It's not always histiocytic sarcoma: Immunocytochemistry to identify two unusual tumors in a Bernese Mountain dog

Abstract

A 7-year-old female spayed Bernese Mountain dog was presented for evaluation of hematuria. Incidentally, a right stifle sarcoma was diagnosed via cytology, which raised concern for histiocytic sarcoma (given the patient's signalment) versus another joint-associated sarcoma. Histopathology and immunohistochemistry revealed a CD18-negative, non-histiocytic origin cell population. Findings were consistent with a joint-associated grade II soft tissue sarcoma (STS). The patient's hematuria was progressive over 5 months, and urinary bladder transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) was diagnosed via cystoscopy and histopathology. An enlarged right medial iliac lymph node was identified on routine restaging via abdominal ultrasound 3 months later. Cytology of the lymph node revealed a markedly pleomorphic cell population, again raising concern for histiocytic sarcoma (HS). Other differentials included an anaplastic metastatic population from the joint-associated STS or the TCC. Immunocytochemistry revealed a cytokeratin-positive, CD18-, CD204-, and vimentin-negative cell population, consistent with a carcinoma. DNA was extracted from cytology slides to sequence cells for BRAF mutation status. Sequencing revealed a homozygous V596E (transcript ENSCAFT00845055173.1) BRAF mutation, consistent with the known biology of TCC. In neither case was HS truly present in this patient, but immunocytochemistry provided information that helped to optimize the patient's chemotherapy recommendations.

1 CASE PRESENTATION

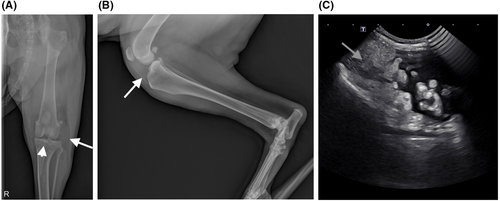

A 7-year-old female spayed Bernese Mountain dog presented for evaluation of hematuria on April 9, 2022. Abdominal ultrasound revealed a mobile structure within the urinary bladder, consistent with a hematoma, with no apparent bladder or urethral mass lesion. At the time of abdominal ultrasound, bilateral stifle effusion was noted, and specifically, right stifle thickening was palpated while the patient was being placed in dorsal recumbency for the ultrasound evaluation. A partial cranial cruciate ligament tear was believed to be the cause of left stifle effusion. Targeted musculoskeletal ultrasonographic evaluation of the right stifle revealed a 3.6 × 1.6 cm, heterogeneous, solid mass lesion at the lateral aspect of the right stifle joint. There was a large pocket of anechoic fluid at the level of the right proximal tibial diaphysis. Soft tissues at the medial and cranial aspects of the right stifle were thickened and heterogeneous (Figure 1).

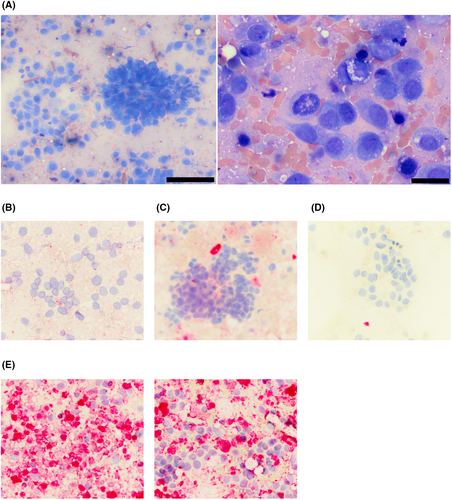

Aspirates of the mass lesion and associated joint fluid revealed a pleomorphic spindle cell population with moderate anisokaryosis and anisocytosis, most indicative of a sarcoma (synovial vs histiocytic origin), as well as moderate mononuclear inflammation (Figure 2A). Given the patient signalment, further evaluation of the sample for histiocytic origin was elected. Immunocytochemistry for CD204 was performed on cytology samples at Colorado State University (CSU). The negative control was adequate (BOND Ready-to-Use Negative Control Negative (Mouse), Catalog Number PA0996, Leica Biosystems, Newcastle Upon Tyne, United Kingdom), and atypical cells were negative for CD204, while normal tissue macrophages were positive (BOND Polymer Refine Red Detection, Leica Biosystems, Newcastle Upon Tyne, United Kingdom), which was consistent with a diagnosis of a sarcoma that was non-histiocytic in origin (Figure 2B).

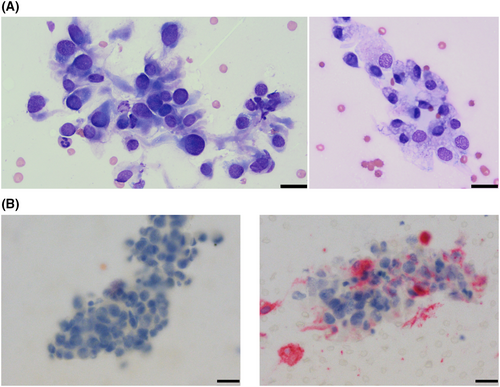

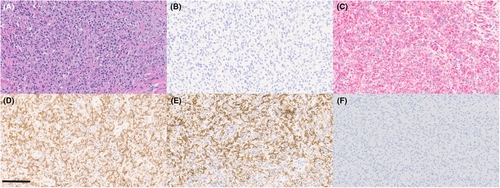

Following a diagnosis of sarcoma, abdominal and thoracic computed tomography (CT) scans were recommended to screen for possible disseminated disease. No abdominal or thoracic abnormalities were identified on the images obtained. Due to patient discomfort, the right pelvic limb was subsequently amputated. There was no histologic evidence of metastatic neoplasia in the local popliteal lymph node following amputation of the right pelvic limb. Histology of the mass lesion revealed a population of spindle cells that had overlapping features of synovial soft tissue sarcoma (STS; poorly circumscribed, multinodular neoplasm of dense spindle cells encapsulating the stifle joint) vs synovial histiocytic sarcoma (SHS; nodular synovial ingrowths). Figure 3 shows tumor histopathology. Morphologically, STS was favored, and CD18 immunohistochemistry (IHC) was negative. At this time, the anatomic pathologist recommended additional histiocytic tumor markers (CD204 and Iba1) on the joint tissue block if there was high concern for HS, based on the patient's breed; however, these were not pursued given the patient's clinical progression, previous ICC results, overall impression on histology, and CD18 negativity on IHC. Monitoring for progression of disease was recommended.

Meanwhile, the patient's hematuria was persistent and progressive, and she developed a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (MRSP) urinary tract infection in June 2022. A pathologist review of the urine sediment noted a significant neutrophilic inflammatory response with rare urothelial cells; these cells exhibited mild to moderate atypia, and dysplastic change secondary to inflammation was prioritized. The patient became anemic secondary to marked hematuria and ultimately required multiple blood transfusions. Cystoscopy was performed on 9/13/22, and there was proliferative tissue extending from the vestibule to the urethra on the right side of the bladder. Antech Cadet BRAF mutation analysis of the urine revealed a positive result (up to 6% mutated cells in the sample), and biopsy of the proliferative tissue was consistent with transitional cell carcinoma (TCC). The patient was started on carprofen therapy and then treated with fractionated intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) for her bladder/urethral mass. In total, 15 fractions of 3.2 gray (Gy) were administered. Hematuria resolved after beginning carprofen therapy and following IMRT. Two weeks after completion of the IMRT protocol, vinblastine chemotherapy was initiated.

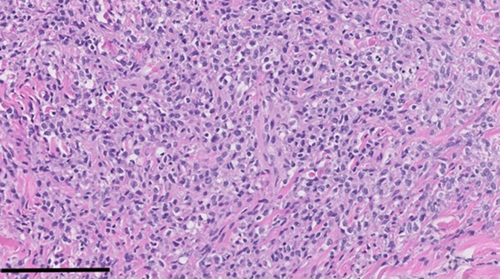

On 12/23/22, the patient was evaluated for evidence of metastatic neoplasia as part of routine restaging while undergoing vinblastine chemotherapy. On abdominal ultrasound, a 1.8 cm nodule in the cranial pole of the right medial iliac lymph node (RMILN) was identified. Aspirates of the RMILN revealed a pleomorphic population of discrete to aggregated, round to spindle-shaped cells, which were individualized or in epithelioid aggregates. Cells were commonly associated with fine, vascular structures throughout the sample (Figure 4A).

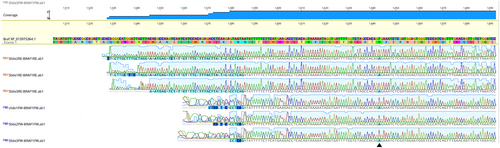

At this time, given the patient signalment and appearance of the cells, there was again concern for histiocytic neoplasia, which could have arisen de novo or potentially from the joint-associated tumor (if the original tumor was SHS). Other differentials included a metastatic STS or synovial cell sarcoma (SCS) from the joint (given the presence of epithelioid aggregates of cells and their perivascular arrangement),1 or potentially, anaplastic, metastatic carcinoma from the patient's TCC. Immunocytochemistry was performed through Colorado State University Diagnostic Laboratory on aspirate slides of the RMILN and revealed a cell population that was negative for CD18, CD204, and vimentin, but strongly positive for cytokeratin, consistent with an anaplastic epithelial cell population (Figure 4B–E). To further validate that these cells were truly metastatic from the bladder mass, DNA was extracted from slides and sequenced. In comparing results to known BRAF variants in dogs, these cells had a homozygous BRAF 596 V to E missense mutation, as previously described in dogs (Figure 5).2 To ensure that the original synovial tumor was not, in fact, related to the patient's bladder mass, Uroplakin III IHC was performed through Cornell Animal Health Diagnostic Center on the synovial tissue block, which was negative, as expected (Figure 6F).3 In addition, IHC for cytokeratin (Novocastra Liquid Mouse Monoclonal Antibody Multi-Cytokeratin (AE1/AE3), Leica Biosystems, Newcastle Upon Tyne, United Kingdom), CD18, and CD204 (Novocastra Liquid Mouse Monoclonal Antibody Vimentin, Leica Biosystems, Newcastle Upon Tyne, United Kingdom) were negative in the synovial tumor population, while cells were strongly positive for vimentin (CD204, Clone SRA-E5, Trans Genic Inc., Tokyo, Japan) (all performed by Kansas State Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory; Figure 6B–E). Overall, these data support the diagnosis of a synovial soft tissue sarcoma for the original joint tumor and a diagnosis of metastatic TCC in the lymph node aspirate.

2 DISCUSSION

There are striking morphologic similarities among synovial STS, SCS (or “cytokeratin-positive joint associated sarcoma”), and HS, both via cytology and histopathology. The present case, which grossly and histologically had features indicative of both SHS and synovial STS, illustrates this well.

In a recent paper, readers are reminded that the use of CD18, a pan-leukocyte marker, is considered critical in the diagnostic investigation of HS (expected CD18 positive) versus SCS (expected CD18 negative) in histopathology.1 Multiple canine neoplasms originally classified as SCS have been reclassified as SHS following appropriate IHC labeling, including CD18 positivity.4

In our case, negative IHC staining for CD18 and negative ICC staining for CD204 supported the diagnosis of a non-histiocytic, mesenchymal neoplasm of the joint. Some cytologic features that have been described as morphologically indicative of SCS, including epithelioid aggregation and perivascular arrangement,1 may be seen in other tumor types with good vasculature, including HS, the epithelioid variant of hemangiosarcoma (HSA), osteosarcoma (OSA), and the metastatic TCC described in this case.5-9 ICC labeling for the markers suggested by Monti et al is readily available at some institutions, including CSU, and can help to further characterize neoplastic cells. Relevant markers for joint-associated sarcomas include vimentin, cytokeratin, smooth muscle actin, and one marker for hematopoietic lineage (CD18 or Iba1 are suggested by this paper).1 Interestingly, the original rationale for the utilization of cytokeratin to identify SCSs was based on the minority of cytokeratin-positive epithelioid cells in biphasic human synovial sarcoma. Human “synovial sarcoma” is no longer believed to be of synovial origin, but rather, of pluripotential mesenchymal stem cell origin, and biphasic synovial sarcoma is either rare or nonexistent in domestic animals. Thus, additional investigation of canine joint tumor histogenesis is ultimately needed to determine why cytokeratin positivity is a persistent finding in canine synovial tumors.4, 10 Rare, benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors in dogs are cytokeratin positive, but this is otherwise an unusual finding in mesenchymal neoplasms.11, 12

While HS was suspected in two distinct locations in the case presented here, based on the patient signalment and cellular morphology of aspirated material from these sites, in neither location was HS truly present. Caution is always warranted in cytologic assessment, but this is especially relevant when cells are difficult to classify, there is morphologic overlap between multiple cell types, and there is the potential for cognitive bias (for example, as may occur when considering the predilection for HS in Bernese Mountain Dogs). Thankfully, additional classification of cells was pursued, and in this case, diagnostic efforts were aided significantly by ICC, which correctly classified cells from both lesions and guided appropriate chemotherapy recommendations. As additional markers are validated for clinical use, the classification of more ambiguous cell populations will undoubtedly improve cytologic diagnosis and patient care. For this patient, Uroplakin III could have been considered a useful addition to the patient's ICC panel.

Ultimately, BRAF mutation status was used to determine that the metastatic cell population was, in fact, of urothelial origin. BRAF is a kinase in the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway and is mutated in approximately 70%–85% of TCCs, leading to constitutive MAPK activity, cellular proliferation, and cancer cell survival.2, 13, 14 The V596E (valine to glutamic acid) BRAF mutation has been described previously in canine TCC, but homozygosity is atypical.2 Results from the urethral mass cytology sample sequencing could not be readily compared with urine BRAF mutation data, so it is unknown whether the tumor previously had homozygous BRAF mutations at the time of presentation or if the neoplasm evolved post-chemotherapy and radiation therapy to have mutations on both alleles. Although not readily available as a commercial diagnostic assay, the methods employed in this assay are readily achievable and could be valuable in other instances in which a metastatic cell population is believed to be of urothelial cell origin if cytologic smear cellularity is adequate.13

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.