Staff perspectives on barriers and enablers to implementing alternative source plasma eligibility criteria for gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men

Funding information: Canadian Blood Services

Abstract

Background

Canadian Blood Services introduced new eligibility criteria that allows some sexually active gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (gbMSM) to donate source plasma, marking a significant change from time-based deferral criteria. We aimed to identify potential barriers and enablers to implementing the new criteria from the perspective of donor center staff.

Study Design and Methods

We conducted Theoretical Domains Framework-informed interviews with staff from two source plasma donation centers in Canada.

Results

We completed 28 interviews between June 2020 and April 2021. Three themes representing eight domains captured key tensions. Valuing inclusive eligibility criteria: staff support inclusive criteria; many were concerned the new criteria remained discriminatory. Investing in positive donor experiences: staff wished to foster positive donor experiences; however, they worried gbMSM donors would express anger and disappointment regarding the new criteria, staff would experience unease over using stigmatizing criteria and convey nonverbal cues of discomfort, and recurring plasma donors may behave inappropriately. Supporting education, training, and transparency of eligibility criteria: participants believed providing in-person training (i.e., to explain criteria rationale, address discomfort, practice responding to donor questions) and ensuring donors and the public were well-informed of the upcoming changes would improve implementation.

Discussion

Participant views emphasize the importance of supporting staff through training and transparent communication to optimize the delivery of world-class equitable care for a new cohort of donors who have previously been excluded from plasma donation. Findings inform which staff supports to consider to improve implementation as policies continue to shift internationally.

1 INTRODUCTION

International blood and plasma donation policies for gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (gbMSM: we chose the term gbMSM in consultation with stakeholders while acknowledging the limitations of MSM language)1 are highly contested and have spurred debates regarding how to uphold equity principles while meeting regulatory safety standards.2-5 Several countries have now eased restrictions from lifetime bans to progressively shorter time-based deferrals2 without compromising safety.6, 7 Calls for more inclusive and equitable criteria,3, 7 and evidence suggesting deferral periods are no longer necessary,7, 8 have led Canadian Blood Services (CBS) to explore further changes to blood and plasma policies. In May 2021, CBS submitted a proposal to Health Canada, the regulatory body, to change the criteria for source plasma donation9 given the low risk of transmission of blood-borne infections in plasma-derived products. The pilot plasma program represented the first time sexually active gbMSM would be able to donate plasma.

Changing policies to include sexually active gbMSM requires that staff implement the new screening criteria and address donor and public questions regarding the changes. Staff are further tasked with providing donors with deferral explanations that are based on criteria that may be viewed as offensive and discriminatory.10, 11 Despite the critical role staff play in implementing criteria changes, recruiting plasma donors,12 fostering positive donor experiences,13 providing donor education, and encouraging return donations,13-15 few studies have documented staff perspectives regarding eligibility changes and how they are impacted by evolving donation policies. We, therefore, sought to identify possible barriers and enablers to implementing new plasma criteria from the perspective of donor center staff in Canada prior to the regulatory approval of the new program.

2 METHODS

This study is part of a larger study involving other groups of stakeholders.16 Our approach is rooted in integrated knowledge translation, a form of research co-production that emphasizes collaboration with knowledge users who are in positions of power to act on the findings of the research.17 The research activities were largely conducted by members external to Canadian Blood Services. That said, we involved scientists and staff from Canadian Blood Services to ensure our research activities remained relevant and useful despite shifting policies and to facilitate ongoing knowledge translation to more rapidly disseminate our research findings within the organization.

2.1 Methodological approach

Complex interventions, like eligibility criteria changes, can be enhanced by conducting theory-informed feasibility assessments that aim to identify possible barriers and enablers to implementation.18 We used the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF), a broad and versatile framework that synthesizes constructs from 33 behavior change theories into 14 domains (see Table 1),19-21 to identify factors that could be addressed to optimize the implementation of the pilot plasma program. We used the TDF as a guiding framework to conduct qualitative interviews and data analysis.

| Domain | Description |

|---|---|

| Knowledge | An awareness of the existence of something (including knowledge of condition/scientific rationale) |

| Skills | An ability or proficiency acquired through practice |

| Social/professional role and identity | A coherent set of behaviors and displayed personal qualities of an individual in a social or work setting |

| Beliefs about capabilities | Acceptance of the truth, reality, or validity about an ability, talent or facility that a person can put to constructive use |

| Optimism | The confidence that things will happen for the best or that desired goals will be attained |

| Beliefs about consequences | Acceptances of the truth, reality, or validity about outcomes of a behavior in a given situation |

| Reinforcement | Increasing the probability of a response by arranging a depending relationship, or contingency, between the response and a given stimulus |

| Intentions | A conscious decision to perform a behavior or a resolve to act in a certain way |

| Goals | Mental representations of outcomes or end states that an individual wants to achieve |

| Memory, attention and decision processes | The ability to retain information, focus selectively on aspects of the environment and choose between two or more alternatives |

| Environmental context and resources | Any circumstance of a person's situation or environment that discourages or encourages the development of skills and abilities, independence, social competence, and adaptive behavior |

| Social influences | Those interpersonal processes that can cause individuals to change their thoughts, feelings, or behaviors |

| Emotion | A complex reaction pattern, involving experiential, behavioral, and physiological elements, by which the individual attempts to deal with a personally significant matter or event |

| Behavioral regulation | Anything aimed at managing or changing objectively observed or measured actions |

| Nature of behaviora | Direct experience/past behavior including routine, automatic, or habitual behavior |

- a From the initial set of 12 domains included in the TDF.18

2.2 Study context: donor screening and proposed criteria

At the time of this study, Canadian Blood Services operated 30 permanent collection sites, eight of which were source plasma collection sites. There were three types of source plasma clinic models running at different collection sites during this time: three source plasma-only clinics, three clinics where source plasma and transfusible plasma products were collected, and two large volume source plasma clinics. These two large volume source plasma clinics, located in London (Ontario) and Calgary (Alberta), were the donation centers that would be implementing the pilot expanded eligibility program for gbMSM approved by Health Canada (the national regulator). Staff at these two large volume donor centres were interviewed as they were the only ones poised to be implementing the new eligibility criteria for gbMSM.

Source plasma donor screening practices in Canada involve a self-administered donor health questionnaire that can be completed online or in-center. Trained nursing staff review donor responses and ask additional questions in a private screening booth according to a donor-screening manual.

At the time of this study, the criteria required a three-month deferral period for all sexually active gbMSM. The proposed pilot plasma program was set to take place in two donation centers in London, Ontario and Calgary, Alberta. In this pilot, donors who respond “yes” to being a man who has had sex with another man would be asked two additional questions in the screening booth by a nurse. The additional questions were: (1) “In the last three months, have you had a new sexual partner?” and (2) “In the last three months, have you and your partner only had sex with each other?”

Donors with one exclusive sexual partner for at least 3 months, and who met other standard eligibility criteria, would be able to donate source plasma as often as every 6 days. Units would be quarantined for 60 days until a second donation tested negative for transfusion-transmissible infections.

2.3 Recruitment strategy

We invited donor center staff involved in applying and discussing eligibility criteria with prospective donors (e.g., supervisors, nurses) at the two pilot sites to participate in semistructured interviews. We worked with donor center management to advertise our study (e.g., information sessions, emails, flyers) and schedule interviews so they did not interfere with scheduled staff shifts. Staff could participate in an interview during paid time or were offered a $50 gift card to participate during non-working hours.

2.4 Interviews

Interview guides were developed to address “who needs to do what when”22 and followed guidance20 for conducting TDF-informed studies (see Supplement S1). Interviews were conducted by EV, a post-doctoral fellow with qualitative expertise, and two research coordinators, EG and GC, with backgrounds in social work and social psychology, respectively. All interviewers were trained in qualitative TDF methodology. Interviewers explained the goals of the study and the proposed plasma criteria changes (see Supplement S1). Interviewers took notes during and after interviews capturing key ideas, tone, and reflections.

2.5 Analysis

GC and EG conducted an inductive content analysis23 on three transcripts to generate initial codes and discuss different perspectives on the data. They developed a codebook where inductive codes were categorized according to TDF domains. During this initial stage, disagreements were resolved by categorizing codes into all proposed domains. GC then conducted a directed content analysis23 guided by the TDF20 and codebook using NVivo version 11. This involved labeling interview excerpts with codes and sorting codes into TDF domains. Codes were refined by comparing data within and across codes to determine how codes were similar, different, and related to each other. Codes relating to similar topics were grouped into within-domain categories. Categories were compared across domains to generate overarching descriptive themes.

2.6 Sample size

Sample size was determined based on informational power where sample size decisions are based on the scope of the study, the specificity of participant experiences, the quality of dialogue between interviewers and interviewees, and the analytic strategy.24 We assessed the quality of the data as it was collected and analyzed to gauge whether we had sufficient information to develop our themes and inform our TDF analysis.

2.7 Ethics

This study received ethics approval from the Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board and the CBS Research Ethics Board. All participants provided consent prior to participating in interviews.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Participants

Approximately 100 staff members were approached, 30 expressed interest, and 28 participated in an interview between June 2020 and April 2021. Participants' median age was 51 (IQR = 42–56) and the median number of years spent in their role was 11 (IQR = 6–14). We chose not to report data on gender distribution to maintain participant anonymity. Eighteen interviewees participated during paid staff time and 10 participated on their own time. Sixteen participants used video conferencing software and 12 were interviewed by phone. Interviews lasted a median of 51 min (IQR = 56–75) and were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Participants were invited to review their transcripts, make edits, and provide additional feedback on their accounts. Five participants provided edits on their transcripts.

3.2 TDF domains and overarching themes

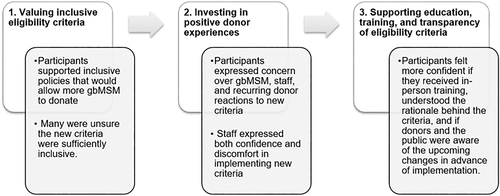

Nine domains (knowledge, skills, social/professional role/identity, beliefs about capabilities, beliefs about consequences, goals, social influences, emotion, and behavior regulation) were relevant for understanding and addressing barriers and enablers to implementing the new criteria. These domains are highlighted in this paper in italics and parenthesis adjacent to relevant findings. Domain-specific barriers and enablers were synthesized into three overarching themes: (1) Valuing inclusive eligibility criteria, (2) investing in positive donor experiences, and (3) supporting education, training, and transparency of eligibility criteria (see Figure 1). Themes, key domains, and example quotes are presented in Table 2. A comprehensive list of TDF domains and quotes is provided in Supplement S2.

| Category | Key TDF domains | Quotesa |

|---|---|---|

| Theme 1: Valuing inclusive eligibility criteria | ||

| Staff views on new eligibility criteria | Beliefs about consequences/emotion | “So I guess for me, I can see that it's a stepping stone. It may not be a stepping stone that we all agree with, but at least it's a stepping stone. If this is the beginning, not the end, then sure. I can accept that. I don't celebrate it but I can accept it.”—Staff #18 |

| Beliefs about consequences/emotion | “This first question, I have a problem with. It's discriminatory all the way through. It's basically their sexual behavior compared to a straight man's sexual behavior… Then you're going to hold their blood in quarantine? They're a leper? It's what you're calling them, a leper…It's dehumanizing. It is. I find that question completely dehumanizing.” Staff #4 | |

| Goals | “I'm still hoping at a certain point, these orientation specific questions will be eliminated and, you know, persons who are bi or gay or in an open relationship will have the ability to come in and be asked the exact same questionnaire as everyone.”—Staff #26 | |

| Social influences | “…maybe I am more open-minded because I have this experience [connection to LGBTQ2SIA+ community] … So maybe that's why my mind is more open… Like I am all for the inclusion…” Staff #12 | |

| Social and professional role | “I believe that we all should be treated as people, regardless. Yeah, 100 percent. We should all be accepting of everybody.”—Staff #17 “But the thing I'm most worried about is, my biggest fear would be somebody coming in and feeling like they were singled out because they are a man who has sex with men who's participating in this plasma program. I really hope that we can just make that as seamless and that it's no different than any other donor, and that's how it happens.” Staff #8 |

|

| Theme 2: Investing in positive donor experiences | ||

| Anticipated gbMSM responses | Beliefs about consequences | “The fact that they're actually allowed to give, I think they'll be ecstatic. To me, I think they'll be so happy. Even if we did screw up on something, or said the wrong thing or said it the wrong way”—Staff #23 “It also feels challenging too, because likely these donors will be new to CBS, and this will be their very first experience with us and with the questionnaire. Then to be further discriminated against in these secondary questionnaires when they already know that their unit is being treated differently, I just feel like that isn't that helpful.”—Staff #14 |

| Knowledge/emotion | “So as a first time donor, it's usually more overwhelming. Knowing that you're MSM coming in, and in the past traditionally you haven't been able to donate, I think it's stressful. I think that individual is going to be stressed, or they're going to be on guard because they think that you're going to pick a fight with them.”—Staff #25 | |

| Anticipated donor responses | Beliefs about consequences | “They're going to say something, without thinking about what their saying … I can see that happening with a few of our [donors]… that don't take change very well”—Staff #19 “I never encountered a situation where someone felt uncomfortable that we were easing those restrictions. It was more why aren't we easing them more.”—Staff #16 |

| Anticipated staff responses | Social and professional role/skills | “… we have to remember to always be compassionate and understanding and accepting of who they are and not to make them feel like they're different. So I think we have a role ourselves to be professional and to just address it as “it's just the way it is right now with our criteria” … [and] it is criteria that has been set by Health Canada and our medical team.”—Staff #22 |

| Beliefs about capabilities | “I would feel exactly the same as I would feel for anybody else that's donating. I would be totally confident and comfortable and I wouldn't do anything differently…”—Staff #20 “…to me, it doesn't make any sense, and I feel they could poke holes in it very quickly, and then I would be left with not being able to answer their questions.” Staff #24 |

|

| Emotion | “Well, I don't want to make them feel uncomfortable, and I feel bad when somebody makes the effort to come out and do something good and it seems like I'm questioning. I'm not questioning their worth, but it feels like it. They feel like they're not good enough, so to speak.”—Staff #21 “Personally, I don't think we should have to. That's my personal feeling. I don't think they should have to be asked. It's just me. You don't ask the heterosexual person … we don't ask them. Would you feel comfortable asking the questions? Yeah. I'd do it. I'd do it but personally, I'd have to put my personal feelings aside.”—Staff #23 |

|

| Beliefs about consequences | “I think that our nurses are fairly professional when it comes to asking basic questions. Again, they may be a little bit more uncomfortable with the multiple sex partners question, and I'm just thinking some staff if they got the answer, yes, how would they facially react? You know, it's not always, they don't need to answer, but would their face change? You know, I think that it would be a more difficult response.”—Staff #27 | |

| Theme 3: Supporting education, training, and transparency of eligibility criteria | ||

| Rationale for eligibility criteria | Knowledge | “I think questions regarding the why is it still a three-month deferral period? Why is there any deferral period at all, if you're not in a monogamous relationship, because it's not the same as the regular whole blood donors that come in. We aren't asking them that question, so why are we asking men having sex with men this question? I think that's going to be the biggest question that might come out.”—Staff #15 “I think from a training perspective, we really need to have a solid rationale around why we're quarantining, the length of quarantine time, the specifics around that, and really have it scientifically supported rather than just, there's almost a fear-mongering versus scientifically supported, database driven, kind of criteria.”—Staff #5 |

| Training to prepare for criteria changes | Beliefs about capabilities | “I'm a nurse and as long as we're educated from our employer how to respond to perhaps some of the, you know… and we're going to get some pushback. If you could educate us so that we could educate them and maybe have some language available to help the situation, then, I'm all for it.”—Staff #28 |

| Skills | “It would be nice with a criteria change like this… to be a little bit formal and maybe have more classroom setting training where there's more room for discussions, so people can voice any concerns, any questions that they may have so we can answer those together in a room and make sure that they have all the tools that they feel like they need to implement the change.”—Staff #9 | |

| Knowledge | “I think I would also want to know what do these men think too, that are coming into this program. Are they okay with this, are they hesitant? Are they asking for this?”—Staff #24 “I think a little bit because it is a sensitive topic and I wouldn't want to say the wrong thing to offend them and not make them feel welcome. So that's why like for me, it would be really important to have talking points that have been maybe developed with someone from that population.” Staff #1 |

|

| Transparent communication with donors and the public | Behavior regulation | “I think just making sure that CBS put out a lot of information for this change. But just making sure that they've put out information, that they've answered, maybe hold like a Q&A prior to changing the criteria… so that when they're coming to us it's not like they have all these questions and I don't have the answers. I think it would just make it a smoother process for everybody if they made sure that there's lots of information and questions answered prior to the criteria change. It's going to make it comfortable.”—Staff #2 |

- a Participant numbers were assigned at random.

3.2.1 Valuing inclusive eligibility criteria

Staff held varied perspectives on the new criteria (beliefs about consequences, emotion). For some, the new screening questions represented “a step in the right direction” and generated excitement over long awaited changes. Others expressed ambivalent views noting the changes were positive but insufficient (“new criteria are a half measure”). For others, the new criteria were disappointing, frustrating, and harmful (“I find that question completely dehumanizing”). Many believed the criteria needed to change to gender neutral, behavior-based screening where all donors would be asked the same screening questions (goals). Some participants (n = 12) volunteered information about their personal connections to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, two spirit, intersex, asexual and other sexual orientations and gender identities not expressly named (LGBTQ2SIA+) communities (e.g., friends, family, or themselves identifying as members). They suggested their views were informed by their lived experience and conversations they had within their networks about the stigmatizing impact of these policies on LGBTQ2SIA+ communities (social influences).

Participants believed “treating everybody the same” was an important professional value yet the new criteria called for a differential screening process and a quarantine requirement (social/professional role). This led some participants to believe that introducing gbMSM donors into donation centers would be optimal if it did not further “single them out.” For some participants, this specifically included refraining from posting symbols of allyship (e.g., Pride flags, rainbows) as this was viewed as differential treatment. For others, symbols of allyship were viewed as inappropriate as long as the eligibility criteria continued to differentiate gbMSM from other donors (“Pride imaging is important, but I wonder if it kind of misses the mark…”). A few staff indicated they would be more open to symbols of allyship if they knew that gbMSM donors would appreciate them.

3.2.2 Investing in positive donor experiences

Participants who had experience screening gbMSM donors shared that eligibility conversations were often personal, sensitive, and emotionally challenging. Donors often expressed anger, disappointment, sadness, shame, rejection, and embarrassment when faced with a deferral decision, and staff in turn felt empathy, sadness, frustration, and shame (emotion). These past experiences and staff awareness over gbMSM donors' feelings of exclusion contributed to participant concerns over how donors might respond to the new screening questions. Some participants expressed hope that the new screening criteria would be viewed positively while others feared the new screening questions and quarantine process would be perceived as offensive, discriminatory, and disappointing (beliefs about consequences, knowledge).

Participants described the recurring donor (e.g., long-time donors who provide weekly donations) group as highly committed, knowledgeable regarding the donation process, vocal, and interested in socializing with other donors. However, staff expressed concerns that recurring donors may express negative views about gbMSM (“bigotry is going to be the biggest problem”) and the change in criteria (beliefs about consequences). Though some suggested “intolerance will not be tolerated”, many indicated they would need to prepare for possible altercations. Others believed recurring donors would be supportive of the change in criteria as they are generally supportive of encouraging others to donate (beliefs about consequences). Regardless, participants expected recurring donors to be inquisitive and emphasized the need for more information and communication strategies to address potentially difficult questions and commentary from recurring donors.

Participants believed fostering positive staff-donor interactions was important for communicating to gbMSM that they were welcome in donation centers (“maybe after their first experience here they would notice that it's… nonjudgmental and they're welcome”). Staff described using a variety of strategies to manage challenging eligibility discussions with gbMSM. These included apologizing, empathizing, expressing gratitude, and staying calm. They also described more informational approaches like referring to the criteria and deferral manuals, explaining the criteria rationale and regulator oversight, and emphasizing that changes are ongoing (skills). Staff discussed how they valued being knowledgeable, nonjudgmental, and composed in their roles (social/professional role). Though most participants felt confident and capable using the new criteria and welcoming new gbMSM donors, they noted areas where staff would likely benefit from targeted training and other supports (beliefs about capabilities).

Staff discussed the possibility of experiencing discomfort while conducting eligibility screenings (emotion). Many acknowledged feeling uneasy either because they viewed the criteria as stigmatizing or because they worried that gbMSM donors would feel offended by the criteria. Others described feeling ashamed and embarrassed to use criteria that were seen as discriminatory and suggested they would have to compartmentalize their feelings to maintain their professional composure. A few participants expressed concerns that staff would share their opinions on the new criteria (e.g., disagreeing with criteria) if they were not provided with scripted messages.

Participants also expressed concerns over how their colleagues may unconsciously react when implementing the new criteria (beliefs about consequences). For example, staff may hold unconscious biases and may communicate discomfort through nonverbal cues. Staff also noted that the infrequency of gbMSM donor screenings may contribute to “fumbling” through screening and deferral processes which may lead donors to feel nervous or judged. Others expressed confidence in staff's ability to manage their opinions and biases and ensure all donors were treated with respect and dignity.

3.2.3 Supporting education, training, and transparency of eligibility criteria

Staff wished to understand the scientific rationale behind the new screening criteria and quarantine requirement and wished to know more about the evidence base supporting the criteria change (see Table 3 for example questions from staff and Supplement S3 for a comprehensive list of questions participants raised) (knowledge). For example, many noted that a sexual activity question had previously been asked of all donors and was then removed. Staff expressed confusion at the decision to “bring back” sexual behavior questions only for gbMSM. Staff further wanted to understand the rationale so that they could better respond to donor questions (“how do I explain to a donor…when I don't personally [understand]”) and justify the new criteria. Some participants wanted statistics to share with donors to demonstrate the criteria were necessary and not an example of “fear mongering.”

| Topic | Questions |

|---|---|

| Transmissible infections | 1. Why are gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (gbMSM) considered a “higher risk” group? What are the rates of HIV/HBV transmissibility among other groups? 2. What is the window period during which HIV and other STIs are undetectable? 3. How are window periods determined? |

| Proposed screening questions | 1. Why bring back sexual activity questions for gbMSM donors only when they were previously removed for all donors? 2. What is the research evidence that supports the use of the new screening questions? 3. Why are screening questions/quarantine process necessary if plasma fractionation process eliminates bacteria and viruses? |

| Quarantine process | 1. What is the scientific rationale for the 60-day quarantine period? 2. Why not include all gbMSM, regardless of their recent sexual history, if plasma units will be quarantined anyway? |

Staff indicated that implementing the new criteria would require more comprehensive training than would typically be provided with other criteria and process changes. Staff suggested they would feel more confident discussing the new criteria with donors if they were provided with in-person training in advance of implementation (beliefs about capabilities). Training would explain the rationale behind the screening criteria, provide staff with CBS-endorsed speaking points to address donor concerns, and review process oriented instruction (skills). Most participants suggested that interactive training where staff could voice questions and concerns, role play difficult eligibility discussions, and practice asking the new screening questions and responding to donor concerns using CBS-endorsed speaking points would be beneficial (skills, knowledge). Some suggested that having gbMSM representatives speak with staff would help them appreciate their perspective and better understand how they wished to be addressed (e.g., appropriate language) (knowledge).

Staff indicated it would be important for CBS to communicate the changes to eligibility criteria to all donors and the public (behavior regulation). Staff believed preparing gbMSM donors for what to expect would help attenuate harm that may result from engaging with offensive criteria by allowing gbMSM to self-defer if ineligible or decide whether they were willing to go through the screening process. A few staff indicated that informing and educating existing and recurring donors and the public would also help mitigate possible negative reactions from other donors.

4 DISCUSSION

We aimed to identify barriers and enablers to staff implementing new eligibility criteria for plasma donation. Staff believed they were capable of implementing criteria changes though many voiced concerns over managing difficult eligibility discussions. Staff varied on whether they believed the new criteria were sufficiently inclusive and most staff appreciated receiving in-person training to better prepare them to respond to donor questions.

Our study is the first to document the views of donor center staff in Canada regarding changing plasma policies. Our study complements findings from a study exploring staff views on the transition to a 1-year deferral period for gbMSM in the United States.25 Participants in both studies supported more inclusive policies and valued training to improve their confidence implementing new criteria. Our study adds to these findings by surfacing the sources of staff discomfort that include concerns over offending gbMSM, unease with enforcing discriminatory criteria, and worry over recurring donor reactions to the changing criteria. Importantly, our findings demonstrate that even when staff are supportive of inclusive criteria, they require education, training, and institutional supports (e.g., communication) to ensure they can effectively implement new criteria.

Staff perspectives on the new eligibility criteria also correspond with gbMSM views on blood and plasma policies. Though some gbMSM believed shortened deferral periods (e.g., from 12 to 3 months) and other alternative eligibility criteria (e.g., quarantines) were an improvement,10, 11, 26 many believed the alternatives were insufficient for addressing longstanding homophobic policies that continue to exclude and stigmatize gbMSM.10, 11, 26 Staff similarly expressed positive views when comparing the new screening process to the older, more restrictive criteria while others felt the new criteria were still discriminatory. Staff in our study were aligned with gbMSM views that a more equitable policy would ask all donors the same screening questions and would have a strong scientific rationale.26, 27

Participants in this study were older and experienced in their roles. We consulted with our stakeholder partners and confirmed that the age and level of experience of staff that we interviewed was fairly representative of staff working at permanent collection sites such as the large volume source plasma clinics. Permanent site jobs are highly valued due to better hours resulting in greater numbers of senior staff employed at these sites. Younger less experienced staff usually work in mobile sites.

Participants in our study valued treating all donors the same but feared symbols of allyship would further differentiate gbMSM from other donors. Similarly, being treated with discretion despite differential processes was reported as a facilitator to plasma donation among gbMSM.10 However, symbols of allyship were not viewed as differential treatment but as indicators of a welcoming space by gbMSM (unpublished data). This difference between staff and gbMSM views of symbols of allyship points to the importance of distinguishing between equity (distributing resources and supports based on need to achieve fairness of outcome) and equality (everyone is treated the same). It also highlights the significance of engaging directly with staff and members of affected communities, when preparing for eligibility changes that are steeped in histories of exclusion.

Participants also wished to learn more about gbMSM experiences and to hear directly from community members regarding their views on the changing criteria. In keeping with participants' desire to be well-prepared to greet and welcome gbMSM donors, gbMSM in turn, have indicated that having qualified staff who are sensitive to their experiences see them through the donation process would enable them to donate.10 Creating opportunities for staff to learn about the experiences, perceptions, and preferences of gbMSM donors may help align strategies for creating welcoming spaces.

Participant suggestions for improving rollout also correspond with donor perspectives and behavior. Participants in our study believed that informing gbMSM donors about the new screening criteria would be preferable so that they may self-defer if ineligible. Donor views on sexual behavior based screening similarly suggest that providing donors with information about what questions to expect could mitigate discomfort and allow donors to self-defer.28 Avoiding deferrals may be an important strategy given that deferrals are experienced negatively, in center (vs over the phone) deferrals are associated with lower retention rates,26 and that deferrals decrease motivation to return, especially for new donors.30, 31 Thus, clearly communicating criteria changes to reduce the chances of being deferred in the first place may contribute to better donor experiences.

Staff also expressed a desire to understand the rationale behind screening criteria so that they could better explain deferral decisions and respond to donor questions and concerns. Participants believed being able to speak knowledgably about the criteria was an indicator of professionalism and a tool for managing difficult eligibility discussions. However, they did not feel they had access to adequate information and resources to confidently explain the rationale behind the new criteria. Donor experiences with deferrals suggest that the quality and quantity of information provided may impact donor emotions. This in turn can predict retention29 and may encourage donors to rebook appointments when quality information is provided in center at the time of the deferral.32 These findings emphasize the importance of training staff to effectively communicate policy rationales while attending to donor emotions.

4.1 Strengths and limitations

One strength of this study is the emphasis on theory. By identifying which theoretical domains are implicated in addressing staff barriers and enablers to implementing new criteria we can determine which evidence-based strategies (e.g., behavior change techniques)33, 34 are likely to better support staff.

One limitation is that we did not collect demographic information beyond age and gender. Almost half of the sample volunteered information regarding their connection to LGBTQ2SIA+ communities which likely impacted the importance they placed on inclusive policies. This may be due to a self-selection bias in our sample whereby participants meaningfully differed from staff at the centres who chose not to participate. Participants may have been more interested in the change of criteria; they may have also differed in their inclination for self-disclosure and to share their views and experiences within an employment context.35 Future research would do well to consider how staff's social positions impact their views on changing blood and plasma policies.

A second limitation is that some staff participated on their own time while others participated during paid hours. Some staff were interviewed over the phone while others were interviewed using video conferencing software. Though we did not identify any distinct patterns in the data, it is possible that those who participated on their own time were more motivated to share their views and those who used video conferencing software were more susceptible to social desirability biases.

A final limitation is that staff were asked about one criteria change concerning gbMSM plasma donors amidst continuously evolving criteria. However, the concerns raised by staff are relevant for ongoing discussions of changing blood policies in Canada and internationally. For example, sexual behavior-based screening has been implemented in the UK36 and is being considered in Canada.9 This involves asking questions about anal sex which may be uncomfortable for some donors28, 37 and may be experienced as differential treatment of gbMSM even if the questions are asked of all donors.28 Others have suggested that staff may require cultural competency training when using individual risk assessments that include sensitive questions.38 Our findings speak to the importance of surfacing and addressing staff concerns and discomfort prior to criteria changes to ensure staff are provided with appropriate supports to bolster confidence and preparedness.

5 CONCLUSION

Donor center staff support inclusive blood donation policies and wish to see the criteria evolve toward gender neutral screening. While staff described discomfort and uncertainty in addressing donor concerns, they also reported being dedicated to providing respectful and inclusive donation experiences. When implementing more inclusive criteria, it will continue to be important to support staff through ongoing training, education, and communication to ensure they feel prepared to provide all donors with an optimal donation experience.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jonni-Lyn VanDeursen and Cori Anderson for their assistance in scheduling interview participants and all our participants for their willingness to share their thoughts and experiences with us.

FUNDING INFORMATION

We received funding from the Canadian Blood Services MSM Research Grant Program and MSM Plasma Program, funded by the federal government (Health Canada) and the provincial and territorial ministries of health. The views herein do not necessarily reflect the views of Canadian Blood Services or the federal, provincial, or territorial governments of Canada.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

TB-F, DL, MiG, SO, and DD work for Canadian Blood Services who administered the grant. MaGe works for Héma-Québec, another blood operator. The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.