Introduction to the Special Issue “The 2019 Swiss National Elections”

Abstract

enThis Special Issue brings together a large variety of contributions dealing with the influence of issues and issue competition, the structure of attitudes towards immigration and international cooperation and a series of non-policy factors such as campaign consultants and the rise of female representation in Switzerland. In this introduction we place the contributions in the broader framework of current debates in the international literature and stress the substantial and methodological innovations of the articles. Last, we offer some more general thoughts on almost 30 years of Swiss electoral research taking stock of the historical development.

Zusammenfassung

deDiese Sonderausgabe umfasst eine Vielzahl von Beiträgen, die sich mit dem Einfluss von Themen und Themenkonkurrenz, der Struktur von Einstellungen gegenüber Einwanderung und internationaler Zusammenarbeit sowie einer Reihe themenunabhängiger politischer Faktoren wie Wahlkampfberatern und dem Anstieg der Frauenquote in der Schweiz befassen. In dieser Einleitung ordnen wir die Beiträge in den breiteren Rahmen aktueller Debatten in der internationalen Literatur ein und betonen die inhaltlichen und methodischen Innovationen der Artikel. Schliesslich formulieren wir einige allgemeinere Überlegungen zu fast 30 Jahren Schweizer Wahlforschung und ziehen eine Bilanz der historischen Entwicklung.

Résumé

frCe numéro spécial rassemble une grande variété de contributions traitant de l'influence des enjeux et de la concurrence entre enjeux, de la structure des attitudes envers l'immigration et la coopération internationale et d'une série de facteurs non liés aux enjeux tels que les consultants de campagne et l'augmentation de la représentation féminine en Suisse. Dans cette introduction, nous plaçons les contributions dans le cadre plus large des débats actuels de la littérature internationale et soulignons les innovations substantielles et méthodologiques des articles. Enfin, nous proposons quelques réflexions plus générales sur près de 30 ans de recherche électorale en Suisse et faisons le point sur l'évolution historique.

This Special Issue “The 2019 Swiss National Elections” assembles eleven articles that offer new insights into the electoral behavior of Swiss citizens in the 2019 elections and beyond. Like the Special Issues on previous national elections (Giger et al., 2018; Lachat et al., 2014; Lutz, 2010), this volume includes contributions that approach the topic from a variety of angles and with different methods and data.

A first group of articles investigates the role of issue ownership and issue competence, from the perspective of the party supply side on the one hand, and from the voters' perspective on the other. The Swiss case – and the elections in 2019 – are particularly interesting when it comes to issue-driven political campaigns: first, because the issue of the environment was dominant (see as well Bernhard, 2020), and second, because in this very polarized party system, parties on the left are much closer to each other ideologically than in other European countries. A second group of articles contributes to one of the currently most salient questions in European politics: how to balance international cooperation and integration with concerns regarding immigration. The articles in this Special Issue shed light on voters' preferences about these topics and investigate if parties and voters align on these questions. Finally, a third group of articles addresses aspects of the electoral campaign and voting behavior that are not directly related to political issues, but rather to candidate characteristics and the specific context of voter mobilization in a digital world.

We see this variety of perspectives and entry points as an asset of Swiss electoral research that has contributed much to our knowledge of the decision-making process of Swiss citizens and the important role the context plays for their vote choice. As a matter of fact, we can now look back on almost 30 years of (modern) electoral research in Switzerland and on research covering seven elections since 1995. We saw this milestone as an opportunity to take stock of Swiss electoral research and provide some quantitative measures as well as a more qualitative assessment of the state of this sub-discipline in the last part of this introduction. In what follows, we provide some information about the main outcomes of the 2019 national elections before highlighting the substantive and methodological innovations of the contributions assembled in this volume. Last, we offer some more general thoughts on the state of Swiss electoral research in 2022.

MAIN OUTCOMES OF THE 2019 SWISS NATIONAL ELECTIONS1

Long known for its remarkable stability, the Swiss political landscape has experienced several important shifts since the mid-1990s: first, the spectacular rise of the Swiss People's Party (SVP) between 1995 and 2007, followed by the successful emergence of two new center parties (BDP and GLP) in the 2011 elections, and finally, a return of polarization between a stable left and a reinforced political right in the 2015 elections. In continuation of this new trend of relative instability – at least for Swiss standards – and in spite of the lowest turnout rate in twenty years (45.1%), the 2019 Swiss national elections have led to what can be qualified as historic changes in both the party system and women's political representation.

Regarding party system changes, the two green parties—the Greens (GPS) and the Green-Liberals—made spectacular gains in an election that was dominated by voters' concerns about climate change. When asked about the most important problem facing Switzerland, 26 per cent of the citizens surveyed in the national post-election study Selects mentioned environmental issues, which placed this issue on top of voters' problem perceptions (Tresch et al., 2020: 30). In this context, the Greens, helped by their reputation of issue-handling competence and commitment, managed to increase their vote share by 6.1 percentage points and reached 13.2 per cent of the votes (Table 1). This result was unprecedented in two respects: on the one hand, for the first time in its party history, the GPS passed the 10 per cent hurdle and outperformed the Christian-Democrats (CVP), thus becoming the fourth largest party in Switzerland. On the other hand, their score allowed the Greens to win 17 seats in the National Council—the largest seat gain of a party since the introduction of proportional representation in 1918 (two more than the SVP's previous record gain in 1999). Although other smaller parties lost some of their voters, most notably the conservative BDP (which subsequently merged with the CVP in 2021 to form “The Center”), together the non-governmental parties have never held a share of voters (31.1%) as high as in the 2019 elections. Conversely, the four governing parties suffered their worst election result since 1918 and reached only 68.9 per cent of the votes. Among the four governing parties, the national-conservative SVP suffered the largest losses: its vote share decreased by 3.8 percentage points and it lost 12 seats in the National Council, which represents the largest seat loss of a party since 1918. In spite of these losses, the SVP clearly remained the strongest party in Switzerland. The other three governing parties, the Social-Democrats (SP), the CVP and the Liberals (FDP), all recorded all-time low vote shares and lost each several seats in the lower house.

| National Council | Council of States | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes (%) | Difference 2015/2019 | Seats (N) | Difference 2015/2019 | Seats (N) | Difference 2015/2019 | |

| Governing parties | 68.9 | −7.4 | 146 | −22 | 41 | −3 |

| SVP | 25.6 | −3.8 | 53 | −12 | 7 | +1 |

| SPS | 16.8 | −2.0 | 39 | −4 | 9 | −3 |

| FDP | 15.1 | −1.3 | 29 | −4 | 12 | −1 |

| CVP | 11.4 | −0.3 | 25 | −2 | 13 | 0 |

| Non-governing parties | 31.1 | +7.4 | 54 | +22 | 5 | +3 |

| GPS | 13.2 | +6.1 | 28 | +17 | 5 | +4 |

| GLP | 7.8 | +3.2 | 16 | +9 | 0 | 0 |

| Others | 10.1 | −2.0 | 10 | −4 | 0 | −1 |

- Source: Federal Statistical Office.

- Italic values indicate governing parties and non-governing parties.

Altogether, and in spite of the important vote transfers from the SP to the GPS (see Petitpas & Sciarini, 2022, in this volume), the 2019 elections to the National Council resulted in a reinforcement of the political left: in terms of vote shares and seats, the SP, the GPS, and the smaller parties of the radical left increased their joint representation. This results stands in stark contrast to the 2015 elections, which saw the National Council shift markedly to the right. Yet, whereas the 2015 elections resulted in different political majorities in the two chambers of the Swiss parliament (a majority of the right in the National Council, and a center-left majority in the Council of States) (Giger et al., 2018), the configuration of power between the political camps is now more similar in both chambers. As a matter of fact, the political left gained one seat in the Council of States (Greens +4 seats, SP -3 seats), the CVP was able to hold its 13 seats, and while on the right the FDP lost one mandate, the SVP gained a seat.

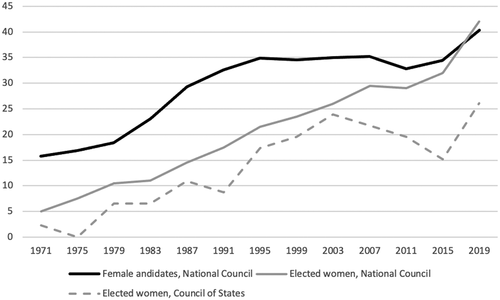

The 2019 elections were also historic for women's political representation, regarding the numbers of both female candidates and women elected to parliament. Figure 1 shows that the share of female candidates running for a mandate in the National Council sharply increased in the 2019 elections and passed the 40 percent threshold for the first time. Female candidates were even in the majority on the electoral lists of the SP and the Greens. Similarly, the share of women elected to the National Council and the Council of States reached an all-time high. In the National Council, the share of women among those elected increased almost linearly between 1971–2003, then slowed down somewhat, before it surpassed 30 percent in the 2015 elections. In 2019, it jumped by 10 percent to reach a historic 42 percent, a score that places Switzerland well above the European average and close to the Nordic countries in terms of female representation in parliament. Among the newly elected, women even formed a majority (53%) in the National Council in 2019. Importantly, for the first time since the introduction of women's suffrage in 1971, the proportion of women elected to the National Council was slightly higher than the proportion of female candidates, which is indicative of voters' increased willingness to elect women.

Source: Federal Statistical Office.

In the Council of States, the 2019 elections marked a turning point: after a steady decline of women's representation between 2003 and 2015, the proportion of women rose by 10.9 percentage points to 26.1 per cent in 2019. This surge in women's representation in both chambers of the Swiss parliament has to be seen against the backdrop of both the national “Women's strike” on 14 June 2019, when hundreds of thousands of women across Switzerland took the streets to call for gender equality, as well as the countrywide feminist campaign “Helvetia calling”, which was launched by the women's organization “alliance F" and the political movement “Operation Libero” with the aim of achieving gender parity in parliament. The campaign's goal was to motivate women to run for office and to urge parties to nominate women and place them on promising list positions. The contribution by Giger et al. (2022) in this volume sheds light on the role of such supply-side factors in explaining the success of women in the 2019 election.

Despite the surge of the Greens and women in the parliamentary elections, the composition of the executive has remained unchanged and all incumbent members of the Federal Council have been re-elected on December 11, 2019 (for more details, see Bernhard, 2020: 1346–7). In a legislative term dominated by the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020, the environmental parties have had a hard time pushing through their agenda. When the tightening of the CO2-Act was rejected in a popular vote in June 2020, this meant a major setback for environmental-friendly parties. The “green wave” has been unbroken on the cantonal level, however, where the Greens and the Green-Liberals have been the winners of most of the 16 parliamentary elections that have been held since the 2019 federal elections (see also Seitz, 2022).

THEMATIC CONTRIBUTIONS OF THIS SPECIAL ISSUE TO THE STUDY OF ELECTIONS

The contributions of this Special Issue all make use of data collected within the Swiss election study “Selects” that started in 1995 with the goal to collect high-quality data on voting behavior and turnout at Swiss national elections.2 The 2019 edition of Selects had four components: a post-election survey (1) and a panel survey (2) among voters, a candidate survey (3), as well as a (social) media analysis (4). While most contributions in this Special Issue use data from one of these four components, some link data from several components or combine Selects data with external data sources, such as party manifestos, campaign ads or official statistics.

Thematically, the contributions of this Special Issue highlight some of the specific developments of the 2019 elections just described above but also contribute to a number of topics in the international literature. We distinguish between three main thematic clusters. A first set of papers deals with the role of issues, focusing especially on issue ownership and issue competence from the perspectives of both the parties and voters. A second group of papers zooms in on one particular issue: the broad question on how to balance international cooperation and integration with concerns about immigration. A third cluster of manuscripts investigates aspects of the electoral campaign and voting behavior that are not directly related to political issues.

The 2019 elections were particular insofar as the campaign took place in a context with two dominating events: the women's strike that took place in June 2019, and the ongoing climate change movement that was setting the agenda externally. The environmental issue is taken up by a first set of papers. The contribution by Lüth and Schaffer (2022) examines environmental and energy policy over two decades by combining data from party manifestos with voter preferences as measured in the Selects post-election surveys between 2007–2019. The authors find that issues related to climate change are now more polarized than they used to be, which shows that environmental issues can no longer be simply treated as valence issues but structure the political space like other positional issues. Another important finding from this study is that the traditional issue owning Green parties focus less on environmental issues (in relative terms), while parties to the right of the political spectrum followed the shift in public priorities and have considerably increased the salience of environmental issues over the last decades. Gilardi, Gessler, Kubli and Müller (2022) also address questions of issue competition, but specifically focus on the campaign dynamics of 2019. Relying on tweets and press releases of the major Swiss parties between January and October 2019, and newspaper articles from the same time period, they examine the link between the parties' issue ownership and their agenda-setting capacity. Their methodological approach combines a machine-learning classifier to determine the issue focus of the documents with vector autoregression models to determine which parties were able to lead the agenda on specific issues (environment, gender, Europe and immigration). Interestingly, the gender issue received only little attention in the traditional media and social media discussions overall, with the exception of a short time period around the June 14th women's strike (Gilardi et al., 2022). Another important finding from this study is that party and media agendas were only weakly related. The authors conclude that in contexts where the agenda of the campaign is set exogenously by national and international events, even parties that own an issue can hardly influence the agenda. The contribution by Borgeat (2022) asks a similar question, namely whether parties have an incentive to emphasize their issues or rather “ride the wave” (Ansolabehere & Iyengar, 1994) of currently salient issues in order to gain votes beyond their core constituency. Combining the Selects panel survey with newspaper ads coded by “Année Politique Suisse”, Borgeat (2022) shows that parties try to win potential voters by adapting their issue emphasis, a result that speaks to the theory of broad-appeal strategies (Somer-Topcu, 2015).

When looking at citizen's voting behavior, it is important to understand how the perception of different parties' issue competences influences vote choices. Petitpas and Sciarini (2022) contribute to research that conceptualizes the vote decision as a two-step process consisting of a consideration and a choice stage (e.g. Oscarsson & Rosema, 2019). They expect that in the choice stage issue competence rather than ideological positions become important for the vote choice between the Social Democrats and the Greens. This view is especially fruitful when parties are ideologically close and people need additional information to make their choice. Relying on propensity to vote scales (PTVs), their study however shows that even in the choice stage, ideological considerations are still important, although voters who shifted their competence attribution on the environment during the campaign were more likely to vote for the Green party. Finally, the study by Marquis and Tresch (2022) confirms the role of competence attribution in vote choice. The authors argue that voters' issue ownership perceptions of different parties are most likely to influence their vote choice when the issue is salient and ownership attributions are easily accessible in their minds. Measuring the accessibility of issue competence perceptions on five issues by response latency, they demonstrate that the accessibility of competence attributions indeed matters for the vote choice. They also highlight that issue competence attribution towards parties that own an issue that is important for a large part of the electorate – such as the Green party and the environment – plays an important part in this process.

A second group of papers in this Special Issue addresses two other issue areas that have been decisive in earlier campaigns and continue to structure the political conflict in Switzerland: immigration and international integration. Lauener, Emmenegger, Häusermann and Walter (2022) investigate two specific groups of cross-pressured voters: On the left, they argue, voters are generally open to further European integration but worry about the downgrading of labor protection standards that might come as a consequence of the free movement of persons. On the right, voters are cross-pressured because they support financial and economic integration but are more skeptical about the cultural consequences of immigration. The authors look at both tensions and examine the potential choices cross-pressured voters would make. They find that a majority in the general electorate would choose integration over immigration control; among the voters (those who support a specific party) however, there seems to be a substantial group that prefers social protection over integration. These results point to potential resistance to further economic integration that might considerably influence the future of Swiss-EU relations and in particular the negotiations of the Institutional Framework Agreement. With a similar focus, the contribution by Lauener (2022) looks more closely into the comparative positions of voters and candidates in the realm of EU relations. Combining the panel survey (voters) with the candidate survey (elites) his study shows how both align on four integration issues. The author finds good congruence between candidates and voters overall, but this result comes with two nuances. First, politicians in general – except those from the SVP – seem to take a more pro-EU position than their voters. Second, among the left (GPS and SP), the elite's supports for maintaining the social protection measures over adopting the Institutional Framework Agreement is stronger than that of their voters. A last contribution in this group of manuscripts speaks to the consequences of immigration by comparing the political preferences of non-native and native Swiss voters. Earlier research has found different voting patterns, concluding that voters with migration background tend to vote for left-of-center parties (e.g. Strijbis, 2014). Camatarri, Favero, Gallina and Luartz (2022) make an important refinement: combining the post-election studies of 2015 and 2019, they focus less on the vote itself than on the reasons for a specific vote choice. Their analyses show that for non-native voters key issues that were central in the campaign are less important than for native voters, but with relevant differences across migration backgrounds: While positions on the environment were closely connected to vote choice among second generation Swiss and migrants from (Western) European countries, policy issues in general seem to be detached from the vote choice among other migrants from outside Europe.

In sum, the first and second group of contributions highlight the importance of issue salience and issue ownership – in particular of environmental and climate issues in the 2019 elections. A third group of papers focuses on other, non-policy related factors in the campaign. The contribution by Nai, Tresch and Maier (2022) examines the role of campaign consultants. Consultants are becoming more important in the context of increasingly professionalized campaigns. Using data from the candidate survey, the authors show that consultants specifically tailor their strategic advice to the candidate's personality profile. Accordingly, their results show that negative campaigning is a function of the candidates' personality: those with lower scores on agreeableness and conscientiousness are more likely to engage in negative campaigning. The authors emphasize the important role of campaign consultants. However, they find no evidence for a positive effect of the tailored campaigns on electoral success. The contribution by Giger, Traber, Gilardi and Bütikofer (2022) studies the role of another aspect of a candidate's profile, namely, gender. While gender issues were surprisingly underrepresented in the media and parties campaigns (Gilardi et al., 2022), the success of female candidates was surely one of the most remarkable aspects of the 2019 elections. Giger et al. (2022) investigate the mechanisms that lead to this surge of women's representation. They show that the share of female candidates increased considerably compared to previous elections, and that women held better positions on party lists. The authors emphasize the important relationship between the share of women on the lists and their electoral success. Further, another factor that contributed to the better representation of women was the success of Green parties, since the latter included more female candidates on their lists. But the authors also find evidence for an attitudinal change among the voters, who became more supportive of female candidates overall.

A final important aspect of the campaign is how voters get informed about candidates, how they seek information, and which kind of information about the campaigns they see. Ackermann and Stadelmann-Steffen (2022) compare two groups of voters: those who mostly use social media and online platforms, and those who seek information offline. They use a new measurement of online political activities in the Selects panel survey to test two competing arguments: political online activists might either receive more personalized and pre-selected information and therefore become more constrained ideologically (echo chamber argument), or they may, to the contrary, be more open-minded as the internet offers broader information than offline sources, and voters that are active online might also be exposed to counter-attitudinal information (deliberation argument). Using vote-splitting as a behavioral indicator for political open-mindedness, the authors find no general effect of online activities. Only voters with low political interest seem to be less open minded – and less likely to split their vote – when seeking information online.

TAKING STOCK AFTER 25 YEARS: THE EVOLUTION OF ELECTORAL RESEARCH IN SWITZERLAND

Modern electoral behavior research (re-)started in Switzerland with the 1995 Swiss National Elections (see Farago, 1995) when a new infrastructure for studying Swiss national elections was introduced. Ever since the Swiss election study Selects has collected data on the electoral behavior of Swiss citizens and has subsequently expanded not only the sample size but also the type of data collected (see also Kritzinger, 2018).

Seven national elections and nearly 30 years later, it is time to take stock of the evolution of electoral research in Switzerland. Since the resurrection of electoral research with the 1995 elections, we have seen an enormous development in this subdiscipline of political science research. Not only have two books and by now five Special Issues in the Swiss Political Science Review (SPSR) been published, but the team and scope of the Swiss election study has also been massively expanded. For now, in addition to a post-electoral survey, Selects includes a campaign panel survey, a candidate survey and media analyses. It thus allows to put citizens' voting behavior in the context of the campaign information environment and offers an encompassing picture of election campaigns and outcomes.

This resulted in a considerable research output. A quick search in the SPSR reveals that 69 research articles have been published on Swiss electoral behavior, with 50 in the Special Issues and 19 in other volumes.3 The majority of these publications are assembled in the Special Issues on the respective elections, which showcases the importance of this concerted action for the study of electoral research in Switzerland. Thanks to the effort by the scientific community, every four years about 10 articles are published on various aspects of Swiss electoral behavior, thus furthering our knowledge of how (Swiss) voters decide, but also making it possible to connect findings on Switzerland to the larger scientific debates and general international trends.

In our view the instrument of the Special Issue coupled with the voluntary engagement of the Guest Editors is especially needed, given the fact that no professorship or faculty position is dedicated to electoral behavior in Switzerland as such. It thus remains in the realm of individual action and single scholars interested in elections to do research on the topic. And indeed, looking at the research output, the advancements in the literature are very much driven by prominent figures such as Pascal Sciarini who contributed to one of the two books and all five Special Issues that have been published since the start of Selects. The high productivity of key players, their ability to raise research funds, as well as the small size of the research community in Switzerland are in our view responsible for this concentration of research output on a few prominent scholars. At the same time, the Special Issues on the national elections have always offered an opportunity for junior scholars to feature their work (see e.g., Borgeat, 2022, and Lauener, 2022, in this volume).

In sum, the topics covered in Swiss electoral research are very diverse. We find studies on the multi-level nature of elections in Switzerland (Selb, 2006), alongside with works looking at the ideological spaces of candidates and citizens (Leimgruber et al., 2010), or the multidimensional ideological space of citizens alone (Kurella & Rosset, 2018). Scholars have looked at the long-term dynamics of electoral behavior in Switzerland (Rennwald, 2014) and at more short-term developments (e.g. Kriesi & Sciarini, 2003; Petitpas & Sciarini, 2018; Pianzola, 2014) or more idiosyncratic elements of the elections under study (e.g. Giger et al., 2022; Marquis, 2010).

All in all, we note that despite the small community working on the topic, electoral research in Switzerland flourishes and steadily produces new important insights into how Swiss citizens behave at the ballot booth and what drives their choices. Importantly, Swiss scholars do not work in isolation but have taken up important debates – substantively but also methodologically – and examined them for the Swiss case, sometimes adopting a comparative perspective (e.g., Kitschelt & McGann, 2003). In the latest Special Issue, we see for example new work including survey response times as unobtrusive measure of attitude accessibility (Marquis & Tresch, 2022) or studies looking at social media (Ackermann & Stadelmann-Steffen, 2022). Also, the community has taken up trends, such as examining populism and populist attitudes (see e.g. Bernhard & Hänggli, 2018; Fontana et al., 2006; Storz & Bernauer, 2018) or the dynamics of the issue competition with an emphasis on issue ownership (Lachat, 2014; Petitpas & Sciarini, 2018, 2022). Also, we note a trend towards more multi-method and multi-data work, for instance in recent studies by Gilardi et al. (2022) or Borgeat (2022).

In addition to these more academic, often English-written, contributions published in the SPSR, there have been several efforts to make research findings accessible to a broader audience, including the media, political parties, and citizens. For instance, several edited volumes present important results in a methodologically less complex but generally more understandable format and in a national language (e.g., Freitag & Vatter, 2015; Kriesi et al., 2005; Nicolet & Sciarini, 2009). The same is true of a brochure, published by the Selects team at FORS after each national election since 2007 and presented to the media and the public at a national press conference (see Tresch et al., 2020, for the latest example). In the same vein, many authors participating in the Special Issues on national elections have presented summaries of their findings on the political blog DeFacto, which is followed by many journalists.

Nonetheless, we believe that electoral research in Switzerland remains somewhat fragile. Its success and proliferation very much depends on motivated individuals. Without their valuable engagement and research input, we would not know much about the decision-making criteria of Swiss citizens and even now, certain aspects of electoral behavior remain a black-box. For example, we only have very few publications looking at electoral participation in Switzerland as a whole with the last paper published in a Special Issue in 2014 (Stadelmann-Steffen & Koller, 2014). Also, compared to the number of studies based on data from the various voter surveys, fewer work has used the candidate survey, which has been included into Selects since 2007 as part of a large international cooperative project, the Comparative Candidate Survey (CCS). Another dataset that is less used is the media data, in particular the news content. Without it, important questions in political communication regarding the input of political information and its effects remain unanswered.

It is thus vital for the future of electoral research in Switzerland to not only gather high-quality data as the Selects team in Lausanne has been doing for years now but also to make it known among interested scholars in Switzerland and beyond. This is mainly achieved through the participation in two important international networks – the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES) regarding voter behavior and the Comparative Candidate Survey (CCS) regarding candidate behavior. The open call for modules and questions to be included in Selects is another means to ensure that the scientific community is on board and uses the data actively. The newly available 4-year panel data that allows to combine the study of direct democratic and electoral behavior of Swiss citizens hopefully also stimulates new research in this area.4 The availability of new data and innovative research designs may also help ensure that Selects remains as attractive a project for young academics as it has been up to now and contributes to the promotion of the next generation of electoral researchers. Indeed, many PhD theses have been written based on Selects data (for recent examples, see e.g., De Rocchi, 2018; Goldberg, 2017).

To conclude, a lot has been said about Swiss electoral behavior but still important gaps remain and new questions emerge. We think for example of the further impact of changes in the information environment with more and more online news consumption or the rapidly changing issue salience that affects citizens in their choices. We thus look forward to reading new exciting work on Swiss electoral behavior in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank several persons who contributed to this Special Issue at various stages of the preparation. First, we appreciate the very helpful and constructive comments by the panel discussants at the online workshop held in January 2021, Alexandra Feddersen, Alessandro Nai, Julia Partheymüller, Oliver Strijbis, and Markus Wagner. Second, we highly value the smooth and efficient collaboration with the editorial office of the Swiss Political Science Review, Martino Maggetti and Iris Meyer in particular. Our thanks also go to the anonymous reviewers of the Special Issue who did a tremendous job in making the contributions even better. Last but not least, we would like to thank the Selects team at FORS for the preparation and online publication of the data - without them this Special Issue would not be possible. Open access funding provided by Universite de Geneve.

Biographies

Nathalie Giger works as Associate Professor of Political Behavior at the University of Geneva. She studies political behavior and attitude formation in comparative perspective, with a focus on inequality and digitalization. [email protected]

is an assistant professor of Political Sociology at the University of Basel, Switzerland. Her research focuses on party competition, political representation, and political behavior. [email protected]

Anke Tresch is Head of the Political Surveys team at FORS and an Associate Professor (ad personam) in Political Sociology at the University of Lausanne. Her research focuses on electoral behavior and campaigns, party competition, and political communication.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1 For other accounts of the 2019 elections, see Bernhard (2020) or Tresch et al. (2020).

- 2 For more information, see www.selects.ch. All collected data are publicly available to interested researchers and can be accessed after registration on the online platform SWISSUbase (https://www.swissubase.ch/).

- 3 We searched the SPSR for key terms such as “election/electoral” and voters/voting” and subsequently assessed based on the abstract whether this article indeed deals with electoral behavior in Switzerland. The full list of articles is available on request. It must be noted that many articles are also published in international journals and are not considered here.

- 4 See Selects 2019 Panel Survey (waves 1–5), available on SWISSUbase, https://doi.org/10.48573/g1em-fa05.