits, GOS 5, mRS 1 |

| Marbacher et al. [2]/10 | 80 | 45/f | WFNS 5, GCS 4, dilation of the right pupil | CT scan, DSA | Yes | No | Rt | 20 mm | 18 mm | Rt ICA-Pcom | 7 mm | Craniectomy, hematoma evacuation, and immediate clipping (2 h) | Gait ataxia, GOS 4, mRS 3 |

| Marbacher et al. [2]/10 | 81 | 68/f | WFNS 1, GCS 15, right oculomotor paresis | CT scan, CTA | Yes | No | Rt | 10 mm | 6 mm | Rt Distal ICA-Pcom | 2 mm | Craniotomy, hematoma evacuation, and immediate clipping (6 h) | Full recovery, no symptoms at all, GOS 5, mRS 0 |

| Marbacher et al. [2]/10 | 82 | 27/f | WFNS 5, GCS 3, bilaterally fixed mydriasis, unstable cardiopulmonary condition | CT scan, DSA | Yes | No | Rt | 10 mm | 7 mm | Rt Pcal (ACA) | 12 mm | Craniectomy, hematoma evacuation (1 h) | Deceased, GOS 1, mRS 6 |

- *Summary (characteristics) of 82 cases from 20 clinical case series or case reports of aneurysmal acute subdural hematomas. Abbreviations: SAH = subarachnoid hemorrhage; ICH = intracerebral hemorrhage; aSDH = acute subdural hematoma; MLS = midline shift; mm = millimeter; f = female; m = male; WFNS = World Federation of Neurological Surgeons; GCS = Glasgow Coma Scale; CT = computed tomography; Rt = right; Lt = left; mRS = modified Rankin Score; GOS = Glasgow Outcome Scale; FU = followup; NOS = not otherwise specified; Barthel = Barthel Index; DSA = digital subtraction angiography; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; MRA = magnetic resonance angiography; MCA = middle cerebral artery; CTA = CT angiography; ICA = internal carotid artery; Pcom = posterior communicating artery; Acom = anterior communicating artery; ACA = anterior cerebral artery; Pcal = pericallosal artery; EVD = external ventricular drainage; MI = myocardial infarction.

3.1. Initial Clinical Findings

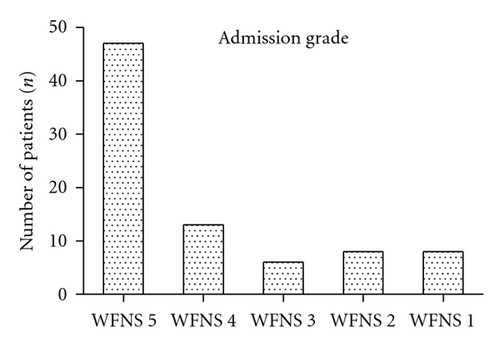

Most of the patients were admitted with the worst initial clinical SAH grades and with signs of uncal herniation. The distribution according to the WFNS was grade 5 (n = 46, 57.3%), grade 4 (n = 14, 17.1%), grade 3 (n = 6, 7.3%), grade 2 (n = 8, 9.8%), and grade 1 (n = 8, 9.8%). At admission, signs of uncal herniation, major focal neurological deficits, and minor focal neurological deficits were present in 35 (42.7%), eight (9.8%), and six (7.3%) patients, respectively. Fourteen (17.1%) patients presented in an unstable cardiopulmonary condition (e.g., ventricular arrhythmia, acute heart failure, and sudden pulmonary edema) at the time of admission. Four (4.9%) patients died during resuscitation. One (1.2%) patient was reported to have had prolonged hypoxia.

3.2. Diagnostic Approaches and Radiological Findings

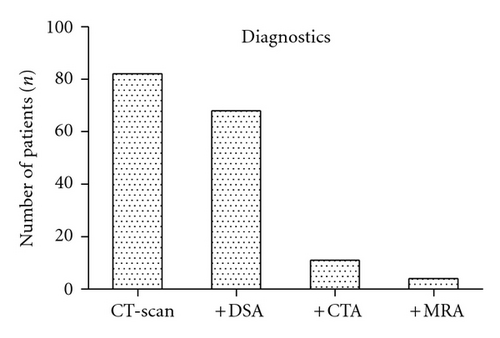

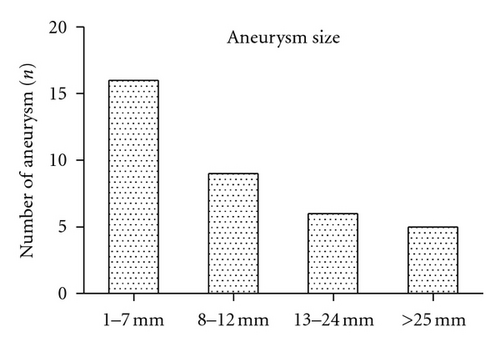

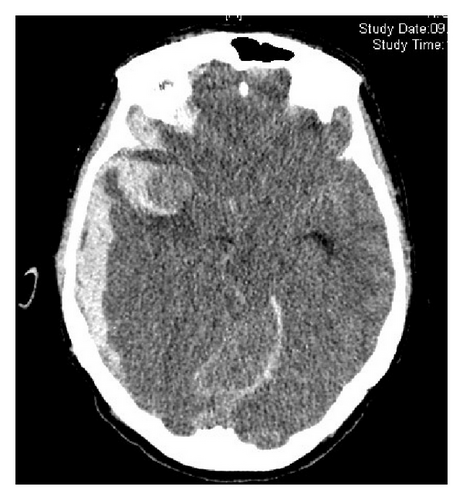

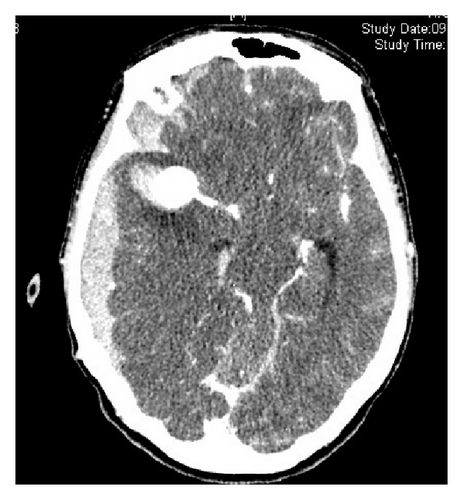

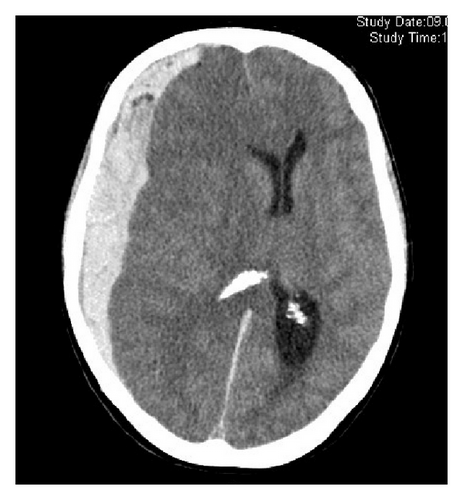

For all patients, the first radiological assessment was a CT scan (n = 82, 100%). 68 (82.9%) patients underwent additional DSA, and 11 (13.4%) underwent additional CTA (Figure 2). Four (4.9%) patients underwent MRA prior to surgery. SAH was detected on initial CT scan in 68 (82.9%) patients. There were 13 (15.9%) cases of pure aSDH without associated SAH. 28 (34.1%) patients presented with additional ICH. In 24 (29.3%) patients, the size of the aSDH was reported (mean ± SD: 9.6 ± 3.5, range: 5–20 mm). A total of 30 (36.6%) patients were reported as presenting with midline shift associated with aSDH (mean ± SD: 9.1 ± 4.0, range: 4–23 mm). All but six cases (7.3%) of aSDH were documented ipsilateral to the side of the aneurysm. Two cases presented with bilateral aSDH. Aneurysm size was reported in 37 (45.1%) patients (mean ± SD: 11.4 ± 8.1, range: 1.5–30 mm).

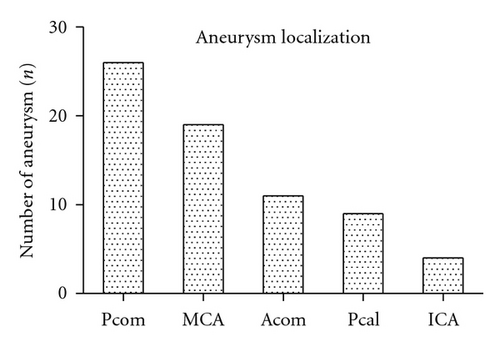

3.3. Aneurysm Localization

In most of the cases, the aneurysm was located in the posterior communicating artery (Pcom) (n = 39, 46.6%). The rest of the aneurysms were located in the middle cerebral artery (MCA) (n = 20, 23.2%), the anterior communicating artery (Acom) (n = 11, 13.4%), the pericallosal artery (Pcal) (n = 8, 9.8%), or the internal carotid artery ICA (n = 4, 4.9%).

3.4. Treatment Strategies

The treatment strategies included urgent hematoma evacuation (n = 59, 72%), surgical aneurysm obliteration in the same procedure as urgent hematoma evacuation (n = 41, 50%), delayed clipping (n = 10, 12.2%), and delayed coiling (n = 6, 7.3%). Eighteen patients (22%) died during resuscitation or did not meet the criteria for undergoing any of the invasive procedures due to cardiopulmonary instability. A total of six (7.3%) patients underwent external ventricular drainage, and ten (12.2%) patients were treated with hyperosmolar therapy.

3.5. Outcome

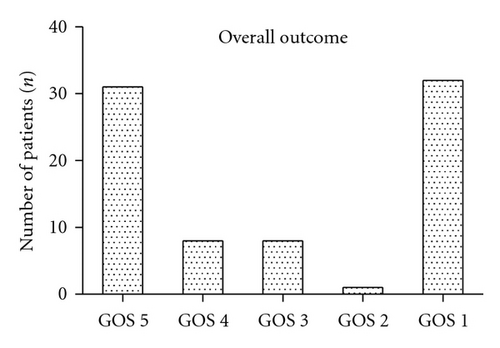

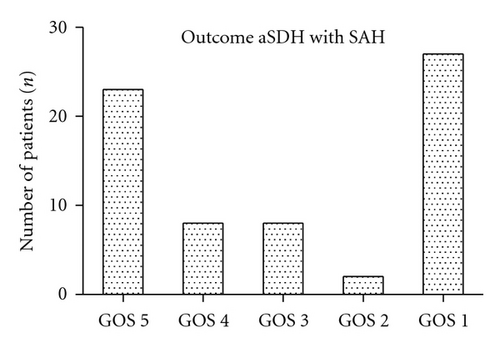

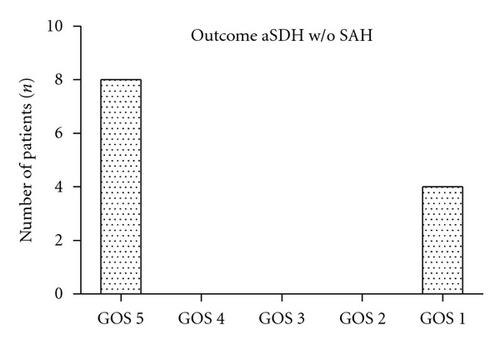

Half of the patients were reported to have favorable outcomes (GOS 5 and GOS 4, n = 39, 47.6%). Poor outcome (GOS 3 and GOS 2) was reported in nine (11%) patients. 32 patients (26.6%) had fatal outcomes (GOS 1). Overall distribution according to the GOS was GOS 5 (n = 31, 37.8%), GOS 4 (n = 8, 9.8%), GOS 3 (n = 8, 9.8%), GOS 2 (n = 1, 1.2%), and GOS 1 (n = 32, 39%). In 19 (23.2%) out of 32 patients with fatal outcome (GOS 1), the critical status at admission did not allow any surgical or endovascular intervention. Four (4.9%) patients died during resuscitation, two (2.4%) patients died immediately after diagnosis, and one (1.2%) patient received no further therapy as a result of prolonged hypoxia before admission. Most of the 63 patients who met the criteria for invasive treatment achieved good outcomes (GOS 5 and GOS 4, n = 39, 69.9%). The distribution of these patients by treatment outcome according to the GOS was GOS 5 (n = 31, 49.2%), GOS 4 (n = 8, 12.7%), GOS 3 (n = 8, 12.7%), GOS 2 (n = 1, 1.6%), and GOS 1 (n = 13, 20.6%). Patients who suffered aneurysmal aSDH without SAH demonstrated better outcomes (GOS 5, n = 9, 69.2%; GOS 1, n = 5, 38.5%) than patients who presented with aneurysmal aSDH and SAH (GOS 5, n = 22, 31.4%; GOS 4, n = 8, 11.4%; GOS 3, n = 8, 11.4%; GOS 2, n = 1, 1.4%; GOS 1, n = 27, 38.6%).

3.6. Outcome Stratified by Therapeutic Strategies (Table 3)

| Patients presenting with rapidly deteriorating neurological condition | Patients presenting without rapidly deteriorating neurological condition | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urgent intervention (<24 h) | Delayed intervention (>24 h) | Urgent intervention (<24 h) | Delayed intervention (>24 h) | ||||

| Outcome | n (%) | Outcome | n (%) | Outcome | n (%) | Outcome | n (%) |

| GOS 5 + 4 | 23 (64%) | GOS 5 + 4 | 6 (25%) | GOS 5 + 4 | 10 (100%) | GOS 5 + 4 | 5 (100%) |

| GOS 3 + 2 | 5 (14%) | GOS 3 + 2 | 2 (8%) | GOS 3 + 2 | 0 (0%) | GOS 3 + 2 | 0 (0%) |

| GOS 1 | 8 (22%) | GOS 1 | 16 (67%) | GOS 1 | 0 (0%) | GOS 1 | 0 (0%) |

- *Abbreviations: GOS = Glasgow Outcome Scale.

All patients presenting in good clinical condition without rapid neurological deterioration (n = 15) demonstrated good outcomes (GOS 5 and GOS 4). These outcomes were favorable irrespective of whether hematoma evacuation and aneurysm obliteration were immediate (n = 10) or delayed (n = 5). However, patients with rapidly deteriorating levels of consciousness (including signs of brain herniation) and urgent (<24 h) intervention had a higher likelihood of good outcomes (GOS 5 and GOS 4) than patients with rapid deterioration who had undergone delayed (24 h) treatment (64% versus 25%).

4. Discussion

This meta-analysis of 82 reported cases presenting with aneurysmal aSDH and rapid neurological deterioration revealed that urgent surgical decompression and immediate occlusion of the aneurysm seem to be an acceptable treatment strategy in order to achieve better outcome (GOS 5 and GOS 4 = 64%). Good outcomes are found in patients maintaining stable neurological condition irrespective of whether intervention was immediate or delayed (GOS 5 = 100%). Patients with pure aSDH due to a ruptured aneurysm demonstrated better outcomes than patients who suffered aneurysmal aSDH associated with SAH. Patients in unstable cardiopulmonary condition, with unstable blood pressure and serious ventricular arrhythmias, have the highest risk of unfavorable outcomes. All patients who did not meet the criteria for invasive treatment had fatal outcomes.

Poor clinical presentation per se is not associated with worse outcome. However, the combination of marginal cardiac output and reduced cerebral perfusion and cerebral blood flow due to the mass effect [31] during the acute phase of SAH [32] is likely to result in poor final outcome. Patients presenting in such condition do not meet the criteria for urgent hematoma evacuation, which additionally worsens the likelihood of favorable outcome (GOS 5 and GOS 4 = 25%). Patients in stable hemodynamic condition are suitable for rapid surgical decompression and maximal medical treatment and have a higher chance of recovering in good neurological condition (GOS 5 and GOS 4 = 64%) despite severe SAH and poor initial GCS admission scores. Two-thirds of all patients with either poor grade SAH or traumatic aSDH usually do not survive, and functional outcome is rare [33–35]. The good recovery of patients with aneurysmal aSDH might be explained by the space-occupying effect of the hematoma, which mimics a worse clinical situation and does not reflect vital brain destruction.

Pure aSDH due to ruptured intracranial aneurysm is extremely rare. Only 20 cases have been reported so far, including 14 cases during the last two decades [16]. In most cases of aneurysmal aSDH, the history will distinguish a traumatic from a spontaneous cause [1]. However, the absence of hematomas and subarachnoid blood collections related to common aneurysm sites can impede the diagnosis. The finding that pure aneurysmal aSDH results in better outcome than aSDH with SAH may be explained by the fact that these patients less frequently have complications (delayed cerebral vasospasm and hydrocephalus).

Due to the rarity of the disease, no guidelines have been established. In most reports, patients have bad clinical features on admission, often presenting in a comatose state with pupillary abnormalities. Fast decision making is mandatory. Determining a differential diagnosis, as well as treatment modalities, can be complicated by the rapid clinical course and the mixture of symptoms due to the ruptured aneurysm or mass effect of the hematoma.

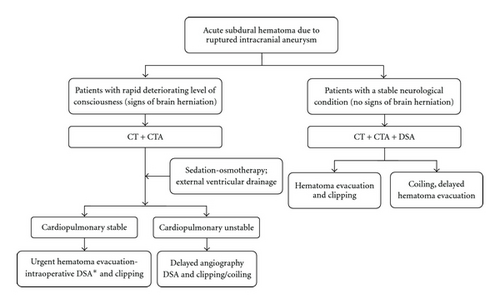

To address the lack of guidelines, we developed a flowchart for treatment of patients with aSDH. However, the evidence for the proposed treatment flowchart comes from case series and case reports with relatively small sample sizes. Therefore, the estimation of effects is imprecise, and clinical recommendations included in the management protocol are weak [36, 37].

In patients who are in good neurological condition at the time of admission, management may proceed in a standard manner (Figure 3, left side of the flowchart). After initial CT and CTA examination, DSA is the diagnostic modality of choice to verify the angioarchitecture of the aneurysm. If the aneurysm is suitable for endovascular obliteration and the aSDH remains clinically insignificant, the aneurysm can be occluded during the same procedure [4]. If a decision is made to occlude the aneurysm surgically, DSA provides relevant anatomical information and guidance in determining a clipping strategy and surgical approach.

For the management of patients who are in a coma or whose level of consciousness is deteriorating rapidly, the choice of initial diagnostics is more demanding, and management decisions become difficult (Figure 3, right side of the flowchart). The aSDH may be the major determinant of neurological grade, and prompt hematoma evacuation may be life saving. At the minimum, neuroradiological investigations should consist of an emergency CT and CTA to visualize potential bleeding sources. Emergency treatment modalities such as maximal sedation, osmotherapy, and external ventricular drainage to reverse signs of brain herniation should be performed as quickly as possible. In these cases, the emergency situation forces the neurosurgeon to postpone DSA.

Intraoperative DSA would allow safe and complete aneurysm occlusion to be carried out at the same time as urgent hematoma evacuation [38, 39]. Patients would be spared a second procedure. However, Westermaier et al. [4] recently presented four patients who underwent separate delayed endovascular coiling after decompression and hematoma evacuation. Despite good neurological recovery in three of these four patients, subjecting patients to two separate procedures rather than clipping at the same time as hematoma removal remains controversial. Patients who present in unstable cardiopulmonary conditions cannot be operated on immediately. It seems that this subgroup of patients is exceptionally at risk of poor outcome. Withholding aggressive therapy in poor-grade patients in order to prevent vegetative survival is highly controversial and cannot be recommended.

5. Conclusion

Due to the rarity of aneurysmal aSDH, it remains difficult to define a comprehensive management protocol. In patients with poor neurological grade at admission and rapidly deteriorating levels of consciousness, urgent surgical decompression and immediate aneurysm obliteration result in favorable outcome (GOS 5 and GOS 4; 64%). Delay of immediate treatment in patients with rapidly deteriorating neurological conditions decreases the likelihood of a favorable outcome (GOS 5 and GOS 4; 25%). Good outcomes are observed in patients maintaining stable neurological condition irrespective of whether the intervention was immediate or delayed (GOS 5; 100%). Overall outcome of patients who suffered aneurysmal aSDH without SAH proved to be better (GOS 5, 69.2%) than the outcome of patients who presented with aneurysmal aSDH and SAH (GOS 5; 31.4%).

Conflict of Interests

The authors are solely responsible for the design and conduct of the presented study and report no conflict of interests. No funds were or will be received for this study.