Inequality, Saving and Global Imbalances: A New Theory with Evidence from OECD and Asian Countries

Abstract

Global imbalances are attributable to savings deficiency in some economies and savings glut in others. The recent global crisis has triggered widespread social conflict over income inequality. The inequality-saving link has again become a pressing issue needing serious attention. We present a new theory to explain why the link between inequality and saving is negative in OECD countries but positive in emerging Asia. We also offer an econometric analysis of differences in inequality-saving links between those economies. We find that aggressive financial services lead to a negative link by creating income illusion for overconsumption, but imperfect financial markets contribute to a positive link by interacting with industrial policies as part of growth strategies while ignoring liquidity constraints on consumption.

1 Introduction

The global crisis triggered by financial meltdown in 2007–08 still has had adverse impacts on the world economy today, resulting in a contraction in output and a rise in unemployment in various countries. Various studies have provided explanations for the causes and effects of this largest financial crisis since the 1929–33 Great Depression. Some studies claim the importance of the relationship between income inequalities, credit booms and financial crises (Rajan, 2010), but others point to low interest rates and usual business cycles as the determinants of the crisis (Bordo and Meissner, 2012). Additional studies place emphasis on the adverse effects of income inequality on aggregate saving (Brown, 2008; Bunting, 2009), financial fragility (Kumhof and Ranciere, 2010) and current account (Kumhof et al., 2012). Our paper offers a new explanation for global imbalances issues by integrating the themes of existing studies that have largely evolved separately.

Our study focuses on cross-country differences in the link between inequality and saving for three reasons. First, many authors view rising inequality as one of the most pressing problems of our age, which can no longer be ignored (Stiglitz, 2009). Second, high public and household debts or low aggregate savings contribute directly to current account deteriorations given capital formation, as implied by the national accounts identity (Bluedorn and Leigh, 2011). Third, the root causes of large global imbalances may coincide with those of the financial crisis (Obstfeld and Rogoff, 2009). It is therefore important to pay attention, as in our paper, to different inequality-saving links across countries that are involved in economic globalisation. We attach importance to the observed fact that income inequality is generally on the rise in many countries while saving rates have become increasingly divergent across those economies. This phenomenon implies a new development in the inequality-saving link worth attention due to its important implication for worsening global imbalances.

A new theory developed in this paper shows that finance can play an important role in determining what kind of inequality-saving link would prevail in a particular economy. This simple theory, different from existing studies (Krueger and Perri, 2006; Iacoviello, 2008), is based on the aggregate analysis of an extended post-Keynesian model. Our result is that income inequality is associated with the saving rate positively if savers’ funds are allocated by the financial sector to investing firms for production as in China and other Asian countries, but negatively if lent to spending households for consumption as in the USA and other OECD countries. Our extension makes a critical difference to the link between inequality and saving. The traditional post-Keynesian model predicts only a positive link as spending is subject to income, but our model can also account for a negative one by harbouring habitual credit use for deficit spending by consumers. We account for different types of the link without resort to complicated rational expectations or intertemporal approaches.

Our theory is consistent with the evidence on the inequality-saving link, which is found to be negative in most OECD countries (Isacan, 2010) but positive in many Asian economies (Li and Zou, 2004). Cross-country differences in this link are attributed to their differing financial systems in our model. Household leverage is introduced as a key factor for the link in our formulation since spending is constrained by liquidity not income due to spreading credit facilities. Moreover, domestic spending is no longer constrained by national income once foreign savings are available for cheap use (Brown, 2008). Sophisticated financial and marketing services create income illusion as a long-term effect on spending behaviour in OECD countries such as the USA. Consumers can use their credit limits as a way of forecasting incomes to the extent that, with access to large amounts of credit for decades, they are likely to infer that their lifetime income is permanently high, and therefore, their willingness to use credit for spending will also be high (Soman and Cheema, 2002). Such income illusion is reinforced by financial globalisation, which enters into our modelling for a deficit country such as the USA, but not for China. Individuals in China and other Asian countries cannot borrow against future income growth but must save in order to make large purchases due to their less developed financial systems.

We also provide an empirical test for cross-country differences in the inequality-saving link through panel data regressions. The estimation results turn out to support our theoretical prediction for the OECD versus Asia differences. We find evidence on financial development playing an expected role in shaping the inequality-saving links. Although research has lasted for decades, the effect of inequality on saving remains an open issue because of analytical ambiguity and mixed empirical findings. While some studies find no systematic or robust effect (Schmidt-Hebbel and Servén, 2000; Leigh and Posso, 2009), others identify a positive (Cook, 1995; Smith, 2001; Li and Zou, 2004) or a negative effect (Edwards, 1996; Malinen, 2011). This issue is now attracting renewed attention due to worsening global imbalances and the resulting financial crisis that has aroused widespread social tensions. Our study attempts to contribute to the literature by emphasising both the sharp differences in the effect of inequality on saving between surplus and deficit economies and the important implications of saving or leverage for global imbalances and financial crises.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 provides a further yet brief literature survey in relation to global imbalances and financial crises. Section 3 proposes a new theory of inequality-saving links by extending the post-Keynesian model to credit consumption that is facilitated by financial globalisation. Section 4 presents estimation results from an econometric analysis of OECD and emerging Asian economies. Section 4.1 concludes the paper.

2 Literature Review

The literature on saving and inequality is enormous. We provide a brief survey on inequality-saving links in the context of global imbalances and financial crises. Although studies for these topics in the literature have largely been evolving separately, we attempt to connect them with recent realities in a logical and orderly manner as follows. We look at deficit-country issues first.

- Decreased employment protection in favour of aggressive financial development has caused an unequal income distribution and a declining wage share in GDP in OECD countries since the 1980s (Blanchard and Giavazzi, 2003; Wolff, 2010).

- Consumer credit was expanded aggressively through financial liberalisation to replace reduced wages and prevent workers’ consumption from contracting severely, so that the drop in their consumption is less than the fall in their income (Krueger and Perri, 2006; Heathcote et al., 2010).

- Credit consumption based on asset bubbles led to a high and rising ratio of household debt to income, to a sharp decline in aggregate saving, and hence to financial fragility and serious crises when this situation became unsustainable (Iacoviello, 2008; Obstfeld and Rogoff, 2009; Kumhof and Ranciere, 2010).

- Soaring profits made possible by falling wages were not largely used as real savings for producible investment but mainly recycled as interest-bearing liquid assets backed by loans to workers for consumption, thereby depressing saving rates and heightening current account deficits (Carroll, 2000; Kumhof et al., 2012).

- Rising income inequality was followed by political interventions, which did not tackle its sources but rather delayed its consequences by promoting cheap credit for workers to protect their living standards from stagnating real wages. Legislators who represent areas with higher inequality are more likely to vote for policies that increase credit availability or make credit cheap (Bertrand and Morse, 2012). It is also observed that financial interest groups pushed through policy changes favourable to credit business expansion. Indeed, politicians are much more responsive to their high-income constituents than to low-income voters (Bartels, 2008).

- As complementary interventions, easy monetary policies and low interest rates were adopted to facilitate aggressive financialisation without considering future consequences, thus creating asset bubbles, encouraging speculative trading and making savers increasingly prefer financial over real assets (Taylor, 2009; Lowenstein, 2010).

- Economic growth was thus driven mainly by credit-based consumption and related financial service, but not by real investment or producible capital accumulation, further putting downward pressure on current account and pushing up the risk of financial crises (Skidelsky, 2009; Keys et al., 2010).

- Rising current account deficits were increasingly financed through foreign savings by promoting free capital mobility and taking advantage of the problematic international monetary system (Mussa, 2004; Roubini and Setser, 2004).

Surplus-country issues discussed in the literature are centred on several important aspects below.

- Income inequality is caused by very low real wages despite the rapidly rising labour productivity (Karabarbounis and Neiman, 2013) and contributes directly to low and falling consumption relative to fast growing national income (Gu et al., 2013). High and rising savings cannot be fully absorbed by domestic investment and have to flow out for ‘reliable’ stores of value abroad (Caballero and Krishnamurthy, 2006). Effectively, capital mobility may serve as a tool of financing to channel savings for foreign credit consumption or domestic investment use (Chan et al., 2011a).

- Under global underinvestment (Prasad et al., 2007), saving outflows help lower global interest rates further and fuel financial bubble speculation. For example, China's high savings are said to be responsible for cheap debts, housing bubbles and financial crises elsewhere in the world (Greenspan, 2009).

- Persistent trade imbalances that hinge on large saving differences between Asia (mainly China) and the West (mainly the USA) have triggered trade protectionism and exchange-rate disagreement (Lardy, 2006). While such imbalances problem is widely attributed to the ‘currency misalignment’, some authors point to economic fundamentals (i.e. saving and productivity) as a root cause of the problem (McKinnon, 2005).

The above literature survey suggests the significance of the causes and effects of inequality-saving links. Weak labour protection causes income inequality in both deficit and surplus countries in relation to their respective finance-led and export-based growth strategies. Inequality affects saving in different ways in those economies due to their differing degrees of financial development, with different implications for trade balance and financial risk. As for the problem of global imbalances, rising inequalities act as its sources through cross-country saving differences, and global financial crises emerge as its consequences. Therefore, our paper concentrates attention on different inequality-saving links across countries.

3 Theoretical Formulation

Different financial systems are perceived to have exerted differing influences on the inequality-saving link across advanced and emerging-market economies. This section formulates such cross-country differences by extending the post-Keynesian model. The key to extending this model is to incorporate the impacts of consumer credit that has differing levels of development in different countries. Such extended model provides a solid theoretical foundation for regression specifications to be conducted in the next section.1

Global imbalances are affected by cross-country differences in aggregate saving that includes public and private savings. Higher taxes increase public and aggregate savings under no Ricardian equivalence. Private saving is the sum of the corporate and household savings. There is little consensus among studies on the determinants of firm saving. Various hypotheses2 exist to explain household saving that accounts for the overwhelming share of private saving, although the results from hypothesis testing are far from conclusive. Our aggregate analysis does not distinguish between saving categories, but rather examines different patterns of saving behaviour relating to income inequality under three financial circumstances: liquidity constraint, domestic credit and foreign financing.

3.1 A Positive Inequality-saving Link under Liquidity Constraints

A positive link of saving with inequality can be derived from the traditional post-Keynesian model, though with necessary changes to incorporate useful elements from other hypotheses for saving behaviour. Consider two income groups: {B for bottom, T for top}. Group B is composed of workers with stable, low labour income, and group T consists of agents with variable, high non-labour income or super-high executive pay. Non-labour income includes property income captured by capitalists, tax revenue by governments and illegal or immoral income by public and corporate officials as widely observed in developing countries or transition economies.

Consumption is constrained by income without borrowing opportunity as in China and other parts of Asia with limited or no consumer credit. Most of income YB in group B is permanent income used for consumption CB, with a high propensity to consume: αB = CB/YB. Much of income YT in group T is transitory income ready for saving after covering consumption CT,3 with a low propensity to consume: αT = CT/YT. Then, αB > αT is postulated as usual to reflect the long-term differences in behavioural patterns between the two groups. Consumption habits are persistent under behavioural inertia.

(1)

(1)Clearly, YT/Y affects C/Y negatively under αB > αT. Thus, we have:

Proposition 1.The rate s (=S/Y) of aggregate saving S (=Y − C) increases with higher income inequality under no consumer credit.4

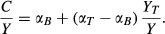

The equation 1 result is applicable to emerging Asian economies, as depicted in Figure 1. Savings in China and other Asian countries are used for investment, not consumption, owing to the underdevelopment of their financial systems in general and the lack of consumer credit in particular. Individuals must save for large purchases due to no opportunity to borrow against future income growth. Additionally, it is a state financing policy to direct national saving to manufacturing investment for trade expansion, and this financial orientation has been an important part of industrial policies and growth strategies in many Asian economies (Stiglitz, 2001). However, even massive investment in Asia such as China cannot productively absorb all its enormous saving, so surplus saving has constituted for years a substantial surplus of current account and a direct source of trade frictions with the USA and other OECD countries. The Asian exportation of surplus saving is blamed for prolonged economic problems in other countries (Greenspan, 2009).

- Note: Fifteen Asian economies are included in this plot for 2005–12. The saving rate is the average of the saving-to-GDP ratio, and its data are taken rrom the World Bank National Accounts. Income inequality is the average of the Gini index, and its data come from multiple sources such as the World Bank Databank, China's National Bureau of Statistics, Hong Kong's Census and Statistics Department, the OECD Income Distribution Questionnaire, Taiwan's Statistics Databook, and Singapore's Yearbook of Statistics.

3.2 A Negative Inequality-saving Link Due to Consumer Credit

A negative link between inequality and saving is caused by the fact that the saving of the wealthy is used not for output growth by investing firms but for increased consumption by poor households through deficit spending. This saving by the rich, after becoming consumer credit for the poor, should be viewed as consumption spending rather than domestic saving in the national income accounts. In this case, spending is constrained not by income but by liquidity, as observed in OECD countries and modelled as follows.

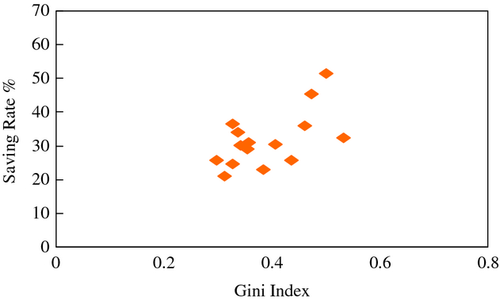

(2)

(2)Clearly, C′/Y increases with a higher ratio of YT/Y if β′T > 1 − α′T/α′B (≡ κd > 0 due to α′T < α′B).6 We thus arrive at:

Proposition 2.Higher inequality lowers the saving rate S′/Y due to consumer credit if the lending ratio is so high that a sufficient portion of saving by the rich is lent to the poor for consumption rather than to firms for investment.

If setting β′T = 0 in equation (2), our extended model reduces to equation (1) that was derived under no consumer credit. Working with αB = α′B yields CB < C′B, showing that consumption is increased with borrowing opportunities than without them even though borrowers’ consumption propensity remains unchanged. In fact, this propensity is likely to be boosted by consumer credit, so that the consumption-to-GDP ratio may expand further. In this case, κd increases with a higher propensity of α′B, that is, the top income group must raise its lending ratio to maintain the condition of β′T > κd.

The equation 2 result applies largely to the situation of OECD economies, as depicted in Figure 2. The negative role of inequality for saving is jointly driven by the two sides of the credit market. On the lending side, more of liquid assets backed by consumer loans to workers are preferred by investors as stores of value. These non-producible assets result in no job creation for indebted workers. On the borrowing side, many people borrowing against the rising value of their homes live with income illusion arising from asset bubbles, with such an illusion created by uninformative but persuasive advertisements. Even poor people optimistic about the future have developed habitual profligacy through the easy use of cheap credit under strong consumerism. Under these circumstances, spending is constrained by credit limits regardless of actual incomes, as suggested by βT > κd in our equation (2) model.7

- Note: Twenty-eight OECD countries are included in this plot for 2003–07. The saving rate is the average of the saving-to-GDP ratio and its data are collected from the World Bank National Accounts Database. Income inequality is captured by the Gini index for the population aged 18–65 and its data are collected from the OECD Income Distribution Questionnaire at http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=INEQUALITY.

The relationship between surging inequality and declining saving has a clear bearing on policy response in the USA and other OECD countries. Income inequality generates social pressure, but no intervention has been attempted to reverse it. Instead, political efforts were often made to prop up the living standards of the bottom income group through encouraging easy credit and keeping demand robust despite its falling income share (Rajan, 2010). With more saving at the top and more borrowing at the bottom, consumption inequality has increased much less than income inequality, but the domestic indebtedness of the poor and the middle class has increased substantially. The saving rate is then on the freefall as a result of domestic lending, which is directed by financial markets for consumption rather than for investment (Kumhof and Ranciere, 2010).

3.3 The Negative Inequality-saving Link Strengthened by Foreign Financing

The contribution of consumer credit to saving collapse in OECD countries was reinforced by the cross-border mobility of savings under financial globalisation. In this case, domestic spending is no longer constrained by national income as foreign saving becomes available in the long run for easy use at low costs. For example, the spread of global capital markets has enabled poorer US households to borrow more relative to their incomes for about three decades, as reported in the literature (Kumhof and Ranciere, 2010). We proceed with our modelling by considering foreign financing for consumer credit to make the analysis more realistic.

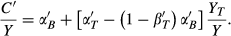

Now consider an open economy. Consumption propensity is specified as α″T = C″T/YT for group T and α″B = C″B/(YB + D) for group B, where C″B + C″T = C″ is aggregate consumption and debt D borrowed is treated again as the ‘illusive income’. Assume α″T < α″B as usual. The debt D is now borrowed from foreign sources by Df as well as from domestic savers by D″d, so that D″d + Df = D. The lending ratio is D″d/YT = β″T for group T. Denote by λ (=D/D″d ≥ 1) the ratio of total debt to domestic debt (as an index for international capital mobility), so that D = λβ″TYT, with a higher ratio λ indicating more foreign financing given D″d.

(3)

(3)If setting λ = 1 in equation (3) (i.e. zero foreign financing for domestic credit), this extended model is reduced to equation (2) that was obtained under consumer credit but with no foreign financing.

Equation 3 shows that the inequality index YT/Y affects the consumption ratio C″/Y positively and hence the saving rate s″ = S″/Y negatively if β″T > (1 − α″T/α″B)/λ (≡ κf). Since κf = κd/λ < κd under λ > 1, we know that the condition of β″T > κf for the open economy is easier to satisfy than that of β′T > κd for the closed economy.8 The economic intuition of such closed-open comparison is that the rich need not raise their lending ratio to maintain the condition of β″T > κf as the poor can borrow foreign saving to increase their consumption. Moreover, this condition becomes even weaker as κf falls with greater capital mobility λ (i.e. more foreign financing is available to facilitate domestic credit). We then establish:

Proposition 3.The negative saving-inequality link is further strengthened when more of consumer credit can be covered by foreign savings.

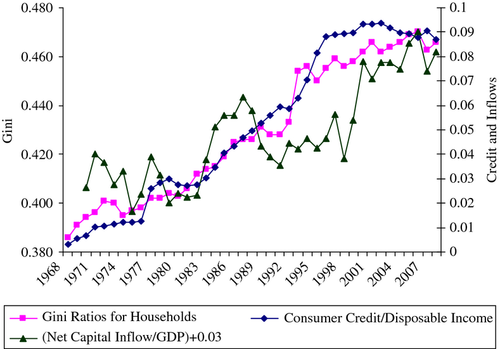

The negative inequality-saving (or positive inequality-credit) nexus is attributable to swelling financial services facilitated by international capital flows, as implied by Figure 3 for the USA. This issue received scant attention before the recent global crisis (Brown, 2008); only recently has the literature begun to establish the direct relation of rising income inequality to surging household leverage under consumer credit and foreign financing (Iacoviello, 2008). Four points are worth further discussing below.

- Note: Data on consumer credit and the Gini index come from Krueger and Perri (2006), and net capital inflows are calculated from the CEIC Database.

First, as savers’ desire to lend and households’ need to borrow increase simultaneously irrespective of national boundaries, so do both cross-border flows of funds between different income groups and the size of the financial sector. The aggressive expansion of this sector is indicated by many measures (Philippon, 2008). Second, while intermediating foreign savings makes the top income group increasingly richer, the bottom group becomes much more indebted, heightening economic inequality. Third, widespread consumer credit with foreign financing is responsible for the falling and low rate of saving, as is implied by equation (3) with ∂s″/∂λ = −β″Tα″BYT/Y < 0. When this fall starts to be perceived as unsustainable, it becomes the trigger for a financial crisis (Kumhof and Ranciere, 2010). Fourth, surging inequality renders the economy more dependent on consumption for growth, which drives down saving below investment, so that trade deficits inevitably follow and must be financed through net borrowing from foreign sources. If this situation persists, current account imbalances will keep on getting worse. While dollar depreciations are needed to reduce the US trade deficit, the fundamental change required to curb this problem is an increase in the US national saving rate (Feldstein, 2008).

Since consumption propensities are lower for the top than for the bottom income group, it follows that consumption inequality is inherently less than income inequality. With our extended models presented above, one can prove that this phenomenon is reinforced by consumer credit and that consumption inequality falls below income inequality to a larger extent if there is more foreign financing for domestic credit and if debt-to-income ratios are higher for poorer households (as has happened in the USA; see Brown, 2008). Such significant phenomenon has been documented for the USA in the literature (Kumhof and Ranciere, 2010; Tridico, 2012). On the contrary, consumption and income inequality may stay together if consumer credit is absent or limited, with strong evidence found from China (Cai et al., 2010).

4 Econometric Analysis

The above economics theoretical model shows that different financial systems make income inequality affect saving rates in different manners between OECD and Asian countries. This section performs an econometric test for such theoretical result based on panel data. Furthermore, we provide a comprehensive characterisation of empirical links between the saving rate and a broad range of potentially important saving determinants identified in the literature. We estimate a variety of panel data regressions to check for the robustness of the effects of rising inequality on aggregate saving under different financial systems.

4.1 Econometric Procedure

Three empirical issues need to be addressed in our estimation as in other similar studies (Loayza et al., 2000). First, inertia in saving rates is likely to be present in the original annual data we use; therefore, we need a dynamic specification for estimation if data are good enough in quality and availability. Second, some regressors may be jointly determined with the saving rate as the dependent variable, and we thus should control for their joint endogeneity. Third, we may need to handle the possible presence of unobserved country-specific effects correlated with explanatory variables.

To deal with these issues, we apply the GMM system estimator in dynamic panels to OECD countries with large sample size and high data quality. This estimator allows for saving inertia by including lagged values of the dependent variable as a regressor. The estimator can also be used to control for unobserved country-specific effects and potential endogeneity problems using ‘internal instruments’ based on lagged values of explanatory variables. The Sargan test is adopted to test the overall validity of these instruments. The GMM estimator retains all the information in both cross-country and time-series data.9

Unfortunately, the GMM estimator is not suitable for Asian economies due to their small sample size and limited data availability. We therefore have to compute fixed effect panel estimates after ruling out random effects models through the Hausman test. A cross-section weighted FGLS estimator is used to correct for heteroscedasticity because of large differences in size among Asian economies. We employ the panel corrected standard error methodology to compute robust estimators in both the saving and consumption regressions.

Our empirical analysis is based on a reduced-form approach encompassing a variety of saving determinants, while our attention is focused on the saving effects of inequality and finance. We attribute private consumption to a broad set of underlying factors: (i) lagged values of dependent variables; (ii) alternative indexes of income inequality; (iii) various measures of financial depth; (iv) demographic structure features; (v) income-related variables and (vi) special characteristics of different economies under consideration. All variables are expressed in logarithms with only a few inevitable exceptions.10 The dependent variable in some regressions is the ratio of private consumption to GDP, which mirrors aggregate saving because household saving takes up an overwhelming share of aggregate saving. In other regressions, the rate of aggregate saving is used as the dependent variable to check for the robustness of our estimation results.

The regressors are selected according to economic relevance as well as data availability. Their selection is reported below: (i) income inequality, characterised by the Gini index with large sample size and by the income shares of the top (0.5, 1, 5) per cent of the population; (ii) financial depth, measured by various price and quantity variables, such as the real interest rate, domestic credit to private sectors relative to GDP (denoted credit.ps), private credit supplied by depository banks and other financial institutions relative to GDP (denoted credit.do), the ratio of credit to deposits in banks, the value added of the financial sector as a share in GDP and the ratio of M2 money to GDP; (iii) demographic structure, including the old age, young age and total dependency ratios; (iv) income-related variables, represented by the level and growth of GDP per capita; and (v) the share of industrial output in GDP, reflecting preferences of Asian economies for trade expansion by building large manufacturing capacity.

The financial variables deserve more attention. The real interest rate is the only price variable used in our regressions to detect the effect of finance on saving. Higher values of quantity variables represent higher degrees of financial depth, and the first two such variables (credit.ps and credit.do) capture the access to borrowing opportunities. The ratio of credit to deposits in banks indicates the degree of leverage or viability in the whole banking system. The financial value added as a share of GDP implies the size of the financial sector in an economy. The M2-to-GDP ratio is an indicator widely used to measure the degree of financial depth in developing countries. Financial variables may enter into interaction terms to detect certain cross-effects on saving or consumption.

It is worth noting what kinds of impacts the above factors would have on saving or consumption.11 As predicted by our theory (developed earlier), the estimates for inequality coefficients in consumption regressions could be positive in OECD countries but negative in Asian nations. Moreover, financial depth would be expected to contribute positively to consumption in OECD countries, while the industrial-GDP ratio should have a negative influence on consumption in emerging Asia.

The expected signs for other coefficient estimates are supposed to be very similar to those in previous studies relevant to saving decisions. The estimated coefficient on the lagged dependent variable would be anticipated to have a positive value to reflect habit formation. The overall impact of real interest rates on consumption could be positive if their income effect outweighs their substitution effect. Dependency ratios must affect consumption positively in all economies in consistency with the life-cycle hypothesis. The positive saving effects of income levels or growth rates of per capita GDP would be expected to arise in all regressions as established in intertemporal consumption theory.

4.2 Data Description

Most information used in our empirical analysis is the cross-country, time-series macroeconomic annual data from the CEIC Database and the World Development Indicators documented by the World Bank. Our financial data draw from the Financial Development and Structure 2009 supplied by the World Bank. Income distribution data we use are collected from the World Top Income Database and the UNU-WIDER World Income Inequality Database. These panel data sets are heavily unbalanced, especially for Asian economies, with the number of time-series observations varying considerably across countries.

Twenty-three OECD countries are involved in our regressions after excluding potential outliers.12 Instead of using long time-series data that span several decades (Cook, 1995; Schmidt-Hebbel and Servén, 2000; Smith, 2001; Li and Zou, 2004), our empirical analysis focuses only on the period from 2000 to 2007. This is a special period of time, during which the developed world witnessed a dramatic run-up in income inequality, an accelerating pace of leverage hike or debt accumulation, a rapid expansion of the financial sector and a sharp decline in the saving rate (Glick and Lansing, 2010; Kumhof and Ranciere, 2010; McKinsey Global Institute, 2010). These changes led to worsening global imbalances and eventual financial meltdown in OECD economies.

Twelve Asian countries are included in our empirical study.13 Many of them, widely recognised as ‘miracle’ economies in emerging Asia, have achieved strong output growth facilitated by high savings, but experienced income inequality deterioration for a few decades. The determinants of their consumption ratios and saving rates are investigated in our regressions for the period between 1990 and 2007, which saw their active participation in economic globalisation and financial integration with the Western world.

4.3 Estimation Results

Our discussion about estimation results is organised around core specifications displayed in Table 1, which is followed by Tables 2 and 3 reporting some variants of regressions. We resort to many regression specifications to check for the robustness of testing for the empirical validity of our theory proposed earlier. The set of regressors designed for OECD in our estimation is not exactly the same as, but slightly different from, that for Asian economies to account for differences in socioeconomic policy and structure between the two groups of countries.

| Regressor | OECD (GMM) | Asia (FE) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Lagged private consumption ratio | 0.311*** (20.402) | 0.300*** (12.999) | 0.391*** (36.442) | |||

| Gini | 0.068*** (3.473) | 0.046** (1.99) | 0.027*** (2.724) | −0.132*** (−4.472) | −0.137*** (−5.051) | −0.137*** (−4.400) |

| Young dependency ratio | 0.075*** (2.616) | |||||

| Old dependency ratio | 0.445*** (3.514) | 1.099*** (5.645) | 0.286*** (4.014) | 0.086*** (2.779) | ||

| Total dependency ratio | 0.157*** (4.925) | 0.114*** (3.579) | ||||

| GDP per capita. level | −0.366*** (−11.82) | −0.489*** (−4.212) | −0.217*** (−11.284) | |||

| GDP per capita. growth | −0.0004 (−0.742) | −0.002*** (−2.480) | −0.002*** (−2.797) | |||

| Industrial output/GDP | −0.141*** (−4.484) | −0.177*** (−5.224) | −0.239*** (−6.464) | |||

| Credit. ps | 0.101*** (10.068) | −0.040*** (−4.113) | ||||

| M2/GDP. growth | −0.046 (−1.228) | |||||

| Real interest rate | 0.001** (2.131) | |||||

| Financial value added/GDP | −0.027*** (−2.801) | |||||

| Bank credit/bank deposit | 0.173** (2.444) | |||||

| Credit. do | 0.067*** (12.111) | |||||

| Number of observations | 102 | 102 | 102 | 165 | 169 | 129 |

| Cross sections included | 19 | 19 | 20 | 12 | 12 | 11 |

| S.E. of regression | 0.023 | 0.028 | 0.022 | 0.043 | 0.046 | 0.036 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.964 | 0.963 | 0.985 | |||

| J-statistic and p-value | 17.074 [0.252] | 16.989 [0.257] | 19.013 [0.213] | |||

| Hausman test and p-value | 13.733 [0.033] | 14.329 [0.014] | 42.558 [0.000] | |||

Notes:

- (i) ‘FE’ stands for fixed effects. Numbers of observations and cross sections are influenced by the availability and quality of inequality data.

- (ii) t-Statistics in parentheses, and heteroscedasticity corrected for FE models.

- (iii) Asterisks ***, ** and * indicate significance at 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively.

| Regressor | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lagged private consumption ratio | 0.364*** (59.874) | 0.329*** (26.927) | 0.558*** (3.474) | 1.005*** (4.381) | 0.678*** (3.323) | 0.284*** (6.904) | 0.556*** (10.189) |

| Lagged Gini | 0.038** (2.159) | 0.040** (2.264) | 0.115*** (4.06) | 0.135** (7.784) | |||

| Lagged income share of top 5% | 0.152** (2.14) | ||||||

| Lagged income share of top 0.5% | 0.132** (2.488) | ||||||

| Lagged income share of top 1% | 0.079* (1.847) | ||||||

| Old dependency ratio | 0.823*** (2.998) | 1.459** (2.179) | 0.749*** (3.119) | ||||

| Total dependency ratio | 0.094* (1.777) | 0.098* (1.661) | 0.485 (1.526) | 0.358*** (6.868) | |||

| GDP per capita. level | −0.159*** (−8.527) | −0.254*** (−9.411) | −0.798*** (−4.94) | −0.955*** (−4.434) | −0.806*** (−2.529) | −0.089* (−1.908) | −0.156*** (−9.739) |

| Lagged credit. ps | 0.084*** (3.747) | 0.044* (1.831) | 0.094 (1.32) | 0.080 (1.576) | 0.068*** (6.456) | ||

| Lagged bank credit/bank deposit | 0.123*** (3.039) | ||||||

| Lagged credit. do | 0.068*** (4.336) | ||||||

| Credit. do × Gini | 0.009*** (3.365) | ||||||

| Credit. ps × Gini | 0.011*** (2.608) | ||||||

| Credit. ps × income share of top 5% | 0.023*** (3.789) | ||||||

| Credit. ps × income share of top 0.5% | 0.006*** (2.765) | ||||||

| Credit. ps × income share of top 1% | 0.005** (2.263) | ||||||

| Bank credit/bank deposit × Gini | 0.018*** (4.325) | ||||||

| Credit. ps × real interest rate | −0.0005*** (6.456) | ||||||

| Number of observations | 101 | 101 | 61 | 58 | 61 | 101 | 69 |

| Cross sections included | 20 | 19 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 19 | 18 |

| S.E. of regression | 0.023 | 0.023 | 0.021 | 0.03 | 0.021 | 0.024 | 0.017 |

| J-statistic and p-value | 17.988 [0.207] | 18.601 [0.136] | 6.933 [0.327] | 7.983 [0.157] | 3.746 [0.711] | 15.883 [0.255] | 15.928 [0.195] |

Notes:

- (i) t-Statistics are in parentheses.

- (ii) The asterisks ***, ** and * indicate the significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively.

| Regressor | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lagged Gini | −0.081** (−2.457) | −0.105*** (−3.623) | −0.113*** (−3.468) | −0.076** (−2.010) |

| Total dependency ratio | 0.114*** (3.321) | 0.164*** (4.974) | 0.177*** (5.748) | |

| Young dependency ratio | 0.168*** (6.302) | |||

| Old dependency ratio | 0.130*** (3.841) | |||

| GDP per capita. growth | −0.001** (−2.253) | −0.002** (−2.549) | −0.002*** (−2.954) | −0.001 (−1.053) |

| Industrial output/GDP | −0.090*** (−3.393) | −0.163*** (−4.959) | −0.188*** (−5.828) | −0.165*** (−5.864) |

| Real interest rate | 0.016 (1.569) | |||

| Credit. ps × Gini | −0.011*** (−4.292) | |||

| (M2/GDP. growth) × Gini | −0.020** (−1.945) | |||

| (Financial value added/GDP) × Gini | −0.005* (−1.785) | |||

| Real interest rate × Gini | −0.004 (−1.526) | |||

| Number of observations | 164 | 169 | 144 | 156 |

| Cross sections included | 12 | 12 | 11 | 12 |

| S.E. of regression | 0.043 | 0.047 | 0.037 | 0.048 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.961 | 0.960 | 0.984 | 0.968 |

| Hausman test and p-value | 9.341 [0.096] | 15.914 [0.007] | 39.342 [0.000] | 29.815 [0.000] |

Notes:

- (i) t-Statistics in parentheses are heteroscedasticity corrected.

- (ii) The asterisks ***, ** and * indicate the significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively.

In Table 1, we report estimation results from basic regressions for the private consumption ratio in OECD and Asian economies based on unbalanced panel data. The Sargan statistics find no evidence against the validity of instruments specified for GMM system estimation. Note that the key measure of financial depth in our regressions is domestic credit to private sectors relative to GDP (credit.ps) for both OECD and Asian countries, with the growth of M2 money relative to GDP used only for emerging Asia. Let us interpret the results recorded in columns 1 and 4 first and then compare them with those listed in other columns and obtained under alternative measures of financial depth.

Different inequality-consumption links can be made clearer through comparison between OECD and Asian economies, so our discussion below revolves around such a comparison. The lagged private consumption ratio in OECD countries has a positive and significant coefficient estimate, whose size reveals the degree of persistence in consumption habit over time and is observed to be large in these mature economies.

The coefficient on the inequality variable carries a significant estimate, which is found to be positive for OECD yet negative for Asian economies. A rise in the Gini index is observed to boost consumption in OECD countries but depress it in Asia. This empirical observation is consistent with the assertion of our theory proposed earlier. Previous findings by other authors are similar to ours, in that consumption is not dampened by widening income gaps in advanced countries (Heathcote et al., 2010).

Demographic factors we estimate have the same effect as predicted by the life-cycle hypothesis. Our coefficient estimates for dependency ratios are significant in all economies. The impact of old dependency on consumption is strong in OECD countries with ageing societies for long,14 where the private consumption ratio increases with a rising old dependency ratio. For Asian economies with younger population, young dependency has an impact on consumption similar to that of old dependency, where a rise in young (/old) dependency leads to an increase in consumption.

We find that the consumption ratio is negatively affected by income levels in OECD countries but by income growth in emerging Asia, with most of these effects being statistically significant. The different effects of income levels and growth rates between the two groups of countries coincide with the fact that income growth is low in OECD economies but high in Asia while OECD's income level is higher than Asia's. It seems that the Keynesian theory is still valid in the West while the life-cycle hypothesis works better in Asia. Consumption growth usually lags behind income growth in Asia due to serious inequality. For example, China's household consumption as a percentage of GDP has actually fallen since 2001 despite its average 10 per cent GDP growth per year for decades.

Financial depth (measured by credit.ps) is found to significantly affect consumption in a positive (/negative) way for OECD (/Asian) countries. When domestic credit to private sectors rises relative to GDP, private consumption relative to GDP grows in OECD countries, but falls in Asian economies (columns 4 and 5). This finding reflects the fact that the financial sector is oriented to encourage consumption via cheap, easy credit in developed countries but to promote investment and industrialisation in developing countries. This fact is corroborated in Asian economies by their significantly negative relationship between the ratio of private consumption to GDP and the share of industrial output in GDP. An increase in such a share is observed to be associated with a decline in the private consumption ratio.

Similar results emerge from alternative measures of financial depth used for OECD economies. Private credit by depository banks and other financial institutions relative to GDP (credit.do) and the ratio of credit to deposits in banks are used for estimation (columns 2 and 3). These two measures are also associated positively and significantly with private consumption in OECD countries, while the significance and signs of estimated coefficients on other regressors remain unchanged. The two measures do not exist in most of Asian economies, but data are available for the growth rate of the M2-to-GDP ratio and the share of financial value added in GDP. Both these variables, thus used as alternative measures of financial depth for Asia, are found to impact negatively on private consumption (columns 6 and 7). This result arises from the emphasis of Asian finance on industrial activity rather than on consumer credit, so that Asian people have to spend out of their own income or previous savings under liquidity constraints.

Private consumption in Asia is positively related to the real interest rate (column 7), seemingly suggesting the dominance of income over substitution effects. A more realistic interpretation may exist for this positive relation. In some Asian economies, like China, the interest rate on bank deposits is often capped by governments to a very low level, even below the inflation rate, to encourage manufacturing investment for trade expansion. However, the lack of social safety net tends to force people to diversify away from uncertainty about future income and policy by consuming less and saving a larger fraction of their income. This precautionary motive for saving arises in China despite low or even negative real returns on deposited money, thereby resulting in a positive association of consumption with interest rates (Nabar, 2011; Lardy, 2012).

Tables 2 and 3 are presented to show the robustness of our empirical results using alternative indicators for income inequality and by incorporating into the regressions the effects of interactions between inequality and finance.15

We take the results of Tables 2 and 3 as supportive of our core regression findings in Table 1. The new results for OECD and Asian economies are summarised separately for Tables 2 and 3.

In Table 2, when income shares of the top (0.5, 1, 5) per cent of population are used as inequality indicators, the positive inequality-consumption link still holds for OECD countries. The estimated coefficients on these indicators appear to be larger in size than those on the Gini index. Column 3 reveals that a rise in the income share of the top 5 per cent group would increase the private consumption ratio because the wealthy in this group can lend more to poor people for consumption through credit markets. The impacts on private consumption from other regressors, such as demographic, financial and income-related variables, are similar to those in the Table 1 basic regressions. Moreover, when income inequality is allowed to interact with financial depth, we find that their positive effects on private consumption are intensified significantly in OECD countries because all interaction terms carry positive coefficient estimates. The negative sign of the estimated coefficient on (credit.ps × real interest rate) suggests that a lower real interest rate strengthens the positive effect of credit on consumption because people would be encouraged to use more credit for consumption as their cost of borrowing falls.

In Table 3, for most Asian economies, data on top groups’ income shares are not available. We thus continue to rely on the Gini index for estimation and let it interact with financial variables to examine the robustness of our empirical results. The new results for five variables (the Gini index, dependency ratios, income growth, the share of industrial output in GDP and the real interest rate) are consistent with those of the Table 1 basic regressions in terms of estimates’ signs and significance. Moreover, the significantly negative coefficient estimates for credit.ps × Gini, (M2/GDP.growth) × Gini and (financial value added/GDP) × Gini imply that financial systems in Asia reinforce the negative linkage between inequality and consumption. An additional interaction term shows that the negative effect of inequality on consumption becomes weaker with a lower real interest rate in emerging Asia.

Table 4 summarises the basic regressions for the aggregate saving rate and is used to check for the robustness of our empirical results. Clearly, the estimation results from saving regressions in Table 4 are largely consistent with those from consumption regressions in Table 1. The Table 4 results are briefly interpreted as follows.

| OECD (GMM) | Asia (FE) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Lagged aggregate saving rate | 0.708*** (6.958) | 0.419** (2.518) | 0.502*** (10.035) | |||

| Gini | −0.416*** (−3.363) | −0.464*** (−3.121) | −0.179** (−2.619) | 0.203*** (3.231) | 0.195*** (2.857) | |

| Lagged Gini | 0.188*** (2.804) | |||||

| Young dependency ratio | 0.0294 (0.230) | −0.092 (−1.144) | −0.300*** (−4.242) | −0.390*** (−6.643) | −0.350*** (−6.004) | |

| Old dependency ratio | −0.533* (−1.831) | −2.392*** (−3.507) | −0.507*** (−2.902) | −0.501*** (−8.955) | −0.471*** (−7.218) | −0.417*** (−6.601) |

| GDP per capita. level | 0.652*** (5.128) | 1.110*** (3.932) | 0.676*** (9.160) | |||

| GDP per capita. growth | 0.002 (1.431) | 0.003*** (2.625) | 0.004*** (2.562) | |||

| Industrial output/GDP | 0.341*** (5.417) | 0.404*** (5.447) | 0.270*** (4.619) | |||

| Credit. ps | −0.0917*** (−3.0377) | 0.152*** (5.302) | ||||

| Financial value added/GDP | −0.281* (−1.779) | 0.086* (3.588) | ||||

| Credit. do | −0.184*** (−5.390) | |||||

| (M2/GDP. growth) × Gini | 0.052** (2.117) | |||||

| Number of observations | 102 | 78 | 102 | 163 | 142 | 169 |

| Cross sections included | 20 | 15 | 20 | 12 | 11 | 12 |

| S.E. of regression | 0.052 | 0.076 | 0.044 | 0.079 | 0.069 | 0.081 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.948 | 0.975 | 0.951 | |||

| J-statistic and p-value | 13.452 [0.491] | 10.494 [0.398] | 15.705 [0.332] | |||

| Hausman test and p-value | 28.557 [0.000] | 16.395 [0.012] | 14.929 [0.021] | |||

Notes:

- (i) t-Statistics in parentheses are heteroscedasticity corrected.

- (ii) The asterisks ***, ** and * indicate the significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively.

- Income-related regressors. The observed impact of income inequality on aggregate saving is significantly consistent with our theoretical prediction made earlier, for the sign of the estimated coefficient on the Gini ratio is positive in Asia but negative in OECD economies. As shown by coefficient estimates, aggregate saving is positively associated with income levels across OECD countries but with income growth among Asian economies.

- Finance-related regressors. As will be shown in our theoretical model, relaxing credit constraints on consumption depresses aggregate saving in OECD countries. Indeed, credit.ps, credit.do and the share of financial value added in GDP each have a negative and significant estimate. This result provides a strong view on the saving effect of financial liberalisation as in previous studies: over-financialisation is not good for growth but detrimental to saving in OECD countries (Tridico, 2012).

By contrast, financial depth indicators (credit.ps, (M2/GDP) growth × Gini, and financial value added as a share in GDP) have positive and significant estimates in Asia, suggesting the role of finance in facilitating aggregate saving rather than promoting consumption. A significantly positive coefficient estimate is obtained for the industrial share in GDP, and this result reflects the fact that much of increased saving in Asia has been channelled into investment for industrialisation and trade expansion.

- Demographic regressors. Consistent with the life-cycle hypothesis, the estimated effects of dependency ratios on saving rates are mostly negative in both groups of countries, although they vary in estimate size and statistical significance.16

For OECD countries with high demographic maturity aggravated by low birth rates, the estimated coefficient on their old dependency ratio is substantially larger than that on their young dependency ratio, indicating that the positive saving effect of their high-income levels might be dampened by their ageing population structure.

5 Conclusion

This paper conducts both a theoretical and an empirical examination for the role of financial development in determining differences in inequality-saving links between OECD and Asian countries. Our approach extends the post-Keynesian model by incorporating income illusion that is created by finance-led speculative growth. Our regression shows that the estimated links between inequality and saving are significantly different between those economies, with the role of finance for such different links turning out to be statistically detectable. Our main findings along with their policy implications are summarised below.

The recent global crisis is perceived to hinge on worsening global imbalances, which in turn were engendered by large saving differences between deficit and surplus economies. The saving rate is related to income inequality negatively in deficit economies with overdeveloped capital markets able to finance substantial credit consumption. On the contrary, saving is linked to inequality positively in surplus economies with weak financial systems providing limited or no consumer credit. While income inequality has the same root causes in both types of economies where workers’ bargaining power for income sharing is weaker than investors’, this problem has met with different policy responses. Consumer credit was expanded in deficit countries to prevent workers’ living standards from falling, while consumption relative to GDP was left declining in surplus countries due to credit constraints facing workers.

Differing consequences have emerged from those different policies. In the deficit countries, aggressive financial liberalisation, though succeeding in keeping workers’ living standards from dropping, has transformed higher income inequality into higher domestic indebtedness and eventually larger external deficits. While aggregate demand was stimulated artificially, real aggregate supply has been held back by a slower accumulation of producible capital as investors prefer portfolio over direct investment. All those problems, once perceived to be unsustainable, jointly became a trigger for the crisis. In the surplus countries, higher inequality lowers workers’ income share, while driving down their consumption relative to income growth since they cannot borrow against future income due to low financial development. The domestic wealthy thus have to export their goods and deploy their increased incomes in financial assets abroad, thereby resulting in a current account surplus and strong foreign protectionism against it.

Policy implications boil down to a long-term serious policy measure aimed at alleviating income inequality in all countries. Only this policy can stop global imbalances from further deterioration and hence reduce future vulnerability to global crises. Theory and evidence established in our study imply that income inequality must be controlled in both the financially advanced and less developed countries. With inequality lessened, the former countries may overcome deficits through a higher saving rate while the latter can limit surpluses through a lower saving rate. There would be no alternative in the long run to dealing directly with the problem of income inequality. The lesson learned from the three-decade-long OECD experience is that financial liberalisation can only buy time but may store up trouble for later with a much larger debt problem (Kumhof et al., 2012).

In the deficit countries, there are many options for inequality reductions but no easy solution to the inequality problem. For example, employment protection legislation can be strengthened for the benefit of labour, and tax codes can be adjusted at the expense of capital. Yet, these options would drive away investment under competition from emerging markets. A more realistic reform is to restrain capital markets from excessive risk taking by stepping back from financial deregulation. In the surplus countries, reducing the ‘financial market imperfections’ is a short-sighted policy response to global imbalances. Liberalising loans to workers without addressing the inequality problem itself would only increase domestic indebtedness and might heighten financial fragility even though doing so could mitigate global imbalances. An effective measure is to substantially increase labour income, so that domestic demand can ultimately become a powerful driver for sustainable economic growth.