Evaluating the appropriateness of fresh frozen plasma transfusions in two tertiary teaching hospitals

Abstract

Background

Despite efforts to standardise practice using evidence-based guidelines, fresh frozen plasma (FFP) remains the blood component most frequently prescribed inappropriately. This study assessed the appropriateness of FFP transfusion in two tertiary teaching hospitals and analysed the characteristics of appropriate and inappropriate transfusions.

Methods

Patients who had undergone FFP transfusion between October and December 2022 at two tertiary teaching hospitals were retrospectively analysed. Only the initial FFP transfusion data were analysed for each patient. Patient characteristics; laboratory test results, including prothrombin time, international normalised ratio, and activated partial thromboplastin time; and the association of FFP transfusion with various factors were examined. Sub-therapeutic dosing was defined as the transfusion of ≤2 units of FFP. FFP transfusions were classified into eight groups based on a classification algorithm to determine their appropriateness.

Results

In total, 584 FFP transfusions (2301 units) were analysed, with 42.1% involving subtherapeutic dosing. FFP transfusions were performed in the intensive care unit (ICU; 30.5%), general ward (24.8%), operating room (21.1%), and emergency room (22.9%). Overall, 51.5% of FFP transfusions were deemed appropriate, with significant variations being observed between the hospitals (Hospital B vs. Hospital A: 73.2% vs. 35.3%). Inappropriate FFP transfusions were associated with a higher INR, with 73.4% of them being associated with severe bleeding and/or surgery.

Conclusions

In conclusion, 40.6% of FFP transfusions were deemed inappropriate in the present study owing to failure to meet laboratory criteria. The present study provides valuable insights into the optimisation of plasma transfusion practices and emphasises the requirement for institution-specific management.

1 INTRODUCTION

Fresh frozen plasma (FFP) transfusion has been performed for the management of patients with deficiency of specific plasma proteins or coagulation factors. Notably, FFP transfusion has also been performed to prevent or treat active bleeding in patients with abnormal coagulation parameters. Evidence-based guidelines set forth to enhance and standardise plasma transfusion practice1-7 cover a wide range of clinical settings; nevertheless, variations in practice persist owing to uncertainty regarding evidence-based indications.8

Inappropriate administration of FFP has been frequently reported.7 Notably, 33.9–77.7% of plasma transfusions are suboptimal in terms of indication and/or dosage.9-14 Inappropriate plasma transfusion can increase the risk of adverse transfusion reactions such as allergic reactions, infectious complications, hemolysis, transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO), and transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI).15, 16 Furthermore, inadequate FFP transfusion may lead to the unnecessary consumption of FFP, an irreplaceable donor-derived resource.

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the appropriateness of FFP transfusions in two tertiary teaching hospitals and analyse the characteristics of appropriate and inappropriate transfusions to address these challenges and provide valuable insights into the optimisation of plasma transfusion practices.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Data collection

The electronic medical records of patients who had undergone FFP transfusions between October and December 2022 at two tertiary teaching hospitals in South Korea were retrospectively analysed. One FFP unit was defined as 320 mL or 400 mL of FFP. The FFP units administered in this study comprised plasma derived from whole blood of male donors frozen within 6 h of phlebotomy. All FFP units were produced by the South Korean Red Cross. Only data pertaining to the initial FFP transfusion were included for each patient. Patients aged <20 years were excluded. Furthermore, patients who had undergone plasma exchange were also excluded as this study focused solely on FFP transfusions.

Patient characteristics, including age, sex, department, location of FFP transfusion, and the amount of red blood cells (RBCs) and plasma transfused, were analysed. In addition, pre- and post-transfusion prothrombin time (PT), international normalised ratio (INR), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), and fibrinogen were also examined. A sub-therapeutic dose was defined as ≤2 units of FFP.2, 9, 17

The pre-transfusion INR, aPTT, and fibrinogen levels were defined as the values recorded within 24 h of initiating transfusion. The post-transfusion INR, aPTT, and fibrinogen levels were defined as the values recorded within 24 h of the end of the transfusion.

FFP transfusions were analysed based on the requirement for massive transfusion, surgery/invasive procedures, severe bleeding, protein C/S or anti-thrombin III (ATIII) deficiency, and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), as well as their association with RBC transfusion. The administration of ≥10 units of RBCs within 24 h was defined as massive transfusion. A decline in haemoglobin level by 20 g/L within 24 h or the transfusion of a single unit of RBCs was defined as moderate bleeding. A decline in haemoglobin of >20 g/L within 24 h or the transfusion of 2–9 units of RBCs within 24 h, excluding cases of massive transfusion, was defined as severe bleeding. The transfusion of FFP units within 24 h before or after the transfusion of RBCs was defined as FFP transfusions associated with RBC transfusion.

2.2 Classification of the indications for FFP transfusion

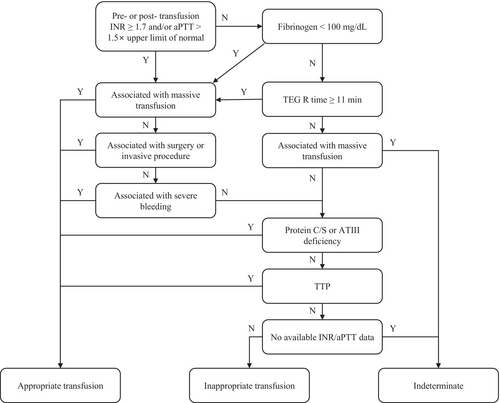

FFP transfusion was categorised as appropriate, indeterminate, or inappropriate and classified into the following eight groups using a classification algorithm (Figure 1)1, 4, 12, 18: the massive transfusion, surgery/invasive procedure, severe bleeding, protein C/S or anti-thrombin III deficiency, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, unavailable INR/aPTT data, fibrinogen, and TEG data pre- or post-transfusion, massive transfusion with unmet laboratory criteria, and inappropriate groups.

Inappropriate transfusion was defined using a cut-off value of 1.5 for INR in previous studies; however, a threshold of 1.7 was adopted in this study in accordance with the South Korean national transfusion guidelines,18 which may have influenced the FFP transfusion practices at Hospitals A and B.

The massive transfusion group comprised patients who had received massive transfusion within 24 h before or after FFP transfusion. The surgery/invasive procedure group comprised patients who had received FFP transfusion within 24 h before or after a surgical or invasive procedure. The severe bleeding group comprised patients who experienced severe bleeding within 24 h before or after FFP transfusion.

Laboratory results that did not meet any of the following criteria were deemed unsatisfactory: (i) pre- or post-transfusion INR of ≥1.7, (ii) aPTT of >1.5× the upper limit of normal, (iii) fibrinogen levels of <100 mg/dL, or (iv) TEG R time of ≥11 min.

The initial classification was based on an algorithmic hierarchy. Cases involving massive transfusion and severe bleeding were included in the massive transfusion group. However, further analysis of inappropriate FFP transfusions was conducted by classifying the cases as ‘Severe bleeding ONLY,’ ‘Surgery/invasive procedure ONLY,’ and ‘Both.’

2.3 Ethical statement

The Institutional Review Boards of the Pusan National University Hospital, Busan, Korea (Approval No. 2402-037-136) and Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital, Yangsan, Korea (Approval No. 55-2024-021) approved the study protocol. The requirement for obtaining informed consent was waived owing to the retrospective study design and the use of anonymised clinical data.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Categorical variables, presented as counts and percentages, were analysed using the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test when >25% of the expected frequencies were<5. Continuous variables, presented as means ± standard deviations, were analysed using Student's t test for normally distributed data and the Mann–Whitney U test for non-normally distributed data. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests were used to assess normality. Statistical significance was set at a two-tailed p value of <0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using the R Statistical Software (v4.1.3; R Core Team, 2021). Line art and graphs were generated using Microsoft PowerPoint (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and the R Statistical Software using the survminer package (version 0.4.9).

3 RESULTS

A total of 584 FFP transfusions (2301 units), comprising 334 transfusions (893 units) in Hospital A and 250 transfusions (1408 units) in Hospital B, were performed (Table 1). The average number of units transfused per FFP transfusion was 3.9 ± 4.7 units. The average number of units transfused in Hospital B was significantly higher than that in Hospital A (5.6 ± 6.3 vs. 2.7 ± 1.1, p < 0.001). Sub-therapeutic dosing and single-unit FFP transfusion accounted for 42.1% (246/584) and 5.5% (32/584) of all transfusions (data not shown). Significant differences were observed between the hospitals in terms of the distribution of transfusion frequency among departments (p < 0.001). The highest proportion of FFP transfusions were performed in the Department of Emergency Medicine in both hospitals.

| Overall | Hospital A | Hospital B | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transfusion data | ||||

| Total number of FFP transfusions | 584 | 334 | 250 | |

| Total number of FFP units transfused | 2301 | 893 | 1408 | |

| Transfused FFP units per transfusion | 3.9 ± 4.7 | 2.7 ± 1.1 | 5.6 ± 6.3 | <0.001 |

| FFP transfusion involved with RBC transfusion | 425 (72.8) | 245 (73.4) | 180 (72.0) | 0.260 |

| Transfused RBC units per FFP transfusion | 2.4 ± 2.3 | 2.6 ± 2.3 | 2.3 ± 2.4 | <0.001 |

| FFP transfusion involved in massive transfusion | 73 (12.5) | 47 (14.1) | 26 (10.4) | 0.184 |

| Location of FFP transfusion | 0.014 | |||

| ICU | 178 (30.5) | 106 (31.7) | 72 (28.8) | |

| General ward | 145 (24.8) | 72 (21.6) | 73 (29.2) | |

| Emergency room | 134 (22.9) | 89 (26.6) | 45 (18.0) | |

| Operation room | 123 (21.1) | 63 (18.9) | 60 (24.0) | |

| Procedure site | 3 (0.5) | 3 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Outpatient | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Patient demographics | ||||

| Number of patients | 584 | 334 | 250 | |

| Male sex | 379 (64.9) | 223 (66.8) | 156 (62.4) | 0.274 |

| Age | 64.6 ± 15.9 | 63.4 ± 15.7 | 66.3 ± 15.4 | 0.042 |

| Department (10 most frequently involved departments) | <0.001 | |||

| Emergency medicine | 181 (31.0) | 120 (35.9) | 61 (24.4) | |

| Gastroenterology | 71 (12.2) | 44 (13.2) | 27 (10.8) | |

| General surgery | 64 (11.0) | 27 (8.1) | 37 (14.8) | |

| Haematology and oncology | 47 (8.1) | 25 (7.5) | 22 (8.8) | |

| Pulmonary and allergy | 42 (7.2) | 15 (4.5) | 27 (10.8) | |

| Neurosurgery | 39 (6.7) | 31 (9.3) | 8 (3.2) | |

| Cardiology | 39 (6.7) | 16 (4.8) | 23 (9.2) | |

| Cardiovascular thoracic surgery | 37 (6.3) | 20 (6.0) | 17 (6.8) | |

| Urology | 12 (2.1) | 6 (1.8) | 6 (2.4) | |

| Trauma surgerya | 12 (2.1) | 12 (3.6) | – | |

- Note: Data are presented in n (%) or mean ± SD.

- Abbreviations: FFP, fresh frozen plasma; ICU, intensive care unit; RBC, red blood cell; SD, standard deviation.

- a Department of trauma surgery exists only in Hospital A.

Appropriate transfusions accounted for 51.5% (301/584) of all transfusions (Table 2). Notably, 7.9% (46/584) and 40.6% (237/584) of the transfusions were deemed indeterminate and inappropriate, respectively. Significant differences were observed between the hospitals in terms of the appropriateness of FFP transfusions. In Hospital A, 35.3% and 54.2% of transfusions were deemed appropriate and inappropriate, respectively. The corresponding rates in Hospital B were 73.2% and 22.4%, respectively. Statistically significant differences were observed between the hospitals in terms of the distribution of appropriate, indeterminate, and inappropriate FFP transfusions (p < 0.001). Surgery/invasive procedures and severe bleeding were the most common indications for appropriate FFP transfusions in Hospitals B and A, respectively.

| Indications | Overall | Hospital A | Hospital B | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appropriate | 301 (51.5) | 118 (35.3) | 183 (73.2) | <0.001 |

| Massive transfusion | 33 (5.7) | 18 (5.4) | 15 (6.0) | |

| Surgery/invasive procedure | 164 (28.1) | 30 (9.0) | 134 (53.6) | |

| Severe bleeding | 64 (11.0) | 55 (16.5) | 9 (3.6) | |

| Protein C/S or anti-thrombin III deficiency | 40 (6.8) | 15 (4.5) | 25 (10.0) | |

| Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Indeterminate | 46 (7.9) | 35 (10.5) | 11 (4.4) | |

| No INR/aPTT, fibrinogen, and TEG data pre- or post- transfusion | 36 (6.2) | 25 (7.5) | 11 (4.4) | |

| Massive transfusion with unmet laboratory criteria | 10 (1.7) | 10 (3.0) | 0 (0) | |

| Inappropriate | 237 (40.6) | 181 (54.2) | 56 (22.4) |

- Note: Data are presented in n (%).

- Abbreviations: aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; FFP, fresh frozen plasma; INR, international normalised ratio; TEG, thromboelastography.

Following the exclusion of indeterminate FFP transfusions (‘unavailable INR/aPTT, fibrinogen, and TEG data pre- or post-transfusion’ and ‘massive transfusion with unmet laboratory criteria’), 1365 and 671 units of FFP were administered across 301 appropriate and 237 inappropriate transfusions, respectively (Table 3). Notably, the proportion of inappropriate FFP transfusions was higher than that of appropriate transfusions in the departments of Emergency Medicine, Haematology and Oncology, Neurosurgery, and Trauma Surgery.

| Classification | Overall | Hospital A | Hospital B | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appropriate | Inappropriate | Appropriate | Inappropriate | Appropriate | Inappropriate | |

| Transfusion data | ||||||

| Total number of FFP transfusions (% among total FFP transfusions) | 301 (51.5) | 237 (40.6) | 118 (35.3) | 181 (54.2) | 183 (73.2) | 56 (22.4) |

| Total number of FFP units transfused (% among total FFP transfusion units) | 1365 (67.0) | 671 (33.0) | 329 (41.8) | 459 (58.2) | 1036 (83.0) | 212 (17.0) |

| Transfused FFP units per transfusion | 4.5 ± 5.1 | 2.8 ± 1.7 | 2.8 ± 1.1 | 2.5 ± 1.0 | 5.7 ± 6.3 | 3.8 ± 2.8 |

| FFP transfusion involved with RBC transfusion | 199 (66.1) | 167 (70.5) | 72 (61.0) | 125 (69.1) | 127 (69.4) | 42 (75.0) |

| Transfused RBC units per FFP transfusion | 2.3 ± 2.5 | 2.1 ± 1.9 | 2.7 ± 2.7 | 2.0 ± 1.7 | 2.0 ± 2.2 | 2.5 ± 2.2 |

| Location of FFP transfusion, n (%) | ||||||

| ICU | 103 (34.2) | 68 (28.7) | 47 (39.8) | 53 (29.3) | 56 (30.6) | 15 (26.8) |

| General ward | 76 (25.2) | 63 (26.6) | 20 (16.9) | 46 (25.4) | 56 (30.6) | 17 (30.4) |

| Emergency room | 66 (21.9) | 61 (25.7) | 25 (21.2) | 57 (31.5) | 41 (22.4) | 4 (7.1) |

| Operation room | 55 (18.3) | 42 (17.7) | 25 (21.2) | 22 (12.2) | 30 (16.4) | 20 (35.7) |

| Procedure site | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Outpatient | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Patient demographics | ||||||

| Number of patients | 301 | 237 | 118 | 181 | 183 | 56 |

| Male sex | 203 (67.4) | 148 (62.4) | 85 (72) | 117 (64.6) | 118 (64.5) | 31 (55.4) |

| Age | 66.3 ± 14.9 | 63.0 ± 16.6 | 66.3 ± 14.3 | 61.7 ± 16.6 | 66.3 ± 15.4 | 66.9 ± 16.0 |

| Department (10 most frequently involved departments) | ||||||

| Emergency medicine | 84 (27.9) | 78 (32.9) | 36 (19.9) | 68 (37.6) | 48 (26.2) | 10 (17.9) |

| Gastroenterology | 41 (13.6) | 30 (12.7) | 18 (9.9) | 26 (14.4) | 23 (12.6) | 4 (7.1) |

| General surgery | 46 (15.3) | 15 (6.3) | 14 (7.7) | 10 (5.5) | 32 (17.5) | 5 (8.9) |

| Haematology and oncology | 21 (7.0) | 24 (10.1) | 7 (3.9) | 16 (8.8) | 14 (7.7) | 8 (14.3) |

| Pulmonary and allergy | 27 (9.0) | 11 (4.6) | 9 (5.0) | 4 (2.2) | 18 (9.8) | 7 (12.5) |

| Neurosurgery | 16 (5.3) | 17 (7.2) | 9 (5.0) | 16 (8.8) | 7 (3.8) | 1 (1.8) |

| Cardiology | 46 (15.3) | 14 (5.9) | 7 (3.9) | 9 (5.0) | 15 (8.2) | 5 (8.9) |

| Cardiovascular thoracic surgery | 22 (7.3) | 13 (5.5) | 7 (3.9) | 5 (2.8) | 15 (8.2) | 8 (14.3) |

| Urology | 20 (6.6) | 4 (1.7) | 13 (7.2) | 3 (1.7) | 7 (3.8) | 1 (1.8) |

| Trauma surgerya | 3 (1.0) | 8 (3.4) | 3 (1.7) | 8 (4.4) | – | – |

- Note: Data are presented in n (%) or mean ± SD.

- Abbreviations: FFP, fresh frozen plasma; ICU, intensive care unit; RBC, red blood cell; SD, standard deviation.

- a Department of trauma surgery exists only in Hospital A.

Sub-therapeutic dosing accounted for 42.1% (246/584) of all FFP transfusions, corresponding to 35.9% (108/301), 50.2% (119/237), and 41.3% (19/46) of appropriate, inappropriate, and indeterminate transfusions, respectively (data not shown). Subtherapeutic dosing accounted for 49.8% (149/299) of all transfusions in Hospital A, corresponding to 43.2% (51/118) and 54.1% (98/181) of appropriate and inappropriate transfusions, respectively. Subtherapeutic dosing accounted for 34.1% (78/239) of all transfusions in Hospital B, corresponding to 31.1% (57/183) and 37.5% (21/56) of appropriate and inappropriate transfusions, respectively (data not shown).

Fifteen, nine, one, and seven single-unit FFP transfusions were administered in the ICU, general ward, operating room, and emergency room, respectively. Among these, 12, three, and 17 were classified as appropriate, indeterminate (all associated with massive transfusion but without meeting laboratory criteria), and inappropriate, respectively. Hospital-specific analysis revealed that among the 22 single-unit FFP transfusions performed in Hospital A, 14 (63.6%) were classified as inappropriate. Among the 10 single-unit transfusions performed in Hospital B, three (30.0%) were classified as inappropriate.

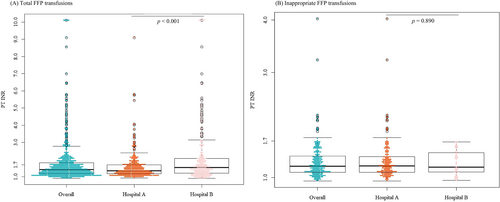

Figure 2 presents the pre-transfusion INR results for total (Figure 2A) and inappropriate FFP transfusions (Figure 2B). The mean overall pre-transfusion INR was 1.81 ± 1.3 (N = 565, range: 0.92–10.1), with the INR being ≥1.7 in 31.7% (N = 179) of cases. The mean pre-transfusion INR for inappropriate FFP transfusions was 1.3 ± 0.3 (N = 223, range: 0.94–4.02), with only 5.8% (N = 13) meeting or exceeding the cut-off value of 1.7. The pre-transfusion INR for total FFP transfusions in Hospital A was statistically significantly lower than that in Hospital B (mean: 1.57, range: 0.94–9.1 vs. mean: 2.1, range: 0.92–10.1, p < 0.001). However, no statistically significant difference was observed in terms of the INR for inappropriate FFP transfusions (mean: 1.31, range: 0.94–4.02 vs. mean: 1.28, range: 0.95–1.68, p = 0.890). Notably, no case of inappropriate FFP transfusion in Hospital B had an INR ≥1.7. The application of an INR threshold of ≥1.5 revealed that 36.3% (212/584) of FFP transfusions, corresponding to 50.9% (170/334) in Hospital A and 16.8% (42/250) in Hospital B, were classified as inappropriate (data not shown).

Figure 3 presents the indications for inappropriate FFP transfusions, including those associated with RBC transfusions. Figure 3A–C show the indications for overall inappropriate FFP transfusions, as well as those at Hospital A and Hospital B, respectively. Figure 3D–F depict the indications for overall inappropriate FFP transfusions involving RBC transfusions, as well as those at Hospital A and Hospital B, respectively. Severe bleeding and/or surgery/invasive procedures accounted for 73.4% (174/237) of inappropriate FFP transfusions: These transfusions initially did not meet the laboratory criteria but were further connected to severe bleeding or surgery/invasive procedures. Seventeen of the remaining 63 inappropriate transfusions met the laboratory criteria but did not fall into any indication group according to the classification algorithm, whereas 46 did not meet the laboratory criteria and were not classified into any indication group (data not shown).

4 DISCUSSION

The present study revealed that 40.6% (237/584) of FFP transfusions involving 671 units, corresponding to 54.2% in Hospital A and 22.4% in Hospital B, were classified as inappropriate. The rates of inappropriate FFP transfusions vary across studies. For instance, a multicenter study involving 2590 adult in-patients who received 6088 plasma transfusions reported that 34.8% of transfusions were performed without adequate indications.9 Tinmouth et al. reported that 28.6% of 573 requests for 2012 units of FFP were inappropriate according to the usage criteria.12 Similarly, a retrospective study conducted in India in 2022 revealed that 51.8% of 5922 FFP transfusions were deemed inappropriate according to established transfusion guidelines.13 The rate of appropriateness varies among studies. However, multiple studies have demonstrated an improvement in transfusion practices following targeted interventions, including educational initiatives, underscoring the requirement for implementing institutional interventions to enhance the appropriate use of FFP.13, 14, 19, 20

A recent multicenter study revealed that sub-therapeutic dosage accounted for 70.7% of 6088 plasma transfusions.9 Similarly, a multicenter study conducted in the United States revealed that the mean plasma transfusion dose was 3.1 ± 3.0 units, with sub-therapeutic dosage accounting for 61.6% of transfusions.21 A relatively lower rate of sub-therapeutic transfusions was observed in the present study, with 42.1% of all FFP transfusions classified as underdosed. Notably, this proportion increased to 50.2% when only inappropriate transfusions were considered.

FFP transfusion is considered ineffective in patients with mild INR elevation7; consequently, current guidelines advocate the restricted use of plasma transfusion in patients with minimally elevated INR.1-3, 5 However, a substantial proportion of FFP transfusions continue to be performed in cases with mildly elevated or normal INR levels. A multicenter study conducted by Khandelwal et al., with a mean pre-transfusion INR of 1.9 ± 1.6, reported that the pre-transfusion INR values were<1.5 and<1.8 in 44.0% and 66.4% of cases, respectively.9 Similarly, a nationwide study conducted in the UK revealed that 30.9% of FFP transfusions were performed at an INR of ≤1.5.22

The mean pre-transfusion INR was 1.81 ± 1.3 in the present study, with 56.3% and 68.3% of FFP transfusions performed at an INR of <1.5 and <1.7, respectively. These rates are relatively higher than those reported in previous studies. Notably, 94.8% of inappropriate FFP transfusions reported in the present study were performed in cases with a pre-transfusion INR of <1.7. The continued routine and/or empirical ordering of plasma products despite guideline updates may be the primary driver of these inappropriate transfusions. Thus, continuous monitoring and reinforcement of FFP transfusion guidelines must be enforced to optimise plasma utilisation and ensure more effective and evidence-based transfusion practices.

The classification algorithm used in the present study encompassed the most widely accepted indications for FFP transfusion.1-7, 18, 23 However, patients with conditions that required the correction of vitamin K deficiency or reversal of warfarin effects were excluded based on the South Korean National Transfusion Guidelines, which recommend FFP transfusion for the management of active bleeding or perioperative conditions.18 This classification primarily aims to provide a concise overview of FFP transfusion practices based on established indications. This may have resulted in more nuanced or less common clinical scenarios, which account for a smaller proportion of cases, being overlooked.

The proportion of inappropriate FFP transfusions in the emergency department of Hospital A was higher than that in Hospital B. Hospital A is a regional trauma center; thus, the patient population may differ in terms of severity and emergency situations, thereby necessitating the timely transfusion of plasma products, even in the absence of strictly defined criteria. The increased proportion of inappropriate FFP transfusions observed in the emergency medicine department and other trauma-related departments such as general surgery, neurosurgery, and cardiovascular thoracic surgery also reflects this trend. This finding highlights the substantial variation across institutions in terms of transfusion practices, emphasising the requirement for developing institution-specific management strategies. The variability in the rate of appropriateness reported in previous studies9-13 may be attributed to the differences in clinical settings, transfusion requirements, and the criteria used to define appropriate and inappropriate transfusions.

This study has certain limitations. First, the combined data may not be fully representative of broader transfusion practices, given the distinct characteristics of the two hospitals included in the analysis. Large-scale multicenter studies must be conducted to achieve a more comprehensive and generalised understanding of the appropriateness of FFP transfusion. Second, FFP transfusions were classified according to an algorithmic hierarchy wherein cases meeting multiple conditions were assigned to the first applicable category based on the algorithm. This approach may have led to an overlap between the severe bleeding and surgery/invasive procedure groups. However, the evaluation of appropriateness was conducted using established criteria; thus, further classification of inappropriate FFP transfusions addressed any overlap. Lastly, the criteria adopted herein may have led to the overestimation of the proportion of inappropriate FFP transfusions. Transfusions performed for the management of severe bleeding in the absence of elevated PT and/or aPTT values were deemed inappropriate. However, some of these transfusions may have been justified, as the absence of massive bleeding does not necessarily exclude the presence of clinically significant bleeding. Nevertheless, these patients were considered to not have a clinically relevant condition warranting FFP transfusion, as the laboratory results were within the normal range.

In conclusion, 40.6% of FFP transfusions performed in two tertiary hospitals were deemed inappropriate in the present study owing to failure to meet laboratory criteria. The variation between the rates of inappropriate transfusion in the two institutions highlights the requirement for developing tailored institution-specific management strategies to optimise FFP transfusion practices.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Hyun-Ji Lee, Jongmin Kim: conceptualization. Hyung-Hoi Kim, Hyun-Ji Lee: methodology. Jongmin Kim, Kae Lyang Koo: investigation. Hyun-Ji Lee, Jongmin Kim: visualisation. Hyung-Hoi Kim, Hyun-Ji Lee: funding acquisition. Hyung-Hoi Kim, Hyun-Ji Lee: project administration. Hyung-Hoi Kim, Hyun-Ji Lee: supervision. Jongmin Kim: writing – original draft. Hyun-Ji Lee, Jongmin Kim: writing – review & editing.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was supported by a 2024 research grant from Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no competing interests.

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

The institutional Review Boards of Pusan National University Hospital and Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital waived the need to obtain consent for the collection, analysis, and publication of retrospectively obtained and anonymized data for this non-interventional study.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.