Ventral mandibulectomy for removal of oral tumours in the dog: Surgical technique and results in 19 cases

Abstract

The purpose of this retrospective study is to describe in detail a novel ventral approach for mandibulectomy and the results in 19 dogs. The medical records of 19 dogs that received a partial or total unilateral mandibulectomy with the new ventral approach were reviewed. Information obtained included signalment, tumour type, extent of mandibulectomy, removal of regional lymph nodes, intrasurgical complications, immediate postoperative complications, histopathological diagnosis and study of margins. Intrasurgical complication occurred in one dog (haemorrhage) and required a blood transfusion. Postoperative morbidity was minor and included transient ventral cervical swelling and self-limiting sublingual swelling (two dogs). All 19 animals were discharged between 24 and 48 hours of the procedure, and appetite was considered normal at discharge. Some perceived advantages of this procedure include easy identification of all the important anatomic structures in the area, including the inferior alveolar artery and temporo-mandibular joint, and the fact that osteotomy of the zygomatic arch is not necessary (in case of caudal mandibulectomy). In addition, dissection of both mandibular and retropharyngeal lymph nodes is easily achieved by caudal extension of the same skin incision.

1 INTRODUCTION

Oral neoplasia is common in dogs, accounting for 6% of all canine tumours.1 Melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, fibrosarcoma and osteosarcoma are the oral tumours most commonly diagnosed in dogs.2 Treatment for oral malignancies varies, but wide surgical excision with removal of variable extents of the mandible, is commonly undertaken to attempt local disease control. The extent of the mandibulectomy is dictated by tumour location, size and type.3 A technique for unilateral total mandibulectomy or caudal mandibulectomy has been reported by Withrow and Holmberg. It describes a full-thickness incision on the lip commissure with the patient in lateral recumbence. This incision may sever branches of the facial artery and vein, which are then ligated. Removal of the zygomatic arch (for caudal mandibulectomy) is also recommended for adequate exposure of the ramus.4 At the end of the procedure, the zygomatic arch is replaced with 20-gauge wire at each end of the bone. A different approach (intra-oral) was described by Harvey. In such technique, the whole procedure is performed within the oral cavity with the dog in sternal recumbency.5

In the present study, we describe a novel ventral approach to the mandible for purposes of caudal mandibulectomy or total unilateral mandibulectomy. Perceived advantages of ventral mandibulectomy include the ease of the procedure, direct visualization of the inferior alveolar artery (as it enters the mandibular foramen) and the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), and ready access to mandibular and retropharyngeal lymph nodes for removal without the need to reposition the patient. Owing to great visualization of the muscles in the area, en bloc resection of aggressive tumours can be achieved with confidence. Furthermore, in cases where the tumour is located in the caudal mandibular body or ramus, morbidity may be decreased because osteotomy of the zygomatic arch is not necessary.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

Medical records from patients that received ventral mandibulectomy were reviewed. Information obtained included signalment, breed, age, imaging modality before surgery, the extent of surgical resection, regional lymph node removal (mandibular, retropharyngeal, unilateral or bilateral removal), intra-operative complications, postoperative complications, time to discharge, histopathological diagnosis, metastasis to regional lymph nodes and study of margins.

2.1 Surgical technique

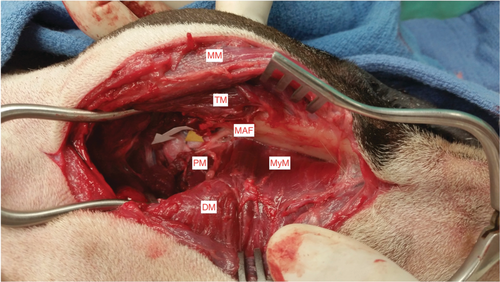

The patient is positioned in dorsal recumbency. A sandbag is placed under the neck to allow the mandibular body to be parallel to the surface of the operating table. The mouth may be held open with a mouth gag (on the unaffected mandibular canine teeth) and absorbent pharyngeal sponges are placed in the nasopharynx. The body of the mandible of the affected side is palpated before the skin incision. The extent of the skin incision is dependent on the extent of the mandibular segment to be removed. The skin incision is extended caudally to the level of the angular process of the mandible. Haemorrhage from small vessels is controlled with electrosurgery. The platysma muscle is incised first followed by incision of the insertions of the digastricus muscle on the ventromedial and the middle portion of masseter muscle, on the ventrolateral aspect of the mandibular body, respectively. The mylohyoideus muscle (which can be seen originating on the medial aspect of the mandible as it forms a ventral sling for the tongue) is severed. Its cranial fibres are opposite to the first premolar tooth and the caudal fibres are just caudal to mandibular third molar, which exposes the mandibular bone.6 The inferior alveolar artery is identified as it enters the mandibular foramen on the medial and caudal aspect of the mandible.6 The artery is electrocoagulated or double-ligated depending on its size. The remaining soft tissues are dissected off the lateral and medial walls of the mandibular body, and then the oral mucosa is incised with a scalpel blade exiting into the oral cavity. Care is taken not to damage the tongue. The mucosal incision is extended as rostral and caudally as necessary to allow the mandibulectomy. In cases of total unilateral mandibulectomy, the symphysiotomy is performed, and the rostral tip of the affected mandible is then pulled through the skin incision, allowing for easier identification and dissection of muscles of the caudal mandibular body and ramus. The authors routinely perform the mandibular osteotomy with an oscillating saw. It is important to note that there are multiple available devices including precise oral surgery hand-pieces that can be used depending on surgeon's preference and equipment availability. As the osteotomy is being performed, sterile saline is dripped over the blade to avoid overheating and subsequent bone necrosis. The insertion of the superficial portion of masseter muscle is visualized on the masseteric fossa, on the lateral aspect of the ramus of the mandible and ventral to the zygomatic arch.6 The insertion of the masseter muscle is severed with the use of periosteal elevators and electrosurgery. Next, the pterygoideus lateralis and medialis muscles can be seen. The pterygoideus lateralis inserts on the medial surface of the mandibular condylar process, just ventral the mandibular articular surface, and the pterygoideus medialis muscle inserts on the angular process of the mandible.6 The temporalis muscle is visualized as it inserts on the coronoid process of the mandible. Manipulation of the cranial aspect of the mandible allows for easy identification of the insertions of pterygoideus and temporalis muscles and the TMJ (Figure 1). These muscles are then severed adjacent to the joint. It is important to note that all muscles attaching to the mandible are cut with variable margins as needed for en bloc resection, depending on tumour location.

Disarticulation of the TMJ is achieved by careful sharp dissection with a 15-scalpel blade, as the joint is being manipulated to allow its precise location. Once this is achieved, the remaining muscular attachments to the mandibular ramus (temporalis and mandibuloauricularis) are progressively cut. Care should be taken to avoid severing the mandibular portion of the maxillary artery, which runs from lateral to medial just caudal to the TMJ6 (Figure 1). Following removal of the mandible, the wound is closed in the following layers: (a) the oral mucosa is closed first from inside the wound with absorbable material in a simple continuous pattern; (b) mylohyoideus, digastricus and the rostral portion of the masseter muscle are apposed with absorbable material in a single continuous pattern; (c) the pterygoideus, temporalis, and caudal portion of the masseter muscles are apposed with absorbable material in a simple continuous pattern; (d) the subcutaneous layer is closed in a simple continuous pattern (e) the skin is apposed with non-absorbable suture in an interrupted pattern (Figure 1).

In cases where lymph node removal is indicated, the skin incision for the mandibulectomy is continued caudally, extending just caudal to the ipsilateral mandibular salivary gland. Next, the platysma muscle is incised. The mandibular lymph node is easily visualized rostral to the mandibular salivary gland and within the bifurcation of the jugular vein into facial and lingual veins. The retropharyngeal lymph node is identified next, with dissection that starts medial and extends dorsomedial to the mandibular salivary gland. Their removal is performed similarly to what has been recently described by Green and Boston.7

On the 24 hours following the surgical procedure, the patients continued to receive intravenous fluids, antibiotics, opioids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs at the discretion of the surgeon. The authors routinely recommend icing the incision for 20 minutes, 3 to 4 times daily for 72 hours to control ventral cervical oedema formation.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Patients

Information about the patients and the procedure is outlined in Table 1.

| Breed | Sex | Age | Pre-operative image planning CT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cocker Spaniel | FS | 12 years | HNC |

| Golden Retriever | FS | 10 years | HNC |

| Yorkshire Terrier | FS | 13 years | HNC |

| Mix breed | MC | 11 years | HNC |

| Mix breed | MC | 14 years | HNC |

| Mix breed | MC | 11 years | Head |

| Labrador Retriever | MC | 7 years | HNC |

| Mix breed | FS | 10 years | HNC |

| Mix breed | FS | 12 years | HNC |

| Mix breed | MC | 8 years | HNC |

| Boston Terrier | FS | 11 years | HNC |

| Labrador Retriever | FS | 8 years | Head |

| Jack Russel | FS | 9 years | HNC |

| Staffordshire Terrier | MC | 6 years | HNC |

| Labrador Retriever | MC | 11 years | HNC |

| West Highland Terrier | FS | 6 years | Head |

| Border collie | MC | 9 years | HC |

| Mix breed | FS | 13 years | HC |

| Australian Cattle Dog | FS | 14 years | Head |

- Abbreviations: HNC, head, neck and chest; HC, head and chest; MC, male castrated; FS, female spayed; CT, computed tomography.

Three institutions contributed the cases: The University of Florida (11 cases), Fitzpatrick Referral Hospital, UK (7 cases) and The Ohio State University (1 case).

The extent of the surgery and postoperative information is depicted in Table 2.

| Surgery | LN resection | Operative complications | Post-operative complications | Diagnosis | LN status | Margins |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Segmental | None | None | Mild swelling | Melanoma | N/A | Complete |

| Caudal | Bilateral M/R | Haemorrhage | Mild swelling | OSA | + | Complete |

| Segmental | M/R | None | Mild swelling | Melanoma | None | Complete |

| TUM | None | None | Mild swelling | Ameloblastoma | N/A | Complete |

| TUM | Bilateral M/R | None | Mild swelling | Melanoma | None | Complete |

| TUM | Bilateral M/R | None | Mild swelling | SCC | None | Complete |

| TUM | None | None | Mild swelling | OSA | N/A | Complete |

| TUM | Bilateral M/R | None | Mild swelling | OSA | None | Incomplete |

| TUM | Bilateral M/R | None | Mild swelling | SCC | None | Complete |

| TUM | M | None | Mild swelling | OSA | None | Complete |

| Segmental | None | None | None | Epulis | N/A | Complete |

| TUM | Bilateral M/R | None | None | OSA | None | Complete |

| Caudal | M/R | None | Mild swelling | FSA | None | Complete |

| Caudal | Bilateral M/R | None | None | FSA | None | Complete |

| TUM | Bilateral M/R | None | None | SCC | None | Complete |

| Caudal | None | None | None | Ameloblastoma | N/A | Complete |

| Segmental | Bilateral M/R | None | None | Melanoma | None | Complete |

| TUM | M/R | None | Mild swelling | SCC | + | Incomplete |

| TUM | M/R | None | Mild swelling | Melanoma | + | Complete |

- Abbreviations: TUM, total unilateral mandibulectomy; M, mandibular; R, retropharyngeal; OSA, osteosarcoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; FSA, fibrosarcoma.

3.2 Intraoperative complications

Significant haemorrhage occurred in one patient after accidental damage to the maxillary portion of the mandibular artery during disarticulation of the TMJ. The torn vessel was identified and ligated. The animal received a blood transfusion and recovered uneventfully.

3.3 Postoperative evaluation/complications

Evaluation of the patients on the next morning revealed mild/moderate ventral oedema surrounding the caudal aspect of the incision in all patients. The oedema seemed to be more severe patients that had received bilateral removal of both mandibular and retropharyngeal lymph nodes. In two patients that received a total unilateral mandibulectomy, an ipsilateral sublingual swelling was observed. Such swelling resolved spontaneously in both patients within the next 7 days. Appetite and attitude were considered normal, and all the patients were discharged within 24 to 48 hours of the surgery. Discharge instructions included to continue icing the incision for two additional days (20 minutes, three times daily), use of the Elizabethan collar at all times for 14 days, exercise restriction for 14 days and soft food for 4 weeks. Medications prescribed included tramadol (Amneal Pharmaceuticals of NY, Hauppauge, NY; 2-3 mg/kg, orally every 8-12 hours, for 3-5 days) and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs at the discretion of the attending surgeon. Additional follow-up with the owners confirmed normal appetite and attitude and resolution of the ventral cervical swelling within 5 days of the surgery.

4 DISCUSSION

Our results indicate the ventral mandibulectomy technique is well tolerated and associated with acceptable morbidity. The visualization of important anatomic structures, such as the inferior alveolar artery and the TMJ decreases the chance of severe haemorrhage. Blood loss is one of the most common intra-operative complications of mandibulectomy.8, 9 In our series, one dog had severe haemorrhage because of accidental severing of the mandibular portion of the maxillary artery during disarticulation. Such trauma can be avoided by precise identification and disarticulation of the joint. The mandibular portion of the maxillary artery crosses from lateral to medial and immediately caudal to the TMJ.6 The ventral approach for unilateral total mandibulectomy compares favourably to the lateral approach because of the fact that incision on the lip commissure is not necessary. This prevents incision on branches of the facial artery and vein. When performing a caudal mandibulectomy, osteotomy of the zygomatic is also not necessary. Such approach has been described to allow better visualization and removal of the ramus of the mandible.4 This also decreases the morbidity of the current procedure in addition to saving time required to replace the zygomatic arch and wire it.4 In comparison to the intra oral approach, we believe the herein described technique compares favourably in both visualization of the important anatomic structures mentioned above as well as facilitating en bloc resection of the mandible. In our technique, we believe the surgeon has more control over cutting the muscles on the deep and lateral margins around the tumour. Unfortunately, the two techniques described previously (Withrow et al and Harvey) were never compared. Harvey reported the results of mandibulectomy in dogs, but in that report, multiple studies were used to compile his results. Such results from various authors revealed that greater than 50% (42/80 patients) of animals reported died or were euthanized because of local tumour progression.10 It was not possible nor was the intent of our study to directly compare techniques for mandibulectomy. We believe, one of the reasons complete margins was achieved in the majority of our patients was, at least in part, a result of better surgical planning allowed by performing a pre-operative computed tomography.

One perceived disadvantage of the ventral mandibulectomy approach when compared with the intra-oral approach is that in the former a skin incision is not performed, which is ideal in cases the skin is not affected. Follow-up with the cases in our series did not reveal local recurrence. In addition, the authors believe our approach facilitates en bloc resection in comparison to the intraoral approach.

One final potential advantage of the ventral approach can be seen when performing a caudal mandibulectomy without disarticulation of the TMJ. In such case, the distance between the angular process and condylar process has to be such to allow the saw blade to be angled in a way to cut the ramus while preserving the condylar process, TMJ and a significant portion of the ramus. The authors recall performing such a procedure in only one (large) dog.

The authors in this study often perform bilateral mandibular and retropharyngeal lymph node removal for highly metastatic cancers of the oral cavity, such as melanoma. An additional advantage in the ventral mandibulectomy approach is that dissection of these lymph nodes is easily achieved by caudal extension of the incision without the need to reposition the patient.7 The importance of bilateral lymphadenectomy in cases of head cancer is underscored by a recent study, which showed that 62% of the cases of lymph node metastasis were contralateral to the side of the primary tumour.11 The technique performed in our cases is similar to what has been described by Green and Boston.7 Transient self-limiting ventral cervical swelling is to be expected after bilateral removal of mandibular and retropharyngeal lymph nodes, but a significant clinical problem was not observed in our series of cases. Regional lymph node removal can add valuable information to clinical staging of oral cancer although the effect of removal in disease control and survival has not been properly established. In theory, reducing the tumour volume by removing affected lymph nodes could have an impact on survival. Regional lymph node removal has been evaluated in mast cell tumours and anal sac apocrine gland adenocarcinoma and in both tumours a survival influence has been observed.11-14

Sublingual swelling (ranula-like lesions) was observed in two cases and in both these cases spontaneous resolution occurred within 5 days. The occurrence of the sublingual swelling has been reported as a complication of mandibulectomy. In our series of cases, oedema of the surrounding tissues and temporary obstruction of the salivary duct was likely the cause of the sialocele because of the spontaneous resolution.4, 9, 15, 16

In conclusion, we believe the ventral approach to the mandible should be considered as an alternative for caudal and unilateral mandibulectomy in dogs. It allows easy identification of the most important structures in the area and can be performed with acceptable intra-operative and postoperative complications. Finally, it facilitates removal of the mandibular and retropharyngeal lymph nodes either for purposes of staging or as part of the treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. Richard AS White for generating the idea about this procedure.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.