Exporting creative and cultural products: Birthplace diversity matters!

Abstract

This paper analyses the effect of birthplace diversity on exports of creative and cultural goods, for 19 OECD countries, over the period 1990–2010. By matching UNESCO's creative and cultural exports classification to trade and migration data, we find a strong positive effect of birthplace diversity on the export of creative products. In particular, a 10% increase in the birthplace diversity index implies a 4% increase in creative goods exports. These results are robust across several specifications and shed light on a potential new channel through which migrants can contribute to the host country's export performance. It is interesting to note that only diversity of secondary and tertiary educated immigrants contributes to an increase in exports of creative and cultural goods. An instrumental variables approach addresses the potential endogeneity problems and confirms our results.

1 INTRODUCTION

By showing that birthplace diversity has a positive and significant effect on the economic prosperity (per capita GDP) of host countries, the work of Alesina, Harnoss, and Rapoport (2016) triggered renewed interest from scholars in understanding the economic consequences of cultural diversity. The present paper, which is in the spirit of Alesina et al. (2016), analyses the effect of birthplace diversity on a specific component of rich countries’ economic development: the exports of cultural and creative products.

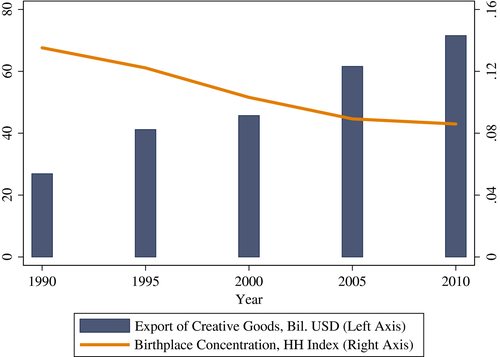

In many developed countries, the cultural and creative industries account for an important share of total GDP and employment. According to a recent report by Tera Consultants (2014), in 2011 creative and cultural industries (core and non-core)1 represented 6.8% of total GDP and 6.5% of total employment in Europe. A closer look at specific EU members reveals that, for some countries, the creative and cultural industries are even more important. For example, in 2011, the UK creative and cultural industries accounted for 9% of total GDP and employment. Similarly, in France, these industries accounted for 7.9% of total GDP and 6.3% of total employment in 2011. Thus, the creative and cultural industries play a crucial role in the economic development of wealthy countries. This is reflected in the pattern of increasing exports of creative and cultural products since the mid 1990s by the OECD countries. Figure 1 depicts total exports of creative goods for the sample of 19 OECD countries analysed in this paper and shows a clear positive pattern over time. Therefore, understanding the determinants of creative and cultural goods exports should be of prime interest to policymakers in developed countries.

Exports of creative goods and Herfindahl-Hirschman (HH) index of immigrants’ birthplace: OECD countries, 1990–2010

Note: The blue bars report the total amount of exports in cultural and creative goods for the full sample of exporting countries in our data. The red line refers to the average HH index of immigrants’ birthplace across exporting countries.

Source: Authors’ calculation on BACI and IAB data. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

This paper analyses the role of diversity in the birthplaces of foreign-born individuals in trade in creative and cultural goods.2 People originating from different countries bring to their destination countries diverse skills, culture, value systems and problem-solving capabilities, which are crucial assets in the industry of creative and cultural goods. So, as suggested by Florida (2002), the implication for destination countries of diversity in the birthplace of immigrants is a more diverse distribution of worker types and thus the presence of very talented workers and the burgeoning (or strengthening) of their innovative and creative industries.3 More formally, Lazear (1999, p. 16) proposes a model in which the cost of diversity in production teams (i.e., coordination costs) might be over-compensated by production complementarities: “Disjoint and relevant skills create an environment where the gains from complementarities can be significant.” In the same vein, Hong and Page (2001) demonstrate, theoretically, that a team of cognitively diverse individuals with limited abilities may perform better than a group of highly able, cognitively homogeneous individuals. Moreover, Maggi and Grossman (2000) develop a model in which the distribution of worker types (i.e., concentration/diversification of abilities in the country) matters for that country's comparative advantage and export performance. In particular, countries with a more diverse population will export goods produced using technologies characterised by high substitutability among employees, in which case, the presence of highly talented workers is extremely important. Creative products belong to this category. Since highly talented workers are relatively more present in more diverse countries (i.e., fat-tailed distribution of capabilities), these countries have comparative advantage in exporting creative products. This is the idea underlying the empirical exercise conducted in the present paper.

Previous empirical evidence suggests a positive effect of diversity on the performance of groups of individuals. Hoogendoorn and van Praag (2012) set a randomised field experiment and find that more ethnically diverse teams show better performance than less diverse teams. In more diverse teams, the coordination costs resulting from this diversity are offset by the pool of available relevant knowledge (skills), which facilitates (mutual) learning within ethnically diverse teams. Kahane, Longley, and Simmons (2013) analyse data on the ethnic composition of National Hockey League teams in the US and find that more diverse teams (with a high share of European players) demonstrate better performance. According to Kahane et al. (2013), the “productivity” premium provided by diverse teams lies in the skill effect (selection of best foreign players) and the complementarity between native and foreign-born players’ skills.4 See Horwitz and Horwitz (2007) for a meta-study of the effect of diversity on team performance. In addition, diversity has a positive effect of the productivity of cities and firms. Ottaviano and Peri (2006) find that a more multicultural urban environment increases the productivity of US-born citizens. Trax, Brunow, and Suedekum (2015) use German establishment level data to analyse the micro and the macrolevel effects of diversity on productivity. The authors find that both the diverseness of foreign-born workers and the spillover from regional diversification increase the productivity of plants.

By testing the effect of diversity on the export of creative goods, we contribute also to the long debate on the effect of migration on exports. The literature on the trade-migration nexus suggests a strong positive effect of immigrants on the export performance of host countries. Migrant communities’ business and social networks promote the export activity of host countries by reducing information costs and boosting the diffusion of preferences (Head & Ries, 1998; Rauch, 2001). Migrants, especially highly skilled individuals, help domestic firms in overcoming the cultural barriers to trade (language, local tastes, etc.) and creating international business relationships (Combes, Lafourcade, & Mayer, 2005; Herander & Saavedra, 2005; Rauch & Trindade, 2002).

We complement the broad literature on birthplace diversity and economic performance, and add a new channel to the trade-migration nexus literature. The present paper provides two main contributions. First, we uncover a new channel through which diversity can affect national prosperity, that is, by affecting exports of creative and cultural products. Second, we make progress in addressing the endogeneity of migrants by providing an adjusted version of the shift-share instrumental variable proposed by Card (2001).

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2 discusses the index of birthplace concentration used in the paper. Section 3 presents our empirical strategy, the data used to conduct the empirical exercise and how we address the problem of endogeneity. Section 4 presents the results, and Section 5 concludes the paper.

2 HERFINDAHL-HIRSCHMAN INDEX TO MEASURE THE BIRTHPLACE DIVERSITY

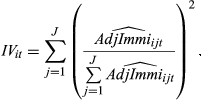

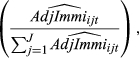

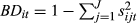

(1)

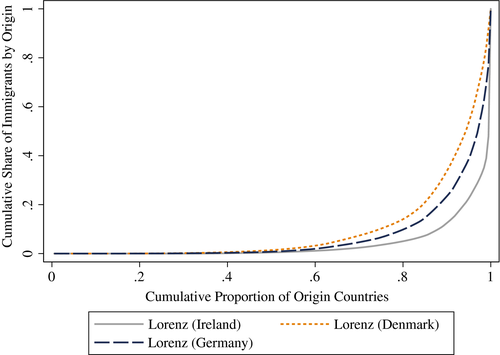

(1)

Source: Authors’ calculation on IAB data. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Notice that our measure of birthplace diversity is similar to that adopted in Alesina et al. (2016) and Trax et al. (2015). These works use an index that directly measures diversity in the birthplace of immigrants (i.e., 1 minus the HH index).5 In our baseline regressions, we include the HH index as an inverse measure of diversity (see Equation 1), and we provide robustness checks using the same birthplace diversity index as in Alesina et al. (2016) to show that our results are robust to a direct or indirect measure of birthplace diversity.6

3 EMPIRICAL STRATEGY

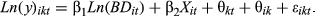

(2)

(2)The subscripts i, k and t denote, respectively, exporting country, HS 2-digit sector and year. The dependent variable yikt is the creative and cultural exports of country i, sector s, time t. To keep the zeros after the log transformation, we simply impose that the Ln(y)ikt is equal to zero when yikt is zero. Notice that the number of zeros in the data is greatly reduced (0.42%) because we have country-sector-specific data only for rich countries (not using bilateral trade data reduces concerns about zero trade flows). However, we also use a PPML estimation, as proposed by Silva and Tenreyro (2006), to control for possible heteroscedasticity in the trade data. In the PPML estimations, we use creative products exports in levels rather than in log.

The main explanatory variable is the log of the birthplace diversity index BDit as defined in Section 2. The set of control variables Xit includes the following: (i) the log of total exports of country i in sector k to control for the overall export dynamics of the country-sector; (ii) the number of countries of origin for migrants residing in country i; (iii) the country's total population, to control for the size effect on exports (as in Alesina et al., 2016); and (iv) the share of natives in the country's total population. Including the share of natives in the total population is important since it controls for the size effect of migration. It allows us to disentangle size from the fractionalisation (diversity) of immigrants in the destination country—as in Alesina et al. (2016) and Trax et al. (2015). Including the share of natives allows us to test whether there is any direct effect of the foreign-born population on the export of creative goods. If the theoretical discussion in the introduction holds, we expect a null coefficient for the share of natives. What matters for export performance in creative products is the diversity of cultures and not the total number of immigrants.8 In a robustness check, reported in the appendix, we include per capita GDP as an additional covariate to control for the exporting country's income level.9

Any sector-specific shock affecting the export of creative products in a given year (i.e., productivity shock, sector-specific innovation, technological improvement) is captured by the sector-year fixed effects, θkt, included in all the estimations. The inclusion of country-sector fixed effects, θik, allows us to control for any country-sector-specific variable affecting the export of creative goods (i.e., sector comparative advantage, average level of development of the country, average expenditure in research and development in a country). The inclusion of country-sector fixed effects implies that our results should be interpreted in deviations from the country-sector mean (within estimator). The dependent variable (export of creative products) is country-sector-year specific; our main explanatory variable is country-year specific. For this reason, standard errors are clustered by country-year in all the estimations.

3.1 Endogeneity

A potential issue that needs to be addressed is endogeneity. Omitted variables concerns are reduced in our case since we include country-sector fixed effects which capture all unobserved destination-specific factors affecting the settlement of immigrants in the host countries (i.e., average income level, immigration policy and any country-specific economic factor attracting immigrants). However, an unobserved country-year-specific shock might contemporaneously affect the exports of creative goods and the settlement of immigrants across destinations. Moreover, reverse causality could produce biased ordinary least squares (OLS) estimations if changes in the export of creative goods affect the demand for labour in the country and, in particular, demand for high-skilled (immigrant) workers. We address these endogeneity concerns by adopting an instrumental variable approach (two-stage least squares—2SLS).

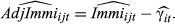

(3)

(3) (fit of the regression) from which we exclude the destination-year fixed effect component:

(fit of the regression) from which we exclude the destination-year fixed effect component:

(4)

(4) :

:

(5)

(5)

As a robustness check, we use the 5-year lag of the BD index as an instrumental variable, which allows us to test an overidentified model and to apply a Sargan test for validity of the instrumental variables. The idea is that the composition of the migrant population is persistent over time, so the lagged value of the diversity index is a good proxy for the current diversity index value (relevant IV). Moreover, any contemporaneous shock to creative products exports cannot be related to previous values of the diversity index (IV validity).

3.2 Data and Descriptive evidence

Our calculation of the BD index relies on IAB bilateral migration stocks data. IAB data include information on migrants’ country of origin (nationality) and education level for 20 OECD destination countries, during the period 1980–2010 (5-year intervals). Data on the education level of immigrants (primary, secondary, tertiary) allow us to test the effect of birthplace diversity by skill level.13 To calculate the concentration index, we consider migrants as foreign-born individuals aged at least 25 years. A potential drawback of using IAB data is that they report only the nationalities. Naturalised foreign-born individuals and second-generation immigrants are not classified as “immigrant” in our data. So, our measure of birthplace concentration underestimates the real degree of cultural diversity.

As a robustness check, we use bilateral migration flows rather than stocks to compute the concentration index. In this case, we rely on the data in Abel and Sander (2014), which provide information on bilateral migration flows for a 178×178 matrix of origin–destination combinations, for the years 1995, 2000, 2005 and 2010.14 Bilateral migration stocks (and flows) are used to compute a country-year-specific birthplace diversity measure (see Equation 1) that can be merged with data on creative and cultural goods exports.

To calculate the volume of creative and cultural goods exports, we combine trade data from BACI (CEPII) with three recent HS-based classifications of creative and cultural goods. The first classification was released by UNESCO and includes only the core creative industries (used here as baseline). The second was also released by UNESCO and includes both core and non-core creative industries (robustness check). The third classification used in this paper was released by UNCTAD (robustness check). Trade data from BACI provide information on the value of export flows (in US$) for a complete set of exporting and importing countries in the period 1989–2015, by product HS 6-digit level. Then, the UNESCO (and UNCTAD) classification is used to identify whether a specific HS 6-digit code belongs to the category “creative and cultural exports.” This allows us to compute the total amounts of creative and cultural goods exports by country-sector(HS2)-year, which we use as the main dependent variable in our empirical exercise. Notice that, in our regression sample, we include only the HS 2-digit sectors containing at least one HS 6-digit product classified as “creative or cultural.”

Merging trade data on cultural products (UNESCO core classification) with the BD index based on the stock of migrants (baseline estimations) produces a sample of 1,425 observations: 19 exporting countries,15 15 HS 2-digit sectors, and 5 years (1990, 1995, 2000, 2005 and 2010). See Table 1 panel A for in-sample descriptive statistics. When we use the UNESCO (core plus non-core) classification, the number of observations increases slightly (1,615 observations) because two additional HS 2-digit sectors include non-core creative products (see Table 1 panel B). When we use the UNCTAD classification for creative goods, the number of observations increases because it includes 29 HS 2-digit chapters with creative products. See Table 1 panel C for in-sample descriptive statistics using the UNCTAD classification to define creative products. Importantly, our results are robust to the three classifications used to define creative exports. In contrast, if we merge trade data with the BD index based on flows of migrants (robustness check), the number of observations increases since the sample of exporting countries is larger (178 exporting countries).

| Obs | Mean | Std Dev | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A | UNESCO core classification | ||

| Exports creative (log) | 1,425 | 9.01 | 2.91 |

| Birthplace diversity (log of HH) | 1,425 | −2.46 | 0.60 |

| Tot exports (log) | 1,425 | 12.25 | 2.37 |

| Population (log) | 1,425 | 16.56 | 1.16 |

| Num. of origins | 1,425 | 157.34 | 39.02 |

| Share of natives | 1,425 | 0.91 | 0.05 |

| Panel B | UNESCO classification | ||

| Exports creative (log) | 1,615 | 9.69 | 3.11 |

| Birthplace diversity (log of HH) | 1,615 | −2.46 | 0.60 |

| Tot exports (log) | 1,615 | 12.58 | 2.51 |

| Population (log) | 1,615 | 16.56 | 1.16 |

| Num. of origins | 1,615 | 157.35 | 39.02 |

| Share of natives | 1,615 | 0.91 | 0.05 |

| Panel C | UNCTAD classification | ||

| Exports creative (log) | 2,755 | 9.25 | 2.70 |

| Birthplace diversity (log of HH) | 2,755 | −2.46 | 0.60 |

| Tot exports (log) | 2,755 | 11.86 | 2.57 |

| Population (log) | 2,755 | 16.57 | 1.16 |

| Num. of origins | 2,755 | 157.35 | 39.02 |

| Share of natives | 2,755 | 0.91 | 0.05 |

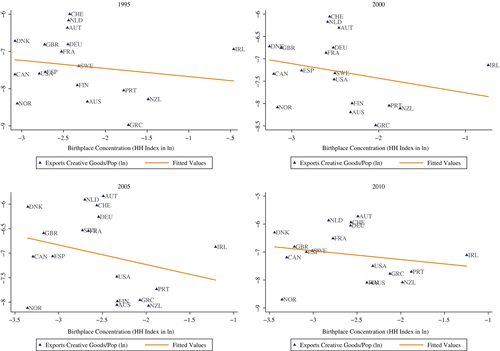

Figure 3 depicts the simple correlations between countries’ exports of creative products (country averages across sectors), conditioned on the size of the country and the diversity of immigrants’ birthplaces (HH index). For the years 1995, 2000, 2005 and 2010, the relation is always negative, suggesting a positive correlation between the export of creative products and diversity in immigrants’ birthplaces.

Source: Authors’ calculation on BACI and IAB. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

4 RESULTS

4.1 Baseline results

Ordinary least squares results for Equation 2 are presented in Table 2. Across all specifications, the concentration of immigrant birthplaces has a negative and significant effect on the export of creative and cultural goods. This means that immigrant diversity has a positive impact on the creative goods exports. In particular, using our preferred specification (column (3)), a 10% decrease in the birthplace concentration index implies a 4% boost in the export of creative and cultural goods. Notice that our results hold for both the UNESCO and the UNCTAD classifications of creative and cultural goods (see columns (3)–(5)). As expected, the share of natives in the total population has no effect on the export of creative products, confirming the idea that it is the diversity in immigrants’ origins that matters for the export of creative goods, not the size of the foreign-born population. Our baseline results are robust to the inclusion of per capita GDP among the covariates. See Appendix Table A1.

| Dep var: | Exports of creative products (in log) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Birthplace diversity (log of HH) | −0.343** | −0.392*** | −0.392*** | −0.284** | −0.246** |

| (0.145) | (0.133) | (0.135) | (0.111) | (0.095) | |

| Tot exports (log) | 0.770*** | 0.766*** | 0.766*** | 0.839*** | 0.825*** |

| (0.061) | (0.064) | (0.064) | (0.044) | (0.047) | |

| Population (log) | −1.154 | −1.110 | −1.112 | −0.992* | −1.096** |

| (0.728) | (0.697) | (0.698) | (0.588) | (0.544) | |

| Number of origins | −0.002 | −0.002 | −0.002* | −0.002 | |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.002) | ||

| Share of natives | −0.022 | −1.231 | 0.137 | ||

| (2.121) | (1.801) | (1.475) | |||

| Product classification | UNESCO | UNESCO | UNESCO | UNESCO | UNCTAD |

| Core | Core | Core | |||

| Country-sector FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sector-year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 1,425 | 1,425 | 1,425 | 1,615 | 2,755 |

| R 2 | .967 | .967 | .967 | .980 | .971 |

Notes

- Herfindahl-Hirschman (HH) index is an inverse measure of diversity. A negative coefficient suggests a positive relationship between birthplace diversity and export of creative goods. Standard errors are clustered by country-year.

- ***p < .01; **p < .05; *p < .1.

Table 3 presents the results of the 2SLS using the instrumental variables described in Section 3.1. Column (1) presents the estimation results using the IV based on the predicted supply-driven migration stocks and, column (2) presents the results using a 5-year lag of the BD index as an instrumental variable. In columns ((3)–(5)), we employ an overidentified model and put both IVs in the first stage. The relevance of the two IVs is suggested by the first-stage coefficients at the bottom of the table. In all the specifications, the instruments are good proxies for the (potential) endogenous BD index. The first-stage F-stat are all considerably above the rule of thumb value of 10 and remove any potential problem of weak instruments. The Sargan tests presented in columns ((3)–(5)) prove the validity of our IVs (orthogonality). Finally, to support the exclusion restriction of our IVs (as suggested by Conley, Hansen, & Rossi, 2012), we estimate Equation 2 by adding the two IVs (separately, and then together) as additional covariates to test whether they have a direct effect on the export of creative goods. The exclusion restriction assumption is satisfied if the IVs affect the export of creative goods only through their influence on the endogenous regressor (and, thus, when they have no direct effect on the export of creative goods). As expected, none of the IVs has a significant direct effect on the export of creative goods, supporting the validity of the exclusion restriction (see Table A2). The second-stage results of the 2SLS approach are reported at the top of Table 3 and confirm what discussed above. Diversity in the birthplace of immigrants has a positive and significant effect on the export of creative goods (no matter which classification is used to identify creative products). In particular, a 10% decrease in the BD index (i.e., an increase in birthplace diversity) implies a 4.4% increase in the export of creative products—see column (3) in Table 3.

| Dep var: | Exports of creative products (in log) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Birthplace diversity (log of HH) | −0.533** | −0.397** | −0.436** | −0.379** | −0.346*** |

| (0.256) | (0.176) | (0.171) | (0.167) | (0.128) | |

| Tot exports (log) | 0.765*** | 0.766*** | 0.766*** | 0.837*** | 0.823*** |

| (0.064) | (0.064) | (0.064) | (0.044) | (0.048) | |

| Population (log) | −1.133 | −1.113 | −1.118 | −1.005* | −1.109* |

| (0.701) | (0.697) | (0.697) | (0.591) | (0.560) | |

| Number of origins | −0.003 | −0.002 | −0.002 | −0.003* | −0.002 |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.002) | |

| Share of natives | 0.342 | −0.010 | 0.090 | −0.987 | 0.394 |

| (2.219) | (2.219) | (2.203) | (1.896) | (1.551) | |

| Product classification | UNESCO | UNESCO | UNESCO | UNESCO | UNCTAD |

| Core | Core | Core | |||

| Country-sector FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sector-year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| IV: BD based on imputed immigrants | 0.791*** | 0.379*** | 0.379*** | 0.375*** | |

| IV: 5-year lag BD | 0.693*** | 0.550*** | 0.550*** | 0.549*** | |

| F-test | 26.59 | 73.42 | 75.58 | 75.94 | 75.59 |

| Hansen J | 0.480 | 0.523 | 0.251 | ||

| Observations | 1,425 | 1,425 | 1,425 | 1,615 | 2,755 |

| R 2 | .967 | .967 | .967 | .980 | .971 |

- Herfindahl-Hirschman (HH) index is an inverse measure of diversity. A negative coefficient suggests a positive relationship between birthplace diversity and export of creative goods. Standard errors are clustered by country-year.

- ***p < .01; **p < .05; *p < .1.

Table 4 presents our first robustness check using a PPML estimator to address the zero trade flow problem. Our results perfectly hold when we use the UNESCO classification (both core and core plus non-core classifications)—see columns (1) and (2). The sign of the coefficient is in line with expectations for the UNCTAD classification also, but is estimated with errors (coefficient not significantly different from zero).

| Dep var: | Exports of creative products | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Birthplace diversity (log of HH) | −0.144*** | −0.252*** | −0.018 |

| (0.046) | (0.080) | (0.031) | |

| Tot exports (log) | 0.821*** | 1.085*** | 0.909*** |

| (0.055) | (0.066) | (0.031) | |

| Population (log) | −0.341 | 0.063 | −0.711** |

| (0.430) | (0.790) | (0.287) | |

| Number of origins | −0.002** | 0.001 | −0.001*** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.000) | |

| Share of natives | −2.490* | −1.291 | 0.239 |

| (1.512) | (2.007) | (0.932) | |

| Product classification | UNESCO | UNESCO | UNCTAD |

| Core | |||

| Country-sector FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sector-year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 1,425 | 1,615 | 2,755 |

| R 2 | .989 | .986 | .991 |

- Herfindahl-Hirschman (HH) index is an inverse measure of diversity. A negative coefficient suggests a positive relationship between birthplace diversity and export of creative goods. Standard errors are clustered by country-year.

- ***p < .01; **p < .05; *p < .1.

Table 5 presents another robustness check using the alternative definition of birthplace diversity proposed by Alesina et al. (2016) —one minus the HH index applied to the population of immigrants. The results are qualitatively similar to those obtained using our BD index, but have the opposite signs (the measure proposed by Alesina et al. (2016) is a direct measure of diversity). Appendix Table A3 presents the 2SLS results using the birthplace diversity index, as in Alesina et al. (2016). As in our baseline estimations, we use two instrumental variables: (i) the diversity index (1-HH) based on the supply-driven predicted migration stocks, and (ii) a 5-year lag of the diversity index (1-HH). In all the specifications (for the three classifications of creative goods), an increase in birthplace diversity index boosts the export of creative goods.16

| Dep var: | Exports of creative products (in log) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Birthplace diversity (1-HH) | 1.496* | 2.477*** | 2.506*** | 1.774*** | 1.574*** |

| (0.845) | (0.808) | (0.839) | (0.671) | (0.586) | |

| Tot exports (log) | 0.758*** | 0.739*** | 0.740*** | 0.820*** | 0.814*** |

| (0.062) | (0.062) | (0.061) | (0.045) | (0.042) | |

| Population (log) | −1.708** | −2.034*** | −2.011*** | −1.623** | −1.654*** |

| (0.770) | (0.711) | (0.709) | (0.634) | (0.534) | |

| Number of origins | −0.005*** | −0.005*** | −0.004*** | −0.003*** | |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | ||

| Share of natives | 0.437 | −0.925 | 0.488 | ||

| (2.038) | (1.692) | (1.466) | |||

| Product classification | UNESCO | UNESCO | UNESCO | UNESCO | UNCTAD |

| Core | Core | Core | |||

| Country-sector FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sector-year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 1,425 | 1,425 | 1,425 | 1,615 | 2,755 |

| R 2 | .967 | .968 | .968 | .981 | .971 |

- Standard errors are clustered by country-year.

- ***p < .01; **p < .05; *p < .1.

4.2 Robustness check using migration flows

The main drawback to IAB data on bilateral migration stocks is the small sample of destination countries (19 OECD countries), which implies the validity of the diversity-creative export nexus for the subsample of rich countries only. In this section, we account for this limitation by increasing the set of destination (exporting) countries using Abel and Sander (2014) data on bilateral migration flows to/from 178 countries. The construction of the BD index does not change; we simply apply Equation 1 to an alternative migration data set including a bigger sample of destination countries.

The results of this robustness check are reported in Table 6 and show that, even if we consider a bigger set of exporting countries (both developed and developing), the positive effect of birthplace diversity on the export of creative goods holds, but the coefficient is smaller, indicating that the inclusion of poor countries weakens the nexus. This suggests that the effect of birthplace diversity for boosting exports of creative goods is particularly important for developed countries.

| Dep var: | Exports of creative products (in log) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Birthplace diversity (log of HH) | −0.080** | −0.092** | −0.092** | −0.109*** | −0.089** | −0.081** |

| (0.035) | (0.041) | (0.041) | (0.042) | (0.036) | (0.033) | |

| Tot exports (log) | 0.455*** | 0.455*** | 0.455*** | 0.456*** | 0.542*** | 0.520*** |

| (0.020) | (0.020) | (0.020) | (0.020) | (0.018) | (0.016) | |

| Population (log) | −0.298 | −0.304 | −0.304 | −0.569** | −0.431* | −0.207 |

| (0.337) | (0.345) | (0.345) | (0.277) | (0.251) | (0.229) | |

| Number of origins | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.002 | −0.001 | −0.001 | |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | ||

| Share of natives | −1.952** | −0.968 | −1.408** | |||

| (0.897) | (0.828) | (0.701) | ||||

| Product classification | UNESCO | UNESCO | UNESCO | UNESCO | UNESCO | UNCTAD |

| Core | Core | Core | Core | |||

| Country-sector FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sector-year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 9,608 | 9,608 | 9,608 | 9,608 | 11,764 | 20,068 |

| R 2 | .943 | .943 | .943 | .943 | .954 | .954 |

- Herfindahl-Hirschman (HH) index is an inverse measure of diversity. A negative coefficient suggests a positive relationship between birthplace diversity and export of creative goods. Standard errors are clustered by country-year.

- ***p < .01; **p < .05; *p < .1.

4.3 Results by skill level

As discussed in the introduction, the diversity and export of creative goods nexus is supposed to be particularly strong for the most talented workers (see Florida, 2002). The biggest contribution to the “creative” process in the creative and cultural goods industry is supposed to be generated by tertiary educated individuals. So, we expect diversity among high-skilled immigrants to have the strongest effect on the export of creative goods. We exploit information on immigrants’ education level from IAB and compute the BD index (as in Equation 1) by education level. The baseline specification results by education level are reported in Table 7. We find negative and significant coefficient for the concentration of tertiary and secondary educated migrants, confirming the intuition that what matters for the export of creative goods is the diversity in the group of the most talented workers. Moreover, in line with the intuition, the coefficient of tertiary educated is bigger than the coefficient of secondary educated immigrants.

| Dep var: | Exports of creative products (in log) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Birthplace diversity high skilled (log of HH) | −0.403*** | −0.221* | ||||

| (0.138) | (0.113) | |||||

| Birthplace diversity medium skilled (log of HH) | −0.221** | −0.172** | ||||

| (0.108) | (0.079) | |||||

| Birthplace diversity low skilled (log of HH) | −0.118 | −0.106 | ||||

| (0.116) | (0.092) | |||||

| Tot exports (log) | 0.767*** | 0.766*** | 0.773*** | 0.827*** | 0.825*** | 0.830*** |

| (0.064) | (0.065) | (0.063) | (0.048) | (0.047) | (0.047) | |

| Population (log) | −0.853 | −1.022 | −1.160 | −0.950* | −1.034* | −1.158** |

| (0.677) | (0.717) | (0.744) | (0.571) | (0.549) | (0.529) | |

| Number of origins | −0.003 | −0.002 | −0.002 | −0.002 | −0.002 | −0.001 |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Share of natives | 1.200 | −0.345 | −0.799 | 0.727 | 0.044 | −0.294 |

| (2.243) | (2.177) | (2.230) | (1.607) | (1.493) | (1.584) | |

| Product classification | UNCTAD | UNCTAD | UNCTAD | UNCTAD | UNCTAD | UNCTAD |

| Core | Core | Core | ||||

| Country-sector FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sector-year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 1,425 | 1,425 | 1,425 | 2,755 | 2,755 | 2,755 |

| R 2 | .967 | .967 | .967 | .971 | .971 | .971 |

- Herfindahl-Hirschman (HH) index is an inverse measure of diversity. A negative coefficient suggests a positive relationship between birthplace diversity and export of creative goods. Standard errors are clustered by country-year.

- ***p < .01; **p < .05; *p < .1.

4.4 Results by macrosector

Finally, Table 8 reports the baseline estimation results by macrosector. Diversity in immigrants’ birthplaces may be of particular interest for some sectors and less relevant for others. While the estimated specification does not change (see Equation 2), we needed to adapt the set of fixed effects included in the regression to achieve sufficient variability in the data to identify the coefficient of interest. Therefore, we include only country and year fixed effects in the sector-specific regressions. Interestingly, the strongest contribution of birthplace diversity in boosting the export of creative goods is in: (i) plastic and rubbers, (ii) wood and wood products; and (iii) miscellaneous. Notice that the miscellaneous macrosector includes HS chapters 90–97, that is, optical, photographic and cinematographic products, clocks and watches, musical instruments, toys and games, works of art.

| Sector | Coeff | Std Err | Obs | R 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemicals | −0.289 | (0.475) | 95 | .912 |

| Plastic/Rubbers | −1.110*** | (0.308) | 95 | .949 |

| Wood and wood products | −0.914** | (0.430) | 190 | .441 |

| Textiles | 0.510*** | (0.192) | 190 | .877 |

| Stone/glass | −0.842** | (0.342) | 285 | .512 |

| Metals | −0.361 | (0.297) | 95 | .959 |

| Machinery/electrical | −0.380 | (0.297) | 95 | .973 |

| Miscellaneous | −0.952*** | (0.244) | 380 | .403 |

- Results from sector-specific regressions having the log of creative exports as dependent variable and the same set of control variables as in Equation 2. Country and year fixed effects included in all regressions. Standard errors are clustered by country.

- ***p < .01; **p < .05; *p < .1.

5 CONCLUSION

This paper has proposed a new channel through which diversity in the birthplaces of immigrants can affect the economic performance of the host country. We used a sample of 19 OECD developed countries over the period 1995–2010 and found overwhelming evidence of a positive effect of immigrants’ birthplace diversity on the export of creative and cultural products. This holds in particular for highly skilled and medium-skilled immigrants.

More specifically, according to our preferred specification, a 10% increase in the diversity of immigrants (or a reduction in their concentration) increases creative goods exports by 4%. This result, along with the important role of the creative and cultural goods industry in developed countries, suggests the policy relevance of our paper. Attracting immigrants from a more diverse set of origin countries may be a way to boost exports of creative and cultural products, which are important for the economic prosperity of developed countries.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Farid Toubal and Massimiliano Bratti for comments and suggestions. However, the views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and also do not reflect those of the CEPII.

. See Alesina et al. (2016) equation (8).

. See Alesina et al. (2016) equation (8).

APPENDIX A

| Dep var: | Exports of creative products (in log) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Birthplace diversity (log of HH) | −0.345** | −0.386*** | −0.387*** | −0.287** | −0.234** |

| (0.141) | (0.134) | (0.136) | (0.111) | (0.101) | |

| Tot exports (log) | 0.771*** | 0.763*** | 0.763*** | 0.842*** | 0.819*** |

| (0.065) | (0.066) | (0.066) | (0.049) | (0.048) | |

| Population (log) | −1.132 | −1.200* | −1.195*** | −0.927 | −1.306*** |

| (0.713) | (0.703) | (0.704) | (0.663) | (0.600) | |

| Per Capita GDP | −0.012 | 0.049 | 0.051 | −0.040 | 0.131 |

| (0.214) | (0.213) | (0.217) | (0.188) | (0.172) | |

| Number of origins | −0.002 | −0.002 | −0.002*** | −0.002 | |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.001) | ||

| Share of natives | 0.107 | −1.331 | 0.498 | ||

| (2.142) | (1.822) | (1.457) | |||

| Product classification | UNESCO | UNESCO | UNESCO | UNESCO | UNCTAD |

| Core | Core | Core | |||

| Country-sector FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sector-year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 1,425 | 1,425 | 1,425 | 1,615 | 2,755 |

| R 2 | .967 | .967 | .967 | .980 | .971 |

- Herfindahl-Hirschman (HH) index is an inverse measure of diversity. A negative coefficient suggests a positive relationship between birthplace diversity and export of creative goods. Standard errors are clustered by country-year.

- ***p < .01; **p < .05; *p < .1.

| Dep var: | Exports of creative products (in log) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Birthplace diversity (log of HH) | −0.296** | −0.384 | −0.298 |

| (0.147) | (0.283) | (0.265) | |

| Tot exports (log) | 0.767*** | 0.766*** | 0.767*** |

| (0.063) | (0.065) | (0.064) | |

| Population (log) | −1.028 | −1.111 | −1.028 |

| (0.710) | (0.699) | (0.711) | |

| Number of origins | −0.002 | −0.002 | −0.002 |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Share of natives | −0.585 | −0.0124 | −0.588 |

| (2.144) | (2.194) | (2.257) | |

| IV 1: BD based on imputed immigrants | −0.188 | −0.188 | |

| (0.199) | (0.204) | ||

| IV 2: 5-year lag BD | −0.008 | 0.002 | |

| (0.252) | (0.255) | ||

| Country-sector FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sector-year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 1,425 | 1,425 | 1,425 |

| R 2 | .967 | .967 | .967 |

- Herfindahl-Hirschman (HH) index is an inverse measure of diversity. A negative coefficient suggests a positive relationship between birthplace diversity and export of creative goods.

- Standard errors are clustered by country-year.

- ***p < .01; **p < .05; *p < .1.

| Dep var: | Exports of creative products (in log) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Birthplace diversity (1-HH) | 2.616*** | 2.007*** | 1.470** |

| (0.742) | (0.666) | (0.616) | |

| Tot exports (log) | 0.739*** | 0.816*** | 0.815*** |

| (0.061) | (0.044) | (0.043) | |

| Population (log) | −2.053*** | −1.711*** | −1.615*** |

| (0.708) | (0.605) | (0.511) | |

| Number of origins | −0.005*** | −0.004*** | −0.003** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Share of natives | 0.502 | −0.789 | 0.423 |

| (2.125) | (1.789) | (1.558) | |

| Product classification | UNESCO | UNESCO | UNCTAD |

| Core | |||

| Country-sector FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sector-year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| IV: BD based on imputed immigrants | 0.475** | 0.477** | 0.460** |

| IV: 5-year lag BD | 0.613*** | 0.612*** | 0.616*** |

| F-test | 33.92 | 34.08 | 33.71 |

| Hansen J | 0.427 | 0.283 | 0.035 |

| Observations | 1,425 | 1,615 | 2,755 |

| R 2 | .968 | .981 | .971 |

- Standard errors are clustered by country-year.

- ***p < .01; **p < .05; *p < .1.

| Dep var: | Share of creative products | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| Birthplace diversity (log of HH) | −0.032** | −0.0484** | −0.0379** | −0.0513** | |||

| (0.015) | (0.0243) | (0.0169) | (0.0229) | ||||

| Birthplace diversity (1-HH) | 0.256** | 0.229*** | 0.190* | ||||

| (0.103) | (0.072) | (0.096) | |||||

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Product Classification | UNESCO | UNESCO | UNESCO | UNCTAD | UNESCO | UNESCO | UNCTAD |

| Core | Core | Core | |||||

| Country-sector FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sector-year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| IV: BD based on imputed immigrants | 0.385*** | 0.385*** | 0.385*** | 0.613*** | 0.612*** | 0.616*** | |

| IV: 5-year lag BD | 0.543*** | 0.543*** | 0.543*** | 0.475** | 0.477** | 0.460** | |

| F-test | 73.05 | 73.09 | 73.19 | 33.92 | 34.08 | 33.71 | |

| Hansen J | 0.374 | 0.940 | 0.253 | 0.0722 | 0.464 | 0.0160 | |

| Observations | 1,425 | 1,425 | 1,615 | 2,755 | 1,425 | 1,615 | 2,755 |

| R 2 | .956 | .956 | 0.977 | .954 | .956 | .977 | .954 |

- Standard errors are clustered by country-year.

- ***p < .01; **p < .05; *p < .1.