The Effect of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Inequality

Any opinions and conclusions are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Peter Meyer, Harley Frazis, and Leo Sveikauskas are Research Economists at the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Michael Schultz is an Economist at the BLS. Joe Piacentini recently retired as Economic Advisor to the Commissioner of the BLS. The authors appreciate helpful comments from colleagues including Cindy Cunningham, Thesia I. Garner, Elizabeth Handwerker, Mark Loewenstein, Sabrina Pabilonia, Anne Polivka, Jay Stewart, outside reviewer Shelley Phipps, and the CDC Health Economics Research Group.

Abstract

This paper reviews the economic literature on how the COVID-19 pandemic and responses to it affected income inequality throughout the world. Inequality had been rising long before the pandemic. The COVID shock affected employment, income, and education differently for various occupations and population groups. The pandemic initially disrupted lower-paid, service-sector employment, particularly affecting women and lower-income groups. Government policies in response to the pandemic mitigated income losses. School and day-care closures disrupted the work of parents, especially mothers. These effects have generally ended. Lasting changes in work patterns, consumer demand, and production will tend to benefit higher-income groups and to erode opportunities for some less advantaged workers, increasing income inequality over the long run. Opportunities for remote work, especially for highly paid workers, have increased permanently. School disruptions have particularly affected lower-income students, which will tend to increase inequality among future workers.

1 Introduction

This review examines the economic literature addressing the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, and related policy responses, on current and future income inequality. Several previous survey articles have considered the impact that COVID-19 has had on employment, earnings, and inequality. We draw from Stantcheva's (2022) study of the impact on the world, Miguel and Mobarak's (2022) study of developing countries, Blundell et al.'s (2022) detailed study of the United Kingdom, and Piacentini et al.'s review (Piacentini et al., 2022) for the United States. We synthesize insights from these prior summaries, especially the detailed literature on the United States, and update these studies by including publications since mid-2022. Because the effects of COVID often differed between wealthier and poorer countries, some portions of this review include subsections about the developing world.

The COVID shock occurred in a context in which, over the last 40 years, income inequality has increased in many countries. New technologies, increased international trade, and the growth of “superstar” firms all tended to provide relatively greater opportunities for more educated, higher-earning individuals. Autor (2010) succinctly summarized the main forces in the U.S.: “the key contributors to the polarization of jobs are the automatization of routine tasks and, to a smaller extent, the internationalization of labor markets through trade, and, more recently, offshoring.” The erosion of middle-income jobs “shunted non-college workers from middle-skill career occupations that reward specialized and differentiated skills into traditionally low-education occupations that demand primarily generic skills.” These trends affected non-college workers “in middle skill blue-collar production and white-collar office, administrative, and clerical jobs” (Autor, 2019). Goos and Manning (2007) and Goos et al. (2014) wrote pioneering studies on these topics using data for the United Kingdom.1

The discussion below reviews both short-run and long-run effects of the pandemic on inequality. The pandemic disrupted lower-paid, service sector employment the most, disadvantaging women and lower income groups. This threatened to widen inequality, but economic policies implemented in response to the pandemic often more than offset the impact of these disruptions. In the longer run, the pandemic seems likely to widen inequality, mainly because higher-paid workers reap more advantages from remote work, and school closures disproportionately affected less-advantaged students. We also discuss other forces affecting long-run inequality in both developed and developing economies.

2 New data and measurement

Estimates of inequality vary depending on the concepts, methods, and data used to measure it. Several international institutions offer standard measures of income inequality for many countries. These include the World Bank's Poverty and Inequality Platform of the, which collects information on inequality from national statistical agencies, and the World Inequality Database. The latter data include comprehensive measures of income from capital, which many other sources cannot fully cover. An additional challenge was that the pandemic disrupted household surveys in many countries (Mahler et al., 2022).

Methods of measuring the distributions of income, consumption, and wealth in developed countries have improved substantially in recent years and are being integrated into official statistics and international comparisons. Piketty et al. (2018) developed a version of Distributional National Accounts (DINA), which distributes national income to its earners. Auten and Splinter (forthcoming) construct income measures from detailed U.S. tax information and find inequality grows more slowly than Piketty et al. (2018) report.2

Ederer et al. (2022) compare DINA measures with the household surveys that national income accountants typically use to describe inequality. Ederer et al. (2022, p. 668) remark that the DINA and household income measures both “often lack information on the composition of incomes and the contribution of different income sources to the distribution or to the joint distribution of income with policy-relevant socioeconomic characteristics at the household level.” Blanchet et al. (BSZ) (2022) introduce novel methods that enable them to assign each component of U.S. income to subgroups of people with specific socioeconomic characteristics. They measure income from publicly available sources and include capital income and transfer payments. These methods allow to report, for example, what share of Black incomes comes from capital or to trace the earnings of women and Blacks consistently over the pandemic years. An advantage of BSZ's approach is that their estimates are available in real time. Because of these advantages, we often cite evidence from BSZ.

Government agencies continue to develop further measures of distributional national accounts. Fixler et al. (2017) developed measures of inequality from the U.S. national accounts. Balestra and Oehler (2023) developed OECD experimental measures of how national income is distributed to different demographic groups. An OECD Handbook (2024) recommends methods of preparing distributional national accounts.

National and international institutions are increasingly preparing measures of income distributions, sometimes integrated with distributional accounts of consumption and wealth. OECD, Eurostat, and national governments have made commitments to this kind of research and accounting. The problem is complex because each country has a different set of data available.

For the pandemic period in particular, useful studies of the distribution of income in developed countries include Stantcheva (2022, Table 1), Bruckmeier et al. (2021) and Immel et al. (2022) on Germany, Markevičiūtė et al. (2022) on Lithuania, Statistics Canada (2022) on Canada, and Angelov and Waldenström (2023) on Sweden. Private sector data on financial transactions also allowed studies of the distribution of consumption expenditures, such as Cox et al. (2020) for the U.S., and Bounie et al. (2023) for France. For the U.S., Chetty et al. (2024) obtained information from credit cards, payroll processors, job posting firms, and banks to measure consumption and employment. Rapidly deployed government surveys, such as the U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey and Small Business Pulse Survey, also contribute to our understanding of the pandemic's effect.

3 Short run effects of COVID-19 and government responses

While all countries were affected by the pandemic, infection and mortality rates varied greatly by country. Initially, infection rates were greater in many of the rich countries than in poorer ones. The pandemic affected service occupations and work by women more than other kinds of work. Prices rose for staples and declined for travel and leisure services. Rapid government intervention narrowed inequality in many developed countries. As richer countries recovered economically, poorer nations suffered more.

Stantcheva (2022) reviews cross-national and nation-specific studies that clarify the pandemic's effects on income inequality in the developed world. As GDP fell, many countries implemented policies that supported family incomes. Income inequality consequently narrowed. She notes that, absent such policies, the pandemic would have widened inequality because less-advantaged groups generally suffered more job displacement and had fewer opportunities to shift to remote work.

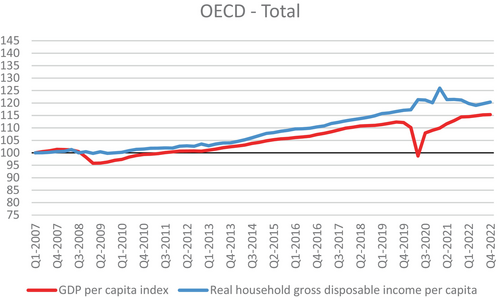

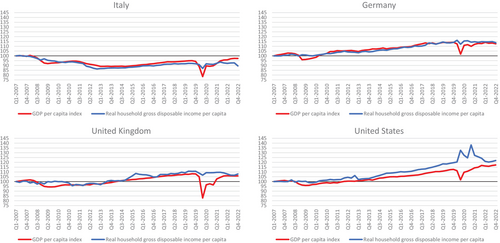

Figures 1 and 2 summarize short run GDP effects and government fiscal responses in OECD countries (as in Stantcheva, 2022). The sharp decline in GDP per capita brought OECD countries down to 2010 levels, on average. GDP in these countries had approximately recovered by the beginning of 2022. The fiscal response to the COVID emergency varied across countries. The U.S. made greater payouts to households and firms than most other countries, to such an extent that household income actually increased. Other governments provided wage subsidies or mandated that employers maintain employment. These responses to COVID caused differences in government debt. From 2019 to 2020, government debt as a proportion of GDP increased about 25 percentage points in the U.S., but only about 7 percentage points in Germany.3

Source: OECD Household dashboard database. Levels in the first quarter of 2007 are normalized to 100.

By May 2020, job retention programs supported ~50 million jobs in the OECD, about 10 times as many as during the 2007–2009 recession.4 Many countries subsidized job retention through established or new “short-time work” programs that replaced lost earnings. Such programs were widely used in Europe. In May 2020, short-time work programs supported 19 percent of German and 33 percent of French workers, but virtually no U.S. workers. Some countries subsidized job retention through wage subsidy programs, which share the cost of hours worked with employers, rather than paying for hours not worked. The U.S. temporarily enhanced unemployment benefits for many lower-paid workers. Overall, wage replacement rates tended to be greater in countries with job retention programs than in those that increased unemployment insurance payouts and tended to be higher for lower-wage workers.

3.1 Incomes, consumer spending, and poverty

Different data sources provide information on different aspects of the distribution of household income, spending, and consumption throughout the pandemic. BSZ produce comprehensive estimates of the distribution of U.S. incomes over these years. Leaving out transfers, the incomes of the highest and lowest income groups declined most sharply in 2020. These same groups recovered most strongly in 2021. The top 10 percent recovered their pre-pandemic income within 12 months, and lower-income groups recovered within 21 months. BSZ find that labor earnings for the bottom half of the distribution increased more rapidly than for the upper quartiles between January 2019 and September 2022.

Government transfers had a substantial equalizing effect during the pandemic. BSZ report that “after accounting for taxes and … transfers, average disposable income for the bottom 50% was nearly 20% higher in 2021 than 2019.” Kollar (2023) examines pre-tax and post-tax U.S. household income inequality using data from the Current Population Survey. In this data, the Gini index for pre-tax income increased steadily since 2007, and the 2020 and 2021 increases were similar to this trend. Post-tax income in the pandemic period includes transfer payments made through the tax system, such as the Economic Impact Payments and the Expanded Child Tax Credit. These transfer programs generally expired in 2022, so that, although pre-tax inequality declined modestly in 2022, post-tax inequality increased considerably in that year.

Government responses similarly reduced inequality effects in Europe. Clark et al. (2021) showed that inequality initially increased in France, Germany, Italy, and Spain, then fell due to government intervention. Menta (2022) examined related data on poverty. These studies find that, in these European countries, inequality and poverty peaked around May 2020.

Consumer spending fell more for higher income groups at the start of the pandemic. However, the savings balances of households lower in the income distribution did not decrease on average. Using credit- and debit-card data, Chetty et al. (2024) find that households in top-quartile income areas spent 34 percent less in mid-April 2020 than in March, whereas households in bottom-quartile areas spent only 23 percent less. Using Chase checking account and credit- and debit-card data, Cox et al. (2020) find that in March 2020 the pandemic brought about a large spending decline throughout the income distribution. Later in the pandemic, spending by low-income households recovered more quickly than high-income expenditures.

Using U.S. Consumer Expenditures Survey data, Meyer et al. (2022) find similar results for the entirety of 2020; consumption declined only for higher income households, partly because of reductions in travel and entertainment spending. These authors attribute income gains for lower-percentile households to government policy choices which averted a decline in their consumption expenditures. These payments were predominantly saved, or used to pay off debt, rather than spent (Armantier et al., 2021). Lower-income households spent somewhat more and paid down debt more in the short run, relative to higher-income households, according to a variety of data sources and researchers (Coibion et al., 2020; Parker et al., 2021). Garner et al. (2024) show that high-income consumers spent more on expensive travel and restaurants, so the decline in these industries reduced consumption inequality in 2020, then it returned to its previous level. Tauber and Van Zandweghe (2021) show that the 2020–2021 increase in durable goods expenditures reflected both a shift in consumer demand away from services and increased disposable income due to short term government transfers.

The same basic pattern holds true for countries outside the United States. Hacıoğlu-Hoke et al. (2021), using transaction data from the UK, show that in the early stages of the pandemic higher-income people reduced their consumption expenditures the most, and labor earnings fell most for low-income people. Government transfers played an important role in moderating the decline in earnings. Similarly, Bounie et al. (2023) show that in France, in the first wave of the pandemic, spending fell more for high-expenditure households. Low-expenditure households showed an increase in debt.

Because the data for many studies of consumer spending come from banks or credit-card providers, they exclude the poorest of the poor and therefore miss some material hardship such as food insecurity. Meyer et al. (2022) review the literature and find conflicting results. Bitler et al. (2020) compared estimates from the pre-Covid National Health Interview Survey with the Covid Impact Survey and found food insecurity was almost three times greater than pre-COVID rates in June 2020. Karpman and Zuckerman (2021) found from an Urban Institute survey that between December 2019 and December 2020, the share of U.S. adults reporting household food insecurity in the past 12 months declined from 23.9 percent to 20.5 percent. The two data sources are not directly comparable in content or timing, but the combination suggests that the government response to COVID reduced hunger by December 2020.

3.2 Effects of the pandemic period on specific groups

Industry and establishment characteristics

As the pandemic began, output declined sharply in retail trade, travel, and hospitality. Elective services declined in hospitals. Pandemic-related shifts in demand and policy changes reduced employment. Smaller firms suffered relatively greater employment losses than other U.S. employers early in the pandemic but recovered most of these losses within a year (Dalton et al., 2020; Dalton et al., 2021). Using Homebase payroll data, Dam et al. (2021) found that in the hard-hit retail, leisure, and hospitality industries, 35 percent of small businesses were still closed in May 2021, and their employment had fallen 25 percent during the pandemic. Dam et al. estimated that the original employers would rehire only about 4 percent of these displaced workers.

Chetty et al. (2024) examined the decline in U.S. consumer credit and debit card spending in the months just after the pandemic began. They found that two-thirds of the mid-April 2020 reduction in expenditures came from lower spending on goods or services that require in-person contact, such as hotels, transportation, and food services—even though these categories normally account for just one-third of spending. By July 2020, spending on tangible goods increased above pre-pandemic levels and increased labor demand in industries that manufacture, warehouse, or ship goods. Demand for in-person services remained depressed.

Occupation and education level

Many workers in high-contact jobs were furloughed immediately. The effect of the pandemic on worker incomes depended substantially on whether workers in particular industries or occupations could readily switch to at-home work. Malkov (2020) shows that occupations suitable for telework require more education and experience and greater cognitive, social, and computer skills. Such occupations also pay more. Occupations with higher mean wages had lower declines in employment during the pandemic (Cortes & Forsythe, 2023; Hershbein & Holzer, 2021). A reduction in travel, restaurants, and in-person leisure activities shifted labor demand towards greater reliance on cognitive requirements and post-secondary education and reduced the need for many physical skills (Ice et al., 2021; Shutters, 2021).

Thus, the pandemic recession hit the less-educated harder than other recessions, especially at the start. Employment recovery was also slower for the less educated because sectors such as leisure/hospitality and personal services that employ them intensively continued to be hard-hit (Hershbein & Holzer, 2021; Groshen & Holzer, 2023). High school graduates experienced the greatest initial decline in employment rates while those with post-graduate education experienced the least. Even after controlling for major occupation, major industry, and demographic variables, employment losses in April 2020 varied by several percentage points across education levels. The difference between these groups declined by 2021 (Lee et al., 2021).

Women

Reviewing the evidence for many developed countries, Stantcheva (2022) finds that women generally suffered more work disruption than men, because they were more concentrated in adversely affected jobs, and because they took on greater childcare responsibilities when schools and daycare facilities closed.

In the U.S., declines in women's employment and labor force participation during 2020 were similar to those of men. Lee et al. (2021) find that women's employment declined more, early in the pandemic, but these differences dissipated by the end of 2020. Blanchet et al. (BSZ) (2022, p. 69) found that men's income dropped more than women's during the initial period of the pandemic; by the end of 2021, however, there was little overall change in gender inequality. In their analysis, BSZ divided the income of married couples equally between the spouses; researchers focusing on the labor income of individuals tend to find worse outcomes for women early in the recession.

Women's earnings disadvantage among prime age workers occurred largely because mothers suffered a greater decline in employment than fathers or non-parents during the pandemic recession. Alon et al. (2021) show that the US had a particularly large decline in women's employment compared to other advanced economies for which data were available (Canada, France, Spain, Germany, the Netherlands, and the UK). Most of the employment decline among women in the U.S. and Canada occurred among mothers who were not college graduates. Mandatory closures of schools and child-care centers were a contributing factor early in the pandemic, and the effect of closures continued after they had ended (Russell & Sun, 2020). Goldin (2022) characterizes stresses that women and families faced, and generally finds that the greatest differences were not between the sexes but between the more- and less-educated.

Alon et al. (2021) also find that U.S. women reduced their hours more than men in occupations unsuitable for work from home. They find qualitatively similar results in the UK and the Netherlands, where data on work from home are also available. Most workers in occupations unsuitable for telework are women, and they suffered disproportionate employment declines in the pandemic (Albanesi & Kim, 2021). Focusing specifically on mothers, Lofton et al. (2021) report that mothers working in occupations with flexible work schedules lost relatively few jobs during the pandemic. Furman et al. (2021) pointed out that mothers of young children (under 13 years) make up too small a share of the labor force to have a great impact on overall labor force participation and employment.

Minorities and marginalized groups

Categories of marginalized groups differ across cultures. Differences by ethnicity, race, immigrant status, indigenous status, disability, or sexual orientation can exclude workers from the employment mainstream. Such workers often have low incomes and have poorer medical care. We discuss selected findings here, and disability in our section below on long term impact, but a comprehensive discussion of marginalized groups is not feasible due to data limitations.5

In general, minorities had greater economic losses from the pandemic in its first months. In the early pandemic period (through June 2020), Milovanska-Farrington (2021) found that the decline in U.S. Black employment was 0.6 percentage points greater than the decline for Whites, and that the increase in the share employed but not at work was 0.9 percentage points higher. Corresponding numbers for Hispanics were 2.4 and 0.9 percentage points. (These figures are adjusted for age, education, and other demographic characteristics.) Hershbein and Holzer (2021) find that Blacks and Hispanics lost more employment than Whites, though the difference for Blacks was small by December 2020.6 Blanchet et al. (BSZ) (2022, p. 34) find roughly parallel paths for pre-tax income of Blacks, Whites, and Hispanics during the pandemic and recovery.

Labor market outcomes for immigrants followed the same general pattern as other minority groups, both in the U.S. and in Europe. In the early months of the pandemic immigrants in both areas suffered large declines in employment relative to natives (Borjas & Cassidy, 2023; Fasani & Mazza, 2023). Much of this disparity was due to differences in the feasibility of remote work between occupations. Employment relative to natives recovered quickly. In the U.S., the pre-pandemic difference between immigrant and natives returned to its previous level by the end of 2020 (Borjas & Cassidy, 2023). Mazza et al. (2022) note that in the EU “all [employment] indicators had recovered and reverted to the pre-pandemic trends” by July 2021 for both natives and migrants.

3.3 Difference between wealthier and developing countries

Wealthy and poor countries experienced the crisis quite differently (Miguel & Mobarak, 2022). Deaton (2021) examined aggregate data for many countries through December 2020. Richer countries suffered more pandemic deaths and lost more GDP per capita. Inequality between countries had narrowed since 2000, especially when countries are weighted by population. During the pandemic, population-weighted international income inequality increased largely because incomes in India declined.

Yonzan et al. (2021) estimate the amount by which 2020 and 2021 incomes were lower than pre-pandemic projections for each percentile of the global population. Their estimates assume constant within-country income distributions, but allow countries' incomes to grow at different rates, with consequences for the global income distribution. In both years, losses were largest for people between the 10th and 30th percentiles of income. Income recovery has so far been greater in the better-off countries, with the top decile enjoying the strongest recovery.

Labor force participation rates dropped more sharply in developing countries than in advanced countries (IMF, 2021, Fig. 1.7 and IMF, 2023b, Figure 1.1). Bluedorn et al. (2021) found that unemployment increased more in developing countries. In both advanced and developing countries, increases in unemployment were generally similar for men and women.

Workers in developing countries often did not have access to systems of social support that would enable them to stay home and avoid the pandemic. Goolsbee and Syverson (2021) show that in the United States, many people changed their behavior to avoid COVID, apart from any government mandates. Miguel and Mobarak (2022) point out that many people in developing countries, with less of a social safety net, did not have this option. The International Labor Organization (ILO) (2020) estimated that 2 billion people worked in the informal economy, largely in developing countries, and that 1.6 billion of these were significantly affected by COVID, leading to an estimated 60 percent decline in their income.

Developing countries have a smaller proportion of elderly residents, who would be more susceptible to dying from COVID. Developing countries also have a greater number of workers in the informal sector, less effective medical systems, reduced access to vaccines, and lesser access to overall resources to meet the many challenges of the pandemic. On balance, these challenges tended to lower incomes in poor countries in the COVID period, increasing inequality between countries.

4 Long run effects of the pandemic period

Some of the changes to employment brought about by the pandemic will be permanent. One major change is that telework has increased, which tends to benefit higher income groups and experienced employees relatively more7 and tends to reduce the number of people living and working in central cities. Careers can be scarred by the loss of good employment matches, but this effect does not seem to have been large in the industrial countries for which we have good measures. The pandemic interrupted schooling worldwide, and this will have a long run effect, particularly affecting students in developing countries. Government debt spiked, which will be harder for low-income countries to manage. Overall, these effects can be expected to raise income inequality along several dimensions.

4.1 Telework

The Covid pandemic dramatically increased the amount of telework, in many instances permanently. An estimated 34.5 percent of U.S. establishments increased telework for their employees in response to the pandemic (BLS, 2021). Among establishments that increased telework during the pandemic, 60.2 percent expect to continue when the pandemic is over. Worker expectations of post-pandemic telework increased between mid-2021 and early 2022 in 10 of 12 countries surveyed (Aksoy et al., 2022). Telework may directly benefit affected employers and employees, for example by increasing productivity and/or reducing costs of office space and commuting. In addition, telework can change where workers live, what they consume, and where they buy, and such changes may have distributional consequences.

A survey conducted by Barrero et al. (2021) reports that U.S. employers plan to conduct 22 percent of future work at home, about half of what the surveyed workers prefer. The authors examine five factors that will help sustain telework: (1) the stigma of working at home has been reduced; (2) inertia against telework was overcome; (3) workers and firms both invested heavily in fixed costs that facilitate telework; (4) some residual fear of closeness to others may remain; and (5) the pandemic spurred supportive technological advances.8 These authors believe that increased telework carries benefits that will accrue disproportionately to better-off workers. The authors additionally foresee large time savings from reduced commuting and substantial increases in productivity.

Davis et al. (2021) similarly conclude that sustained increases in telework will be large and most beneficial to higher-paid U.S. workers. They argue that the pandemic accelerated adoption of technologies that permanently raise many high-skill workers' productivity when working from home. They develop a model in which high-skill workers allocate their time between working at home or in the office. The model predicts that in the long run, high-skill workers will work from home much more than prior to the pandemic, and that this will widen inequality. The findings are consistent with other literature that finds that technical advances in production disproportionately benefit high-skilled workers. The pandemic data bear this out. In the pandemic period, work-from-home rates were highly correlated to education level. In the January 2021 Census Household Pulse Survey, graduate degree holders were 71 percent more likely to report that someone in their household was working from home than those with high school education or less were (Dey et al., 2021; Rothwell & Smith, 2021).

Telework increased more for higher-paid workers. Among workers in the highest quartile of weekly pay, the percentage of workdays worked at home increased from 34.4 percent in 2019 to 59.7 percent in 2021, while the corresponding increase was only 9.5 to 15 percent for workers in the lowest pay quartile (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2020, 2022).

Bonacini et al. (2021) reach similar conclusions for Italy: a long-term increase in telework favors male, older, more highly educated, and better paid Italian workers. Overall average pay increases, and inequality also widens. Bachelet et al. (2021) examine how increased telework affects German workers, concentrating on time and financial savings from reduced commuting, rather than on pay. Time savings are greater than financial savings. Some benefits accrue to workers at all income levels, but higher income workers gain more, so inequality increases.

Telework can be a useful accommodation for workers with disabilities. According to Schur et al. (2020), from 2009 to 2018, 5.7 percent of disabled workers in the U.S. worked primarily from home, compared with 4.6 percent of those without disabilities. The share was greater among disabled workers with mobility impairment (6.7 percent), those with “difficulty outside home” (7.2 percent), and those with more education. The authors found, however, that disabled workers were likely to work in occupations where telework was not common. Ne'eman and Maestas (2023) report that during and after the pandemic, as telework became more common, employment of people with disabilities increased notably.

The geographic distribution of employment changed during the pandemic because of telework. The effect of these changes on income distribution is unclear. Li and Su (2023) show that net migration shifts towards suburbs and smaller cities, with a disproportionate contribution from high-income households. Housing prices increased in areas with a large proportion of people working from home (Kmetz et al., 2022).

Increased telework among higher-paid workers shifts consumption of housing and other goods away from city centers and toward outer suburbs and smaller cities and towns. In the short run, this shift reduced incomes of workers who provided services in city centers. The long-run effects on income inequality are not clear.9 Telework is less common for the occupations and the telecommunications systems available in developing countries.

4.2 School interruption

The COVID-19 pandemic shut down schools across the globe, throwing educators and students into an unfamiliar world of virtual learning. It disrupted education for an estimated 1.6 billion students at its peak (World Bank, 2021). Such a widespread disruption led many economists to predict significant and long-lasting scarring effects, including learning loss (Blaskó et al., 2021), lower lifetime earnings (Azevedo et al., 2020), and increased inequality (Agostinelli et al., 2020).

A meta-analysis of 42 studies from 15 countries examined 291 estimates of learning loss (Betthäuser et al., 2023). They estimate that students lost 35 percent of a year's learning, with greater losses in math than in reading. Losses were more severe for students from families of lower socioeconomic status.10 This study also suggests that educational losses spiked early in the pandemic and then stabilized. Learning losses increased as more school was missed (Kane and Reardon, 2023; Schady et al., 2023). Jakubowski et al. (2024) showed that the duration of school closures had an important effect on mathematics scores, especially for lower-achieving students.

Studies agree that students suffered substantial learning losses during the pandemic. The Northwest Evaluation Association Center (NWEA) examined test scores for millions of students in the United States. Using these data, Kuhfeld et al. (2022) reported severe learning losses; that study also emphasized that high quality tutoring and summer instruction can make up for learning losses. A subsequent analysis (Lewis & Kuhfeld, 2022) mentioned that many students had begun to rebound and catch up on their lost learning. Unfortunately, for a while further work found little evidence that students were actually recovering their lost learning (Lewis & Kuhfeld, 2023). NWEA assessments are based on elementary school students. The influential 2023 U.S. National Assessment of Educational Progress is based on 7th and 8th graders. The important National Assessment data also did not find any sign of the rebound that initially appeared in the NWEA data.

However, recent evidence from state test data is beginning to establish solid evidence that U.S. students are recovering important portions of their learning losses. Halloran et al. (2023) report that the proportion of students who were regarded as proficient declined during the pandemic. They show that, by 2022, students had regained 37 percent of their losses of proficiency in math and 20 percent of their losses in English. Fahle et al. (2024) looked at test scores and showed that students recovered 32 percent of their losses in math and 26 percent in reading from spring 2022 to spring 2023. These studies provide important evidence of test score recovery.11

Across studies, learning losses were worst for low performing and minority students. The NWEA studies found that the largest learning gaps were found among minority students (Hispanic, Black, American Indians, and Alaskan Natives). Minority students seem unlikely to recover fully. Fahle et al. (2024) report, however, that some states or local areas were able to reduce learning losses substantially.

The pandemic, and the associated stress and family pressures, similarly hampered the development of pre-school children, who suffered significant declines in verbal, non-verbal, and overall cognitive performance compared to their pre-pandemic counterparts (Deoni et al., 2022).

Catch-up programs to help students recover from learning losses, such as tutoring or summer instruction, typically require substantial expenditures. Lower-income communities tended to have greater learning losses in the short run, and less resources for recovery. If many students do not make up their learning losses, then the pandemic will substantially reduce their lifetime incomes, increasing inequality, and a less-skilled workforce will lower future GDP (Hanushek, 2023; Jakubowski et al., 2024).12

Schooling losses in developing countries

A detailed World Bank study showed that learning losses were systematically greater in lower-income countries (Schady et al., 2023, Fig. 3.5). Lower-income countries faced worse educational challenges prior to the pandemic, generally experienced longer school closures, and were under-resourced and ill-equipped to offer remote learning.

A household panel survey of 19,000 primary-school-aged children in India shows a decline and recovery of educational performance (Singh et al., 2024). Specifically, they find that student math test scores declined 0.7 standard deviations and reading scores 0.34 standard deviations from 2019 to 2021. But two-thirds of this deficit was made up within 6 months of schools reopening. They attribute about a quarter of this rapid recovery to government-funded after-school remediation programs. There are not many other precise measures of education recovery in low-income developing nations.

Many developing countries have severe financial limits. Given their other needs, it may be difficult for them to find the resources needed to overcome learning losses. Jackson and Lu (2023) estimate shortfalls in GDP growth in the COVID period relative to prior IMF projections, and find that COVID's drag will last longer for lower-income countries, partly because of the shock to education.

4.3 Scarring of individual careers

In recessions, output growth usually slows down for many years, largely because many workers drop out of the labor force for long periods, and job displacement reduces both current and future earnings (Arulampalam et al., 2001; Martin et al., 2015). The effect on future earnings has been called scarring. After the covid recession, however, employment and labor force participation recovered relatively quickly in the industrialized countries.13 Incomes of most groups have recovered and the lowest 10 percent of workers obtained considerable real income increases.

It appears that relatively little career scarring occurred from the COVID recession, partly because it was brief. Schmieder et al. (2023) provide additional insight. Most such scarring occurs when workers are forced out of high-income jobs and must accept lower-paid jobs in other establishments. Many workers displaced during COVID were employed in low-wage jobs in hospitality and leisure or in retail trade. These jobs do not have a large positive wage premium that can be lost; workers displaced from these jobs are generally able to find similar employment elsewhere. Such wage losses increase with the duration of unemployment, and the COVID recession was relatively brief, so the process of scarring did not have much time to develop.14

The fact that labor force participation rates have recovered suggests that not much scarring occurred in the United States. This may be especially true for those, mostly women, who were forced to stay home to take care of children or others who could not go to school or to a day care center as usual. Many women could go back to work as soon as childcare centers or schools reopened. More generally, many workers retained a long-term connection with their employers.

Growth in many advanced countries has quickly recovered from the COVID crisis, suggesting not many workers were forced to drop out of the labor force permanently. These countries have on average returned to their earlier growth rates. The recovery has generally not gone as well for developing and lower income countries, where growth is still substantially below the rates the IMF projected prior to the crisis, raising the prospects for scarring in those countries (IMF, 2023b, Figure 1.1).

4.4 Government debt

Due to recession and increased expenditures, debt increased substantially in the pandemic in many countries.15 Developing countries were not generally as able to borrow through normal channels as rich countries were. Multilateral agencies, such as the IMF, the World Bank, and regional development banks, had to step in to help developing countries during the COVID pandemic. These loans helped to offset a collapse of government revenues and the withdrawal of private capital (Bulow et al., 2020, Chart 1); however, as a result, more countries are now near debt distress. The indebtedness of developing countries had grown prior to the pandemic (Estavao & Essl, 2020), but the increase in food and fuel prices associated with the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the worldwide increase in interest rates intended to slow inflation added to the burden of government debt in developing countries. These challenges will tend to increase income inequality across countries.

5 Conclusions

Many of the most-feared economic outcomes from the COVID-19 pandemic did not come to pass. There were concerns about scarring effects—that minorities and women would suffer permanent economic damage, that many workers would permanently drop out of the labor force, and that a generation of students would fall behind permanently. But it appears that labor force participation rates have returned to their previous levels, minorities and women returned to their previous earning levels, and the income of many of the lowest-paid workers actually increased. Output has grown rapidly since the COVID-19 recession. There is even evidence that some students are catching up on their lost learning.

For developed countries, the worst effects of the covid period were on lifespans and health rather than macroeconomic variables. Our evidence is not as clear for developing nations.

In the short run, lower-income and more disadvantaged groups generally faced more job displacement. These groups were more likely to hold jobs that require social contact, in sectors such as retail trade and leisure and hospitality that were forced to shut down or faced large reductions in demand. At least in the developed world, higher-income professionals, in contrast, often were able to shift to telework, preserving their incomes while reducing expenses. School and day care closures disrupted the work of many parents, particularly mothers. These changes threatened to widen income (and wage) inequality substantially, but short-term policy responses offset much of the shock to lower incomes, so that by some measures inequality actually declined. Since then, the labor market has largely recovered in the developed world, and major economic policy responses have lapsed.

We conclude that the pandemic is likely to widen income inequality over the long run. It brought about durable changes in work patterns that predominantly benefit higher income groups or erode opportunities for some less advantaged groups. Most importantly, telework has increased permanently, which changes the shape of urban areas, commuting patterns, and the number and type of jobs in urban areas. School disruptions have been worse for lower-income students and for lower-income countries, and are likely to have lingering negative effects, which will widen inequality within younger cohorts.

References

- 1 Evidence on how technology and trade reduced the employment of many middle-skilled workers is summarized in Piacentini et al. (2022). De Loecker et al. (2020) argue that the increased market power of large firms contributes to inequality. Ganapati (2021) showed that greater industry concentration in the United States is associated with a lower share of income paid to labor.

- 2 For further analysis of these differences, see Saez and Zucman (2020).

- 3 The debt-to-GDP ratio rose from about 93% to 118% in the U.S., and from 38% to 45% in Germany. Source: IMF DataMapper, Central Government Debt, September 2023. https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/CG_DEBT_GDP@GDD/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD/USA/DEU.

- 4 This comparison is made in OECD (2020). Tetlow et al. (2020) and Cantó et al. (2022) compare national policies of several countries and their effects.

- 5 Lindeman (2023) discusses data limitations in describing differences in the impact of COVID by race.

- 6 Hershbein and Holzer's employment measure does not include those who work part-time for economic reasons or are away from work for unspecified reasons. Adjusting for education and the quartile of the occupational wage has only a small effect (though they do not adjust for the work-from-home suitability of the occupation).

- 7 Emmanuel et al. (2023) found that remote work reduced the amount of feedback that junior or new engineers received and made them more likely to quit. These effects were particularly strong for female workers.

- 8 Bloom et al. (2021) report that the mix of U.S. patent applications shifted in 2020 to include larger numbers of innovations that support telework.

- 9 Badger et al. (2023) report that large numbers of college educated workers left large cities in 2020 and 2021. If these movers are participating in the digital economy from afar, their departure redistributes work away from large urban centers.

- 10 Blundell (2022, Section 2.1) reviews evidence from time studies that shows how much learning time British students lost during the pandemic (including education at home) and how much this proportion varies among different socioeconomic groups.

- 11 Miller et al. (2024) report on the Fahle et al. (2024) study in the New York Times for January 31, 2024.

- 12 Apprenticeships also declined during the pandemic, further reducing human capital (Blundell et al., 2022).

- 13 Blanchet et al. (BSZ) (2022, p. 27) report that the (working age) employment-to-population ratio was 78% before COVID, declined to 68% during COVID, but returned to its pre-COVID level by September 2022. There are some subtleties and exceptions (Bauer et al., 2023; Eurofound, 2022).

- 14 Barrett et al. (2021) show that scarring has been worse following recessions involving instability of financial institutions; they cause more job loss and slower recovery. BSZ find this to be the case for the Great Recession of 2007. Scarring would therefore tend to be worse in developing economies with weaker financial capabilities. This would widen inequality across countries.

- 15 International Monetary Fund (2023a, Fig. 3.1) .