Is Panama really your tax haven? Secrecy jurisdictions and the countries they harm

Conflict of interest: No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

Abstract

Secrecy jurisdictions provide opportunities for nonresidents to escape the laws and regulations of their home countries by allowing them to hide their identities. In this paper we quantify which jurisdictions supply secrecy to which countries and assess how successful countries are in targeting that secrecy with their policies. To that objective, we develop the Bilateral Financial Secrecy Index (BFSI) which maps the financial secrecy faced by 82 countries and supplied to them by 131 jurisdictions, thus providing the study of the world of financial secrecy with unprecedented nuance. We then use the BFSI to evaluate the progress of two recent policy initiatives designed to curb financial secrecy: automatic information exchange (AIE) and the blacklisting of noncooperative jurisdictions. By embedding the role of power in the center of our analytical framework, we reconcile the apparently conflicting findings of the existing literature on the effectiveness of these policies. We show that secrecy jurisdictions engage in selective resistance depending on whom they are dealing with, and that the hypocrisy of Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development member countries lies at the heart of the design and operation of the AIE system and the blacklisting exercise. We argue that focusing policy on the most relevant secrecy jurisdictions, which – despite its pivotal role in recent offshore document leaks – only rarely include Panama, would enable countries to more effectively mitigate the harm caused by financial secrecy.

1 Introduction

Successive leaks of confidential documents from offshore financial service providers have been on the front pages and in primetime news across the globe since 2013. They have shed new light on the harm caused by financial secrecy supplied by secrecy jurisdictions, that is, jurisdictions that provide opportunities for nonresidents to escape the laws of their home countries by allowing them to hide their identities. In addition to tax-related offences, illegal drug and arms trafficking, grand corruption, and money laundering have also been shown to thrive beneath the cloak of secretive shell companies and other financial secrecy vehicles (Obermayer & Obermaier 2016). For example, the Panama Papers, released in 2016, affected the valuation of firms around the world and caused a number of politicians to resign (O'Donovan et al. 2019). These revelations have strengthened commitments made by governments and international organizations to expand their efforts to address the financial secrecy that they face. Most notably, these policies include the blacklisting of noncooperative jurisdictions (European Commission 2017b) and cross-border automatic information exchange (AIE) on the capital income of nonresidents, which has resulted in a network of over 4,000 bilateral information exchange relationships as of May 2020 (Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development [OECD] 2020; Tax Justice Network 2020b). These efforts undoubtedly represent nominal progress toward financial transparency; however, it is not clear how much real financial transparency has been achieved and how it is distributed across countries.

This paper addresses the question of how successful countries are in targeting secrecy jurisdictions with their policies. In particular, are countries efficiently covering the faced secrecy with AIE and blacklisting? Are some secrecy jurisdictions managing to keep the secrecy they supply to other countries uncovered by these policies? AIE and its role in addressing collective action problems caused by small island tax havens has been discussed intensely in global tax governance literature, and AIE has been equated with financial transparency and hallowed as ushering in a new era after neoliberalism. For example, it has been established as successful with respect to reversing the downward trend in capital income taxation and offering new tax policy options for (re)embedding globalization (Hakelberg & Rixen 2020). Yet at the same time, recent research documented the continued diversion of aid monies to secrecy jurisdictions (Juel Andersen et al. 2020), and Ahrens and Bothner (2019) found evidence of persistent financial losses to tax havens. Meanwhile, detailed legal analyses and process-tracing studies cast doubts on AIE's effectiveness, especially with regard to the impact on tax evasion of high-net-worth individuals (Knobel & Meinzer 2014; Meinzer 2018). This has led to the likening of the AIE standard to a “sham” or double standard (Meinzer 2019) in an adapted typology of regulatory coordination (Drezner 2005). Bearing these divergent views in mind, in this paper we seek to reconcile the apparent simultaneity of successful international tax cooperation and continued resistance by secrecy jurisdictions.

We answer our research question by introducing a new tool that allows us to analyze the role of power in the world of financial secrecy: the Bilateral Financial Secrecy Index (BFSI). We build the BFSI on the basis of the original Financial Secrecy Index (Cobham et al. 2015) by implementing one key innovation: moving the unit of analysis from an individual jurisdiction to bilateral dyads (i.e. country pairs). This approach enables us to capture the reality that individual secrecy jurisdictions are important for different sets of countries. We then use the BFSI to evaluate two recent policy efforts to curb financial secrecy: the EU's lists of noncooperative jurisdictions and the OECD's Common Reporting Standard (CRS) for AIE.

We arrive at three main findings. First, we find that more secretive jurisdictions manage to keep more of the secrecy they supply to other countries uncovered by AIE via engaging in a strategy of selective resistance. Among those highly secretive jurisdictions, the OECD's dependent territories play a crucial role. Second, we report that OECD countries are better than other countries at using AIE to target their most relevant secrecy jurisdictions. Third, we show that EU member states are better at targeting their most relevant secrecy jurisdictions with AIE rather than by means of blacklisting. Overall, our findings suggest that hypocrisy lies at the core of both the OECD AIE system and the EU's blacklisting exercise.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. The second section reviews the literature on global tax governance with a focus on the role of power and derives three hypotheses that we empirically test in the subsequent sections. The third section introduces the data used, explains the construction of the BFSI and the research design used to test the hypotheses. Section four presents the main findings, and section five concludes.

2 Closing the back door to power in tax haven research

A key puzzle permeating international political economy is whether or not secrecy jurisdictions are capable of resisting or escaping coercive measures implemented by powerful countries, and, if so, why that is the case. Rational choice institutionalism has been a favored methodological lens for approaching the topic of international tax competition and tax havens. Operating under the assumption that international institutions are designed rationally, early research had attempted to explain why collective action against tax havens has apparently been failing despite theoretic modeling indicating an overarching interest on the part of powerful countries to coerce or induce cooperation by tax havens. Dehejia and Genschel (1999) argued that a defection problem in international tax cooperation is exacerbated by the different sizes of individual jurisdictions. In this asymmetric prisoner's dilemma, small jurisdictions would not only have incentive to dodge cooperation, but – more importantly – would not find any cooperative arrangement desirable in the first place (p. 411). In addition, the feasibility of paying off tax havens for cooperation would be undermined by what the authors called an “outside world constraint” (p. 419). This weakest-link problem has been further analyzed by Elsayyad and Konrad (2012) who argued that tax havens that retain their business model the longest face less competition from other tax havens, increasing their model's profitability and further increasing their disincentives to cooperate. Using a similar methodological approach enriched by historical process tracing, Rixen (2008) provided a complementary explanation for the lack of success of the OECD's efforts before 2008 to counter tax havens in their harmful tax competition initiative. He argued that the confrontation inherent in the asymmetric prisoner's dilemma has not been resolved through sanctions or compensations to induce cooperation, largely due to the OECD's deep involvement in the establishment and management of thousands of bilateral tax treaties; this role of the OECD has thus far constrained any reform proposals to piecemeal approaches which have left the treaty setup largely unaffected.

From a constructivist theoretical perspective, Sharman (2006) attributed the failure of the OECD's 1998 harmful tax competition initiative to small tax havens successfully mobilizing shared regulatory norms in their favor. By alluding to the cartel interests of OECD member states to protect their financial centers against smaller nonmember competitors, they successfully fended off the OECD's attempts to impose tax rules on them as hypocritical. Webb (2004) complemented Sharman's account of normative constraints by pointing out the role of liberal economic ideology and the fiscal sovereignty principle which small tax havens and libertarian nongovernmental actors successfully appealed to in discussions with the new US government. The Bush administration finally withdrew its support from the existing OECD initiative in May 2001 and ended up truncating its scope to transparency and information exchange (pp. 813–814).

Since then, a number of different strategies employed by tax havens in order to resist global regulatory efforts have been scrutinized. For example, Eccleston and Woodward (2014) criticized the OECD's system for information exchange upon request as dysfunctional. Informed by literature on the politics of bureaucracies, the authors consider this system as a lowest common denominator standard which is failing to meet intended outcomes, yet is rolled out by an international organization because “[…] ‘success’ is often judged in terms of reaching an international agreement rather than its ultimate effectiveness […]” (p. 227). OECD information exchange policies invited mock compliance by tax havens because they allowed a standard which was inadequate for dealing with the problem of tax evasion in principle to be rolled out nonetheless (Woodward 2016). Woodward argued that this problem largely persisted even after the tightening of the system through a peer-review mechanism in the wake of reforms implemented following the global financial crisis of 2009. This general skepticism has been confirmed by economists who have evaluated the system for bilateral information exchange upon request. For instance, Bilicka and Fuest (2014) found that tax havens systematically undermine the information exchange framework by cherry-picking, that is choosing mainly irrelevant partner jurisdictions for exchange agreements to comply with requirements for a minimum number of signed treaties while avoiding the establishment of information exchange with more relevant partners. Where relevant relationships had been established, Johannesen and Zucman (2014) found evidence of shifting of bank deposits to secrecy jurisdictions not covered by a treaty with the depositor's country of origin.

2.1 Conflicting empirical findings in AIE literature

Since 2013, the advent of AIE at the OECD and G20 levels has been overwhelmingly heralded in international political economy literature as a game changer in the global fight against tax havens. The fast-growing body of literature on AIE can be broadly categorized as belonging to one of two strands according to their dependent variable. The first strand focuses on the output of the information exchange regime, that is the rules and system design, while the second analyses the indirect economic or policy outcomes of the system, that is the location and amounts of cross-border financial investment or related tax rates. A more direct and complementary measurement of the system's outcome in terms of its fiscal effects (i.e. increased tax revenue) has not yet been undertaken, as the required detailed statistics on both the exchange practice (output) and related tax revenues (outcome) are not currently available.

In the first strand, focusing on the regime's output, Emmenegger (2017) and Hakelberg (2016, 2020) traced the breakthrough for AIE to the UBS tax evasion scandal in 2008 after which US law enforcement successfully used US structural power over the international financial system to extract concessions from Switzerland. The United States has been successful in overcoming traditional Swiss resistance to compromising its bank secrecy rules because it was able to threaten Swiss banks with sufficiently credible sanctions. These legislative reforms then paved the way for others, including the EU and the OECD, to exact AIE from Switzerland. Meinzer (2018) argued that another obstacle for the further expansion of AIE was removed after the Swiss proposal for an alternative system of bilateral anonymous tax agreements had been stopped in the German legislature in 2012. Emmenegger and Eggenberger (2018) argued that a complementary reason for the success of the US strategy was its ability to rely on legal action by its law enforcement agencies rather than only on direct political confrontation with the Swiss government. Palan and Wigan (2014) as well as Eccleston and Gray (2014) and Lips (2019) confirmed a potential watershed moment in international tax cooperation through the Foreign Accounts Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) but also consider the implications of its unilateral design.

Other contributors to the first strand of literature identified loopholes in the AIE legal framework which could potentially facilitate exploitation by secrecy jurisdictions. Crasnic (2017, 2020) identified four different resistance strategies employed by small tax havens in the face of regulatory regimes, including in the new AIE regime. Categorized by the intensity and visibility of the resistance strategies employed, she argues that resolve and capability determine whether jurisdictions engage in submission, foot-dragging, rejection, or disruption. Knobel (2016) and Meinzer (2018) explored the repercussions of the lack of reciprocity in US FATCA. They argued that the United States succeeded in obtaining information to counter the tax evasion practices of its residents from all secrecy jurisdictions worldwide while refusing to participate in multilateral AIE and abstaining from reciprocating the same information on nonresident investors in the US financial system. Some of the international agreements implementing FATCA even contain the explicit acknowledgement that the United States needs to further amend its laws to reciprocate information exchange. Lesage et al. (2020) suggest that the lack of reciprocity by the United States in FATCA may have been a motivating factor for BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) countries to accept joining the multilateral AIE regime designed by the OECD.

However, specific concerns regarding loopholes even in the OECD's multilateral AIE regime, rolled out in 2013 as the CRS, persist. The CRS operates on the basis of a multilateral framework agreement signed by over 100 jurisdictions and resulting in a web of over 4,000 bilateral information exchange relationships as of May 2020 (OECD 2020; Tax Justice Network 2020b). Persistent private sector advertisements by law and asset management firms (Tax Free Today 2018; Macfarlane 2020), detailed legal analyses as well process tracing studies on the design of the AIE system suggest that loopholes in the CRS system are exploitable and that they are promoted by firms specializing in catering to high-net-worth individuals (Meinzer 2018). Examples include golden visas, carve-outs for active companies, low levels of sanctions for willful misreporting, as well as the absence of public registers of beneficial and legal owners of shell companies, trusts, and foundations (Knobel & Meinzer 2014; Knobel & Heitmüller 2018). The lack of public statistics on the system's output performance and the OECD's reluctance to make them mandatory constitute grounds for skepticism regarding the system's impact (Henn 2015; Knobel 2020).

The second strand of IPE literature focuses on the indirect economic and policy outcomes of the AIE system, that is the effectiveness of the multilateral AIE regime. As for the economic impact of AIE, most studies document a sizable effect where the value of deposits and portfolio investment in secrecy jurisdictions is reduced relative to nonhavens. A minority of studies, on the other hand, fail to find evidence of a deterrent effect of AIE on deposits from developing countries or argue that the heavy reliance on arbitrary binary listings of secrecy jurisdictions used as independent variables in some of the aforementioned quantitative research designs reduces the robustness of these economic impact findings, or that the implications of a reduction of “offshore” deposits for global tax evasion are ambiguous.

Beginning with FATCA, Hakelberg and Schaub (2018) found empirical evidence that the United States had successfully coerced smaller tax havens into AIE. After the passing of FATCA in 2010, they observed a substantial fall of international bank deposits in a handful of tax havens when compared to nonhavens. However, they also found an important effect of the hypocritical asymmetry in US FATCA (see discussion above: Knobel 2016, Meinzer 2018). They showed that deposits in the US financial system grew much faster than in other countries after FATCA was enacted (2010–2014). The authors thus identified a redistributive impact of FATCA, suggesting that the United States' refusal to reciprocate AIE increased its attractiveness for capital formerly hidden in secrecy jurisdictions. Casi et al. (2020) broadly confirmed these findings about the United States and presented evidence of an 11.5 percent short-term decrease in bank deposits by residents of nonhavens in secrecy jurisdictions which had adopted the CRS. In line with these findings, O'Reilly et al. (2019) found that AIE has led to a reduction of deposits in international financial centers.

In contrast with Hakelberg and Schaub's (2018) findings on the effects of FATCA, Ahrens and Bothner (2019) did not find evidence of a continuing shift of assets from tax havens into the United States following the introduction of the CRS. However, they did identify a relative decline of assets in tax havens compared to nonhavens. The effect of a relative decline of assets invested in tax havens compared to nonhavens was found to be triggered only by the unilateral announcement of the introduction of AIE by a given jurisdiction, and not by the actual enacting of a specific bilateral exchange agreement, either by these agreements entering into force or by the actual first exchanges of data happening.

Beer et al. (2019) provided a comprehensive review of a broad range of information exchange mechanisms, including information exchange upon request and three AIE systems (the European Savings Tax Directive; FATCA; CRS). They found that only AIE, and not information exchange upon request, has had an impact on cross-border deposits in secrecy jurisdictions, and that the impact of FATCA was relatively weaker than that of the other AIE regimes. Furthermore, the authors succeeded in overcoming the potential biases inherent in research designs that rely on arbitrary listings of tax havens, and inductively find that “offshore centers are typically (though not exclusively) characterized by low income tax rates (both personal and corporate), high financial secrecy, English as an official language, large FDI stocks, and small trade flows (both relative to GDP).” (p. 6). Most recently, Ahrens et al. (2022) analyzed the potential circumvention of the CRS through golden visas and anonymous trusts and shell companies. They found evidence of a limited use of these schemes (which appeared to grow over time) and concluded that, while rather contained at present, this type of regulatory arbitrage may become more prevalent in the future.

Finally, Hakelberg and Rixen (2020) analyzed the impact of AIE on policy responses in OECD countries. They explained an observed reversal in the downward trend of tax rates on dividend investment income with the introduction of tax information exchange in general and AIE in particular. Their findings showed that the exit threat, which tax havens had successfully projected into policymakers' minds in the past, appears to have lost some of its luster, and no longer constrains them from increasing tax rates on investment income. They attributed these changes to the new information sharing cooperation for enforcing personal income taxes on cross-border investment income, and interpret it as an important marker for a departure from a neoliberal era of anticipatory obedience in tax policymaking when policymakers felt they had no alternative but to lower tax rates.

In contrast to these studies, which interpreted the observed economic and policy impacts caused by the AIE regime to broadly imply a reduction of offshore tax evasion, others interpreted the findings more cautiously or made altogether different observations. In particular, Beer et al. (2019), whose analysis of the empirical evidence of the effects of AIE is arguably the most comprehensive to date, cautioned against interpreting the observed deposit reductions in secrecy jurisdictions as clear-cut evidence for a reduction of offshore tax evasion, “[…] since a reduction in presumably tax evading deposits in one offshore jurisdiction could imply an increase in tax evading deposits elsewhere.” (p. 27). A similar call for caution was expressed by Casi et al. (2020) who interpreted their findings as a change in the dynamics of cross-border tax evasion rather than as its end. Furthermore, Juel Andersen et al. (2020) provided evidence that aid monies disbursed to developing countries coincide with increased deposits in secrecy jurisdictions, a trend that has continued despite the secrecy jurisdictions' growing participation in AIE, suggesting a limited impact of AIE on the tax evasion of residents of developing countries.

2.2 The missing link: Placing power at the center stage

How can we reconcile these apparently conflicting findings on AIE effectiveness? And, furthermore, have secrecy jurisdictions stopped resisting the new AIE regime? We argue that in order to answer these questions we must consider power relations on two levels. First, we proceed to demonstrate how power differentials in bilateral relations can help reconcile the apparent contradictory findings on AIE effectiveness because secrecy jurisdictions engage in a strategy of selective resistance. Second, we argue that hidden power relations permeate much of the aforementioned literature on AIE and are at the center of (black)listings of tax havens and the global AIE policy regime design.

From the outset, two important design features of the CRS regime have served as a means to reduce benefits for, and to exclude or delay the inclusion of, lower income countries (Crasnic 2020). First, the dating system of bilateral exchange partners provided for a pseudo-multilateralism that allowed for bilateral power differentials to result in the cherry-picking of exchange partners, which for example Switzerland announced explicitly to exploit (Meinzer 2019). Second, the strict insistence on data exchange reciprocity even for lower income countries resulted in their delay or exclusion: none of the “least developed countries,” as defined by the United Nations, received information through AIE as of November 2019 (United Nations Department for Economic and Social Affairs 2020, p. 44). A survey among developing country officials in 2014 found that these design features were decided by the OECD before consulting with them, and were found to be contradictory to their expressed preferences (Meinzer 2019, pp. 98–102). The standard setting power enjoyed by the OECD and its members have thus dominated the design of the CRS system without incorporating developing countries' preferences.

These power relations vested in the CRS system also affect the strand of AIE literature which focuses on AIE effectiveness, and they often remained omitted from these studies' research designs. An important avenue for the omission of power to taint research is through tax haven lists which are used as independent variables in many econometric analyses in this literature. By relying on what Haberly and Wojcik (2014) label the “‘expert agreement’ definition of tax havens,” the definitional power over which countries are and which are not considered tax havens is omitted from critical scrutiny.

Tax haven blacklisting, both as a policy and as a binary variable used in empirical research, has been extensively criticized in the literature for the insensitivity to power inherent in the exercise due to its reliance on an oversimplifying dichotomy, its time lags, and its long poor track record in addressing the underlying problems of tax evasion and avoidance (Cobham et al. 2015; Meinzer 2016; Lips & Cobham 2017). A key reason for the failure of blacklists is the power relations network which shapes the listing efforts and results in settling for the smallest common denominator, scapegoating small and usual suspects, and omitting powerful secrecy jurisdictions and their dependencies despite their high levels of secrecy. A recent literature review by O'Reilly et al. (2019) revealed that most lists omit important UK dependencies such as the Cayman Islands and Bermuda or rapidly rising secrecy jurisdictions such as Mauritius and the United Arab Emirates, both of which are relevant especially for Asia and Africa (Tax Justice Network 2020c, 2020d). As a result, the findings of these studies (e.g. Johannesen & Zucman 2014; or Ahrens & Bothner 2019) may be highly sensitive to the list of chosen tax havens; furthermore, their robustness may be additionally constrained by the limited data available from those tax havens. In addition to the widespread use of listings in research designs, blacklisting exercises have not disappeared from the policy and rhetoric menus of national governments and international bodies, as the ongoing EU blacklisting exercise exemplifies.

We proceed to embed power in the center of our analytical framework. To this end, we adapt Drezner's (2005) typology of regulatory coordination to introduce a typology of international tax policy coordination in Table 1. Using this typology inspired by the dependency theory, we would expect a sham or double standard to emerge in the realm of AIE. This is due to two reasons. The first involves the substantial heterogeneity in preferences within the group of core states (mainly OECD members, but potentially also other countries that played an important role in the design of the AIE system) between those invested in the secrecy business and others. Although recent developments (which we discuss above and which forced secretive countries within the OECD such as Switzerland into multilateral AIE, while allowing Switzerland to dilute the standard) have led the group toward more homogenous preferences and a low-conflict scenario, we argue that the divergence of preferences was externalized onto OECD members' dependencies and overseas territories, which are generally more secretive. The high conflict scenario among core states (if we include dependencies in that group) thus persists even after the standard was shaped in a high-conflict context. Second, as the stock of tax-evading capital of residents of developing countries tends to be stored predominantly in the banks of developed countries, we argue that there are divergent interests with respect to AIE between rule-setting (OECD) and rule-taking (non-OECD) groups of countries. Ndikumana and Boyce (2018), for example, estimate that 30 African nations suffered US$1.8 trillion in accumulated stock of capital flight between 1970 and 2015, while the stock of debt owed by these countries as of 2015 was just over a quarter of the stock of capital flight assets (US$496.9 billion) held abroad, making the continent a net creditor to the world. Overall, we expect both sets of preferences (among core states and between core and peripheral states) to diverge substantially, leading to sham or double standards in the AIE system.

| Divergence of preferences between core (OECD) and peripheral (non-OECD) states | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| High conflict | Low conflict | ||

| Divergence of preferences among core (OECD) states | High conflict | Sham or double standards (or none/privatized) |

Rival standards |

| Low conflict | Club standards | Harmonized standards | |

We derive the following hypotheses from the above considerations and we proceed to test them empirically in the subsequent parts of the paper. First, under the CRS we expect highly secretive jurisdictions to be able to more successfully defend their “business model” by avoiding or at least delaying the activation of AIE relationships with countries to which they supply secrecy (thereby engaging in cherry-picking). Second, we expect richer and more powerful countries to be more successful than other countries at targeting their most relevant secrecy jurisdictions with AIE. Third, we expect the EU's lists of noncooperative jurisdictions to be less effective than AIE in targeting the secrecy jurisdictions that are most relevant to EU member states.

3 Dyadic analysis: BFSI

In this section, we introduce the BFSI as an innovate dataset enabling dyadic analyses with nuanced and verifiable data on the intensity of supply of financial secrecy. We proceed by describing the BFSI's underlying data sources, construction methodology, and selected results. We then introduce the additional data sources for policy analysis and our approach to using the BFSI for evaluating policies.

3.1 BFSI construction: Data and methodology

The BFSI builds on two key innovations over previous research. First, in line with the FSI, we replace binary classifications with more nuanced data on a country's level of financial secrecy offered to nonresidents. Assessing each country's laws and regulations transparently facilitates robust comparisons of the intensity of financial secrecy across jurisdictions and places each on a spectrum of secrecy, thus overcoming an artificial dichotomous distinction. This approach allows a more timely, nuanced and multidimensional view of financial secrecy by taking into consideration various secrecy tools which can plausibly help bypass or are out of scope of AIE, yet enable tax evasion and illicit financial flows. The inclusion of more nuanced and robust data instead of tax haven listings has become more established in research in recent years (Phillips et al. 2021; Ahrens et al. 2022; Killian et al. 2022). This approach allows us to better identify the potentially crucial role of power vested in the OECD and its dependencies in maintaining colonial types of economic domination and extraction.

Second, we change the unit of analysis from a unilateral one (i.e. single countries) to bilateral country pairs, taking into account that each secrecy jurisdiction is relevant for a different set of countries. For example, while Cyprus, a favorite destination for Russian depositors, combines both low taxation and high secrecy (Pelto et al. 2004; Ledyaeva et al. 2015), Mauritius has been notoriously secretive and important for multinational enterprises active in India and African countries as well as for African oligarchs (Beer & Loeprick 2020), and particularly relevant for incorporating shell companies (Fitzgibbon 2019). For the first time ever, the BFSI systematically captures jurisdictional dyads, opening up new avenues for econometric hypothesis testing.

The BFSI is composed of two parts which follow the methodology of the original Financial Secrecy Index. First, the qualitative part of the BFSI is composed of secrecy scores which measure the intensity of financial secrecy of each jurisdiction, and which we source from the original FSI in its 2020 edition (Cobham et al. 2015; Tax Justice Network 2020a). This dataset overcomes the blind spots of other previous research, which so far has paid scarce attention to domestic policies that may affect the functioning of the AIE system, such as the availability of golden visas, secretive trusts and shell companies, luxury free ports to hide wealth, or secretive real estate investment options. This landscape of potentially very harmful secretive instruments is highly dynamic not only because of new jurisdictions establishing secrecy hubs, but also because of secrecy jurisdictions' reactions to reform. In recent years policymakers have responded to various leaks by bolstering their domestic rules and regulations beyond AIE, for example with respect to the identification of the true owners of legal vehicles, the so-called beneficial owners (Fitzgibbon & Diaz-Struck 2016; Bowers 2019; Wilson-Chapman et al. 2019; Knobel et al. 2020). The secrecy scores capture this dynamic landscape as of September 2019 and range from 0 (least secretive) to 100 (most secretive). They are calculated as arithmetic averages of 20 key financial secrecy indicators (KFSIs) which are grouped around four broad dimensions of secrecy: (i) ownership registration (five indicators); (ii) legal entity transparency (five indicators); (iii) integrity of tax and financial regulation (six indicators); and (iv) international standards and cooperation (four indicators).

The secrecy scores methodology has evolved with subsequent editions of the FSI, in line with the evolving financial transparency standards. Most notably, the methodology has undergone substantial changes in its 2018 edition as compared to the 2015 edition introduced in academic literature by Cobham et al. (2015). To construct the BFSI in this paper, we use the 2020 edition, which has remained largely consistent with the 2018 version. A detailed description of the secrecy scores and each of their indicators (as well as the changes made over the subsequent editions) is provided by the Tax Justice Network (2015, 2018, 2020a).

The individual indicators are, for the most part, unilateral (i.e. they do not differ by partner jurisdiction). The only indicators which are bilateral in nature are KFSIs 18 (AIE), 19 (bilateral treaties), and 20 (international legal cooperation). We adjust these KFSIs specifically for intra-European relationships, where cooperation is more intensive than is portrayed by the original secrecy scores, resulting in corresponding lower secrecy levels among EU members. However, since most European countries had already scored low on these indicators, these adjustments have not had a substantial effect. We report both the original secrecy scores as well as their adjusted values in Table A9 in the Appendix. Despite their imperfections, we consider the secrecy scores of the FSI to constitute the best available indicators of financial secrecy, a point of view supported by both academic and policy debate (see e.g. Clark et al. 2015).

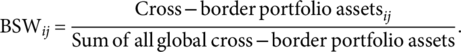

Second, in the quantitative part of the index, we replace unilateral global scale weights used in the FSI with bilateral scale weights (BSWs). Whereas the FSI used exports of financial services of each jurisdiction derived and partially extrapolated from multiple sources to calculate its share of the global total (Tax Justice Network 2020a), we replace this with bilaterally available portfolio investment data. We use data on cross-border portfolio assets from the International Monetary Fund (IMF)'s Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey (CPIS) for 6,623 bilateral relationships in 2018. While the use of either portfolio assets or liabilities is supported by certain arguments, as discussed by for example Cobham et al. (2015), we choose to use assets because of their better coverage and suitability to analyze the role of small secrecy jurisdictions which often do not directly report under CPIS, and would thus be missing as destinations for hiding assets.1

To construct the final BFSI value, we combine the BSWs (based on the value of assets held by residents of country i in secrecy jurisdiction j) with the secrecy score of jurisdiction j. Therefore, we estimate the BFSI only for countries which report data on the value of their citizen's portfolio assets in countries for which secrecy scores are available to the IMF CPIS. We use the best available data while keeping in mind their weaknesses. For example, the CPIS data include portfolio investment by households, but also by companies and banks, with the latter two likely dominating at least some of the bilateral relationships. Also, as the CPIS might not cover the whole scale of economic and investment activities relevant to financial secrecy, this might lead to imprecise results by omitting important activity. However, we argue that the CPIS is the best available data source for individuals' holdings of financial assets which we aim to capture in the BFSI.

Other data, such as that on foreign bank deposits, foreign direct investment (FDI), or trade, could be used to construct BSWs as well. The closest alternative to the CPIS is the Bank for International Settlements' (BIS) locational banking statistics (LBS). The LBS dataset includes data at the bilateral level for 31 reporting countries, including some notorious tax havens, and starts in early 2000s for most country pairs. However, this data has its own weaknesses: coverage is relatively low for our purposes, with some of the most important secrecy jurisdictions missing, and only includes bank deposits while simultaneously excluding the portfolio asset classes of equities, bonds, and mutual fund shares that households entrust to offshore banks (which, as ascertained by Zucman (2013), account only for approximately one quarter of offshore financial wealth). In addition, as Alstadsaeter et al. (2018) argue, the use of anonymous shell corporations makes it increasingly difficult to identify the beneficial owners of the wealth held offshore, an issue which also pertains to the CPIS data. Other alternative proxy variables for the strength of the economic relationship that might be relevant for financial secrecy are data on trade in services and FDI. As a form of robustness test, we construct the BFSI with BSWs based on foreign bank deposit data (from the BIS LBS), FDI (from the IMF's Coordinated Direct Investment Survey), and trade in financial services (from the World Trade Organization). In Table A1 in the Appendix we report that the correlation coefficients between the four different versions of BFSI that each use different data to estimate the BSW are high. In Table A2 in the Appendix, we provide descriptive statistics for the four variables as well as for the original and adjusted secrecy scores.

While multiple ways of combining the two components are relevant, we use the cube/cube-root formula to construct the BFSI in the same way as in the original FSI for two reasons. First, we aim to maintain methodological consistency to the greatest possible extent to ensure comparability with the FSI as a widely used and established measure of financial secrecy. Second, as confirmed in a statistical audit of the FSI methodology (Becker et al. 2016; Tax Justice Network 2018), the statistical properties of the distributions of the two variables are fundamentally different, thereby preventing the use of a simpler multiplicative formula.

3.2 BFSI results

In total, we estimate the BFSI for 82 countries which face secrecy supplied to them by up to 131 secrecy jurisdictions. As data on portfolio investment are not available for all country pairs, we estimate the BFSI for only 5,657 of the total of 82 * 131 = 10,742. We find that a relatively small number of relationships are responsible for a large share of the total global sum of BFSI values: the top 50 relationships are responsible for 9.61 percent of all global secrecy as measured by the BFSI. In Table A3 in the Appendix we provide a list of the 15 relationships with the highest BFSI values.

We illustrate the BFSI by presenting the data of the top 10 secrecy jurisdictions for Germany and the United States in Table A4 in the Appendix. We observe a substantial heterogeneity with respect to which secrecy jurisdictions are most important for the two countries: while for Germany, the Netherlands and Luxembourg are the most important suppliers of secrecy, and for the United States these are the Cayman Islands and Switzerland. In addition to estimating which secrecy jurisdictions are important for individual countries, the BFSI can also be used to analyze important secrecy jurisdictions for various groups of countries. For example, in Table 2 we explore the differences across groups of countries by per capita income (according to the World Bank's classification; since there is no data available to estimate the BSWs for any of the low-income countries, we only compare the remaining four income groups). Five jurisdictions are included among the top 10 jurisdictions for all four income groups – the United States (which tops the list for every income group), Hong Kong, the Netherlands, the Cayman Islands, and Switzerland. The United Arab Emirates is in the top 10 for three lower-income groups and thirteenth for OECD countries. These results show that these several major global financial centers are responsible for most of the secrecy faced by countries across all income levels.

| Rank | Lower middle income | BFSI | Upper middle income | BFSI | High income: non-OECD | BFSI | High income: OECD | BFSI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | United States | 667 | United States | 2,185 | United States | 3,852 | United States | 10,321 |

| 2 | United Arab Emirates | 395 | Cayman Islands | 1,461 | Cayman Islands | 3,644 | Cayman Islands | 9,411 |

| 3 | Netherlands | 372 | Switzerland | 1,022 | Switzerland | 2,188 | Netherlands | 7,236 |

| 4 | Cayman Islands | 298 | Hong Kong | 995 | United Arab Emirates | 1,772 | Switzerland | 6,831 |

| 5 | Hong Kong | 256 | Luxembourg | 920 | Bermuda | 1,703 | Luxembourg | 5,319 |

| 6 | China | 220 | British Virgin Islands | 872 | China | 1,661 | Japan | 5,162 |

| 7 | Switzerland | 219 | Bermuda | 849 | British Virgin Islands | 1,630 | Bermuda | 4,073 |

| 8 | Singapore | 212 | Singapore | 799 | Netherlands | 1,472 | Hong Kong | 3,543 |

| 9 | Thailand | 177 | Netherlands | 798 | Japan | 1,343 | Germany | 3,520 |

| 10 | Jordan | 175 | United Arab Emirates | 795 | Hong Kong | 1,286 | France | 3,465 |

- BFSI, Bilateral Financial Secrecy Index.

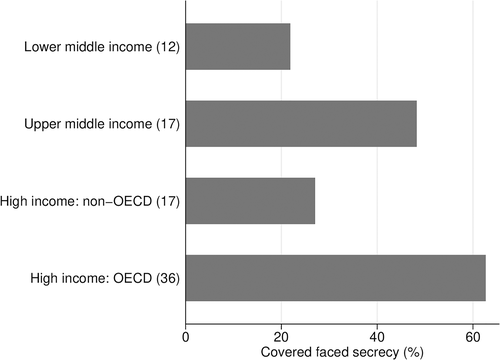

- Source: Authors.

We can reverse the analysis and look at countries and country groups that supply the most secrecy to other jurisdictions by summing up BFSI values for secrecy-supplying jurisdictions. By doing so, we essentially create a single ranking of jurisdictions in terms of how much secrecy they supply to other countries – an objective of the original FSI. The results of the summed BFSI and the original FSI are indeed quite similar, with a correlation coefficient of 0.892. It is thus no surprise that the same secrecy jurisdictions rank highest – the United States together with the Cayman Islands and Switzerland make up the top three in both rankings. In Table A5 in the Appendix we report the most important destinations for the secrecy supplied by these three jurisdictions.

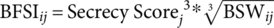

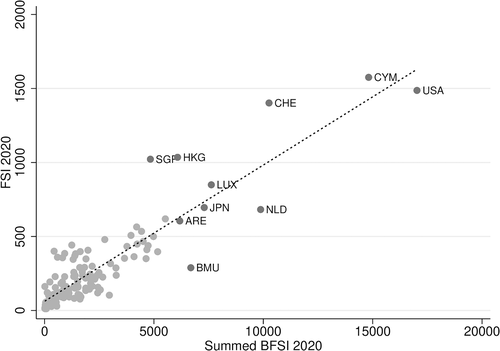

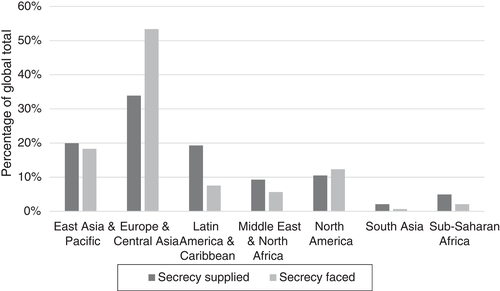

In Figure 1, we compare the shares of secrecy supplied and faced by each income group. In total, OECD countries face 67.7 percent of the global secrecy while only supplying 44 percent, with all of the remaining income groups supplying more secrecy than they face. Table A6 in the Appendix then shows these results in more detail in the form of a matrix of shares of secrecy supplied by income groups in columns to income groups in rows. We find that the bulk of the secrecy that OECD countries face from non-OECD countries is supplied by OECD's overseas countries and territories, primarily those associated with the United Kingdom. This finding supports the notion of prevailing hypocrisy in international tax governance, not only as regards the United States but of the entire OECD as a club of global rule setters which tolerates and seeks to benefit from secrecy business in its backyard.

Source: Authors.

We provide a similar breakdown by regional groups in Table A7 in the Appendix. We observe that some secrecy jurisdictions specialize in supplying secrecy to countries that are close to them geographically, such as Saudi Arabia to South Asia or Panama to Latin America. We again derive a matrix of shares of total global secrecy among regional groups (shown in Table A8 and Fig. A2 in the Appendix) and find that Europe and Central Asia supplies 33.9 percent and faces 53.4 percent of total global secrecy. We also find that Europe & Central Asia and North America are among the regions that face more secrecy than they supply, with jurisdictions in Latin America & the Caribbean being responsible for most of this difference.

Lastly, as a robustness check for our methodological choice to use data on portfolio assets to construct BSWs, we recalculate the original FSI using data on portfolio assets to calculate global scale weights. We again find similar results: the correlation coefficient between the summed BFSI and the FSI using CPIS data is 0.983; and between the original FSI and the FSI using CPIS data, it is 0.885. We report the results for individual jurisdictions of the summed BFSI as well as the original FSI and the FSI using CPIS data in Table A9 in the Appendix and we compare the summed BFSI with the original FSI in Figure A1 in the Appendix. We find that, among the most important secrecy jurisdictions, the two indices differ most for Bermuda and the Netherlands on the one hand (where the BFSI suggests that these are more important than is portrayed by the FSI), and Singapore, Hong Kong, and Switzerland on the other (where the BFSI suggests that these are less important than is portrayed by the FSI). This is roughly in line with the perceived role of Singapore, Hong Kong, and Switzerland as financial centers that export large amounts of financial services while not being proportionately important as portfolio investment destinations.

3.3 Research design for assessing AIE and blacklisting

We now describe how we use the BFSI to evaluate two recent policies aimed at curbing financial secrecy – AIE and the EU's blacklists. For AIE, we use bilateral data available on the OECD's Automatic Exchange Portal (OECD 2018), displaying all activated relationships between pairs of jurisdictions under the CRS. In most of our empirical analysis, we use data on relationships as of January 4, 2018. In addition, we support some of our findings by analyzing the development of these relationships over time. One drawback of the OECD AIE portal is that updates are made without clear timelines; therefore, our data sample is composed of snapshots in time which can be complemented by future analyses of the development of the AIE network over time.

Other conditions notwithstanding, an exchange relationship is activated whenever two jurisdictions either conclude a bilateral competent authority agreement or list each other under the multilateral competent authority agreement (MCAA) in its Annex E (Meinzer 2018). However, Annex E is not made public. This prevents us from directly observing countries' preferences for activating – or not – exchanges with any given jurisdiction. Therefore, only pairs of countries which have chosen each other in Annex E or have otherwise concluded a bilateral agreement can be observed. A further complicating factor is the absence of harmonized deadlines for the submission of countries' exchange preferences and the fact that many jurisdictions have committed to exchange only in 2018 or even later (OECD 2017).

Multilateral agreements suffer from three complicating factors. The first involves the possibility of jurisdictions voluntarily choosing only to send, but not receive, tax information; to do so, these jurisdictions enlist in Annex A of the MCAA. Moreover, banks in other jurisdictions are not required to report accounts held by residents of Annex A countries. This tactic enables secrecy jurisdictions to attempt luring foreign residents into taking up fake residency or citizenship, resulting in bank accounts falsely being classified as belonging to an Annex A jurisdiction resident. Information on these accounts' owners is then neither collected nor exchanged (Tax Justice Network 2018, pp. 97–104, 133–40). The second problem involves the data protection assessments that the OECD is currently performing on entrants to the AIE mechanism, the outcomes of which remain confidential. When the OECD diagnoses weaknesses in data protection, the jurisdiction in question is not eligible to receive any data under competent authority agreements. The third complicating factor associated with multilateral agreements involves the EU directive on AIE (Council of the European Union 2014), which does not provide for nonreciprocal information exchanges and which overrides any EU member's preference as expressed in Annex A, and which might also override the data protection assessments of the OECD. In addition to agreements among EU member states, specific treaties between the EU as a whole and six non-EU members are in place, which very likely only allow for reciprocal exchanges. The countries concerned are Switzerland, Liechtenstein, San Marino, Andorra, Monaco, and Saint-Barthelemy (European Commission 2017a). As a result, the data allows us to observe that some jurisdictions (Cyprus, Romania) are exchanging information reciprocally with the EU and a handful of third countries covered by EU-equivalent treaties but not with the rest of the world. Although it is impossible for us to know for sure why this is the case, it is likely that data protection concerns explain Romania's exclusion while Annex A might explain Cyprus' asymmetry.

Furthermore, the United States is absent from the OECD data we use in this paper as it does not participate in AIE under the CRS. We apply this fact consistently throughout this paper, that is we observe the United States as having 0 percent of its supplied financial secrecy covered by AIE. However, due to the application of FATCA, the United States does receive comparable information from almost every country in the world (though it does not share similar data with its partners). If we were to extend our definitions and data sources to cover both AIE and, in the special case of the United States, FATCA, this might be beneficial for the BFSI as a general risk assessment tool, from which the United States would emerge as a country which is in fact very successful in obtaining information from other countries. While we prefer to rely on CRS only for the sake of consistency, the special case of the United States should be kept in mind when interpreting the results.

The last group of data we use in our empirical analysis are lists of noncooperative jurisdictions published by the EU. On December 5, 2017, after years of political pressures and negotiations, the European Commission published the first version of lists of noncooperative jurisdictions (European Commission 2017b). The lists are the outcome of a screening process which has covered 92 jurisdictions. Seventy-two of these were asked to address deficiencies, and 47 of them committed to “improve transparency, stop harmful tax practices, introduce substance requirements, or implement OECD BEPS” (European Commission 2017b), and were subsequently placed on a grey list. Eight countries were given more time to address the deficiencies as they had recently been hit by natural disasters while the remaining 17 jurisdictions were blacklisted as noncooperative. Since then, the European Commission has updated the list many times – see European Commission (2020) for details – as jurisdictions gradually implement (or not) the required measures. In our analysis, we use three versions of the lists – the initial December 2017 list and its December 2018 and November 2019 updates – to assess how well they align with BFSI results.

An important caveat to consider in this part of the analysis is that the secrecy scores themselves include an indicator on AIE – KFSI 18 (KFSI-18; see Tax Justice Network 2020a, 2020b, 2020c, 2020d). Since the final secrecy score of a jurisdiction is calculated as the arithmetic average of 20 KFSIs, for the purposes of this part of the analysis we derive an alternative set of secrecy scores which exclude KFSI-18 and are constructed as arithmetic averages of the remaining 19 KFSIs. We do this to prevent the potential endogeneity of secrecy scores when assessing the relationship between measures of secrecy and the ratio of supplied and faced secrecy covered by AIE. We report these adjusted secrecy scores for each jurisdiction in Table A9 in the Appendix.

(1)

(1)Second, we test whether countries, in their efforts to counter the negative effects of secrecy, conclude bilateral AIE agreements with their most important suppliers of secrecy. In this part of the analysis, we thus focus on countries that face secrecy (rather than those that supply it). We hypothesize that richer and more powerful countries are better than other countries at covering their most relevant secrecy jurisdictions with AIE. We test the hypothesis using the model specified in Equation (1) where we replace the dependent variable by the share of faced secrecy that country i has managed to cover by active AIE relationships.

4 Results

We begin with the supply side of financial secrecy and investigate whether or not more secretive jurisdictions manage to keep more of the secrecy they supply to other countries uncovered by AIE. We then turn to the receiving end of financial secrecy and test whether OECD countries are better than other countries at covering and coercing their most relevant secrecy jurisdictions using AIE. Finally, we use the BFSI to evaluate whether EU member states are better at targeting their most relevant secrecy jurisdictions with AIE or with blacklisting.

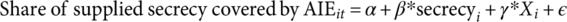

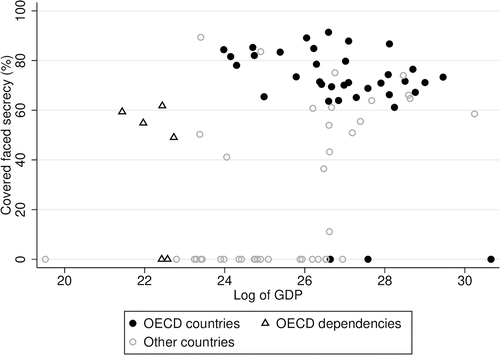

4.1 Secrecy jurisdictions successfully resisting coercion?

We hypothesize that secrecy jurisdictions purposefully refrain from activating AIE relationships with countries to which they supply secrecy. Hong Kong is a clear example of a secrecy jurisdiction which supplies substantial secrecy to other countries and which has been very slow in activating AIE relationships. Within the EU, in Figure A3 in the Appendix we observe that three EU member states have a particularly low number of activated AIE relationships – Cyprus, Romania, and Bulgaria. The relationship between the share of supplied secrecy covered by active AIE treaties and the secrecy score is shown in Figure 2. We observe that countries which have engaged in at least one AIE relationship exhibit a negative correlation between the share of supplied secrecy covered by active AIE and the secrecy score. This suggests that more secretive jurisdictions are less likely to activate AIE relationships, or at least are more likely to postpone activating these relationships, with countries to which they supply secrecy. The relationship is partly driven by highly secretive OECD dependencies which have thus far covered only relatively low shares of the secrecy they supply to other countries, although there are many other jurisdictions with high secrecy scores in similar positions. OECD countries, on the other hand, are among those that have covered most of the secrecy they supply to other countries.

Source: Authors.

In addition to this trend, a cluster of jurisdictions found in the bottom right corner of Figure 2 exhibit high secrecy scores and, at the same time, have not yet disclosed any AIE exchange partners.2 We recognize three possible explanations for the position of these countries. First, these jurisdictions aim to gain from their secrecy by attracting wealth from abroad, and so far they have been successful in avoiding the activation of any AIE relationships (either by delaying the activation of the signed treaties or by not signing any treaties). For the majority of these countries, Figure 2 provides evidence consistent with this explanation. Second, these jurisdictions' foreign activities may be very small and it is thus not on their policymakers' agendas to negotiate AIE treaties at all. Third, if the jurisdiction's foreign activities are indeed very small, it may be the case that it is not on the agenda of policymakers of other countries to activate AIE relationships with these jurisdictions. A fourth explanation is theoretically possible as well, that is that some of these countries have activated some AIE relationships, but no data is currently available on portfolio assets between these countries, which is why the share of covered supplied secrecy would be zero. However, no such case has been empirically observed.

More formally, Table 3 presents the results of the estimation of the regression models characterized by Equation (1). We find that there is a negative and statistically significant relationship between the secrecy score and the share of supplied secrecy covered by active AIE, including when controlling for income and regional effects. The results suggest that an increase of 1 point in the secrecy score is associated with a roughly 0.7 (0.36 when controlling for regional and income effects) percentage point lower share of BFSI covered by active AIE treaties. Our findings thus suggest that high-secrecy jurisdictions are aware of which countries they supply their secrecy to, and have so far been successful in avoiding or delaying the activation of AIE relationships with these countries, engaging in a strategy of selective resistance.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secrecy Score 2020 (adjusted) | −0.703*** (0.149) |

−0.362* (0.196) |

−0.72*** (0.155) |

−0.36* (0.197) |

||||

| Global Scale Weight 2020 | −53.35 (57.29) |

−82.9 (52.43) |

−15.29 (60.87) |

−83.47 (50.72) |

||||

| Financial Secrecy Index 2020 (adjusted) | −0.008 (0.007) |

−0.007 (0.006) |

||||||

| Regional groups | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Income groups | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| No. of observations | 78 | 78 | 78 | 78 | 78 | 78 | 78 | 78 |

| R2 | 0.22 | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.37 | 0 | 0.34 | 0.03 | 0.34 |

- Notes: Robust standard errors in parentheses. ***P < 0.01, **P < 0.05, *P < 0.1. Secrecy scores (and, consequently, the Financial Secrecy Index) are adjusted for intra-EU relationships and exclude Key Financial Secrecy Indicator 18 on AIE (see Section 4).

- Source: Authors.

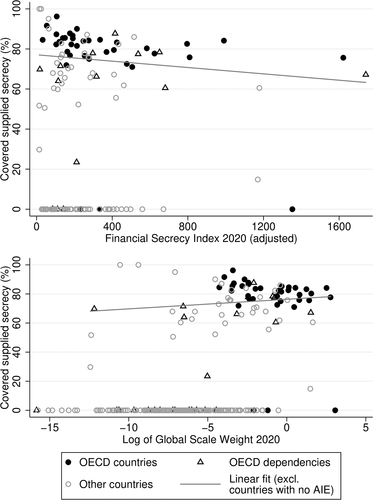

To further examine the relationship and to provide more insight into which secrecy jurisdictions manage to avoid AIE in part or entirely, we run the regressions with the explanatory variables being the FSI value and the global scale weights instead of as well as in addition to the secrecy scores. In doing so, we assess whether the negative relationship found above is driven by secrecy, by the scale of cross-border activity, or both. We present the results in columns 3–8 in Table 3 and we show the relationship graphically in Figure A4 in the Appendix for the FSI value (top panel) and the global scale weights (bottom panel). While the coefficients are negative, we do not find statistically significant evidence for the hypothesis that the FSI value and the global scale weights are associated with a lower share of supplied BFSI covered by AIE treaties. These results suggest that secrecy scores are more important indicators of a tendency of jurisdictions to delay the activation of important AIE relationships than the scale of the jurisdictions' cross-border financial activity.

Overall, we find that jurisdictions with high secrecy scores manage to keep more of the secrecy they supply to other countries uncovered by AIE and that they engage in selective resistance. Our results thus indicate that AIE is highly important to secrecy jurisdictions, and that future policy efforts should stress the development of AIE relationships with the most secretive jurisdictions and the need for true multilateralism as opposed to allowing for bilateral cherry-picking. Our findings further suggest that OECD-controlled secrecy jurisdictions do not necessarily succeed in dodging relevant exchange relationships more successfully than non-OECD dependent secrecy jurisdictions. However, we observe that OECD dependencies prevent a far higher share of their secrecy risks from being covered by AIE than OECD members themselves. This lends support to the notion of OECD hypocrisy in outsourcing secrecy business to its dependencies, and to the hypothesis of a sham standard (see Table 1) designed by the OECD which secures secrecy business for these dependencies while the OECD members themselves accept higher transparency.

4.2 AIE: Powerful countries successfully coercing secrecy jurisdictions?

Next, we focus on faced secrecy and to what extent countries are capable of covering the secrecy they face with AIE. In other words, we test whether countries, in their efforts to counter the negative effects of the secrecy they face, conclude bilateral AIE agreements with their most important secrecy suppliers. Figure A3 in the Appendix shows the share of BFSI accounted for by countries which are covered by existing activated AIE treaties versus the number of AIE relationships set up with these jurisdictions (as of four dates between January 2018 and October 2019). We observe substantial heterogeneity in countries' success in activating AIE relationships with their specific most important secrecy jurisdictions: while some countries, such as New Zealand, Poland, or Greece, had already by January 2018 covered around 90 percent of the secrecy they faced, other countries have covered much less despite having activated similar numbers of AIE relationships.

This straightforward comparison between the share of faced secrecy covered by AIE and the number of active AIE relationships can help us identify cases in which the policymakers' attention and resources with respect to AIE might not be directed to the jurisdictions which harm their countries the most. For example, as of January 2018 Malaysia had activated 73 AIE relationships but only covered 53.9 percent of the secrecy it faced; strikingly, Malaysia did not have an AIE relationship with five of its top six largest secrecy suppliers. In contrast, New Zealand had also activated 73 AIE relationships, but covered 89.1 percent of the secrecy it faced. China, Brazil, Argentina, and Colombia were in similar situations as Malaysia. While the network of AIE relationships has improved substantially between January 2018 and October 2019 and most countries now cover most of the secrecy they face, we argue that the BFSI can help guide the focus of future policies as they are being implemented.

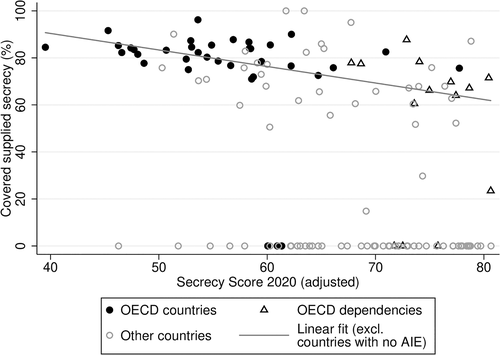

In agreement with our discussion in Section 2, we expect that more powerful countries would be better than others at targeting their most relevant secrecy jurisdictions with AIE. The one group of more powerful countries in tax matters is the OECD, whose members enjoy privileges associated with decisionmaking in international tax matters and standard setting. Figure 3 shows the share of covered faced secrecy by income group. On average, high-income OECD member states successfully cover substantially more of the secrecy they face than any other income group (above 60 percent vs. between 20 and 50 percent).3 Overall, we conclude that powerful (OECD member) countries cover their most relevant secrecy jurisdictions with AIE more successfully than others. In the typology of tax standards from Table 1, this finding lends support to AIE being a club standard primarily imposed for the club members' benefit.

Source: Authors.

4.3 EU's lists of noncooperative jurisdictions

Finally, we turn to examining and comparing the EU's blacklisting approach with its external AIE network. Using the BFSI, we find that 30.1 percent of the secrecy faced by EU countries is supplied by other member states (most importantly by the Netherlands and Luxembourg).4 With respect to secrecy jurisdictions outside the EU, Table 4 shows the top 15 suppliers of secrecy to the EU member states along with an indication of whether the jurisdiction was included on the black or the grey list published by the European Commission. Out of the 17 blacklisted jurisdictions on the original blacklist from December 2017, only 12 have secrecy scores available, and these are together responsible for only 5.9 percent of the BFSI faced by the EU member states. Comparing the results of the BFSI with the grey list, we find that the original list, which included 47 jurisdictions (of which we have secrecy scores for only 25), covered 26.9 percent of secrecy faced by the EU. The black and grey lists from December 2018 covered 0.3 percent and 33.6 percent of faced secrecy, while those from December 2019 covered 0.35 percent and 15.9 percent, respectively. We find that 10 of the top 15 BFSI jurisdictions that supply secrecy to the EU have at least at one point been included on the lists (i.e. they have been identified by the European Commission as in need of addressing deficiencies), with the United States, Japan, Canada, Singapore, and China missing.5 The United Arab Emirates and South Korea have moved from the black list to the grey list only in the January 2018 update. Overall, while the EU has, to a large extent, succeeded in identifying the most potentially harmful jurisdictions according to the BFSI, as of December 2019 only four of these remain on the grey list, and none are on the black list.

| Rank | Country | BFSI | Secrecy Score | Lists of noncooperative jurisdictions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017/2012 | 2018/2012 | 2019/2012 | ||||

| 1 | United States | 6,515 | 63 | |||

| 2 | Cayman Islands | 4,954 | 76 | |||

| 3 | Switzerland | 4,289 | 74 | |||

| 4 | Japan | 3,041 | 63 | |||

| 5 | Bermuda | 2,344 | 73 | |||

| 6 | Jersey | 2,238 | 66 | |||

| 7 | Guernsey | 2,082 | 71 | |||

| 8 | Hong Kong | 2,020 | 66 | |||

| 9 | United Arab Emirates | 2,009 | 78 | |||

| 10 | Canada | 1,987 | 56 | |||

| 11 | British Virgin Islands | 1,973 | 71 | |||

| 12 | Singapore | 1,691 | 65 | |||

| 13 | South Korea | 1,638 | 62 | |||

| 14 | China | 1,571 | 60 | |||

| 15 | Thailand | 1,517 | 73 | |||

- Source: Authors.

- Note: The editions of the black and grey lists for the years 2017–2019 are those that were effective in December of each year and published on December 5, 2017, December 4, 2018, and November 14, 2019, respectively.

When comparing the success of the EU's lists of noncooperative jurisdictions with the EU's AIE network in targeting faced secrecy, our expectation, as discussed in Section 2, is that AIE would be more successful than blacklisting. To enable such a comparison, we must take into consideration that the EU's blacklists omit other EU member states by design. After adjusting the faced secrecy risks by removing any supply of secrecy from within the EU, we find that the EU member states' AIE network has thus far covered 58.7 percent of the secrecy supplied to them. In contrast, the blacklisting exercise has covered between 15.9% and 33.6 percent. We thus conclude that the EU member states are indeed more successful in targeting their most relevant secrecy jurisdictions with AIE rather than with blacklisting.

5 Conclusion

In this paper we address the question of how successful countries are in targeting secrecy jurisdictions with their policies. To that objective, we develop the BFSI and use it to evaluate two recent policy initiatives: AIE and the blacklisting of noncooperative jurisdictions. We thus contribute to solving a pressing dilemma in international tax governance: how to reconcile the apparent simultaneity of successful international tax cooperation and continued resistance by secrecy jurisdictions. While we point out various loopholes in the AIE policy framework (i.e. CRS), our key findings rest on the assumption that the AIE system reduces financial secrecy and associated risks for illicit financial flows. In the policy era of AIE as designed by the OECD, we find evidence that particularly secretive jurisdictions successfully can and do apply a strategy of selective resistance in dodging relevant information exchange relationships. We interpret our results as in support of the hypothesis of a hypocrisy on the part of OECD countries, in that their controlled secrecy jurisdictions – above all those of the former colonial powers, i.e. the UK and the Netherlands – are found to be using selective resistance far more intensely than OECD member states. This complements earlier findings of US hypocrisy in international tax governance (Hakelberg & Schaub 2018) and supports the notion of AIE under CRS being a sham standard.

Our second main finding shows that countries belonging to the OECD, the most powerful club of countries in the tax world, are more successful than others in targeting their most relevant secrecy jurisdictions with AIE. Thus, under the cherry-picking system, they seem to be better able to target and coerce their secrecy suppliers into cooperation than nonmembers. This observation lends support to the AIE system being a club standard that benefits primarily OECD members.

Third, we find that the EU's blacklisting exercise of the European Commission, when compared to AIE, has been less successful at targeting the secrecy that EU member states face. Despite AIE relationships requiring bilateral consent between two partners (and blacklisting not requiring such consent between the listing and the listed), the share of EU's faced secrecy covered by AIE is more than twice as high as that covered by the lists. This finding supports our critical discussion of blacklisting as the basis for both policymaking and academic research. We suggest that future research on secrecy jurisdictions and the policy to counter them replace those lists with more nuanced, continuous, nonpolitical and objectively verifiable measures, such as secrecy scores or the BFSI.

While international political economy scholars have previously found AIE to be successful in rolling back neoliberalism, we are more cautious about its ultimate effectiveness and underline the urgent need for detailed statistics on the CRS to ensure public accountability and further probing research. Until such data becomes available, the dyadic secrecy risk approach presented in this paper poses additional questions and opens avenues for further research: how would the findings of selective resistance, OECD power and hypocrisy change if the US FATCA were included in the analysis? While FATCA is highly asymmetrical even in its reciprocal version, there are many countries that do not obtain any reciprocity from the United States. In addition, we suggest that the typology of international tax cooperation comprises a fruitful framework of analysis for bringing power back into the scholarly debate on international tax governance, which could be tested e.g. with the use of a gravity model. The framework also facilitates a systematic analysis of the relationship between countries at various levels of income per capita, including patterns and histories of colonial exploitation.

Acknowledgments

This research has been supported by the European Union's Horizon 2020 program through the COFFERS project (No. 727145). Petr Janský and Miroslav Palanský also acknowledge support from the Grant Agency of the Czech Republic (P403/18- 21011S) and Miroslav Palanský also acknowledges support from the Charles University Grant Agency (848517). The authors are grateful to Alex Cobham, Lukas Hakelberg, Thomas Rixen, Moran Harari, Andres Knobel, Anastasia Nesvetailova, Leonard Seabrooke, Alain Trannoy, anonymous referees, and seminar participants at Charles University, the Tax Justice Network Conference, the Annual Congress of the International Institute of Public Finance, the European Consortium for Political Research conference, and the Journées LAGV18 conference for useful comments. Data, code, and full results can be accessed at the Open Science Foundation website: https://osf.io/kmcyv

Endnotes

Appendix

Source: Authors.

Source: Authors.

Source: Authors.

Source: Authors.

Source: Authors.

| BFSI (portfolio assets) | BFSI (bank deposits) | BFSI (trade in financial services) | BFSI (foreign direct investment) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BFSI (portfolio assets) | 1 | |||

| (6,743) | ||||

| BFSI (bank deposits) | 0.7908*** | 1 | ||

| (3,860) | (7,438) | |||

| BFSI (trade in financial services) | 0.8255*** | 0.8156*** | 1 | |

| (536) | (459) | (558) | ||

| BFSI (foreign direct investment) | 0.7359*** | 0.7433*** | 0.8171*** | 1 |

| (3,387) | (2,498) | (470) | (4,482) |

- Note: Number of observations in parentheses.

- Source: Authors.

- *P < 0.1; **P < 0.05; ***P < 0.01.

| Variable | Obs. | Mean | Standard deviation | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPIS assets (US$ million) | 12,924 | 3,990 | 42,800 | 0 | 1,690,000 |

| Bank deposits (US$ million) | 4,907 | 4,140 | 30,800 | 0 | 969,000 |

| Exports of financial services (US$ million) | 526 | 151.2 | 649.2 | 0 | 8,928 |

| Foreign direct investment (US$ million) | 5,314 | 6,310 | 42,800 | 0 | 959,000 |

| Secrecy Score | 133 | 63.9 | 10.2 | 37.6 | 79.8 |

| Secrecy Score (adjusted for intra-EU relationships) | 133 | 63.8 | 10.2 | 37.6 | 79.8 |

| Secrecy Score (adjusted for intra-EU relationships and excluding KFSI 18) | 133 | 65.4 | 9.9 | 39.5 | 80.7 |

- Source: Authors.

| Supplier of secrecy | Country facing the secrecy | Secrecy score of secrecy supplier | Bilateral scale weight | BFSI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cayman Islands | United States | 76 | 3.3% | 1,408 |

| Cayman Islands | Japan | 76 | 1.7% | 1,132 |

| Cayman Islands | Hong Kong | 76 | 0.9% | 923 |

| Switzerland | United States | 74 | 0.9% | 859 |

| United States | Cayman Islands | 63 | 3.2% | 788 |

| United States | Japan | 63 | 2.9% | 767 |

| United States | Luxembourg | 63 | 2.1% | 687 |

| United States | United Kingdom | 63 | 2.0% | 676 |

| Japan | United States | 63 | 1.9% | 668 |

| United States | Canada | 63 | 1.9% | 665 |

| United States | Ireland | 63 | 1.9% | 658 |

| Bermuda | United States | 73 | 0.5% | 642 |

| Netherlands | United States | 67 | 0.9% | 640 |

| Cayman Islands | Luxembourg | 76 | 0.2% | 595 |

| Bermuda | Hong Kong | 73 | 0.3% | 529 |

- Source: Authors.

| Rank | Germany | SS | BSW | BFSI | United States | SS | BSW | BFSI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Netherlands | 67 | 0.5% | 505 | Cayman Islands | 76 | 3.3% | 1,408 |

| 2 | United States | 63 | 0.8% | 487 | Switzerland | 74 | 0.9% | 859 |

| 3 | Switzerland | 74 | 0.1% | 410 | Japan | 63 | 1.9% | 668 |

| 4 | Luxembourg | 55 | 1.2% | 377 | Bermuda | 73 | 0.5% | 642 |

| 5 | Cayman Islands | 76 | 0.0% | 330 | Netherlands | 67 | 0.9% | 640 |

| 6 | France | 50 | 0.8% | 236 | Canada | 56 | 1.9% | 464 |

| 7 | Japan | 63 | 0.1% | 214 | Hong Kong | 66 | 0.3% | 431 |

| 8 | Austria | 57 | 0.2% | 202 | Taiwan | 66 | 0.3% | 408 |

| 9 | United Arab Emirates | 78 | 0.0% | 192 | Curacao | 75 | 0.1% | 406 |

| 10 | Canada | 56 | 0.1% | 184 | British Virgin Islands | 71 | 0.1% | 387 |

- Notes: Secrecy scores (SS) from the Financial Secrecy Index 2020. BSW stands for bilateral scale weights.

- Source: Authors.

| Rank | United States | BFSI | Cayman Islands | BFSI | Switzerland | BFSI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cayman Islands | 788 | United States | 1,408 | United States | 859 |

| 2 | Japan | 767 | Japan | 1,132 | Luxembourg | 473 |

| 3 | Luxembourg | 687 | Hong Kong | 923 | United Kingdom | 419 |

| 4 | United Kingdom | 676 | Luxembourg | 595 | Germany | 410 |

| 5 | Canada | 665 | Ireland | 502 | Norway | 361 |

| 6 | Ireland | 658 | United Kingdom | 492 | Ireland | 356 |

| 7 | Netherlands | 528 | Switzerland | 472 | Japan | 347 |

| 8 | Norway | 491 | Netherlands | 426 | Canada | 337 |

| 9 | Germany | 487 | China | 414 | France | 329 |

| 10 | Bermuda | 469 | Australia | 406 | Netherlands | 314 |

- BFSI, Bilateral Financial Secrecy Index.

- Source: Authors.

| Income group | High: OECD | High: non-OECD | Upper middle | Lower middle | Low | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High: OECD | 31.0% | 19.4% | 0.7% | 5.8% | 10.9% | 67.7% |

| High: non-OECD | 7.9% | 6.9% | 0.1% | 1.6% | 3.3% | 19.8% |

| Upper middle | 4.2% | 3.7% | 0.1% | 0.8% | 1.4% | 10.2% |

| Lower middle | 1.0% | 0.7% | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.4% | 2.2% |

| Low | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Total | 44.0% | 30.8% | 0.8% | 8.3% | 16.1% | 100.0% |

- Source: Authors.

| Rank | East Asia and Pacific | Europe and Central Asia | Latin America and Caribbean | Middle East and North Africa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cayman Islands | USA | USA | USA |

| 2 | USA | Cayman Islands | Switzerland | Caymans |

| 3 | Bermuda | Netherlands | Cayman Islands | United Arab Emirates |

| 4 | British Virgin Islands | Switzerland | Netherlands | Qatar |

| 5 | Hong Kong | Luxembourg | Luxembourg | Switzerland |

| 6 | Switzerland | Japan | Japan | Jordan |

| 7 | China | Bermuda | Bermuda | Netherlands |

| 8 | Netherlands | Germany | Panama | Japan |

| 9 | Singapore | France | British Virgin Islands | Egypt |

| 10 | United Arab Emirates | Jersey | Canada | Hong Kong |

| Rank | North America | South Asia | Sub-Saharan Africa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cayman Islands | USA | USA | |

| 2 | Switzerland | United Arab Emirates | Switzerland | |

| 3 | USA | Saudi Arabia | Bermuda | |

| 4 | Japan | China | Cayman Islands | |