The true art of the tax deal: Evidence on aid flows and bilateral double tax agreements

Abstract

Of a total of 2,976 double tax agreements (DTAs), some 60% are signed between a developing and a developed economy. As DTAs shift taxing rights from capital-importing to capital-exporting countries, the latter inherently benefit more from the agreements. In this paper, we argue that capital exporters use foreign aid to incite capital importers into signing DTAs. We demonstrate in a theoretical model that in a deal, one country does not trump the other, but that the deal must be mutually beneficial. In the case of an asymmetric DTA, this requires compensation from the capital-exporting country to the capital-importing country. Examining DTAs that are signed between donor and recipient countries between 1991 and 2012, and using a fixed effects Poisson model, we find that bilateral foreign aid commitments increase by 22% in the year of the signature of a DTA. Evaluated at the sample mean, this translates into around US$ six million additional aid commitments in a DTA signatory year.

1 INTRODUCTION

With rising cross-border capital flows, the interaction of national tax jurisdictions has increasingly gained in relevance in the last decades. Given the lack of a unified global tax order and the so far limited scope of multilateral initiatives, the tax treatment of cross-border activities remains to a large degree regulated by bilateral double taxation agreements (DTAs).1 These agreements set tax rules and allocate taxing rights between the two signatory states.

Of the 2,976 DTAs in place as of 2010, some 500 DTAs covered relationships between OECD countries (17% of the total). About a third of the treaties were signed between two developing economies, and more than 50% were between a developing on the one hand and an OECD country on the other hand (Baker, 2014). This latter category, so-called asymmetric DTAs, is the focus of this paper.

The large majority of DTAs is drafted along either the OECD or the UN Model Tax Conventions (MTC) (Wijnen & de Goede, 2014). Both these conventions (albeit the UN Convention to a lesser degree) tend to shift taxing powers from the source state, that is, the state where income is generated, to the residence state of a company. For two countries with largely symmetric investment patterns, this imbalance is not problematic.

Conversely, when two countries with an asymmetric investment position sign such a DTA, this shifting of taxing powers inherently implies a loss of tax base for the capital-importing country (see, e.g., Rixen & Schwarz, 2009). With capital still flowing predominantly from industrialised to developing countries and capital income flowing the other way, such agreements may thus put capital-importing developing countries at a disadvantage.

This raises the question as to why capital-importing countries sign such DTAs. Several reasons have been brought forward. Most prominently, it has been argued that developing countries expect increased capital inflows after the signature of DTAs (e.g., Lang & Owens, 2014). Empirical evidence as to whether DTAs indeed lead to higher investment flows is, however, far from conclusive (see, e.g., Baker, 2014). From a policy perspective, Pickering (2013) argues that capital-exporting countries have a higher bargaining power and thus can pressure capital importers into signing DTAs.

In this paper, we propose a further explanation. We argue that capital exporters use foreign aid to incite capital importers into signing DTAs. We claim that capital importers who sign a DTA are compensated through official development assistance (ODA). We regard this not as an alternative but as an additional mechanism to explain the signing of DTAs between countries with unbalanced investment patterns.

The strategic use of ODA as a foreign policy instrument has been documented in various contexts. Alesina and Dollar (2000) argue that the allocation of foreign aid can—to a large extent—be explained by political and strategic factors. They find a positive association between the amounts of bilateral aid a country receives and its alignment with the respective donor country's voting behaviour at the UN General Assembly. Kuziemko and Werker (2006) find that US and UN aid flows to the rotating members of the United Nations Security Council rise significantly during the 2-year period of their Security Council membership. The authors argue that the patterns found are best explained through strategic vote buying. In addition, temporary members of the United Nations Security Council are found to benefit from more programmes from the International Monetary Fund (and from programmes with more favourable conditions) (Dreher, Sturm, & Vreeland, 2009b). Further, Dippel (2015) provides evidence of the strategic use of ODA by major donors to influence or reward voting behaviour in the International Whaling Organization.

Similarly, analysing the political economy of aid in donor and recipient countries theoretically and empirically, de Mesquita and Smith (2009) conclude that OECD countries’ bilateral giving is only to a small degree motivated by humanitarian motives. Faye and Niehaus (2012) find that in election years, donors try to actively influence election outcomes in recipient countries by disbursing additional aid to closely aligned governments. Using data on World Bank lending, Kersting and Kilby (2016) find evidence of global electioneering that specifically serves US foreign policy interests.

Empirical evidence thus illustrates that besides the humanitarian needs of recipient countries, also strategic interests of donor countries determine the allocation of foreign aid. While evidence for this quid-pro-quo view has been found in various contexts, interestingly, so far the literature has not inquired into the question as to whether ODA is used as a strategic instrument in the bargaining of bilateral treaties.

With regard to bilateral tax treaties, due to their benefits being predominantly on the side of capital-exporting countries, a number of legal and economic scholars have pleaded for the inclusion of revenue sharing mechanisms into DTAs between countries with asymmetric investment positions (e.g., Paolini, Pistone, Pulina, & Zagler, 2015; Thuronyi, 2010). To our knowledge, potential connections between DTAs and existing foreign aid payments have, however, only been addressed by Braun and Zagler (2014). In a pure cross-sectional study for 2010, the authors find a positive association between bilateral ODA commitments and the existence of DTAs.

The present paper contributes to the literature on the determinants of foreign aid by providing evidence that foreign aid is used strategically to put pressure on or reward recipient countries when it comes to negotiating bilateral treaties from which the donor country typically benefits more than the recipient country. We examine DTAs that are signed between donor and recipient countries between 1991 and 2012. Using a fixed effects Poisson model, we find that, on average, donor countries’ aid commitments to the other signature state increase by about 22% in the year of signature. Evaluated at the sample mean, this translates into around US$6 million additional aid commitments in a DTA signatory year. We interpret this increase in ODA as compensation for DTA signature.

This finding is important because it shows a new dimension and a further channel in which foreign aid may be used as a strategic policy instrument. From this perspective, this paper additionally contributes to the discussion regarding the efficiency of aid, since it is heavily dependent on its allocation (Faye & Niehaus, 2012).

The paper proceeds as follows. The next section briefly discusses the institutional background of asymmetric DTAs. In Section 3, we set up a simple Nash bargaining model analysing the supply of tax-related information as provided for in bilateral tax treaties. After describing the data and methodology in Sections 4 and 5, we empirically test the model hypothesis that bilateral foreign aid is used as a strategic instrument to reward countries for their agreeing to sign a DTA (Section 6). Section 7 presents a series of robustness checks and Section 8 concludes.

2 INSTITUTIONAL BACKGROUND: ASYMMETRIC DTA

Foremost, DTAs serve to allocate taxing powers between signatory states in order to prevent double taxation in cross-border situations. In addition, DTAs are increasingly seen as instruments to prevent double non-taxation of international economic activities. For instance, DTAs include anti-abuse provisions and enable or facilitate the exchange of information and administrative assistance between the tax authorities of the two signatory states. Overall, DTAs are signed to increase tax certainty for companies engaged in international business (for instance, multinational enterprises) and to ensure efficient tax collection for signatory states.

Most DTAs are based on the model tax conventions (MTCs) proposed by the OECD and the UN and thus are very similar. The fact that the same underlying principles are embodied in all treaties makes them especially suitable for our analysis. This ensures that we have a large number of similar treaties from which we can generally expect similar effects and thus can treat them equally in the empirical analysis.2

The following paragraphs introduce the rules regarding the allocation of taxing rights between the two signatory states, by focusing on the taxation of businesses, while disregarding the rules that affect only individuals. Generally, DTAs distinguish two types of income, for which different allocation rules apply: active business income and passive income. Active business income simply means business profits. The primary right to tax is with the residence country. Only when a (multinational) company has a substantial business presence (e.g., a fixed place of business)—a so-called permanent establishment (PE)—in the other state, then the other state has the right to tax the profits attributable to the PE (Article 7 OECD MTC). The residence country is then obliged to prevent double taxation by applying the exemption or credit method as provided for in Article 23 of the OECD MTC.

Thus, the definition of a PE and the method of defining the income to be allocated to a PE decide on which state is allowed to tax the respective income. The OECD MTC (and the UN MTC, albeit to a lesser extent) generally shifts taxing powers from the source to the residence country by defining both a PE and the income attributable to the PE more narrowly than many national legislations—especially in developing countries (see, e.g., Braun & Fuentes, 2016).

When it comes to passive income, that is, dividends, royalties and interest payments, the residence country has the primary right to tax, and the source country is granted the right to levy limited withholding tax rates on these types of income (see Articles 10, 11, and 12 of the OECD MTC). Typically, DTAs provide for a reduction of withholding tax rates in the source state, which implies “a revenue transfer from the net capital importer to the net capital exporter” (Rixen & Schwarz, 2009, p. 446). Analysing a sample of 18 European countries’ DTAs with developing countries, Eurodad (2016) finds that the withholding tax rates on dividends, royalties and interest stipulated in these DTAs are on average 3.8% lower than the respective rates in domestic laws.3

A number of case studies discuss such features inherent in DTAs in great detail and attempts to quantify their impact on developing countries.4 These studies find that asymmetric DTAs, that is DTAs signed between capital exporters and capital importers, which are based on the OECD MTC (and to a lesser degree also the ones based on the UN MTC) imply inherent downsides for capital-importing countries by limiting their taxing powers (also see, e.g., Dagan, 2000; Daurer, 2013; Rixen & Schwarz, 2009).

Due to rapidly growing interdependencies between economies, the exchange of information has gained more and more importance for respective tax authorities. Particularly, multinationals’ cross-border activities raise the awareness, since the majority of national tax systems are residence-based. Furthermore, individual source taxation rates have declined over recent years. The monitoring of taxpayers’ international activities, followed by a correct assessment of tax liabilities, is therefore crucial.

While the tax authorities of capital-exporting economies typically have a greater interest in receiving tax-related information, also net capital-importing countries benefit from the exchange of information in tax matters. Tax authorities from low-income countries are often interested in requesting information regarding the capital of their high net worth individuals parked abroad. Additionally, firms resident in developing countries are increasingly becoming international. Outward foreign direct investment (FDI) flows from developing and transition economies have been increasing, and in 2015 made up 27.7% of global FDI outflows. However, in the same year, the combined outward FDI stocks from developing and transition countries only amounted to 22.4% of worldwide outward FDI stocks.5

In the majority of cases, the (net) information flow mainly flows from the low-income country to the high-income country.6 Given that retrieving and providing such information is costly, the increased demand for information may thus aggravate the structural disadvantages arising from DTAs for capital-importing countries. The next section formally illustrates the implicit disadvantage in DTAs and why compensation is expected in case of a voluntary signature of a DTA between two countries with an asymmetric investment position.

3 THE MODEL

If a resident (corporation) in one country (country R henceforth) pursues economic activities in another country (country S to indicate the source of income) that are liable to taxation in its country of residence, this country requires information on the tax base and the amount of taxes due. There are several ways to obtain this information. First, the tax authority can ask the tax subject herself. For obvious reasons,7 the tax authority may not receive the correct reply. As opposed to economic activity in its own territory, the tax authority in country R cannot investigate abroad due to a lack of jurisdiction. However, it can ask the tax authorities abroad to assist in verifying the information of its tax subject. Country S may be reluctant to supply this type of information, due to direct and indirect costs. Direct costs obviously include information collection and audit costs. Indirect costs are effects that impact country S, as agents will require excess withholding taxes back as a next step, or move their business to a third country, thus withdrawing tax base and foreign direct investment from country S, leading to repercussions on GDP and employment. Country S will therefore supply very little information to other jurisdictions. To circumvent this difficulty, an incentive compatible contract can be signed between the two countries R and S.

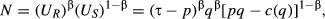

(1)

(1) ,

,  . We define average costs as

. We define average costs as  . There is a rent of information sharing (and hence the possibility of a mutually beneficial deal) if and only if the maximum willingness to pay of country R exceeds the marginal cost of procurement of country S:

. There is a rent of information sharing (and hence the possibility of a mutually beneficial deal) if and only if the maximum willingness to pay of country R exceeds the marginal cost of procurement of country S:

(2)

(2)Suppose for a moment that information could be provided and demanded by many different agents. This would lead to perfect competition in a market for information, and information would be exchanged until Equation 2 is satisfied with equality, and, due to perfectly elastic demand, the price for information would be equal to the gain for country R from the information,  . This is the exact opposite of the current practice in DTAs, where information must be shared free of charge,

. This is the exact opposite of the current practice in DTAs, where information must be shared free of charge,  . Note that in the latter case, country S would willingly share only information that comes at no cost, and this may be the reason for the low number of information exchanges registered empirically.

. Note that in the latter case, country S would willingly share only information that comes at no cost, and this may be the reason for the low number of information exchanges registered empirically.

(3)

(3) (4)

(4) , the Nash maximand reads:

, the Nash maximand reads:

(5)

(5) and

and  must be positive, or

must be positive, or  . Taking the first-order condition with respect to the price p gives:

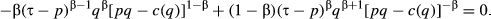

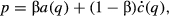

. Taking the first-order condition with respect to the price p gives:

(6)

(6)It turns out that the result is a weighted average between the reservation price of country R,  , and the average cost of providing this information,

, and the average cost of providing this information,  , for country S. The price will equal the reservation price of country R,

, for country S. The price will equal the reservation price of country R,  if its bargaining power is null,

if its bargaining power is null,  . In this case, country S can extract all rents for itself. The price will equal average costs of country S if its bargaining power is null,

. In this case, country S can extract all rents for itself. The price will equal average costs of country S if its bargaining power is null,  . In this case, country R can extract all rents for itself.

. In this case, country R can extract all rents for itself.

The price will be null if and only if average costs are zero and the bargaining power  equals unity. Coincidentally, this is the current legal situation in double tax agreements with provisions for the exchange of information. While this may not pose a problem in situations where both countries possess a similar amount of information,9 when the countries are asymmetric, with one country the predominant provider of information and the other country the predominant receiver, the above model predicts little to no information to be exchanged, if average costs of acquiring information are non-negligible, as argued above. This asymmetric situation is typical for developing countries, which are capital importers and therefore should be able to retrieve information requested by the capital-exporting developed country. We therefore suggest that DTAs should include cost10 and revenue sharing to succeed in retrieving information.

equals unity. Coincidentally, this is the current legal situation in double tax agreements with provisions for the exchange of information. While this may not pose a problem in situations where both countries possess a similar amount of information,9 when the countries are asymmetric, with one country the predominant provider of information and the other country the predominant receiver, the above model predicts little to no information to be exchanged, if average costs of acquiring information are non-negligible, as argued above. This asymmetric situation is typical for developing countries, which are capital importers and therefore should be able to retrieve information requested by the capital-exporting developed country. We therefore suggest that DTAs should include cost10 and revenue sharing to succeed in retrieving information.

(7)

(7) and is equivalent to the amount of information exchanged under perfect competition 2. Nash bargaining therefore does not distort the optimal amount of information exchanged. We can infer the quantity of information exchanged by invoking the inverse of Equation 2:

and is equivalent to the amount of information exchanged under perfect competition 2. Nash bargaining therefore does not distort the optimal amount of information exchanged. We can infer the quantity of information exchanged by invoking the inverse of Equation 2:

(8)

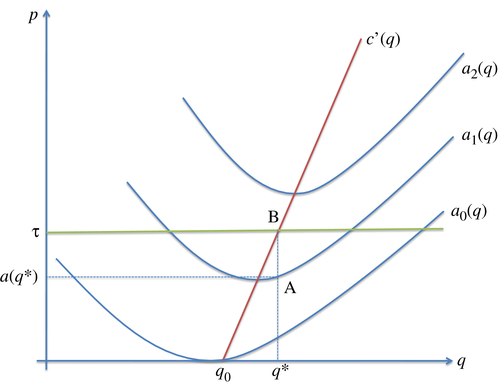

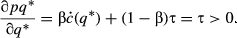

(8)Figure 1 illustrates the argument. We have depicted the reservation price of country R as a horizontal green line. We have also drawn the marginal cost curve of country S as an upward sloping red line. At the intersection of these two curves, point B, we identify the quantity of information exchanged in the bargaining model. Finally, we have drawn three different average cost curves of country R, which differ only in the amount of fixed costs.  has a minimum above the reservation price, and hence, there exists no solution where information is exchanged.

has a minimum above the reservation price, and hence, there exists no solution where information is exchanged.

The average cost curve  has its minimum below the reservation price and therefore permits the exchange of information.11 The minimum amount at which country S is willing to sell information is indicated by point A. The difference between A and B indicates the total economic rent that can be gained from bargaining. The division of this rent depends on relative bargaining power. If country S has all the bargaining power,

has its minimum below the reservation price and therefore permits the exchange of information.11 The minimum amount at which country S is willing to sell information is indicated by point A. The difference between A and B indicates the total economic rent that can be gained from bargaining. The division of this rent depends on relative bargaining power. If country S has all the bargaining power,  , according to Equation 6, the exchange would happen in point B. If country R has all the bargaining power,

, according to Equation 6, the exchange would happen in point B. If country R has all the bargaining power,  , the price would be set at point A. In both cases, the price exceeds zero.

, the price would be set at point A. In both cases, the price exceeds zero.

The only possibility to have exchange of information at zero cost is depicted by average cost  , where fixed costs and marginal costs below a certain threshold

, where fixed costs and marginal costs below a certain threshold  are null.12 Here, if country R has all the bargaining power, the bargaining outcome would be a corner solution, and a quantity

are null.12 Here, if country R has all the bargaining power, the bargaining outcome would be a corner solution, and a quantity  of information would be exchanged at a prize

of information would be exchanged at a prize  . In this case, information exchange is inefficient, as country R would be willing to pay for additional information and country S would be willing to provide additional information at that price.

. In this case, information exchange is inefficient, as country R would be willing to pay for additional information and country S would be willing to provide additional information at that price.

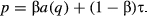

(9)

(9)In the following section, we aim to find evidence in support of this theory of compensation. While there is no DTA that explicitly includes compensation, we test whether there is implicit compensation in place. Compensation may come in many forms. One possibility can be foreign aid paid by the information receiving country to the information provider. We will therefore look at official development assistance (ODA) as an—albeit imperfect—measure of compensation for signing a treaty.

(10)

(10) (11)

(11)Bargaining power can be approximated by the size of a country (population or GDP).13

(12)

(12) is the second derivative of the cost function and ambiguous of sign, so that we cannot draw any conclusions on the impact of the residence country's reservation price on the amount of compensation.

is the second derivative of the cost function and ambiguous of sign, so that we cannot draw any conclusions on the impact of the residence country's reservation price on the amount of compensation.4 DATA

We compile a dyadic panel data set that consists of country-pairs with an ODA donor country on the one hand and an ODA recipient country on the other hand. The analysis covers the period 1991 to 2012. The list of donors includes the 23 states that were DAC (Development Assistance Committee) members as of 2012 (see Table A2 in the Appendix). Apart from Greece, that joined the DAC in 1999, and the Republic of Korea, that joined in 2010, all other countries were members during the entire sample period.14 The recipient countries comprise of the countries included in the 2012 DAC list of potential ODA recipients, which encompasses low and middle-income countries according to the 2012 World Bank income classification. We use bilateral foreign aid commitments as our dependent variable. Information on ODA commitments has been sourced from the OECD DAC database.

As we are interested in the question as to whether ODA is used by donor countries to compensate potential recipient countries when signing a DTA, our main variable of interest concerns DTAs. Information on DTA signatures is taken from the IBFD Tax Research Platform. Between 1991 and 2012, 372 DTAs were signed between 23 donor and 75 recipient countries. Twenty-four of these DTAs are not included in the empirical analysis because there are no aid commitments within these country-pairs in the years analysed.15 The final sample used in the regression analysis, which is further reduced due to missing data in the covariates, includes 293 DTA signatures between 19 donor countries and 68 recipient countries.

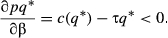

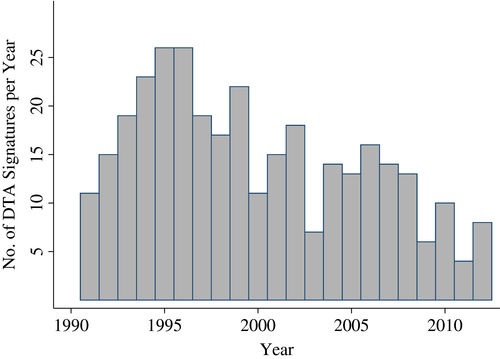

Figure 2 shows the distribution of these DTA signatures over the sample period. The number of yearly DTA signatures ranges between four in 2011 and 27 in 1995 and 1996. On average, 14.8 DTAs were signed each year, with a higher average number of yearly signatures in the 1990s than in the following years.

Source: IBFD Taxation Platform, own illustration.

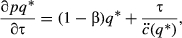

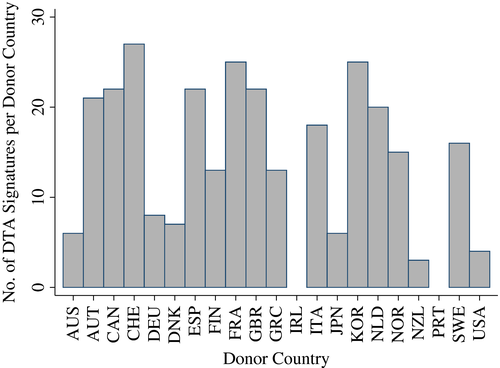

[Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]The analysis includes the DAC donor countries as of 2012 with the exception of Ireland, Portugal, Belgium and Luxembourg (see Figure 3). Ireland and Portugal signed DTAs but did not commit to any aid to the other signatory states during the sample period. Belgium and Luxembourg are not listed separately in the UNCOMTRADE database for bilateral trade and are hence also omitted from the empirical analysis. During the 22 years covered by the analysis, each donor country signed on average 15.6 DTAs. The number of new DTAs per donor country varies between three (New Zealand) and 27 new treaties (Switzerland).

Source: IBFD Taxation Platform, own illustration.

[Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]The majority of the recipient countries are middle-income countries. In total, 152 DTAs with upper middle-income countries, and 117 with lower middle-income countries, and only 24 DTAs with low-income countries are covered by the analysis. Table A3 in the Appendix presents a complete list of recipient countries with their respective number of treaties concluded between 1991 and 2012 that are included in the analysis.

Geographically, the main area covered is Europe and Central Asia (94 of the analysed DTAs), followed by Asia Pacific (67 DTAs) and sub-Saharan Africa (52 DTAs). In addition, the analysis includes 47 DTAs with Latin America and the Caribbean and 33 DTAs with countries in the Middle East and North Africa.

The explanatory variable of interest is a binary variable, taking the value of one if a country-pair signs a DTA in a particular year and is otherwise zero. We will include leads and lags of this variable to ensure that the relationship is not coincidental. We will also compare the results with a level dummy of DTAs that jumps from zero to unity onwards from the year the DTA is signed. We further include other international treaties, such as preferential trade agreements and bilateral investment treaties. Finally, we include the factors which are generally found to matter for donors when allocating foreign aid: population, poverty, proximity and policies (Clist, 2011).

5 METHODOLOGY

We question as to whether ODA is used by donor countries to compensate potential recipient countries when signing a DTA. To analyse this hypothesis, we use bilateral foreign aid commitments as our dependent variable. Information on ODA commitments comes from the OECD DAC database. The typical distribution of bilateral aid with the large number of zero observations poses a challenge for regression analysis. Log-linearised gravity-type OLS models with fixed effects are not the most suitable models for this kind of data. Not only do these models require an arbitrary adjustment of the dependent variable, but, in the presence of heteroscedasticity, the estimates are inconsistent, and their interpretation can be misleading, even when robust standard errors are applied (Silva & Tenreyro, 2006).

Instead, Silva and Tenreyro (2006) suggest the use of fixed effects Poisson models (FEPM). These models explicitly take the non-linearity of the dependent variable into account, are robust to heteroscedasticity, and control for unobserved heterogeneity. Moreover, in FEPM, the dependent variable does not need to follow a Poisson distribution, nor does it need to be an integer number. For the estimator to be consistent, only the correct specification of the conditional mean is required. In addition, and very importantly in our case, the FEPM also performs well under a large number of zero observations in the dependent variable. Besides, the parameter estimates can be directly interpreted as elasticities (Silva & Tenreyro, 2006, 2011).

(13)

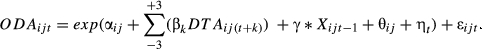

(13)Total bilateral ODA commitments (in constant US$) are the dependent variable. The explanatory variable of interest is  , a binary variable taking the value of one if a country-pair

, a binary variable taking the value of one if a country-pair  signs a DTA in year

signs a DTA in year  . Additional control variables

. Additional control variables  are lagged by one period. Country-pair fixed effects

are lagged by one period. Country-pair fixed effects  , year-fixed effects

, year-fixed effects  and a constant

and a constant  are included, and

are included, and  stands for the error term.

stands for the error term.

6 EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE

This section presents the results based on the regression model described above. Our main question is whether foreign aid might be used to make the signature of a DTA sweeter. The sample is thus restricted to country-pairs that have signed a DTA during the sample period from 1991 to 2012. Our empirical analysis also accounts for important factors, which the literature on the determinants of aid has found to matter for donors when allocating foreign aid: population, poverty, proximity, and policies (Clist, 2011).17 We start by describing these control variables in more detail and will then turn to the main effects.

First, as a measure of country size, we include the (logged) populations of the donor and recipient countries ( and

and  ). As expected, the coefficients for both variables are positive, implying that, on average and ceteris paribus, larger countries give more aid, and larger countries also receive more aid. However, they are insignificant at conventional levels in most estimations.

). As expected, the coefficients for both variables are positive, implying that, on average and ceteris paribus, larger countries give more aid, and larger countries also receive more aid. However, they are insignificant at conventional levels in most estimations.

Second, to proxy poverty and the needs of the recipient countries, their respective (logged) levels of GDP per capita (in constant USD) are included in the analysis  . The estimation results suggest that poverty is not a statistically significant determinant of foreign aid—at least for our sample of country-pairs and the time period analysed. The GDP per capita of the donor country

. The estimation results suggest that poverty is not a statistically significant determinant of foreign aid—at least for our sample of country-pairs and the time period analysed. The GDP per capita of the donor country  , on the other hand, turns out to be a strong predictor for the amount of bilateral aid that a country gives.

, on the other hand, turns out to be a strong predictor for the amount of bilateral aid that a country gives.

Third, traditional measures of proximity such as distance between the two signatory states, a common colonial history or a common official language, are captured by the country-pair fixed effects in our estimations. Additionally, we specifically account for economic ties between the two signatory states by adding the relative volume of bilateral trade to measure the “economic distance” between two countries:  . Bilateral trade is measured as the sum of imports of country i from country j plus the imports of country j from country i in year t (in constant USD). The absolute volume is then scaled by the sum of the GDPs of both countries (also measured in constant USD). This variable turns out to be negative, but statistically insignificant in most regressions.

. Bilateral trade is measured as the sum of imports of country i from country j plus the imports of country j from country i in year t (in constant USD). The absolute volume is then scaled by the sum of the GDPs of both countries (also measured in constant USD). This variable turns out to be negative, but statistically insignificant in most regressions.

Forth, when deciding to which countries to allocate how much aid, also recipient countries’ policies have been found to matter for donors. To account for the recipient countries’ policies, we include the variable  , which represents the combined score of the civil liberty and political rights indicators as provided by Freedom House. Inverted scores have been used to make the interpretation more intuitive, that is, higher scores stand for more democratic regimes. In our regressions, the variable is positive and statistically insignificant.

, which represents the combined score of the civil liberty and political rights indicators as provided by Freedom House. Inverted scores have been used to make the interpretation more intuitive, that is, higher scores stand for more democratic regimes. In our regressions, the variable is positive and statistically insignificant.

Finally, column (1) of Table 1 includes three distinct international treaty dummies accounting for bilateral investment treaties, preferential trade agreements and double tax agreements ( ), to ensure that the effect of the DTA is not confounded with the effects of other treaties. They each switch from zero to one starting in the year in which a respective treaty is signed. Preferential trade agreements turn out to be statistically insignificant. As preferential trade agreements are typically multilateral agreements, bilateral compensation as proxied by an increase in bilateral aid is unlikely to be expected. With respect to DTAs, given that these treaties are typically very persistent (there are only few instances of treaties being terminated), a long-term effect on the level of ODA after their signature (as measured by these dummy variables) does not seem very likely. Rather, a temporary effect around the signatory date seems more plausible if this increase is to be interpreted as a compensation.18

), to ensure that the effect of the DTA is not confounded with the effects of other treaties. They each switch from zero to one starting in the year in which a respective treaty is signed. Preferential trade agreements turn out to be statistically insignificant. As preferential trade agreements are typically multilateral agreements, bilateral compensation as proxied by an increase in bilateral aid is unlikely to be expected. With respect to DTAs, given that these treaties are typically very persistent (there are only few instances of treaties being terminated), a long-term effect on the level of ODA after their signature (as measured by these dummy variables) does not seem very likely. Rather, a temporary effect around the signatory date seems more plausible if this increase is to be interpreted as a compensation.18

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POP_donor(ln) | 2.729 | 2.719 | 2.733 | 3.062 | 2.827 | 3.361 | 2.536 |

| (2.174) | (2.167) | (2.178) | (2.216) | (2.157) | (2.173) | (2.322) | |

| POP_recipient(ln) | −0.035 | −0.052 | −0.051 | −0.116 | −0.058 | −0.506 | −0.050 |

| (0.809) | (0.795) | (0.793) | (0.820) | (0.785) | (1.280) | (0.797) | |

| GDPPC_donor(ln) | 2.289*** | 2.299*** | 2.316*** | 2.338*** | 2.323*** | 2.840** | 2.286** |

| (0.878) | (0.871) | (0.875) | (0.882) | (0.890) | (1.122) | (0.898) | |

| GDPPC_recipient(ln) | 0.155 | 0.157 | 0.158 | 0.172 | 0.140 | −0.346 | 0.158 |

| (0.304) | (0.305) | (0.302) | (0.302) | (0.299) | (0.835) | (0.304) | |

| Trade/GDP (ln) | −0.008 | −0.008 | −0.009 | −0.009 | −0.009 | −0.009 | −0.008 |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | |

| Democracy_freedom | 0.015 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.013 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.016 |

| (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.025) | (0.026) | |

| Investment treaty | 0.361*** | 0.354*** | 0.355*** | 0.381*** | 0.360*** | 0.352*** | 0.351*** |

| (0.113) | (0.110) | (0.110) | (0.112) | (0.111) | (0.109) | (0.115) | |

| Trade agreement | 0.021 | 0.021 | 0.023 | 0.005 | 0.022 | 0.032 | 0.019 |

| (0.191) | (0.192) | (0.193) | (0.194) | (0.182) | (0.192) | (0.188) | |

| DTA | 0.016 | ||||||

| (0.111) | |||||||

| DTA(−3) | 0.015 | 0.007 | |||||

| (0.142) | (0.147) | ||||||

| DTA(−2) | −0.151 | −0.146 | |||||

| (0.154) | (0.155) | ||||||

| DTA(−1) | −0.033 | −0.030 | |||||

| (0.120) | (0.126) | ||||||

| DTA(0) | 0.216** | 0.219** | 0.207** | 0.344** | 0.351** | 0.382 | |

| (0.093) | (0.098) | (0.101) | (0.144) | (0.155) | (0.409) | ||

| DTA(+1) | 0.064 | 0.068 | |||||

| (0.126) | (0.129) | ||||||

| DTA(+2) | 0.022 | 0.015 | |||||

| (0.071) | (0.073) | ||||||

| DTA(+3) | 0.140 | 0.134 | |||||

| (0.092) | (0.094) | ||||||

| Bilateral FDI(ln) | 0.000 | ||||||

| (0.006) | |||||||

| DTA(0)*FDI(ln) | 0.021* | ||||||

| (0.012) | |||||||

| GDP_ratio | −0.567 | ||||||

| (0.936) | |||||||

| DTA(0)*GDP_ratio | −0.037 | ||||||

| (0.036) | |||||||

| Corporate tax | 0.363 | ||||||

| (1.187) | |||||||

| DTA(0)*corporate tax | −0.432 | ||||||

| (1.151) | |||||||

| Observations | 6,273 | 6,273 | 6,273 | 5,887 | 6,208 | 6,269 | 6,273 |

| Number of groups | 293 | 293 | 293 | 275 | 293 | 293 | 293 |

| Wald χ2 | 196.98 | 199.66 | 238.57 | 254.66 | 197.17 | 201.12 | 203.11 |

| p-value | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 |

| Log-pseudolikelihood | −70,359.65 | −70,177.19 | −70,021.51 | −66,996.30 | −69,725.15 | −70,105.91 | −70,163.67 |

Notes:

- Estimated with Poisson maximum-likelihood fixed effects. The dependent variable is total bilateral ODA commitments; all explanatory variables are lagged by one period; all regressions include country-pair FE, year FE and a constant; robust standard errors in parentheses; time period 1991–2012.

- ***p < .01, **p < .05, *p < .1.

In column (1)—just like in all other specifications—bilateral investment treaties (BITs) turn out positive and significant. BITs have always played an important role in development economics. Swenson (2009) notes the BITs have always followed FDI, but only since the mid-1990s have they drawn additional FDI flows. We find that about half the observations in our sample exhibit a BIT in place, just about as many as DTAs. Indeed, there is a correlation of 0.4, which justifies the inclusion of BITs as a control variable. BITs are different to DTAs. The literature tends to agree that BITs are foreign aid with other means (Vandefelde, 2010). Neumayer (2006) finds that BITs follow the same explanatory pattern as foreign aid, and it comes as little surprise that these investment treaties turn out significant in our regressions. As opposed to DTAs, however, we could not find any evidence for foreign aid to increase significantly around the time a BIT is signed.

As we are ultimately interested in the connection between DTA signatures and foreign aid, column (2) includes DTA(0), which is a dummy variable that is 1 only in the year where a DTA is signed and zero otherwise. This variable is positive and statistically significant, meaning that in the year a developing country signs a DTA with a DAC donor country, the developing country receives 21.6% more aid from that specific donor country. This additional foreign aid may be given with a view to make the deal sweeter for the capital-importing country.

(14)

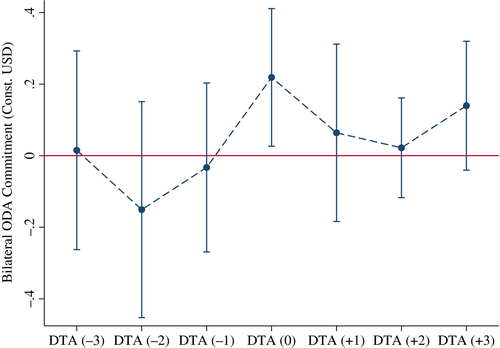

(14)Column (3) of Table 1 shows the results, and Figure 4 depicts the coefficients of the DTA variable and its three leads and lags. Bilateral aid commitments tend to be lower during the 3 years prior to the signature of a DTA (this effect is however not statistically significant at conventional levels). Donor countries seem to hold back (or reduce) bilateral aid commitments, possibly to put pressure on the recipient country to sign the treaty.

In the signatory year, the recipient country is compensated by an increase in bilateral ODA commitments by 22%. This effect is similar in size and consistently significant in all specifications. Evaluated at the sample mean, this corresponds to around US$6.6 million of bilateral aid commitments that can, on average, be attributed to a DTA signature. To put this number into relation with the size of the recipient country, this translates into about US$387,000 per one million inhabitants. Over all 293 DTAs signed during the sample period, this adds up to roughly US$ two billion.

As capital-exporting countries disproportionately benefit from DTAs, our conclusions rely on the argument that donor countries typically are capital-exporting countries and recipient countries are capital-importing countries. Looking at bilateral average investment stocks over the sample period from the perspective of the donor country, the outward FDI stocks exceeded the inward stocks for 210 country-pairs, corresponding to 71.7% of our sample. For 22.2% of the sample, or 65 country-pairs, the average net investment positions were zero, and in only 18 cases the average inward stocks were higher than the outward stocks 6.1%.20 In column (4) of Table 1, we thus delete from the sample the 18 country-pairs for which the donor country's outward FDI stocks are inferior to its inward stocks (on average over the sample period). The result remains unchanged. These 18 country-pairs thus seem not to affect the results.

Our model in Section 3 has generated three testable hypotheses on an increase in foreign aid around the signature of a DTA, Equations 10-11–12. We can therefore empirically test the model predictions regarding the role of: (i) the strength of economic ties; (ii) the relative bargaining power of the two countries; and (iii) the residence country's reservation price, that is, its corporate tax rate.

The first hypothesis derived from the model is that stronger economic ties increase compensation. Economic ties between the two countries are proxied by bilateral FDI stocks  (see column (5) in Table 1). The positive and significant interaction effect suggests that the stronger the economic ties are between two countries, the more compensation the donor country is willing to pay for the signature of a DTA. This implies that in addition to the level effect or lump sum compensation, which is captured by the DTA dummy variable, additional compensation is paid relative to the strength of economic ties.

(see column (5) in Table 1). The positive and significant interaction effect suggests that the stronger the economic ties are between two countries, the more compensation the donor country is willing to pay for the signature of a DTA. This implies that in addition to the level effect or lump sum compensation, which is captured by the DTA dummy variable, additional compensation is paid relative to the strength of economic ties.

The second hypothesis derived from the model is that the higher the relative bargaining power of the residence country, the lower the compensation for a DTA. The relative bargaining power is proxied by the ratio of the two countries’ GDPs. The interaction effect between this GDP ratio with the DTA variable indicates the impact of the relative bargaining power on ODA payments for a DTA (see column (6) in Table 1). The coefficient has the expected negative sign, is however not statistically significant.

Finally, in column (7), we analyse the effect of the residence country's corporate income tax rate (Corporate Tax) on the compensation payout. The model predicts no clear impact, and also the empirical regression does not yield a clear result with the interaction effect between the Corporate Tax and DTA variable being statistically insignificant.21

To sum up, the data support Hypothesis 1. There is statistical evidence suggesting that ceteris paribus recipient countries with closer economic ties with the donor country tend to receive more foreign aid in exchange for a DTA. The data also do not outrightly contradict the second hypothesis, suggesting that the higher the relative bargaining power of a residence country, the lower is the price it is prepared to pay for a DTA. Hypothesis 3, that is, an unclear effect of the residence country's reservation price, is reflected by the insignificant empirical results. Most importantly, all estimations are in line with our main prediction, that is, that there is a price paid for the signature of a DTA.

7 ROBUSTNESS

Table A6 shows additional regressions that include additional and alternative control variables to test whether the results depend on the covariates included. First, to account for the fact that donors increase their aid to states that are affected by natural disasters, columns (1)–(3) include the (logged) total number of persons affected by natural disasters (from the EM-DAT database). The variable Natural Catastrophe hence proxies the occurrence and strength of devastation of natural disasters. As humanitarian aid tends to be promised (and given) promptly without much time delay, the variable is not lagged by one period. Its coefficient is close to zero and not significant in our regressions, which may be due to the fact that humanitarian aid represents only a minor fraction of total aid (Qian, 2015).

Second, we control for additional political factors that have been found to affect foreign aid. Empirical evidence suggests that bilateral aid is associated with the membership in the UN Security Council (UNSC) and the alignment in votes in the UN General Assembly (Alesina & Dollar, 2000; Dreher, Nunnenkamp, & Thiele, 2008; Kuziemko & Werker, 2006). To account for UNSC Membership we construct the variable UNSC Membership as a binary variable that takes the value of 1 if two countries of a country-pair are simultaneously members of the UNSC (Table A4 in the Appendix lists the cases). The variable is not statistically significant (see columns (2) and (3) of Table A6). Also agreement in the UN General Assembly (UNGA Agreement) between the two countries of a country-pair turns out not to be associated with bilateral aid commitments in our regressions (see column (3)).

Columns (4)–(7) of Table A6 then include alternative variables to account for the four Ps: poverty, population, policies, and proximity. First, we use the (logged) life expectancy to account for the recipient country's poverty level (see column (4) in Table A6). Akin to the recipient country's GDP per capita in most regressions, also this variable yields no statistically significant impact on ODA payments in our sample.

Second, we include the size of the donor and recipient countries as measured in terms of the (logged) GDP in constant US$. Both  and

and  enter the regression with a positive sign, but just as population also insignificant, leaving the main results qualitatively unchanged (see column (5) in Table A6).

enter the regression with a positive sign, but just as population also insignificant, leaving the main results qualitatively unchanged (see column (5) in Table A6).

Third, the institutional quality in the recipient country is accounted for with a different index. In column (6) in Table A6, we take the index of democracy provided by the Center for Systemic Peace, which classifies countries from “strongly autocratic” to “strongly democratic” ( ). As the democracy index used in the other regressions, this variable is not statistically significant at conventional levels.

). As the democracy index used in the other regressions, this variable is not statistically significant at conventional levels.

Forth, Column (7) uses bilateral FDI stocks relative to the sum of the two countries’ GDPs  instead of the bilateral relative trade volume as a measure of economic proximity. Similar to the bilateral relative trade volume, also the relative bilateral FDI stocks do not show a significant effect on ODA commitments.

instead of the bilateral relative trade volume as a measure of economic proximity. Similar to the bilateral relative trade volume, also the relative bilateral FDI stocks do not show a significant effect on ODA commitments.

Most importantly, the main variable of interest, DTA(0), remains positive and statistically significant at conventional levels in all regressions. The size of the effect varies around 22%.

Finally, Table A7 in the Appendix presents regression results that exclude Greece and Korea, which both joined the DAC committee during our sample period. Also these results suggest increased bilateral foreign aid commitments in the year a DTA is signed. Interestingly, though, when these two countries are excluded, GDP per capita of the donor country does not seem to be a strong predictor of bilateral foreign aid. Rather, the size of the donor country (as measured by its population) becomes statistically significant in most regressions, indicating that—ceteris paribus and on average—larger countries give more aid.

8 CONCLUSIONS

This paper has analysed, both theoretically and empirically, the connection between bilateral foreign aid and double tax agreements. We theoretically claim that in asymmetric situations, where one country is predominantly a capital exporter and the other country a capital importer, a DTA is mutually beneficial if and only if there is compensation for the capital importer, that loses tax base, by the capital exporter. We claim that such a compensation can be given in the form of official development assistance. This need not be the sole form of compensation.

We have tested this hypothesis in a dyadic panel with fixed effects Poisson regression analysis. We have found that recipient countries that sign a DTA with donor countries indeed receive about 22% more foreign aid in the signature year. We can also empirically confirm further predictions of the model.

This paper however can only analyse the patterns emerging from macro data and interpret them in a meaningful and convincing way, and thereby reach rather indirect conclusions about the connections between foreign aid and DTA conclusion. It would be insightful to have access to information that enables researchers to analyse how treaties are actually negotiated. At the moment, little is known about the actual negotiation process as DTAs are still mainly negotiated behind closed doors (e.g., Lang, 2012). Likewise, there is limited information about aid allocation and bargaining processes between donor and recipient countries (e.g., Molenaers, Dellepiane, & Faust, 2015).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Philipp Danninger, Paolo Ghinetti, Eckhard Janeba, Sunghoon Hong, Pasquale Pistone, Marcel Thum, Viktoria Wöhrer, the participants of the Destat Workshop in Cape Town, the WU Department of Economics Research Seminar, the Matax Workshop, the 6d6 Seminar in Novara and the IIPF conference for helpful comments and suggestions to earlier versions of the paper. The authors are also indebted to an anonymous referee for very helpful comments. Financial support from the Norwegian Science Fund (DeSTaT project) and the OeNB Jubiläumsfonds No. 16017 is gratefully acknowledged. M. Zagler gratefully acknowledges research funding from the Università del Piemonte Orientale. J. Braun gratefully acknowledges financial support from the MannheimTaxation (MaTax) Science Campus, funded by the Leibniz Association, the State of Baden-Württemberg, and the participating institutions ZEW and University of Mannheim.

Notes

intersects the reservation price

intersects the reservation price  . Instead, information is exchanged at a lower level, as additional cost for providing information exceeds the willingness to pay. Information exchange in a bargaining model is therefore efficient.

. Instead, information is exchanged at a lower level, as additional cost for providing information exceeds the willingness to pay. Information exchange in a bargaining model is therefore efficient.

APPENDIX A

| Bilateral FDI (ln) | Bilateral FDI stock between the two countries of a country-pair in constant 2015 US$ (converted from current US$ to constant US$ with US GDP deflator (taken from WDI database)) | OECD Foreign Direct Investment Statistics |

| Bilateral Trade(ln) | Bilateral trade volume between two countries in constant 2015 US$ (converted from current US$ to constant US$ with US GDP deflator (taken from WDI database)) | United Nations International Trade Statistics (U.N. COMTRADE) |

| Corporate tax | Tax Rate on corporate profits | IBFD Tax Research Platform |

| Democracy_freedom | Inverted sum of the civil liberty index and the political rights index in the recipient country, ranging from 0 to 15, with higher values referring to higher levels of democracy | Freedom House https://www.freedomhouse.org/report-types/freedom-world |

| Democracy_polity | Measure of democracy in the recipient country, ranging from −10 (strongly autocratic) to +10 (strongly democratic) | Polity IV data set version 2015 ¡p4v2015 and p4v2015d |

| DTA | Binary variable taking the value 1 in all years a double tax agreement is in place | IBFD Tax Research Platform |

| DTA(0) | Binary variable taking the value 1 in the year of the signature of a double tax agreement | IBFD Tax Research Platform |

| GDP_donor(ln) | Logged GDP of the donor country in const 2005 US$ | World Bank World Development Indicators |

| GDP_recipient(ln) | Logged GDP of the recipient country in const 2005 US$ | World Bank World Development Indicators |

| GDPPC_donor(ln) | Logged GDP per capita of the donor country in const 2005 US$ | World Bank World Development Indicators |

| GDPPC_recipient(ln) | Logged GDP per capita of the recipient country in const 2005 US$ | World Bank World Development Indicators |

| Investment treaty | Binary variable taking the value 1 in the year of the signature of a Bilateral Investment Treaty | UNCTAD United Nations http://investmentpolicyhub.unctad.org/IIA |

| Life expectancy_recipient(ln) | Life expectancy at birth, total years (logged), in the recipient country | World Bank, World Development Indicators |

| Natural catastrophe | (logged) total number of persons affected by a natural catastrophe (sum of injured, homeless, and affected persons) | EM-DAT database http://www.emdat.be/ |

| ODA commitments | Total bilateral official development assistance commitments in constant 2014 US$ | OECD International Development Statistics, DAC database |

| POP_donor(ln) | Logged population of the donor country | World Bank World Development Indicators |

| POP_recipient(ln) | Logged population of the recipient country | World Bank World Development Indicators |

| Trade agreement | Binary variable taking the value 1 in the year of the signature of a Preferential Trade Agreement | World Trade Organization https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/region_e/rta_participation_map_e.htm |

| UNGA Agreement | Index measuring agreement in UN General Assembly votes | Streshnev and Voeten (2013) |

| UNSC Membership | Binary variable taking the value 1 if both countries of a country-pair are concurrently members of the UN Security Council | Dreher, Sturm, and Vreeland (2009a) |

| Australia | Greece | Norway |

| Austria | Ireland | Portugal |

| Belgium | Italy | Spain |

| Canada | Japan | Sweden |

| Denmark | Rep. of Korea | Switzerland |

| Finland | Luxembourg | United Kingdom |

| France | The Netherlands | United States |

| Germany | New Zealand |

Notes:

- Even though a DAC member since 1961, the European Union is disregarded as a donor in our analysis. Czech Republic, Iceland, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia joined the DAC in 2013.

| Albania (11) | Ghana (5) | Namibia (3) |

| Algeria (8) | Guinea (1) | Nepal (3) |

| Argentina (10) | Guyana (1) | Nigeria (2) |

| Armenia (8) | India (8) | Pakistan (4) |

| Azerbaijan (9) | Indonesia (2) | Panama (4) |

| Bangladesh (5) | Iran (4) | Papua New Guinea (3) |

| Belarus (6) | Jordan (5) | Peru (2) |

| Belize (1) | Kazakhstan (7) | Philippines (2) |

| Bolivia (5) | Kenya (1) | Senegal (3) |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina (2) | Kiribati (1) | Serbia (6) |

| Botswana (3) | Kyrgyz Republic (5) | South Africa (17) |

| Brazil (1) | Lao PDR (1) | Syrian Arab Republic (2) |

| China (4) | Lebanon (1) | Tajikistan (1) |

| Colombia (4) | Lesotho (1) | Tanzania (1) |

| Cuba (2) | Libya (2) | Thailand (6) |

| Ecuador (4) | Macedonia, FYR (8) | Tunisia (3) |

| Egypt (4) | Malawi (1) | Uganda (3) |

| El Salvador (1) | Malaysia (3) | Ukraine (11) |

| Ethiopia(3) | Mauritius (1) | Uzbekistan (9) |

| Rep Fiji (1) | Moldova (4) | Venezuela (12) |

| Gabon (2) | Mongolia (8) | Vietnam (16) |

| Gambia (2) | Morocco (4) | Zimbabwe (2) |

| Georgia (7) | Mozambique (1) |

Notes:

- Number in brackets shows number of DTAs signed and included in the analysis.

| France–Algeria 2004 & 2005 | France–Vietnam 2008 & 2009 |

| France–Azerbaijan 2012 | France–Zimbabwe 1991 & 1992 |

| France–Botswana 1995 & 1996 | UK–Argentina 1994 & 1995, 1999 & 2000, 2005 & 2006, 2012 |

| France–Gabon 1998 & 1999, 2010 & 2011 | UK–Botswana 1995 & 1996 |

| France–Ghana 2006 & 2007 | UK–Ghana 2006 & 2007 |

| France–Guinea 2002 & 2003 | UK–India 1991 & 1992, 2011 & 2012 |

| France–India 1991 & 1992, 2002 & 2006 | UK–Libya 2008 & 2009 |

| France–Jamaica 2000 & 2001 | UK–South Africa 2007 & 2008, 2011 & 2012 |

| France–Kenya 1997 & 1998 | UK–Uganda 2009 & 2010 |

| France–Libya 2008 & 2009 | UK–Ukraine 2000 & 2001 |

| France–Namibia 1999 & 2000 | UK–Venezuela, RB 1992 & 1993 |

| France–Panama 2007 & 2008 | UK–Vietnam 2008 & 2009 |

| France–South Africa 2007 & 2008, 2011 & 2012 | USA–South Africa 2007 & 2008, 2011 & 2012 |

| France–Syrian Arab Republic 2002 & 2003 | USA–Ukraine 2000 & 2001 |

| France–Venezuela, RB 1992 & 1993 | USA–Venezuela, RB 1992 & 1993 |

Source:

- Dreher et al. (2009a).

| Variable | Mean | SD | Min. | Max. | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilateral FDI(ln) | −6.853 | 8.906 | −13.816 | 10.662 | 6,208 |

| Corporate tax | 0.334 | 0.07 | 0.2 | 0.58 | 6,273 |

| Democracy_freedom | 7.8 | 3.217 | 2 | 14 | 6,273 |

| Democracy_polity | 2.09 | 6.399 | −9 | 10 | 6,180 |

| DTA | 0.605 | 0.489 | 0 | 1 | 6,273 |

| DTA(0) | 0.047 | 0.211 | 0 | 1 | 6,273 |

| GDP_donor(ln) | 27.253 | 0.949 | 24.945 | 30.259 | 6,273 |

| GDP_recipient(ln) | 23.997 | 1.7 | 17.985 | 29.065 | 6,273 |

| GDPPC_donor(ln) | 10.354 | 0.363 | 9.086 | 11.124 | 6,273 |

| GDPPC_recipient(ln) | 7.321 | 0.940 | 4.717 | 9.116 | 6,273 |

| Investment treaty | 0.587 | 0.492 | 0 | 1 | 6,273 |

| LifeExpectancy_recipient(ln) | 4.197 | 0.116 | 3.706 | 4.37 | 6,225 |

| Natural catastrophe | 7.429 | 5.86 | 0 | 19.65 | 6,273 |

| ODA commitments | 29.937 | 104.09 | 0 | 4284.81 | 6,273 |

| POP_donor(ln) | 16.899 | 1.034 | 15.018 | 19.557 | 6,273 |

| POP_recipient(ln) | 16.676 | 1.592 | 11.171 | 21.019 | 6,273 |

| Trade agreement | 0.112 | 0.315 | 0 | 1 | 6,273 |

| Trade/GDP(ln) | −11.009 | 7.005 | −43.569 | −3.083 | 6,273 |

| UNGA Agreement | 0.741 | 0.121 | 0.104 | 1 | 5,669 |

| UNSC Membership | 0.011 | 0.103 | 0 | 1 | 6,273 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POP_donor(ln) | 2.754 | 2.591 | 2.673 | 2.203 | 3.374 | 2.942 | |

| (2.191) | (2.115) | (2.007) | (2.252) | (2.166) | (2.171) | ||

| POP_recipient(ln) | −0.073 | −0.127 | 0.300 | 0.058 | −0.137 | 0.116 | |

| (0.809) | (0.811) | (0.759) | (0.836) | (0.811) | (0.710) | ||

| GDPPC_donor(ln) | 2.315*** | 2.356*** | 2.367*** | 2.426*** | −0.418 | 2.592*** | 2.257** |

| (0.875) | (0.869) | (0.914) | (0.861) | (2.464) | (0.841) | (0.903) | |

| GDPPC_recipient(ln) | 0.160 | 0.162 | 0.403 | 0.209 | 0.229 | 0.183 | |

| (0.302) | (0.300) | (0.313) | (0.805) | (0.301) | (0.299) | ||

| Trade/GDP (ln) | −0.009 | −0.009 | −0.006 | −0.010 | −0.009 | −0.007 | |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.010) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | ||

| Democracy_freedom | 0.015 | 0.016 | −0.002 | 0.015 | 0.016 | 0.015 | |

| (0.026) | (0.027) | (0.031) | (0.028) | (0.026) | (0.026) | ||

| Investment treaty | 0.357*** | 0.365*** | 0.378*** | 0.383*** | 0.355*** | 0.371*** | 0.352*** |

| (0.110) | (0.110) | (0.113) | (0.107) | (0.110) | (0.111) | (0.110) | |

| Trade agreement | 0.023 | 0.023 | 0.063 | −0.005 | 0.023 | 0.081 | 0.019 |

| (0.193) | (0.193) | (0.188) | (0.192) | (0.193) | (0.197) | (0.184) | |

| DTA(−3) | 0.013 | 0.018 | −0.047 | 0.010 | 0.015 | 0.038 | 0.024 |

| (0.144) | (0.144) | (0.153) | (0.144) | (0.142) | (0.153) | (0.137) | |

| DTA(−2) | −0.151 | −0.154 | −0.189 | −0.154 | −0.151 | −0.143 | −0.147 |

| (0.153) | (0.152) | (0.161) | (0.156) | (0.154) | (0.158) | (0.150) | |

| DTA(−1) | −0.033 | −0.034 | −0.063 | −0.036 | −0.033 | −0.013 | −0.031 |

| (0.120) | (0.120) | (0.125) | (0.125) | (0.120) | (0.134) | (0.120) | |

| DTA(0) | 0.218** | 0.224** | 0.184* | 0.214** | 0.219** | 0.238** | 0.220** |

| (0.098) | (0.098) | (0.107) | (0.101) | (0.098) | (0.097) | (0.010) | |

| DTA(+1) | 0.065 | 0.071 | 0.044 | 0.058 | 0.064 | 0.101 | 0.062 |

| (0.126) | (0.125) | (0.128) | (0.130) | (0.126) | (0.123) | (0.127) | |

| DTA(+2) | 0.018 | 0.024 | −0.001 | 0.010 | 0.022 | 0.048 | 0.024 |

| (0.074) | (0.073) | (0.072) | (0.071) | (0.071) | (0.071) | (0.072) | |

| DTA(+3) | 0.139 | 0.141 | 0.116 | 0.126 | 0.140 | 0.167* | 0.142 |

| (0.092) | (0.092) | (0.095) | (0.093) | (0.092) | (0.090) | (0.092) | |

| Natural catastrophe | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | ||||

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | |||||

| UNSC Membership | 0.248 | 0.213 | |||||

| (0.171) | (0.164) | ||||||

| UNGA Agreement | −0.382 | ||||||

| (0.595) | |||||||

| LifeExpectancy_recipient(ln) | −1.006 | ||||||

| (1.376) | |||||||

| GDP_donor(ln) | 2.733 | ||||||

| (2.178) | |||||||

| GDP_recipient(ln) | −0.051 | ||||||

| (0.793) | |||||||

| Democracy_polity | −0.014 | ||||||

| (0.016) | |||||||

| FDI/GDP (ln) | 0.002 | ||||||

| (0.006) | |||||||

| Observations | 6,273 | 6,273 | 5,669 | 6,275 | 6,273 | 6,186 | 6,208 |

| Number of groups | 293 | 293 | 286 | 293 | 293 | 289 | 293 |

| Wald χ2 | 241.04 | 232.08 | 214.25 | 228.62 | 238.58 | 228.51 | 232.58 |

| p-value | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 |

| Log-pseudolikelihood | −70,041.10 | −69,837.37 | −64,602.43 | −69,232.02 | −70,021.49 | −68,686.30 | −69,786.05 |

Notes:

- Estimated with Poisson maximum-likelihood fixed effects. The dependent variable is total bilateral ODA commitments; all explanatory variables are lagged by one period (except for Natural Catastrophe and UNSC Membership); all regressions include country-pair FE, year FE and a constant; robust standard errors in parentheses; time period 1991–2012.

- ***p < .01, **p < .05, *p < .1.

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POP_donor(ln) | 3.615 | 3.452 | 3.667* | 3.067 | 4.108* | 3.726* | |

| (2.206) | (2.130) | (2.039) | (2.222) | (2.176) | (2.196) | ||

| POP_recipient(ln) | 0.092 | 0.038 | 0.426 | 0.190 | 0.043 | 0.265 | |

| (0.815) | (0.818) | (0.772) | (0.842) | (0.810) | (0.716) | ||

| GDPPC_donor(ln) | 1.207 | 1.253 | 1.325 | 1.318 | −2.361 | 1.721* | 1.186 |

| (0.965) | (0.959) | (0.999) | (0.958) | (2.507) | (0.907) | (0.985) | |

| GDPPC_recipient(ln) | 0.180 | 0.183 | 0.420 | 0.048 | 0.267 | 0.201 | |

| (0.297) | (0.294) | (0.305) | (0.808) | (0.296) | (0.291) | ||

| Trade/GDP (ln) | −0.008 | −0.008 | −0.006 | −0.009 | −0.008 | −0.006 | |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.009) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | ||

| Democracy_freedom | 0.020 | 0.021 | 0.002 | 0.021 | 0.022 | 0.020 | |

| (0.026) | (0.026) | (0.030) | (0.028) | (0.026) | (0.026) | ||

| Natural catastrophe | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 | ||||

| (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | |||||

| BIT | 0.351*** | 0.359*** | 0.383*** | 0.378*** | 0.348*** | 0.367*** | 0.345*** |

| (0.112) | (0.113) | (0.114) | (0.109) | (0.113) | (0.115) | (0.113) | |

| PTA | 0.034 | 0.034 | 0.061 | 0.006 | 0.034 | 0.092 | 0.038 |

| (0.198) | (0.198) | (0.195) | (0.199) | (0.197) | (0.203) | (0.193) | |

| DTA(−3) | 0.027 | 0.032 | −0.044 | 0.023 | 0.031 | 0.052 | 0.035 |

| (0.148) | (0.148) | (0.157) | (0.147) | (0.145) | (0.157) | (0.141) | |

| DTA(−2) | −0.153 | −0.158 | −0.194 | −0.157 | −0.153 | −0.144 | −0.151 |

| (0.154) | (0.154) | (0.163) | (0.157) | (0.155) | (0.160) | (0.151) | |

| DTA(−1) | −0.033 | −0.036 | −0.068 | −0.038 | −0.033 | −0.012 | −0.034 |

| (0.121) | (0.121) | (0.127) | (0.126) | (0.121) | (0.134) | (0.121) | |

| DTA(0) | 0.214** | 0.220** | 0.180* | 0.211** | 0.215** | 0.235** | 0.215** |

| (0.100) | (0.099) | (0.108) | (0.103) | (0.100) | (0.099) | (0.102) | |

| DTA(+1) | 0.048 | 0.055 | 0.026 | 0.042 | 0.047 | 0.085 | 0.045 |

| (0.128) | (0.127) | (0.130) | (0.133) | (0.129) | (0.126) | (0.131) | |

| DTA(+2) | 0.005 | 0.011 | −0.008 | 0.006 | 0.012 | 0.038 | 0.012 |

| (0.076) | (0.075) | (0.075) | (0.073) | (0.073) | (0.073) | (0.074) | |

| DTA(+3) | 0.123 | 0.125 | 0.111 | 0.120 | 0.124 | 0.152* | 0.123 |

| (0.094) | (0.093) | (0.097) | (0.095) | (0.093) | (0.091) | (0.093) | |

| UNSC Membership | 0.249 | 0.215 | |||||

| (0.177) | (0.169) | ||||||

| UNGA Agreement | −0.302 | ||||||

| (0.618) | |||||||

| LifeExpectancy_recipient(ln) | −0.887 | ||||||

| (1.399) | |||||||

| GDP_donor(ln) | 3.578 | ||||||

| (2.190) | |||||||

| GDP_recipient(ln) | 0.129 | ||||||

| (0.798) | |||||||

| Democracy_polity | −0.012 | ||||||

| (0.016) | |||||||

| FDI/GDP (ln) | 0.000 | ||||||

| (0.007) | |||||||

| Observations | 5,449 | 5,449 | 4,906 | 5,459 | 5,449 | 5,362 | 5,445 |

| Number of groups | 255 | 255 | 249 | 255 | 255 | 251 | 255 |

| Wald χ2 | 228.57 | 222.02 | 203.63 | 218.21 | 222.33 | 226.17 | 220.28 |

| p-value | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 | .000 |

| Log-pseudolikelihood | −65,246.67 | −65,068.58 | −60,325.19 | −64,665.08 | −65,265.53 | −64,017.29 | −65,137.51 |

Notes:

- Estimated with Poisson maximum-likelihood fixed effects. The dependent variable is total bilateral ODA commitments; all explanatory variables are lagged by one period (except for Natural Catastrophe and UNSC Membership); all regressions include country-pair FE, year FE and a constant; robust standard errors in parentheses; time period 1991–2012.

- ***p < .01, **p < .05, *p < .1.