Professional action in global wealth chains

Abstract

This article provides a framework for explaining professional action in multi-jurisdictional tax and finance environments, focusing on how relationships between clients, professionals, and regulators shape market structures. Given the complexity of tax and financial regulations within and across national systems, professionals experienced in accounting, financial, legal, and policy systems have opportunities to engage to increase information asymmetries rather than lower them. This article draws on the recent literature on Global Wealth Chains to theorize how professionals develop action profiles to exploit opportunity structures through information gaps. We develop a theoretical framework for understanding how professionals may intentionally, and as a matter of strategy, exploit information gaps in different socio-economic contexts. We provide case vignettes of client-professional-regulator relationships in multi-jurisdictional tax and finance management, highlighting how professional action shapes wealth chains and attempts at regulatory intervention. Our theoretical contribution is to link micro-level interactions to macro-level structures of wealth creation and protection in the transnational economic and legal order.

1 Introduction

The coordination of international financial and tax governance is a complex affair. Not only do regulators require information on transactions between parties in their own economy but also across multiple jurisdictions. Such complexity provides ample opportunities for professionals experienced in accounting, financial, legal, and regulatory systems to exploit legal distinctions and information asymmetries between different authorities to exercise power in the formulation of, and adaptation to, regulations. If permitted, professionals can act as intermediaries between multinational corporations (MNCs) or wealthy elites and authorities (Abbott et al. 2017). They can control private information (c.f. Kruck 2017) and enable their clients to avoid unfavorable aspects of national tax and financial regulation (Rixen 2013; Riles 2014). While formal international financial and tax governance emerges from negotiated outcomes between public authorities (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs 2011; Genschel & Rixen 2015; Hakelberg & Schaub 2017), de facto governance of these matters is driven by how transnational professional communities interpret these rules (Christensen 2020). It is both the formal rules and the informal practices that determine political economy outcomes (Cooper & Robson 2006; Kentikelenis & Seabrooke 2017). This also means that professional action is often endogenous to regulatory processes. What we understand as “regulatory capture” is not only from external lobbying but also the established intellectual frameworks and professional practices that shape policy (Tsingou 2015; Slayton & Clark-Ginsberg 2018).

Recent public pressure on corporate and elite tax avoidance has led to some disquiet in the professional communities dealing with multi-jurisdictional tax and finance management, which seek to re-legitimate control over their professional activities and avoid arduous regulations (Radcliffe et al. 2018; Christensen 2020). For scholars of regulation and governance, such a moment compels us to improve our theorization and classification of what drives such professional action, and how micro-level interactions are linked to macro-level market structures. This article develops a theoretical framework to investigate how professionals act to exploit information gaps in the pursuit of wealth creation and protection across multiple jurisdictions.

We suggest that professionals develop “action profiles” to shape the development, implementation, and interpretation of formal legislation and accepted practices (Martin 2009). Professionals produce action profiles in relation to clients and to regulators, which reflect their intentions in working toward common aims, the extent of reciprocity, or if their goals are different. Identity maintenance among professionals (a “Big Four accountant,” a “tax lawyer,” etc.) is important in giving predictability to action profiles concerning likely tactics and strategies (White 2008; Spence & Carter 2014). Repertoires for action are maintained within these profiles, providing structure to relations (Martin 2011, p. 332). Relationships between clients, professionals, and regulators define what information is accessible, what constitutes relevant knowledge, and what can be done within finance and taxation systems (Thiemann & Lepoutre 2017).

Professional action also underpins the “regulatory arbitrage” that has been investigated in multiple regulatory contexts (Houston et al. 2012). Professionals' use of regulatory arbitrage is responsible for the exploitation of tax and accounting systems (Ahrens et al. 2022; Friedrich 2021), and the rise of shadow banking and financial vulnerabilities (Rixen 2013; Thiemann 2014a; Helgadóttir 2016), leading to calls for special resolution regimes in international finance (Ringe 2016; Marjosola 2021). Such arbitrage opportunities occur not only between firms and regulators, but also in the context of avoiding scrutiny from activist groups (Rao et al. 2011).

For multi-jurisdictional tax and finance management the professionals involved are often lawyers, accountants, financiers, or combinations thereof. Those who identify themselves as operating beyond the confines of any one national regulatory system may direct their own practices at some distance from national standards (Harrington & Seabrooke 2020) or implement them selectively (Thiemann 2014a,b). Such actors may also act as “double agents” in representing transnational interests while also playing off their embeddedness in domestic institutions (Dezalay & Garth 2016). Professionals can spur action by creating ties to other like-minded parties and through the creation of practices that are opaque to outsiders (Christensen & Skærbæk 2010). These characteristics permit professionals to draw from different pools of professional knowledge to exploit information asymmetries (Seabrooke 2014). We suggest such identities provide an important resource for locating types of interactions between professionals, clients, and regulators.

To detail the opportunity structures in which professionals act we draw on the recent literature on Global Wealth Chains (hereafter “wealth chains”; see Seabrooke & Wigan 2017; Sharman 2017; Finér & Ylönen 2017), which offers an overview of the socio-economic contexts in which professionals engage in both the formulation of, and adaptation to, new regulatory innovations. In the context of increased scrutiny and rapid change in international financial and tax governance (Christensen & Hearson 2019), we highlight how professionals may strategically exploit information asymmetries to shape the context and content of fiscal regulatory regimes. These regimes are fundamentally shaped by professional action, including the likelihood of regulatory failure and the distribution outcomes from tax avoidance and evasion.

To reveal the dynamics of professional action across multi-jurisdictional tax and finance environments, we need to differentiate what types of action profiles are common in the exploitation of information asymmetries. This is required for two reasons. First, by linking the interplay of micro-level professional practices and the institutional, social, and economic contexts in which multi-level regulation emerges, we can identify key sources of action. We do so by locating professional action in a typology of market structures. The wealth chains framework identifies five types of market structures – Market, Modular, Relational, Captive, and Hierarchy – in which asymmetries in regulation and information differ between clients, professionals, and regulators (Seabrooke & Wigan 2017). The wealth chains framework calls for research on how “wealth chains are maintained through professional and social networks” (Seabrooke & Wigan 2017, p. 4), and how information is codified through knowledge management in corporate and professional organizations (Morris 2001; Suddaby & Greenwood 2001). Here we develop a conception of how professionals relate with clients and regulators in coordinating and maintaining wealth chains. With this as context we provide a theory of how relations between clients, professionals, and regulators lead to action profiles in support of wealth chain types. In short, we posit that relations between these three parties center on information asymmetries between them, which drive wealth chains and their prospects for re-regulation. This framework allows us to link an analysis of micro-level interactions of professionals to macro-level institutions that support the distribution of capital across borders.

The second reason to locate sources of professional action is to understand what social systems support the practices of wrongdoing and misconduct that have led to the corporate and elite tax avoidance scandals of recent years (Gabbioneta et al. 2019; Christensen & Seabrooke 2020). This can be investigated in three ways. The first is as discrete acts in which professionals choose to gain a benefit in light of the risks posed in doing so. The second is that professional actions build upon a power structure in which benefitting from the wrongdoing of others is naturalized or unquestioned (Goodin & Pasternak 2016). The third is to view professional action through a “conflict of laws” approach (Riles 2014), which places emphasis on overlaps and conflicts between sovereigns claiming legal jurisdiction over an activity. All three types are important for professional action profiles in wealth chains: as discrete actions to “get away with it”; as choices made knowing that the system is weighed in your favor; or as contests over what is permissible across jurisdictions. These three types are supported by the current transnational economic and legal order.

Our key contribution is to provide theoretical reasoning that links micro-level professional interactions with clients and regulators to macro-level wealth chain outcomes. Market variations are the product of relations between professionals, clients, and regulators, and these relations rely on action profiles that guide the interpretation of rules and practices. Theorizing these relations is important in explaining why regulators' attempts to intervene between clients and professionals often fail, as well as locating how professional practices that support tax avoidance and evasion are sustained. Our aim is both analytical and normative, and realizing this ambition requires the following steps: first, we provide a brief summary of the wealth chains framework; second, we provide theoretical reasoning for likely forms of professional action in wealth chains; third, we provide three case vignettes where this reasoning is shown, discussing transfer pricing in MNCs, dividend fraud systems, and Advanced Business Services (ABSs) for high-net worth individuals (HNWIs). We conclude by establishing theoretical propositions linking micro-level professional actions to macro-level structures for scholarship on regulation and governance. This final step is important for building a conceptual framework for actual and likely relations between professionals, clients, and regulators in how they respond to market transformation and regulatory interventions.

2 Global wealth chains

The emerging literature on wealth chains takes its departure from the well-established work on Global Value Chains (hereafter "value chains"), a framework focused on transaction costs and lowering information asymmetries to generate economic development (Gereffi et al. 2005). The value chains approach has become firmly established with intergovernmental organizations like the World Bank and the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Value chains are delineated according to their complexity, the ability to codify information, and if suppliers can meet the requirements of a transaction. The value chains framework posits five types: Market, Modular, Relational, Captive, and Hierarchy, which increase in complexity across types (Gereffi et al. 2005). This literature is predominantly concerned with international production, although some attempts have been made to integrate finance and tax (Milberg 2008; Dörry 2016).

The intervention made by work on wealth chains is to highlight that contemporary capitalism includes not only processes to create value but also to store and protect wealth. While value-driven processes may benefit from the lowering of information asymmetries, wealth-driven processes are often supported by professional action that seeks to obscure information. So while the value chains framework prescribes enhancing transparency to improve information flows, wealth chains rely on maintaining information asymmetries (Cutler & Lark 2020). Professional action often contributes to these asymmetries in the pursuit of wealth protection, including avoiding regulatory scrutiny. Seabrooke and Wigan (2017) specify five types of wealth chains that deliberately mirror those in the value chains literature to highlight the distinction between production systems aimed at information transparency and financial systems based on opacity and secrecy. The five types are:

- Market chains are arm's-length relationships with low complexity in established legal regimes. Products can be accessed from multiple professional suppliers who compete on price and capacity.

- Modular wealth chains offer bespoke services within well-established financial and legal environments that restrict client flexibility. Products are exchanged with little explicit professional coordination.

- Relational wealth chains involve the exchange of complex tacit information, requiring high levels of explicit coordination between clients and professionals. Strong trust relationships managed by prestige and status interactions make switching costs high.

- Captive wealth chains occur when lead professional service providers dominate smaller ones by dominating the legal apparatus and financial technology. Clients' options are limited by the scope of what professionals will provide.

- Hierarchy wealth chains are vertically integrated. A high degree of control is exercised by senior management and in-house professionals, who coordinate very complex transactions. (Adapted from Seabrooke & Wigan 2017, pp. 10–11)

These types of wealth chains provide different opportunities for professionals to exploit information asymmetries. Recent cases of wealth chains have shown how professionals act to use legal loopholes to protect personal trusts and housing investments (Sharman 2017; McKenzie & Atkinson 2020), enable corporate tax avoidance (Finér & Ylönen 2017; Morgan 2020), offer schemes for tax minimization (Helgadóttir 2021), provide legal advice as a barrier to financial probity (Quentin 2021), and coordinate lobbying in transnational policy fora to protect corporate reputational capital (Christensen 2021). Underpinning this work is the Veblenian view that professional activity to provide “suitable legal decisions bearing on the inviolability of vested interests and intangible assets” underpins a great deal of wealth protection (Veblen 1919, p. 60). The autonomy given to professionals is a source of financial innovation and wealth protection (Gammon & Wigan 2015).

3 Professional action in global wealth chains

To differentiate what types of professional action is common on different dimensions of the transnational economic and legal order, we develop an understanding that marries the Global Wealth Chains approach with work on how professionals mobilize and expand their claims to control within social ecologies (Halliday 1987; Abbott 1988; Liu & Halliday 2019). Research in this domain, focused on professionals in the transnational economic and legal order, stresses how professionals are able to exploit information gaps across ecologies and reconfigure professional practices (Fourcade 2006; Harrington 2012; Seabrooke 2014; Block-Lieb & Halliday 2017).

We can distinguish forms of professional action in wealth chains as incidental and strategic (Quack 2007). First, professionals provide everyday service delivery as users of wealth chains, working with clients and regulators under prevailing norms and rules within the professional community. A key element of professional action here lies in utilizing the “intermediate” role professionals occupy between client and regulatory context by (over)extending professional norms. Professional problem-solving may generate incidental “byproducts” that have emergent political effects. For instance, corporate service providers might sell shell company structures to clients that degrade trust in financial markets (Findley et al. 2013), or lawyers might provide interpretative guidance on tax legislation to deliberately increase indeterminacy in the tax system (Picciotto 2015; Quentin 2021). Here, financial and accounting regulators may also be complicit or independently engaged in enabling information asymmetries, such as when the everyday work of corporate regulators develops a culture of over-confidence distant from traditional professional standards (Gabbioneta et al. 2013). Similarly, the normalization of revolving doors-type careers may encourage undue close communication between regulators and professionals providing services and protecting clients (Adolph 2013; Seabrooke & Tsingou 2020). An additional dynamic of professional action here is when suppliers/advisors come to favor clients' commercial interests in their views of professionalism, that is, what is accepted professional practice over the public interest and established professional norms (Dinovitzer et al. 2014; Field 2017). The ethical boundaries on what is acceptable can be stretched from precaution to readily permissible (Morgan 2011). The normalization of professional practices to exploit gaps can be considered as a form of jurisdictional reconfiguration (Abbott 1988).

Second, on the strategic side of action, a central mechanism for professional action to exploit information gaps is lobbying for new (or the maintenance of established) financial and legal opportunities. Here, professionals work deliberately to create loopholes or to normalize aggressive strategies in pursuit of wealth creation and protection (Seabrooke & Wigan 2017; Christensen 2021). For instance, the financial law-making machineries of small island states have historically been captured by elite foreign lawyers for the benefit of their own service offerings (Palan et al. 2013). More recently, elite practitioners have been centrally involved in the weakening of traction for international financial and tax regulatory initiatives (Baker 2010; Christensen 2020). Policymaking professionals may also reshape professional behavior in wealth chains, such as when international bureaucrats undermine politically and publicly salient legislative initiatives for transparency to seek organizational and professional advancement (Eccleston & Woodward 2014). Another avenue for strategic action is explicit jurisdictional expansion. Professionals can expand the range of wealth creation and protection products available to clients. For instance, the significant expansion of shadow banking in the 2000s, which contributed to and exacerbated the global financial crisis, was driven by professional service innovation to re-tool credit risk for markets, bypassing the established territory of conventional bankers and banking regulation, entering into what was deliberately constructed as a regulatory grey zone (Wigan 2009, 2010; Rixen 2013; Helgadóttir 2016).

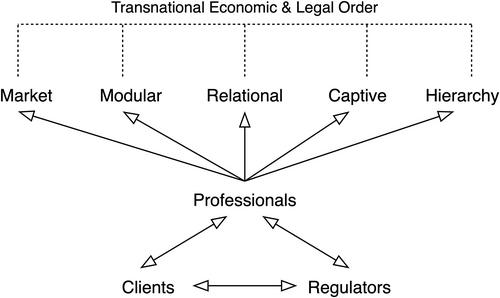

To conceptualize the links between professional action and wealth chains, Figure 1 illustrates the connective logic between micro-level relationships between clients, professionals, and regulators, and the development of profiles that support the different ideal types of wealth chains. At the bottom of the illustration we have relationships between clients, professionals, and regulators. These three parties share (and withhold) information, have sanctioning capacities (legal and financial), and send signals to each other on their status positions and identities. Professionals are often the intermediary between clients and regulators, but clients are also accountable to regulators or seek to influence how they govern. At a localized level the relations between the parties can be understood as establishing what John Levi Martin called “action profiles.” Relationships between the three parties can be located by whether the action profiles produce symmetry (from a reciprocal understanding of how parties should behave), asymmetry (reciprocation is a choice), or antisymmetry (parties have different goals within the relationship, such that one dominates the other) (Martin 2009, p. 21). These relationships are dyadic (client ↔ professional, professional ↔ regulator, regulator ↔ client), where action profiles are formed. The transitive triadic relationship between the client, professional, and regulator establishes a cumulative profile in which regularities about practices and behavior among the parties are made clear and permit market operations (Martin 2011). Variations within the triadic relationship support different ways of organizing. As such, from the cumulative profile there is a link to macro outcomes in supporting a particular type of wealth chain, or combinations of them, that match with the profile and regularize the relations between the three parties.

The development of action profiles between clients, professionals, and regulators occurs under conditions of uncertainty. This uncertainty includes not only the capacity of other parties to do as they intend, but also self-perceptions of capacity (Podolny 2001). It also includes different forms of uncertainty, including over how to manage social relations and parties fulfilling their roles, how to read the meaning of signals between parties, and the possibility of unexpected events (White et al. 2013). Such persistent uncertainty encourages the parties to stabilize their action profiles by affirming particular identities (as types of clients, professionals, regulators) (White 2008). Clients may be risk-averse or risk-friendly on tax avoidance. Professionals may be compliant with rules and ethical codes or stretch both to their limits. Regulators may enforce according to the spirit and letter of the law or be permissive in their treatment of those being governed (Thiemann & Lepoutre 2017). These variations emerge from the maintenance of action profiles and identities.

When scaled up-these relationships between client, professionals, and regulators can function as relations between parties rather than interpersonal relationships. Identity signals and market mechanisms provide shortcuts to all parties in establishing action profiles. Transitivity between parties is difficult to maintain without more trusted and/or secret ways of operating, especially when more complex transactions are involved. Relations between parties are affirmed through repeated actions in the selection of the arrangements and contracts in multi-jurisdictional environments described above as wealth chains. This selection is made by professionals, located in the middle of Figure 1, who are selecting different types of wealth chains. They maintain them through information relationships with clients and with regulators. Clients are selective in what information they will give to professionals and regulators. Regulators try to monitor and understand what clients and professionals are doing. The political, economic, and social positions of many of these professionals recursively reinforce what is possible within the transnational economic and legal order, including the financial and legal possibilities offered through wealth chains (Halliday & Carruthers 2009; Tsingou 2015; Botzem et al. 2017).

Identifying symmetry and antisymmetry in relations between clients, professionals, and regulators is a task for qualitative in-depth cases (Harrington 2016; Thiemann 2018; Beunza 2019; Neely 2021). However, we can propose a series of asymmetries between these parties, where information is not reciprocated or obscured, based on known cases.

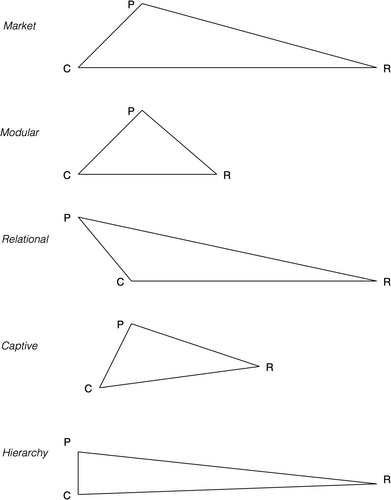

Figure 2 illustrates information asymmetries between clients (C), professionals (P), and regulators (R) across the five types of wealth chains. The distances between each party, marked by lines, represents the level of information asymmetry between those parties. The longer the line, the greater the information asymmetry. The distance between the parties is a function of the relationships between the parties, which is often encoded in the contractual structure of the wealth chain and the financial and legal technologies used.

Source: Authors, based on Seabrooke & Wigan 2017 (p. 14).

In all cases the wealth chain is an articulation of relations between the triad of clients, professionals, and regulators, and the selection and mix of types is a reflection of action profiles within the dyads. The information asymmetries are an outcome of these relations that provide both the incentives and means for those professionals to exploit gaps in norms and regulations. This framework helps us link micro-level professional actions to macro-level structures, including the development of propositions for how regulatory initiatives will unfold, and when market structures may become unstable, based on the client-professional-regulator interactions.

Some chains are characterized by impersonality, where information on clients is absent. In Market chains the Professional is closer to the Regulator than the Client, as the Professional uses international law to hide the identity of the Client, as is common in “offshore” shell companies (Findley et al. 2013). Here, effective regulatory intervention rests on ensuring the availability of information to regulators through registration and verification, with primary examples in “Know Your Customer” type governance schemes and beneficial ownership registration. Such initiatives may challenge the client-regulator asymmetry but may have limited impact due to “mock compliance” (Woodward 2016) or competitive innovation among offshore jurisdictions to develop new secrecy products outside the scope of new regulation. True destabilization of Market chains may thus require robust global information systems with effective exchange of information, exemplified by the powerful Common Reporting Standard developed for financial accounts (Ahrens & Bothner 2020).

In Relational chains often the opposite is the case, with more information on the Client available to Regulators, but not on their assets protected by Professionals. Such Professionals can use legal structures permitted by the uneven regulation of international tax law to hide the Clients' wealth, permitting the Client to be known by Regulators with little consequence, as has been documented with asset protection trusts in the Cook Islands (Sharman 2010). Naming and shaming, or blacklisting with threats of sanctions, through coercive international politics has historically been the main route for attempts at increasing regulatory traction over these wealth chains. But effective interventions have been constrained by the Westphalian nature of the international legal system and strong norms of sovereignty-preservation and lack of coordination that limit regulatory traction (Sharman 2006; Christensen & Hearson 2019).

Other wealth chains are characterized by regulatory permissiveness (Thiemann & Lepoutre 2017). In Modular wealth chains the information asymmetries are short and activities are reasonably well known but permissible according to international law. In cases, such as expat banking in Jersey, political will – and its absence – is critical to allowing (or not) Regulators to properly intervene (Hampton & Christensen 1999). Absent strong international cooperation for deep regulatory scrutiny or wholesale cultural change, many Modular chains are robust against regulatory intervention.

Similarly, in Captive wealth chains information asymmetries are not especially pronounced but professionals have greater control than regulators over financial and legal technologies (Jones et al. 2018; Leaver et al. 2020). Recent years have seen an array of regulatory attempts to expand tax, financial, and accounting documentation requirements for businesses, and to enhance documentation quality and trustworthiness. However, technical mismatches and established norms that leave significant expert power and discretion in the hands of professionals have remained largely unaddressed, meaning that regulators continue to be reluctant to genuinely destabilize Captive chains through radical simplification (and commodification) of skilled professionals' wealth chain services.

Finally, explicit collusion can be seen in Hierarchy wealth chains, where there is close and highly complex coordination between the Client and Professional, leaving Regulators with little information, unless properly resourced and investigated (as with Apple's wealth chain, see Bryan et al. 2017). Many Hierarchy chains are subject to “standard” regulatory scrutiny, such as documentation and audits under general control systems. While these provide Regulators with some insight, mismatches in financial and expert resources, as well as withheld information provides Clients and Professionals with advantages to exploit. Given the core information asymmetries enabled by the close Client-Professional relation, tax and financial Regulators would need to be significantly empowered to offer groundbreaking interventions.

4 Mapping professional action in global wealth chains

To flesh out the theoretical reasoning that links micro-level professional actions with clients and regulators to macro-level outcomes in the form of wealth chains, we provide three case vignettes. We highlight professional action in three types of wealth chains (Captive, Relational, and Modular), focusing on the intermediate forms of transactional complexity where professional action can be identified (as opposed to pure market transactions or complex in-house management in Hierarchy types). These intermediate cases are important for understanding professional action given that discretion is maximized in what information professionals will provide or withhold in their relations with both clients and regulators.

4.1 Professional action on transfer pricing

In the Captive wealth chains of transfer pricing, skilled professionals from dominant suppliers – global professional services firms, especially the “Big Four” (Deloitte, Ernst & Young, KPMG, and PriceWaterhouseCoopers) – engage in both incidental and strategic professional practices to exploit wealth chain information gaps. Transfer pricing is the practice of pricing transactions between related corporate entities – for instance, between subsidiaries within a multinational group (Wittendorff 2010). Over the past century, transfer pricing has grown from a minor technical inconvenience to being at the heart of the modern MNC and of global corporate tax practice: upwards of a third of global trade today is now conducted not between unrelated parties on an open market but between related parties, “inside” MNCs (Lakatos & Ohnsorge 2017).

The transfer pricing choices made by professionals have a large economic scope, and important socio-economic implications. As a consequence, the international community has, since the early-20th century, developed increasingly complex rules to regulate transfer pricing practices. These rules, enshrined in the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines – and used as a template for international and domestic law in more than 100 countries – mandate that intra-group trades should accord with terms available for similar trades on the open market, being “at arm's length.” Five specific methods have been developed to ascertain arm's length compliance: three “traditional” methods using a comparable uncontrolled price, a cost plus, and a resale price basis, and two “transactional” ones based on a transactional net margin method and a profit split method. Each method is applicable in certain situations, depending on the business context, availability of information on comparable transactions, and other factors. Yet all share a fundamental element of flexibility and judgment, arising from the fact that MNCs are treated as a collection of separate entities, networks of independent units rather than unitary groups, with transactions between units under common ownership needing to be priced, enabling corporations to structure and shift their affairs in a tax-aggressive manner (Morgan 2016; Picciotto 2018).

Transfer pricing is marked by perpetual uncertainty and contention over judgments of what constitutes a “similar trade,” the value-added and remuneration due to different activities, and the adjustments required to price at a market-comparable situation. In recent years, regulators are requiring increasingly extensive reporting from clients (advised by professionals) to document transfer pricing practices and systems (Christensen 2021). Fundamentally, however, transfer pricing judgments leave discretion in the hands of individual transfer pricing professionals. Given the transaction to price, professionals will often come to different conclusions (Chang et al. 2008), leading to suspicions that analyses can “achieve any result that the customer may want” and the conclusion that “there is no such thing as an arm's length price” (Rybnik 2010). There is no one “correct price”; instead transfer pricing is to a significant extent about negotiation and the narrative authority of different price analyses (Hussein et al. 2017). Such narratives are tied to professional identity claims of competence and technical superiority, advantaging professionals in the Big Four. As Radcliffe and colleagues note, the “[d]ecisions about what is a “right amount” of tax to pay or what is “acceptable” in the context of public opinion cannot be made without recourse to the highly specialized knowledge base and shared meaning system” (Radcliffe et al. 2018, p. 9).

The implications for wealth creation and protection of transfer pricing practices are substantial: transfer pricing choices have significant implications for the allocation of profits and thus taxable income between corporate subsidiaries and between countries. Suppose a company headquartered in low-tax country X manufactures and sells a unique widget, produced using raw materials from its subsidiary in high-tax country Y. Headquarters have developed a patented design, for which its subsidiary pays royalties to use. Under the “arm's length principle,” royalties paid by the subsidiary and prices for raw materials paid by headquarters should be similar to what independent businesses would pay. Yet the company has strong incentives to over-price royalties and under-price raw materials, so as to shift profits to low-tax country X and not to high-tax country Y. This is especially possible where uncertainty and flexibility is prevalent in the context of intangible assets and other hard-to-value transactions (Bryan et al. 2016).

These opportunities for exploitation have been heavily criticized by regulators in recent years, as the mis-allocation of corporate profits for tax purposes is estimated to account for annual global tax revenue losses of at least $200 billion (OECD 2015). Sikka and Willmott (2010) conclude that transfer pricing contributes to “relative social impoverishment, by avoiding the payment of public taxes” (p. 1) and Ylönen and Teivainen (2018) assert that it represents the political dominance of corporations. Activists identify transfer pricing as a key mechanism behind billions lost for economic development worldwide and as a source of inequality and poverty (e.g. ChristianAid 2008; PWYP 2012).

Very few MNCs, nor tax authorities, have significant in-house expertise in transfer pricing. Instead, the highest concentration of transfer pricing expertise and authority is in the advisory sector, dominated by the Big Four, who have extensive control over financial and legal technologies and knowledge of transfer pricing (Christensen 2018, 2020; Boussebaa & Faulconbridge 2019). Transfer pricing professionals operate as intermediaries between their MNC clients and provide financial reasoning within the established international legal framework to justify their practices to regulators. The practice is that at “virtually every step in a typical transfer pricing analysis, rather than applying mechanical rules, [professionals] need to exercise independent judgment regarding factors that may materially affect the outcome of the transfer pricing analysis” (Andrus & Collier 2017, p. 47). This incidental discretion and flexibility places significant privilege in the hands of transfer pricing professionals in presenting information to governing regulators about what taxes should be paid and where.

Importantly, this engrained flexibility and privilege is embedded – and continually re-embedded – in the professional field, and internalized by regulators. This constrains regulatory traction: without a radical simplification of transfer pricing conventional regulatory interventions have limited systemic impact. The pre-eminent text governing transfer pricing practice states that transfer pricing is not an exact science (OECD 2017), and it is more often articulated as an “art,” which is open to interpretation. This notion is continually reproduced and reasserted by transfer pricing professionals, fending off attempts to reformulate the key standards and codes governing transfer pricing practice (Oats & Rogers 2019). In the face of criticism for the potential social damages caused by transfer pricing practice, professionals have reacted strategically by reshaping wealth chains to mitigate uncertainty by exacerbating power asymmetries. Advisors are increasingly positioning transfer pricing as being part of a comprehensive corporate strategy, rather than a disparate professional practice, further concentrating the power transfer pricing professionals have over financial and legal technologies to maintain their clients in a captive relationship while keepingregulators at bay.

4.2 Professional action on dividend fraud

A case of professional action in Relational wealth chains can be found in dividend withholding tax rebate arbitrage and a transnationally orchestrated professional practice of exploiting asymmetries between sovereign jurisdiction and sectoral regulation. Harnessing fiscal and financial expertise, the “Cum-Ex” scandal generated tax losses of more than €50 billion across Europe for over more than a decade (National Tax Review 2019). While dividend tax rebates can increase efficiency and investment, professional action can exploit legal structures and information gaps between national authorities and regulatory agencies to create markets in grey areas. In the Cum-Ex wealth chain, law, tax, and financial professionals harnessed formal rules provided to establish a transnational tax extraction market.

The professional practice of tax extraction is the appropriation of fiscal resources using tax and contiguous laws in ways that both transgress the spirit of the law, and ways that break the law. In the Cum-Ex schemes, skilled professionals acted strategically to exploit uncertainty embedded in the law to market an adaptable transactional template. The success of the strategy relied upon building ties between professionals and across legal jurisdictions in a manner obscure to regulators. The wealth chain is relational because it relies on a professional network where the transactions are not overly complicated, often known to (some) regulators, but trust and confidentiality among professionals is key for protecting client assets. The Cum-Ex scheme was exposed as systemic fraud once transactions accelerated due to professionals propagating it through the financial system, breaking trust and exposing the practice.

In dividend fraud one basic transaction exploits the lending of shares (temporary sale with an agreement to buy back and return), double-tax agreements, and the shifting of share ownership across borders. The relationship between the client, a foreign equity owner, and the professional is built on the exploitation of arbitrage opportunities. A foreign equity owner may not be entitled to a rebate unless located in a jurisdiction with a double tax agreement with the country of the share issuer that provides this. But the foreign owner can lend shares to a domestic company entitled to a rebate. It lends shares to a company in a country with a double tax agreement just before the dividend payout day. The proceeds of the rebate are split between the original owner and the borrower. Ownership is nominally known to regulators, but professional action generates information asymmetries and the fraud opportunity.

Cum-Ex transactions can also extract two or more rebates, where only one is due, exploiting ambiguity in ownership within narrow time windows around the dividend date. In one transaction, the share owner sells to a buyer immediately before the dividend date. The sale is made with a commitment that the buyer receives the dividend. The sale is not settled on the sales day and the seller remains the legal and beneficial owner, receiving the (actual) dividend from the issuer and the admissible tax rebate from the regulator, the tax authorities. The buyer, on the other hand, receives a dividend compensation (also called a “manufactured dividend”). The compensation is set at the same amount as the dividend. The buyer's custodian bank is, in theory, not positioned to assess whether the dividend received is actual or manufactured. A repeated execution of rapid sales on the dividend date is referred to in the professional community as “looping” (Bundestag 2017).

Fastrup and Svaneborg (2019, pp. 224–227) describe a Danish version of Cum-Ex where US pension funds were established with the sole purpose of executing the transactions. The funds held Danish shares deposited in accounts in a German bank, where shares were traded between the accounts around dividend day. For each trade, the bank's internal system created a credit advice and additional claim to ownership. A separate firm processed the claim and forwarded tax vouchers to the US pension funds. The US pension funds used Barclays in London as a reclaim agent. Barclays requested rebates from the Danish authorities on behalf of the US pension funds. The tax rebates received were sent to the hedge fund Solo Capital. Solo Capital then transferred a proportion of the tax rebates back to the US pension funds and made a deposit in Bank Varengold in Germany.

The German tax lawyer, Hanno Berger is reported to have created the Cum-Ex “master plan.” Berger began his career at the financial supervisory authority in Hessen, Germany, where he worked as a tax inspector with responsibility for the banking sector (Fastrup & Svaneborg 2019). By the end of his career within the financial supervisory authority he held one of the highest-ranking positions within the field of bank tax supervision. In 1996 he moved into private law. When requested to provide a legal opinion to the Australian Macquarie Bank on the admissibility of the trades in Germany, Berger is reported to have instigated a London meeting of law and finance professionals to work on execution. This group went on to widely market the schemes (Mattusek 2019). Berger's career trajectory places him at the intersection between finance and tax as a broker able to synthesize knowledge between professional ecologies and bring together a diverse range of expertise necessary to the trades.

The organizational ecology implicated in the Cum-Ex transactions includes custodian banks, investment banks, insurance companies, pension funds, law firms, reclaim agents, brokers, and hedge funds. Among them, lawyers, financiers, reclaim agents, and brokers were able to form a professional group for dividend fraud. A “master” structure requires adaptation to a variety of national regulations. Professionals like Berger are able to exploit information gaps between regulatory mandates and agencies and locate an opportunity to create a wealth chain (Schick 2018). In this case, while the professional group formed was able to stay small in number and maintain strict confidentiality, the scheme remained under the radar of regulators as incidental professional work. Once relations proliferated and the extraction market expanded the scheme was exposed as explicit strategic manipulation, attracting massive public and political attention that enabled internationally-coordinated regulatory intervention to shut down Cum-Ex opportunities.

4.3 Professional action in ABSs

A case of professional action in Modular wealth chains can be found in the growth of ABSs to the super-rich. Such private services offer a menu of options to an expanding market of wealthy individuals, especially wealth management through offshore services for HNWIs. While ABSs encompass a broad range of consulting services, the sector plays a central role in enabling and exploiting wealth chains by combining financial, legal, accountancy, and other brokerage services, mediating between onshore and offshore markets (Harrington 2016; Santos 2021). In performing professional exploitation functions, offshore ABS providers use forms of professional practice, standards, and codes to help wealthy individuals to escape national regulations, in particular on tax, creating a market with upwards of $8 trillion in assets under management (Beaverstock & Hall 2016).

Professionals in these Modular wealth chains are highly skilled, with a broad range of expertise, enabling them to broker across national jurisdictions to safeguard client wealth and privacy (Francis 2020). For instance, a key reason for the rapid expansion of Singapore's ABS sector was its cross-cutting professional knowledge base and global outlook, allowing the professionals involved to mobilize and capture a substantial, novel transnational market targeted at the super-rich (Beaverstock & Hall 2016). Singapore's history and location as a hub for “expats” and tightly controlled market freedoms have fostered this market.

Professional socialization has been crucial for the development of ABS and cultivated by professionals to homogenize the production of ABSs into a range of services that can be provided to a range of wealthy clients (thus why this is a Modular rather than Relational wealth chain). As Pain writes in her study of ABS ties between London and Frankfurt, what “may appear to be objectively organized strategies are in reality the outcomes of an optimization of social practice” (Pain 2008, p. 10). Professional training commonly takes place in Chicago and London to provide a common understanding of what practices are preferred and how multi-jurisdictional opportunities for wealth management can be located (Jones 2005; Pain 2008). Expatriate professionals are often especially important for the transnational knowledge management of legal practices in a range of jurisdictions (Beaverstock 2004).

Private banking services have typically been the ABS backbone, offering wealth services for the super-rich, brokering across global financial centers such as London, Hong Kong, Switzerland, the Cayman Islands, and the British Virgin Islands (Cassis & Cottrell 2009; Beaverstock et al. 2013). Given the normalization of these services professional work is largely incidental, building on established practices created through prior professional jurisdictional expansion. ABS products also include the creation of investment vehicles, the management of stock options for corporate executives, the creation of corporate entities with limited liability for wealth management, and use of securities and derivatives markets (Wójcik 2013). The establishment of personal trusts in secrecy jurisdictions is also a common item on the menu (Harrington 2012). Professionals actively work not only with their current clients but also foster relationships with their offspring and grandchildren to provide continuity to their client base (Santos 2021).

While professionals have a steady relationship with their wealthy clients through a standardized portfolio of services, there has been increased pressure from regulators in recent years from forward steps in global information sharing (Eccleston & Gray 2014; Kalaitzake 2019). Yet real political intervention on the substance of ABSs has not materialized as the wealth chain services are broadly viewed as accepted or legitimate. Regulatory attention has been met with strategic action from professionals to safeguard wealth creation and protection, like the establishment of MBA programs on wealth management in established universities to further normalize their professional practices, as is common from professional groups seeking to legitimate their activities (Greenwood et al. 2002; Harrington 2016).

5 Conclusion

This article provides a theoretical framework to link micro-level professional actions with clients and regulators to macro-level wealth chains that operate in multi-jurisdictional financial and legal environments. The theoretical reasoning is premised on a micro-foundations argument that at a localized level relationships between parties can be differentiated according to whether the parties involved aim toward symmetry, asymmetry, or antisymmetry (Martin 2009). Those choices between parties within dyads generate “action profiles” for the relationship. When aggregated into the triadic relationship between clients, professionals, and regulators the consequence is the selection of a wealth chain type. Professionals are tasked with the execution and maintenance of these selections, choosing wealth chains based on information asymmetries present within the triad, and then based on transactional complexity and the enrolment of other professionals into trusted or contracted relations. The affirmation of particular identities provides stability to action profiles when parties encounter uncertainty over social relations, market signals, and unanticipated events (White et al. 2013). Clients take positions on how risky they want to be in relation to their financial and taxation arrangements. Professionals take positions on how far they are willing to stretch ethical and professional codes, as well as the law. Regulators take positions on how much they will enforce compliance with the law or permit permissive behavior (Thiemann & Lepoutre 2017). When scaled up these relationships are better understood as relations in a broader market and social system that affirms and supports the transnational economic and legal order.

As professionals are the ones establishing the technical systems and interpretive communities governing finance and taxation (Porter 2014; Hörnqvist 2015), it is important to understand their sources of action. In this capacity professionals act as a form of regulatory intermediary, providing interpretations of legal, accounting, and financial technologies (Talesh 2015; Tsingou 2018). Understanding how they act across multiple jurisdictions is an important issue for regulation and governance, since the “ability of multinationals to augment their structural power through tax havens is unlikely to disappear anytime soon” (Ruggie 2018, p. 324). Locating the sources of professional action is important to understand the chances for regulatory success in addressing systemic regulatory avoidance and evasion. As noted above, professional action can be understood as incremental and strategic (Quack 2007), and such thinking is useful in distinguishing practices and how professionals interact with other parties. Obtaining insights on the inner workings of these wealth chains and the relations between clients, professionals, and regulators relies on investigative work, interviews (Thiemann 2018), and the kinds of financial and legal documentation that provides information on direct relationships (Tischer et al. 2019).

To illustrate the interplay of professional action with wealth chain structures we provided three case vignettes, which show the usefulness of considering professional action within a micro-level and macro-system level context. In the Captive wealth chain of transfer pricing, dominant professionals from the “Big Four” draw on professional discretion, technical superiority and information control to gain power over regulators and clients in assessing the location of corporate profits and taxes. In the Relational wealth chain of dividend fraud, financial-legal professionals strategically exploit jurisdictional asymmetries to obscure regulatory oversight, generating billions in tax losses. And in the Modular wealth chain of ABSs, professionals normalize and socialize around incidental practices of international legal arbitrage that enrich clients and entrench their offshore services.

Our framework contributes to theoretical discussions on regulation and governance on three counts. First, our theoretical reasoning on the micro-level of interactions contributes to the development of scholarship on who is able to act deftly in multi-level regulatory situations (Verbruggen 2013; Lall 2015). This complements existing accounts that emphasize the regulatory-process level sources of professional action (Wansleben 2021). Our stress on information asymmetries between clients, professionals, and regulators also provides a way to identify suspected gaps between formal policy from regulators and actual professional practice on finance and tax matters. When these relations are placed in a wealth chains context is it possible to identify the premise on which they are structured and provide propositions about how they are maintained (Finér & Ylönen 2017). Our case vignettes point to important variation in professional action according to the information asymmetries present. Important sources of variation include: i. the extent to which international law protects a client and corporate entity information; ii. whether professional practices are conducted under client privilege and legal secrecy; iii. how much particular professionals dominate the relevant legal and financial technologies; iv. the degree to which professionals can complicate and obscure transactions within and outside organizations so that regulators cannot locate them on their radar; and v. brute political will that follows from issue salience and valence. These variations are a product of the dyadic relationships between clients and professionals, clients and regulators, and regulators and professionals that generate action profiles. The cumulative action profiles from triadic relations generate preferences for wealth chain types.

Second, we suggest that correcting professional misconduct and wrongdoing is not merely a problem of coordination or an effect of transactional foundations (Marjosola 2021). Rather, as Riles (2014, pp. 75–76) notes in her work on regulatory arbitrage, while the harmonization of rules is often seen as a solution, it is also a cause as professionals seek to use harmonization to create loopholes and scope for reworking professional practices in their favor. Professionals' action profiles reflect not only opportunity structures but also their relationships and the social environment in which they act. Highlighting forms of professional action through national legal systems and private international governance is necessary to identify how multi-jurisdictional loopholes are created that impose a substantial cost on taxpayers.

Third, our framework helps us conceptualize how regulatory interventions in finance and tax are likely to unfold, including how they can be weakened and circumvented through normative as well as formal legislative dynamics. Tax, in particular, is a regulatory area typically described as marked by “hardness,” with a focus on national regulation and authority (Rixen 2013; Hakelberg & Schaub 2017). We suggest the origins, implementation, and use of such formal regulations also depends on the formal and informal rules and standards governing professional conduct (Radcliffe et al. 2018). This opens up a view of tax and financial regulation as emerging not purely from formal national and international politics but from their interplay with professional practice (Hearson 2018). These insights also help us develop propositions for how and when market structures may become unstable. As our case vignettes illustrate, based on the specific client-professional-regulator relations, effective governance varies depending on the availability of quality information, the political will for targeted legal reforms or simplifications, and the presence of well-resourced authorities with strong expertise. All of these factors change the relations between professionals, clients, and regulators, including the extent to which they are working toward similar or opposing goals, and what information they are willing to reciprocate. Future research can develop further propositions on these variations and the likelihood of regulatory reform given existing relations between clients, professionals, and regulators.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the European Commission Horizon 2020 project “Combating Fiscal Fraud and Empowering Regulators” (#727145-COFFERS). Our thanks to the four anonymous reviewers for providing excellent criticisms and feedback, which, over some rounds, greatly improved the article. We have no conflicts of interest to report.