Building a Values-Informed Mental Model for New Orleans Climate Risk Management

Abstract

Individuals use values to frame their beliefs and simplify their understanding when confronted with complex and uncertain situations. The high complexity and deep uncertainty involved in climate risk management (CRM) lead to individuals’ values likely being coupled to and contributing to their understanding of specific climate risk factors and management strategies. Most mental model approaches, however, which are commonly used to inform our understanding of people's beliefs, ignore values. In response, we developed a “Values-informed Mental Model” research approach, or ViMM, to elicit individuals’ values alongside their beliefs and determine which values people use to understand and assess specific climate risk factors and CRM strategies. Our results show that participants consistently used one of three values to frame their understanding of risk factors and CRM strategies in New Orleans: (1) fostering a healthy economy, wealth, and job creation, (2) protecting and promoting healthy ecosystems and biodiversity, and (3) preserving New Orleans’ unique culture, traditions, and historically significant neighborhoods. While the first value frame is common in analyses of CRM strategies, the latter two are often ignored, despite their mirroring commonly accepted pillars of sustainability. Other values like distributive justice and fairness were prioritized differently depending on the risk factor or strategy being discussed. These results suggest that the ViMM method could be a critical first step in CRM decision-support processes and may encourage adoption of CRM strategies more in line with stakeholders’ values.

1. INTRODUCTION

Mental models are internal depictions of the world that allow an individual to interpret observations, organize beliefs, and make decisions in different contexts.1 Mental models have long been used to analyze how the public uses scientific information and knowledge to form beliefs about risks like climate change.2 These beliefs are identified through a process of comparing two archetypal mental models: a layperson model and an expert model. Both models are constructed and reinforced through experience and social interaction; thus, laypersons’ models tend to be more practical and limited by the time and attention they can give a task,3 while experts’ models tend to be more theoretical or scientific, and thus more complex and systemic. Comparing the two models helps to identify crucial gaps in understanding—by both groups—and focuses communication and outreach on the most relevant and meaningful information individuals need to make informed decisions.4

Communicating the “right science,” or what the public most needs to know, is important because both experts and the public's resources are limited. However, many scientists have argued that even this “deficit model” of risk communication, or providing ever more accurate and relevant information to the public, is insufficient to generate appropriate concern or the decisions necessary to mitigate risks like climate change.5-7 This failing is likely due in part to the difficulties inherent in understanding climate change, i.e., its causes are invisible, its impacts are temporally and geographically distant, and its signals are hard to detect.8 A another perhaps more important cause may be that the public relies heavily on personal experience, affect, values, and worldviews to inform judgments5-7, 9, 10 and intuitions.11 Many of these factors are excluded from conventional methods of risk assessment and communication.5

A large body of literature purports the role of values and worldviews in determining climate-change risk perceptions and decisions.7, 12, 13 For instance, research shows climate change deniers prioritize “self-enhancement” values, such as valuing achievement or power,14 and individualistic and hierarchical worldviews.7 Environmental activists, however, tend to ascribe to more “self-transcendent” and “biospheric-altruistic” values,15 such as benevolence or prioritizing personal sacrifice for collective or long-term benefits. Similarly, egalitarian worldviews have been shown to positively predict climate change risk perceptions.7

Despite the important role values play in risk perception, most mental models about climate change remain “primarily cognitive,” focusing on what people know, or how people make inferences about its causes.7 Fischoff provides a rationale for this cognitive focus by arguing proper science communication must present individuals with a “shared understanding of the facts, then they can focus on value issues” (emphasis added).16 Perhaps as a result, few mental model studies acknowledge or attempt to illustrate the values underpinning the beliefs and opinions modeled. One that does so admirably is Lowe and Lorenzoni's study of experts’ perceptions of managing climate change.17 They illustrate where values such as human and ecosystem health, procedural justice, and fairness and equity may impact decisions, yet the authors’ “meta-mental-model-diagram” is complex and we believe difficult to operationalize.

Furthermore, presenting a “shared understanding of the facts” is problematic when the facts themselves are in dispute due to deep uncertainty. Deep uncertainty occurs when there are no agreed-upon probability distribution functions to represent uncertainties, no conceptual models that describe relationships among key driving forces in the future, no consensus of expert judgments or predictions, or little certainty about how to value the desirability of alternative outcomes or states.18 Deep uncertainty defines many climate change risk factors, as well as how climate risk management (CRM) strategies developed to mitigate those risks will perform.

Such uncertainty necessarily increases the importance of investigating people's values—even those of experts. For as uncertainty increases so too does the extent to which people rely on values to inform, interpret, and transform their knowledge of climate change and estimate their climate risk.17, 19-21 For instance, Bray and Von Storch argue that when uncertainty is extremely high, scientists often express views beyond their expertise and these views are influenced by their own personal interpretations and values.22 It has also been demonstrated that the performance of CRM strategies is especially sensitive to not only the current state of knowledge and beliefs', but also the model assumptions and parameters chosen by scientists,23 choices that are often driven by scientists’ ethical and epistemic values.24 Yet peoples' values are often deployed and prioritized differently in different contexts.20, 25 As such, it is important to understand the impact of different contexts on not only scientists', but also laypersons’ values—in particular, identifying how both group's value priorities might change.26

Identifying what people value and their value priorities in different contexts is not trivial. Individuals’ values are susceptible to various moral heuristics,27 biases such as naturalism and parochialism,28 and the relative values or positions of others.29 People's values are susceptible to peer pressure30 and can be used to rationalize and accept (or ignore) risk assessments of experts espousing similar (or different) values.31 CRM also demands people to make difficult tradeoffs between important and often incommensurable values, such as equity and efficiency,32 the effort (required) and effect (desired),33 cumulative risk versus the risk of the most vulnerable, and the value of human lives versus those of ecosystems. A number of these tradeoffs include values that are to some people “absolute” or “inviolable,” and thus “sacred,” requiring people to make deeply uncomfortable, even “transparently outrageous” decisions.34 Decades of decision science have shown individuals struggle to make these difficult tradeoffs.35

The combination of difficult tradeoffs, deep uncertainty, bias, and complexity lead to individuals’ values regarding CRM likely being coupled to and contributing to their understanding of specific climate risk factors and strategies.36, 37 Put differently, individuals (including experts) likely use one particular value or set of values to understand one climate risk factor (e.g., a specific aspect, impact, or attribute of climate change), or CRM strategy, while using a different value or value set to understand a separate risk factor or strategy. This proposition builds on Earle and Cvetkovich's salient value similarity model, which argues that specific values may be more important in certain situations than others or as the meaning of a specific situation changes.38 It is important to note that such a view is in opposition to those approaches39 that represent individuals as having an ideal worldview (such as individualism or hierarchism) in which they apply their dominant values consistently across most situations.31

To better account for both experts’ and laypersons’ values in CRM, we present an augmented mental model research approach here called the “Values-informed Mental Model,” or ViMM. ViMM deliberately elicits people's values alongside their beliefs about climate risk factors and CRM strategies. In doing so, ViMM attempts to make the relationships between complex sets of beliefs, values, risks, and CRM strategies more explicit. Structuring decision-making processes can assist in ensuring individuals consider and evaluate CRM strategies more thoroughly across all of their key objectives and concerns.40 However, ViMM's strength lies in identifying which values individuals typically focus on with regard to specific risk factors and CRM strategies. Defining these relationships we believe will improve risk managers’ communication efforts, as they will be able to focus or frame messages about specific factors or strategies using the most relevant values for each. We expect that incorporating ViMM will thus increase adoption of more effective CRM strategies through the recognition and use of more salient value frames.31

In the following sections, we describe our initial development and deployment of the ViMM method using New Orleans as a case study. We interviewed 16 individuals representing a diverse sample of the city's residents and coded those interviews to (i) identify key climate and environmental risk factors and CRM strategies, (ii) elicit the values these residents use to understand and evaluate specific risk factors and strategies, and (iii) construct a straightforward visual representation of the complex relationship between risk factors, CRM strategies, and values. The results suggest that participants used three values consistently (i.e., maintaining a healthy economy, promoting healthy ecosystems, and preserving New Orleans’ unique sense of place) to frame their understanding of many risk factors and CRM strategies, and that certain values like distributive justice and fairness or protection against floods were prioritized differently depending on the risk factor or strategy being discussed.

2. METHODS

2.1. Context: New Orleans, LA

Due to its substantial climate risk and the number of CRM strategies proposed to mitigate that risk, New Orleans presents a useful case study to test the ViMM method. Projections already suggest the city will face more frequent Category 4 and 5 hurricanes,41 rising sea levels,42 disappearing wetlands,43 and heat indexes that will begin to exceed thresholds more often each summer.44

Additionally, since Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans in 2005, a number of CRM strategies have been proposed and many completed, such as the Army Corps of Engineers raising and strengthening the levees in New Orleans to a flood protection level of 1 in 100 years.45 Other CRM strategies include rebuilding and restoring the state's coastline and marshes, improving nonstructural protection (e.g., elevating and flood-proofing buildings), relocating residents away from areas with high flood risk, and enhancing the city's evacuation procedures.46

A great deal of uncertainty accompanies both how these risk factors will develop and how the strategies proposed to mitigate them will perform. The climate risks are difficult to quantify across spatial and temporal scales47 and show subtle yet abrupt transitions and hysteresis responses.48 Additionally, predicting how CRM strategies will address people's values is dependent on projections of how residents’ values may evolve over time,49 and the climate model assumptions and parameters chosen by scientists.23

2.2. CRM Expert Model

The ViMM method begins by examining expert beliefs and values via literature reviews, content analysis, and semi-structured interviews with experts. These results are used to construct an expert ViMM as well as a semi-structured interview protocol from which to investigate both stakeholders’ beliefs and values, and construct a stakeholder ViMM. These two models, the expert and stakeholder ViMM, can then be used to conduct a value-based gap analysis, identifying inconsistencies in stakeholders' and experts’ beliefs and the values they use to discuss and understand those beliefs.

In this study we used interviews with 11 climate scientists from universities across the United States, interviews with three CRM experts who had lived in and had experience working in New Orleans, and an analysis of the Costal Protection and Restoration Authority's Louisiana Comprehensive Master Plan46 to develop our understanding and our stakeholder protocol. In both the interviews and the Master Plan analysis we identified relevant climate and environmental risk factors and CRM strategies for New Orleans (Table I). The specific values identified in the scientist interviews and the expert ViMM are the subject of another study and paper.50

| Definition | |

|---|---|

| Risk Factors | |

| Sea-level riseE | Rise in local or global sea levels due to factors such as melting ice and sea expansion |

| HurricanesE | Powerful storms that produce heavy rain and winds, characterized by a low-pressure center |

| Storm surgeE | Rapid rise of water typically generated by a storm or hurricane, over and above the tide levels |

| Coastal erosionE | Erosion of the south Louisiana coastline due to factors such as reduced deltaic sediment, oil and gas exploration and development |

| FloodingE | Overflow of water from Mississippi River, nearby lakes or bays, or as a result of extensive rainfall, often exacerbated by poor drainage systems or malfunctioning pumps |

| DroughtsP | Prolonged shortages in water supply due to below-average participation or high evaporation |

| Seasonal changesE/P | Shifts or changes in the duration or timing of common seasonal temperatures and weather patterns |

| Glaciers meltingP | Retreating glaciers due to factors such as increasing air temperatures |

| SedimentP | Sand, dirt, and particulate matter that is transported by the Mississippi River or the Gulf of Mexico |

| CRM Strategies | |

| Raising levees | Building levees and raising the heights of existing levees to decrease risk of flooding |

| Rebuilding land | Diverting sediment or sand to rebuild land and restore marshland and coastline to reduce storm surge |

| Nonstructural protection | Elevating homes and buildings to decrease their risk of flooding during or after hurricanes |

| Free Mississippi River | Letting the Mississippi River run free to prevent land from being lost and replenish the coast, i.e., intentionally removing levees |

| Relocating residents | Permanently relocating residents away from high flood risk areas close to the Mississippi and the Gulf, and restricting development in those areas |

| Warning & evacuation | Improving the region's ability to warn and evacuate residents |

| Improving insurance | Increasing and improving insurance coverage |

| Renewable energy | Switching to renewable fuels and technologies to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. |

| Solar radiation management | Changing the Earth's albedo, for example, by injecting particles of sulfur into the atmosphere to reflect the sun's rays and cool the earth |

- Note. Risk factors identified by experts are noted with an E and those identified by participants are noted with a P. Definitions were provided by the interviewed experts (please see the main text).

2.3. Stakeholder Interviews

Using the risk factors and CRM strategies identified in the previous step, we constructed an open-ended, semi-structured interview protocol divided into three main sections; see the Supplemental Materials for the full protocol (S1). The first section focused on participants’ knowledge of climate change and climate risk factors, both global and those local to southern Louisiana. The second section concentrated on participants’ knowledge of CRM strategies. The third section examined participants’ experiences with extreme weather events.

Each of these sections began with general questions designed to avoid encouraging participants to discuss specific risk factors, CRM strategies, or events (e.g., Hurricane Katrina). As the interview neared the end of each section, however, we prompted stakeholders, to speak about those risk factors, strategies, or events that had been identified by experts, but had not yet been addressed by the interviewees. At no point during the interview were participants prompted to explicitly discuss values or identify their values while thinking about or discussing specific risk factors or strategies. This was done to avoid priming individuals to think about and perhaps demonstrate values that they would not have done otherwise. The interviewer did, however, ask follow-up questions if a recognized value was introduced during discussion, such as “You mentioned ___, could you please speak more about that?”

The protocol was pretested using two individuals who had both lived in New Orleans, but had no knowledge of the current project or each other. Interviews took approximately 60–90 minutes.

2.4. Study Participants

We interviewed 16 individuals to develop the CRM Stakeholder ViMM. These individuals represent a diverse sample of New Orleans residents from different community and religious organizations, city government, fisheries, oil and gas, tourism and hospitality management, universities, and primary schools. We sought and contacted by phone or email prospective stakeholders identified by Internet searches of relevant individuals and organizations and by suggestions of the RAND Gulf States Policy Institute (New Orleans, LA).

Ten males and six females ranging in age from 30 to 70, with a median age of 45, comprised our sample. All participants lived in New Orleans for at least four years, some as long as 62 years, with a median length of residence of 16 years. Participants were not compensated. The 16 interviews were transcribed by Keystrokes (Santa Monica, CA).

2.5. ViMM Analysis

Mental models rely on identifying different concepts or themes, termed “nodes,” as well as co-occurrences between those nodes, within participants’ interview responses. These nodes typically represent different states of the world, uncertainties, or decisions, but are expanded to include values in ViMM research. In this study, two authors coded three distinct categories of nodes: Risk factors, CRM strategies, and Values. Coding is the analytical process of attaching labels to segments of interviews in order to identify the ideas, behaviors, beliefs, and perceptions contained within them.51 The result is a hierarchical coding system of categories and concepts, as well as the number of times each concept is mentioned, i.e., the node's frequency. Calculating frequencies is considered essential to fully understand conceptualizations of the three categories51 and is an accepted indicator of how significant a concept is within the overall structure of a mental model.4

We identified nodal co-occurrences, i.e., when two concepts or themes were discussed concurrently, during the course of a single participant's response. A single participant could demonstrate multiple co-occurrences of the same two concepts (in different responses to different questions). We tabulated and calculated co-occurrences using a simple spreadsheet program, noting bi-nodal co-occurrences between the categories, Values and Risk factors and Values and CRM strategies, and between nodes within Risk factors.

In coding for values, the authors sought a balance between providing sufficient nuance with regard to the specific values demonstrated and ensuring high interrater reliability. We used one of the 16 interviews to calculate the interrater reliability of two coders, achieving a Cohen's Kappa, or κ, = 0.70, indicating sufficient agreement,52 and subsequently removed that interview from analysis, resulting in n = 15. Fifteen interviewees is sufficient for reaching data saturation using standard mental models approaches,53 and was sufficient here to reach saturation with regard to the values used by participants to understand risk factors and CRM strategies. However, we caution that additional interviews and confirmatory surveys would be required to more accurately represent how a diverse community deploys specific values, and their prevalence, across risk factors and CRM strategies.1

3. RESULTS

Both the experts and stakeholders identified a range of environmental and climate risk factors that would affect New Orleans, the United States, and other regions around the world. Table I describes these factors, as well as the nine CRM strategies proposed by our experts and the CPRA's Louisiana Master Plan46 to be discussed by our stakeholders (no additional strategies were introduced or discussed by stakeholders). The values articulated by our stakeholders are listed in Table II.

| Values | Prevalence | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Nonhuman welfare | 100% | Temporally undefined concerns about the nonhuman distribution of impacts, risk, or strategy benefits, e.g., on ecosystems or biodiversity |

| Sense of place | 100% | Importance of New Orleans as a unique cultural resource, discussion of place-based traditions, cultures, and historically significant neighborhoods or communities |

| Economy | 100% | Importance of income, wealth, and jobs as component of welfare, value of a “working coast,” healthy fisheries, and oil and gas industry |

| Quality of life | 87% | Value of goods or services contributing to the quality of life, such as health, enjoyment, political stability, personal freedom |

| Flood protection | 87% | Intrinsic value of protection from hurricanes and floods as a result of coast or levees; sense of safety and comfort that comes from being protected |

| Empowerment | 87% | Value of social mobility and education, importance of improving individuals' knowledge, socioeconomic status and ability to make better choices, such as via technology or innovation |

| Engagement | 80% | Concerns regarding how decisions are made and by whom, discussion of proper representation for those who have a stake in the outcomes of CRM decisions |

| Sustainability | 80% | Importance of actions that sustain, i.e., do not put undue stress on, natural resources or systems, discussion of "green" actions, technologies, or philosophies |

| Basic needs & survival | 80% | Importance of goods or services that are necessary for survival such as food, water, shelter, clean air, services for the elderly; concerns regarding losses of life |

| Distributive justice | 67% | Contemporary concerns about the distribution of climate impacts, risk, or strategy benefits on human beings |

| Fairness | 47% | Concerns regarding a more specific and subjective experience of distribution, discussion of the undue burdens placed on portions of the population that have been historically treated unfairly (a more severe form of distributive justice) |

| Intergenerational justice | 40% | Concerns about the distribution of impacts, risks, or strategy benefits across time and on past and future generations |

| Population growth | 13% | Importance of demographic renewal of New Orleans population, both post-Katrina and future |

- Note. Prevalence represents percentage of participants who evinced the value in discussion of risk factors or CRM strategies. Definitions were developed based on participants' responses.

3.1. Risk Factors

The risks identified (Table I) include both those factors suggested by scientists, CRM experts, and the literature to be considerable risks to New Orleans over the next 100 years, i.e., sea-level rise, storm surge, (more frequent or severe) hurricanes, coastal erosion, flooding (as a result of overtopping of the Mississippi River and/or rainfall) and seasonal changes, and three factors introduced by participants. The latter included droughts, glaciers melting, and changes in Mississippi River sediment (its composition and flow). Experts did not identify these risk factors as representing considerable risks to New Orleans. Despite identifying these additional risk factors in their discussion, no participants identified any as their greatest concern. Instead, seven participants identified sea-level rise as the risk factor with which they were most concerned; three identified coastal erosion; two identified hurricanes; one identified seasonal changes; and two participants did not identify a top concern.

3.2. CRM Strategies

The CRM Strategies (Table I) identified include seven regional adaptation strategies proposed to mitigate the above risk factors, many of which are noted by the CPRA,46 one climate change mitigation strategy discussed often by both scientists and CRM experts and participants, i.e., transitioning away from fossil fuels and toward renewable energy, and one climate engineering strategy, solar radiation management (SRM), identified by experts.

Before the interviewer introduced the CRM strategies listed in Table I, participants were asked to identify the CRM strategy that they would most like to see employed to mitigate their greatest climate-change-related concerns. Eight identified rebuilding land, or coastal restoration, two identified renewable energy and one identified relocating residents. Two participants did not identify a strategy and two spoke about the need to further educate students and the public about climate change—education was coded as a value, empowerment, instead of as a strategy (more on this in Section 3.3.). Note that no participants identified raising levees as their most preferred CRM strategy.

3.3. Values

Coding of the stakeholder interviews identified 13 distinct values (see Table II) that participants articulated when describing different CRM strategies and risk factors. Some of these, such as distributive justice, intergenerational justice, and fairness, are clearly ethical values. Others, such as economy and population growth, are social values. Per Young and Mack, a social value is a person's assumption, largely unconscious, of what is right and/or important 54—quality of life and nonhuman welfare are likely mixtures of ethical and social values depending on the respondent. This definition was used to distinguish between principally environmental impacts, i.e., Risk factors, the operational or decision concepts that mitigate those impacts, i.e., CRM Strategies, and the Values that participants held to be threatened by the former and protected or promoted by the latter. Such a distinction encourages CRM that accounts for both the physical and environmental impacts and what are more often ignored, the social impacts,55 which here we coded as values. For example, a person typically does not fear the risk factor coastal erosion unless that erosion threatens something he or she values. Nor does a community spend resources raising levees solely for the sake of the levees—a levee alone holds no intrinsic value. Instead, a community builds a levee because it promotes investment (economy), protects a historically significant neighborhood (sense of place), protects lives (basic needs and survival) and the quality of lives (quality of life), or ensures a technical college can continue to educate young community members (empowerment).

All 15 participants identified three values consistently across their interviews. The first was the importance of income, wealth, job creation, and maintaining a “working coast” (economy). For instance, participant #13 argued, “if it's critical infrastructure and people are able to get to the places they work that are strategic and necessary investments based on our economy I'd support that development.” Next, participants identified the importance of New Orleans as a unique city and cultural resource (sense of place). Participant #7 identified what people find when they arrive in New Orleans: “They come, they fall in love with the city, they find it unique to other places. This is very much a small town and it's like nothing but opportunity.”2

The third value participants consistently demonstrated was the importance of limiting impacts to and investing in ecosystems and biodiversity (nonhuman welfare). For illustration, here participant #10 identifies his concerns about the former when rebuilding land, “it seems like a good idea, but I'm neutral because I don't really know what a marsh conservationist would say about that. It seems, again, like we've got to do it, but I don't know if what grows in that place actually is a useful ecosystem, or if it's just another version of a man-made levee where we do it to protect the houses that are right there.”

The fourth most demonstrated value, along with quality of life and empowerment, was flood protection. It quickly became clear during the interviews that Louisianans have a unique relationship with the Mississippi River, the Gulf of Mexico, hurricanes, and water in general, so much so that flood protection is not simply a means to protect or promote certain values, but is instead a value in itself. As such, we included it and coded for it as a stand-alone value, here denoting the sense of safety and comfort that comes from feeling protected from floods. Participants often displayed high levels of emotion when discussing flood protection. In a passionate defense of the recently installed $22 billion flood protection system, participant #2 urged that he and others not only support but “believe in flood protection and levees and flood barrier structures and flood gates” (emphasis added).

The remaining nine values varied in prevalence. The ethical value distributive justice was identified by 10 participants, fairness and intergenerational justice were identified by only seven and six participants, respectively, and only two participants identified the least prevalent value, population growth.

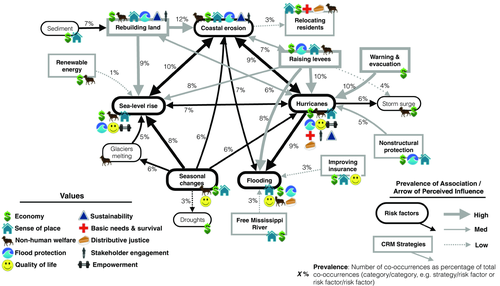

3.4. CRM Stakeholder ViMM

The CRM Stakeholder ViMM (Fig. 1) identifies the most prevalent co-occurrences and perceived influences between risk factors, CRM strategies, and stakeholders’ values. The stakeholder ViMM shows (a) the most prevalent risk factors (in bold), how participants perceive those risk factors interacting, i.e., hurricanes are associated with—they both influence and are influenced by—coastal erosion, (b) the most prevalent CRM strategies (again in bold) and which risk factors those strategies influence (not necessarily successfully), and (c) the values stakeholders use to understand, or frame, both risk factors and CRM strategies. For instance, the CRM strategy rebuilding land was associated most often with the risk factors coastal erosion, sea-level rise, and sediment. Raising levees most often co-occurred with hurricanes, sea-level rise, flooding, and coastal erosion. The stakeholder ViMM also shows the ratio of co-occurrences between two concepts as a percentage of total co-occurrences (between those concepts’ categories, i.e., Risk factor and CRM strategy (145 total co-occurrences), and Risk factor and Risk factor (190 total co-occurrences)). Thus, the highest co-occurring risk factors were coastal erosion and sea-level rise (19 of 190 co-occurrences), and the highest co-occurring risk factor and CRM strategy was rebuilding land and coastal erosion (18 of 145 co-occurrences). Solar radiation management is not shown in the ViMM because few participants understood it to a degree necessary to associate it with any risk factors or values.

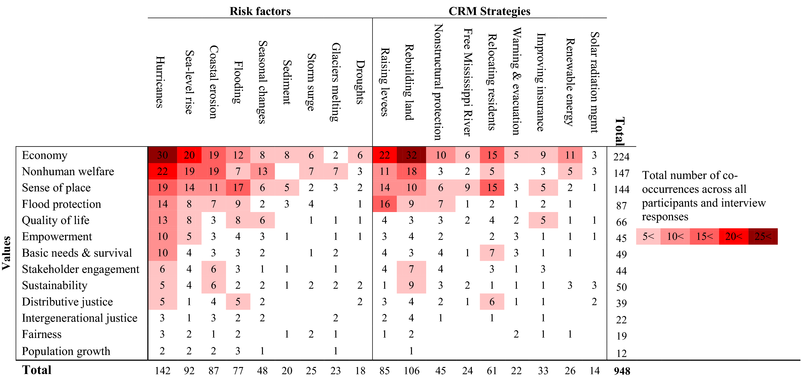

The ViMM also shows the most prevalent values (those with at least five co-occurrences) associated with each risk factor and CRM strategy. For example, the values most often associated with the risk factor seasonal changes were nonhuman welfare, economy, sense of place, and quality of life. The values most often associated with the strategy relocating residents were a sense of place, economy, basic needs and survival, distributive justice, and nonhuman welfare. The total number of co-occurrences between each value and each risk factor and CRM strategy is shown in Table III. The most prevalent value, economy, was associated with a risk factor or strategy 224 times across the 15 interviews, while nonhuman welfare, and sense of place showed the next most associations with 147 and 144, respectively. Population growth, the least prevalent value, was only associated with a particular risk factor or strategy 12 times.

|

- Note. Table shows the number of times each Value co-occurred with each Risk factor and CRM Strategy across all participants' responses.

Table III shows that certain risk factors and strategies were far more value laden than others. The hurricanes node was coded alongside a Values node 142 times, while the most value-laden CRM strategy was rebuilding land, with 106 value codes. Neither result is surprising considering Hurricane Katrina's effect on residents and the amount of controversy surrounding the CPRA's efforts to rebuild land.58

4. DISCUSSION

Both the ViMM method and the case study introduced above build off a primarily cognitive mental model risk communication approach to make the relationships between stakeholders’ beliefs, values, risks, and CRM strategies more explicit. While establishing what people know about climate change risk is certainly important—and here mental models excel,2 eliciting people's values alongside what they know is also critical. This is especially so when (i) deep uncertainty exists in predicting future climate change scenarios and their social, economic, and environmental consequences at a regional scale,59 (ii) high complexity describes the social and environmental systems involved, and (iii) difficult, often incommensurable, value tradeoffs need to be made. Each of these conditions describes CRM efforts both in Louisiana and elsewhere.8 As such, explicitly identifying the beliefs and values community members demonstrate with regard to risk factors and CRM strategies is critical, especially if our risk communication goals are to build trust,31 acknowledge risk analysts and communicators’ moral responsibility,60 bring more meaning to often impenetrable information,61 and encourage decisions more in line with people's values.5

Our results suggest that participants demonstrated a consistent set of beliefs and value frames to understand different risk factors and CRM strategies in New Orleans. First, regarding beliefs, most of the participants identified sea-level rise or coastal erosion as their top climate risk concern, yet participants often conflated their cause in discussion. Instead of identifying local sea-level rise as a result of the channeling of the Mississippi River and oil and gas exploration and production, participants often identified the direct cause of this rise and coastal erosion to be climate change. While perhaps convenient for those encouraging CO2 mitigation strategies, climate change is not yet the principal culprit of local sea-level rise or land subsidence in southeastern Louisiana, with recent work showing coastal erosion to be much more a result of local human impacts than global sea-level rise or climate change.62

Additionally, certain participants attested to New Orleans being a global leader in climate change adaptation. This despite the fact that the CPRA, which has been tasked with restoring Louisiana's coastline, uses the term “climate change” sparingly—it is used only once in its Master Plan Principles while “accounting for uncertainties.”46 While the CPRA's efforts and Master Plan will certainly—and intentionally—aid the city and state greatly in engaging climate change in the near and long term, such terms are rarely proffered publicly or used in official documents. Louisiana's land-building efforts are often presented as bolstering flood protection and reducing storm surge in the short term and stemming collapse of the delta in the long term, what the CPRA calls the state's plan for a “sustainable coast.”46

Regarding values, our participants rarely associated coastal erosion with the value flood protection, instead discussing coastal erosion and rebuilding land using one of three value frames: economy, nonhuman welfare, and sense of place; it should be noted that these values to a great extent mirror the three commonly accepted pillars of sustainability (i.e., economic development, environmental protection, and social responsibility). For example, some saw the rebuilding of land as a development opportunity that would create jobs; others worried about how the strategy would affect the health and distribution of fisheries and oyster beds (both from a nonhuman welfare and economic perspective). Few equated the strategy with addressing climate change per se. Participants’ economic focus raises an interesting dilemma for risk communicators: Do they commit resources to informing the public about the significant role humans play in wetland and coastal restoration62 and coastal restoration's complex role in reducing storm surge?43 Or do they frame their land-building efforts as a primarily economic strategy?

Similarly, risk modelers are working to incorporate more accurate measures of lives lost into their post-Katrina levee-breach forecasts, and have advised that such forecasts (which show comparatively high risks of fatalities when compared with other infrastructure risks) should raise risk awareness.64 However, such measures may not be what residents are most concerned about. While certainly our participants value their own lives and the lives of others, they only demonstrated moderate associations between the basic needs and survival value frame and hurricanes, and rarely associated storm surge or (inland) flooding with that value. Instead, participants often spoke of both hurricanes and flooding as a unique aspect of living in New Orleans, a nuisance that added to both the city's and their own unique sense of place.

When participants did speak about the physical threat of hurricanes and storm surge they often did so by focusing on the threat to other members of the community, particularly those who lacked the means to evacuate, applying value lenses—and emotions—that are often ignored in CRM, such as empathy, distributive justice, and fairness.5, 60 Here, improving warning and evacuation procedures, not raising levees, was often the recommended CRM strategy, with participants advising that greater care be taken to evacuate low-income, elderly, and disabled residents. While most participants were knowledgeable about the benefits of the city's “contra-flow” program, in which the highway lanes are reversed to aid evacuation, many participants voiced concerns about how residents without vehicles or a place to wait out hurricanes might fare. Interviewees used similar values to think about both nonstructural protection, or the raising of homes and buildings, again a strategy that was difficult on children and the elderly, and relocating residents. With regard to the latter, participants worried about moving communities that already had few resources, were the most vulnerable, and least likely to be affected positively by such a strategy.

Participants demonstrated as many sense of place values as they did economic concerns when discussing relocating residents, and almost always focused their concern not on themselves but on others. Such results provide additional evidence that evaluating strategies and crafting our risk communication messages to use both economic and ethical value lenses is critical.5 While measuring values and incorporating emotions into our CRM efforts adds additional complexity, a focus on incorporating community members’ most salient values and thus increasing the relevance and responsibility of our communication efforts should prove worth the additional effort.

5. CONCLUSION AND LIMITATIONS

Just as mental model approaches are designed to identify gaps in understanding, ViMM is intended to help identify gaps in the values used by both the public and experts to understand risk factors and strategies. This study reported on the values of only a small sample of residents of New Orleans, but suggests a framework by which one can construct a more explicit model of the public's and CRM experts' and climate scientists’ values. While our study focused on CRM, ViMM can be used to identify the values people rely on to understand other complex and deeply uncertain risks such as nuclear power and nanotechnology. One must note of course that any values gap is likely—though not necessarily—dependent on who is included in the elicitation. Experts living in New Orleans may demonstrate different values than experts living outside Louisiana, just as individuals living in New Orleans may demonstrate different values from individuals living elsewhere in the United States or abroad. For this same reason, we believe it is important to ensure a wide-ranging diversity within elicited groups in order to determine whether there are value gaps relevant to such factors as economic standing, gender, and race. At the same time, the way in which both the public and experts attach specific values to specific climate change risk factors may be consistent across certain communities. Additional work investigating these important questions is necessary.

Despite these questions, in constructing representations of the specific values used to understand risk factors and risk-management decisions, we believe ViMM goes a long way in informing decision-support processes, building trust between risk analysts and the public, and making risk communication and CRM decisions more values-relevant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank Alexander Bakker, Chris and Bella Forest, Greg Garner, Rob Nicholas, Jordan Fischbachs, and Gary Cecchine, as well as the area editor and two anonymous reviewers for their extremely helpful input. Of course, all errors and opinions are the authors' alone. This work was partially supported through the National Science Foundation through the Network for Sustainable Climate Risk Management (SCRiM) under NSF cooperative agreement GEO-1240507, the Penn State Center for Climate Risk Management, and the Penn State Rock Ethics Institute. Any conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding agencies.