Multi-institutional retrospective study of canine foot pad malignant melanomas: 20 cases

Abstract

Melanomas arising from the foot pad are a rare clinical entity in dogs. The biologic behaviour of foot pad malignant melanoma is not well understood, and these tumours are infrequently described. The objective of this study was to evaluate the clinical characteristics of primary canine foot pad melanoma in a larger cohort of patients. Eligible cases were solicited from the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) Oncology listserv for retrospective review. Included dogs had a cytologic and/or histologic diagnosis of foot pad melanoma evaluated by a board-certified clinical or anatomic pathologist. Dogs with cutaneous, oral, digital, subungual or interdigital melanomas were excluded. A total of 20 cases were included. Eleven dogs received various adjuvant therapies including chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and/or the ONCEPT canine melanoma vaccine following surgery. At diagnosis, regional lymph node metastasis was observed in four dogs (20%). Seven dogs developed subsequent regional and/or distant metastasis for an overall metastatic rate of 55%. The progression-free interval (PFI) was 101 days (range, 20–960 days). The median survival time (MST) was 240 days (range, 25–479 days). For dogs receiving adjuvant therapy, the MST was 159 days (range, 25–387 days). Canine foot pad melanoma is a rare neoplasm that can exhibit an aggressive behaviour.

1 INTRODUCTION

Malignant melanoma (MM), a tumour of melanocytes, is a common neoplasm in dogs arising from highly pigmented sites such as the oral cavity, lip, skin and nailbed.1, 2 The biologic behaviour of canine melanoma varies depending on a multitude of factors with anatomic location being one of the most useful predictors of prognosis.3, 4 MM in the oral cavity exhibits an aggressive behaviour with both local and distant invasion whereas cutaneous MM has a more benign behaviour with low recurrence (8%) and metastatic rates (21.8%) following local surgical resection.3, 5, 6 Other previously documented prognostic factors for canine MM include tumour size, clinical stage, mitotic index, and nuclear atypia and the Ki67 proliferative index.1 These factors can help with predicting biologic behaviour, although additional research is warranted given that melanomas have a variation in clinical behaviour.1, 7 Local therapy with surgery and/or radiation therapy remains the most effective treatment for the management of MM. The role of adjuvant therapy remains controversial.8-11

Canine foot pads are heavily pigmented tissue making them possible sites for MM to arise. However, melanomas arising from the foot pad are a rare clinical entity in dogs accounting for only 1.8% (7/384) of all melanocytic tumours.3 The biologic behaviour of foot pad MM is not well understood, and these tumours are infrequently described.3, 7 Melanomas of the canine foot have been reported in one study as having a higher likelihood of being histologically malignant.7 However, when compared to tumours that arise from the skin, the behaviour did not differ significantly. Additionally, the study did not distinguish between different locations on the foot such as the digit, nail bed, pad or dorsal surface. Another recent study compared the characteristics of MM arising from the feet and lips to those arising from the oral cavity.3 In that study, melanomas of the feet and lips had a lower percentage that demonstrated malignant behaviour (38%, compared to 59% of oral melanoma cases), and had a lower likelihood of melanoma related death (30%, compared with 68% of oral melanoma cases). In that group, 21.8% (7/32) of the melanomas were of the foot pads and varied in behaviours including three that showed evidence of malignancy.

Overall, small numbers of foot pad melanomas have been reported in dogs. To the authors' knowledge, no large data set of canine melanomas of the foot pad has been published. The purpose of this multi-institutional retrospective study was to evaluate the clinical characteristics of cytologic and/or histologic confirmed primary canine foot pad melanoma in a larger cohort of dogs The primary objectives were biologic behaviour, clinical outcome, and potential prognostic factors in the study population.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Case selection

A multi-institutional, retrospective study of client-owned dogs with a diagnosis of foot pad melanoma was performed. Cases were requested using the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine Oncology electronic mailing list. Contributors were sent abstracting forms and cases were extracted at their respective institutions. A medical records search was performed from 2002 to 2020 at 11 academic and referral institutions. Dogs were included if they had a cytologic and/or histologic diagnosis of foot pad melanoma evaluated by a board-certified clinical or anatomic pathologist. Dogs with cutaneous, oral, digital, subungual or interdigital melanomas were excluded. To be eligible for inclusion, complete medical records and follow-up information for at least 8 weeks following diagnosis were required.

2.2 Medical records review

Information obtained from the medical records included the following: age, weight, sex, breed, clinical signs at diagnosis, date of diagnosis, tumour size, presence or absence of ulceration and foot pad location. Staging diagnostics and results were recorded, when available. Stage was determined according to the WHO staging system, however complete staging was not required for study inclusion. Tumour-specific variables, when available from the histopathology reports, included mitotic count (MC), completeness of excision and histochemical and immunohistochemical staining. MC was defined as the number of mitotic figures in 10 consecutive high-powered fields. If a dog had more than one MC reported, the highest MC was recorded for use in this data set. Surgical margins were classified as complete if no tumour cells were observed at the edges of the sample and classified as incomplete if any tumour cell were observed at the edges of the sample. As pathology reports were only reviewed, techniques related to margin assessment were not routinely reported or known. Types of local and adjuvant treatments such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, chemotherapy, radiation therapy and ONCEPT vaccine (Merial Limited, Duluth, GA) were recorded. Outcome information, including local recurrence, distant metastasis, date of death and cause of death was obtained from the medical record or the referring veterinarian when available.

2.3 Statistical analysis

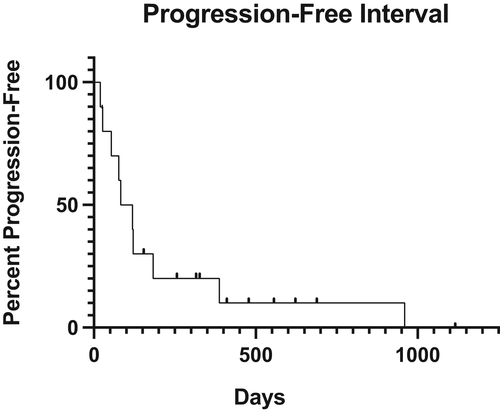

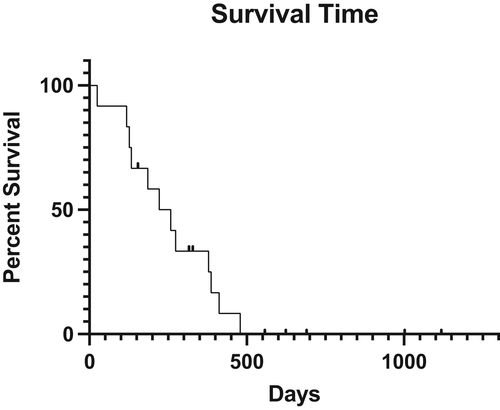

Patient outcomes were described as progression-free interval (PFI) and median survival time (MST). The PFI was defined as the time from diagnosis to the time of local recurrence or metastasis. Dogs that died and did not have local recurrence or noted metastasis at the time of death were censored from PFI. MST was defined as the time between time of diagnosis and the time of death. Melanoma-specific survival was defined as the time of diagnosis and the time of death from malignant melanoma. Kaplan–Meier analysis were used to estimate and display the distribution of PFI and ST (Prism 7, GraphPad, San Diego, California). The cause of death was determined from the medical records or after follow-up with the referring veterinarian. If cause of death was unknown, then these deaths were attributed to melanoma. Dogs were censored from outcome data if they died from unrelated causes, were alive at the time of manuscript preparation or were lost to follow-up.

2.4 Cell line validation statement

This study did not involve cell lines; therefore, cell line validation work was not carried out.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Patient characteristics

Twenty dogs met the inclusion criteria from 11 institutions (Colorado State University (n = 3), The Ohio State University (n = 3), Veterinary Emergency and Referral Center of Hawaii (n = 3), Oregon State University (n = 2), University of California Davis (n = 2), Anderson Moores Veterinary Specialists (n = 1), Blue Pearl Rockville (n = 1), Blue Pearl Specialty and Emergency Pet Hospital (n = 1), Bridge Animal Referral Center (n = 2), Central Texas Veterinary Specialty and Emergency Hospital (n = 1) and Hope Veterinary Specialists (n = 1)). The median age at diagnosis was 10.5 years (range, 5.2–15 years). The median weight was 31.7 kg (range, 7–42 kg). Weight was not available in one case. Breeds represented included Labrador retriever (n = 5), mixed breed (n = 4), miniature schnauzer (n = 3) and one each of the following, Brittany spaniel, flat-coated retriever, French bulldog, giant schnauzer, golden retriever, Norwich terrier, rottweiler and standard schnauzer. There were 13 (65%) neutered males, 6 (30%) spayed females, and 1 (5%) intact male dog. Complete patient demographics are listed in Table 1. Clinical signs were reported and available in 19/20 (95%) cases. Lameness (n = 8, 40%) and appreciation of a foot pad mass (n = 8, 40%) were the most common clinical signs. Other clinical signs noted were malodor (n = 1, 5%) and chewing of the mass (n = 1, 5%).

| Characteristics | Number of dogs | |

|---|---|---|

| 20 | ||

| Age (years) | (Median, range) | 10.5, 5.2–15 |

| Sex | MN | 13 (65%) |

| FS | 6 (30%) | |

| M | 1 (5%) | |

| Weight (kg) | (Median, range) | 31.7, 7–42 |

| Affected foot pad location | Metacarpal | 10 |

| Metatarsal | 7 | |

| Digital pad | 3 | |

| Left carpal pad | 1 |

Concurrent morbidities included low-grade cutaneous mast cell tumours removed at the time of foot pad melanoma surgery (n = 2), renal epithelial neoplasia (n = 1), hyperadrenocorticism and prior history of a cutaneous melanoma (n = 1), splenic mantle zone lymphoma, cholangiosarcoma and trichoepithelioma (n = 1), and multicentric lymphoma (n = 2); one dog with multicentric lymphoma was enrolled into an anti-B cell clinical trial.

3.2 Tumour location and gross characteristics

Foot pad melanoma location was reported in all dogs (Table 1). A singular foot pad site was affected in 19/20 dogs (95%). One dog had two separate foot pad sites affected concurrently. The most common pad affected were the metacarpal pads,10 metatarsal pad,7 digital pad3 and carpal pad.1 Tumour size was recorded in 18 of 20 dogs. Accounting for the largest tumour diameter, the median pre-surgical tumour size was 12 mm (range, 2–22 mm). Ulceration of the tumour was documented in 13 cases (65%). Four dogs had no evidence of ulceration and three had no report of ulceration status.

3.3 Initial dog staging and tumour pathologic features

Initial baseline diagnostics performed included a complete blood count in 17/20 (85%), serum biochemistry in 17/20 (85%), and urinalysis in 2/20 (10%) dogs. Thoracic imaging was performed in 18/20 dogs (90%) predominately with radiography (17/18) and with computed tomography in one case. None of the dogs with thoracic imaging had evidence of thoracic metastatic disease at diagnosis. Abdominal ultrasound was performed in seven cases (35%). One dog had a heterogenous spleen, a hypoechoic area associated with the prostate, and a right renal mass. Fine needle aspirates performed revealed lymphoid hyperplasia of the spleen and a cystic epithelial neoplasm of the kidney. The prostatic aspirates were inconclusive due to haemodilution. No other significant abnormalities were documented on abdominal ultrasound for the other six cases. Other imaging diagnostics included radiographs and focal ultrasound of the affected foot pad in one dog. On ultrasound, a focal defect of the metacarpal pad was identified. There was concurrent swelling of the pad and a focal diffuse hyperechoic area deep to the skin surface. Radiographs of the foot were not available for review.

On initial examination, regional lymph node enlargement was observed in 11/20 dogs (55%). Prominent lymph nodes affected the ipsilateral side with superficial cervical7 and popliteal4 lymphadenomegaly. The regional lymph node was evaluated in 16/20 dogs (80%) by cytology and/or histopathology. Four dogs had confirmed metastatic disease of the lymph node; two were confirmed on cytology and two were confirmed on histopathology. Of the four dogs with pathology-confirmed lymph node involvement, two dogs had an enlarged regional lymph node on examination. The regional lymph node metastatic rate for dogs was 4/20 (20%) at the time of diagnosis. In one dog, subcutaneous nodules in the left axilla were identified on physical exam on initial presentation. Histopathology of the axillary nodules revealed a moderately differentiated malignant melanoma. On review, the lesion may have represented a de novo solitary event or subcutaneous metastasis effacing a local small lymph node. However, no nodal architecture was detected.

MM diagnosis was confirmed pre-operatively by cytology in five dogs and post-operatively or via biopsy in all 20 dogs. The MC of the primary tumour was reported in 19 cases (Table 2) The median MC was 10 mitoses per 10 hpf (range, 1–48). Only one dog had the MI reported as 2 mitoses per hpf and was not included in the median. Four cases had histochemical and immunohistochemical (IHC) staining performed to confirm a melanoma diagnosis. SOX-10, S100, Melan-A, Fontana-Masson, CD18 and PLN-2 stains were utilized at the discretion of the pathologist.

| Breed | Regional lymph node evaluation at diagnosis | Primary treatment | Margin status | Revision surgery and margin status | MI | Developed metastasis and/or local recurrence | Adjuvant therapy | PFI (days) | MST (days) | Comorbidity | Follow-up/Cause of euthanasia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flat-coated retriever1 | Not performed | Surgical excision | Incomplete | Yes, complete | 1/10 hpf | Unknown | None | N/A | N/A | None | Alive |

| Miniature schnauzer2 | Reactive | Surgical excision | Complete | N/A | 5/10 hpf | No | None | N/A | N/A | Hyperadrenocorticism and previous history of melanoma | Alive |

| French bulldog3 | No evidence of metastasis | Surgical excision | Incomplete | Yes, complete | 6/10 hpf | Local recurrence | ONCEPT melanoma vaccine | 960 | N/A | Low-grade mast cell tumour and renal epithelial neoplasm | Alive |

| Labrador retriever4 | Metastatic | Surgical excision | Complete | N/A | 10/10hpf | Lung | Toceranib phosphate and dasatinib | 27 | 127 | None | Death due to melanoma |

| Rottweiler5 | Not performed | Surgical excision | Incomplete | No | 20/10 hpf | Lung | Carboplatin | 20 | 25 | Multicentric lymphoma | Death due to melanoma |

| Standard schnauzer6 | Metastatic | Surgical excision | Not available | N/A | 10/10hpf | No | None | N/A | N/A | None | Lost to follow-up (690 days) |

| Norwich terrier7 | Reactive | Surgical excision | Complete | N/A | 4/10 hpf | Lymph node and lung | One fraction of 8 Gy to metastatic lymph node | 121 | 133 | None | Death due to melanoma |

| Miniature schnauzer8 | Not performed | Surgical excision | Incomplete | Yes, complete | 4/10 hpf and 7/10 hpf | No | ONCEPT melanoma vaccine | N/A | N/A | None | Alive |

| Mixed breed9 | Reactive | Surgical excision | Not available | N/A | 12/10 hpf | Local recurrence, regional lymph node, lungs, and heart | None | 119 | 222 | Low-grade mast cell tumour | Death due to melanoma |

| Labrador retriever10 | Reactive | Surgical excision | Complete | N/A | 48/10 hpf | Lung | ONCEPT melanoma vaccine | 83 | 118 | None | Death due to progressive hematochezia |

| Labrador retriever11 | Reactive | Surgical excision | Incomplete | No | 2/hpf | Lung | Palladia, cyclophosphamide, 4 x 8 Gy to foot pad and lymph node, and ONCEPT melanoma vaccine | 183 | 379 | None | Death due to melanoma |

| Brittany spaniel12 | Reactive | Surgical excision | Incomplete | Yes, complete | 2/10 hpf | Unknown | None | N/A | Alive | None | Alive |

| Giant schnauzer13 | Reactive | Surgical excision | Incomplete | Yes, complete | 20/10 hpf | Unknown | None | N/A | 412 | None | Unknown |

| Labrador retriever14 | Reactive | Surgical excision | Not available | N/A | 2/10 hpf | Unknown | None | N/A | 479 | Multicentric lymphoma |

Death due to lymphoma |

| Golden retriever15 | Metastatic | Surgical excision | Not available | N/A | 30/10 hpf | Local recurrence, lungs, and heart | Gemcitabine and ONCEPT melanoma vaccine | 387 | 387 | Cholangiosarcoma, trichoepithelioma, and mantle zone lymphoma | Death due to melanoma |

| Mixed breed16 | Reactive | Electrochemotherapy | Incomplete | No | 11/10 hpf | Local recurrence | ONCEPT melanoma vaccine | 77 | 274 | None | Death due to melanoma |

| Mixed breed17 | Metastatic | Surgical excision | Complete | N/A | 26/10 hpf | Lung | Tremetinib and ONCEPT melanoma vaccine | 54 | 185 | None | Death due to melanoma |

| Miniature schnauzer18 | Reactive | Surgical excision | Incomplete | No | 3/10 hpf | Unknown | None | N/A | 258 days | None | Death due to oronasal fistulas |

| Labrador retriever19 | Reactive | Surgical excision | Complete | N/A | 1/10 hpf | Unknown | None | N/A | N/A | None | Lost to follow up (155 days) |

| Mixed breed20 | Not performed | Surgical excision | Complete | N/A | 14/10 hpf | Unknown | ONCEPT melanoma vaccine | N/A | N/A | None | Lost to follow up (557 days) |

3.4 Surgery and adjuvant therapy

Surgical biopsy and/or excision of the primary tumour was documented in all 20 dogs (Table 2). Complete surgical margins were reported in seven dogs, incomplete surgical margins were reported in nine dogs and margin status was not available in four dogs. Revision surgery was performed in 5/9 (55.5%) dogs with incomplete surgical margins. Surgical margin evaluation was complete in 4/5 dogs with revision surgery when reported. Adjuvant non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) use was recorded in one dog and used in two dogs for post-operative pain relief. Records of long-term NSAID was not available for the rest of the study population.

Eleven dogs (55%) received various adjuvant therapies following surgical excision (Table 2). Chemotherapy was utilized as adjuvant therapy in 6/20 dogs (30%). Chemotherapy agents included toceranib phosphate, dasatinib, carboplatin, cyclophosphamide, gemcitabine and trametinib. Rescue chemotherapy protocols were initiated following metastatic or progressive disease in three dogs. Following incisional biopsy, one dog was treated with four doses of bleomycin and one dose of carboplatin polymer electrochemotherapy to the foot pad site as a primary local treatment. This dog also received three doses of an autologous vaccine (Torigen Pharmaceuticals, Farmington, CT) from a lymph node sample.

Seven dogs received the ONCEPT melanoma vaccine. The vaccine was administered to four dogs as the only adjuvant therapy. The median number of doses was 4 (range, 2–8). Two dogs received radiation therapy (RT). One dog was treated with RT as the sole adjuvant therapy. This dog's treatment plan included three planned fractions of 8 Gy to the metastatic lymph node, but only received one fraction due to rapid and continuous clinical decline presumably due to progressive metastatic disease. The other dog received four fractions of 8 Gy for the treatment of an incompletely excised foot pad and regional lymph node prophylactically. Out of the total 20 dogs, 9 dogs (45%) did not receive adjuvant therapy.

3.5 Post-surgical restaging and dog outcome

Fourteen of twenty (70%) dogs were restaged following surgical resection at the discretion of the attending clinician. Restaging was not routine; the earliest time of restaging was 20 days after diagnosis and varied thereafter. Diagnostics performed included regional lymph node aspirates, thoracic radiographs, abdominal ultrasound, and thoracic and abdominal CT. Ten dogs were censored from PFI analysis. Four dogs were alive at the time of analysis with no evidence of recurrence or metastasis. Three dogs died and three dogs were lost to follow-up with no evidence of recurrence or metastasis. The median follow-up time for this group was 328 days (range 155–1118 days).

Ten dogs (50%) had progressive disease including suspected or confirmed local recurrence, development of metastasis to a distant site, metastasis to a regional lymph node(s), pulmonary nodules and heart nodules. Local recurrence occurred in three dogs. At the time of surgery, margins status was incomplete, complete and not reported respectively. The most common sites of metastasis included the lungs (n = 7), regional lymph node (n = 3) and heart (n = 2). The PFI was 101 days (range, 20–960 days) (Figure 1).

Eight dogs were censored from OST analysis; five dogs were alive at the time of manuscript analysis and three dogs were lost to follow-up. The median follow-up time was 557 days (range 155–690) for this category. The median survival time (MST) for death of any cause was 240 days (range, 25–479 days) (Figure 2). MST for melanoma-specific survival was 203 days (range, 25–387 days). For dogs receiving adjuvant therapy, the MST was 159 days (range, 25–387 days).

Post-mortem evaluation was performed in three dogs. Wide-spread metastasis was present in two cases. One dog was observed to have melanoma metastasis to the inguinal and iliac lymph nodes, the left ventricle of the heart, and lungs. Progressive lymphedema of the right hindlimb and difficulty breathing was appreciated leading up to euthanasia. The other dog had metastatic lesions of the lungs and right auricle. PLN-2 IHC showed strong cytoplasmic expression within the neoplastic cells of the lungs, however no staining was present of the right auricular mass. The third dog had an enlarged left superficial cervical and left popliteal lymph node twice the size of normal as well as a 2 cm lung nodule and 3–4 cm splenic body mass. On gross examination, the cut surfaces of the lymph nodes were black, however no further histopathology was performed.

Based on low case numbers and high censorship, prognostic factors were not assessed for significance.

4 DISCUSSION

This study reports the aggressive behaviour of canine malignant foot pad melanoma. Local recurrence and metastasis were documented in 55% of dogs, and five dogs were alive at the last follow-up. Most dogs were treated with local surgical resection; however similar to other anatomic sites of MM, the addition of adjuvant therapy did not appear to numerically improve survival. Prognostic comparisons were not able to be evaluated and additional studies are warranted to assess for significance.

The aims of this retrospective study were to report the biologic behaviour and clinical outcome of dogs diagnosed with primary foot pad melanoma. Our retrospective analysis is the first study to describe canine foot pad melanomas in a larger cohort of dogs. In a previous report, when comparing the survival data for dogs with melanomas of the foot versus melanomas of other skin sites, no significant difference was observed between ST or tumour related death.7 In that study, the specifics of foot location (skin, digit, pad) were not distinguished. To the authors' knowledge, the best described report of canine foot pad melanoma is from a larger study of 32 dogs that identified 7 dogs with primary foot pad melanomas.3 Of the seven dogs, three tumours were identified as malignant, and most dogs died from competing causes. Only one dog died as a result of the tumour. In contrast, our study documents a larger proportion of dogs succumbing to melanoma progression and demonstrates malignancy in all cases.

Notably, six dogs (30%) in this study had concurrent co-morbidities. The cases with high-grade malignancies such as lymphoma may have contributed to patient survival, however only one dog succumbed to this disease. In a previous study of dogs presenting to a veterinary teaching hospital, ~3% of new cases presented with multiple distinct tumours.12 While this overall number is lower compared to our study, 33% of thyroid tumours in a previous study were found to have a higher percentage of multiple tumour types similar to dogs with foot pad malignant melanoma.12 Interestingly, this study also found that dogs with mast cell tumour, malignant melanoma, and thyroid carcinoma were more likely to be diagnosed with multiple tumour types supporting the higher incidence of co-morbidities.

For dogs with foot pad MM, progression was defined as local recurrence and/or when locoregional and distant metastasis was observed. Over half of the dogs in this study had locoregional or distant metastasis. Only one dog had evidence of foot pad melanoma affecting two separate pads, and this dog was alive at the time of manuscript preparation. Interestingly, for three dogs with post-mortem examinations, cardiac metastasis was identified in two dogs. The heart has previous been reported as a metastatic site in dogs.2 Other reported sites of melanoma metastasis include the lymph nodes, lungs, liver and meninges.2 As not all dogs in this study had necropsies performed, future studies should consider evaluating the heart as a potential site of distant metastasis. In humans, cardiac metastasis has been reported in 47%–64% of melanoma patients on post-mortem evaluation.13, 14 Cardiac metastasis is more commonly noted as part of a disseminated process in people, but MM can show a high tendency for cardiac involvement despite the majority being clinically silent.

Eleven dogs in this study received adjuvant therapy. There was no standardized protocol and the adjuvant treatment varied. The MST for dogs treated with adjuvant therapy was 159 days. The use of adjuvant therapy was used primarily in dogs with incomplete surgical margins or evidence of overt metastatic disease. The inclusion of adjuvant therapy was not found to be clinically beneficial similar to previous reports on malignant melanoma.5, 8, 15 It is difficult to extrapolate a conclusion as not every dog had adjuvant therapy and an array of protocols used to evaluate the effects of treatments on survival time. Additionally, the decision to treat with adjuvant therapy was based on a variety of factors including client and patient related concerns.

Anecdotally, foot pad melanoma has been described as similar in metastatic potential and prognosis to digital melanoma.16 Digital MM has a reported MST of 12 months.17 In a recent report on cutaneous malignant melanoma, cutaneous MM of the digit (defined as a tumour affecting the haired skin overlying or distal to the metacarpals or metatarsals) did not behave as aggressively as other forms of cutaneous MM.6 This study found a median OST of 3 years for cutaneous MM of the digit. When comparing clinical outcome of these different paw locations, MM of the foot pad did not have a longer survival outcome compared with malignant melanoma of the digit.6, 17 Overall, canine MM of varied anatomic sites is a heterogenous tumour, and the behaviour of canine MM is diverse and dependent on several factors. For dogs with oral MM, these factors include tumour size, location within the oral cavity, and histologic features.1 These factors may be important in dogs with foot pad MM; however, this could not be appropriately assessed in our data set due to varied treatment and high survival censorship.

Foot pads are naturally a heavily pigmented tissue consisting of multiple pads (digital, metacarpal/metatarsal, and carpal/tarsal pads).18 Breeds such as miniature schnauzers, standard schnauzers and Scottish terrier were at an increased risk of developing melanoma.19 Labrador retriever (n = 5) and Schnauzer breeds (n = 5) were overrepresented in our study cohort. Malignant melanoma often grows rapidly and is commonly ulcerated.19 Ulceration generally indicates a locally advanced disease with an increased risk of metastasis in dog melanocytic neoplasms.2 In our data set, a large proportion of dogs had ulceration at the foot pad, however assessment of impact on disease course was not assessed due to low patient numbers and patient censorship.

In comparison, cutaneous melanoma of the palms, soles and nail beds of people also known as acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM), has been documented as a histological subtype of melanoma. ALM are represented higher in populations with darker skin tones compared with those of lighter skin.20, 21 ALM has been described as the least common subtype of MM and is associated with a poor prognosis as they often have advanced disease because of delays in diagnosis.21 The likely multifactorial pathogenesis remains controversial with some potential associations to mechanical injury. However, exposure to UV light has been disfavored as these locations are sun shaded.

The retrospective nature of this study inherently presented several limitations. Follow-up diagnostics and recorded clinical information was inconsistent across cases. The small number of dogs was a limiting factor due to the low incidence of melanomas arising at this location. Even as a multi-institutional study, only 20 cases met our inclusion criteria. Medical records also varied between different institutions and there was no standardized tumour staging, treatment or follow-up protocols. Our aim to identify potential prognostic factors was not achieved. Based on the number of censored cases, further statistical analysis with defined survival or progression endpoints for prognostic significance could not be evaluated. Additionally, a complete pathologic review to evaluate all foot pad specimens for histopathologic features and numeric margin status was not pursued. Furthermore, histopathology reports including tumour features and mitotic count were not standardized.

In conclusion, our study identified that canine footpad melanoma can exhibit an aggressive behaviour. However, 10 dogs were censored for PFI analysis, and eight dogs censored for ST (median follow-up time was 557 days, range, 155–690). In cases with potential aggressive features, adjuvant therapy may be warranted but numerically did not result in a survival benefit in this study. A larger cohort is needed to evaluate factors with prognostic significance, to better assess the effect of treatment on foot pad melanoma, and to further characterize this rare entity of malignant melanoma.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr Krystal Harris (Central Texas), Dr Christine Mullin (Hope Veterinary Specialists), Dr Rachel Rasmussen (BluePearl Rockville), Dr Timothy Rocha (BluePearl Speciality + Emergency Pet Hospital), and Dr Katarzyna Purzycka (Anderson Moores Veterinary Specialists) with case contribution and data collection.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The authors have no financial support to disclose.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.