Asymptotic Behavior of the Likelihood Function of Covariance Matrices of Spatial Gaussian Processes

Abstract

The covariance structure of spatial Gaussian predictors (aka Kriging predictors) is generally modeled by parameterized covariance functions; the associated hyperparameters in turn are estimated via the method of maximum likelihood. In this work, the asymptotic behavior of the maximum likelihood of spatial Gaussian predictor models as a function of its hyperparameters is investigated theoretically. Asymptotic sandwich bounds for the maximum likelihood function in terms of the condition number of the associated covariance matrix are established. As a consequence, the main result is obtained: optimally trained nondegenerate spatial Gaussian processes cannot feature arbitrary ill-conditioned correlation matrices. The implication of this theorem on Kriging hyperparameter optimization is exposed. A nonartificial example is presented, where maximum likelihood-based Kriging model training is necessarily bound to fail.

1. Introduction

Spatial Gaussian processing, also known as best linear unbiased prediction, refers to a statistical data interpolation method, which is nowadays applied in a wide range of scientific fields, including computer experiments in modern engineering context; see, for example, [1–5]. As a powerful tool for geostatistics, it has been pioneered by Krige in 1951 [6], and to pay tribute to his achievements, the method is also termed Kriging; see [7, 8] for geostatistical background.

In practical applications, the data′s covariance structure is modeled through covariance functions depending on the so-called hyperparameters. These, in turn, are estimated by optimizing the corresponding maximum likelihood function. It has been demonstrated by many authors that the accuracy of Kriging predictors relies both heavily on hyperparameter-based model training and, from the numerical point of view, on the condition number of the associated Kriging correlation matrix. In this regard, we relate to the following, nonexhaustive selection of papers: Warnes and Ripley [9] and Mardia and Watkins [10] present numerical examples of difficult-to-optimize covariance model functions. Ababou et al. [11] show that likelihood-optimized hyperparameters may correspond to ill-conditioned correlation matrices. Diamond and Armstrong [12] prove error estimates under perturbation of covariance models, demonstrating a strong dependence on the correlation matrix′ condition number. In the same setting, Posa [13] investigates numerically the behavior of this precise condition number for different covariance models and varying hyperparameters. An extensive experimental study of the condition number as a function of all parameters in the Kriging exercise is provided by Davis and Morris [14]. Schöttle and Werner [15] propose Kriging model training under suitable conditioning constraints. Related is the work of Ying [16] and Zhang and Zimmerman [17], who prove asymptotic results on limiting distributions of maximum likelihood estimators when the number of sample points approaches infinity. Radial basis function interpolant limits are investigated in [18]. Modern textbooks covering recent results are [19, 20].

In this paper, the connection between hyper-parameter optimization and the condition number of the correlation matrix is investigated from a theoretical point of view. The setting is as follows. All sample data is considered as fixed. An arbitrary feasible covariance model function is chosen for good, so that only the covariance models′ hyperparameters are allowed to vary in order to adjust the model likelihood. This is exactly the situation as it occurs in the context of computer experiments, where, based on a fixed set of sample data, predictor models have to be trained numerically. We prove that, under weak conditions, the limit values of the quantities in the model training exercise exist. Subsequently, by establishing asymptotic sandwich bounds on the model likelihood based on the condition number of the associated correlation matrix, it is shown that ill-conditioning eventually also decreases the model likelihood. This result implies a strategy for choosing good starting solutions for hyperparameter-based model training. We emphasize that all covariance models applied in the papers briefly reviewed above subordinate to the theoretical setting of this work.

The paper is organized as follows. In the next section, a short review of the basic theory behind Kriging is given. The main theorem is stated and proved in Section 3. In Section 4, an example of a Kriging data set is presented, which illustrates the limitations of classical model training.

2. Kriging in a Nutshell

- (1)

constant regression (ordinary Kriging): p = 0, f : ℝd → ℝ, x ↦ 1, f(x)β = β ∈ ℝ,

- (2)

linear regression (universal Kriging): p = d, f : ℝd → ℝd+1, x ↦ (1, x1, …, xd), f(x)β = β0 + β1x1 + ⋯+βdxd ∈ ℝ,

and higher-order polynomials.

Convention 1 Large distance weight values correspond to weak spatial correlation, and small distance weight values correspond to strong spatial correlation. More precisely, we assume that feasible spatial correlation functions are always parameterized such that

3. Asymptotic Behavior of the Maximum Likelihood Function—Why Kriging Model Training Is Tricky: Part I

Theorem 3.1. Let x1, …, xn ∈ ℝd, Y : = (y(x1), …, y(xn)) ∈ ℝn be a data set of sampled sites and responses. Let R(θ) be the associated spatial correlation matrix, and let Σ(θ) be the vector of errors with respect to the chosen regression model. Furthermore, let cond(R(θ)) be the condition number of R(θ). Suppose that the following conditions hold true:

- (1)

the eigenvalues λi(θ) of R(θ) are mutually distinct for small 0 < ∥θ∥≤ɛ, θ ∈ ℝd,

- (2)

the derivatives of the eigenvalues do not vanish in the limit: for all j = 2, …, n,

- (3)

Σ(0) ∉ span {1}, Σ(0) ∉ 1⊥.

Remark 3.2. (1) The conditions given in the above theorem cannot be proven to hold true in general, since they depend on the data set in question. However, they hold true for nondegenerate data set. In Appendix A, a relationship between condition 2 and the regularity of R′(0) is established, giving strong support that condition 2 is generally valid. Concerning the third condition, it will be shown in Lemma 3.4, that the limit Σ(0) exists, given conditions 1 and 2. Note that the set span {1} ∪ 1⊥ is of Lebesgue measure zero in ℝn. In all practical applications known to the author, these conditions were fulfilled.

(2) It holds that lim ∥θ∥→∞(R(θ)) i,j = I ∈ ℝn×n. Hence, the likelihood function approaches a constant limit for ∥θ∥→∞ and lim ∥θ∥→∞cond(R(θ)) = 1. The corresponding predictor behavior is investigated in Section 4.

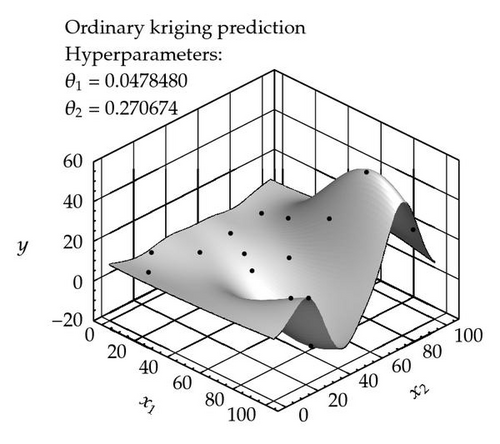

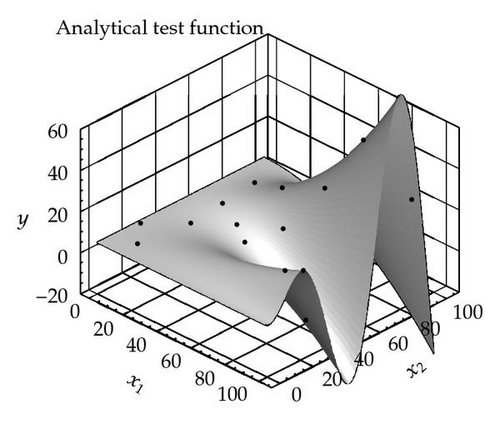

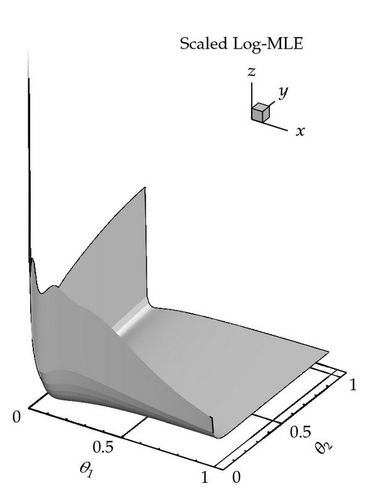

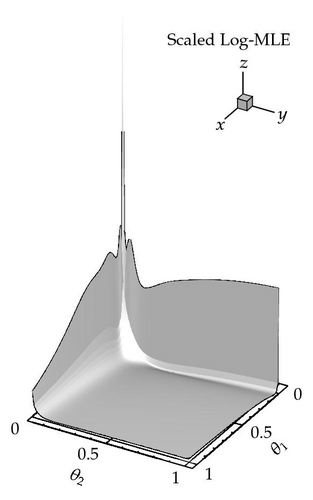

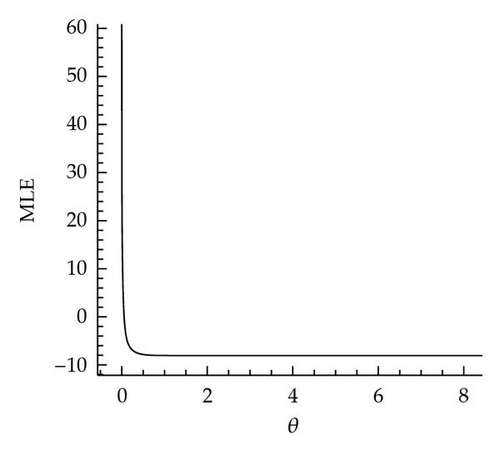

(3) Even though Theorem 3.1 shows that the model likelihood becomes arbitrarily bad for hyperparameters ∥θ∥→0, the optimum might lie very close to the blowup region of the condition number, leading to still quite ill-conditioned covariance matrices [11]. This fact as well as the general behavior of the likelihood function as predicted by Theorem 3.1 is illustrated in Figure 1.

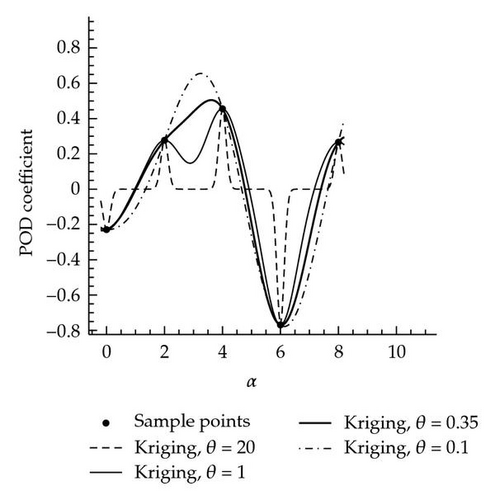

(4) Figure 2(b), provides an additional illustration of Theorem 3.1.

(5) Theorem 3.1 offers a strategy for choosing starting solutions for the optimization problem (2.16): take each θk, k ∈ 1, …, d as small as possible such that the corresponding correlation matrix is still (numerically) positive definite.

(6) A related investigation of interpolant limits has been performed in [18] but for standard radial basis functions.

In order to support readability, we divide the proof of Theorem 3.1 into smaller units, organized as follows. As a starting point, we establish two auxiliary lemmata on the existence of limits of eigenvalue quotients and of errors vectors. Subsequently, the proof of the main theorem is conducted relying on the lemmata.

Lemma 3.3. In the setting of Theorem 3.1, let λi(θ), i = 1, …, n be the eigenvalues of R(θ), ordered by size. Then,

Proof. Because of (2.13), it holds that (R(0)) i,j = 11T ∈ ℝn×n for every admissible spatial correlation function. Since (11T)1 = n1 ∈ ℝn and (11T)W = 0 for all W ∈ 1⊥ ⊂ ℝn, the limit eigenvalues of the correlation matrix ordered by size are given by λ1(0) = n > 0 = λ2(0) = ⋯ = λn(0).

Under the present conditions, the eigenvalues λi are differentiable with respect to θ. Hence, it is sufficient to proof the lemma for ℝ∋τ ↦ θ(τ) = τ1 ∈ ℝd and τ → 0. Now, condition 2 and L′Hospital′s rule imply the result.

Lemma 3.4. In the setting of Theorem 3.1, let Σ(θ) be defined by (2.18) and (2.19). Then,

Proof. We prove Lemma 3.4 by showing that lim ∥θ∥→0β(θ) exists.

Remember that β = (β0, …, βp) T ∈ ℝp+1, with p ∈ ℕ0 depending on the chosen regression model. As in the above lemma, we can restrict the considerations to the direction τ ↦ θ(τ) = τ1.

Let λi(θ), i = 1, …, n be the eigenvalues of R(θ) ordered by size with corresponding eigenvector matrix Q(θ) = (X1, …, Xn)(θ) such that Q(θ)R(θ)QT(θ) = Λ(θ) = diag (λ1, …, λn). For brevity, define Xi(τ): = Xi(θ(τ)) = Xi(τ1) and so forth.

It holds that ; see Lemma 3.3. Hence, 〈1, Xj(τ)〉→0 for τ → 0 and j = 2, …, n. In the present setting, the derivatives of eigenvalues and (normalized) eigenvectors exist and can be extended to 0; see, for example, [22]. By another application of L′Hospital′s rule,

Writing columnwise (F0, F1, …, Fp): = F, a direct computation shows

Remark 3.5. Actually, one cannot prove for (LFTQΛ−1) to be regular in general, since this matrix depends on the chosen sample locations. It might be possible to artificially choose samples such that, for example, F has not full rank. Yet if so, the whole Kriging exercise cannot be performed, since (2.19) is not well defined in this case. For constant regression, that is, F = 1, this is impossible. Note that F is independent of θ.

Now, let us prove Theorem 3.1 using notation as introduced above.

Proof. As shown in the proof of Lemma 3.3

If necessary, renumber such that λmax = λ1 ≥ ⋯≥λn = λmin . Let W(θ) = (W1(θ), …, Wn(θ)): = Q(θ)Σ(θ). By Lemma 3.4, W(0): = Q(0) TΣ(0) exists. Condition 3 insures that W1(0) ≠ 0.

Case 1. Suppose that Wi(0) ≠ 0 for all i = 1, …, n.

By continuity, Wi(θ) ≠ 0 for 0 ≤ ∥θ∥≤ɛ and ɛ > 0 small enough. Since {θ ∈ ℝd, 0 ≤ ∥θ∥≤ɛ} is a compact set,

Case 2. Suppose that Case 1 does not hold true.

From Σ(0) ∉ span {1}, it follows that

Define

By Lemma 3.3,

4. Why Kriging Model Training Is Tricky: Part II

The following simple observation illustrates Kriging predictor behavior for large-distance weights θ. Notation is to be understood as introduced in Section 3.

Observation 1. Suppose that sample locations {x1, …, xn} ⊂ ℝd and responses yi = y(xi) ∈ ℝ, i = 1, …, n are given. Let be the corresponding Kriging predictor according to (2.10). Then, for ℝd∋x ∉ {x1, …, xn} and distance weights ∥θ∥→∞, it holds that

Put in simple words: if too large distance weights are chosen, then the resulting predictor function has the shape of the regression model, x ↦ f(x)β, with peaks at the sample sites, compare Figure 2, dashed curve.

Proof. According to (2.10) it holds that

Remark 4.1. The same predictor behavior arises at locations far away from the sampled sites, that is, for dist (x, {x1, …, xn}) → ∞. This has to be considered, when extrapolating beyond the sample data set.

Figure 2 shows an example data set for which the Kriging maximum likelihood function is constant over a large range of θ values. This example was not constructed artificially but occured in the author′s daily work of computing approximate fluid flow solutions based on proper orthogonal decomposition (POD) followed by coefficient interpolation as described in [23, 24].

The sample data set is given in Table 1. The Kriging estimator given by the dashed line shows a behavior as predicted by Observation 1. Note that from the model training point of view, all distance weights θ > 1 are equally likely, yet lead to quite different predictor functions. Since the ML features no local minimum, classical hyperparameter estimation is impossible.

| x = α: | 0.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 6.0 | 8.0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| y(x): | −0.229334 | 0.277018 | 0.455534 | −0.769558 | 0.26634 |

Nomenclature

-

- d ∈ ℕ:

-

- Dimension of parameter space

-

- n ∈ ℕ:

-

- (Fixed) number of sample points

-

- xi ∈ ℝd:

-

- ith sample location

-

- yi ∈ ℝ:

-

- Sample value at sample location xi

-

- I ∈ ℝn×n:

-

- Unit matrix

-

- 1 : = (1, …, 1) T ∈ ℝn:

-

- Vector with all entries equal to 1

-

- :

-

- ith standard basis vector

-

- V⊥ ⊂ ℝn:

-

- Subspace of all vectors orthogonal to V ∈ ℝn

-

- R ∈ ℝn×n:

-

- Correlation matrix

-

- C ∈ ℝn×n:

-

- Covariance matrix

-

- cond(R):

-

- Condition number of R ∈ ℝn×n

-

- 〈·, ·〉:

-

- Euclidean scalar product

-

- e = exp (1):

-

- Euler’s number

-

- p + 1 ∈ ℕ:

-

- Dimension of regression model

-

- β ∈ ℝp+1:

-

- Vector of regression coefficients

-

- f : ℝd → ℝp+1:

-

- Regression model

-

- ϵ : ℝd → ℝ:

-

- Random error function

-

- E[·]:

-

- Expectation value

-

- :

-

- Standard deviation

-

- θ ∈ ℝd:

-

- Distance weights vector, model hyperparameters.

Acknowledgments

This research was partly sponsored by the European Regional Development Fund and Economic Development Fund of the Federal German State of Lower Saxony Contract/Grant no. W3-80026826.

Appendices

A. On the Validity of Condition 2 in Theorem 3.1

The next lemma strongly indicates that the second condition in the main Theorem 3.1 is given in nondegenerate cases.

Lemma A.1. Let ℝd∋θ ↦ R(θ) ∈ ℝn×n be the correlation matrix function corresponding to a given set of Kriging data and a fixed spatial correlation model.

Let λi(θ), i = 1, …, n be the eigenvalues of R ordered by size with corresponding eigenvector matrix Q = (X1, …, Xn), and define θ : ℝ → ℝd, τ ↦ θ(τ): = τ1. Suppose that the eigenvalues are mutually distinct for τ > 0 close to zero.

Denote the directional derivative in the direction 1 with respect to τ by a prime ′, that is, (d/dτ)R(τ1) = R′(τ) and so forth. Then, it holds that

Proof. For every admissible spatial spatial correlation function r(θ, ·, ·) of the form (2.11) and x ≠ z ∈ ℝd, it holds that

It holds that (11T)1 = n1 ∈ ℝn and (11T)W = 0 for all W ∈ 1⊥ ⊂ ℝn; therefore, the limits of the eigenvalues of the correlation matrix ordered by size are given by λ1(0) = n > λ2(0) = ⋯ = λn(0) = 0. The assumption, that no multiple eigenvalues occur, ensures that the eigenvalues λi and corresponding (normalized, oriented) eigenvectors Xi are differentiable with respect to τ. Let Q(τ) = (X1(τ), …, Xn(τ)) ∈ ℝn×n be the (orthogonal) matrix of eigenvectors, such that

Hence,

Let us assume, that there exist two indices j0, k0, j0 ≠ k0 such that .

Let . Then,

If W = 0, replace W by and repeat the above argument.

For most correlation models, the derivative R′(0) can be computed explicitly.

B. Test Setting Corresponding to Figure 1

The Kriging predictor function displayed in this figure has been constructed based on the fifteen (randomly chosen) sample points shown in Table 2.

| Location | x1 | x2 | y(x1, x2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 84.0188 | 39.4383 | −15.0146 |

| 2 | 78.3099 | 79.844 | 53.5481 |

| 3 | 91.1647 | 19.7551 | 20.0921 |

| 4 | 33.5223 | 76.823 | 13.506 |

| 5 | 27.7775 | 55.397 | 2.10686 |

| 6 | 47.7397 | 62.8871 | 5.07917 |

| 7 | 36.4784 | 62.8871 | −1.23344 |

| 8 | 95.223 | 51.3401 | 26.5839 |

| 9 | 63.5712 | 71.7297 | 27.5219 |

| 10 | 14.1603 | 60.6969 | 4.74213 |

| 11 | 1.63006 | 24.2887 | 5.00422 |

| 12 | 13.7232 | 80.4177 | 6.48784 |

| 13 | 15.6679 | 40.0944 | 4.24907 |

| 14 | 12.979 | 10.8809 | 5.16235 |

| 15 | 99.8925 | 21.8257 | 22.8288 |